Lawrence Schiffman: The World of Early Judaism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Professor Lawrence Schiffman about Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism.

Summary

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Professor Lawrence Schiffman about Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism.

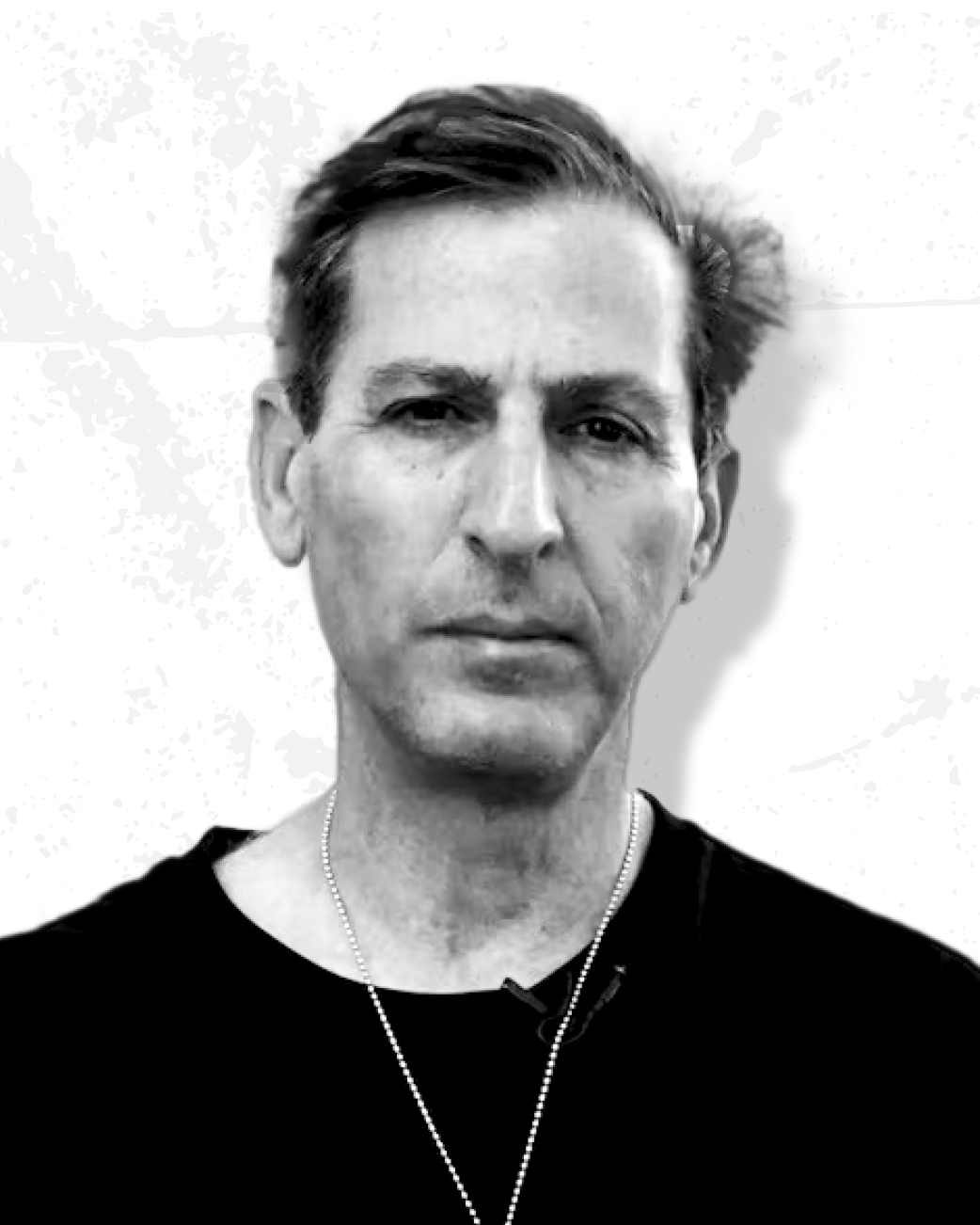

Lawrence Schiffman is a professor at New York University, where he lectures on topics such as the Dead Sea Scrolls, Midrashei Halacha, and Second Temple Judasim. He joins us today to discuss the evolution from early Judaism to modern observance, as well as the outcomes of superimposing ancient Judaism onto our present day understandings.

- Who is a “common Jew”?

- Is Jewish disunity as modern as we think it is?

- Why would one cling to modern Judaism despite its evolution over history?

Tune in to hear a conversation on the development of Judaism and how faith must be the answer when history fails us.

Interview begins at 23:48

Lawrence Schiffman is a professor of Hebrew and Judaic Studies at New York University and Director of the Global Institute for Advanced Research in Jewish Studies. Dr. Schiffman is a specialist in the Dead Sea Scrolls, Judaism in Late Antiquity, the history of halacha, and Talmud. He has served as Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education and Professor of Judaic Studies at Yeshiva University. Dr. Schiffman was featured in the PBS Nova series documentary, Secrets of the Dead Sea Scrolls, and several other documentaries. Dr. Schiffman’s book, From Text to Tradition, is a journey through the history of the emergence of rabbinic Judaism in the Second Temple era. Dr. Schiffman joins us to talk about the world of Early Judaism.

References:

“The Rambam’s Introduction to the Mishna” by Maimonides

Zakhor: Jewish History And Jewish Memory by Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi

The Formation of the Talmud: Scholarship and Politics in Yitzhak Isaac Halevy’s Dorot HaRishonim by Dr. Ari Bergmann

Dorot HaRishonim by Rav Yitzhak Isaac Halevy

“Wissenschaft Des Judentums, Historical Consciousness, and Jewish Faith: The Diverse Paths of Frankel, Auerbach, and Halevy” by David Ellenson

From Text to Tradition, a History of Judaism in Second Temple and Rabbinic Times: A History of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism by Lawrence Schiffman

Josephus: The Complete Works by Flavius Josephus

Comparing Judaism and Christianity: Common Judaism, Paul, and the Inner and the Outer in Ancient Religion by E.P. Sanders

The Four Stages of Rabbinic Judaism by Jacob Neusner

Der Babylonische Talmud by Lazarus Goldschmidt

Sefer HaIkkarim by Rav Yosef Albo

Texts and Traditions: A Source Reader for the Study of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism by Lawrence Schiffman

Sefer HaChinuch by Anonymous

Transcript

David Bashevkin:

Hello, and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast, where each month we explore a different topic balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host, David Bashevkin, and this month we’re exploring the origins of Judaism. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big, juicy Jewish ideas, so be sure to check out 18Forty.org, where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails.

I really need to level with our audience, and this happens often. I am absolutely… terrified’s a strong word. I am very nervous about this subject, and I want to tell you why. First and foremost, obviously the origins of Judaism more than anything else, it sounds a little bit boring.

I think for most of our audience, especially for people who are tuning in and listen to our series on teshuva or on intergenerational divergence, the types of issues that bring you to 18Forty, that you’re most excited about, are probably issues that relate to sociological dissonance, emotional dissonance, that friction, that lack of satisfaction, that lack of inspiration that we may feel in our Jewish life. And this is decidedly not one of those subjects.

This is a little bit more academic, dare I say intellectual, one of those issues that deal with the tenets of our theological faith, the emergence, so to speak, of Rabbinic Judaism, a phrase which we will get to in just a moment. So more than anything else… not more than anything else, but one of the things that I’m most nervous about is like, “Hey, I’ve been listening. I love your stuff.” And then you’re like coming to this subject like, “Not this.”

One of the joys of 18Forty is the fact that we cover different forms of issues. Some of the issues that we cover are about sociological dissonance, about communal issues. We’ve discussed abuse in the community, we’ve discussed issues related to parenting in the community. We discuss communal issues, this sociology, so to speak, of the Jewish community, and of course we discuss emotional issues, finding that satisfaction, reinventing, reimagining your religious commitment.

But we also discuss theological dissonance, and we try to do it in a substantive, somewhat accessible, an accessible and substantive way. We’re not looking to build walls, we’re trying to provide content, information, ideas that help people reconcile and find a way through to build their own Jewish commitment in the modern world. So, if this is a little bit boring and it’s not that interesting to you, I don’t know what to tell you. I feel bad. It’s always something that worries me a little bit. Feel free to go into the archives. You could take a break, stretch your legs for a month or so. Please, don’t hold it against us and don’t say I didn’t warn you.

But there’s another reason, and this is really the main reason why I am nervous to talk about an issue as lofty, as weighty, as serious as the origins of Judaism. And that is, when you deal with the tenets of our faith, with theological issues, you have to proceed very, very carefully, and these are issues that are absolutely fraught with ideas and concerns that could, God forbid, erode somebody’s commitment to Yiddishkeit.

