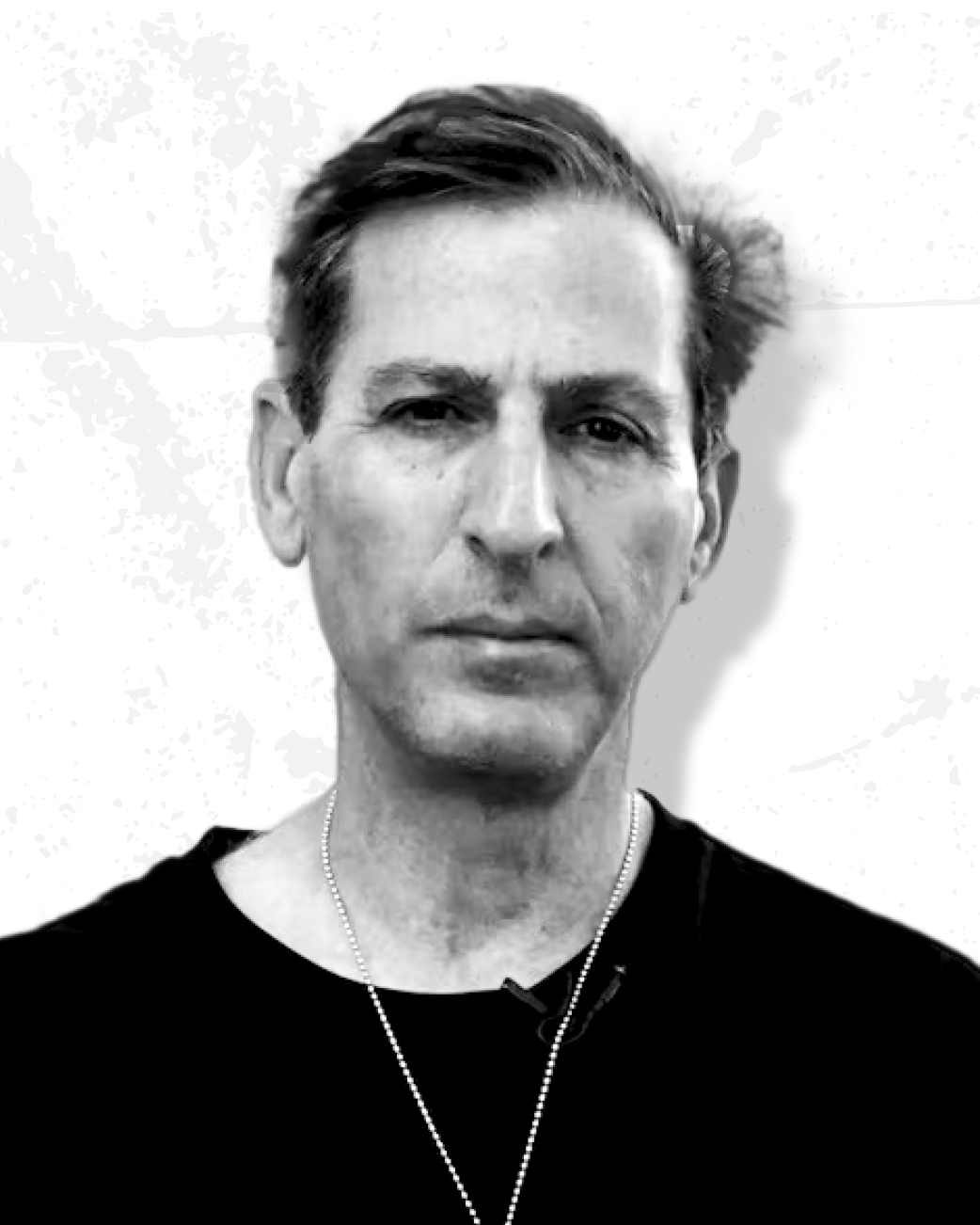

Rabbi Meir Triebitz: How Should We Approach the Science of the Torah?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rabbi Meir Triebitz – Rosh Yeshiva, PhD, and expert on matters of science and the Torah – to discuss what kind of science we can learn from the Torah.

Summary

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rabbi Meir Triebitz – Rosh Yeshiva, PhD, and expert on matters of science and the Torah – to discuss what kind of science we can learn from the Torah.

The Torah, and especially the Talmud, addresses a wide subject matter including theology, morality, metaphysics, and science. It is sometimes said to contain all knowledge – meaning that we could learn anything from the Torah, which seems to imply that all of the Torah’s scientific claims are true. Some welcome this perspective, while others object to it.

- What is the Torah’s subject matter?

- Does it contain irreconcilable scientific claims?

- Should a statement’s subject matter change how we interpret it?

- What if we aren’t supposed to interpret a statement as scientifically true, but our Halakhah today is in some way predicated on the statement being true?

- And does our not interpreting a statement literally mean it isn’t true, or just that we can’t understand it?

Tune in to hear Rabbi Meir Triebitz discuss his perspective on these age-old science and Torah questions.

Transcript

David Bashevkin:

Hello, and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast, where each month we explore a different topic balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host, David Bashevkin, and this month we’re exploring science and religion. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big, juicy, controversial topics that come up when Jewish life, religious life, bumps up into the modern world. So be sure to check out 18Forty.org – that’s 1-8-F-O-R-T-Y.org – where you can find videos, articles, and recommended readings.

So a question I get a lot is, “How do you choose your guests? How do you choose who to talk about a specific subject?” And I think, as opposed to many other podcasts, we actually have an easier time choosing our guests, because our podcast isn’t just about interesting people, or dare I say meaningful people, or smart people, or funny people. We try to… Each month we pick a topic, and we want to do a deep dive in this topic and have different people from different angles be able to talk about it. So right away, there’s a very easy system that, we have a topic at hand that we need to find people to speak about it.

But once you have your topic, whether it’s comedy, or Talmud, or Jewish peoplehood, then it gets tricky. How do you find the experts on any one of these given topics? And the reason why I’m introducing our guest today with this question is because I definitely hesitated to have Rabbi Dr. Meir Triebitz on. I pursued him for a very, very long time. He’s not as well-known as some of our other guests in America, but he has an incredibly fascinating take, and this gets into how I choose my guests. I think sometimes you choose a guest because their approach, their clarity, the way that they give things over is so clear, so moving, maybe it’s their personal story, that you know that they’re going to shed light and a perspective on the topic at hand that nobody else could do.

I don’t think that’s what was at the front of my mind with Rabbi Dr. Meir Triebitz, I think there was something else with Rabbi Triebitz. And that is, I think that there is a value sometimes in just knowing that certain people are out there, and Rabbi Triebitz is one of those people. I’m going to be honest right from the get-go, and that is that Rabbi Triebitz’s style and speaking, it’s fairly complex. He gets all the way in deep on a certain subject, and his thought is iterative and a little bit hard to follow at times. That’s no, God forbid, criticism on Rabbi Triebitz, he’s not a professional podcaster, he’s a Rosh Yeshiva, teacher, and educator, and I’ll tell you more about him in a second. But I think his mastery, and almost his willingness to ask and confront some of the most radical questions related to religion, Torah, Judaism, and the modern world, knowing that a mind and a person like that is out there, I think, in and of itself, serves a very important purpose of sorts.

There are a lot of other places where you can find his recordings. They’re not so easy to find, but if you Google Rabbi Meir Triebitz, you’ll find a great deal of stuff on torahdownloads.com, on toseftaonline. He has a lot of really amazing stuff. He doesn’t write a great deal, but the topics that interest him have always fascinated me, and it’s at the heart of why I went after him. I sent a ton of emails, he’s so, so busy, lives in Eretz Yisrael, in Israel, and was a little bit hard to pin down, but he was so gracious and so kind to spend time talking about this.

