This essay is the last in the author’s four-part series for 18Forty’s explorations of the origins of Judaism. The third can be found here. The entire series can be found compiled here.

Modernity brought changes to the Jewish community both big and small—and the siddur was not immune to the currents of Enlightenment sweeping through Europe. The relocation of Jews to Israel and the United States in the wake of the Holocaust also challenged the traditional siddur in various ways. This final article in my siddur series will explore the impact of modernity on the siddur, including varied attempts to modify it. This includes both the overt changes made in Reform congregations and other denominations, as well as more subtle changes affecting even Orthodox communities.

Correcting the Siddur

Once the siddur was printed and widely disseminated in the 1600s, scholars were more readily able to scrutinize its text. The Enlightenment further brought to bear an interest in scientific accuracy with grammarians and editors seeking to establish the most accurate version of the siddur. Errors surely crept into written manuscripts, they argued, and printers often made errors of their own.

Rabbi Eliyahu of Vilna (1720-1797), known as the Gra or Vilna Gaon, was among many who corrected the siddur text. But I’ll focus on a somewhat lesser-known figure: Rabbi Zalman Hanau (1687-1746), whose emendations to the siddur in his work Sha’arei Tefillah had a lasting impact on Nusach Ashkenaz. Hanau altered words based on principles of biblical grammar, even when such changes ignored the established nusach. For example, as attested to in the Berachot 11b, the blessing recited over Torah study includes the following words:

וְהַעֲרֵב נָא, ה׳ אֱלֹהֵֽינוּ, אֶת־דִּבְרֵי תוֹרָתְךָ בְּפִינוּ וּבְפִיפִיּוֹת עַמְּךָ בֵּית יִשְׂרָאֵל

And sweeten for us, Hashem, our God, the words of Torah in our mouths and in the mouths of [u-vi-fifios] Your nation, the House of Israel.

Hanau was troubled by the unusual word fifios for “mouths” and also opposed other versions of the blessing that used the word fios. Hanau therefore corrected the word to the simple fi which, in his estimation of biblical grammar, was a perfectly acceptable plural form of the word.

Hanau’s method of correcting the siddur was echoed by other grammarians such as Rabbi Yitzchak Satanow (1732-1804), a colorful and controversial Enlightenment-influenced figure. Satanow wrote:

לשון תורה לחוד ולשון חכמים לחוד וחייב אדם להתפלל בלשון מקרא

The language of the Torah is one thing, and the language of the Sages is something else. One is obligated to pray in the language of Scripture.

But this approach did not go unchallenged. Rabbi Yaakov Emden (1697-1776), in his typically blistering style, attacked Hanau’s corrections in his work Luach Eresh, arguing that “in our siddurim and in the formulation of our berachot, we are not accustomed to the Hebrew of Scripture.” Emden was particularly loath to change the traditions of Nusach Ashkenaz.

In the end, though, despite Emden’s criticism, it is Hanau’s version of the Torah blessing with the word fi that has become the accepted version in Nusach Ashkenaz. (Sephardi siddurim retain fifios.)

Although Rabbi Emden carries more weight in our halachic tradition than Rabbi Hanau, Hanau’s emendation was accepted by the two German titans of nusach in the 19th century: Wolf Heidenheim (1757-1832) and Seligman Baer (1825-1897). Heidenheim composed Sefat Emet (not the chassidic work), an authoritative Ashkenazi siddur largely based on manuscripts. Baer, Heidenheim’s successor, composed Siddur Avodat Yisrael in 1868, a carefully researched and impressively annotated work from which all contemporary Ashkenazi siddurim descend. Baer’s preference for fi over fifios sealed the deal.

Changing the Siddur: Non-Orthodox Approaches

Despite their emendations, Heidenheim and Baer were largely faithful custodians of the traditional nusach ha-tefillah. And in many parts of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East, even as the fabric of traditional life began to fray, Jews continued to pray as they had for centuries. Sephardic communities generally did not modernize their siddurim and stayed faithful to the traditional prayers.

