By: Yehuda Fogel

There is a hassidic story about a disciple who once asked his teacher: ‘Rabbi, do you believe that God created everything for a purpose?’ ‘I do’, the rabbi replied. ‘In that case, rabbi, why did God create atheists?’ The rabbi paused and smiled. ‘God created atheists to remind us never to accept the existence of evil. Sometimes we who have faith have too much faith. We accept the evils of this world as the wills of God. They are not the will of God, which is why God created atheists to cure us of this illusion. – Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, To Heal a Fractured World

Rabbi Nachman of Breslov (Likutei Moharan 19) commented that tsaddikim, the truly righteous, are like mirrors, in that people need only look at their faces to feel the pangs of penitence, without any words of rebuke. In the world of today, we spend our time looking more at faces on Twitter than we do at faces of a tsaddik, or even at our own friends and loved ones. How are we then to learn from the wisdom of our greatest sages? Lucky for us, the great Sufi poet Jalaludin Rumi, who died some 800 years ago, was sensitive to this dilemma. On his gravestone, there is the following epitaph: “When we are dead, seek not our tomb in the earth, but find it in the hearts of men.” We may edit this slightly, and suggest that we seek also in the books of the hearts of men, in the writings and wisdom of those sacred departed.

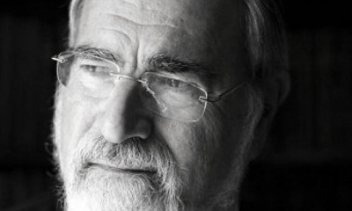

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks was many things to many people: a leader, a lord, a popular scholar, friends with high and low alike, literal kings and queens and simple people. Above all, or perhaps we might say through it all, in it all, he was also a teacher of Torah—a shockingly humble, prescient teacher of a timeless Torah, often in a radically contemporary idiom. His books can speak to anyone, and his teachings mix the particular and the universal with a near-emblematic balance. This great visionary invites us to have ever more faith, in ourselves, in God, in our world, and most of all in the possibility of improvement. Simply put: in responsibility, and with responsibility, we can build better worlds.

As we mark the one-year anniversary of his death, we are seeking his wisdom in the hearts of people, and in the books of the heart, by turning to our favorite words and ideas from Rabbi Sacks’ luminous writings.

1. The ‘Abandoned’ Tsadik

From To Heal a Fractured World, p. 57 – 58. In this passage, we see the ethic of responsibility that Rabbi Sacks championed again and again at its apotheosis, ringing brightly through the texts of the Torah and a moral life.

“I cherished an interpretation Mo Feuerstein offered (he had heard it, I think, from Rabbi Joseph Soleveitchik) of one of the most difficult lines in the Bible: ‘I was young and now am old, yet I have never seen the righteous forsaken or their children begging for bread’ (Ps. 37:25). Edmund Blunden, the First World War Poet, wrote an ironic commentary on it:

I have been young, and now am not too old;

And I have seen the righteous forsaken,

His health, his honour and his quality taken.

This is not what we were formally told.

The verb ‘seen’ [ra’iti] in this verse, said Feuerstein, is to be understood in the same sense as in the book of Esther: ‘How can I bear to see [ra’iti] disaster fall on my people?’ (Esth. 8:6). ‘To see’ here means ‘to stand still and watch’. The verse should thus be translated, ‘I was young and now am old, but I never merely stood still and watched while the righteous was forsaken or his children begged for bread.’ It was a lovely insight, central to the theme of this book.

God does not want us to cease to be human, for if he did, he would not have created us.

Back in Britain I heard little of the Feuersteins until a news-cutting caught my eye. In late 1995, the textile mill the family owned in Lawrence suffered a devastating fire – the worst in Massachusetts for more than a century. By then, most of the textile mills in New England had been closed. There was cheaper labour to be had in Mexico, India, or Asia.

Many assumed that the owner, Aaron Feuerstein, by then 70 years old, would simply take the opportunity to collect the insurance and close the mill. What caught the headlines was his principled decision not to do so. The business was a major employer in the town – 1800 people worked in it – and he felt a strong sense of responsibility to them and their families. He announced, first, that the mill would be rebuilt; second, that for the next 60 days all employees would be paid their full saiaries; third, that their health insurance had already been paid. It would be good to be able to say that virtue was rewarded. In strictly economic terms it was not: the business faced ongoing difficulties. But Aaron Feuerstein kept his word and became known as the mensch of Malden Mills.”