I think the wow of Rabbi Triebitz is to look at the topics that he confronts, and we’re going to have links to hopefully as many of his writings as possible, but Rabbi Triebitz has always been interested in the canonization of the Talmud. How did the Talmud come together? What is the Talmud itself? And he’s given not one, not two, but dozens, maybe 20, 30, 40, a 40-part series on these big questions, like, “How was the seminal act of bringing together all of Jewish thought, ideas, practice, law, which is the Talmud, in one place, how was that done and what does it represent?” And I think in many ways, understanding the Talmud and what the Talmud’s trying to accomplish is a window to understanding why, very often, the Talmud seems to represent scientific views that do not cohere with modern science. It’s a question on what was being canonized, what was being done, and why was it being done. That’s really at the heart of our conversation.

So whether or not you’re able to follow, or have extra time to look up some of the sources, all of which hopefully we’re going to link to on 18Forty.org, so please check it out, whether or not you’re able to follow, knowing that Rabbi Triebitz is out there, seeing the questions that he is willing to confront is really a purpose in and of itself.

Just a little bit about Rabbi Triebitz. Rabbi Triebitz teaches in a yeshiva known as Machon Shlomo, which is a yeshiva for Ivy League grads who weren’t afforded a Jewish education in the way that many other people go to yeshivas in high school and elementary school. And this is taking people who didn’t get that opportunity, are clearly superbly bright, I’ve always been enamored with the work that Machon Shlomo has done, and Rabbi Triebitz is a rebbe at Machon Shlomo, as well as teaching philosophy, Halakhah, and Chumash. He graduated with an undergraduate degree in physics from Princeton and a PhD from Stanford. So this is someone who has been deeply immersed in both the secular scientific world and the world of Torah, he is an astounding contributor to Torah.

And either one of his contributions in either of these fields could have taken your average man a lifetime. The fact that he has masteries in both of these is a testament to his brilliance. Rabbi Triebitz has also taught for Tikvah, and the hashkafacircle.com. He’s done such amazing work, which is why I’m so excited to share this conversation, but more so to share the personality and who he is. He didn’t want to talk about himself at all. Maybe we’ll have snippets of that in the beginning. He wanted to stick to the questions at hand, he didn’t want to get into his upbringing, and his life, and all that other really fascinating stuff. And maybe we can convince him another time to come back to talk more about that, because there’s so many more questions I could have asked Rabbi Triebitz.

But Rabbi Triebitz, more than even the conversation that we had, which I thought was absolutely remarkable, his idea, his brilliance, and his mastery are something that all of our listeners should be familiar with. He has contributed and elucidated some of the most complex questions related to Jewish thought and modern ideas and how they cohere and adapt with one another. It is my absolute pleasure to introduce my conversation with Rabbi Meir Triebitz.

Welcome everyone to the 18Forty Podcast. It is a distinct privilege and pleasure to welcome Harav Meir Triebitz, who is a Rosh Yeshiva at Yeshivas Machon Shlomo, who teaches many yeshivas in Eretz Yisrael. He is a prolific writer and speaker. He has a PhD from Stanford University in physics, and has an unbelievable story and trajectory of both a deep secular knowledge of understanding science and ideas, and an even richer current responsibilities and job, so to speak, teaching Torah and the uniqueness of Torah to a new generation of Jews. Rabbi Triebitz, it is really an honor, privilege, and pleasure to speak with you today.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

It’s a pleasure to be here with you.

David Bashevkin:

So we’re not going to get into all of the details of your upbringing. Can you at least tell us what was the focus of your studies at Stanford?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

I was interested in mathematics and science, and how should I say it? I was interested in… The focus was really mathematics but theoretical mathematics has applications in science, et cetera, in physics, that was the main focus.

David Bashevkin:

Okay, so I want to jump right in, and I want to begin with an extraordinarily famous Mishna in Pirkei Avos. The Mishna in Pirkei Avos says, “hafech ba v’hafech ba d’kula ba, turn it over and turn it over, it is all there,” referring to the wisdom contained in the Torah, and as we explore the idea of science in Torah, I was wondering if you could begin by explaining, what does that mean? Does that mean all of science, all of contemporary physics and mathematics are contained if you learn enough Chumash, enough Torah, enough Talmud, enough Gemara, you could become a nuclear physicist, you could become a doctor?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

No.

David Bashevkin:

What does that mean that if you turn it over enough it is all there?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Look, in other words, there is a machlokes mefarshim about [inaudible] but I think that anyone who’s going to use the Torah of Chazal, and certainly the Chumash, at arriving in a certain type of scientific discovery I think is mistaken, and actually is very, very dangerous. It is true that the underlying, the Torah, which is min hashamayim, so on the underlying basis, right?

David Bashevkin:

From heaven, I’m sorry if I interlude with some brief translations.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

That’s okay. Right. At the end of Mishpatim, the Torah speaks about that Moshe Rabbeinu came, and to give the Torah to Klal Yisrael, right?

David Bashevkin:

The Jewish people, yes.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

The Jewish people, and the Jewish people had a tremendous vision. A tremendous vision. The Torah describes there a tremendous vision they have, kavayachol of a tremendous metaphysical vision. And then, it says, but Hakadosh Baruch Hu, as not to upset the joy of that day, there were certain people who looked at it b’lev gas, meaning that they were eating and drinking, and they didn’t take it, I guess, with the appropriate seriousness that it required. So Hakadosh Baruch Hu says to Moshe Rabbeinu, “Aley elay hahara” –

David Bashevkin:

Come up on the mountain.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Mountain, right, and I will give you, and the pasuk says ” Es luchos ha’even v’haTorah v’hamitzvah asher kasavti lehorosam”. I will give you the Torah. Now in Gemara on daf hey amud alef, in Brachos, the Gemara there says that what is this pasuk referring to? So the Gemara says that it’s referring to the luchos ha’even, which is the two tablets, it’s referring to the Mishna, it’s referring to Nevi’im and Kesuvim, and it’s referring to the Gemara.

David Bashevkin:

It’s all there.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

However, what’s interesting is, what happened. In other words, at first they had this incredible metaphysical vision, and after that somehow Chazal tell us that the zekenim, the elder people, somehow they didn’t take the right approach. They looked at it b’lev gas, with a certain arrogance, and therefore Hakadosh Baruch Hu says to Moshe Rabbeinu, I’m going to give you Mishna and Gemara. So you could look at the Meshech Chochma there, he explains the pasuk, “asher kasavti”, so we have to say that there is a Torah of Hakadosh Baruch Hu, and the Torah of Hakadosh Baruch Hu roots the Torah in the truth, in the truth of the physical world. That’s the root of the Torah. But man is not privy to that truth. Man has to learn the Torah, the Mishnah, the Gemara, in other words, in the way in which the Torah should be ba’al peh.

