Liel Leibovitz and Lisa Ann Sandell: When A Spouse Finds Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Liel Leibovitz and Lisa Ann Sandell about what happens when one partner wants to increase their religious practice.

Summary

This series is sponsored by our friends Sarala and Danny Turkel.

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Liel Leibovitz and Lisa Ann Sandell about what happens when one partner wants to increase their religious practice.

Liel grew up a secular Israeli, while Lisa was raised in a traditional home of loosening observance. When, eight years ago, Liel brought up the idea of keeping kosher, they realized they were moving in different directions.

- What first drew Liel toward growing religiosity?

- How did Lisa react to the changes in Liel’s worldview and lifestyle?

- How are they able to run a home, marriage, and family together despite being on separate and dynamic paths?

Tune in to hear a conversation about being a “helpmate,” someone who both challenges and uplifts their spouse.

Interview begins at 11:21.

Lisa Ann Sandell is the author of the young-adult books The Weight of the Sky, Song of the Sparrow, and A Map of the Known World.

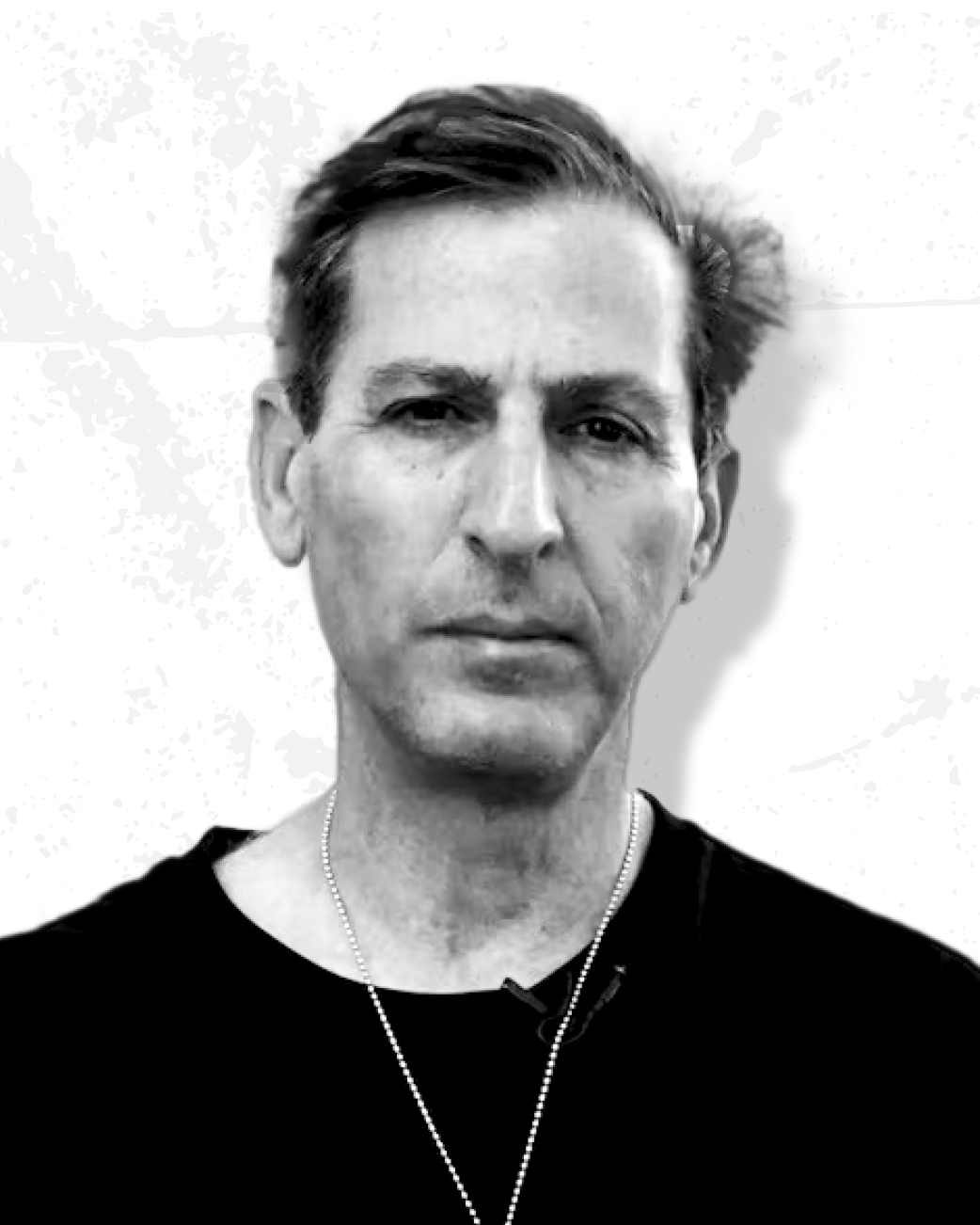

Liel Leibovitz is editor at large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One.

References:

“Eli, the Fanatic” by Philip Roth

Sin•a•gogue: Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought by David Bashevkin

Daniel Deronda by George Eliot

How the Talmud Can Change Your Life: Surprisingly Modern Advice from a Very Old Book by Liel Leibovitz

“Everlasting Love” by Rabbi Shlomo & Eitan Katz

Transcript

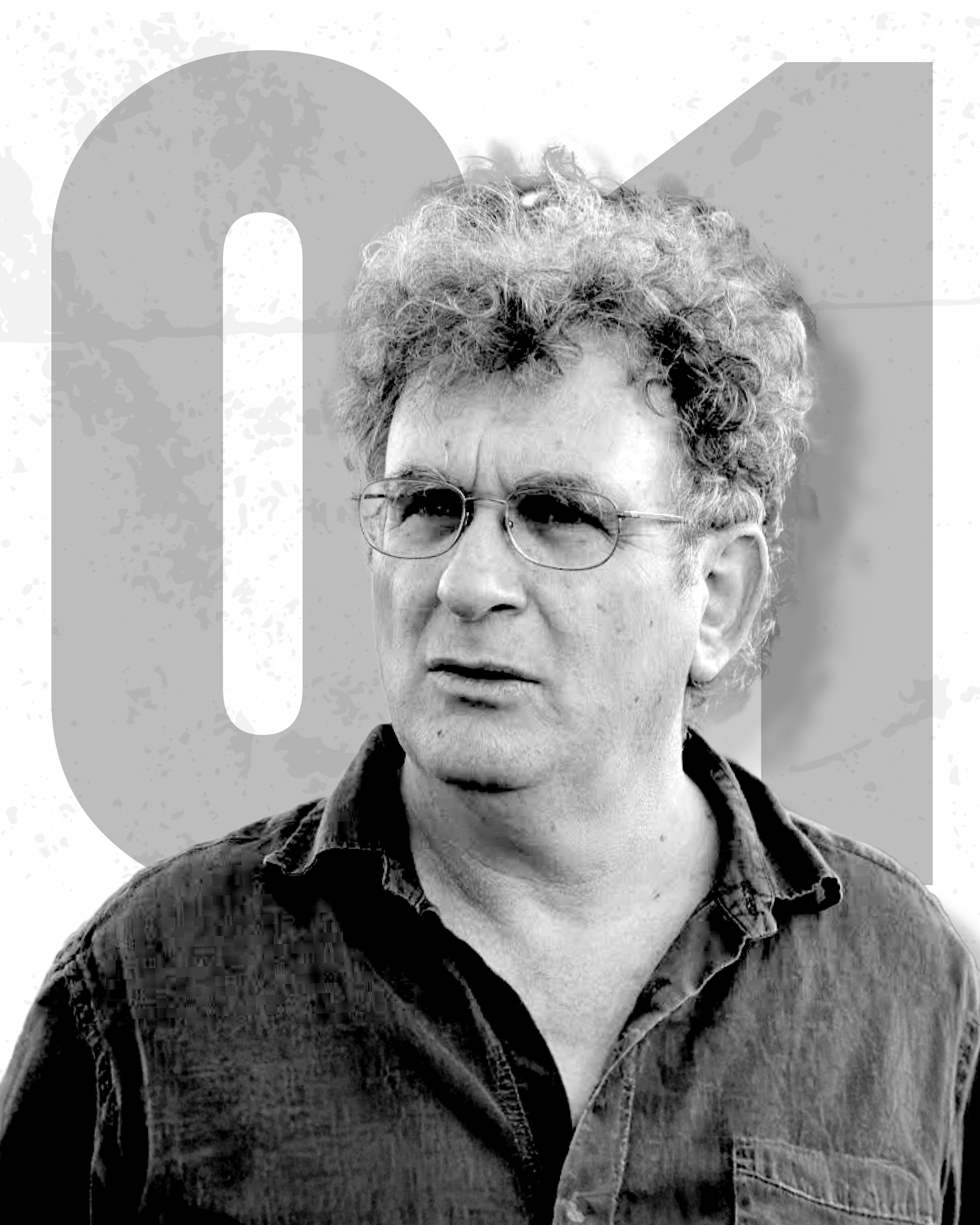

David Bashevkin:

Hello and welcome to the 1840 Podcast where each month we explore different topic balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host, David Bashevkin, and this month we’re exploring intergenerational divergence. Thank you so much to our generous sponsors, Danny and his incredible wife, Sarala Terkel, for their sponsorship once again of this series. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big juicy Jewish ideas. So be sure to check out 18forty.org, 1-8-F-O-R-T-Y.org where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings and weekly emails.