But the German Reform movement sought to change the siddur wholesale.

In Reform siddurim, piyyutim were limited and kabbalistic prayers eliminated. The prayerbook of the Hamburg Temple, which opened in 1818, excised mention of the return to Zion and restoration of the sacrifices. Church decorum was imported to the synagogue: The organ was played, a choir sang hymns, and the rabbi and cantor wore clerical garb. Orthodox rabbis were of course quick to denounce these changes.

In America—a hotbed of religious experimentation—liturgical change took full flight. In the Union Prayer Book, a Reform siddur published by the Central Conference of American Rabbis in 1895, Shema is truncated, Shemoneh Esrei contains only a couple berachot, there is only one Kaddish, English translations are offered in place of the Hebrew, and new English readings are added. The siddur even opens from left to right like an English book. (In recent years, however, the Reform movement has returned to more traditional modes of prayer. Current Reform siddurim include more Hebrew, contain some piyyutim, and mention mitzvot such as shofar, lulav, kiddush, and reading the megillah—practices that were abandoned by earlier Reform adherents.)

Similarly, the 1945 Sabbath Prayer Book of Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan (1881-1983), who headed a wing of the Conservative movement that eventually became Reconstructionist Judaism, proposed radical changes to the traditional liturgy. Kaplan, who was uncomfortable with the concept of Jewish chosenness, omitted the phrase asher bachar banu mi-kol ha-amim—that God chose us from all the other nations—from the siddur. He also excised most of the second paragraph of Shema (probably because it speaks of reward and punishment in a visceral and non-rational manner). Kaplan did not believe in the divinity of the Torah, so he eliminated almost the entire phrase we recite when the Torah is raised for the congregation to see when it is read (hagbah) aside from its opening words of ve-zot ha-Torah, because it speaks of Moshe receiving the Torah from God and giving it to the Jewish people. And in a quixotic turn, Kaplan, who was enamored with the promise of America, added special services for American holidays such as the Fourth of July, which included reciting the Declaration of Independence and singing songs like “America the Beautiful” and “My Country ‘Tis of Thee.”

The mainstream Conservative Movement was more circumspect when it came to change. Its first Sabbath and Festival Prayer Book issued in 1946 proposed only minor changes, such as speaking about sacrifices in the past tense in Shabbat Musaf without hoping for their restoration. As the editors wrote in the introduction—possibly in response to Kaplan—larger changes were rejected:

There will naturally be instances, however, where re-interpretation is impossible and the traditional formulation cannot be made to serve our modern outlook. Such pre-eminently are the passages dealing concretely with animal sacrifices. … The deletion of the Musaf service as a whole, however, would mean destroying the entire structure of the traditional liturgy…

Today, Conservative siddurim sport additional modifications. Many Conservative congregations, for example, add the matriarchs to the first blessing of Shemoneh Esrei alongside the patriarchs. Nonetheless, Conservative siddurim remain quite traditional overall.

Orthodoxy and Change

Orthodox Jews are reticent to modify the language of tefilla. Yet, certain prayers have begun to be omitted from the siddur even in the most fervent congregations. Many shuls have ceased saying yotzrot—the piyyutim (liturgical poems) for the Arba Parshiyot (the four special Shabbatot leading up to the month of Nisan and Pesach). Even fewer congregations in America nowadays recite the piyyutim that were traditionally part of Nusach Ashkenaz in Maariv, Shacharit, and Musaf of Yom Tov. And although piyyutim are still said on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, it seems like shuls say fewer each year. New editions of the machzor, such as the one by Koren Publishers, relegate more piyyutim to the back of the book than prior editions—such as the one published by ArtScroll—acknowledging the trend toward omission. These rarely discussed changes are likely driven by modern synagogue-goers who have little patience for dense Hebrew poetry.

