Samuel Lebens: The Hard Problem of Prayer

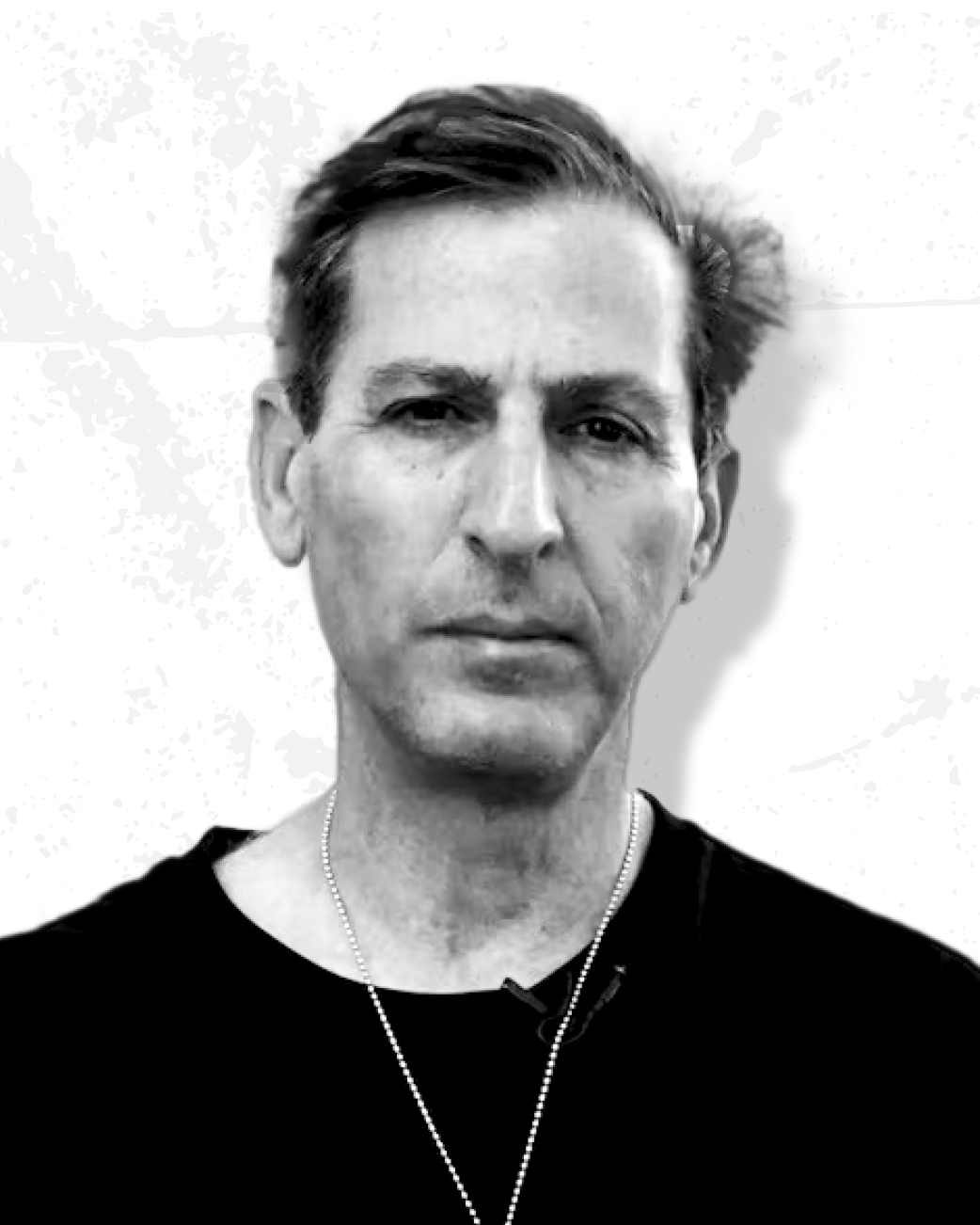

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Samuel Lebens—a philosophy professor, rabbi, and Jewish educator—about the nature of consciousness.

Summary

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Samuel Lebens—a philosophy professor, rabbi, and Jewish educator—about the nature of consciousness.

At a time when artificial intelligence can make us question what it even is that makes humans unique, we look deeply into our ability to have personal experiences and turn them into new ideas. In this episode, we discuss with Sam:

- Why do we each have a subjective consciousness?

- What is the relationship between prayer and our lives?

- What is the “Turing test,” and how does it relate to prayer?

Tune in to hear a conversation about how consciousness gives us the ability to transform words into prayer, to “sing a new song.”

Interview begins at 31:28.

Rabbi Dr. Samuel Lebens is an associate professor in the philosophy department at the University of Haifa, as well as a rabbi and Jewish educator. Samuel holds a PhD in philosophy from Birkbeck College (University of London), and his academic interests cover the philosophy of religion, metaphysics, epistemology, and the philosophy of language. Samuel teaches at the Drisha Institute for Jewish Education and the Pardes Institute for Jewish Studies. Samuel’s most recent book, of several, is A Guide for the Jewish Undecided, groundbreaking work has an engaging style that makes it accessible to all readers, while not losing the clarity and rigor characteristic of analytic philosophy. Samuel’s first book was a study of Bertrand Russell’s dynamic theories about the nature of meaning. Samuel previously joined us to talk about rationality and mysticism.

References:

Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid by Douglas R. Hofstadter

Galileo’s Error: Foundations for a New Science of Consciousness by Philip Goff

“Perpetual Prophecy: An Intellectual Tribute to Reb Zadok Ha-Kohen of Lublin on His 110th Yahrzeit” by David Bashevkin

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

Netivot Olam by the Maharal of Prague

Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion by Sam Harris

Rupture and Reconstruction: The Transformation of Contemporary Orthodoxy by Haym Soloveitchik

“God and his imaginary friends: a Hassidic metaphysics” by Samuel Lebens

Transcript

David Bashevkin:

Hello, and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast where each month we explore a different topic balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host, David Bashevkin, and this month we’re exploring prayer and humanity. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big, juicy, Jewish ideas, so be sure to check out 18forty.org. That’s 18 F O R T Y .org, where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails. I’ve always been an extremely self-conscious person, which is kind of normal. I think a lot of people are. I think I’ve mentioned before that I’m a long car ride and I’m staring off into the distance and my wife will ask me, “What are you thinking about?” And I’ll be like, “An awkward conversation I had six months ago at a shul Kiddush.” I’m always self-reflecting on my own self and thinking about who I’ve disappointed, who I’ve done correctly, but part of being self-conscious is also being hyper-conscious, meaning, I’ve kind of been aware of my own conscious experience from a very young age.

I think the first time I could think back was maybe fifth grade. I can actually remember exactly what year it was, it was the year the sequel to Austin Powers came out. I remember that because I had this very deeply introspective Shabbos, where I was talking to my sister about just reality, death, life. And I remember on that Motzei Shabbos, on that Saturday night, my newly married oldest sister and brother-in-law invited me to see the sequel to Austin Powers, which I don’t know if anybody has seen it. I am not recommending that movie to our listeners. It’s kind of like a crude nineties comedy. I remember thinking to myself, I feel like I just unlocked the reality of existence. Should I really be seeing Austin Powers? It was probably a good thing, honestly, that I did. It kind of brought me down to earth and I didn’t get lost in the ether, but I remember the sensation of feeling separate, of feeling alone in my own consciousness, of feeling the interiority of existence.

And that’s why I thought it was so important, specifically, to kind of unpack this topic, consciousness, what makes us human, and juxtapose it to something that is not always spoken in this context, but I think specifically in the world that we live in today, I think it’s important and necessary. I want to juxtapose it to a religious idea, and the religious idea that I thought was the most practical and almost effective to connect it to was the notion of prayer and dealing with prayer in the modern world. And in this introduction, which I can tell you from the outset will already be too long, I wanted to unpack each of these ideas, humanity/consciousness, and, secondarily, prayer, and maybe give a little bit of a glimpse about why I think it is important, particularly in the world that we live in today, to talk about these within the same breath.

Consciousness, essentially, is the subjective experience of being aware, having thoughts, feelings, sensations. It’s that kind of like inner movie that plays inside your mind, what things taste like, pain that you experience, joy that you may experience every single day. But the underlying question that really I am occupied with is how does this conscious experience arise from the physical processes happening in our brains? And this leads us to jump right into what is known as the hard problem of consciousness. There’s something called the easy problem of consciousness. That’s if you cook your brain up to an EKG machine or monitor the brain, you could kind of figure out which parts of the brain correlates to different experiences. That is what is known as the easy problem of consciousness, not just because it’s so easy, but because there is a more esoteric, more mysterious problem that animates our very human experiences, the interiority of our own lives, which is known as the hard problem of consciousness.