There was a fascinating exchange on a Daf Yomi broadcast. There’s an incredible Daf Yomi, I think it’s called The Eight Minute Daf by Rav Eli Stefansky. I’m not a regular listener but I really enjoy the way that he cultivates community with his audience. I think it’s absolutely incredible. He does incredible work and he really invigorates people if you’re looking for a Daf podcast. Yeah, I’m sure most of our listeners who do Daf Yomi have already heard of him, absolutely wonderful. But there was a brief exchange. He does something similar that we do on 18forty. He reads a lot of emails. I don’t think he has a voicemail, but he does read a lot of emails and they’re always fascinating. And he one time read the following email:

Rav Eli Stefansky:

Last week was a really rough week at home and during a tough moment between my wife and I, she said, “You care more about the Daf than me.” I haven’t been able to watch this year since. It’s funny, but it’s not funny because I spoke to some people and a few people have this issue so I want to address it, actually. “And I don’t know what to do,” he says, “how could it be that Daf Yomi is a source of a shalom bayis issue? I’m at a loss. I can’t believe that my learning Daf could lead to such a negative feeling in her, but I don’t want to cause her pain. What am I doing wrong? Any advice? We really appreciate it, shkoyach and gut voch, Mr. Anonymous.”

The most I could tell you, she’s right. The wife has to feel that she’s number one. She’s number one. You also have to explain to her that hard that the schar that you have in this world and in olam haba is split equally and she’s a part of it.

Another thing you can explain to her is, like everybody else knows and says, it’s that the Daf will make you a better husband. So it’s to her benefit that you do the Daf.

David Bashevkin:

I froze when I heard that because I don’t think there is a home in the entire world, I don’t think there is a Jewish home in the entire world, where some permutation of that sentiment has been said. I’m not talking, of course, just about Daf Yomi but the sense that, “I feel like I am no longer the number one priority. I feel like you are more committed, more loyal, more passionate about some religious commitment than you are to me, your spouse.” And it’s not always a major earth shaking, earth shattering issue. Could sometimes be very small. It could be somebody who wants more help maybe in the early morning with kids and the one spouse wants to go to minyan. It could be about difficulties related to Shabbat observance, difficulties related to attendance in shul. It could be a host of things. For some families, I grew up with some permutation of this, it could be adherence to the eiruv which can be very difficult for young couples who are careful about, who maybe don’t use the eiruv of in a certain area, the partitions that allow one to carry on Shabbat which would prevent somebody from pushing a stroller on Shabbat for instance.

There are many ways, and I think there is not a Jewish home in the entire world that’s some sentiment of, “You care more about X,” and X is some religious obligation, “than you do to me.” I look at that as, number one, thank God at least they’re speaking to each other. At least they’re talking it out. I don’t know what this couple said to one another, but I think the sentiment is so real and it’s such a real part of the way our religious obligations interact with our familial connections.

And obviously it’s not just with spouses. I think it’s almost spoken about less with spouses. I think we’ve begun to talk about this more when it comes to children, that religious commitment should not erode the relationship that you have with parents. I know my mentor, Rav Moshe Benovitz, I don’t want to misquote him but I believe he tells his students before they go back to America… He teaches in an Israel yeshiva and I believe he always tells his students that if you come home and the way you treat your parents, the way you talk to your parents, your relationship to your parents is not materially enhanced, is not obviously enhanced by your year studying in yeshiva, then you have done something wrong. The way that you transform after a year studying in yeshiva can’t just be with your relationship with Torah, it can’t just be with your relationship with Shabbat or with davening. It has to bear upon the way that you treat your own family. It can’t even mean the way that you do chessed out in the world or the way you give tzedaka.

I think sometimes the hardest chessed, the hardest kindness, are the ones that are expected, are the ones that are almost taken for granted, should be taken for granted, and that’s the family. And you come home after a year studying in Israel and the way that you talk to your parents, the way that you relate to your parents. If that is not transformed, then forget about what that says in an essential way about your religious development. But just the optics, and I don’t think he was coming from the place of optics, but just looking at the optics, it is not a good sign and can lead to a very obvious chillul hashem, a desecration of God’s name.

“This is what you come home with? This is the way you talk to me after a year studying in yeshiva?” I remember my roommate when I was in Yeshiva. He lamented the fact to me that when he actually came back to yeshiva, his mother asked him to make him a cup of tea and he started hemming and hawing because the way that they were able to make tea on Shabbat specifically wasn’t the ideal way of the way you would make tea on Shabbat, and he ended up politely declining and saying, “I’m sorry, I can’t make you that tea.” And he lamented to me. While we were still in yeshiva, he said that, “I didn’t handle that correctly. I didn’t handle that the right way.” Which doesn’t of course mean that you should violate your religious principles just because a parent tells you to do something. Obviously that’s not what we’re advocating, but the way that we negotiate that relationship needs to be enhanced. Our religious ideals need to carry over, need to transform our familiar relationships.

And obviously, maybe not obviously, that needs to be the case in our spousal relationships. And sometimes very often, and I think this is even more common when one spouse becomes very maybe more passionate later in life and awakening, and I see this all the time in the community I grew up in, somebody wakes up and is looking for more meaning, more purpose, and finds it in Torah learning and commitment. One of the spouses can look and say, “What happened to me? How is this going to affect our relationship? How’s this going to affect the way that we vacation together, the way that we connect to one another? Are your religious ideals going to translate into the care, into the love that you have for me?” Or, God forbid, someone could be left wondering, “Ever since X, ever since davening, ever since Shabbat, ever since learning Torah, it seems like you don’t care about me.” God forbid. And we can be left with those questions.

That’s why I think it was so important to explore this topic. It’s not technically intergenerational divergence. It’s intra-generational divergence about how spouses negotiate religious change, religious difference within a marriage. There are so many different permutations of this. We have one example in one conversation, but I think in a larger sense, any one conversation can be a window to what happens in ways big and small within all of our relationships and with all of our marriages. And it reminds me in many ways, there’s this beautiful story which Tzvi Alperowitz shared with me about the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Tzvi Alperowitz as the rabbi of the Chabad in Martha’s Vineyard. He shared with me this absolutely beautiful story where a Chabad chassid I believe his name was Rav Ruving Dunning, he got married and he asked the rabbi to, so to speak, be the baal habayis of his new home. “We want to run the home according to your standards, Rabbi.” And the Rebbe agreed, but he had a condition: on the condition that the behavior inside your home will satisfy my ideals and my concern. And the rabbi clarifies, says, “What I mean… What does it mean, ‘my ideals?’ What I mean is that there has to be shalom bayis, there has to be peacefulness, serenity, kindness within the home.”

A lot of times when a rabbi tells you, “It has to satisfy my ideals,” you would assume he’s talking about the level of Torah learning, the level of piety, tznius, your yiras shamayim, the amount of charity given. But no, the rabbi said, “When I say ‘my standards and my ideals of how you run a home,” I’m talking about one thing: I’m talking about shalom bayis. How do you treat one another? What is the peacefulness in the home with one another?” And the rabbi in many ways modeled this. He once said it’s really, really remarkable where the rabbi used to have private tea time with his rebbetzin, and the rabbi one time said that he equated the importance of the tea time he had with his rebbetzin, with his wife, on a daily basis with the obligation to put on tefillin every morning, that “I need this, I need this in order to get through the day, to be able to talk to my wife with kindness, with connection, with closeness.” This to him was on par with putting on tefillin. It was a religious obligation.

I think that there’s a sweetness to that, an understanding that our religious ideals need to inform, need to elevate, need to transform our familial relationships. And I think in other ways our familial relationships can transform and enhance our religious obligations. And this dialogue where they’re not cordoned off in separate rooms can avoid a lot of the heartbreak and heartache that’s so often happens when one couple feels or maybe even articulates, “I’m no longer priority number one. I’m worried that ever since you stopped caring about me.”