And everything that we try to do on 18Forty is the opposite of that. We’re not looking to erode people’s commitment; we’re looking to build people’s commitment. And I say that unapologetically, though we don’t engage in apologetics in the same way that may be discussed on other sites. I really try to engage and understand the ideas and find the way through.

I’ll apologize in advance. This intro, odds are, is going to be a little bit longer. We had an anonymous conversation, but I really want to frame the issue more deeply before we dive in. So, apologies in advance if you hate the long intros. We always list on the website and in the emails when the actual interview begins, so feel free to skip to that. But if you skip the intro, you’re not allowed to write angry emails. Angry emails are only from people who listen to the long intros.

But before we even launched our first interview, I already got an email. It was not a vicious email, it was an email from somebody who was very concerned, and I want to read it to you. They watched the opening video framing this topic on 18Forty and wrote as follows. “The very term Rabbinic Judaism is itself fraught with meaning. Those who refer to it are frequently those who would deny the divine origin of Torah she’baal peh, the oral law. That goes for the Wissenschaft scholars.” Wissenschaft is a fancy German word, which we will obviously be discussing in the series, which was the scientific study of Judaism, the way that historicized Judaism to find out, how did this actually develop? “That goes for the Wissenschaft scholars of the 19th century and others of that school of scholarship at the Reform and Conservative seminaries.”

I think the person who wrote the email is absolutely right. The very term Rabbinic Judaism is itself fraught with meaning, and it’s a hard term to avoid and it is one that I do in fact use on these interviews and in this conversation. And I want to explain, though we will come back to it, what I do and do not mean by that. And this returns to the ideas that we presented in that opening video. I don’t know if you got a chance to look at it. We’ve really been trying to launch and build up our YouTube channel, which you can check out. 18Forty on YouTube, make sure to smash that subscribe button.

But we always launch a video before every topic that tries to frame the conversations that we are having beforehand. And essentially the term Rabbinic Judaism and why it is fraught is because it is highlighting a change that we see, that you can see, that not everybody agrees to, between the Judaism that we see described in Tanach, in Torah, Nevi’im, Kesuvim, in the Torah and the writings of the prophets and in the later writings, and the Judaism that we see described in the Talmud. There are emphases that we see absent in the writings of the prophets. We don’t see the world of halacha emphasized in the same way that we see it in the world of the Talmud and the world of the Gemara.

And for most people it doesn’t necessarily bother them. They may not necessarily even see those differences, because the only way that they’ve engaged in the study of Tanach and the study of writings of Judaism in the Second Temple period is through the lens of the Talmud. So, they’ve never really engaged with it on its own terms, and therefore they don’t really see any change. But in fact, there have been significant changes, and I’m using that word carefully. Changes in maybe what is prioritized and what is central in the stories.

I think the role of talmud Torah is not something that we find emphasized in Tanach in the same way that we see it emphasized in later writings. I think the centrality of halacha seems to be different in the way that we see it in the writings of Nevi’im and Kesuvim and the way we see it in later writings.

Now, these differences, I’m not the first person to notice them. People have noticed them both from the school of Wissenschaft des Judentums, I don’t know if I’m pronouncing that correctly, which is that fancy German word for the scientific study of Torah. And there are people who have noticed these differences who fit squarely very much within the traditional camp, figures like Rav Tzadok HaKohein m’Lublin, figures like Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook, figures like Rav Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin also known as the Netziv.

All of these writers, Rav Kook, Rav Tzadok and the Netziv, who all lived in that same time… Rav Kook lived a little bit after, but all in that same late 19th, early 20th century period, also wrote about these changes and how the development and emergence of the Judaism we know today came about, how rabbinic authority as we currently conceptualize it first emerged.

Essentially, I believe, and this is something that we emphasize in that opening video, but something that I want to frame because it plays a role throughout our conversations, there are really three models as I understand it to how you approach these changes. The first model is projecting the present onto the past. The second model is projecting the past, superimposing an imagined past, onto the present. And the last model is what I would call the development model. Now let me go through each one and explain exactly what I’m talking about.

The first model projects the present onto the past. We take the current models of rabbinic authority, what we understand through the Gemara and Judaism as we understand it through the Gemara, and we project that onto the entirety of Jewish history. This is what it was like in the time of Moshe Rabbeinu, this is what it was like throughout the Second Temple period. You could imagine that Yeshivas Shem v’Ever, you know, the biblical yeshiva that we see mentioned in sefer Bereishis, I know I certainly was like this, that you could imagine what that yeshiva was like.

It would be like walking into Lakewood. And I don’t just mean with people learning with white shirts and black pants and shuckling over a passage of Talmud, but the locus of Torah learning was always central. The way people related to divinity, that people related to God in the Jewish community was always the same. It’s always what we have now, and the way that we relate to Tanach is through the prism of the Gemara and through the Rishonim and through the Acharonim and through all later commentaries. It is how we take and build continuity from the present and connect it to the past.

Now, there is a lot of truth to this model. There is absolutely continuity. The notion of divine revelation is obviously predicated on that, and the notion of the mitzvos that we have. But is there room for evolution? Now this is something that the Rambam discusses in his introduction to the Mishna, which actually allows for a great deal of evolution. In that email I got, the writer, whose name I don’t need to mention, and I don’t think he was after… I think it was somebody who was quite educated and concerned for all the right reasons.

He followed up and says, “The Rabbinic Judaism concept seems to take the stance that somehow, this is a new era in the evolution of Judaism, not a continuation of the mesorah m’Sinai, the tradition from Sinai that involves so many characters of biblical Judaism.”

We’ll get to people who talk about this break. But in a sense, there is a new era of evolution in Judaism. I’m not the first person to say this. This is more or less the way Rav Tzadok understands this distinction, in that our locus in how we relate it to HaKadosh Baruch Hu, to God, the emphases of Judaism did undergo a change following the cessation of prophecy and the destruction of the Temple.

Where once Judaism was prophetically centered, and shifted to a relationship with God that was born from human creativity and human interpretation, that doesn’t mean that there is not divinity underlying that human interpretation, but it does mean that there is a component of evolution and interpretation in the development, the flowering so to speak, of the oral law. And that is something that I am not afraid to say, but in the first model, it emphasizes by projecting the present onto the past, “This is always how it was. It tries to limit the amount of evolution that took place, so the growth and the continuity feels rather sequential.

Now, there’s a reason why we emphasize this, and some of the people who have emphasized this, like in the writings of Rav Shamshon Raphael Hirsch, who in his dialogue with his old friend Abraham Geiger, who we will get to in a moment, wanted to emphasize the sense of continuity. Some may say, if you read him carefully, that he overemphasized how similar and how sequential it has been, and underemphasized the amount of interpretation that takes place.

All you need to do to realize that is to read, as I mentioned, the Rambam‘s introduction to his commentary on the Mishna, which it is clear from that that most of the drashes that we have were a product not of divine revelation and prophecy, but were a product of human creativity and interpretation. That’s most of what we have in front of us, and every generation was able to interpret that. Now the principles of those interpretations are certainly divine, but there was an element of human creativity and interpretation. It’s part of the beauty of our tradition, at least in my eyes.

That’s the first model. The first model is taking the present and projecting it onto the past. There’s a second model, and that second model was championed by Abraham Geiger, one of the first leaders of Reform. And that is taking the imagined or the historicized past and trying to project it onto the present. “Let me try to go back and dig down, almost an archeological excavation to find some pristine Judaism that predates the Talmud and superimpose that onto the present.”

It’s essentially what Geiger did. Geiger believed the Talmud, or what I believe he called Talmudic Judaism, which is obviously a fraught term, but the Judaism as we understand it through the Talmud, the oral law and the interpretations of each generation, had corrupted a pristine model of ethical monotheism that existed in prophetic times, and kind of buried it under the minutia of halacha and tradition and the interpretations of each generation.

And what he advocated for in early Reform Judaism was to excavate that pristine model of ethical monotheism and reemerge it and bring it out from underneath the rubble as he saw it, as he saw it, of Talmudic interpretations throughout the generations and reinstill that at the center of Judaism. This caused, obviously, a great uproar, and rightfully so. It didn’t come with a great deal of deference for the tradition as preserved throughout the generations, and secondly, it brought Judaism a great deal closer to Christianity. He actually blamed Christianity and the persecution throughout the generations for the reasons why Talmudic Judaism emerged, and the Christians were also upset at him. So everybody was angry at Geiger.

But I think what underlies some of the difficulty of Geiger is, he essentially wants to take that past and superimpose it on the present, and looking at millennia of Jewish interpretation and engagement with Torah learning, and say, “That’s not the development, that’s not the beauty, the harmony, the melodies of Yiddishkeit unfolding and divinity sprouting up through the creativity of the collective Jewish people of the generations.” But rather, as he saw it, it was a corruption.