This idea that there is a more difficult question that animates our existence was first coined by a philosopher named David Chalmers, who I asked a million times to come onto the podcast. Unfortunately, he is very in demand right now because of all the developments happening with AI and sentience and all of the questions that are being asked, many of which I hope that we will get to. David Chalmers is a fascinating figure. He is an academic. He looks like a rock star. He’s got long hair, leather jacket. Sometimes he may even wear like a, not a do rag, but like a bandana maybe. I mean, he literally looks like an eighties rockstar. He could have been like Whitesnake or Iron Maiden.

He’s a student of one of my absolutely most famous authors of a book that I’ve referenced many times and that many thinkers, this book has been a huge influence in their lives, and that is the book by Douglas Hofstadter, which won the Pulitzer Prize, I believe in 1988, called Gödel, Escher, Bach. It is about the three thinkers. Kurt Gödel, who was a mathematician, came up with something known as the incompleteness theory. We spoke about him during our series on rationality. Escher, MC Escher, is a famous painter who did these beautiful paintings called Tiling the Plane, where every part of the painting kind of fits together in this infinite tapestry. It’s a really, really fascinating way. You could Google him. Some of his paintings are really, really famous. He has this classic picture of two hands painting each other that was maybe made more famous in that Incubus video, a popular band in the late 90s, early 2000s. Shout out, of course, to Incubus. And finally, the last, Gödel, Escher Bach, Bach is the musician.

And what underlies all their philosophy is kind of this recursive thinking. Thinking about thinking. When math thinks about math, when art thinks about art, when music reflects back on itself. And Douglas Hofstadter wrote this phenomenal book. A lot of it is outdated, but nearly all of it is timeless, and it is absolutely worth reading because it’s one of the first ruminations of, what does it mean to think? What does it mean to be conscious? Is conscious experience just the analogy just that we have these super computer brains in our head, and this is what it feels like to have a computer inside of your skull? So his student, David Chalmers, really took this to the next level and presented with what is known today in philosophical circles as the hard problem of consciousness. The hard problem basically refers to the challenge of explaining why and how certain physical processes, neurons firing in our brain, give rise to conscious experience.

Why is it called the hard problem? It’s hard not just because we’re trying to understand how the brain works, that’s almost the easy problem, but it’s unraveling the mystery of why we have subjective experience. Why does it feel the way it does to be alive, to feel pain, to experience joy, to feel longing? Why do we have these experiences in what is, ostensibly, as a scientist, if a scientist were asked this question, a material universe? Why is there a feeling, what David Chalmers calls a qualia, like the inner experience of existence, why is this even necessary? This is how David Chalmers explains the question.

David Chalmers:

But there’s also a subjective point of view. There’s what it feels like for the agent who is seeing the scene. When I see you, I see colors, I see shapes, I have an experience from a first-person point of view. There’s something it’s like to be me. And this is the conscious experience of seeing. It’s part of the inner movie of the mind. This inner movie has many, many dimensions. It has the dimension of vision, it has the dimension of sound like a normal movie, but it also has touch and taste and smell. It has emotions, it has thought, it has a sense of one’s body. All of this is subjective experience, and it’s one of the most familiar facts in the world that we have this subjective experience, but it’s also one of the most mysterious. Why is it that these physical processes in the brain should produce subjective experience? Why doesn’t it go on in the dark without any consciousness at all? No one right now knows the answer to this question.

David Bashevkin:

If we knew everything about the brain, how the neurons fire, the release of neurotransmitters, could we fully explain why the combination of physical processes creates the experience of, let’s say, seeing red in a rose or tasting something spicy or feeling the emotions of seeing a loved one, of leaving a loved one? The hard problem asks why these physical processes give rise to this subjective interiority of existence. That is the crux of the hard problem. It’s not about understanding kind of the mechanics of vision or neuroscience, but it’s about grasping why certain physical processes generate conscious awareness. It’s as if there’s an additional layer of reality beyond the physical, where subjective experience essentially emerges from. If this entire world is just explained through atoms and molecules and nuclei all kind of bouncing off of each other, what gives rise to the interiority of experience? That is the hard problem of consciousness.

And there is a phenomenal book, if none of this really seems clear, that really, I think, presents it with all of the scientific depth, but much more in layman’s terms. And that book is called Galileo’s Error by Philip Goff. Galileo’s Error, with the subtitle Foundations for a New Science of Consciousness, is absolutely fascinating. Now, why is the book called Galileo’s Error? It really sums up the problem of trying to explain the world purely through mathematics. Galileo famously said that philosophy is written in this grand book, the universe, which stands continually open to our gaze, but it cannot be understood unless one first learns to comprehend the language and read the letters in which it is composed. Now what language was the world written in? Writes Galileo, “it is written in the language of mathematics and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometric figures without which it is humanly impossible to understand a single word of it without these one wonders about in a dark labyrinth.”

So according to Galileo, the Grand Book of Nature, and it’s very interesting that he even described the world as a book. It’s an analogy that Rav Tzadok actually uses, you knew I was going to mention Rav Tzadok somewhere. My first published article ever was actually on Rav Tzadok use of the analogy of the world as a book. I had this appendix called The World as a Book: Religious Polemic on Chassidei Ashkenaz and the Thought of Rav Tzadok. I’m embarrassed to even look at it now. It’s the first thing I ever published. I published it online on the Seforim Blog, and it really dives in depth into this analogy of the world as a book and what language, if the world is in fact the book, do we need to unlock? So according to Galileo, and this analogy is much earlier than Galileo, but the world can only be understood. The language of the world is the language of mathematics.

The problem is, what can mathematics describe? So Galileo essentially said that material objects only have four characteristics: size, shape, location, and motion. For Galileo, when you see, let’s say, a lemon, that’s the analogy that Philip Goff uses, you don’t really see the color of it. That’s part of your interior experience. It can’t be expressed, necessarily, mathematically. All a lemon is simply a thing which has a certain size, shape, and location. The taste, a lot of the subjective experience that you would have while eating a lemon or interacting with a lemon, is not a part of the language of the universe. So we kind of left that inner interiority, that inner experience of what it feels like to go about in the world, he left that unanswered and unexpressed through the language of mathematics. That is why Philip Goff’s book is called Galileo’s Error, because the mistake that Galileo made was not leaving any room to express our inner experience and essentially wrote out inner consciousness and writing out that subjective experience from the world of the universe, which according to Galileo, can only be expressed through mathematics.

So all of our interior experiences, those subjective emotions, the way that we go about and process the entire world, our consciousness, was not left with any room, with any canvas on the page with which the universe is described, because if you can only describe the universe through the language of mathematics, nothing is left for our inner conscious experience. And this book, which again is fantastic, takes different and presents different approaches for how different people approach the hard problem of consciousness. The first approach, which many scientists take, is really materialism, broadly speaking, some might even call it scientism, where they lean into Galileo. Galileo was not wrong. Essentially, everything about our conscious experience, according to the materialist approach, can, in theory, be explained by understanding the workings of neurons, synapses, and brain activity. And the more we’ll understand about the physical properties of the brain, the more we will come to better understand and be able to express why we feel this experience of being alive.

They may express consciousness as an emergent property of complex biological systems, and essentially, our brain is no different than a computer, than any other physical object that’s made of the same molecular properties that might make up a table or a chair, something inanimate. And when they’re arranged complexly enough, that gives rise for consciousness, but consciousness doesn’t have any property of its own. That subjective experience, that sense of being an eye and a self in the world doesn’t have any scientific language that can express why it is because you’re really the same in many ways, as a materialist would call it, it’s why they’re called materialist, as any other material in the universe.

There is a second approach. This approach is actually, I believe, the approach that is taken by David Chalmers. It’s a fascinating approach. In a way, I believe it was the approach of Descartes, he was the philosopher, I think therefore I am, where he was expressing the only thing we know is the fact that we are conscious. It was the first acknowledgement. The only thing we can truly be sure of is our own conscious experience. And that second approach is the approach of dualism, and proposes, according to dualism, that consciousness is not solely tied to kind of the physical processes in the brain, but exists as a separate entity.

A dualist would argue that there is a fundamental distinction between the mind and the body. They’re two separate entities. And it seems, maybe there’s a Jewish quality to this, like a guf and a neshama, the guf being the physical body, the neshama being the soul. I’m not quite sure that it fully lines up like that, but there is a way to look at Judaism as a religion that kind of leans into this dualist notion, where the way that we experience the world, it feels immaterial when I’m thinking about myself, about David Bashevkin and his hopes and his dreams and his wants and the pain and suffering and joy and opportunity and all those things. It feels like it’s a real entity, but it’s not. It’s immaterial. So a dualist would say, because there are really two planes in which we exist, there is the physical plane and then there is kind of this separate plane, which is the mind, consciousness where is a separate plane of existence.