I think today’s conversation, which I’m so excited to share with my absolute dearest friend, I’ve been working with him on a Daf Yomi podcast of our own. If you’ve never heard, it’s called Take One. It is the Daf Yomi podcast of Tablet Magazine. And my dearest friend Liel Leibovitz reached out to me. It was the day before the siyum hashas and he reached out to me and he said, “David…” We didn’t know each other so well. He reviewed my book Synagogue for Tablet. He says, “David, I want to do a Daf Yomi podcast with you.” I was actually bringing a group of public school teens with NCSY to MetLife Stadium to the actual siyum hashas. And he threw in one extra thing. He said, “And at the end of every tractate, you can write an essay on the themes of that tractate, of that masechta along with the Daf Yomi program.

And that opportunity, I’ll be honest, it was so soul nourishing. It nourishes my soul that he gave me this opportunity to share Daf Yomi, to share Talmud ideas with a wider audience. It’s a challenge. It’s tough, but it brings me so much personal joy and has totally enhanced my learning. So I feel like he is my digital chevrusa, he’s my actual chevrusa, and I have so much gratitude to him. But he has an incredible story. And his incredible wife, who I only met fairly recently, she was so, so lovely to speak with. Lisa Ann Sandell, she’s an author herself. I spend a lot more time with Liel because we work on the Daf Yomi together, but being able to sit together with them as a couple and talk about religious change, religious development, how it weighs upon at times and elevates at times the context of a marriage. It is my absolute privilege and pleasure to introduce our conversation with Liel Lebovitz and his wife Lisa Ann Sandell.

What I want to explore and talk about together is how couples navigate religious differences. Lisa and Liel, thank you so much for joining me today.

Liel Leibovitz:

What an absolute joy.

David Bashevkin:

Don’t you steal my lines, Liel. Don’t you dare. Don’t you dare.

So, I wanted to begin with the following question: when you got married, can you describe what your religious identities respectively were like at the point when you met one another and decided to get married? Where were you at that point in your life? Maybe we’ll start with Lisa.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Thanks for having me on the show. I would say that Liel and I were pretty… We were on similar pages. Liel was very clear that he had strong faith in God and I felt less certain in that respect but I knew that Judaism was important to me. I was raised going to an Orthodox shul that was tossed out of the Orthodox Union.

David Bashevkin:

Kicked out? For what?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Kicked out.

David Bashevkin:

What was the infraction?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Mixed seating.

David Bashevkin:

Okay. I was going to say it’s one of the M’s, either microphones or mixed seating.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

It was actually both.

David Bashevkin:

Oh, both.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Both, yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Okay. What community did you grow up in?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

In Wilmington, Delaware. And the congregation was [Hebrew 00:12:34] which sadly closed its doors. It sold its building last year.

David Bashevkin:

Heartbreaking.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Very heartbreaking. We grew up going to shul every Friday night, keeping a kosher home, lighting the candles but I wouldn’t say we were observant beyond that. But it was always important to me. And also because I grew up in a community where there weren’t a lot of Jews and I went to public school, so I was one of a very small minority.

David Bashevkin:

So you felt your Jewish identity?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

So I felt my Jewish identity very strongly. It was really important to me. I went to Israel after college to live and work for a year, and then I came back to the States and I met Liel.

David Bashevkin:

When you met him, how long did you guys date before you got married?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

We dated for a year before we got engaged, and then we had a two-year engagement.

David Bashevkin:

So if I were to ask Lisa when she is in her twenties, when you got engaged, we’re talking and I said, “Do you plan on keeping a kosher home? Do you plan on lighting Shabbat candles?” Did you plan on continuing the home you grew up in or you were already in a place where, “I feel Jewish,” but a lot of the rituals you did not plan on following with in the home that you established?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I expected that I would like candles on Shabbat with children, but not before that. And even before I left my parents’ home, they stopped keeping kosher because the kosher butcher closed his doors and then they were trying to get meat in from Philadelphia. It was like a whole story.

David Bashevkin:

This is the world my father grew up in where you were beholden to another community to even have kosher meat.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Right. And when the butcher in Philly stopped delivering to them, then they couldn’t get kosher meat anymore.

David Bashevkin:

So that’s where you were when you started. And is there another wrinkle that you wanted to add to that?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

No, I think living in Israel, I had volunteered on a kibbutz when I was in college and then was working in a magazine in Jerusalem. I felt very strongly about being a Zionist. I am and always was a Zionist and I loved Israel, but I loved secular Israel.

David Bashevkin:

And as somebody were to ask you again that 20-something-year-old Lisa a denominational question and say, “What do you consider yourself, orthodox, conservative, reformed, reconstructionist?” How would you have answered that in your twenties?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Probably conservative.

David Bashevkin:

Conservative, okay. Liel, your story begins even in a different country. You were not raised in the United States.

Liel Leibovitz:

In a different place in a different time.

David Bashevkin:

You were raised in a laboratory. No, you-

Liel Leibovitz:

In a new world.

David Bashevkin:

You were born in Israel. You grew up with fairly well regarded rabbinic pedigree.

Liel Leibovitz:

I have the zchus as we say in French to be the great-great-grandson of Rabbi Yosef Chaim Zoneke.

David Bashevkin:

Did you grow up knowing that?

Liel Leibovitz:

Oh, it was only mentioned 300 or 400 times a week.

David Bashevkin:

I remember growing up my father would tell me, “We’re relatives with Stacy Schiff.” She’s a Pulitzer Prizewinning writer, but we grew up with that. She’s my father’s, I think, first cousin, first cousin once removed and that was a point of pride. You grew up with, I think, an even more-

Liel Leibovitz:

Same-same. But I think you sometimes Yosef Chaim Zoneke played to the same role in my life that I think Stacy should have played in yours, which is a way of my family saying, “You know the thing that we don’t do? Well, there’s a person out there that kind of did it for us.” Because my grandmother, who was one of the oldest of 12 brothers and sisters, had left Jerusalem behind, had traveled to Tel Aviv, had lived a life that was certainly traditional, certainly not total epicures but already a little bit more lax. And by the time I came around, let’s just say that growing up I was a few cheeseburgers removed from the faith of my father’s. As Lisa said, always had very strong faith-

David Bashevkin:

But you were thoroughly a secular Israeli.

Liel Leibovitz:

I was thoroughly a secular Israeli because I thought and believed firmly and wholeheartedly it didn’t matter what Hashem… Hashem didn’t want me to watch what I eat or say certain words in a certain order several times a day. He wanted me to love him and be a good person and just go out there in this great big world he created and be curious about it. It was more than enough for me. And in fact, I’ve dabbled in yeshivot here and there all over the place.

David Bashevkin:

When you say you dabbled in yeshivot, is that before you got married?

Liel Leibovitz:

Yeah, back in Israel. Loving, caring cousins would say things like, “Hey, why don’t you come and spend a week with me in my yeshiva? Why don’t you come for Shabbat here? Why don’t you go there?” I was grateful for their attention and learned a little bit here and there, but wrote it off as, “Yeah, that’s the thing I don’t do,” which is a feeling that got even stronger when I moved here to New York because here I was. I was now first a student, a doctoral student and eventually a professor, at a whole host of well regarded universities. And I thought to myself, “Well, the great good, the real energy, the real ruach is elsewhere.” It’s in studying Plato and Socrates, it’s in learning Latin and Greek, it’s in being this cultured man of the world. That’s what a real thoughtful person does. And observance, especially again kids not yet being in the picture, felt like something that was a needlessly restrictive kind of remote feeling.

David Bashevkin:

Did it feel antiquated? Meaning at that point can I ask a blunt question, like Yom Kippur, Rosh Hashanah, High Holidays, would that draw you back in your twenties?

Liel Leibovitz:

We have never, ever missed Kol Nidre. Ever.

David Bashevkin:

But even in your twenties, even in that-

Liel Leibovitz:

Absolutely. We would go and then I remember us having very lively discussions in which I would say things, “I just don’t understand why there ought to be just one day of repentance every year. Let’s go home and talk about our feelings and what we regret, but let’s try to do this every day because every day ought to be Yom Kippur,” which is a kind of asinine, self-confident, ridiculous thing that you could only say when you’re 24 and totally carefree, right?

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. And when you got married, for you, what role did you plan on of observance having in your life going forward? Were you like, “Oh, we’ll do Shabbat candles Friday night, kosher kitchen,” or it was just like you weren’t even thinking about it?

Liel Leibovitz:

To the extent that I was thinking about it, which was not often, which is infrequently, I have to say that what came to mind is sort of bare bones minimum. I realized always probably in some unconscious place that I would like my kids to grow up Jewish, whatever that meant, I always had a deep love for the Shabbat rituals: the candles, mirrors, et cetera. But I wasn’t kosher, Lisa wasn’t kosher. In fact, we were kind of actively, outwardly, profoundly, world historically unkosher. And so I thought, “Yeah, I’ll just raise our kids the way we live now. They’ll know their Jews. They’ll have a wonderful relationship with Hashem. They’ll love him and believe in him. They’ll know a little bit about the tradition. They’ll have all the trappings of, yeah, shul here and there and Shabbat here and there, but we’re good, we gave it the office,” type of mentality.