So he advocated for something else. He said, “Let’s go back to that beginning. Let’s go back to ethical monotheism.” And that’s why there’s such a push and such a hesitance, and why I understand why even before we dropped our first interview, we got an email saying the term Rabbinic Judaism is fraught. Because it calls to mind that second model of people who looked at rabbinic interpretation as a corruption, rather than this incredible model, as I see it, of preserving Yiddishkeit, preserving divinity, throughout the generations and throughout history.

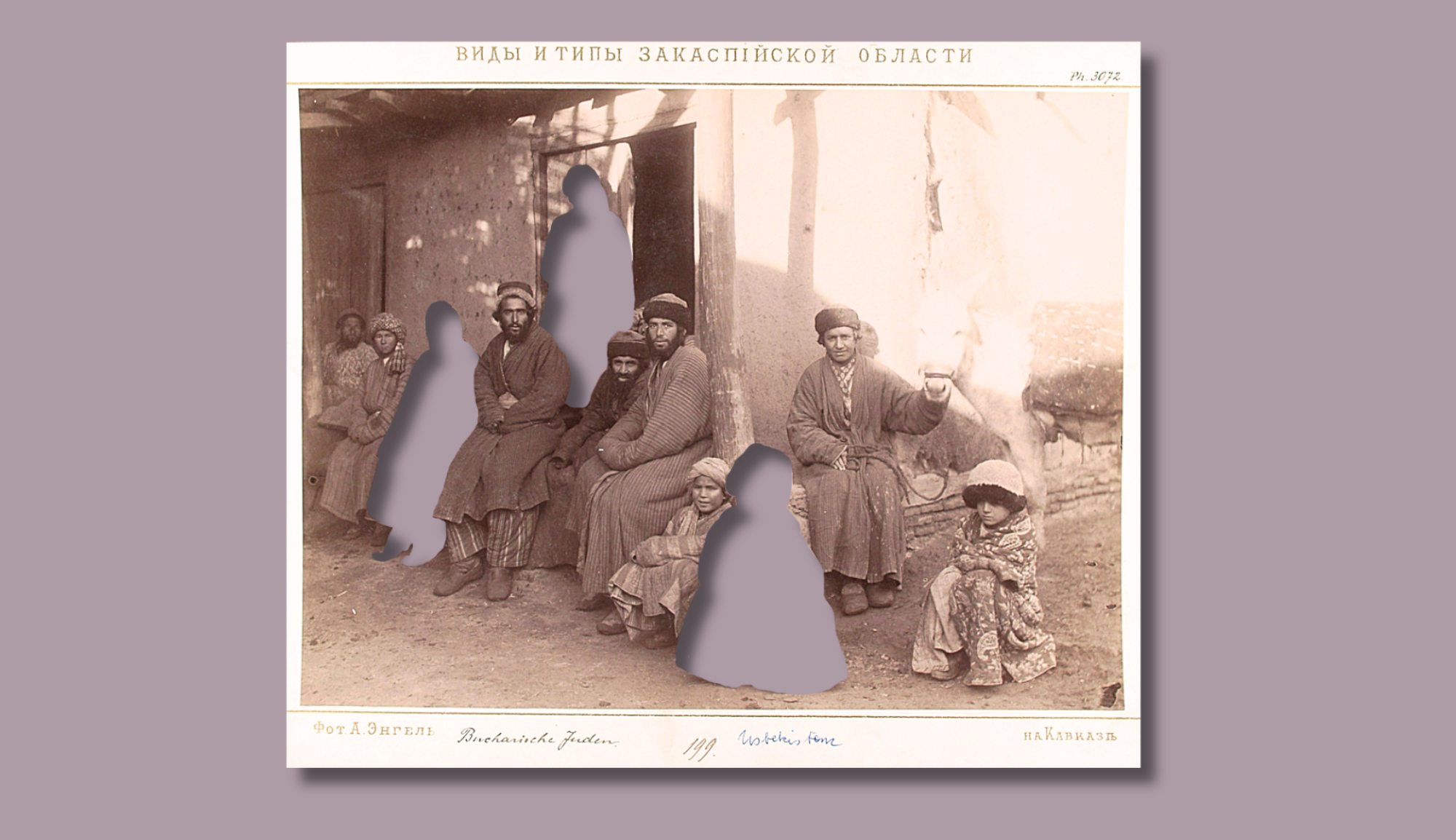

For much of Jewish history, as Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi writes in his absolutely essential book Zakhor… and I recommend that everybody must read that if you haven’t read it already. It’s not a long book, it’s very short. He was the Chair of Jewish Studies at Columbia. He writes that for most of Jewish history, Jews were not even concerned with Jewish history.

So a lot of these conversations that emerged in the 19th and 20th century from the scientific study of Judaism, we hadn’t really spent time figuring out what was historical and what developed when. Everything was preserved not through Jewish history, but through Jewish memory. It was in the living present that all generations were given expression through Jewish tradition. It’s the Yiddishkeit, in many ways, that I still try to live, and why the mesorah, the tradition of Yiddishkeit, is so moving to me.

But once there was this push ushered in by Geiger and later scholars to figure out really the history and the development of each generation and accusing tradition of being a corruption rather than an expression of divinity, more traditional leaders needed to respond. And that really gave way to this golden age of both historical responses from the traditional camp and reconceptualizing the change itself. And they were two separate movements.

On the one hand, there were scholars like Rav Yitzhak Isaac Halevy, who my teacher and former two time 18Forty guest Rabbi Dr. Ari Bergmann wrote his book on called The Formation of the Talmud: Scholarship and Politics in Yitzhak Isaac Halevy’s Dorot HaRishonim, one of the most riveting books I have ever read, which talks about the politics that went into the exploration of Jewish history, which was fraught as our email writer mentions, but also went in to build up all of Jewish history, not just the history of the Talmud, but starting in biblical and prophetic times in the Second Temple.

And in the introduction to his work, Dorot HaRishonim, which is the earlier generations, which is really a history of the Jewish people, but using a lot of the tools of the scientific study of Judaism, he received an approbation from probably the greatest living traditional rabbi at the time, Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzinski. And Chaim Ozer writes in his approbation that this is so necessary right now, because so many others have written histories of the Jewish people that frame tradition as a corruption, and we need somebody who can use these tools and put them to use to in fact show that our tradition is, God forbid, not a corruption of Judaism, but the greatest expression of Judaism.

And he did a fairly admirable job, though if you read Ari Bergmann’s book, or there’s another fantastic article that was written by David Ellenson who is a scholar of this period of the confrontation with modernity, I think it was an article or a pamphlet, it’s called Wissenschaft des Judentums. I don’t know if I’m pronouncing that right, so you could giggle. Mel Barenholtz, if you’re out there, send me letters, because I know I’m butchering it. Wissenschaft des Judentums: Historical Consciousness and Jewish Faith, The Diverse Paths of Frankel, Auerbach, and Halevy, where he talked about these three different scholars, Halevy being the traditionalist of the group, who tried to take the tools of the academic study of history and apply them to Judaism itself.

And this wasn’t done, because as I mentioned and as Yerushalmi emphasizes, until then Jews preserved their faith and their history through memory. And in many ways, if given a choice, I think that’s the best way to preserve it, in your living memory. But the problem is, especially nowadays when you are confronted by so many questions, when we have access to so much more, how do we in fact ground our faith?

You know, I’ll be honest for a moment. We opened up with an anonymous interview. There was another anonymous interview that I was desperate to get. There is somebody I know, I’m not going to say where he lives or anything about him but suffice to say he is a massive talmid chacham. He is a massive scholar in the most traditional way, who these very issues absolutely plagued him. And I begged him to come on and share a little bit.

This is somebody who has written very serious sefarim. Again, I don’t want to say more. I’m not making up to who this person is. And I begged him to come on, and he went back and forth, and he didn’t feel comfortable for a lot of personal reasons that I absolutely respect and understand. But these are very real issues that people grapple with and need adequate responses and to be pointed in the right direction. And I hope that I’m going to be able to do so. Which really leads me to the third model.

If the first model is taking the present and projecting onto the past, and the second model, championed by Geiger and frustrating all the traditionalists, which is assuming this idealized past and superimposing it onto the present, there is a third model, which acknowledges that something changed, which acknowledges that something is different, but explaining why that change was necessary.

And there were many people who championed this who absolutely emphasize that there is something different. If you go back and you read literature describing the Second Temple period, the First Temple, it does look different, it does sound different. It’s not necessarily the same… and I’m going to use the word that we don’t like, but let’s say it anyway. It’s not the same Rabbinic Judaism that we may be familiar with today.