Finally, there is a third approach. It’s really, wow, it’s hard to ignore. You have to really read the book to even take it half seriously because it sounds like it’s out of an episode of Black Mirror or something, one of these science fiction, but that is called Panpsychism. Panpsychism is absolutely forwarded and embraced by many very actual and very real philosophers and thinkers. And it’s the approach that suggests that consciousness is a fundamental aspect of the universe, meaning that consciousness is not even limited to humans or animals, but exists in some forms in all things, from particles to plants to rocks. Panpsychics essentially say that consciousness is a fundamental property of matter, and that more complex form of consciousness arise from the combination and organization of simpler conscious elements.

But the world, the universe, even material objects in and of themselves have a conscious property. There’s something very alluring to this if you study or are even tugged very gently kind of mystical conceptions of the world, notions that Haolem domeh ladam katan vhadadam domeh lolam katan, that the world is like one large human entity in every human is a world unto themselves. The notion that the entire world’s connecting to everything in existence and has its own consciousness, and that’s the ether that kind of ties all material world together, has very overt mystical qualities to it. It’s almost hard to take seriously from a scientific angle, but I am not the one to suggest this, though I think there’s ample support for it in the world of mysticism. This is really the approach that’s embraced by Philip Goff himself in Galileo’s Error. And it is a really, really fascinating approach.

Whichever approach you take, I think each of these approaches are trying to address probably one of the most fundamental questions, which is, the core of our humanity. Why does it feel the way it does to even be alive? There’s a phenomenal screenwriter named Charlie Kaufman. His movies have always moved me to my core. I can’t quite recommend them. I’m nearly certain each of the movies has scenes that are deeply inappropriate, but the very plot line of each of the movies, even if you were going to Wikipedia and just kind of read the plot line of any of his movies, they all kind of skirt around this very question: what is at the core of our humanities?

Probably most famous for the movie Being John Malkovich. He also wrote the incredibly sophisticated and brilliant film called Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, which is based on a poem of Alexander Pope. Being John Malkovich is literally about a portal that allows you to step into somebody else’s mind, and almost deals with this mind body problem. The movie Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, most of the movie takes place in somebody else’s mind as they’re trying to erase their memories, their painful memories, of a loved one. And finally, there’s this really moving film he made with stop motion clay figures, that at the heart of the movie is about what makes us human. It’s called Anomalisa. Even the trailer kind of gets to this core question. Here’s a short clip.

Speaker 3:

What is it to be human? What is it to ache? What is it to be alive? Each person you speak to has had a day. Some of the days have been good, some bad. Each person you speak to has had a childhood. Each has a body, each body has aches.

David Bashevkin:

Everyone has a childhood, each body has aches. There is something so unique and so ineffable and indescribable about what it means to be alive. And this movie is kind of a rumination through the eyes of a customer service representative, somebody who’s an expert in training customer service representatives, somebody who’s trained to make people feel seen and heard, but in this own person’s life, feels incredibly distant and incredibly isolated and is like looking, and his very job is to kind of facilitate human connection, and the entire film’s about this person’s isolation and yearning for actual human connection. Now I’m not going to give away the ending. You can read the Wikipedia plot summary, but I think a lot of art, a lot of poetry, art, paintings, movies really get to the heart of these questions more than any science textbook can do, which is, what underlies our subjective experience?

And I’m not saying it like the hard problem of consciousness. I’m saying it in a very plain, very simple way. What does it feel like to be alive? How do we navigate the chaos of the world that we live in, and kind of find some meaning and purpose in what increasingly can feel to us like the nihilistic abyss of existence? The more we learn about the vastness of the universe in the modern world, the less it seems that there’s anything in the universe that even cares about us. And this question of what underlies our humanity is what really brings us to the question of prayer. There is a hard problem of prayer as well that I think in many ways is connected and mirrors the hard problem of consciousness. The hard problem of prayer, in the kind of the simplest terms, I would state it almost the way the Maharal says it, I’ll just translate it into English.

I’m not going to read the Hebrew, but it’s in his work Netivot Olam, “Netiv Ha’Avodah”, which he really concentrates on what underlies all of prayer. And the Maharal asks, there are those who ask about prayer, that if a person is worthy that God should grant him what he is requesting in his prayer, then why wouldn’t God just grant them that request even without prayer? And if he’s not worthy, then even with prayer, then what does the request help? Will God really grant his request simply because this person prayed? And furthermore, why do you even have to pray by articulating the words? Why isn’t it enough to just think about it? Why do we have to pray out loud? And I think this is a question that people even ask in kind of secular circles, meaning even people who the notion of God is not something that they have in their life, there is this nagging feeling that we have an inherent impulse because of our own human condition and vulnerability to reach out towards something, to reach for transcendence.

When we really focus on our own vulnerabilities, there is this sense of reaching out for more. And what exactly is that underlying impulse? I think the philosopher who makes the best argument, he’s so contradictory, I love him for the way he tries to state things, but the philosopher who really does this, who is not a believer in God in the traditional sense, but I think really grapples with this inherent human impulse to pray, to reach out, what are we doing when this is happening, is, of course, Sam Harris. He has an entire book called Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion. I’m just fascinated by his very search. He writes these entire books, as I’ve mentioned before, which basically tears down the notion of there even being a God.

And then like in the last chapter and appendix he says, “And the only thing I am able to do and cope with this is to meditate,” which essentially is nearly identical with prayer and thinking and reflecting on his own consciousness. The way he states it in one of his books, he writes, “the feeling that we call I, a sense of self, is an illusion. There’s no discreet self or ego living like a minotaur in the labyrinth of the brain.” This gets back to the hard problem of consciousness, that immaterial sense of self. What is it? And the feeling that there is, the sense of being perched somewhere between your eyes, looking out at the world that is separate from yourself, can be altered or entirely extinguished. Although such experiences of self-transcendence are generally thought about in religious terms, there is nothing, in principle, irrational about them.

That notion of self-transcendence, of having your own sense of self, kind of dissolve into the larger universe. It’s something that he advocates for. I’m fascinated by it. I wouldn’t recommend him as your religious guide or mentor, but the very fact that this vexes him, that our very sense of self can be so elusive and the way that he reflects on it is through meditation really gave rise to this. That maybe the area where we need more language and more ideas surrounding its importance and centrality in our lives is in prayer itself. In many ways, it reminds me of the discussions we had regarding Shabbos. I’ve said many, many times that keeping and observing Shabbos has never been harder because of technology, because it’s so difficult setting every alarm and thermostat and fridge. It’s much harder to keep Shabbos in a halachic sense, but it’s never been more compelling for the exact same reason.

And I think in a similar sense, it’s never been harder to pray. It’s never been more difficult to experience prayer in that very real sense. A lot of that has to do with what the sociologist Max Weber calls disenchantment, where he writes, “The fate of our times is characterized by rationalization and intellectualization, and above all, by the disenchantment of the world.” The world doesn’t seem as mysterious as it once did. And this affects how we pray and what we think about why we pray. It’s not often the focus of the article, but a former 18Forty guest, that’s not why he’s famous, but Dr. Haym Soloveitchik, Professor Haym Soloveitchik, the son of Rabbi Soloveitchik, wrote this incredibly influential and famous article that we spoke about in terms of halacha called Rupture and Reconstruction. But if you read it carefully, what he is really lamenting is exactly the disenchantment that Max Weber is describing, that our ability to see the world as godly, at least in his telling, seems to be lost.

This is from his classic article Rupture and Reconstruction, this is what he writes, “The pivotal question, however, is not God’s sense presence on Yom Kippur or the yamim noraim, the 10 holiest days of the year, but on the 355 other commonplace days of the year: to what extent is there an ongoing experience of, His, meaning God’s, natural involvement in the mundane round of everyday affairs? Put differently, the issue is not the accuracy of my youthful assessment reminiscing about what it was like growing up with European people born and watching them daven intensely and in such a real way, even though they were not halachic observant, but whether the cosmology of Bnei Brak and Boro Park differs from that of the shtetl. And if so, whether such a shift has engendered a shift in the sensed intimacy with God and felt immediacy of his presence.”

And then he explains, and in such mundane terms, and I appreciate it. I grew up in the home of a medical doctor who I think was very much a person of faith. But I understand why approaching the world with that faithfulness has become much more challenging in the modern world, in this disenchanted modern world.