David Bashevkin:

So I’m curious, and I think I want to hear this more even from Lisa’s perspective than yours, something definitely began to change or diverge.

Liel Leibovitz:

Something happened.

David Bashevkin:

Something happened meaning without fast forwarding to where you are now, which is its own kind of ambiguous space, which we’ll get to in a second, but tell me, Lisa, when was the first time you noticed that you and Liel were beginning to diverge religiously in terms of the paths that you were on? What was the first thing that you noticed?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I remember very distinctly Liel and I went out for dinner, I would say it was about eight years ago. We went out for dinner, an Italian restaurant that we both loved and had formerly shared many dishes that were not kosher. And he said to me, “I’m thinking of keeping kosher.”

David Bashevkin:

And your first reaction to that was?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Shock. And then my mind started to spin through all of these possibilities and it felt very apocalyptic for the moment.

David Bashevkin:

For real?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Yeah, like he’s going to start becoming observant in this way that is very foreign to me and that I’m really not comfortable with.

Liel Leibovitz:

I’m sorry to interrupt but I think in your head you’re seeing me like Grammy Hall sees Woody Allen and Annie Hall. You’re looking at me and all of a sudden like—

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Exactly.

Liel Leibovitz:

Streimel, I’m sitting there. Right?

David Bashevkin:

And can I be more blunt? You used the word “observant.” Was that the fear or did you have a latent… The other O-word: orthodox, that he’s going to become… Does that association make you uncomfortable, that he would be-

Lisa Ann Sandell:

To me, they’re the same.

David Bashevkin:

They’re the same, same O-word.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Mm-hmm.

David Bashevkin:

And the fear of becoming observant was the toll it would take on your marriage or was that, “We’re not on the same page anymore,” the restrictions, the otherness? What is it about observance in a marriage that can seem so startling?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

All of it. How could we possibly continue to be compatible if our lifestyles are diverging so dramatically?

Liel Leibovitz:

Hold on, let me push you from the distance of years and time as we are in a safe space here in our living room. As I understand the-

David Bashevkin:

Liel, I have to interject. I have to interject. The witnesses can’t cross one another in the courtroom.

Liel Leibovitz:

All right, your Honor.

David Bashevkin:

The courtroom of the podcast, and we’ll absolutely get to some of that. I want to come back to that-

Liel Leibovitz:

Objection withdrawn.

David Bashevkin:

… to that dinner at the Italian restaurant. Were you aware at that moment when you said, “I’m thinking of keeping kosher,” was it clear to you what her reaction was as she describes it now?

Liel Leibovitz:

No.

David Bashevkin:

Or you were just like-

Liel Leibovitz:

No, no, not at all. Not for a second. Caught me by surprise.

David Bashevkin:

Did you know in that moment that she felt apocalyptic?

Liel Leibovitz:

Oh, it was very evident by her reaction that she was.

David Bashevkin:

But you were surprised by her reaction.

Liel Leibovitz:

Not to me but… Yeah. When I brought it up… I don’t want to call it a process, it’ll be dignifying it with some semblance of thought and structure, which I think all true conversions, all true processes of teshuva don’t happen that way, right? They’re chaotic, emotionally raw, gooey, difficult processes. So I wasn’t really thinking about it. I was just very absorbed by this thing that I was going through and that was going through me. I was sort of happy to share it.

David Bashevkin:

And why wouldn’t you be excited by this?

Liel Leibovitz:

Right.

David Bashevkin:

And you obviously didn’t decide to keep kosher at an Italian restaurant when you sat down. What was going on behind the scenes that would even prompt you to think, “I’m in my early thirties, late twenties…” When is this?

Liel Leibovitz:

Early thirties.

David Bashevkin:

What was going on behind the scenes that she was clearly maybe unaware of or didn’t realize how immersed you had become that you were considering, “I’m going to start keeping kosher.”

Liel Leibovitz:

It is so profoundly difficult for me to capture it because-

David Bashevkin:

Were you studying, were you going to shul? Because it caught her by surprise. She didn’t know something. Were you waking up in the middle of the night quietly dialing up your chevrusa and whispering?

Liel Leibovitz:

That came later, this Murano vibe that you’re describing.

No. Look, I think if I’m rationalizing it, which is already forcing it into a pattern that is a little bit too neat to capture the true storm, I think a bunch of it came from observing the world around us change. I think a lot of the political socioeconomic turmoil that we’re seeing haunt us now was evident or beginning to be evident to me back then. It did not feel like America was the same kind of radiant, sunny place it had been for me when I chose to move here from Israel in the late nineties so a part of it had to do with that.

But honestly a part of it had to do with a much more innate inner calling, just feeling something inside, going to this restaurant and feeling it’s not right for me to order the prosciutto. Why? I haven’t a clue. This was before study, this was before daven. This is before everything. I just went and felt like this is something that my soul is calling out to me to do. Stop doing that.

David Bashevkin:

And you paid attention to it?

Liel Leibovitz:

I paid very close attention to it.

David Bashevkin:

Let’s fast-forward a little bit. Did you start keeping kosher at that Italian restaurant?

Liel Leibovitz:

Yes.

David Bashevkin:

Was at the beginning of-

Liel Leibovitz:

Yes.

David Bashevkin:

That was the end.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

That was the beginning.

David Bashevkin:

Mid-Italian restaurant.

Liel Leibovitz:

It was the beginning and the end.

David Bashevkin:

Meaning you showed up to the restaurant?

Liel Leibovitz:

Yep.

David Bashevkin:

You made the reservation and midway through-

Liel Leibovitz:

There you have it.

David Bashevkin:

… something changed.

Liel Leibovitz:

“Hey, will we be having the shrimp scampi?” Like, nope.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

We sat down, we ordered a drink.

Liel Leibovitz:

We’ll be happy with salad tonight.

David Bashevkin:

Did you also not order at that point? Were you like, I guess, “Am I not having kosher either now?” Or were you, “I’m still…”

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I don’t remember in that moment. I think we did not order, because we used to share food.

David Bashevkin:

Gotcha. “I guess we’re sharing a salad,” or…

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Yeah.

Liel Leibovitz:

It was a long dinner, David.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I just remember feeling very uncomfortable. We ordered vegetarian dishes and I felt uncomfortable ordering treif.

David Bashevkin:

In front of Liel?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Specifically in front of Liel?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

That passed over time.

David Bashevkin:

Okay.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

That passed.

David Bashevkin:

Gotcha.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

For the record now I keep kosher, but we can get to that.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, well-

Liel Leibovitz:

Don’t reveal. Don’t spoil the ending.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Spoiler alert. But for years I did not hesitate to order treif.

David Bashevkin:

Even in front of Liel?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

In front of Liel.

David Bashevkin:

At that point, when you’re driving home, do you have a conversation with Liel at that point? What’s happening right now? Or did you both kind of, “Let’s don’t ask, don’t tell and let’s just see where this takes us.”

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I was very upset. I shut down. I did not ask him questions about what prompted this. In retrospect, I wish I had had more presence of mind to be more empathetic and curious and loving, frankly. But I was so freaked out.

David Bashevkin:

You were freaked out?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Now, fast-forward a little bit. What happened after the kosher conversation? You shut down. When was the next time that there was a point of divergence where you both became aware that you are on different paths?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

There was a car trip in rural Pennsylvania or something, and all I remember is we were talking about why I’d reacted the way I did.

David Bashevkin:

That finally came up years later.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

It wasn’t maybe years later.

David Bashevkin:

Several months later.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

A year? I don’t know, something.

David Bashevkin:

Okay.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

And I remember saying, “I just feel like it’s going to snowball into your wanting to be shomer Shabbat and fully observant and it feels like a path that I can’t join you on.

Liel Leibovitz:

You’re one knot away from a full Na Nachman. Yeah.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I felt like you were going away from me and I was so scared and sad and I didn’t know how to express myself well because the fear and anxiety was so overpowering and I know I wasn’t kind to you in that time.

David Bashevkin:

When you say “not kind,” were you derisive, mocking to the process or you would just shut down and ignore and not be openhearted to it?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I don’t think I was derisive or mocking. And Liel, you can correct me if I’m wrong about that. I wasn’t supportive.

David Bashevkin:

Did you have somebody else in your family where religion broke up a family? Because it sounds like you were calling upon something, meaning that you would become so concerned. I know in my family we have a close family member, most of my family is not orthodox. My father’s the anomaly, then we’re Orthodox, and we have a family member who her either uncle or somebody became Orthodox and it didn’t really refine his character as much as we hope sometimes the movement towards observance would do. It really created this sense of otherness, betrayal. The number one goal was don’t walk down that path. And I’m curious for you that you had such a visceral reaction towards the journey and transformation that Liel was taking, what memories or family stories was it calling upon?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I would say there’s a very similar family story in my immediate family.