David Bashevkin:

The oral law.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

The oral law, the way with the oral law, we have the oral law as tradition. Which means that, in other words, even though the Gemara says, for example, the Gemara says on kuf amud beis in Eruvin that if the Torah was not given, we can learn ethics from the animals. But nonetheless, so that’s the Meshech Chochma [inaudible], that’s called the Torah shekasavti, that’s Hakadosh Baruch Hu’s Torah. But ultimately, science is a human activity. Science is a human activity. Man is supposed to learn the oral law in terms of the Mesorah, the tradition, that we have from the sages, and man should not think that the Gemara, the sages, are privy to this ultimate scientific truth. Which serves as the basis of the Torah, but this is not man’s road, this is what man does. So in my opinion, there’s science, according to the Torah, science is very much a human activity. The Torah, Chazal, the tradition of Chazal are communicating the d’var Hashem, the tradition of the oral law. Not only oral law, but Chazal was speaking in terms of the science of their day. And this is explained by the Chazon Ish, he speaks about this when he speaks about the laws of treifus, animals which are rendered forbidden to be eaten because they’re missing things which they won’t be able to live very much longer, that Chazal in fact actually decided Halachic issues are based upon their science, and we shouldn’t think that Chazal were privy to all the advances of science that we have today. That’s a very, very important thing.

David Bashevkin:

So if I understand you correctly, there’s this notion that there’s this supernal, transcendent Torah that we don’t necessarily have access to when we open up to interpret the Mishna or the Gemara. And maybe that was the Torah that reflects all of the truths of the world, but the Torah we have in front of us is much more narrow in its focus of what it’s coming to resolve?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Right, right. And that’s why it’s very important. So for example, there’s an interesting, we can go on for a long time about this. If you look in the teshvuva, the response to Reb Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, Reb Shlomo Zalman Auerbach has a give and take, a “massa umatan”, with the Chazoni Ish, and they’re speaking about electricity. The Chazon Ish, as we all know, was of the opinion that if a person puts on an electrical gadget, an electrical item, there’s a prohibition from the Torah which is called binyan, which is called –

David Bashevkin:

On Shabbos.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

On Shabbos, right, speaking about on Shabbos. So Reb Shlomo Zalman says that he doesn’t understand. He says, based upon what the physicists tell us about electricity, that a person puts on the switch and there’s a flow of electrons, so he says, “What’s the difference between putting on a switch on Shabbos, like putting on a fan, and turning on a faucet that the water goes through the faucet?” The Chazon Ish gives a very interesting answer, and he says, “Yeah, but don’t you understand that the instrument is going misa l’chayim, from death to life, it’s like it’s coming alive.”

So what I understand from the massa umatan from Reb Shlomo Zalman as the following thing. It might be that in modern physics, if I ask you to describe electricity, you would speak about the flow of electrons. The question is, if you turned on a fan in front of Ravina and Rav Ashi what would he say? Ravina and Rav Ashi didn’t know quantum physics, Ravina and Rav Ashi would see an incredible thing. You have metal here, and then the metal comes alive. So the Chazon Ish was telling Reb Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, we can’t judge and try to understand Chazal in terms of modern science. If you want to understand the da’as Torah, the legal opinion of Chazal on different issues, we have to place ourselves in the position of Chazal, and what would Chazal say about this thing? That’s what the Chazon Ish was saying to Reb Shlomo Zalman.

David Bashevkin:

Fascinating. We have to superimpose the conceptual world of the Gemara onto modern day phenomena to assess its implications.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

I always claimed that I think that Reb Shlomo Zalman actually agreed to the Chazon Ish eventually. There’s a very interesting, I don’t know if it’s a teshuva, but Reb Shlomo Zalman writes about the elevator. Can a person go in an elevator on Shabbos? Let’s say an elevator’s working by a Shabbos clock, but it’s not what’s called a “Shabbos elevator”, but when the elevator goes down the motor’s working harder. So Reb Shlomo Zalman says, “Wait a minute, why it is permitted?” He goes, “Even though it could possibly be that if you look into the mechanical motion of the motor, the motor is actually exerting much more energy, but I see the elevator going at the same speed.”

In other words, from the human point of view, it doesn’t seem like I’m doing anything to the elevator. If I go into the engineering of the elevator I’m going to see obvious changes. But on the other hand, as far as I can see, the elevator is actually moving at the same speed all the time, and because of that Reb Shlomo Zalman held, I know this actually from someone who spoke to him, that you don’t really need what’s called a Shabbos elevator which regulates the motor, but actually you could have an elevator going on a Shabbos clock, and that’s good enough. It’s very interesting, Reb Shlomo Zalman Auerbach also went just a little bit further, followed this understanding of the Chazon Ish with the refrigerator, opening up a refrigerator. He has a long teshuva on the refrigerator.

David Bashevkin:

On Shabbos. I just don’t want any listeners to think they –

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

I’m sorry, I’m sorry.

David Bashevkin:

Can’t open up the fridge during the week.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

I’m sorry. But then Reb Shlomo Zalman wants to say that a [inaudible] has to be the one opening the refrigerator all these intricate electronics isn’t happening, but that’s not why I’m opening up the refrigerator. I’m opening the refrigerator to get my food. In other words, these things are happening, but they don’t enter into the “lech basheva”, the intentionality, that’s the vital Halachic factor whether opening the refrigerator is prohibited or not prohibited. Therefore we have this same concept. In other words, and this is something, not everybody actually goes like this, but we have seen that when we look at a question, this is the Chazon Ish, when we look at the question, the question is, how would Chazal look at this? Which we could –

David Bashevkin:

Now can you explain, because it’s such a fascinating concept that you’re saying. You’re saying conceptually, when we assess Halachic Jewish legal questions, we’re not trying to get to the root and the lens of science, we’re not even trying to get to a contemporary understanding. We’re trying to superimpose an understanding from nearly over 1,000 years ago. Why –

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Right. So that – yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Why conceptually are we frozen in time when we assess Jewish legal questions?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Yeah, okay. So there’s two reasons. First of all, in traditional Judaism, our authority is Chazal.

David Bashevkin:

Chazal means what?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Chazal, that’s called the Gemara, the Amoraim.

David Bashevkin:

Okay.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

I’m coming to interpret the Chazal, but we’re speaking about the Gemara here. In other words, Judaism understands that Halachic authority ultimately is in Chazal. In the Gemara on lamed gimmel amud aleph in Sanhedrin there’s a machlokes between the Bal Hame’or and the Rush –

David Bashevkin:

A dispute, yeah, between later, yeah-

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

A dispute, but can the rishonim, the medieval commentators, actually argue on the Geonim and go back to the Gemara? And actually, the Rush rules at the end that the final authority is the Gemara. In other words, the final authority is the Gemara. A rishon, a medieval commentary, can argue on let’s call the period of commentators from let’s call it from the sixth century to the tenth century, they’re called the geonim, because you could bring a raya from the Shas. In other words, ultimately the source of authority is the Shas. So if the source of authority is the Shas, we can’t impose knowledge that the Amoraim didn’t have. But rather, in fact the da’as Torah that’s involved in deciding a Halachic issue is, how would Chazal look at this? And that’s the important thing. I think a lot of people miss this bzman of today, but I think that’s really, and that’s why learning Gemara still becomes the paramount and central basis of all Halakhah.

David Bashevkin:

Now could you explain a little bit, I’m going to follow up with some of my own difficulties related to the science that’s characterized in the Gemara. Could you just speak a little bit more, where does that authority derive from? It was sealed, I didn’t sign off on that, why is it that there is this very sharp division between what is written in the Gemara, and even the evolution of the Gemara, it’s so vague when it was actually canonized. Why is that such a seminal break in Jewish history, where does that authority derive from that none of, nobody here, even if you’re a big genius, a very holy person, you can’t dispute what has been canonized in the Gemara?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Okay. Like this.

David Bashevkin:

And I’m sorry to ask such a massive question.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

No, you’re asking, there’s two questions, I think you’re really asking two questions. The first question you asked me is, “Why is the Gemara an authority?”