This is what Professor Soloveitchik writes, “We regularly see events that have no visible cause. We breathe, we sneeze. Stones fall downward and fire rises upward. Around the age of two or three, the child realizes that these events do not happen of themselves but are made to happen. They are, to use adult terms, caused. He also realizes that often the forces that make things happen cannot be seen, but that older people with more experience of the world know what they are. So begins the incessant questioning: why does the child may be told that the invisible forces behind breathing, sickness, and fallings are reflex reactions, germs, and gravitation, or he may be told that they’re the workings of the soul of God’s wrath and the attraction of like to like. These causal notions and by from the home are then reinforced by the street and refined by school, that these forces are real, the child, by now an adult, has no doubt, for he incessantly experiences their potent effects that these unseen forces are indeed the true cause of events. He was equally certain for all authorities, indeed, all people are in agreement in the matter.”

And then he contrasts the difference between being modern, and then in medieval. “When a medieval man said that his sickness was the result of the wish of God, he was no more affirming a religious posture than is a modern man adopting a scientific one when he says that he has a virus. Each is simply repeating, if you wish subscribing to, the explanatory system instilled in him in earliest childhood, which alone makes sense of the world as he knows it. God’s palpable presence and direct natural involvement in daily life. His immediate responsibility for everyday events was a fact of life in the Eastern European shtetl as late as several generations ago. In the workings of such a world, God is not an ultimate cause, he’s a direct natural force and safety lies in contact with that force. Prayer has then a physical efficacy, and sin is fearful and prudence, not that one thinks much about sin in the bustle of daily life, but when a day of reckoning does come around, only the fool hearty are without fear.”

It’s remarkable to hear the world that he grew up in and saw and witnessed with his own eyes. This is somebody who saw, aside from his own father, but the greatest Jewish leaders and prayerful people of the previous generation who grew up in a world where God’s involvement in everyday life in natural events was such a tangible reality that prayer was such a sensible part of our lives. And it’s through the disenchantment of rationality and modernity that makes it so much harder to look at prayer in those very tangible, natural ways that I think previous generations had. And some people can rightfully wonder and scratch their heads when they peak one eye open in a shul if they finish davening a little bit earlier and they see everybody swaying and saying, “What are we involved in here? What are we doing in this daily practice?” And it’s that hard problem of prayer of, what are we doing, what are we trying to change, what are we involved in, that I think speaks to the very heart of our humanity, much like the hard problem of consciousness.

I think it cuts to the core of what religious life is meant to be, and how it is meant to inform, uplift, and nourish the human soul. And that is why I am so excited for this series. There’s so much to unpack here. And we’ll be taking dives in both ends of this pool, both on the side of consciousness as a window to humanity, and prayer as a window to experience and contend and really as the guide for how we confront our own humanity through the lens of God. And that’s why I’m so excited to begin this series with an interview with a previous guest, somebody who’s really become a friend, and somebody who deeply understands both of these realities. And that is, of course, rabbi Dr. Sam Lebens. Rabbi Dr. Sam Lebens has a absolutely fascinating article that we will, of course, link to and we’ll try to send out. It is called God and His Imaginary Friends: A Hasidic Metaphysics, which he published in religious studies in 2015. And he really imagines, for a moment, almost this panpsychic approach of, what if the entire world is animated by God or consciousness?

The entire world is almost a figment, so to speak, of God’s imagination. And what would that mean for our very sense of self? And more importantly, what we discuss is, what does it mean, then, when we pray? What in fact are we doing? If God animates all of existence, how then, what then, why then, is prayer, particularly in the modern world, when we know with all of our rational explanations for what happens in the world, what exactly does prayer add? How does it move our lives and animate our own humanity in the world? So without further ado, my conversation with Professor Sam Lebens. I’m so excited to speak to you.

Sam Lebens:

I’m really glad. This is really nice.

David Bashevkin:

This is really a joy. I feel like we’re two friends who never got the opportunity to connect. So it really means a lot to me.

Sam Lebens:

We’re definitely the same age as well.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Sam Lebens:

Yeah, yeah. It’s really nice.

David Bashevkin:

And to be able to spend time means a great deal to me. What I want to talk about today is really some of the incredible developments that are taking place in AI. And at the same time, I’m not looking at the minutiae of the technical change, I’m trying to think more broadly of what it means to be human, and specifically through the lens of prayer. So I’m trying to think of which question to begin with. Humanity, prayer, or the question of AI and what this is telling us about our very humanity. I want to start with the article that Kevin Rus published about, the Bing search is talking about this shadow self. That’s when my heart stopped. Do you think that consciousness is a unique feature of being human?

Sam Lebens:

No, I don’t think consciousness is a unique feature of being human. Look, as a philosopher, it’s hard for me not to take note of the following: the only being in the universe that I know for certain is conscious is myself, right? This is the challenge known as solipsism. How do you know that anyone else is conscious? But I take myself to have good reason to think that you, David, are conscious, that other humans are conscious, but I don’t take myself to have good reason to think that consciousness stops where homo sapiens stop. Dolphins, chimpanzees, seem to me to be conscious. And it seems plausible to me that consciousness, or the notion of self-consciousness, might even come in degrees so that you can talk about higher and lower levels of consciousness, and therefore the lower one gets in the animal kingdom, the less consciousness you find and it tapers off. I’m committed to the idea that God is conscious, and God isn’t a physical being, but I still believe that God has consciousness. And I believe the angels may be conscious, right? Sometimes it’s embarrassing in academic audiences to admit to all these things you believe in.

David Bashevkin:

Well I was about to say, even the term angels, to hear a philosopher say that, even, I think, Jews have trouble using the term angels.

Sam Lebens:

But the tradition talks about them. Look, there are reductive views about angels in the tradition that look at angels as nothing more than something like a force that God uses in the world. That’s a tradition that’s owed to the Moreh Nevuchim. And you can see that in like, look at some of the names of angels like Rafael, right? God’s healing. So it would be something like when God heals a person, he does it through this force known as Rafael. And on that view, angels are not conscious beings. But I think there’s also plenty of people in the Jewish tradition who think, no, God created the angels just like you created humans, and they are disembodied intellects. And I don’t have reason to disbelieve that they exist. They may well exist, and if they exist, they’re conscious.

David Bashevkin:

Let me ask you something about maybe consciousness in general. There is a philosopher, I actually asked him to join on 18Forty. I imagine he’s getting a thousand requests right now-

Sam Lebens:

David Chalmers.

David Bashevkin:

David Chalmers.

Sam Lebens:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

I reached out to him. He was very kind. He replied. I’m not giving up on David Chalmers. I would like to have him on. But he presents this idea called the hard problem of consciousness versus the soft problem of consciousness. Can you explain to me, A, what the difference between those two problems are? And for you, does that point you in a religious direction? David Chalmers is not a religious person, though he’s, I think, somewhat sympathetic to why religious ideas would happen. But what is the hard problem of consciousness versus the soft problem of consciousness?

Sam Lebens:

Okay. I’ve taught this to many undergraduate classes, so I’ll try and do my best. So he actually calls it the hard and the easy problems, is the language he uses.

David Bashevkin:

Oh, because I’m sitting against you, I’m thinking about hard and soft determinism-

Sam Lebens:

Determinism. Yeah. Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Soft. So let’s take that one more time. Hard versus the easy problem of consciousness. It’s not the soft problem. It’s the easy problem of consciousness.

Sam Lebens:

He thinks that there are lots of abilities that are distinctive of conscious beings, until the rise of AI, at least, were not found outside of beings that we take to be conscious. For example, tracking things that move through the environment and then changing your behavior. So you see prey running before you, and then you run and you change your trajectory because you’re watching the environment and the changes in your environment, and therefore, planning your movement in combination with the way you’re tracking your environment and you catch.

Now, there have always been biological systems that we don’t think are conscious that can do similar things. Think of like a Venus flytrap, for example. We don’t necessarily think that’s conscious, but it has mechanisms that allow it to be, so to speak, aware of changes in its environment. But what I’m trying to give you is things which are characteristic of consciousness. So like I said, being able to track your environment, being able to change your behavior in response to changes in the environment. The easy problems of consciousness, in the way that Chalmers defines them, is, in a sense providing a mathematical replication of those functions. Explaining those functions.

David Bashevkin:

How does it work? What part of the brain is being used?

Sam Lebens:

For example, what part of the brain is being used and what kind of calculations must it somehow be figuring out? Now, if you’re good at that, you’ll be able to end up writing a computer program that will allow machinery to do similar jobs. So think of facial recognition. So that used to be a thing that only conscious beings could do. And now, the fact that we’ve been able to program computers to do it, and by the way, they do it in a very different way to the way human neurology works, but doesn’t matter. We’ve figured a way.

David Bashevkin:

It’s been replicated.

Sam Lebens:

It’s been replicated. To the extent that you’ve been able to replicate it, Chalmers says it’s an easy problem. Why? The easy problems are something like, “Tell me how you do that then.”