2. Closing Our Eyes to See

From To Heal a Fractured World, p. 22. In this powerful passage, Rabbi Sacks urges us to take a startlingly human stance in building a better world, one in which we turn away from God, with God’s permission, to see the world in its mundane, human pain.

“To be a parent is to be moved by the cry of a child. But if the child is ill and needs medicine, we administer it, making ourselves temporarily deaf to its cry. A surgeon, to do his job competently and well, must to a certain extent desensitize himself to the patient’s fears and pains and regard him, however briefly, as a body rather than as a person. A statesman, to do his best for the country, must weigh long-term consequences and make tough, even brutal decisions: for soldiers to die in war if war is necessary; for people to be thrown out of jobs if economic stringency is needed.

Parents, surgeons, and politicians have human feelings, but the very roles they occupy mean that at times they must override them if they are to do the best for those whom they are responsible. To do the best for others needs a measure of detachment, a silencing of sympathy, an anaesthetizing of compassion, for the road to happiness or health or peace sometimes runs through the landscape of pain and suffering and death.

If we are able to see how evil today leads to good tomorrow – if we were able to see from the point of view of God, creator of all – we would understand justice but at the cost of ceasing to be human. We would accept all, vindicate all, and become deaf to the cries of those in pain. God does not want us to cease to be human, for if he did, he would not have created us. We are not God. We will never see things from his perspective. The attempt to do so is an abdication of the human situation.

My teacher, Rabbi Nahum Rabinovitch, taught me that this is how to understand the moment when Moses first encountered God at the burning bush. ‘Moses hid his face because he was afraid to look at God’ (ex. 3:6). Why was he afraid?

Because if he were fully to understand God he would have no choice but to be reconciled to the slavery and oppression of the world. From the vantage point of eternity, he would see that the bad is a necessary stage on the journey to the good.

He would understand God but he would cease to be Moses, the fighter against injustice who intervened whenever he saw wrong being done. ‘He was afraid’ that seeing heaven would desensitize him to earth, that coming close to infinity would mean losing his humanity. That is why God chose Moses, and why he taught Abraham to pray.”

3. Non-Dualistic Chosenness

Unlike the previous two texts, this text is really an entire book: Rabbi Sacks’ epic, Not in God’s Name: Confronting Religious Violence. For a book that tackles religious violence in the broadest terms, in varying faith traditions and locales, this work is stunningly specific in its claims about the biblical texts at the heart of much debate, and Rabbi Sacks makes powerful claims about what he refers to as counternarratives in the text. While we might think of the book of Bereishis as one in which we are urged to choose between differing options, between dualistic oppositions of good/bad, of Yishmael/Yitzchak, or Yaakov/Esav, Rabbi Sacks reads in the text a counternarrative of compassionate equivalence, one that sees the unchosen as a part of the very same story. For more of this, you really have to read the book, so we will give you just a taste of what it has to offer, and the wisdom that flows through this work. The following is from Not in God’s Name, p. 81. This is a tease. We repeat: This is a tease. We are OK with that. Get the book, and then you too can tease others with this.

“What if the Hebrew Bible understood, as did Freud and Girard, as did Greek and Roman myth, that sibling rivalry is the most primal form of violence? And what if, rather than endorsing it, it set out to undermine it, subvert it, challenge it, and eventually replace it with another, quite different way of understanding our relationship with God and with the human Other?

What if Genesis is a more profound, multi-leveled, transformative text than we have taken it to be? What if it turned out to be God’s way of saying to us what he said to Cain: that violence in a sacred cause is not holy but an act of desecration? What if God were saying: Not in My Name? Such a suggestion sounds absurd.

Jews, Christians and Muslims have been reading these stories for centuries. Is it conceivable that they do not mean what they have always been taken to mean? Yet perhaps this is not as absurd as it sounds, because until now each tradition has been reading them from its own perspective. But the twenty-first century is summoning us to a new reading by asking us to take seriously not only our own perspective but also that of the others. The world has changed. Relationships have gone global. Our destinies are interlinked. Christianity and Islam no longer rule over empires. The existence of the State of Israel means Jews are no longer homeless as they were in the age of the myth of the Wandering Jew.

For the first time in history we can relate to one another as dignified equals. Now therefore is a time to listen, in the attentive silence of the troubled soul, to hear in the word of God for all time, the word of God for our time.”