David Bashevkin:

Without being too specific.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

So you had the archetype of religion becoming a wedge in a family and watching it happen to you was calling upon all of that?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Yeah, it was pushing some buttons.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. Did you express that to Liel?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

No, I was not expressing anything except for fear.

Liel Leibovitz:

In fact, when Liel brought up this very proposition, you said, “No, it’s not what this is about.”

David Bashevkin:

Oh, you suggested this?

Liel Leibovitz:

I’m not as good a therapist as you are, but I’m a decent apprentice.

David Bashevkin:

So you’re in this car ride and you’re having this conversation. This time you’re again telling him what you’re feeling. Liel, what did you say? Were you able to express better what is calling you or what direction you’re headed in? Or you still were at a point where it’s the open road, let me press the gas and see what happens.

Liel Leibovitz:

I’m very curious to see if Lisa would call me out on what I’m about to say as being way too orderly, self-serving. Here’s how I’ll characterize my reaction. I feel like at first I did my best to register the completely legitimate emotional shock that this caused and do my best to guarantee that, A, I am by nature someone given to very strong feelings, but not someone given to radical, world-titillating, apocalyptic changes. And also that I believed very firmly in darchei noam and that I thought that any kind of observance that upset the family dynamic and that tried to assert itself on other people without them being emotionally ready for it was just not my way. I feel that I was not successful at communicating it. At which point, frankly, feeling Lisa’s very intense combination of anxiety and closeness, I joked before I said feeling like a Murano but that’s pretty much how I felt for [Hebrew 00:30:02]. I should study and daven and do this entire process completely privately.

David Bashevkin:

In secret, almost.

Liel Leibovitz:

In secret away from anyone else’s prying eyes.

David Bashevkin:

And would you do that?

Liel Leibovitz:

Yes, absolutely.

David Bashevkin:

Like what? Give me an example of something that you would deliberately do in private.

Liel Leibovitz:

If I knew that I had to pray shachris, I was like, “I’ll do it when I’m alone. I’ll do it when I’m alone in the house.” If I knew that I had to, not had to, wanted to study, I was like, “Okay, well, it’s 11:30 at night, Lisa’s asleep. Now it’s time to open the sefer and sit down and learn something.

David Bashevkin:

Lisa, was he a successful Murano or did you know that there was a period where he had this dual identity? Did you ever bust in, he’s like, “What are those marks on your arm?”

Liel Leibovitz:

What’s that on your arm? Nothing.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

No, I knew, I knew. And I would say, Liel, that while my reaction sucked, I don’t think you were-

Liel Leibovitz:

Much better?

David Bashevkin:

What did he do that could have been better?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I think he was rightfully very hurt by my reaction, and I think he withdrew and stopped trying to talk to me about it.

David Bashevkin:

To share this part of his life with you?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Very, very quickly. It didn’t take a lot.

David Bashevkin:

He got the memo right away.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Maybe almost got the memo too quickly where he’s like, “Okay, you don’t want me to share this part of my life with you?”

Liel Leibovitz:

I admit to that wholeheartedly. I think that’s correct.

David Bashevkin:

And said, “This is not going to be a part of my life that we are building together.”

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Right.

David Bashevkin:

And you basically entered two separate rooms.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

And I don’t think that you really made an attempt to explain anything to me. You just said, “I’m going to keep kosher,” and that was it.

Liel Leibovitz:

I think that’s true. Although honestly, again, in my defense, I’m a decade in. If you ask me to explain it is so incredibly difficult for me to tell you what had happened.

David Bashevkin:

It’s not like you read a book on kosher and the next morning you’re like, “Okay, I’m going to-”

Liel Leibovitz:

Saw a Netflix show, be like, “Hey, this shit looks cool. Let’s go full black hat.” No, it really was a sense of a deep, profound spiritual calling that said, “Do this now.” And the naaseh vi nishma moment was complete. Now at least I acknowledge and apologize for this, but now I’m countering like a good Jew always should. Part of my difficulty to communicate it and Rebbenu Bashevkin would maybe help us resolve this thing to an extent. I felt like a lot of what I was going through was almost indescribable without being experienced. There’s a reason why great writers fail when they try to describe food or sex or love because these are things that have to be experienced. And I said to her, “I can’t tell you what it’s like to wake up every morning, put on tefillin, daven shachris and start your day with complete connection and gratitude to Hashem. You have to do it.” I could sit here and talk until the cows come home, but it’s not going to make any sense when the words leave my mouth because the naaseh vi nishma will hear and will do it. That’s real.

David Bashevkin:

There’s a beautiful idea from Rabbi Tzadok that we all knew would make an appearance.

Liel Leibovitz:

It has been 26 minutes, it’s the longest you’ve ever gone.

David Bashevkin:

But Rabbi Tzadok says that when we talk about our reasoning for why we do things, the language that we use in Hebrew is the taam, the taamei hamitzvos, the reason why we are doing this. The word “taam” also means “the taste,” and taste is something that is nearly impossible to share unless you imbibe it. It’s almost indescribable unless it’s within you, and it’s within your mouth, and it’s swooshing you around, and it’s on your lips. And a lot of times the reasoning of how we interact with commandedness or observance or yiddishkite or whatever word you use to describe, it’s very hard to transmit and diminish to this is the reason. It’s more like this is what it tastes like. And it’s very hard to transmit a taste if the other person is unwilling to look at the dish.

But at the same time, I appreciate the fact of how cataclysmic religious differences can play particularly in the familial life because to me you’re bringing the very point of yiddishkite and religion to its source, so it’s like high volatility. Yiddishkite is all about the family unit so if it’s not aligned it can get nuclear and explosive, if it’s misaligned.

So I’m curious, was there a breaking point where either of you said, “Enough,” almost like ultimatum, “this cannot continue.” What reversed course? I’m looking at you sitting next to each other; there seems to be more calmness, more understanding. Why didn’t it progress and just go on different paths? Why are you even able to talk about it today? What was the turning point that gave you each the vocabulary to have this conversation?

Liel Leibovitz:

I have an easy answer but it’s probably not the correct one from Lisa’s perspective. My answer is Hashem. Yeah, I felt hurt. Yeah, probably withdrew too quickly. Yeah, went very far on my own. But never stopped.

David Bashevkin:

Never stopped what?

Liel Leibovitz:

Never stopped with the process. Never stopped being present and open for it, for observance, for yiddishkite, for love of all things Jewish. And I think it has less, or let me rephrase, nothing to do with me and everything to do with the incredible, incontestable value of Judaism. I think eventually not just Lisa but also our children found themselves independently, perhaps despite of me or in spite of me, not because of me, drawn to it.

Fast-forward some years, here we are, we all keep kosher. Now we never said to the kids, “You must. You may not order the lobster roll.” It was very important to us that it’d be an independent choice that they make out of love, and they’re still young. I can’t tell you how happy and proud I am that they both made it independently. Said we’re going to give up these things that we know, the tam, the tastes that we know and absolutely love because we understand there’s a greater calling, that Judaism and observance prefers a greater calling. Was it, again, in spite of me rather than because of me?

David Bashevkin:

To me the real answer for this question must only lie in Lisa’s memory and recollection because you charted a path for yourself and your processing, but I’m really curious for Lisa. It sounds like at least in the more recent part of this story you’re the one who had to change. And I’m curious, Liel continued on this journey and you to whatever degree joined him or became more a part of it. What changed for you?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Well, I’m going to back up a little bit.

David Bashevkin:

Please.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

And counter Liel’s counter and say that-

David Bashevkin:

He’s a very unreliable narrator, that’s why I have to…

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Totally.

David Bashevkin:

A very important…

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Liel wasn’t as open with me about his process. And he can say it was an awakening, and it’s indescribable, and it’s hard to articulate what drew him down this path but you did say at the beginning of this conversation that part of it was the world around you had changed and so you started to look elsewhere for, I don’t know, a center point and meaning. I think maybe if you had articulated that part of it to me early on maybe conversations would’ve gone differently. That’s in the past, so…

David Bashevkin:

Okay.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Okay, that’s stated for the record. But moving on, I would say that the reason we were able to sustain this marriage and relationship as you were going through this process is not just because of Hashem, although I guess ultimately it is because of Hashem, but also it was the huge amount of love-

Liel Leibovitz:

Oh, sure.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

… and goodwill-

Liel Leibovitz:

Absolutely.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

… that we feel for each other and the strength of this marriage that was there from the get go.

Liel Leibovitz:

I could not agree more obviously, but how does that explain your journey?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I don’t think it’s obvious.