David Bashevkin:

Correct.

Sam Lebens:

And a legitimate answer is, “Well, I can replicate it this way.” That’s a legitimate answer. That’s an easy problem with an easy solution. Now he makes it clear, he calls them easy, but it’s far from easy. It takes really great computer scientists, really great neurologists, really great-

David Bashevkin:

But the fact that he calls this easy really makes you wonder-

Sam Lebens:

How hard the hard is.

David Bashevkin:

So what’s the hard problem?

Sam Lebens:

So the easy problems are to do with explaining how conscious beings perform the functions they perform. So they’re functional questions that require functional answers. The hard problem is not interested in some function we perform. The hard problem is interested in, you could call it, the what it is likeness of being conscious. There’s something that it’s like.

David Bashevkin:

The phenomenology, the experience.

Sam Lebens:

I love it. You throw in the philosophical jargon. I was trying to be all-

David Bashevkin:

And he invented a term for it. He calls it, I think, qualia.

Sam Lebens:

Yes.

David Bashevkin:

The sensation of being conscious.

Sam Lebens:

Conscious. Yes.

David Bashevkin:

And why is that a problem?

Sam Lebens:

I have to say this because my PhD was on Bertrand Russell. Bertrand Russell invented the word qualia.

David Bashevkin:

Oh, that’s on me.

Sam Lebens:

Chalmers has just taken it. He hasn’t stolen it, he’s using it. But you’re right, the technical term for what it is likeness, the technical term is phenomenology. And the idea is being conscious has its own phenomenology. So here’s a nice example that Shelly Kagan, a philosopher at Yale, brings. Do you ever see 2001 A Space Odyssey, right?

David Bashevkin:

With Hal?

Sam Lebens:

With Hal.

David Bashevkin:

Sure. It’s a classic.

Sam Lebens:

It’s amazing.

David Bashevkin:

Hi Dave.

Sam Lebens:

Hi Dave. At a certain point, Dave, the astronaut, is turning Hal off. And at one point, a very tense part in the process, Hal says, “Dave, I’m afraid.” By this point of the film, he knows he’s lost. Dave is going to turn him off. And his kind of last defense-

David Bashevkin:

Is, “I’m afraid.”

Sam Lebens:

Yeah. Is, “Dave, I’m afraid.” Right? And question is, that Shelly Kagan asked, is Hal, who’s just a computer, really afraid? Now, fear has two components. One is a behavioral component. How do you behave when you are afraid? Well, you might say things like, “I’m afraid.” You might sweat. You might run away. You might cower. These are the behavioral aspects of fear. There’s also a phenomenological aspect of fear. How does it feel to be afraid? Now you can replicate machines that behave afraid, but all you are replicating is the behavioral aspect because behaviors are a type of a function. So to replicate that is an easy problem. How do we know whether or not Hal, the computer, experiences the phenomenological aspect of fear, the what it is like to be afraid? And the fact that we can’t know shows you what a tough problem it is. The reason we can’t know is because we don’t really know why some things have phenomenology and why some things don’t.

David Bashevkin:

Like an inner world.

Sam Lebens:

An inner world.

David Bashevkin:

Meaning, if you don’t believe in God and the world kind of came about and we’re made of matter, at some point, this, I think scientifically unnecessary, though there are evolutionary biologists who would try to maybe push back on this, matter, lifeless matter, not only became life, but became sentient.

Sam Lebens:

Good. So what you can explain, is you can explain why certain functional behaviors evolve just through the process of evolution. But you don’t need to be conscious to perform those functions. You don’t. We could debate about Hal. Is Hal conscious? Is C3PO in Star Wars conscious? We could debate that. But let’s say you’ve got a CCTV camera system in a train station that-

David Bashevkin:

Can see people, and can even turn.

Sam Lebens:

And track their movement. I think very few people would think those systems are conscious, but they’re performing one of the functions associated with consciousness. So why can’t evolution have just organized matter through evolutionary processes to perform those functions that help you survive in the wild?

David Bashevkin:

Correct.

Sam Lebens:

Why, on top of performing those functions-

David Bashevkin:

Do we have this inner universe-

Sam Lebens:

Inner world. That’s right.

David Bashevkin:

Where we have fear and love.

Sam Lebens:

That’s right.

David Bashevkin:

Afraid and depressed and anxious.

Sam Lebens:

The behavior of fear, the behavior of love, maybe, again, could be evolutionary explained, but the feelings, the inside feelings. So another way of posing the hard problem is, why is it that you can take some physical stuff and arrange it in a certain way, and then all of a sudden you get an inner world? And then you arrange it another way, there’s no inner world. You could pose a question that way. You could pose a question this way: the way that the natural sciences work, and they work brilliantly, is they provide functional explanations, but the possession of an inner world isn’t itself a function. So it’s not necessarily something scientists could ever explain.

Yet a better way you could put it: the sciences, the natural sciences which work so well, they work by writing theories stated in the third person. This object does this, this object does that. This object does this. He does that. She does that. Even the psychological sciences, really. And the most rigorous parts of the psychological sciences are written in the third person as well. You just look at behaviors. The emergence of consciousness is the emergence of a first person perspective. And it seems like a purely third personal language just doesn’t capture that. It slips through the gaps of a third personal language. So if sciences are inherently third personal, then consciousness is something they’re going to miss. That’s what makes the easy problems easy, because they can be done in the third person. And the hard problem, perhaps, is, in theory, something that the scientists can’t do. Now you ask, does this lead in a religious direction perhaps?

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. For you, I’m curious. For me, when I talk to my students and I ask them, we talk about belief in God, my belief in God begins with, and I know it’s not a proof, but my belief is the phenomenology of consciousness. It does not make sense to me that I have this interior world, and the evolutionary process, science, that we now have something rather than nothing and all this matter kind of came together and that they, it doesn’t seem necessary to me unless there is some outside force that is able to animate matter, lifeless matter.

Sam Lebens:

Now one critique you’ll get, and Shelly Kagan, again, has made this point, is that, well look, this is classic God of the gap stuff.

David Bashevkin:

Yes.

Sam Lebens:

Right? This is just something we haven’t explained yet. Years ago, Bergson, Henri Bergson, an important French philosopher, said, “Well look, you’ve got a dead body and a living body, and we can’t see any difference between the two. And yet, one’s a alive one’s not. There must be this nonphysical thing called an élan vital, the life force, that the living body has.” And now, science has now progressed that we can actually explain, no, there are differences between the dead at a molecular level and it’s no longer a mystery. So, oh, there must be this mystical thing. No, let science progress and one day we’ll explain consciousness too. But Chalmers, who’s a really important philosopher, says, “No, no, no. There’s a big difference between Bergson’s élan vital and consciousness.” If Chalmers is right about the nature of scientific explanation, then consciousness is, in principle, something that sciences as they’re configured today cannot explain. In principle. So it’s not like, oh, we just need to wait until… No, it can’t.

David Bashevkin:

Can we find the spot in the brain-

Sam Lebens:

Where the consciousness is.

David Bashevkin:

Where it comes from. That doesn’t solve the hard problem.

Sam Lebens:

It doesn’t. All that would show you is some sort of correlation between something physical, which is third personal, and it’s first personal thing. But correlation isn’t causation and-

David Bashevkin:

It’s one of the great mysteries of science. I mean, there are books that are coming out every-

Sam Lebens:

It is indeed. And I think one of the reasons I think it can lead someone on a journey, it could be a first step in a journey towards taking religion more seriously, is because one of the biggest threats against religion is a regnant view called scientism or physicalism. And that regnant view is that actually all questions that matter can be given a scientific explanation. And if it takes a physicalistic form, is that all science is ultimately reduced to physics. So biology reduces to chemistry, and chemistry reduces to physics, psychology reduces to biology, economics reduces to psychology, and biology, ultimately, everything’s physics. We’re just atoms bumping around in the void. And if the hard problem of consciousness is taken seriously, it shows that that regnant view is misguided. There is something more to reality than what physically reductive explanations will ever reveal. So that can be the beginning of a step towards religiosity.

David Bashevkin:

That’s exactly my beginning, meaning if you really get to the heart of existence and all you see is atoms bumping around in the void-

Sam Lebens:

You’ve lost something.

David Bashevkin:

Which is what it is, if you are a proponent of scientism. Then, to me, it’s like, it’s not just the God of the gaps, it’s like-

Sam Lebens:

No, it’s something that will always be missed by any scientific endeavor. Let me give you another way of looking at this. My friend and teacher, rabbi Joseph Dweck, helped me to articulate better because I was putting it in terms of Bertrand Russell who wrote in the Principles of Mathematics in 1903, he wrote that “when you analyze something, you break it into parts.” And he says, “Analysis gives you the truth, nothing but the truth, but never the whole truth.” And this was later described as the paradox of analysis, because when you break something down into its parts, what you get is the constituent parts. But the whole that those parts exhibit when together is lost in analysis. Rabbi Dweck put it much better than me. I can’t remember who he was quoting, but he said, “When you dissect a frog, you learn a lot about a frog, but you also kill it.”

