Shulem Deen: Faith, Without Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David discusses with special guest and former member of the Ultra-Orthodox community, Shulem Deen, the struggle and importance of balancing one’s individual needs with those of the community.

Summary

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David discusses with special guest and former member of the Ultra-Orthodox community, Shulem Deen, the struggle and importance of balancing one’s individual needs with those of the community.

Though many of us are aware of the extreme disconnect that exists between the Ultra-Orthodox Jewish community and the secular world, the result of this unfortunate dynamic offers powerful insight. In particular, the intense and likely under-discussed experience of ex-Ultra-Orthodox community members (a group referred to by many as ‘Off The Derech’ or OTD) raises important questions about the reality of this intercommunity conflict and life as a modern Jew.

- In what ways do the religious and secular worlds misunderstand each other?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the Ultra-Orthodox and secular worlds in facilitating a positive life for their members?

- How can we as individuals combat the inescapable myopia of living within a social bubble?

Tune in to join David and Shulem in seeking answers to these important questions.

Transcript

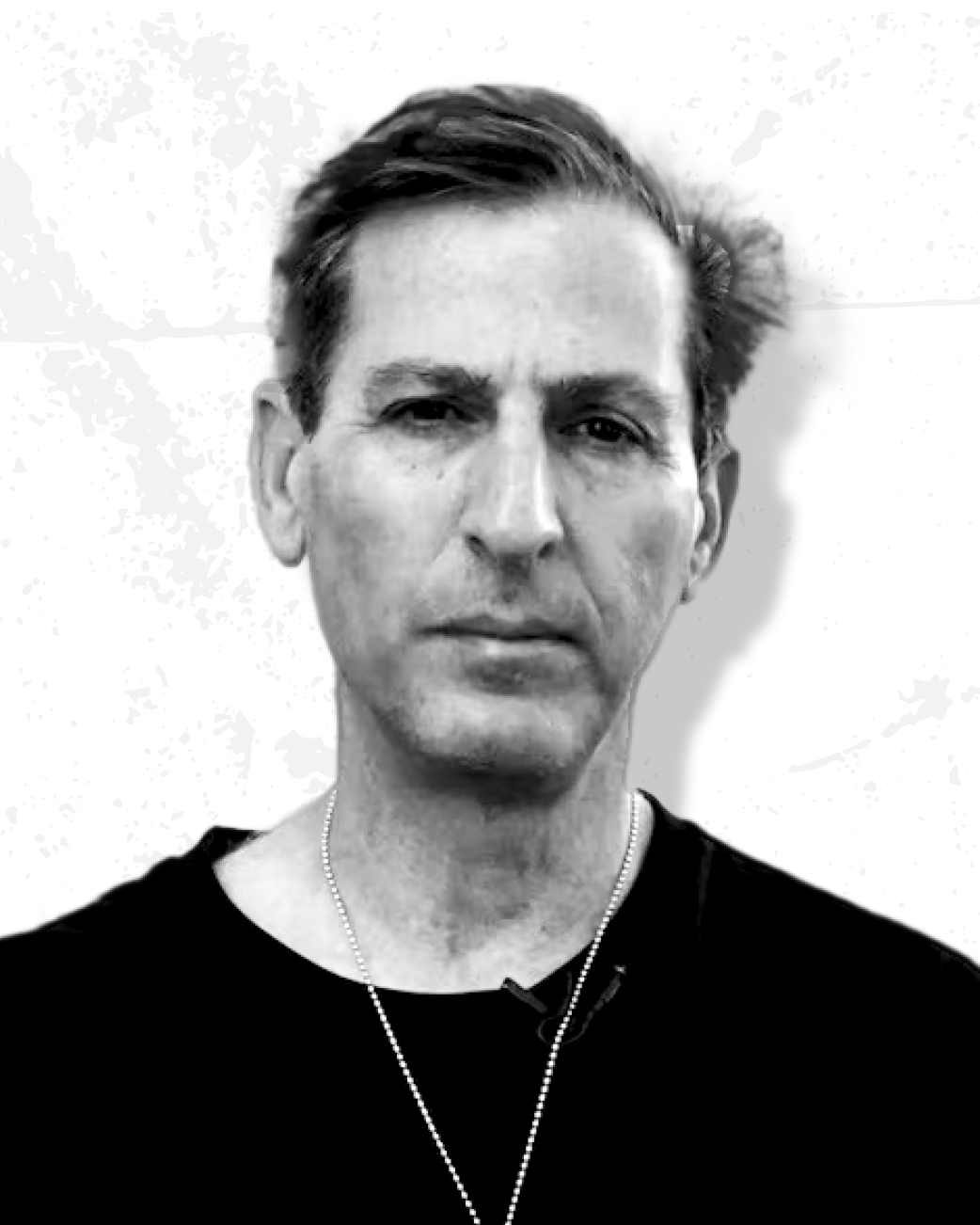

David Bashevkin:

Welcome to the 18Forty podcast, where we discuss issues, personalities, and ideas about religion and traditional world confrontation with modernity, and how on Earth are we supposed to construct meaning in the contemporary world right now. It is such a joy to be sitting here today with someone who I am pleased to call a dear friend: Shulem Deen. He’s the author of a memoir called All Who Go Do Not Return. I’m so proud I didn’t butcher the title. It’s a famously butchered title. But Shulem, thank you so much for being here.

Shulem Deen:

It’s an absolute pleasure to have you here in my home.

David Bashevkin:

It’s really a joy. So for those who haven’t read your memoir, which I want to talk about some of the larger themes that emerge from it, but those who haven’t read it, can you explain a little bit about what was the world and the community you grew up in and where are you now?

Shulem Deen:

Oh man. It sounds like an easy question, right? The thing about talking about the same thing for three, four, five, six years is that you lose fluency in the thing that you’re saying because you forget to actually think about it. Your responses become rote, so you lose the freshness of the response. To describe the world I came from, I mean…

David Bashevkin:

What community were you born and raised in?

Shulem Deen:

I grew up in Borough Park, sort of general Hasidic community, in a world that was, I would say, most closely aligned with Satmar or Satmar affiliated groups. Satmar ideology but somewhat more liberal, somewhat more Borough Park, for those that might know what that signifies, somewhat more balabatish. Then I became a Skverer Hasid in my teenage years. I went to Skverer Yeshiva and then later I got married in New Square started a family. My then wife was from New Square, born and raised. I had five children, they were all born and raised in New Square. They’re still in… well, most of them are still in New Square. One of them is married and moved to Monsey, moved to the big open diverse world of Monsey.

David Bashevkin:

You clearly are no longer living in Skver. At what age did you decide to leave that community?

Shulem Deen:

It was obviously a process of many years thinking about my beliefs, thinking about the community I was in, thinking about the broader community that that community is situated within, that is the broader Hasidic world, the broader ultra-orthodox world, and it was a process of questioning, of reading, of thinking, until I realized over time that I did not really believe in the principles of that community, in the foundational principles not only of the Skver community, but also of Orthodox Judaism. So when did I leave? That’s an interesting question. Did I leave when, in my mind, I decided I was no longer frum but was still married and had five children and was still wearing a shtreimel and a bekishe and going to shul every shabbos, but turning on lights in my home, and occasionally when my wife was gone I would watch a movie or something like that… Was that when I left? I think that could be one point. That was sometime in my late 20s, or I would say sometime in my late 20s was when I came to a very definite conclusion that I am not a believer, whatever that can mean. Being a believer has many shades, but broadly…

David Bashevkin:

That was an evolution of sorts. You don’t look at it necessarily as a before and after of a certain date and a certain incident.