Something did change, and these again were figures like Rav Tzadok HaKohen of Lublin. These were figures like Rav Kook. These were figures like the Netziv, who all intuitively understood that something did in fact change. Their response was not necessarily to use the tools of academic and historical study and turn it on Judaism. What they in fact did was, both within the system of tradition but using theological principles, explaining why a change was absolutely necessary.

As we will discuss in later episodes, some emphasize the differences between the written law, what’s known as Torah she’bichsav and Torah she’baal peh. Some talk about the shift not of the written to oral, but the shift between a prophetic model and an interpretive model. That once prophecy stopped, the very fabric and character of Judaism evolved and changed.

Some use even greater theological terms, where they talk about the paradox of divine foreknowledge and free will, and talking about creating a Torah that both includes the divine foreknowledge and that kind of blueprint for the world that encompasses everything that exists in our written Torah, and the human creativity that emerges from our free will to reconstruct, so to speak, and wed together that often paradoxical worlds of divine foreknowledge and free will, and wed them together in this union of divinity and human interpretation.

But all three of these models are important to know, and to know that they’re in dialogue with one another. And very often when people get upset, they don’t appreciate which model is speaking. I’m going to leave the guessing game behind, and I usually don’t take a strong position, but I want to avoid being excommunicated or having pashkevilim. Those are those signs that are hung up. I’m not going to avoid it entirely, but I’ll tell you exactly what camp I am in.

I am squarely in the third camp. I am in the school of Rav Tzadok, of Rav Kook, and the Netziv, who appreciate that something changed, appreciate an element of evolution and development, use whatever adjective or verb you want, but they recognize that something changed, but they appreciate that it is divinity that is the foundation throughout. So, it’s really taking elements of both the first and second model. If the first model is emphasizing only divinity and the second model is emphasizing only change and human interpretation, I think the third model kind of weds them together.

Yes, there was a change. Yes, there has been development. But there is a way to see and actualize divinity throughout that entire process. And that is why I am absolutely in love with the study of Talmud, because I think it is the lens through which we engage with the grand symposium, the collective ideas of Knesses Yisroel and the Jewish people. And I hope it’s on this journey that you join us with 18Forty, that we can add our collective voice to that journey in confronting the questions of history, but also building a greater commitment and appreciation within our collective memory.

And it is without further ado that I would now like to introduce our conversation with really an expert in the field, the author of the absolute classic From Text to Tradition: A History of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism, a professor at NYU. It is our absolute pleasure to introduce our conversation with Professor Lawrence Schiffman.

It is really my absolute pleasure to be sitting today with Professor Lawrence Schiffman, who I really know because my teacher, dare I say rebbi in Yeshiva University, why I came to study in Yeshiva University after learning in Ner Yisroel for many, many years was Dr. Yaakov Elman of blessed memory. And I know he spoke so fondly of you. We studied together for two years, we learned the works of Rav Tzadok together, which in some tangential way relates to our discussion today. Thank you, Professor Schiffman, for joining us today on 18Forty.

Lawrence Schiffman:

Thank you. Good to be with you.

David Bashevkin:

I want to begin with really a framing of the question. And that is, when we look at the Jewish community today and you ask your average Jew, “What’s the Jewish community up to?” they’re going to break it down into denominations. They’ll tell you we have an Orthodox community, we have a Conservative community, Reform, Renewal, Reconstructionist, and we have all of these different denominations.

And when we talk about the emergence of Judaism as we know it today, we try to all draw straight lines back to the past. Orthodoxy for sure does this. There are spirits of Conservative Judaism that contends with the past. Reform Judaism tries to restore a past. And my question is, if I were to ask a Jew in the Second Temple period, which is your expertise, “What is Judaism today?” are they describing the different sects of Judaism in the same way that we talk about Reform, Conservative and Orthodox today? Were they interacting in the same way? And what were the beliefs of these sects?

Lawrence Schiffman:

Okay, this is like a question which could take up all of our time. So, let’s start by explaining. There is actually only one Jew who we know answered that question explicitly. That Jew who answered the question explicitly was Josephus. Now Josephus was writing, really, after the destruction of the Temple, but was writing about the situation right after the Maccabean Revolt.

Now, after the Maccabean Revolt for Josephus doesn’t mean what it means to most people today. Most people today think in 164 BCE, Jerusalem was liberated and that’s the end of it. But for Josephus, who understood that Judah the Maccabee and his followers were subsequently kicked out by Hellenists, and that really the Maccabean Revolt ended 152, when Jonathan the Hasmonean became the ruler. So it’s that point exactly Josephus says there are three major Jewish sects, and he tells us about the Pharisees, the Perushim, who were the forerunners of Talmudic rabbi-

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, so tell us, what are those three big sects that he says?

Lawrence Schiffman:

So the first one he talks about is the Pharisees, Perushim in Hebrew, the forerunners of the Talmudic rabbis. And he describes them and talks about aspects like the unwritten law, which is a kind of free version of what we call Torah she’baal peh, the oral law, and he talks about the Pharisees as popular teachers. And then he goes on to discuss the Sadducees, who are the high priestly sect, very much involved with the aristocracy. And here he indicates that the Sadducees actually believe that the world was basically not under divine control anymore.

And he basically pictures them as actual Epicureans, not the way the term is used in Hebrew for apikorsim, but actual Epicurean philosophers. And then he goes on to talk about the Essenes, who many identify with the Dead Sea Scroll sect, but he talks about the Essenes as a group that believes in fate, and yet at the same time they have this entire religious sectarian life that they’ve separated from the others for higher standards of purity. And basically, he sets forth these as the three major groups.

Now, we should comment right off the bat that some of these groups that he describes have subgroups. He talks about the Essenes as having marrying and non-marrying Essenes. And there’s another group that he talks about later on called the Fourth Philosophy, which is the extreme rebels. And these extreme rebels end up dividing into, as far as we know, about six different groups. So, Josephus is clearly generalized, but his point is, it’s sort of like the guy who says, “Today we have Reform, Conservative, and Orthodox,” and makes that kind of generalization.

David Bashevkin:

Do we have any assessment of the majority… We have Pew reports, so we know who, so to speak, is the largest group in America, the largest group in Israel. Do we have any sense, if you were to go back, meaning what the population breakdown was?

Lawrence Schiffman:

Well, we don’t really have a sense of that. In fact, by the way, we don’t even know what the population was. There are all kinds of disagreements about what the population was. But what I think we can say about this is that we have to remember that most people were unaffiliated, but not unaffiliated the way it means today.

Unaffiliated today is below the level of participation. Most people constituted what now, after the work of E.P. Sanders, is called common Judaism. Common Judaism is what most people did. They went to the Beit HaMikdash maybe only once a year, even though there were three opportunities. They were eating kosher food, they were keeping Shabbat, and exactly whom they were following, it’s not so clear, but these people were the common Jews, and the members of these groups were minorities that were basically competing with one another to gain the support of the common Jews.

Now Josephus says that the most popular group was the Pharisees, but they give numbers like 4000 Pharisees. Not because that’s the total population, but rather because you have all these people who are following the Pharisees, and he says that they were the majority group. Now this certainly seems to be correct if you look at what happens at the end, because after destruction of the Temple, the other groups are virtually out of business. And the Pharisees, who become the Talmudic rabbis, they are the only group left standing. So, it’s hard to believe that that’s the case if they were not getting a lot of support the way Josephus explains along the way.

David Bashevkin:

Can I ask you just another question about the common Jews? To me, a lot of Jews nowadays, even if they belong to an institution or a synagogue, probably could be described in a way as a common Jew. They don’t know the doctrine necessarily of the movement that they belong to. A common Jew in this period, you said they are keeping Shabbat. What on earth does that mean? If the law was not canonized at that time and disseminated like we have it where you could Google it, you could look it up in so many texts, what did it mean to a common Jew that they were keeping Shabbos?

Lawrence Schiffman:

Well, if you take the Shabbos example, we have from Second Temple times, probably, I’ll explain in a minute why I say probably, three lists of things that are forbidden on Shabbat, as to what is work, what is melacha on Shabbat.

Now the one list is in the book of Jubilees, which is a Second Temple work which shares in the priestly-like approach of the Dead Sea Scrolls, and was preserved there in some fragments. Then we have the actual Dead Sea Scrolls list of what is forbidden on Shabbat. And then we have the 39 rabbinic list, which I think goes back to Second Temple times or very close to it, because it’s so much like those other lists that I just mentioned.

David Bashevkin:

What we call the lamed tes melachos.

Lawrence Schiffman:

Yeah, they have tremendous amounts of things in common. Let me just give you an example. The first law in the Dead Sea scrolls one, which I’ll tell you by the way was analyzed by me in my doctoral dissertation, a whole big section was on the Shabbos laws of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The first law is that when the sun is distant from the horizon by its own diameter, which is about 40 minutes before sunset, that you stop doing melacha. And then they quote the very same text that the rabbis quote. Right? They quote “Shamor et Yom HaShabbat l’kodsho.” “Keep carefully the Shabbat to sanctify it.” From which the rabbis, they derived that you should add some time to Shabbat before it.