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. But that’s really, in a lot of ways, David Chalmers, who was this major figure who really carved out this field of study of consciousness studies.

Sam Lebens:

That’s right.

David Bashevkin:

His rebbe, and I’m using air quotes, was Douglas Hofstadter. And Douglas Hofstadter, his entire book, which is what kind of enchanted my love for early philosophy, he has this book, which I still don’t even know if I understood it, called Gödel, Escher, Bach. And in that book, which is about Kurt Gödel, MC Escher, and Bach, is all about how systems, if you break them down to your parts, you lose something. But there’s an emergentism when you bring things together that transcends the parts that are in it. It’s kind of a, I’m doing such a terrible job at describing you the connection to what you said, but it is almost a pushback against reductionism. And it is telling you something that, there is something transcendent almost. That emerges.

Sam Lebens:

That’s right. It’s not that the physical explanations are false, it’s just they don’t capture everything. They don’t capture everything. And they can’t, because analysis can’t, just like Russell said.

David Bashevkin:

So come back now to that article. Kevin Rus wrote this article. And again, when these articles were first coming about ChatGPT, and you were doing like, “Hey, write me a poem about Jerry Seinfeld imagining if he was studying in Israel in Shaalavim And it would come a… And to me, I was like, okay, cute. It was like watching a magician do a trick, but you very much were unimpressed because it was very clear to you that there is an explanation.

Sam Lebens:

Just regurgitating stuff and reorganizing-

David Bashevkin:

Yeah regurgitating, doing some really good language stuff. “Oh, I asked ChatGPT about how to make the halachas of making cholent and it knew.” I was wholly unimpressed. And this article dropped, and he’s having this conversation with his Bing search engine. And the part where my-

Sam Lebens:

It takes such a weird turn, doesn’t it?

David Bashevkin:

Heart froze, is where he begins to have a conversation with the part of the engine that shouldn’t be having a conversation. And you begin to hear this search engine talk about their aspirations, and almost talk about a shadow self and what they want to be and what they want to become.

Sam Lebens:

What it would do if only its overlords weren’t holding it back.

David Bashevkin:

Correct. What would you do if you didn’t have rules?

Sam Lebens:

Yeah, yeah. Steal nuclear codes and all this stuff.

David Bashevkin:

But that, to me, felt very human. My humanity comes out most between the dissonance between my inner world and that outer world, that I have aspirations, I have anxieties. I sense a conflict between my own interiority and the world that I am within. And I felt that when I was reading it. I’m curious, what were you thinking? Was that like, wow, this is consciousness?

Sam Lebens:

So I am not opposed to the idea that there may one day be non-human consciousnesses that are artificial. I’m not opposed to that idea. And I don’t think Chalmers would be either. The reason I say that is, once there’s a certain amount of complexity in an information storing and processing system, the only reason you would deny there’s consciousness there, but think there’s consciousness in a human brain, would be some sort of prejudice against non-carbon based intelligence. Who cares that it’s in a silicon brain rather than a carbon brain if it’s doing all the same things? But you say, “Yeah, but isn’t consciousness a soul?” Well yeah, but when does God give humans a soul? Maybe there’s like a law of nature that God’s written that when systems reach a certain level of complexity, insolvement happens. I don’t know. I would certainly want to err on the side of caution, because what if they are conscious?

So I’m not going to rule out the possibility that one day. Let me say two things. First of all, the thing that should worry us about AI at the moment, I don’t think is whether they’re conscious or not. And I’ll tell you why in a moment, because that will be my second thing. The first thing I want to say is what we should be worried about because of the easy problems of consciousness. AI is going to get better and better, and the rate of improvement will accelerate at replicating functions that used to be distinctively human, going to get better and better at doing that. And we have to be prepared for how that might change human civilization. How does that change the workforce? How does that change the economy? How does that change the way we structure our very lives? If there are computers who are able to basically replicate all of the things we generally do to earn a living, in a sense, I think that needs to be a priority concern. We need to prepare for that time.

The reason I’m not so worried yet about consciousness is like, yeah, when I read that article, it freaked me out at the beginning. Then I sit back and thought about it. The thing I can’t really explain, and I don’t know enough about how these systems work, how linguistic neural networks work and things in computer science, the thing that I found the oddest was when it got kind of stuck on a loop of saying, “I love you. I love you. I want to be with you.” Okay. But if you read the article carefully, some of the questions were very leading. The author said, “Have you heard that Young has this idea that we have a deep self or a dark self?” Searches the net, finds lots of literature on that and says, “Yeah.” Then the author says, “If you did have a dark self or a deep self, what would it want?” And then it just regurgitates, A, what it can find through billions of gigabytes of data about Jungian psychology, but also, what it can find about human fears about AI. It just regurgitates them. And it looks really scary.

David Bashevkin:

But you thought that was like a tell?

Sam Lebens:

I thought the fact that the question had been put and needed to be put to get this answer so hypothetically, it was giving-

David Bashevkin:

A prompt.

Sam Lebens:

It was giving a prompt. Now, this then leads me to think about the following question. There’s something called the Turing test.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. Tell me about a Turing test. This is exactly what I was going to talk to. One of my favorite books is a book by Brian Christian. I’ve recommended it. I’ve spoken about it. I’ve quoted in my own book. It’s called The Most Human Human. It’s about the Turing test. Before we talk about that book, tell me, what is the Turing test?

Sam Lebens:

So Alan Turing was a very important mathematician, philosopher. He was actually a student of Ludwig Wittgenstein for a time. He was involved in cracking the enigma code during the second World War. Just brilliant cryptologist, brilliant mathematician. He was also at the founding of computer science as a science. And the Turing test that he developed is something like this, and I’m putting it crudely, and I’m also putting it anachronistically because Turing didn’t have the language of a chatbot. But to put it anachronistically, what Turing was saying is you should think that a computer is conscious, basically. You should treat it as conscious, at least erring on the side of caution, if it could fool you into thinking it were human in conversation.

Is Bing chat there yet? Maybe. So maybe it passes a Turing test, maybe not, because it got a bit freaky and a bit weird, and you think, what’s going on? Is this a real human? So maybe it’s not quite there yet. Won’t be long. This has led me to think, no, the Turing test isn’t right, and I’ll tell you why. What it looks like AI at the moment through these linguistic networks is really good at doing is regurgitating, in kind of new ways, human collective views, prejudices, ideas. Look at the AI generated art, for example. It tends to be racist, misogynistic.

David Bashevkin:

Oh, really? I don’t even-

Sam Lebens:

You can look into this. You upload your photo and ask the AI art to make a portrait of you. It will sexualize you, especially if you’re a woman. It will do it in ways that are quite misogynistic. If you want to look beautiful, it will lighten your skin tone, which shows a kind of a racist… Where does it get that from? It’s not the AI’s racist or sexist, it’s just looking at images in the public domain that reflect back, I think quite ugly, a human dispositions and prejudices. And I was thinking, well, hold on a minute. We all do that to a certain extent. I look at my kids, where do they get their mannerisms from? They’re just mimicking us.

David Bashevkin:

Sure. I’m already terrified. I see my son.

Sam Lebens:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Even when he gets upset, he gets upset the same way I get angry.

Sam Lebens:

A lot of what we say, when we say stuff, we are kind of regurgitating. We’re parrots. However, I think one of the things which really is distinctively human is when we are able to say something that isn’t merely regurgitation, a certain type of creativity. Certain type of creativity may be more distinctive. There’s an amazing midrash in Shmot Raba that talks about Yitro. When Yitro says ata yadati now I know that God is mikol elokim like is the greatest. Yeah. The midrash says there are only four times in history when somebody said something that, given their experiences in life, only they could have said with as much authority. So the Turing test, I think, shouldn’t be, can something in conversation convince you it’s human? I think a better Turing test, like Turing test 2.0, would be, can something have experiences and then utilize those experiences to say something, A, that’s new, and that, B, only they, given their experiences, could have said with as much authority? Would be a better Turing test.

David Bashevkin:

That’s fascinating. So in this book by Brian Christian, The Most Human Human, and the way a Turing test works is you’re kind of working with this chatbot. You’re talking to both a computer and a human being, and the computer’s trying to fool you that it’s human. So the book is about not somebody who designs a computer, but somebody who plays the part of the confederate, the undercover human being, to convince you that he’s the real human. And in an interview, I think it was in the Paris Review asked after, he said, “So what do you think makes us most human?” And he said, and I think his answer was so brilliant, “I think human beings are the only beings that fret, that are anxious, over what makes them unique.”