Particularly in the United States, publishers and editors have labored to make the siddur easier to navigate and understand. Many siddurim historically lacked directions and translated the prayers into archaic English, if at all.In his masterful 1959 defense of traditional Judaism in This is My God, the novelist Herman Wouk complained that in shul, the worshipper

is handed a prayer book that strikes him as a jumble, with English translations that for long stretches make little sense. … Now and then everybody stands, he cannot say why, and there is a mass chant, he cannot say what; or if he dimly recalls it from childhood, he cannot find it in the prayer book. … The [Torah] reading in a strange Oriental mode seems endless, and he observes that it seems endless to some other worshippers too, who slump in an unfocused torpor, or chat, or even sleep. … The skeptic leaves—early, if he can—well satisfied that his views are sound, that his religious fancy was a temporary touch of melancholia, and that if the Jewish God exists, there is no reaching him through the synagogue.

Dr. Philip Birnbaum, the American translator I quoted in the first article in this series, similarly lamented the “gross carelessness” of siddurim that included pages “broken up by several type sizes which have a confusing effect on the eyes of the reader” and translations that were “a vast jungle of words from which a clear idea only rarely emerges.” His 1949 siddur, which corrected these deficiencies, sold hundreds of thousands of copies around the world.

The 1984 ArtScroll siddur, which has captured the English-speaking market, capitalized on these improvements. It presents the prayers in a crisp typeface and user-friendly format. Its translation matches the Hebrew word-for-word, making it easier both for the uninitiated to follow along and the experienced davener to quickly check the translation of unfamiliar words. The ArtScroll siddur also includes a commentary explaining the meaning of unusual phrases and a comprehensive halachic guide that includes instructions for what to do if one makes a mistake.

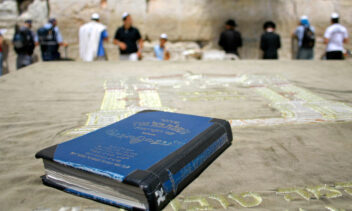

The Nehalel Siddur, prepared by Michael Haruni in 2013, is one of the most interesting Hebrew-English siddurim, although not widely used. Haruni includes full-color photographs of mountains, fields, people, and other subjects. According to Haruni, “The juxtaposing of photographs that portray the meanings of texts can help us deal with” the problem of “focusing on what our prayer is all about.” Some may find the images distracting, but the approach is certainly inventive.

Yet I consider the Nehalel Siddur even more thought-provoking because of its translation of one particular passage. As we’ve discussed, in Shemoneh Esrei, we call for the restoration of God’s presence to Jerusalem. The words ha-machazir shechinato le-tzion are usually understood as something that will occur in the future—we pray for a Messianic era in which God will return to Zion. The Nehalel Siddur, however, translates the phrase as saying that God “is reinstating His presence in Tziyon”—in the present tense. This subtle, but remarkable shift—which still fits with the Hebrew—reimagines the prayer for our times, when the State of Israel is vibrant and flourishing. Could it be that Israel’s rebirth is indeed the beginnings of the Messianic redemption for which we have prayed for centuries?

Indeed, when the State of Israel came into being in 1948, rabbis needed to confront head-on how to commemorate what happened. Should Hallel, which is recited at other moments of joy and salvation, be recited? If so, should the beracha be included or omitted? Perhaps a new Al Ha-Nissim, like the ones commemorating the miracles on Chanukah and Purim, would be more appropriate? Should the Torah be read? Can a Haftarah be added? When I look at Koren’s prayer book for Yom Ha-Atzmaut and Yom Yerushalayim, I am struck by how raw and unsettled these debates remain, even nearly 75 years later. The siddur presents the service approved by the Chief Rabbinate of Israel but also includes other options with texts expressing different ideas. And as is well-known, the liturgy for Yom Ha-Atzmaut divides Orthodoxy—charedi and yeshiva communities do not commemorate the day in davening.

The Siddur as the Book of Faith and Tradition

Controversies over the siddur have sometimes become quite heated—literally. In the mid-19th century, an Orthodox Jew in Cincinnati named Schachne Isaacs burned Minhag America, a Reform prayer book written by Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise. Mordecai Kaplan’s siddur also sent shockwaves through the American Orthodox establishment, particularly because Kaplan had begun his career as a prominent Modern Orthodox intellectual and was the first rabbi of the Jewish Center on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. In June 1945, the Agudas Harabbonim, a rabbinic group, excommunicated Kaplan and publicly burned his siddur. The news made it into the New York Times. It is somewhat shocking that Jewish books were publicly burned in America, and sad that they were burned by other Jews.