And then the text begins to talk about things which for the rabbis were de’rabanan, but based on the statements in Isaiah chapter 58 of certain types of talk and discussion of business and things like this that are forbidden. Then the text moves into issues having to do with carrying on Shabbat outside of one’s domain. It’s there, it’s not exactly the same because there are two domains, a thousand and a 2000 cubic. But even so, right?

David Bashevkin:

See the connection, yeah.

Lawrence Schiffman:

… carry in the public domain, which is mentioned in the Book of Jeremiah, so why not? And then from there they go into such things as not having a non-Jew do work for you. They go into issues of pikuach nefesh, saving a life. So, these things are part of the Judaism, apparently, of your average Jew at the time, even if they didn’t necessarily study these texts. And of course, the Torah itself had prohibited the making of fires and harvesting and planting. I said it out of order, planting and harvesting.

But of course those are prominent, for example, in the rabbinic list in the 39 melachot. So, it looks to me like a lot of this stuff was really common and really there. And by the way, we learn from Josephus that the Roman army had to let Jews out of certain activities on Shabbat. So apparently Jews were observing many of these things.

David Bashevkin:

I think one of the areas that has changed the most in terms of our Jewish identity is the role that talmud Torah plays. The study of Torah. I mean, now there’s not a Jew in the world where even the notion of getting a Jewish education is central. I’m curious, if you were to ask a Second Temple period Jew what role the study of Torah plays, what would that even mean to them?

Lawrence Schiffman:

I think that there is one of the big differences between, certainly the Pharisees and the Dead Sea sectarians and your, most of your other Jews. Because the Pharisees and Dead Sea sectarians were very much engaged in study of what we would call generally Torah, because you mean Torah in the wide sense, not just the Torah and the Books of Moses-

David Bashevkin:

Correct.

Lawrence Schiffman:

Now they were very much engaged in that. And on the other hand, for most of the Jews, the center at that time was the Temple, and the various rituals pertaining to and concerning the Temple. And we know that two things happened as a result of the destruction of the Temple. One is the institution of the synagogue developing from what it was basically just its early beginnings into the full-fledged synagogue. And second of all, we know that if you want to speak using a non-Jewish term, the sacraments of Judaism, that when sacrifice ceased to be a sacrament of Judaism, study of Torah along with prayer, those two things were essentially the replacement sacraments.

So we do have to realize that the idea of universal Torah study in a serious way… Now this is despite the fact that we have evidence that already in the first century BCE, education for children was required. But that’s not really what you’re asking about.

David Bashevkin:

Correct.

Lawrence Schiffman:

Education for children is to provide basic literacy, and in terms of Jewish observance, basic ability to function with the prayers and stuff like that. But we’re talking here about really a more advanced education.

I think we need to be aware that the form of mass Torah as a kind of… I don’t know what you want to call it, a mainstay of the culture, which might be jokingly called a substitute for television in the general culture, is actually a modern thing. That’s actually modern. Because we have to remember that in earlier periods, it’s not that others did not participate in Torah study, but they participated in Torah study very much like the impression you get from the poskim that every Jew should do some Torah study.

So this Jew between mincha and maariv in the 17th, 18th century would be a shiur of mishnayot or he would be at a shiur of Ein Yaakov, but he did that every day for a little while. But the idea that every single person should finish Shas and all this kind of stuff, this is, or everybody should be a musmach, this is all modern.

David Bashevkin:

Yes. Let me ask you a little bit, I want to come back to the sects and the way that they interact with one another, and this notion of the common Jew.

Right now, when we look in the present, there is this notion, it’s always frayed, but there is this idea of Jewish unity, that we have to have some underlying connection. I’m curious if the leadership in the Pharisees and the Pharisees and the Essenes and the Sadducees… How did the leadership see one another? Were they hanging up so to speak, pashkevilim and banning one another and saying, “This is the wrong way, we have the right way”? Was there a battle for the hearts and minds of the common man?

Lawrence Schiffman:

Yeah, I think there was a pretty big battle. You read the Dead Sea Scrolls, now admittedly they’re a small minority of the people, but they actually hated all the people that didn’t agree with them. And they said the worst possible things about the people who didn’t agree with them.

Now the Pharisees and Sadducees, so we know that they argued with one another. People who argue with one another, it’s not so bad. And if you take a look in the New Testament and you see the arguments that are pictured there as taking place between Jesus and his followers, and Pharisees or Sadducees, you also get the idea there’s a kind of a norm of argumentation that went on. So apparently these groups, they didn’t agree with one another, but they had no problem talking to each other and disagreeing with one another in those conversations.

You see it in the Mishna, especially in the Mishna Yadayim, between the Pharisees and Sadducees, very similar to what you see with the Christians and the Pharisees and the Christians and the Sadducees in the gospels. So apparently there is a sense of some kind of ability to disagree civilly. Of course, there are one or two examples mentioned in our sources of people getting quite violent about this. There’s one mentioned in the Talmud of a struggle between Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai that one would never imagine turn into a physical struggle. But of course, these things do sometimes happen.

But I don’t think that Jewish unity was spoken about so much. I think it may have been assumed. And the rest of the world, when we read the Greco-Roman sources about the Jews, they’re describing Jews as a very unanimous group, so unified that they regarded them as xenophobic, as hating outsiders. So I think that it’s pretty clear from especially the Greco-Roman sources, the Jews were quite unified-

David Bashevkin:

Just to be clear, those sources are referring… When they talk to the Jews, they’re talking about all the different sects together, the same way-

Lawrence Schiffman:

They don’t know one guy through another one. And on some reason, you have only Hellenistic Jews, Jews who spoke Greek, but to them they’re all the same. Why are they all the same? Because they were, from the point of view of these people, completely unified. You see, I have to tell you something interesting. It’s only Jews who think Jews aren’t unified. Forget about the antisemites, who think that they’re unified to control the world. The reality of the situation is that there takes place of war in Ukraine and the first people that you can see at the border of Poland, the people with signs up, “We’re here to help the Jews.”

Nobody cares which Jews, nobody cares what kind of Jews. And you got 17 Jewish organizations run to these places, they cooperate totally. And the whole Jewish disunity, which you hear about all the time and these sermons you hear about it, don’t really know what disunity is, if you understand what I mean. This is a theme that has become stated over and over and over, but the level of disunity is nothing like what people seem to think.

David Bashevkin:

Tell me a little bit more about the world of the Pharisees and where they emerge from. When you study in, whether it’s in a yeshiva or a seminary, and you open up the way rabbinic texts depict their own history, the first thing that comes to mind is the Mishna in Pirkei Avos, which says Moshe kibel Torah mi’Sinai, Moshe accepted the Torah, he gave it to Joshua, and Joshua gives is to…

And here we are all the way down to Shimon HaTzaddik. It’s come down to us as this unbroken chain. And to me, I think part of the… maybe I would call it the fear of studying Second Temple era history is that the unbrokenness of that chain can feel disrupted. So I’m curious, in the eyes of the Pharisees in this emergent Rabbinic Judaism, did they already feel at that time that they have an unbroken tradition dating back to Moses? Meaning to Moshe?

Lawrence Schiffman:

No. The information that we would have from this is essentially Josephus and a little bit from Philo Judaeus. Now, Josephus speaks about what he calls the unwritten law-

David Bashevkin:

The tradition of the fathers.

Lawrence Schiffman:

Right. He never makes the claim that it came from Sinai. The earliest sources we have making the claim that it came from Sinai are Tannaim, Mishnaic teachers, talking about the Second Temple period before the destruction of the Temple and saying that. Now on the other hand, if we go back to Ezra, Nechemia, andDivrei HaYamim, Ezra, Nehemiah, and the Books of Chronicles… These are books that most Jews have never read. Tell a Christian that most Jews have never read all those books, they can’t believe it. Let alone-

David Bashevkin:

Correct. Quote a Mishna and Pirkei Avos. You’re saying you could go back to before that? Yes.

Lawrence Schiffman:

Now here’s why you have to do this. Because certain aspects of what we call Rabbinic Judaism are already in these books. Now just as a small example, public Torah study is in Ezra. Public Torah reading is in Nechemia. Now forgetting the halachic stuff that’s also in Ezra and Nechemia, all kinds of very interesting things. But what I want to point out is that the idea of using midrash, one verse being explained by another verse, as a technique to create the law and understand the law is already in Ezra, Nechemia, and Divrei HaYamim.