David Bashevkin:

Yes.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Why is the Gemara an authority. Okay, this is something which is actually discussed, it’s a very famous give and take between the Chazon Ish and between Reb Elchanan Wasserman, Hashem yikum damo. With the massa umatan, why in fact, actually, what made the Gemara special that we can’t argue with the Gemara? Rav Elchanan Wasserman seems to suggest that somehow it was actually…

David Bashevkin:

A consensus, like a unified gathering.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

It was a consensus, right? And the Chazon Ish says something a little bit more abstract, that basically there was an understanding of the yeridas hadoros.

David Bashevkin:

Like metaphysical, like just our connection to God and to law changed.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

I want to say like this. I’m not sure that the Chazon Ish meant like this, but I’m going to claim that this is probably, if you would ask the Chazon Ish and push him, he probably would agree to what I’m saying.

David Bashevkin:

Okay.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

You can’t give a reason why the Gemara was accepted, because if you can give a reason why the Gemara was accepted, it could be violated. In other words, by definition, the establishment of the authority of the canon cannot have a reason. Just like, for example, you can’t give a reason why God created the world, because if you can give a reason why God created the world, then you’re like God. Even though I know from hashkafah, everybody asks why God created the world, but as the Leshem explains and the Arizal, that’s only to be stated from our perspective. When we say God created us for a certain reason, the question is, how should we look at creation? But ultimately, on the God side, I can’t say why God created the world. So I think in much a parallel way, we can’t say, we can’t describe the process by which the Gemara became an authority: it just became an authority.

Now how did it become an authority? It seems to be very, very clear. What happened was, is that a certain period of time, all the Gemara became a text, and everybody started interpreting the text. It was like a process. We don’t know how the process, what gave root to the process, but nonetheless, at a certain point of time, and according to what I say, probably between the eighth and tenth centuries, already we see that the majority, the poskim, those Halachic authorities would rule based upon their understanding of the Gemara. Once the Gemara becomes the canonical text of authority, and that all rulings are really interpretations of the Gemara, then min eyle, in a natural way, the Gemara is established like that and that is its source of authority. In other words, I wanna claim is that in fact you can’t give a reason why the Gemara’s an authority, but it became an authority.

David Bashevkin:

It’s existence, it’s very existence and the way people relate it –

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

It became an authority.

David Bashevkin:

Specifically as as an authority.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

That’s right.

David Bashevkin:

Why was it an authority? You’d have to be… So here’s my question as it relates to that. And I’ve had this, this has troubled me personally for a long time. Very often in the Gemara, you have things that were canonized as a part of the Gemara that are clearly, they don’t seem to have contemporary applications. You have folk wisdom, how to cure an illness, blood-letting, all of these medical issues. And you look at that, and again people talk about it and say, “Oh, they were just giving the medicine of their time, don’t worry about it.” But here’s what frustrates me.

If the Gemara was meant, in fact, to be the canon that guides Jewish practice for centuries, why did they canonize that? Did they not know at the time that this was meant to be, what we talk about in prophetic books in Tanach. We say we canonize prophecies that are ledoros, that are for all generations. So why did we canonize things in the Gemara that seem to be so temporal that, here’s the way to cure your stomach ache, but don’t try this after the eleventh century because you’re going to get ill from it. It shakes my confidence in the very deliberateness of the canonization itself.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Yeah, so I was like this. I don’t think that at one point a person said, “Okay, we’re canonizing this.” The Gemara is what’s called an oral tradition, and just like, for example, I’m speaking to you right now, so we’re speaking about science and Torah, but we might speak about other things too, whatever it is.

David Bashevkin:

I hope so.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

In other words, the Gemara speaks about aggaditas, this and that, aggaditas might have been –

David Bashevkin:

The stories, sure.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Right, in other words, so what happens is there was this oral tradition that was continued for many generations, and at certain point was frozen. It’s not that someone actually decided, “Well, we’re going to create this canon,” because if a person decided to create the canon, you could ask them, “Why’d you create the canon?” It suddenly was frozen. So in other words, these are all traditions that were frozen. Once you freeze an oral tradition, basically you’re freezing all of these oral traditions, and some of the oral traditions are Halachic, but some of them are not Halachic. In other words, this goes back to the point I’m try to make. It wasn’t a intentional, it wasn’t a, how should I say it, a design. It was frozen at a certain point. At a certain point, somehow nothing was added to the Gemara, and all these different things that the Gemara brings, whether aggaditas or maybe medicines, Chazal were interested in medicines too, and this became part of the corpus.

In other words, we’re not speaking about intelligent design. We’re speaking about intelligent design, therefore you have a question: “Why did I intelligently put this in and not the other thing in?” But we’re speaking about something that somehow happened, it was a, how should I say it, it was a tradition that was frozen at a certain point. So what they froze was the discussions not only regarding Halacha but aggadita, but also different types of medicines that Chazal were interested in.

David Bashevkin:

Doesn’t removing the deliberateness of the canonization kind of shake our ability to be so interpretive? Meaning, the way that we approach every other Halachic passage in the Talmud is with such deliberateness. We ask contradictions from here and there, and we approach the overall text as if there was an intelligent design and a deliberateness to it. So what –

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

I’ll tell you, yes and no, yes and no. Let me tell you, for example, when I give a shiur in Machon Shlomo, we learn let’s say Gemara Rashi and Tosfos. So I ask the boys, “Who was the editor of the Shas?” They’ll say, “Ravina, Rav Ashi, [inaudible].” I said, “No, the Tosfos was also an editor of the Shas.” Because what happens is, when there’s a contradiction between two passages in the Gemara, and Tosfos comes in and really creates a teretz, Tosfos is editing the Shas too. In other words, the editing process didn’t really end at a certain point, it continued, except that the further editing would not violate the initial editing, it would add layers on top of it. So in other words, what we have to understand is that the oral law is not something which is static, it continues. Even when Poskim write teshuvas today, Rav Moshe Feinstein writes teshuvas which actually come up with tremendous chiddushim in Halakhah, that’s part also of the editing of the Gemara. In other words, Rav Moshe Feinstein chas v’shalom is not going to argue with the Gemara, but he might come to find different ways of resolving contradiction in the Gemara, which is also a type of editing too.

The purpose of the oral law is very important. The oral law is supposed to evolve. Why is there a written law and an oral law? How come Hakadosh Baruch Hu, God didn’t give us just a written law? The answer is, there’s a part of the law which has to remain fixed, rigid in time, because that’s ultimately the authority, but there has to be a part of the law which allows it to evolve. In other words, the oral law in a certain sense evolves the written law, that’s what it does. “Evolution” is a dirty word for many people, but the truth is that Chazal evolved the written law. The Rambam says in shoresh beis, and it’s the way I understand shoresh beis in the Rambam –

David Bashevkin:

In his work on the commandments.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Right. And that actually, “ein mikra yotzei midey pshuto,” the Chazon Ish says –

David Bashevkin:

Meaning “ein mikra yotzei midey pshuto,” meaning a verse cannot be extracted from its plain reading.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Right, right. Which means what’s happening is that when Chazal make a drasha, when they derive from a pasuk, you can’t say that’s the original intentional meaning, but Chazal are using the creative powers to interpret the pasuk. And by virtue of they’re Chazal, Chazal can actually make a drasha and it can be an issur de’oraysa. But the drasha, the Halakhah, was created by the human intellect. So in other words, the essence of oral law is evolution. Every person who learns the Gemara and says their chiddush in the Gemara is in some sense evolving the oral law.

David Bashevkin:

They’re a part of Chazal too, in a way.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Right. So therefore it shouldn’t bother you. The fact that it’s not static just means that the essence of oral law is to evolve.