Why does changing the siddur evoke such extreme reactions? For one, there are serious halachic and hashkafic (theological) concerns about modifying the prayers. The siddur is the book of faith, says Rabbi Jonathan Sacks. “We do not analyze our faith,” he writes, “we pray it.” For better or worse, the siddur becomes one arena where we fight our theological battles. The question of Hallel on Yom Ha-Atzmaut is a struggle over the religious meaning of the modern State of Israel. The issue of the return of Temple sacrifice speaks to nothing less than how we envision the Messianic era and whether we even believe that there is one yet to come. These are not small questions.

Moreover, we speak to God through the siddur. It is healthy to be possessed by a certain trepidation when we approach our Creator. Yihiyu le-ratzon imrei fi—“May the utterance of my lips meet with favor,” we mutter at the close of Shemoneh Esrei. We want to make sure we are saying the right words. And that’s another reason why the modification of the siddur becomes such a weighty matter.

The Nobel-Prize-winning Israeli storyteller S.Y. Agnon relates a tale about the 19th century German Reform Rabbi Samuel Holdheim. (Attentive readers might remember him from my 18Forty series on the Oral Torah.) In the story, Holdheim institutes major changes to the Yom Kippur liturgy in his synagogue, shortening it considerably. Yom Kippur afternoon—during the long break—his congregants see him in a café across town. Their rabbi, they imagine, is practicing something akin to what he preached—after leaving the truncated service, he is eating! But when they look closer, they see Holdheim hunched over a siddur, reciting all the prayers they had skipped earlier.

I don’t quite know what to make of this story—and one wonders if it is apocryphal—but it says something powerful about the pull of tradition and how the siddur is not easily abandoned.

Still, prayer is not easy, and deep engagement with the siddur does not arise on demand. As Herman Wouk writes:

Perhaps for saints and for truly holy men fully conscious prayer is really an everyday thing. They live, in that case, in clarity that plain people do not know. For the ordinary worshipper, the rewards of a lifetime of faithful praying come at unpredictable times, scattered through the years, when all at once the liturgy glows as with fire. Such an hour may come after a death, or after a birth; it may strike after miraculous deliverance, or on the brink of evident doom; it may flood the soul at no marked time, for no marked reason. It comes, and he knows why he has prayed all his life.

For Wouk, daily prayer is a discipline that pays dividends in moments of crisis and ecstasy.

Yet, for me, the story of the siddur’s development can ground even the humdrum times when davening seems more of an obligation than an inspiration. The siddur has changed over time, bent this way and that in the arc of Jewish history. But it has also remained remarkably constant, lovingly preserved by those who hung onto its every word. When I pray, I feel connected to Knesset Yisrael—literally the synagogue of Israel—throughout the generations.

The siddur consists of the words uttered by our Sages of old. Those words became the words of Jews who perished al kiddush hashem and the words of Jews who passed through the fire and emerged. They are the words sung following the birth of a child and the words whispered in the moments before death. Yet they are also the words said day in and day out by ordinary men and women of faith. They are the words of our mothers and fathers. When we open the siddur, they become ours.

I want to thank the members of the Facebook group “Passages of Rite: Exploring the History of Nusach HaTefilah” for answering my many questions as I was writing this series. In particular, I want to thank Nate Light and Shlomo Katz for reviewing drafts of each article.

Yosef Lindell is a practicing lawyer and the Managing Editor of the Lehrhaus. He has a JD from NYU Law and an MA in Jewish history from Yeshiva University. Yosef’s writing spans several genres, from science fiction to scholarship, and he’s published more than 30 articles on Jewish history and thought. He lives in Silver Spring, MD, with his wife and two sons. His website is yoseflindell.wordpress.com.