Liel Leibovitz:

How does that explain your journey?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

But that’s what the question was at the outset. Anyway, my transition happened because I think I, later than you, reached the same conclusion about the state of the world. But also we elected together to put our kids in Jewish day school before Liel started to keep kosher. Before that was even I think an idea in his mind, a couple of years before you had even started to entertain it.

Liel Leibovitz:

A couple of years and a couple of shekels before I started entertaining.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

That was a priority. And in the beginning, in the first couple of years when our daughter was starting at the day school, I remember feeling like this is all very foreign. This feels scary and she’s going to have all of these points of reference that are completely unfamiliar to me. They had a family tefila for the class every week and I went every week and I just felt very deeply uncomfortable.

David Bashevkin:

Did you remember the prayers from when you were a kid?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Some, but-

David Bashevkin:

Most none?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I never… No. I remembered adon olam.

David Bashevkin:

Okay. Oh, that’s a classic.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

That’s a classic.

David Bashevkin:

That’s a keeper.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

But I had never prayed shachris. I didn’t know the prayers. So, fast-forward a few years, it’s like the most meaningful, beautiful part of my week. I’m so grateful for it. And I’ve learned alongside the kids just from going to tefila every week with them. So I think in part learning alongside them and just becoming more familiar and at home with that aspect, with prayer, has been a huge, huge, really sea change in my life.

David Bashevkin:

Can you explain why did you find yourself davening for clarity or comfort in this meeting? I’m trying to figure out, when this first began, you felt… You used the word “apocalyptic.”

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Right.

David Bashevkin:

And something changed where it’s not just apocalyptic, it’s not just betrayal, it’s not just the world is not ending, but you actually derive strength. You’re shifting away from “We can preserve our marriage” to a place where “our marriage, our family life is strengthened from this.” What was the name of the highway that brought you to that discovery?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I don’t know. I don’t know that I can pinpoint.

David Bashevkin:

Maybe Liel, maybe it was Hashem. I happened to have liked your pushback and I was annoyed when Liel said Hashem too. But rephrasing that question of this shift and you had real… It sounds like trauma might be too strong a word or it might be the exact right word because I know having come from a family where observance and orthodox is a very real scary thing, it’s what tears families apart. It is the point of judgment. It’s the point of we’re different, we’re other, we can’t eat together, we can’t… It’s what tears at the fabric of family and to be able to shift. And now you’re in a place, seemingly, where all of this history is paved over, that you’re able to actually derive strength from the very place that brought you discomfort. I’m just curious. It’s similar to Liel’s awakening. I’m struggling to find what was the realization, what was the shift in thinking that allowed you to embrace this?

Liel Leibovitz:

I’ll talk a little bit just as Lisa collects her thoughts, a little bit in defense of me and a little bit in praise of Lisa because I understand why my answers may come off as annoying.

David Bashevkin:

Lovingly annoying.

Liel Leibovitz:

No, no, I understand that but that’s the relationship I’ve always had with God: this kind of immediacy, this kind of deep current of emotional, personal, intimate connection. That has always been there for me. I understand that is a huge privilege and perhaps an anomaly.

I also understand that most people think about things that I never once stopped to entertain, I actually literally never once stopped to think about, and perhaps that explains why I was so prickly in my response but I never actually stopped to think about there potentially and possibly being any negative real world implications to this thing because this thing to me was truth and beauty. And when truth and beauty knock on your door, you don’t ask, “Wait a minute, but what will we do with the refrigerator door between sundown and Friday, and sundown and Saturday?” You’re like, “Hey, wow! Look, it’s radiant and gorgeous. I want to bathe in this.” I understand that’s a weirdo kind of off-to-the-side type of relationship.

So now back to you, Lisa. I’m curious because honestly I don’t think I had anything to do with any of it. So, what was it?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I worked very hard for years to overcome the anxiety that this caused me because it was really all about anxiety. I was anxious that if we started to keep Shabbat, then we couldn’t go travel to see my parents, or my parents would think we were weird, or we wouldn’t be able to eat with my parents, or our friends would think we were weird.

David Bashevkin:

There’s that Philip Roth story. What is it, Eli the Fanatic?

Liel Leibovitz:

Right.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Right.

Liel Leibovitz:

Well, my friends already think I’m weird, so that’s probably-

David Bashevkin:

Well, that’s not so far off.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Right.

David Bashevkin:

But I hear I hear why for you, before you know it you’re going to pass by a mirror and you’re going to be looking like you’re on a Shtetl. When did this happen?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I really thought about this for years and really just worked at it and reached a point where, I don’t know, it’s like I actually overcame an anxiety.

David Bashevkin:

How did you work at it? Is that therapy? Is that prayer? Is that meditation? Is that just like…

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I did all those things.

David Bashevkin:

Is that work on the marriage, reminding yourself, “Why are we in this?”

Lisa Ann Sandell:

It was all of it. I did do meditation, I did do therapy, I did pray, I did talk to Liel a lot. We talked a lot.

David Bashevkin:

You started speaking a lot about this.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Mm-hmm.

David Bashevkin:

What would those conversations be? Would you try to find out more about his process or you would just share your anxieties and say, “This is hard for me.”

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Both. It was a lot of expressing my anxiety but I do ask him a lot of questions now.

Liel Leibovitz:

And again, to be honest, I feel in the context of our marriage, and it’s ironic since so much of what I do publicly is talk about faith and observance, but I feel like I was completely useless to you precisely because my own path has been so inflamed.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

You weren’t useless because you’ve always been the man I love, the man I admire and respect and think the world of in every capacity. So once I was able to sort of work through that anxiety, I could look to you as a beacon, almost.

David Bashevkin:

Can I add in one component? I wasn’t sure if I was going to bring this up and this is really directed exclusively at Lisa. Aside from Liel being on this very exciting, imaginative, volatile religious journey, he has an added component where he’s actually quite forthcoming in a public space in his writings. Not just his religious opinions, his political opinions, which can sometimes be idiosyncratic, not what you would associate with a New York liberal Jew.

And I’m curious for you if the public role of Liel, and specifically in his political views, which can be, can I use the word, and I say this with love because we know we love each other, could be abrasive at times. He doesn’t sugarcoat. It’s not a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down. He gives you the medicine straight away and this is what he feels you need to hear, and he says it very straight. And you could be walking around in the city with your other maybe more liberal friends and they’re like, “Did you hear what your husband just wrote?” Or you could overhear people talking about things that your husband’s writing about defending, aggravating, roiling up. And for you, in some ways it feels like the rebbetzin who’s married to the rabbi who gets up, gives the sermon that half the shul feels alienated by, and you’re like, “I didn’t give the sermon.”

Lisa Ann Sandell:

My first loyalty is to him and that will always be the case when I am outside the home.

David Bashevkin:

I love that answer. But has that ever come up where friends or acquaintances, obviously your closest friends wouldn’t put you in that position, where you’re hearing criticism of your spouse in the social circles that you may bump shoulders with?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Nobody has been critical of him to me. We’ve definitely been with friends where people are like, “What happened?” Or, “What was that piece?”

Liel Leibovitz:

We’ve definitely been dis-invited from some social settings.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Yes, I have.

David Bashevkin:

You’ve had people who have distanced yourself.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Yes. Not close friends.

David Bashevkin:

Does that hurt you? You’re like, “I didn’t do anything.” Or that actually feels like it tests the allegiance and you’re like, “I’m choosing my family.” Or this is isn’t a game for you.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

It wasn’t even a question.

David Bashevkin:

It wasn’t even. I love when I see spouses not fighting and fighting the battles of their spouse, but a deep loyalty where this isn’t even a choice. I’m not letting some public article disagreement test the strength of my home.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

There was a moment when there was a political turn and it was so different from where we both were 10 years earlier.

David Bashevkin:

You were more liberal when you first got married?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

We both were, yes.

David Bashevkin:

Meaning your journey, those seemed to be somewhat intertwined.

Liel Leibovitz:

Yes.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

There was a moment, I think, when some of Liel’s political views sort of took a lot of our close friends by surprise. And I would say this wasn’t always how… I don’t know what I’m trying to say, actually. Can we scratch that?

David Bashevkin:

No.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I don’t know what-

David Bashevkin:

No, this is so important because what’s so fascinating to me is that his political turn does not seem to have tested your resolve in the same way his religious turn has.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

No, it did not. Not at all.

Liel Leibovitz:

Not at all.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Not at all.

David Bashevkin:

And why is that? What would you say the distinction is?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Because there was nothing about his politics that would impede the way we lived our lives.

David Bashevkin:

Meaning that’s not going to change the fabric of your home?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Correct.

David Bashevkin:

But religious observance absolutely can and will.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Right.

David Bashevkin:

And whatever he’s writing about, okay, you might not be having the same ladies who lunch circle, but you’ll get over that. That wasn’t as quite as important to you.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Correct.