Just one famous example from Divrei HaYamim is, how do you deal with the fact that the Torah says Shemotthat you’re supposed to roast your korban Pesach, and that you may not cook or boil your korban Pesach? And in Devarim it says that you should boil your korban Pesach, and comes along the Divrei HaYamim and says “No, the roasted one is the korban Pesach and the boiled one is the chagigah, the festival sacrifice.”

Now, this is the type of thing that we see in the midrashei halacha later on. So when you study this, and also if you study the sectarian material that we have from Second Temple times, you can see that the notion that the rabbis or their predecessors would have already been engaged in midrash and in these forms of interpretation is already there.

For example, there’s a Dead Sea Scrolls text that’s speaking about the Pharisees, says asher b’Talmud shikram that “in their Talmud is their lie.” Now what they’re saying here is that there already is the method of Talmud, not the book the Talmud-

David Bashevkin:

Correct.

Lawrence Schiffman:

… method of analysis, as Rashi explains it, to derive one thing from another thing. Lehotzi dava m’toch davar. That’s how he defines the word Talmud. Now he’s really defining, in your Gemara he’s defining the the word Gemara because you have a censored Gemara. But in the manuscripts, he’s defining the word Talmud, and he says it’s to learn one thing from another. So the point is that we can learn both from the rabbinic texts speaking about the earlier period, and from a variety of other Second Temple texts, which say things sometimes from a negative point of view about the Pharisees, that they already were doing a lot of these things that typify the rabbinic tradition in the Second Temple period.

This, by the way, was a big point missed in Jacob Neusner’s whole re-reconstruction of the Rabbinic period. Forget about the particulars of it, he basically ignored the Second Temple period, so it looked like everything was created after 70. And it wasn’t created after 70. Much of these things are already there in the Second Temple period. And this you can see. Let me throw out an example just out of nowhere, I mentioned before about the question of pikuach nefesh–

David Bashevkin:

Saving a life on Shabbos, to save another life, yeah.

Lawrence Schiffman:

Now it’s well known that the early Christians… And the New Testament pictures Jesus as feeding hungry people on Shabbos. Now what people don’t realize is that in a confrontation with the Pharisees that’s pictured also in the gospels, he says to the Pharisees, “But don’t you do korbanot on Shabbos? Don’t you sacrifice and burn offerings on the Sabbath?” What’s he saying there? He’s saying, “You guys agree that a positive commandment can push off a negative commandment. So I’m telling you that the positive commandment to feed the hungry allows us to pick grain and do it on Shabbos.”

Now, we don’t accept that argument for a very simple reason, because a hungry person can wait a couple hours till Shabbat is over. He’s not dying or in some kind of difficult sickness where we need to help him. So okay, we don’t accept this argument. But look at his argument says about the Pharisees. He says to Perushimnot simply that you believe in pikuach nefesh, but you believe that positive commandments push off negative commandments. Now we would not have known, if not for this passage, that that principle existed in Second Temple times, and here you see the principle right there in Second Temple times.

David Bashevkin:

Of “aseh docheh lo sa’asei” and trying to use that to justify-

Lawrence Schiffman:

Yes. Yes, and that’s a pretty subtle point. Now this is not the place for this discussion, but it’s a reality that the New Testament is an excellent source for things about the history of the Jews, right? There’s some funny aspects of it.

David Bashevkin:

Correct.

Lawrence Schiffman:

It’s true. Do you know the first Jew that we know was called to Haftorah? Not that he invented the Haftorah. The first Jew to called to Haftorah is Jesus.

David Bashevkin:

He’s the first Jew that we have recorded being called-

Lawrence Schiffman:

That we know as a fact was called to the Maftir, read a Maftir the first one who read a Maftir. And we know that he read a Maftir. Now the point is, there’s a funnier one.

David Bashevkin:

He didn’t get shlishi though, so.

Lawrence Schiffman:

We name the baby at the bris.

David Bashevkin:

Yes.

Lawrence Schiffman:

Who was the first person in the world that we know as a fact was named at his bris? John the Baptist. It’s crazy, but it’s true. So there’s a lot of historical sourced material there.

So the point I want to make here, though, is that there you see that he even knows, or his followers who wrote it, it doesn’t matter, know, that this principle exists in Jewish law in Second Temple times, that this principle already existed.

So the point is that there’s a tremendous amount when we trace these sources and the polemics against the Perushim. And we haven’t even mentioned here so far, the very important MMT text as it’s called, Miktzat Ma’ase ha-Torah, which is a Dead Sea Scrolls text, when they argue against pharisaic halachot, and the thing was probably written in like 150 BCE, and they’re arguing against pharisaic halachot that we know from rabbinic text from later on… And you can see that these things existed way earlier in Second Temple times. But the point that we have to realize, it still hadn’t spread in total to the average Jew the way we start to see later on.

But so many things in the Mishna… We have to be careful. Many things in the Mishna are laws that were developed after destruction, but many things were there before. And these Second Temple texts, when we take them all together, show us that.

David Bashevkin:

Can you give me an example from that MMT text?

Lawrence Schiffman:

Yes. I’ll give you the most famous example of the MMT text, because everybody talks about it. There is a debate in the Mishna Yadayim at the end of the last perek about, what happens if you are pouring a liquid from a pure vessel into an impure vessel? The question is, as I pour this liquid from the pure vessel into the impure vessel, does the impurity go back up and make impure the pure vessel on the top?

Now, this debate of the Pharisees and Sadducees in the Mishna Yadayim, the Pharisees say no, impurity cannot go up in the opposite direction of the flow of the liquid. There is a text in this MMT Miktzat Ma’ase ha-Torah, which means some laws of the Torah. In it, there is a direct text saying, “You say…” And what’s the “You say”? “You say,” the Pharisee position. Don’t mention the Pharisees here, but. “You say that it doesn’t render it impure, but we say it does.”

Who are the “we”? The Dead Sea sectarians here agree with the Sadducees, because they basically follow Sadducee-like law. But that’s not our point right now. Our point right now is, look at this. It proves to us that the view of the Perushim existed at this time.

I’ll just mention in parenthesis, it’s interesting that for kashrut… This is not the ruling. For kashrut, the item can flow up.

David Bashevkin:

Yes.

Lawrence Schiffman:

So if you’re pouring from a chicken soup into a pot of boiling milk, the remaining soup in the pot on the top becomes not kosher. It’s different than the purity laws.

David Bashevkin:

That’s actually a great segue, because any time I have these discussions, I feel like I’m talking to two different people. I feel like I’m talking to Professor Schiffman, the scholar of the Second Temple period, and I feel like I’m talking to Professor Schiffman, the Jew. The individual Jew. And I’m looking at you. I see you’re wearing a yarmulke, I can see sefarim in the background. And I’m curious, after spending a career immersed in the Second Temple period, why does your Judaism look the way that it does?

Now, I’m not asking you, you know, the Gemara and Rav Kahana that I’m going to hide under your bed, Torah hi v’lilmod ani tzarich to find out all of the details of your inner religious life. But you present as a committed and observant Jew. I’m not going to ascribe even a denomination to it, that is how you present. Yet you spent your time immersed in a Second Temple period where you know the common Jew of that period, much of the Judaism we practice today, I think it’s fair to say, would be foreign to them. Maybe not all of it, but certainly the details.

Lawrence Schiffman:

A lot of it would be foreign to somebody from a hundred and fifty years ago.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, you would come into an Orthodox home, and they would see you, I don’t know, see the way I make tea on Shabbos. They would see the way that, I don’t know, I’m careful about certain of these details and the way that the halacha governs our life. And in this pre-Temple Judaism, they probably knew about Shabbos, a common Jew you mentioned. They knew about kashrus. But just to get into the kashrus period, the entire kashrus process, I think it would be otherworldly for them.

So my question is, why are you committed to the Judaism that you have? Why don’t you try to whittle down your commitment and observance to go back to what you know to be historically true?

Lawrence Schiffman:

Yeah, you’re asking, and I know you know better, but the naive question, right? “Well, why don’t we do what they did thousands of years ago? Why don’t we do biblical Judaism, right? And try to…” Okay.

The irony of this is that the more you learn about the past and how different the past was, the more you understand actually the power of the system which keeps developing. So in other words, for those for whom historical change becomes an obstacle to observance and commitment, et cetera… For most of the academic type scholars, historical change is the opposite. It’s a sign that the whole thing is relevant in each and every time, because it’s developing in accord with a certain type of semi-teleological, but not totally, form.

So this gets into the question of how you see development. Is development good or bad? You see development as bad, so you’re going to completely deny it and act like everything has always been the same. If you see development as good, then you see no problem that Judaism is expressed in different times in certain different ways and continues to develop.