David Bashevkin:

And that authority to evolve, that authority to make those drashas –

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Was given to Chazal.

David Bashevkin:

Where do you see that deriving from.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

From Chazal, it’s “lo sassur,” according to Rambam it’s part of “lo sassur”. Part of what “lo sassur” is is that the Rambam says in the beginning of [inaudible] that drashas, gzeiros, minhagim, takanos, are all part of “lo sassur”. What “lo sassur” means is even though the Rambam says that the –

David Bashevkin:

“Lo sassur” is a verse in the Torah, meaning you shouldn’t stray from the interpretive powers.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Right. Even those the drashas the Rambam says they’re derabanan. It doesn’t mean they did it derabanan, they did it de’oraysa, but it’s generated by the rabbis, but the rabbis were given the authority by Hakadosh Baruch Hu of “lo sassur”. So basically, Chazal argue, by virtue of they derive new laws from pesukim based upon their authority to do so. And that’s the time it was given to Chazal, and that’s why the Torah law is actually effective and is authoritative for all generations. By virtue of the fact that the gedolim, the great Halachic decisors in every generation, are able to evolve the law. So your question is not really a question, because in other words, you’re looking at the oral law as something which is static. The oral law is in constant evolution.

David Bashevkin:

And theologically, I want to come back to two questions. Why was, I could see practically there were no refrigerators back then, but theologically, why is that so central to the essence of what our mesorah, our tradition’s, about?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Because the Torah’s eternal. The Torah’s eternal. The Torah is supposed to speak to every generation. How can the Torah speak to every generation without our ability to interpret it, the authority to interpret it in every generation?

David Bashevkin:

You must get, I mean you teach so many people who come not from Orthodox backgrounds where this is taken as a given. So how do you explain why, if there is this ability to evolve, if there is this ability to interpret, what separates, in the Orthodox denomination, and I’m not talking about your average young Israel rabbi, but what separates the senior rabbis within that denomination from other, more liberal, interpretive interpretations of the law?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

I’ll tell you why. If you look at the very, very, there’s a book written it’s called The Halakhic Process, I think by Joel Roth.

David Bashevkin:

Oh sure, I know who that is.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

You know that book, right. Very good. So Joel Roth explains that sometimes we have to basically reject Gemaras because they’re not relevant, the Halakhah really is not relevant. In fact even Joel Roth even says in one place in the book that many drashas of Chazal –

David Bashevkin:

Sure, we can make our own drashas, he suggests.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

No, more than that. Because our new knowledge of Semetic languages allows us to in fact actually to understand the verses completely. That’s the difference. In other words, I evolve the oral law, but the evolution of the law always has to be an interpretation of the Talmud. The concern is I understand I can drop the Talmud and evolve it. Not as an interpretation, that’s the difference. In other words, if you’re interpreting the Talmud, it remains, I’m evolving it, but it’s an interpretation. In other words, the evolution is rooted in the text.

David Bashevkin:

You’re always reacting to something fixed.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Right, but if I said –

David Bashevkin:

That’s the nature of interpretation.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

I say it as a passage in the Gemara that’s no longer relevant, I reject it for humanitarian or whatever ethical reasons today, that’s not called an interpretation.

David Bashevkin:

I’m sorry to come back to this, and again I’m only… isn’t that exactly that we’re saying about the science in the Torah? Isn’t that exactly? That’s why it troubles me. Isn’t that exactly what we’re saying about the passages that provide medicines in the Gemara? This is no longer relevant, that was just in there.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

I would say that those Gemaras who speak about medicines, I’m going to say this is going to sound controversial, I’m not sure that you make Birchas HaTorah on it.

David Bashevkin:

Yikes.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Right. In fact even –

David Bashevkin:

You don’t even consider that Torah necessarily?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

It’s some Chazal, but right. I don’t think that’s in the Torah, it’s not binding. In fact, actually there’s a Tosefta. There’s a Tosefta that says, I think it’s in Peah, “Ein lomdim halachos min aggadas.” Okay, this interesting thing. Why don’t we learn Halachas from the aggaditas? Because there’s different perushim. There’s a famous teshuva Nodeh B’Yehuda, siman kuf samach alef –

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

But parts of the Gemara, if I don’t learn Halakhah from it, it means that they are edified, but it doesn’t mean that they’re relevant. So aggaditas certainly are relevant, but I don’t want to learn Halachos from aggaditas. Okay, I don’t want to go into it, this is a big issue, [inaudible], et cetera, et cetera.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

But clearly even Chazal have acknowledged the fact, parts of the Gemara which I don’t learn Halachos, meaning what? Meaning that in fact Chazal themselves are acknowledging that certain things might not be relevant.

David Bashevkin:

So let me ask you, almost like that meta question, similar to what I asked before. When you ask yourself, the Chazon Ish writes this in countless places, that there’s some sense of providence in the way our canonization, the way our overall tradition worked. Do you have some theological explanation, what was the providence that allowed these, what I’m deeming less relevant or quasi-relevant passages in the Talmud?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Let me answer your question. Very interesting, the Chazon Ish’s lashon in Treifos, [inaudible], he speaks about the Gemara says in Avoda Zara that the world is going to be 6,000 years. 2,000 years tohu –

David Bashevkin:

“Tohu” meaning chaos.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

2,000 of what’s called Torah, and 2,000 years of yemos hamashiach, the Messianic era. And the Chazon Ish makes an interesting statement, in that hilchos treifos, where the Chazon Ish says that treifos would [inaudible] by Chazal based upon their science, so the Chazon Ish makes, this was sort of like, how should I say it, the Chazon Ish says that during the 2,000 years of yemos hamashiach things might change. Now, it’s very, very interesting, there’s a Gemara in Pesachim, in tzadi vav, there’s a dispute between chochma Yisrael and chochma umos ha’olam. How does this –

David Bashevkin:

The wisdom of the nations versus the wisdom of the Jewish people. I’m sorry.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

No, it’s okay. How does the sun go around the world?

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

So the chochma Yisrael say the sun basically goes like this on top, it makes a semi circle on top, and then goes up into the sky all over, but doesn’t go underneath the earth. In other words, it basically goes in the upper hemisphere, goes into the celestial sphere, and –

David Bashevkin:

And pops out.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

And pops out again, right? And actually, this is the basis of the shita of Rabbeinu Tam.

David Bashevkin:

Sure. Yeah.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Rebbe, [inaudible] says no, that the sun –

David Bashevkin:

Revolves around –

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Underneath. Says Rebbe, chochmei umos ha’olam are correct. Why, because the springs are warm at night. Which means Rebbe rules not like chochma Yisrael. Rebbe is at the end of the 2,000 years of Torah. The Chazon Ish understood at the time of Rebbe, that’s when there was a bifurcation between Torah and science.