David Bashevkin:

That’s fair.

Liel Leibovitz:

I’m more the lady who lunches in this house, but okay.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I always know that Liel is who he is. Yes, he can be loud, but he is such a good, fundamentally good, courageous person that I will always know that about him no matter what he writes or says in public.

David Bashevkin:

I’m very struck by the difference in your affect in the tone in which you express yourself. I find it quite charming and compelling how you have this, can we use the word “abrasive” again? We’ve used that too many times? And there’s a softness, just a discovery, slow curiosity. And Liel’s like, “This is what I want,” grabs it by the neck. It’s very sweet. It’s very charming.

I’m curious now, I really want to open this up because this is an issue that so many people are lacking direction because there are very few couples who are willing to open up. There’s an intimacy to talking about differences in a marriage. And before I ask you about advice to other couples and what you would do differently, have you found a stasis now? Are there still religious aggravators that come up? And if so, what are they?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I would say Shabbat is the big-

David Bashevkin:

Is the next frontier.

Liel Leibovitz:

The final frontier.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

The final frontier.

David Bashevkin:

The final frontier, okay. Do you feel like you have the skills to navigate this or it still feels apocalyptic at the end?

Liel Leibovitz:

I’m going to put it all on the table. We’re sitting here pretty much precisely where we were sitting three years ago.

David Bashevkin:

We are surrounded by alcohol on all sides just so we understand what this room is.

Liel Leibovitz:

Yes, we are and it helps. And I said to Lisa, “I know your heart. I know your soul. I know your values and I know how deeply and truly you’re connected and passionate about all the right things. Mark my words: there will come a time and it will be in the next five years when we will be keeping Shabbat together as a family.” And Lisa looked at me and said, “There is no freaking way that this is going to happen. Strike that, scratch that. It’s never going to happen.” I was like, “Okay. Me and my friend Hashem beg to differ.” I don’t think I’m divulging too much here when I say that last week Lisa said, “I think we should give this thing a try. Let’s give it a little go here.” And I love it because it was all Lisa.

David Bashevkin:

Lisa, is that a fair recollection minus the “fricking,” which I assume was edited out because it’s a family podcast?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

It’s pretty accurate. I’m really struggling, though. Really, I’m reading a lot and trying to study a lot, and I really feel moved in a way that I never felt before but Shabbat feels very restrictive. And I’m really, really struggling with that. But I do feel like knowing that it’s so important to Liel and knowing how I’m feeling at this moment in time, that we should try it. And the wording I used, the way I framed it last week was, “I would like to try it for a limited time and see how it goes.”

David Bashevkin:

I think that’s the best way to try anything. If the reason is the taste, then you put it in your mouth, you swish it around, see what… You don’t have to commit to the full bowl of ice cream or steak, or whatever it is. And I always say, especially with Shabbat, there’s never been a more difficult time to observe Shabbat than the modern world we live in now, and there’s never been a more compelling time.

I tell my students this constantly, you could place your bet on Shabbat. It is restrictive and it is difficult but the meaning and the purpose is amortized over the entire course and duration of your life. You’ll always be getting dividends from Shabbat.

The fact that you’re having these conversations still, this kind of slow and steady discovery, and it seems like you’re not on separate roads. You might not be on the same exact sidewalk. The only thing I want to push back on is I don’t fully believe you that this is framed as a concession to Liel.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

No.

David Bashevkin:

For Liel.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I don’t feel like it’s for Liel. I see it as I’m his wife. I care about him. I want him to be happy and fulfilled, and feel like he’s living his best life so it’s important to me. I know this is important to him.

David Bashevkin:

I still don’t fully believe you. I think there’s-

Lisa Ann Sandell:

But it’s not the reason. If that were the reason I would’ve done it 10 years ago.

Liel Leibovitz:

What’s compelling you?

David Bashevkin:

But there’s a Lisa part of it.

Liel Leibovitz:

Exactly. What’s your draw?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

My draw is the reading and the studying I’ve been doing has been inspiring, moving, and I feel more just spiritually energized and activated in a way that I haven’t before.

David Bashevkin:

I want to close by reflecting on some of the mistakes or missteps that you’ve made. I’m just curious, almost as like a yes or no, do you feel like you’ve forgiven Liel? And Liel, do you feel like you’ve forgiven Lisa for some of the tension or distance that each of your respective decisions have made?

Liel Leibovitz:

A hundred percent on my end, absolutely. Not just because I love her very much and care about this marriage more than anything and understand both my missteps and her anxiety.

But also independently or to the side of it, to see Lisa’s own journey, to be in Cape Cod last year sitting in our favorite very seafood-heavy restaurant and see Lisa being, “I’m having the salad tonight.” It’s astonishing. And I know she’s not doing it for me or for shalom bayis or anything like this. She’s doing it because she’s really opened up and traveled to a wonderful place. So, I’m giddy.

David Bashevkin:

And Lisa?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I don’t know that there was anything I needed to forgive him for, but there’s no…

David Bashevkin:

Let’s close. I’ve been doing this Intergenerational Divergent series. This is the third year that we’re doing it. A lot of people reached out on the couple’s question and there are really two types of couple dilemmas, we’re covering both. One is a couple who lapses; there are observance lapses. And the other is when one spouse moves closer and this is-

Liel Leibovitz:

Jews, man! It’s never-

David Bashevkin:

It’s never easy.

Liel Leibovitz:

It’s never easy.

David Bashevkin:

This is obviously the latter. Both are extraordinarily common. I believe that part of what we need in this moment, in this generation right now, it’s more guidance, more conversation about looking at the family unit as the center, as the kodesh kedashim, as the heart, the inner sanctum of our religious lives, and not looking at religion and family as adversaries, competition for attention, but looking at our family life as the highest expression of our religious lives.

And I’m curious given your own experiences and the mistakes that have been made, what advice would you give to a couple, but who someone whose spouse is moving, becoming, whether you want to use the word observant, orthodox, religious, whatever word you want to use, every word. Some people are going to find either offensive or inaccurate or whatever it is, but we’ll use all of them. What advice would you give that spouse given your own experiences of how you first handled that?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

My advice would be to accept your own anxiety and sit with it, and also to remember who your spouse is and the quality of their character and to try to always keep that at the front of mind ahead of the anxiety and to ask questions. That’s my biggest regret, that I didn’t ask Liel more questions.

David Bashevkin:

And how did you remind yourself of that part of Liel that could have so easily have been overwhelmed and suffocated by your anxiety? Did you have any rituals? I know somebody who’s quite close to me who, like any marriage, has gone through rock. They keep a picture of their spouse and tacked onto the picture are adjectives that clearly are the reasons why they love this spouse. And when I saw that in this home, it reminded me of this is a marriage that is putting in work to remind themselves of why are we here. I’m curious if you had a way that you reminded yourself of the Liel, of the love, the chessed neurayich, that initial loving kindness that you had for-

Liel Leibovitz:

Would adjectives like “adequate”?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

No.

David Bashevkin:

Abrasive. No.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

No.

David Bashevkin:

I’m looking around. I don’t see any pictures of Liel with adjectives.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

No, no adjectives. But I just watched him with our kids and reminded myself to be kind and accepted his kindness back. And tried to always -even if I was very worried and anxious about his path that seemed very divergent from mine- I still felt connected to him on so many other levels and tried to always stay focused on that. And to just keep remembering to be kind.

Liel Leibovitz:

I want to add to what Lisa’s saying, which I think is very beautiful, and I certainly share in spades. There’s a great scene in a not-so-great movie, Lincoln by Steven Spielberg, in which a leader comes to Lincoln and says, “I will absolutely not stand for your wishy-washy, hesitant, playing politics on the question of slavery. It is an absolute moral wrong and we’re going to go out there and we’re going to say it. We’re going to state it because the country needs to see and hear that this is completely wrong.” And Lincoln, in Tony Kushner’s brilliant moment of telling, tells this person the following story. He says, “My first job used to be as a land surveyor, and when I surveyed land I would walk out there, and the first thing that we would do is we would look at the North Star because that’s obviously how we knew where we were going. But then I learned very quickly that if you are only looking at the North Star, your chances of quickly falling into a ditch are very high.”

It’s a great reminder of looking both at the stars above you but also at the dusty ground underneath your feet, which I think is maybe the best advice I could give couples because I certainly messed it up.

David Bashevkin:

You were just looking at that North Star.

Liel Leibovitz:

So star heavy, like, “Oh my God, look at me! I’m learning. I’m davening. I’m growing. I’m doing all these great things.” But meanwhile there’s a whole relationship happening that I wasn’t always as good about with Lisa’s shooting me incredulous looks.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I’m just wondering, does that make me the dust?