So just a simple example from right now, something we mentioned before. Look, because of the high levels that exist today of education in general and the society in which we live, and because of issues pertaining to how people entertain themselves and the existence of leisure time, which is actually… in the quantities we have today, is new, right? Not that there was no leisure time.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Lawrence Schiffman:

Just recently there was a discovery of a massive number of bones that are used playing games. People played games in antiquity. It’s not that no one had leisure time. I remember somebody having a shock to realize that some people had lunch at other people’s houses on Shabbat in antiquity, right? It’s not just in modern times that people invite their friends to the house.

But the point I want to make is that if you understand these developments, as in the examples I gave right now, let’s say in modern times, you see in very short time how developments are positive, not negative. And just an example of this is the translation of traditional text into the vernacular. At the beginning this was regarded as negative. When Lazarus Goldschmidt translated the Talmud into German, he first was promised a haskama from Rav Elchanan Spektor, Rav Yitzhak Elchanan Spektor, and then he took it back and said, “No, I won’t give it to you.”

And forget the details for a minute because they’ll take us too far off our topic. The reality of the situation is, today every big gadol under the sun is signing on to translating texts into all kinds of languages. Forget English, French and Spanish and Russian, and we’ll see Ukrainian before you know it.

David Bashevkin:

But allow me to push a little bit further, because the question that I get from so many of our listeners is, maybe it’s a question more about rabbinic authority, but you’re saying if this is not how it always was, then how do we even know that this is what God wanted? Meaning, what should animate our contemporary commitment? If it doesn’t link back to something clearly divine from very… Moshe kibel Torah mi’Sinai, he got this Torah, the oral law as we know it today goes back sequentially, then how do you justify your commitment to those aspects that don’t go all the way back?

Lawrence Schiffman:

Let’s understand something. The difference between the written Torah and the oral Torah is that the written Torah is a thing which is almost completely, from our point of view, divine. Now we say almost completely. It’s not completely, because being passed on by humans… and there’s all kinds of evidence to this change of the script and this, that and the other thing.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Lawrence Schiffman:

Okay? So I don’t know what we want to say, 95%. Whatever percent we’ll decide doesn’t matter. But the whole idea of the oral Torah, and this emerges from reading the Rambam’s hakdama to the Mishna, but ironically he says some different things when talking about it in the Mishna Torah. But one could see here that it’s a divine-human partnership. So it’s a divine-human partnership, so there’s this kind of divine origin, and then there’s some kind of indirect divine help, we hope. But there’s an ongoing process of humans, and the ongoing process of humans never stopped and isn’t supposed to stop, and it’s supposed to continue developing.

Now if you don’t like that concept, you won’t really want to know about the past, because you’ll have this problem all the time. You’ll have to face that people didn’t wear long black coats, or certainly short jackets, black suits, in whatever. They didn’t even wear black hats until 200 years ago. In fact, producing the color black is hard to produce, in case-

David Bashevkin:

The very color is modern.

Lawrence Schiffman:

It’s hard to produce because it’s effectively the absence of color. It’s very hard to produce.

I mean, that’s obviously an unimportant example. We heard all these examples all the time of silly things, like how big was the Chafetz Chaim‘s kiddush cup? Silly things. But we start to talk about the things that really matter. It’s quite clear that this idea of a divine-human partnership is what makes it go and what keeps it going. And that observation is sort of also a version of the Sefer HaIkkarim, Rav Yosef Albo.

But the point I’m making is, there really in a certain sense today are two different ways of doing it. You can acknowledge history and see a continuity behind that history, and therefore feel that our obligations are to do this the way it should be done today. And then the other possibility is to deny history and act like there is no history, and there are people who are walking around that way, but it’s quite a naive point of view because it doesn’t appear to be true.

But okay, I don’t make it my business to go around telling people what they should or should not believe, and certainly not going to people who have more simple beliefs and trying to convince them that they should take a historical approach. But the reality is that there are, you might say, these two ways of looking at it.

Now, I think that probably the way I’m explaining it is the way most historical type scholars would explain it. I think that that’s basically the case. Now, I just want to point out that there’s a sort of a reverse thing that one has to also remember. Just a couple of weeks ago, I was in Israel, and I was visiting a lot of archeological sites, and I visited a synagogue called Ein Keshatot in the Golan. Now this is a synagogue building that’s standing to an unbelievable extent after its restoration. They used a computer system to restore all kinds of… really, they figured out where all the pieces went. So you’re really in the whole building. You’re not just in some broken ruins. And you’ve got the aron kodesh that’s shaped with that whole tablature, like many of them until today. The point I’m making is that here you see the opposite, the continuity.

And for example, there are over 850 mikvaot out that have been found in Eretz Yisrael. You see the continuity. So you shouldn’t picture this, that there is simply a discontinuity of history. There’s a continuity of history, which runs through a lot of things. I just gave a few small examples here, but one could give many other examples of that. Even if it’s true that there’s also aspects which are not continuous, or aspects where something is being built on something which is being built on something which is being built on something which is being built on something.

David Bashevkin:

Let me ask you, you said you’re not in the business of telling people what to do, but I am curious. You are a teacher at NYU. Surely you have had both Jewish and non-Jewish students. And I’m sure people have come to your classes over the years, you’ve been teaching for decades, and somebody sits in your class, maybe it’s a Jewish student, maybe it is a non-Jewish student, and they want to know, “Wow, there’s really like, religious has been animating world history. I want to make a choice about this in my own life. I want to be a part of this unfolding story. How should I approach this in my own life?”

I’m curious if that has ever happened, and what advice, how do you approach that as a professor? You could say, I don’t know, “Read my book, enjoy.” Or how do you approach somebody who’s like, “What should I make of this now?”

Lawrence Schiffman:

I tell you something very interesting, it almost never happens. And the reason it doesn’t happen is because the students understand the difference between what we do and what they do at the Bronfman Center for Jewish Student Life and Chabad at NYU. They understand that those are where you go to take the two and somehow figure it out. So generally, actually that doesn’t happen.

David Bashevkin:

I’m actually shocked that it doesn’t happen more. If I sat in your class-

Lawrence Schiffman:

Almost not at all. Look, first of all, also, my program of what I currently teach doesn’t make that too likely. But leave that aside. In the past I taught things that made it much more likely.

And I think that the students understand that what they’re getting in the academic approach is an attempt to reconstruct what really was and what it means, in terms of what it wants to convey and what it means, et cetera, et cetera. And then the next question, “What do I do,” I think were questions that they took elsewhere and not to us. And I think that somehow, they understand that more than you might think. It’s very rare. I could tell crazy stories, but they’re not really what you want.

David Bashevkin:

Do you think that’s a good thing? Do you think that the work of Second Temple historians should play a bigger role in our discourse and the way we reflect on contemporary Jewish life?

Lawrence Schiffman:

Well, I think you have to go back to an earlier question, because the earlier question is, when you teach academic courses in the university, do you want to be the one that people come to with those issues, when in reality this creates a situation where your relationship to all the students in the class is not the same? So it creates a class, for example, in which non-Jews might not feel at home. And various disadvantages to Judaic studies in a university begin to happen if these things are not kept separate.

And this is despite the fact that over the years, I’ve spoken many times at the Bronfman Center, I’ve spoken for Chabad at NYU. But that’s a different story, because in the classroom, you want to make sure that your class is seen like the chemistry class. The student goes to learn chemistry, he does not ask the professor to alter his chemical status.

And I know that’s a silly type of example, but it’s I think an important point. And we need to do our job, and the maintenance of the difference between that job and the other job is important to Judaic studies being a recognized academic subject. So it doesn’t really happen. They usually know better.

Now another thing, just one subheading of what you’re talking about now, is we use a certain type of discourse which removes us from the discussion. So it’s not, “We do this,” but “Jewish law requires that someone do this.” Now I can stand up in the class and describe the laws of niddah as understood in the Mishna and Gemara with no problem at all, because no one’s going to raise his hand and start discussing whether it’s a good idea or not. We’re understanding what the beliefs are in these texts, right? So it doesn’t stop you from discussing any topic, but you’re not opening the types of discussions of, how would it apply today?

David Bashevkin:

Let’s say not people in your classroom, but your book is widely read, people email you. When you get an email and somebody appeals to you to help them figure out… and you know, I’m staring right now, I’m showing you, we’re not going to release this. This is a four-page email that I received from a listener. Every one of these questions is on your book, every single one, because they knew I was interviewing you and they were so excited and-

Lawrence Schiffman:

Hey, we have time for all those-

David Bashevkin:

We don’t, of course.

Lawrence Schiffman:

The answer to this is, I do answer those questions, and very often the questions I get, however, are… from people when it’s questions of faith issues, they sometimes are far out. I do answer those questions. Often I tell the people to talk on the phone, right? Because it’s much easier, because you can understand better what their issues are that really are the issues for them.