David Bashevkin:

Meaning in this archetype, that we have 6,000 years, 2,000 years of chaos, 2,000 years of Torah, and then 2,000 years of Mashiach, it was Rebbe who was kind of the codifier of the Mishna, what did he do vis a vis scientific knowledge?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Well, I don’t want to into Rebbe in general, but we see that at this point of Rebbe, based upon what the Chazon Ish is saying, I’m bringing a raya from the Chazon Ish.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

And Rebbe, Rebbe’s the first Tanna to rule, to say that there’s a difference between the science of the nations and science of chochma Yisrael, and Rebbe rules like the scientists of the nations. Meaning this bifurcation takes place at the end of the 2,000 of Torah. Which means that basically, what I would read into the Chazon Ish, the Chazon Ish doesn’t say that, that in fact actually, during the 2,000 years of Torah, there was a commensurability between Torah and science. At the end of this 2,000 years, heralded by Rebbe, by Rebbe’s [inaudible] the Gemara in Pesachim, there’s a bifurcation between Torah and science. Which I understand is actually the authority. Rebbe’s Mishna is the basis of authority of the oral law. The Gemara is a commentary on the Mishna. So when the oral law becomes impacted and bases its authority, it bases its authority at a time that already science and Torah are not necessarily commensurable, and because of that we have to go back and try to understand what the sages say in terms of the way they looked at science, not the way we look at science. That’s –

David Bashevkin:

And let me return back to that theological question about the providence of the canonization, because that’s what you were getting at. Why, when you look at these passages of the Gemara, that you would not even make a birchas haTorah on, why do you think there was, again, assuming you believe in this notion or divine providence, you’ve quoted the Chazon Ish a few times, who really champions this as it comes to discovery of later manuscripts and in countless other places. What is the divine providence that allowed seemingly, again, less meaningful, I’m scared to call it meaningless, statements that were canonized in this treasured text?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

We don’t know, we don’t know. We don’t know what it is. I suspect that this commensurability of Torah and science bifurcated, broke down at this point, that’s when this thing happened, and therefore because of this, the canonization took place at that point. In other words, at a certain point, when the Torah was commensurable with the science of the world, then in fact actually that’s when in fact it was ultimately canonized.

David Bashevkin:

So personally, you are not bothered if you see that there are scientific developments that do not cohere –

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Not at all.

David Bashevkin:

With Talmudic wisdom.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Not at all, not at all, not at all.

David Bashevkin:

Not at all. So let me, I know your time is extraordinarily valuable, and I personally could talk to you for another 10 hours. When you are trying to introduce the Gemara and the uniqueness of what the Talmud is trying to do, especially because you’re teaching students who don’t have such a rich background, so I guess they can hold on tight to the roller coaster of your thought and ideas, but what is a book that you would recommend them to really appreciate this? Is there an English book that you would recommend?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Unfortunately not.

David Bashevkin:

Unfortunately, you don’t have anything?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Unfortunately not. Unfortunately, to teach a person how these things work, I think there’s a book that’s needed. But maybe the shiurim Naftali is giving, maybe that will come into a book. But a book like this is actually needed. I don’t think that really… Let me tell you something. I teach in Machon Shlomo –

David Bashevkin:

And that’s for people who don’t have a strong Jewish background.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Okay. Right, but they’re very, very bright.

David Bashevkin:

Extraordinarily bright. Ivy leagues, most of them.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

And most of the rosh kollelim, I teach, I have people who’ve learned in [inaudible], in Ponevezh.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

And they’re missing just as much as the boys at Machon Shlomo. In other words, many times what I have to teach the boys at Machon Shlomo is the same things I have to teach boys, avreichim.

David Bashevkin:

Serious Yeshivas.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

There is, the yeshivas, the curriculum in the yeshivas, put it this way: they don’t give the person a perspective, what I would call the meta-Halakhah. In other words, what are the rules that the Gemara was missing. This is something that is needed, and somebody’s going to have to write a book about this. I don’t know if people introduce this into the curriculum of the yeshivas, but I think it’s important. The gedolim knew these things, but I think this is important and really people should acquire such a knowledge, and how should I say it? There’s a need for a book, but this is right. Most people come out of yeshivas, even the best yeshivas, have absolutely no idea how the process works.

David Bashevkin:

Is there a Hebrew work that you would recommend to appreciate the meta-Halakhah?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

No. No, unfortunately not. Look, I’m not really in touch with all of the… But unfortunately not.

David Bashevkin:

Okay. Now –

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Most of the things that we’re speaking about, you have to be gleaning from different places.

David Bashevkin:

It requires kind of this intuition and deep immersion in the text themselves. Maybe that’s why it’s never taught, because to just kind of lay it out sequentially can be really, really difficult. Just a few quick, concluding questions, and I hope that we can speak more. If people want to find more of your thoughts and ideas, where can they find them?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

That’s a good question, I don’t know. I think a number of my papers were put on some type of a, there’s a Rabbi Triebitz, on the internet, if you look at Rabbi Triebitz I think someone collected a lot of my papers.

David Bashevkin:

Okay. And we’ll put that link up there, we’ll put that link up there.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Again, but if I can advertise, volume 27 of Hakirah magazine.

David Bashevkin:

Sure, the journal.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Right. So I edited quite a number of years ago lectures by Rabbi Soloveitchik.

David Bashevkin:

Sure. The Philosophical Lectures.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Right. So actually, the first five lectures actually came out in Volume number 27.

David Bashevkin:

Wow, we’ll put that link up there, sure.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

And actually, there’s 15 lectures all together, and they’re going to be published at the next Hakirah and the one after that. They’re going to come out. Whatever, I don’t –

David Bashevkin:

So this relates to that question, maybe you’ve already answered it. If somebody gave you a paid sabbatical to write a work, what do you think you would want to write about? I know you’ve been doing a lot of writing, it kind of trickles out and then comes out in streams over the years. But what are you most interested in writing and sharing with the world right now?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

I don’t know, on different things, I really can’t say one thing in particular. Are you talking about Halakhah, Hashkafa, what are you speaking about?

David Bashevkin:

Whatever, I’m curious what’s on your mind more than mine.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

There are a number of teshuvas that I would like to put out, I’ve had teshuvas published.

David Bashevkin:

Halakhik responsa.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Halakhik responsa, right. There’s a two volume work that was put out a few years ago called Orach Mishpat, and I have a teshuva there on hafka’as kiddushin which I think is a –

David Bashevkin:

On marriage annulment, which I assume you oppose to some degree.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

A teshuva of mine came out a few months ago about using cards in hotels.

David Bashevkin:

Oh, sure.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

That might be of interest to people. I have an article of the [inaudible] for the former Chief Rabbi of England, Jonathan Sacks.

David Bashevkin:

Sure, I’ve seen that article, on the formation of the Talmud.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

But what would I like to do? There’s different things. I think actually, if you Google Hakirah seminar, it was a seminar of Hakirah Magazine that was actually on Zoom.

David Bashevkin:

Online, yeah.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

And there, there were certain people who give talks on the philosophy of Rabbi Soloveitchik, on Halakhic mind, and I gave a 20 minute talk. I think that talk has to be expanded, and I think that will probably be the next article that I’m going to write.

David Bashevkin:

So let me ask you, you don’t have to answer this question, but I’m too curious not to ask.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Yes.

David Bashevkin:

You came from a background in Ivy Leagues, you studied mathematics, physics. At some point, you decided to immerse your life into Torah. What do you attribute that drew you to make such a serious change in the focus of your life, and your very clearly gifted intellectual powers, to dedicate it purely to Torah?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Ahavas Torah.

David Bashevkin:

You just loved it.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

That’s right. I was zocheh to do what I like to do.

David Bashevkin:

Is there a personality you would attribute who brought you to that love?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Well, I studied in Beis Yosef by Reb Yakov [inaudible], who knew kol haTorah kulah.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

But I think that like the Chazon Ish writes, in addition to those I happen to have known, my Rosh Yeshiva, I think when a person learns the Torah of the gedolim, the Chazon Ish, Reb Shlomo Zalman, Reb Yoshe Ber Soloveitchik, these are our rebbes. These are people who give us ahavas Torah. They inspire us, and it doesn’t have to be a rebbe that you actually learned from, you could learn from the sefarim, like the Chazon Ish says, [inaudible] is learning through the sefarim with the poskim. I think that this is a place which is a source of both inspiration and simcha, and this is I think what propels me to continue what I’m doing.