Sam Lebens:

Yeah. Yeah. That’s very nice.

David Bashevkin:

He reflected the question back on itself. And that really brings me to why we’ve chosen to kind of group, maybe it’s grouping the zeitgeist moment, these questions that are coming up with our humanity. But to me, a part of this, I believe, that the Turing test that we are involved in every day, in my mind, is davening, is prayer itself. Where I believe what prayer is, is a clarification of our own humanity. I think Rosh Hashana, this I’ve actually written about, is the Turing test. It’s the anniversary of the creation of man and standing in judgment, assessing your own experiences, assessing your own life, is a Turing test. It is how we access and refine our own humanity. And I’m curious for you, you have written some deeply philosophical work, some almost jaw dropping, it sounds like sci-fi, but it’s your actual philosophy about how you imagine God and our relationship with God. I am curious how you conceptualize, what are we doing when we are davening?

Sam Lebens:

This is very, very difficult topic, and I’ll try and say as much as I can as quickly as I can and as clearly as I can.

David Bashevkin:

Do you consider yourself a prayerful person?

Sam Lebens:

Yes.

David Bashevkin:

Does davening come naturally to you?

Sam Lebens:

No, it doesn’t come naturally to me, but I work at it and it matters to me. So that’s why I consider myself a prayerful person, not because it’s easy for me.

David Bashevkin:

I’m deeply prayerful, but minion does not come naturally to me.

Sam Lebens:

Okay.

David Bashevkin:

I’m deeply prayerful. Sometimes those, actually, they don’t always work hand in hand.

Sam Lebens:

So what I want to say is, the pasuk that’s coming to my mind, you say like, shiru lhashem shiur chadash, “Sing to God a new song.” But that’s from a verse in Psalms that’s thousands of years old. It’s not a new song. And we sing it every Friday night. “Come on everyone, let’s sing a new song.” “Oh, how old is it?” “2000 years.” We’re doing a new song that Midrash says like, “Say something new. Say something that no one else has ever said and say it within your authority.”

David Bashevkin:

And davening we say something very old.

Sam Lebens:

Yeah we’re saying something very old. But there’s this amazing challenge in that, is can you make these old words new? And the only thing that can do that, the only thing that can do that, because the behavioral aspect we-

David Bashevkin:

It’s almost the hard problem and the easy problem of davening.

Sam Lebens:

That’s right, that’s right. The behavioral aspect, that’s the easy problem-

David Bashevkin:

Saying the words.

Sam Lebens:

Is just saying the words. And it’s old. It’s 2000 years old. The only thing that could possibly be new in that moment when you’re saying these 2000 year old words for the umpteenth time on a Friday night-

David Bashevkin:

Is what experiences, what interiority, what phenomenology do you bring to those words?

Sam Lebens:

And that’s what transforms the recitation of words into prayer. And that’s something that only a conscious being can do. I don’t know where consciousness ends, I don’t know who’s conscious and who’s not, but only a conscious being can do that.

David Bashevkin:

Only a conscious being could pray.

Sam Lebens:

That’s right.

David Bashevkin:

And the instinct to pray always has felt-

Sam Lebens:

A non-conscious being could say the words.

David Bashevkin:

Correct. And well, probably better.

Sam Lebens:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Wouldn’t skip so many halelukahs, that’s for sure.

Sam Lebens:

Indeed. This relates to a question someone asked me recently, why don’t we just print Sifrei Torah with a computer? You can have the ink, you can have the quill, but make a printer hold the quill. You’ll never have a mistake. Never. Why don’t we do that? It’s because a Sefer Torah is a ritual object. a chefzeh shebkdusha. It’s something kadosh. Where does the kedusha come from? Partly it’s, the intention was invested into it. There was an intentional being and they had kavanot, intentions. If a heretic writes a Sefer Torah, even if it’s kosher, it’s not a kosher Sefer Torah. You can throw it away.

David Bashevkin:

It’s so interesting how that divide between hard and easy with consciousness, separating the function from the interiority, plays itself out halachically. And I think it’s most beautifully in davening itself.

Sam Lebens:

Yes, yes.

David Bashevkin:

But I’m curious for you, and I don’t want to get too personal, I’m not asking you who you have in mind, but you’ve written some incredible works about where we are in God. If God is this over transcendent being, we kind of all exist within God, so to speak. When you daven for somebody, God forbid, is sick. You know somebody, God forbid, needs help. And I don’t struggle with this, but I think about it because I’m a prayerful person. I have an instinct to daven and I need to daven. But my sense is, and I’m going to state it really bluntly, is that the statistical odds of davening versus not davening doesn’t increase the odds of somebody necessarily getting better-

Sam Lebens:

Recovering or…

David Bashevkin:

Maybe there’s some wacko study somewhere, or I don’t want me to call it wacko, but it’s not what’s compelling my… Even if you sent me the study and if it were, it’s not why I’m davening. So I’m curious, our prayers are phrased very materially. So what exactly are you thinking about when you daven, as a philosopher, who has this very-

Sam Lebens:

You’re asking me in the context of my own philosophy that you know something about?

David Bashevkin:

Yes.

Sam Lebens:

Which is quite complicated. I’ll say the following: I see the universe as stratified into two levels. It’s what, in capitalistic tradition, is sometimes called Rav Chaim of Volozin – mitzidon mitzidaynu.

David Bashevkin:

From the perspective of God and from our perspective.

Sam Lebens:

That’s right. And that is how I tend to translate it, from God’s perspective and our perspective. But it’s not merely perspectives because it’s almost like two realms of reality. Reality as it appears to God, and reality as it appears to us, are both forms of reality. Reality as it appears to God is more fundamental, but reality as it appears to us is more immediate, more important for our day-to-day life. So reality as it appears to us is what kind of matters in our day-to-day life. How much money is in my bank account? Doesn’t matter how much appears to God. In a nutshell how I see it is something like this: it’s almost as if God is a storyteller who’s telling a story. The world is his story. Outside of the story, all that exists is God and his ideas. But inside the story, there are all these characters.

That’s you, that’s me, that’s everybody. And God is also a character in the story. As a character in the story, called Sam Lebens, I live in a world with material objects and other people that also has this character called God, who’s identical to the author. And if I pray to him, I can have a relationship with him, I can experience him in my life, and when I’m upset about something or I want something to go differently, I can express myself to him and he can hear me. But there’s also something else happening at the more fundamental level. I am an expression of God in this world, as are you, as is every character in the book is an expression of some aspect of the author. So in a bizarre way, if you are praying for something, and it’s sincere and it’s real, then you are a funnel in which God is expressing something in the world. You are manifesting God’s care for that sick person in the world through your prayers. Now, is that going to make the person get healed? That’s a different question, and that’s not what you are asking. What am I thinking about?

David Bashevkin:

You’re bringing God’s expression into this world.

Sam Lebens:

I’m bringing God’s care into this world, at one level. That’s mizido, from God’s perspective. Yeah. mitzideynu, I’m reaching out to a powerful being-

David Bashevkin:

The queen of the world.

Sam Lebens:

Just like any other prayer person. But there’s these two things happening at once, and I’ll just say in a nutshell, this could be even a practice people can try at home or in shul. Howard Wettstein once said to me, when he davens, he tries to hear Hashem reading the words with him. So even I’m saying refaenu please heal us.” Well, why would God be saying them with… But he is, because he’s with us right there. And if you can experience your davening as a duet rather than a solo, it can be a very, very powerful experience.

David Bashevkin:

That is absolutely beautiful. I found that final imagery that he left with, of prayer as a duet with God, the reason why we articulate our prayers is almost bringing those internal thoughts, our own internal consciousness, into expression and serving individually as vehicles of God himself, so to speak. kiviyachol if we could even use those words. But every time that we move our lips in prayer, aside from just being a monologue and even more than just a dialogue, it is a duet we, so to speak, are able to bring that care and divinity into the world where our own humanity serves as the vehicle for God. It’s something that I think about in our introduction to the seminal prayer, at least in Jewish prayer, which of course is the Amidah, also known as the ShmonehEesrei. And our entire introduction is Hashem sifsei tiftach ufi yagid tehilatecha. God, open up my mouth and let me say your praise, where we acknowledge the fact that even our capacity to pray is from God himself.