David Bashevkin:

No, I think the marital strife.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I’m kidding. I’m kidding. I get it. I get it.

David Bashevkin:

I happen to really like that.

Liel Leibovitz:

I rest my case.

David Bashevkin:

That analogy, though, I take some issues with the subtle dig at the movie. I thought it was a fairly solid movie. You need to consult with Wikipedia to just know everything that’s happening there, but that is quite beautiful. If you get so focused on that North Star, you kind of forget the ground underneath you and you can quite easily fall into a ditch.

I always end my interviews with rapid fire questions. I’m curious for each of you if there is a book that you could recommend that either informed the way you navigated these relationships, the way that you navigated maybe your anxiety surrounding it. It doesn’t need to be a couple’s book. It could be anything: fiction, non-fiction, but a book that comes to mind that either gave you strength during this journey or helped you navigate some of the minutiae, the issues that came up.

Liel Leibovitz:

Easy for me.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. What is it?

Liel Leibovitz:

Synagogue by Rabbi David Bashevskin.

David Bashevkin:

Stop that.

Liel Leibovitz:

I’m serious.

David Bashevkin:

I really appreciate that.

Liel Leibovitz:

For the gift of Rabbi Tzadok alone, and for your warmth and your wisdom. And again, the willingness to not just talk about but look at failing at something.

David Bashevkin:

And it’s so interesting because Rabbi Tzadok, his marriage did fall apart because he was looking, I think, at that North Star. He was criticized by other rabbanim and I believe… It’s a little debate, but I believe it’s something he lived with a great deal of regret and felt that it was connected to his struggle to have children, the fact that his religious ideals impeded and eroded his first marriage. That stayed with him undoubtedly his entire life.

Lisa, I’m so curious if there’s a book.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I would say Daniel Deronda by George Eliot.

David Bashevkin:

I love that. And in a sentence, why did that come to mind?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Because the revelation, I guess, spoke to me at a time when I needed to see it.

David Bashevkin:

I absolutely love that. If somebody gave you a great deal of money and allowed you to take a sabbatical and go back to school and either get a PhD or write a book on any topic of your choosing for as long time as you needed, what do you think the subjects and title of your PhD or book would be?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I think I would write about the Jews of Spain.

David Bashevkin:

Why the Jews of Spain?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Well, my mother’s family is long ago from Spain.

David Bashevkin:

Is she from a converso family?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I don’t think so. They ended up in Russia, but she traced her ancestry to Spain.

David Bashevkin:

Fascinating. Liel?

Liel Leibovitz:

I’d write a book called How the Talmud Can Change Your Life: Surprisingly Modern Advice from a Very Old Book, coming this October from Norton Preston.

David Bashevkin:

Well done, my friends.

Liel Leibovitz:

Honestly, because I live life, as you mentioned publicly, abrasively loudly, the greatest gift I could have is not writing. The greatest gift I could have, this even rhymes, it’s a year at the Mir.

David Bashevkin:

A year at the Mir.

Liel Leibovitz:

In a great yeshiva where I don’t have any responsibilities and all I have to do is just learn. Nothing, nothing would be a greater gift.

David Bashevkin:

That is absolutely beautiful. My final question, I’m always curious about people’s sleep patterns. What time do you go to sleep at night and what time do you wake up in the morning?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I usually fall asleep putting my son to bed.

David Bashevkin:

What time is that?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Like, 9:00. Wake up around midnight, go to bed.

David Bashevkin:

Putter? You putter a little bit?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I putter. I do the dishes, whatever. And then I go to bed around 12:00. Well, 1:00. And then usually I sleep terribly and I wake up all throughout the night. I’m usually up around 3:00, 4:00, but I only get up at 6:30.

David Bashevkin:

Wow, okay. Spoken like a true brethren of the anxious faith. Liel, what time do you go to sleep at night and what time do you wake up in the morning?

Liel Leibovitz:

Not anxious at all, but very late and very early.

David Bashevkin:

I need numbers, Liel.

Liel Leibovitz:

I’m cursed by very little.

David Bashevkin:

I need numbers. Do I have to ask Lisa? Lisa, what time does Liel go to sleep at night and what times does he wake up?

Lisa Ann Sandell:

I would say you’re frequently in bed by midnight and you wake up around when I do.

Liel Leibovitz:

I would say before that.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Sometimes.

David Bashevkin:

Liel and Lisa, thank you so much for joining us today.

Lisa Ann Sandell:

Thank you so much for having us.

Liel Leibovitz:

Always a pleasure.

David Bashevkin:

When God creates man, there is a remarkable verse that I think many people are familiar with. When he creates humanity, he creates a spouse for the first man. And the way the Torah describes it is that man needs an Ezer Kinegdo. He needs a helpmate alongside of him. And Rashi notes that it’s not just an Ezer, it’s not just a helpmate, but there’s a component of Kinegdo, an adversarialness, an opposition. You don’t just needs somebody who’s, “Yes, yes, yes.” A great spouse is somebody who challenges, who pushes back, who through the refinement of the dialogue, you are really able to uplift and create something new altogether.

And there is a remarkable essay from Rabbi Sacks where he actually considers the fact that our relationship with God in many ways is compared to the relationship of a spouse. And the Jewish people and God, so to speak, have this spousal connection with one another.

And he turns to the way that the Torah describes that first spouse, the Ezer Kinegdo a helpmate alongside of him. Rabbi Sacks writes something that I think is so remarkable. He presents a radical possibility that God says, “I will make man in Ezer Kinegdo. The rabbis,” Rabbi Sacks writes, who had a very fine ear for nuance, “understood that this is a contradiction in terms. An Ezer is somebody who helps you and Kinegdo is somebody who opposes you. I will make man somebody who on the one hand is a partner but on the other hand is capable of opposing him. Now, what more precise definition is there of the Jewish understanding of the relationship between God and humanity than that?”

“We,” writes Rabbi Sacks, “are God’s ezer kinegdo. On the one hand,” as the rabbi said, “we are his shutef bmaseh bereishis, his partner, his helper in the work of creation. On the other hand, we are the only beings in all of creation who are capable of being Kinegdo, of rebelling against God. Ezer Kinegdo does not merely describe Eve’s relationship to Adam; it describes humanity’s relationship to God. This, then, creates the incredible possibility that I want to stay with you because if I’m wrong, forgive me that the words of God lo tovlehiyot adam levado, when God says it is not good for man to be alone are the nearest we get to God’s commentary on his own being.”

“And to that ultimate question, which haunts us all, which is: why did God create the universe? As long as we think of God in classic philosophical terms, that line makes no sense at all. If God is omniscient, omnipotent, Platonic, Aristotelian, it’s impossible to comprehend that God should lack anything. But if for a moment we can imagine that God is almost describing his own existence, keilu, as if, then the reason why God created humanity like the same relationship that we see among spouses, it’s both to be a partner, but also to challenge, to question, to discover, to push back, to clarify that we, so to speak, with God are his ezer kinegdo, both a partner and also somebody who can push back, refine, critique, elevate the very notion of godliness in this world.”

And I think the love that can be challenged, the love that can be dissolved, the love that can be rebelled against yet still remains intact, that spousal love, in many ways is the most powerful love because it’s the love that only exists once both parties commit. And there’s this absolutely beautiful song by Schlomo Katz, it’s a cover to a song by Michael Shapiro that they republished and put out in honor of Rev Mosha Weinberger, who we’ve had many times on 18forty. And it’s set to this beautiful passuk in Yeshayhu. And the Passuk says: “For the mountains may move and the hills can be shaken but my loyalty will never stop, will never move from you, and my covenant will never be shaken, said God, who always takes us back with love.”

And this is the love, the love that’s created when both parties commit to one another, the love that is only created when two people come together, that covenantal love between Am Yisrael and God, between God and the Jewish people, that I think is what Pesach is all about. It’s when Judaism stopped being a collection of individuals of Avraham, Yitzchak and Yaakov and we took that foundational love and became a nation and created that Bris between Amcha Yisrael, the Jewish people, not a collective of individuals but a people, and Hakadosh Baruch Hu we became that Ezer Kinegdo, that helper alongside God in bringing that everlasting love to the world.

So, thank you so much for listening. This episode, like so many of our episodes, was edited by our dearest friend Dina Emerson, while she was on an airplane no less. It wouldn’t be a Jewish podcast without a little bit of Jewish guilt so if you enjoyed this episode or any of our episodes, please subscribe, rate, review, tell your friends about it.

You can also donate at 18forty.org/donate. It really helps us reach new listeners and continue putting out great content.

Thank you again to our incredible sponsors, Danny and Sarala Turkel. We so appreciate your continued support, kindness, generosity and encouragement.

You can also leave us a voicemail with feedback or questions that we may play on a future episode. That number is 917-720-5629. Again, that number is 917-720-5629.