David Bashevkin:

Okay, final question, this is the most whimsical, I’m almost embarrassed to ask you, but I ask everybody. What time do you usually go to sleep, and what time do you wake up in the morning?

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Well, I daven vasikin.

David Bashevkin:

Okay, so it’s early.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

If you take about 45 minutes, an hour before netz hachama, that’s your –

David Bashevkin:

The rising of the sun, yeah.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

When I go to sleep, it depends. Sometimes I fall asleep early, sometimes I fall asleep. I don’t have a rigid, I should say, a rigid temporal schedule. If something keeps me away, I stay awake.

David Bashevkin:

And why am I not surprised with the energy of the way that you speak and your ideas, you don’t seem like somebody who has that rigidity of schedule. And it’s great that we get the gift of the excitement of your Torah, that’s a product of it.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Okay. Anyway, so that’s everything in a nutshell.

David Bashevkin:

Okay. It’s such a privilege.

Rabbi Meir Triebitz:

Actually I’m exhausted right now, but that’s another point. That’s a siyata dishmaya that in the many years I give shiur, I was never taught, even though I’ve come to Machon Shlomo many times very exhausted, once the shiur begins, I feel energized.

David Bashevkin:

Okay. Thank you so much for taking the time to speak, it really means a great deal, and it’s such a privilege and pleasure to speak with you today Rabbi Triebitz.

Leaving my conversation with Rabbi Triebitz, I think the central question is really a question that’s not about science and religion per se, but what is the Talmud? When we read through the Talmud and you come through passages that clearly don’t have relevance, how do you look at that, and what does that tell you, and how does that allow you to explore the larger question of what was done with the canonization of the Talmud? What is this body of knowledge, body of work representing for us? And I think it’s one of the most exciting questions in all of Jewish thought. I’ve always been enamored with the chaos of the Gemara, of the Talmud itself, and I think my conversation with him is a radical new lens to appreciate the large body of work, the Talmud, that has sustained Jewish thought, ideas, and practice through the centuries.

Thank you so much for listening. It wouldn’t be a Jewish podcast without a little bit of shnorring, so if you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe, rate, and review. Tell your friends about it. It really helps us reach new listeners and continue putting out great content. If you’d like to learn more about this topic, or some of the other great ones we’ve covered, be sure to check out 18Forty, that’s the number 1-8, followed by the word “forty”, F-O-R-T-Y.org. 18Forty.org. You’ll also find videos, articles, and recommended readings. Thank you so much for listening, and stay curious, my friends.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

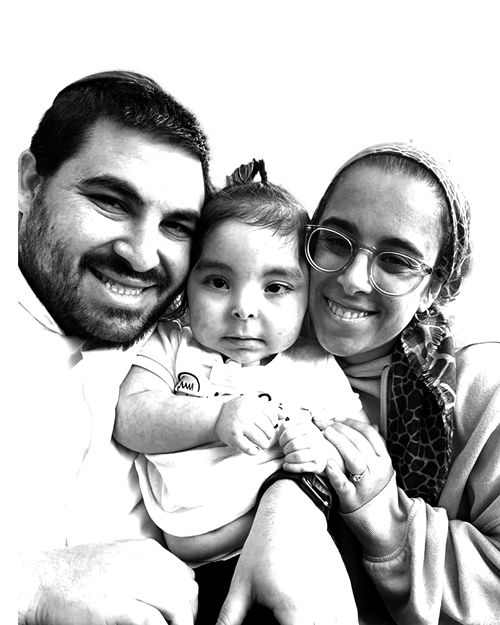

Hadas Hershkovitz: On Loss: A Husband, Father, Soldier

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Hadas Hershkovitz, whose husband, Yossi, was killed while serving on reserve duty in Gaza in 2023—about the Jewish People’s loss of this beloved spouse, father, high-school principal, and soldier.

podcast

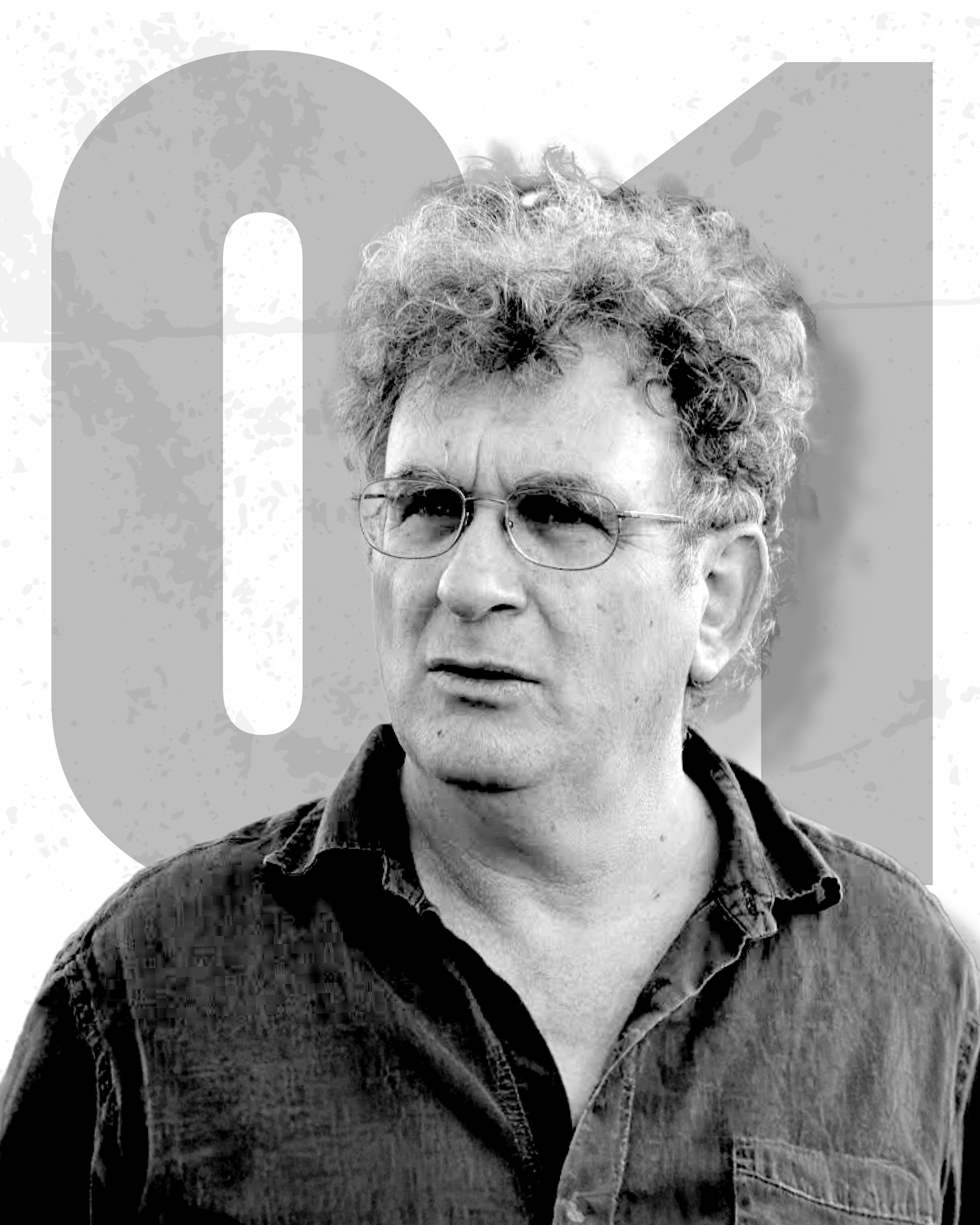

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Elissa Felder & Sonia Hoffman: How the Jewish Burial Society Cares for the Dead

Elissa Felder and Sonia Hoffman serve on a chevra kadisha and teach us about confronting death.

podcast

How Different Jewish Communities Date

On this episode of 18Forty, we explore the world of Jewish dating.

podcast

Red Flags: A Conversation with Shalom Task Force Featuring Esther Williams and Shana Frydman

We have a deeply moving conversation on the topic of red flags in relationships.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Shlomo Brody & Beth Popp: Demystifying Death and the End of Life

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Shlomo Brody and Dr. Beth Popp.

podcast

‘Everything About Her Was Worth It’: The Life of Yakira Leeba Schwartz A”H

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Yisroel Besser, who authored many rabbinic biographies and brought David Bashevkin to Mishpacha magazine, about sharing Jewish stories.