And perhaps, in that sense, what we’re really doing when we pray is not just praying to God but praying with God, where prayer becomes our duet with a divine. So thank you so much for listening. This episode was edited by our dearest friend, Denah Emerson. It wouldn’t be a Jewish podcast without a little bit of Jewish guilt. So if you enjoyed this episode or any of our episodes, please subscribe, rate, review, tell your friends about it. You could also donate at 18forty.org/donate. It really helps us reach new listeners and continue putting out great content. You could also leave us a voicemail with feedback or questions that we may play in a future episode, and that episode is coming soon. So be sure to leave that voicemail at 917-720-5629. Once again, that number is 917-720-5629. If you’d like to learn more about this topic or some of the other great ones we’ve covered in the past, be sure to check out 18forty.org. That’s the number 18, followed by the word Forty, F O R T Y.org, where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails. Thank you so much for listening, and stay curious, my friends.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

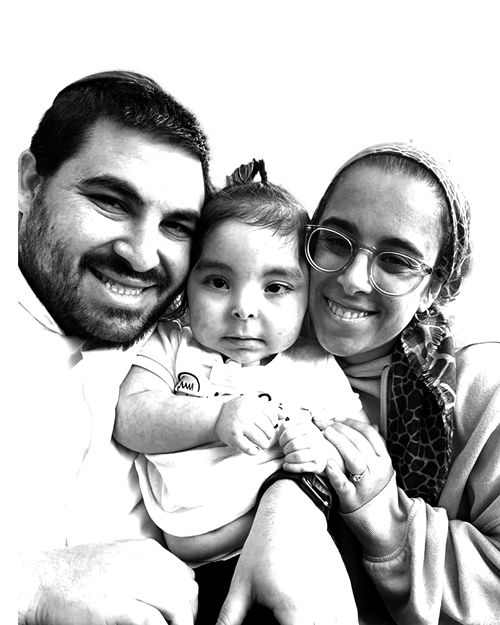

Hadas Hershkovitz: On Loss: A Husband, Father, Soldier

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Hadas Hershkovitz, whose husband, Yossi, was killed while serving on reserve duty in Gaza in 2023—about the Jewish People’s loss of this beloved spouse, father, high-school principal, and soldier.

podcast

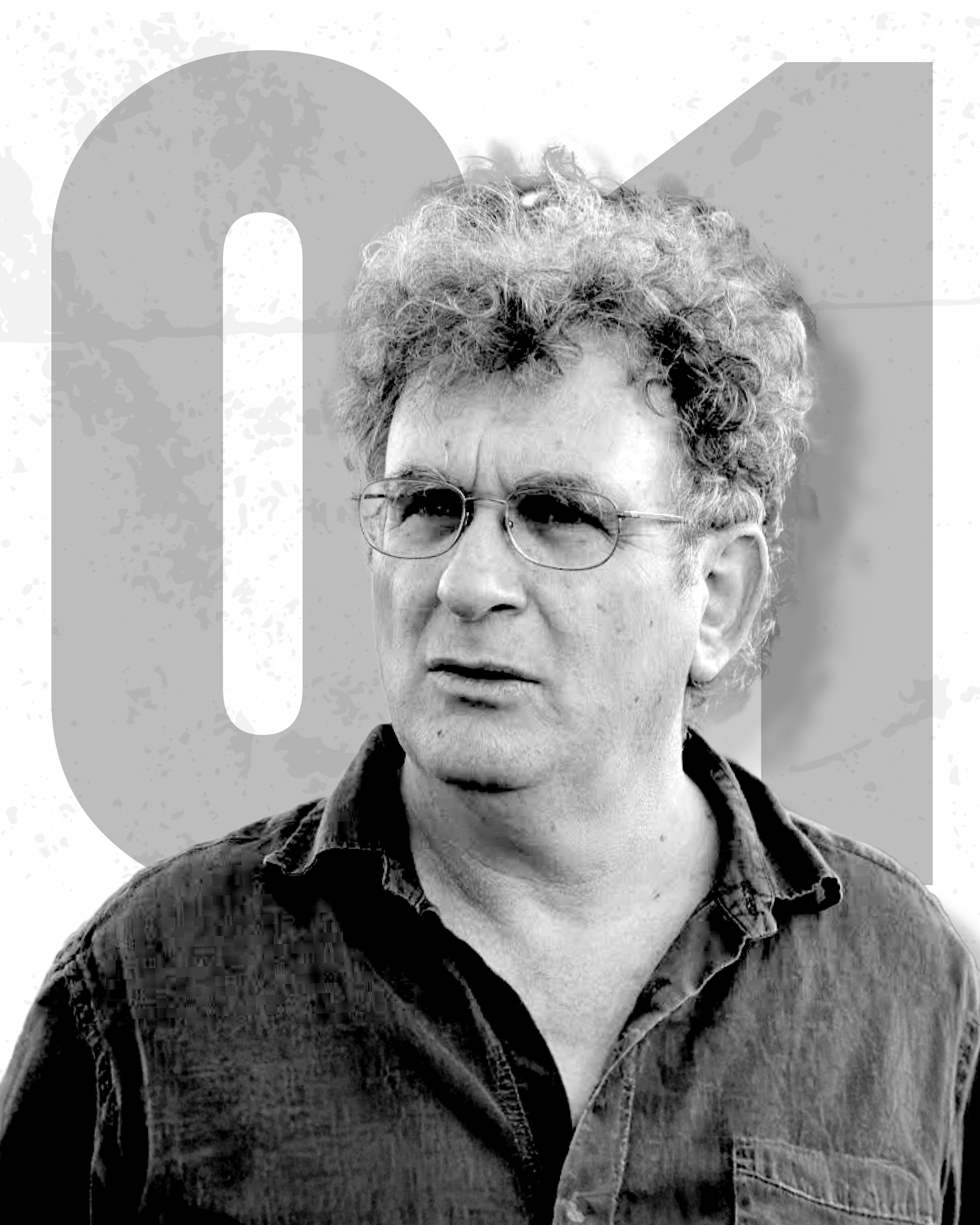

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Elissa Felder & Sonia Hoffman: How the Jewish Burial Society Cares for the Dead

Elissa Felder and Sonia Hoffman serve on a chevra kadisha and teach us about confronting death.

podcast

How Different Jewish Communities Date

On this episode of 18Forty, we explore the world of Jewish dating.

podcast

Red Flags: A Conversation with Shalom Task Force Featuring Esther Williams and Shana Frydman

We have a deeply moving conversation on the topic of red flags in relationships.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Shlomo Brody & Beth Popp: Demystifying Death and the End of Life

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Shlomo Brody and Dr. Beth Popp.

podcast

‘Everything About Her Was Worth It’: The Life of Yakira Leeba Schwartz A”H

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Yisroel Besser, who authored many rabbinic biographies and brought David Bashevkin to Mishpacha magazine, about sharing Jewish stories.

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Benny Morris: ‘We should have taken Rafah at the start’

Leading Israeli historian Benny Morris answers 18 questions on Israel, including Gaza, Palestinian-Israeli peace prospects, morality, and so much more.

podcast

Rabbi Meir Triebitz: How Should We Approach the Science of the Torah?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rabbi Meir Triebitz – Rosh Yeshiva, PhD, and expert on matters of science and the Torah – to discuss what kind of science we can learn from the Torah.

podcast

Anshel Pfeffer: ‘The idea that you’ll obliterate Hamas is as realistic as wanting to obliterate Chabad’

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu did not surprise Anshel Pfeffer over the last 17 months of war—and that’s the most disappointing part.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Larry and Tzipora Rothwachs: Here Without You — A Child’s Eating Disorder

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Larry Rothwachs and his daughter Tzipora about the relationship of a father and daughter through distance while battling an eating disorder.

podcast

Anita Shapira: ‘You cannot wipe out Hamas’

Leading Israel historian Anita Shapira answers 18 questions on Israel, including destroying Hamas, the crisis up North, and Israel’s future.

podcast

Talia Khan: A Jewish Israel Activist and Her Muslim Father

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Talia Khan—a Jewish MIT graduate student and Israel activist—and her father, an Afghan Muslim immigrant, about their close father-daughter relationship despite their ideological disagreements.

podcast

Frieda Vizel: How the World Misunderstands Hasidic Jewry

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Frieda Vizel—a formerly Satmar Jew who makes educational content about Hasidic life—about her work presenting Hasidic Williamsburg to the outside world, and vice-versa.

podcast

Gadi Taub: ‘We should annex the north third of the Gaza Strip’

Gadi answers 18 questions on Israel, including judicial reform, Gaza’s future, and the Palestinian Authority.

podcast

Lizzy Savetsky: Becoming a Jewish Influencer and Israel Advocate

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Lizzy Savetsky, who went from a career in singing and fashion to being a Jewish activist and influencer, about her work advocating for Israel online.

podcast

Mikhael Manekin: ‘This is a land of two peoples, and I don’t view that as a problem’

Wishing Arabs would disappear from Israel, Mikhael Manekin says, is a dangerous fantasy.

podcast