And sometimes those issues are that they are people who can’t accept a historical type of approach. Now I know I had an experience once, I went to speak at a Chabad in California somewhere, there was a rabbi there, and he’s asking me, “Can you prove this? Can you prove this? Can you prove this?” And I explained to him at great length something he never really had thought about, that much of the idea of emunah is that we can’t prove it.

So there’s a lot of stuff that we believe that can’t be proven, and to try and prove these things and believe there is a proof, and that’s where some of this comes off. Because people are looking for proofs of things that can’t be proven. And probably the value that we gain by believing in these things might not be there if they were proven, because we don’t get, let’s say, ethical and personal value by believing in scientific facts.

I know by the way that’s maybe not true, because people don’t believe in scientific facts of dying of corona. So maybe what I’m saying is really not true. Maybe we do gain by believing in scientific facts. But at any rate, I used to believe that believing in scientific facts is just believing in simple things that we know are true, as opposed to believing in things that we’re committed to, which we can’t prove.

David Bashevkin:

What’s something we can’t prove? Give me an example. Obviously let’s leave off the table, God…

Lawrence Schiffman:

Oh, we can’t prove where the Torah came from. We have no proof that God had anything to do with the Torah. We can’t prove it. It just says that. So if you believe that the Torah is divinely inspired, that’s an unprovable belief. If somebody thinks that some historian should be able to prove this fact, you can’t prove this fact, which is why some people think the opposite.

David Bashevkin:

Can it be disproven?

Lawrence Schiffman:

I don’t think it can be disproven. There are people who think they can disprove it, because the reason that they think they can disprove it is because what they’ve disproven is that it would be written by one human. As disproven… It’s too complicated. But they’re using a simplistic approach of what would divine inspiration be, and then on top of the simplistic approach of divine inspiration, they’re then trying to disprove it as if it was human. But if it’s not human, you can’t disprove it with the same criteria.

But the point I’m making here is that when many times people write me, they want to proof of something from antiquity. And I don’t have a proof of these things that they want from antiquity, right?

David Bashevkin:

Correct.

Lawrence Schiffman:

Let alone various details in the accounts that we see in our literature. I mean, can you prove that Rebbi Akiva was martyred by the Romans? Now it depends on what you mean by prove. If you accept the various Jewish texts as saying so, okay, but if you want some other proof, we don’t have one. Nothing you can do about it. There was no CNN or New York Times in those days.

David Bashevkin:

Correct.

Lawrence Schiffman:

We don’t have the type of information. I get a lot of that. People who want proofs for things that can’t be proven.

David Bashevkin:

Gotcha.

I’m curious about you, how your faith, how your commitment and observance has changed. You’ve spent your life immersed in Second Temple Judaism, you’ve spent your life immersed in a very different world than the one you have been born into, and that has evolved since being born. You grew up almost nearly to the year as my father. A lot has changed in the Jewish world since that time.

Lawrence Schiffman:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

I’m curious how, on a personal level, your scholarship has impacted your observance and your commitments.

Lawrence Schiffman:

Well see, I’ll tell you what’s very funny. Because remember, besides studying Second Temple times, I almost do a lot of work in rabbinic period. I actually have a volume that’s almost ready for press, which is over 40 articles re-edited that I wrote on non-Dead Sea Scrolls, and most of it’s not Second Temple.

David Bashevkin:

When’s that coming out? Maybe you could tell our listeners.

Lawrence Schiffman:

Well, it’s going to be a book coming out, I assume, from Brill publishers. It’s going to be very expensive.

David Bashevkin:

Oh yeah, we know about Brill publishers. Our listeners know.

Lawrence Schiffman:

It’ll probably be about two years.

David Bashevkin:

Okay, two years. So start saving up now, because…

Lawrence Schiffman:

Yeah, it’ll be about two years.

But at any rate, the point I want to make is that I spend an enormous amount of time studying what at least is academically termed rabbinic literature. Right? Which includes Bavli, Yerushalmi, midrashim whatever. This coming semester I’m teaching a course on the midrashei halacha, as an example. So the point is, I spend a tremendous amount studying that.

So it’s not really totally true that there’s a complete divide between the Second Temple material and the later material. And one of the big things that I’ve tried to show is the extent of similarity and continuity in these things, as opposed to the people who saw them as absolutely discontinuous. So I would say ironically that if anything, of course as I think that’s the case with most people, the more you get in and understand better the details of the system, the more careful, hopefully, you are in doing the system correctly.

But I would say that that’s really in a certain sense the main way, and as you go through life, you may take on this or that custom or follow this or that thing that you read about and this or that book. But I think other than that, there’s probably no real much of an effect.

David Bashevkin:

I’m curious about the disappearance of the Essenes and the Sadducees, and I’m curious if they were self-conscious of their own demise. Meaning, we hear so much nowadays with hand wringing every time a Pew report comes out and every denomination is comparing themselves and who’s growing and who’s shrinking, and there’s a lot of hand wringing. I’m curious of that anxiety, that notion that a major sect within Judaism can disappear. Did it happen in one fell swoop because of the destruction?

Lawrence Schiffman:

Yeah, I don’t think you have such a thing, because I think they were confronted by an overturning of reality through the destruction that they didn’t really see coming and didn’t expect. That’s my guess. Ironically, the people who do the most hand wringing over the destruction that we have… Because what’s preserved is chazal, the Rabbis. We don’t know what the Sadducees said when the Temple was destroyed.

Now, we do know that some Sadducees traditions went underground and emerged in Karaism.

David Bashevkin:

Yes.

Lawrence Schiffman:

We also do know that in rabbinic literature, you have references to some leftover sectarians and stuff like that. But we don’t know how they understood what had happened, how they understood why they now are on the fringes of a group that’s basically following rabbinic tradition now with the Mishna, and then later the Gemaras.

David Bashevkin:

And if somebody were to ask you, “Professor Schiffman,” I’m posing this question. “Why are you not a Karaite?” Both the Sadducees and the Pharisees, they both date back… I don’t know if we, as you said, definitively know which one came first. They both have very old traditions. Yeah. So why not be a Karaite in 2022?”

Lawrence Schiffman:

Well, because the problem of Karaism is exactly the problem that all of the theologians describing the whole rabbinic system talked about. That if you try to follow the Torah alone, you have a rigidity which is impossible in maintaining a continuity, which is why there are almost no Karaites left. They’re more than people know. They’re like 30,000 in Israel. There are even some in the United States, people might not know that.

But the problem of Karaism is, it faces the constant challenge that it lacks a system to allow it to adapt to new circumstances. And this, as the Sefer HaIkkarim of Rav Yosef Albo says, this is the big advantage of the pharisaic system, or as the academics call it, pharisaic rabbinic system, because it makes it possible to adjust, and adjustment doesn’t take only one direction. Because in modern times today with the other Jewish movements, one assumes adjustment means to become more lenient. It doesn’t mean to become more lenient. It can also mean to become stricter, depending on what the issue is. So when we see the adaptation to circumstances, the problem of Karaism is that in certain ways it’s a dead end system.

Now it’s true that they had to adapt it anyhow. Once you get into the Middle Ages, the Karaites start early… or middle Middle Ages. They start adapting their own thing, partly taking on rabbinic views and partly softening things. Well, but the bottom line is, it’s so rigid and it’s so literalist that it can’t survive and can’t work. So what you’re doing becoming a Karaite is to deny the genius of chazal, of creating this ongoing system of a tradition that can keep going. You want to do that, you’re really burying Judaism.

David Bashevkin:

It’s really phenomenal, and it’s the response in so many ways when I have this discussion, there’s so many friends that I have it with. When you’re so tethered to the canonical prophetic books, you’re stronger in a way, but you’re also more brittle. You don’t have that resilience and dexterity. When you become less tethered and you have this grand edifice of a rabbinic tradition anchored in the perpetual interpretation of the Jewish community, you may not feel as strong because it’s not directly from the word of God, so to speak, but the collective tradition has a resilience that has allowed it to be perpetuated for the 2000 or so years since that destruction.

I cannot thank you enough. This has really been absolutely enlightening. I always wrap up my interviews with more rapid-fire questions, and I was wondering if you would indulge me. My first question is, aside from your own book of course, I’m going to mention you have many. From Text to Tradition: A History of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism. For somebody who wants an introduction to this world, what has changed? What book would you recommend? Unless you just say, “It’s mine.” I mean, you really did write the book on this.

Lawrence Schiffman:

I’m going to say it’s mine, but I’m also going to say that just a week ago, I discussed with the publisher about a second edition. So I’m hoping it’ll come out. Unfortunately, I don’t know whether there’s another book that’ll solve that person’s problem. I’m not sure. But I will also say that there’s a book of texts called Texts and Traditions that accompanies it for students, use it in a lot of classes. People could find the primary sources there, so they don’t just have to take on faith what I wrote.