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Benny Morris: ‘We should have taken Rafah at the start’

Leading Israeli historian Benny Morris answers 18 questions on Israel, including Gaza, Palestinian-Israeli peace prospects, morality, and so much more.

podcast

Anshel Pfeffer: ‘The idea that you’ll obliterate Hamas is as realistic as wanting to obliterate Chabad’

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu did not surprise Anshel Pfeffer over the last 17 months of war—and that’s the most disappointing part.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Larry and Tzipora Rothwachs: Here Without You — A Child’s Eating Disorder

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Larry Rothwachs and his daughter Tzipora about the relationship of a father and daughter through distance while battling an eating disorder.

podcast

Anita Shapira: ‘You cannot wipe out Hamas’

Leading Israel historian Anita Shapira answers 18 questions on Israel, including destroying Hamas, the crisis up North, and Israel’s future.

podcast

Talia Khan: A Jewish Israel Activist and Her Muslim Father

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Talia Khan—a Jewish MIT graduate student and Israel activist—and her father, an Afghan Muslim immigrant, about their close father-daughter relationship despite their ideological disagreements.

podcast

Frieda Vizel: How the World Misunderstands Hasidic Jewry

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Frieda Vizel—a formerly Satmar Jew who makes educational content about Hasidic life—about her work presenting Hasidic Williamsburg to the outside world, and vice-versa.

podcast

Gadi Taub: ‘We should annex the north third of the Gaza Strip’

Gadi answers 18 questions on Israel, including judicial reform, Gaza’s future, and the Palestinian Authority.

podcast

Lizzy Savetsky: Becoming a Jewish Influencer and Israel Advocate

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Lizzy Savetsky, who went from a career in singing and fashion to being a Jewish activist and influencer, about her work advocating for Israel online.

podcast

Mikhael Manekin: ‘This is a land of two peoples, and I don’t view that as a problem’

Wishing Arabs would disappear from Israel, Mikhael Manekin says, is a dangerous fantasy.

podcast

Yishai Fleisher: ‘Israel is not meant to be equal for all — it’s a nation-state’

Israel should prioritize its Jewish citizens, Yishai Fleisher says, because that’s what a nation-state does.

podcast

On Loss: A Spouse

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Josh Grajower – rabbi and educator – about the loss of his wife, as well as the loss that Tisha B’Av represents for the Jewish People.

Recommended Articles

Essays

This Week in Jewish History: The Nine Days and the Ninth of Av

Tisha B’Av, explains Maimonides, is a reminder that our collective fate rests on our choices.

Essays

I Like to Learn Talmud the Way I Learn Shakespeare

If Shakespeare’s words could move me, why didn’t Abaye’s?

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

Fighting for My Father’s Life Was a Victory in its Own Way

After losing my father to Stage IV pancreatic cancer, I choose to hold onto the memories of his life.

Essays

Books 18Forty Recommends You Read About Loss

They cover maternal grief, surreal mourning, preserving faith, and more.

Essays

Benny Morris Has Thoughts on Israel, the War, and Our Future

We interviewed this leading Israeli historian on the critical questions on Israel today—and he had what to say.

Essays

Why Reading Is Not Enough for Judaism

In my journey to embrace my Judaism, I realized that we need the mimetic Jewish tradition, too.

Essays

A Letter to Children Estranged From Their Parents

Children cannot truly avoid the consequences of estrangement. Their parents’ shadow will always follow.

Essays

‘The Crisis of Experience’: What Singlehood Means in a Married Community

I spent months interviewing single, Jewish adults. The way we think about—and treat—singlehood in the Jewish community needs to change. Here’s how.

Essays

3 Questions To Ask Yourself Whenever You Hear a Dvar Torah

Not every Jewish educational institution that I was in supported such questions, and in fact, many did not invite questions such as…

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

Do You Need a Rabbi, or a Therapist?

As someone who worked as both clinician and rabbi, I’ve learned to ask three central questions to find an answer.

Essays

Between Modern Orthodoxy and Religious Zionism: At Home as an Immigrant

My family made aliyah over a decade ago. Navigating our lives as American immigrants in Israel is a day-to-day balance.

Essays

Do We Know Why God Allows Evil and Suffering?

What are Jews to say when facing “atheism’s killer argument”?

Essays

The Erasure of Sephardic Jewry

Half of Jewish law and history stem from Sephardic Jewry. It’s time we properly teach that.

Essays

From Hawk to Dove: The Path(s) of Yossi Klein Halevi

With the hindsight of more than 20 years, Halevi’s path from hawk to dove is easily discernible. But was it at every…

Essays

Judith Herman Is Giving Voice to Survivors

Dr. Judith Herman has spent her career helping those who are going through trauma, and has provided far-reaching insight into the field.

Essays

‘Are Your Brothers To Go to War While You Stay Here?’: On Haredim Drafting to the IDF

A Hezbollah missile killed Rabbi Dr. Tamir Granot’s son, Amitai Tzvi, on Oct. 15. Here, he pleas for Haredim to enlist into…

Essays

The Hardal Community Explained: Torah, Am Yisrael, and Redemption

Religious Zionism is a spectrum—and I would place my Hardal community on the right of that spectrum.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits’ Complicated Portrait of Faith

Meet a traditional rabbi in an untraditional time, willing to deal with faith in all its beauty—and hardships.

Essays

How and Why I Became a Hasidic Feminist

The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s brand of feminism resolved the paradoxes of Western feminism that confounded me since I was young.

Essays

When Losing Faith Means Losing Yourself

Elisha ben Abuyah thought he lost himself forever. Was that true?

Recommended Videos

videos

Mysticism

In a disenchanted world, we can turn to mysticism to find enchantment, to remember that there is something more under the surface…

videos

18Forty: Exploring Big Questions (An Introduction)

18Forty is a new media company that helps users find meaning in their lives through the exploration of Jewish thought and ideas.…

videos

Talmud

There is circularity that underlies nearly all of rabbinic law. Open up the first page of Talmud and it already assumes that…

videos

The Hasidic Rebbe Who Left it All — And Then Returned

Why did this Hasidic Rebbe move from Poland to Israel, only to change his name, leave religion, and disappear to Los Angeles?

videos

Did Judaism Evolve? | Origins of Judaism

Has Judaism changed through history? While many of us know that Judaism has changed over time, our conversations around these changes are…

videos

Jonathan Rosenblum Answers 18 Questions on the Haredi Draft, Netanyahu, and a Religious State

Talking about the “Haredi community” is a misnomer, Jonathan Rosenblum says, and simplifies its diversity of thought and perspectives. A Yale-trained lawyer…