Shulem Deen:

Right. There was a before and after that I don’t define as so much my leaving as much as my being pushed out. That was more I took steps in response to steps other people had taken. For instance, I was living in New Square with my family and I was summoned by the New Square beis din, the rabbinical court. They had heard rumors that I was a nonbeliever, and so they said, “There’s no place for you in this community,” and they ordered me to leave: to sell my house, to pack up my things, and to move away. In a place like New Square, for those who know, they actually have the power to do that in various ways. Obviously they don’t have the legal power, at least not in the secular sense of –

David Bashevkin:

But it’s controlled and insular in a certain way that’ll…

Shulem Deen:

Right. They have the social power that can make you leave. So they insisted that I leave the community, so that was one very definite break, but it wasn’t a full break because I moved with my wife and my children to Monsey where we continued to live a frum chassidish life, actually, for another couple years, we tried that. In the end that didn’t work, so my wife and I came to the realization that it just didn’t work for us any more. Our marriage wasn’t working for us, and my living within a world that I didn’t believe in and felt so alienated from, felt increasingly alienated from… I just couldn’t stay. That led to the breakdown of our marriage, and that’s a very definite point at which I decided, “Okay, now I no longer need to be living a pretend religious life. I can just be living as I am, except for when my children come to me,” then I would back into my old – but that was just for whenever they would visit. They were only visiting for the first two years and then my relationship with them was completely cut off, so even that was completely gone.

Let me first say regarding my book being situated within a genre of OTD writings, it’s clearly the case that it can be classified within that genre, but I wasn’t writing from within that genre. I was writing because I was interested in writing. I was interested in literature. So I wrote a book about my – and mined my own experiences for a literary project. I get that it’s my insistence on this is, as much I’m going to hock about, “No, my book is not an OTD book, it’s literature. It was a literary undertaking,” the world is not going to see it that way.

David Bashevkin:

I’ve heard you express something really eloquent about that. We one time had an opportunity to be in a high school in California together, and I remember one of the students asked you, “Why isn’t your book angrier given everything that you had went through?” Given everything, why isn’t it more emotional and more emphatic and more tearing down the place that you came from? Do you remember what the answer was?

Shulem Deen:

I got that question a lot. Do I remember what I said then? I don’t remember what I said then.

David Bashevkin:

I think you were quoting somebody who says, “You have to write from your…”

Shulem Deen:

Write from your scars, not from your wounds.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. Write from your scars and not from your wounds.

Shulem Deen:

I thought I was quoting a friend but he says he never said that, so either I made it up or I took it from someone else.

David Bashevkin:

But there’s a healing, there’s space in the book for the reader where you don’t feel like you’re being shouted at. It doesn’t feel like you were processing, or it was a cathartic book. There was distance between the literary product and your lived experience, which is why I kind of appreciate that you don’t want it placed in that genre and just stamped on that shelf of all the connotations of, “Oh, another OTD memoir.”

Shulem Deen:

Right. Certainly as a literary project, what I wanted to do was I wanted to tell a compelling story and I wanted to tell it well, and as a writer and as an artist, but as a writer in particular, I feel like I need to leave space for the reader to experience their own emotions as they’re taking this in. For me to impose my emotions in a heavy-handed way would not allow the reader to experience it in that kind of real, visceral, immediate way that you want a reader to experience a story. The question about why I was not angry, in part the answer to that is because I was once that. I didn’t leave because of all the problems of the ultra-orthodox world. There were other things going on that made me move away from that world. Once I had a certain distance I was able to see many of the problems that many of us see in that world.

But that wasn’t why I left, so when I criticize that community, I am criticizing not only that community, but also my former self who was part of it and didn’t see these as problems. That gives me a degree of forced empathy, not only because I understand the people who are there and what they’re trying to do, not only am I sympathetic to what they’re trying to do, I was once them. I was once trying to do the same thing. As the years have passed, I’ve gone further and further away from the person that I was as a religious person, so my empathy for what the religious community is trying to do and how they’re dealing with various issues, my empathy for them has probably lessened, because I see myself so much more alienated from that world now. I see myself situated, not only am I out of the frum world, in many ways I no longer see myself as part of the ex-orthodox world. I’m living my life, I’m busy with a lot of things. That makes me be more angry, when I look at some of the things that are happening within the frum world, and it’s an anger that is new to me, because I forget that I once understood what was going on in that world and wasn’t that angry, and now I only see it from the outsider perspective. Maybe not only, but I see it much more from an outsider perspective.

David Bashevkin:

One of the things that I remember you talking about, and it relates to reflecting on the values that make religious communities unique, is I remember you challenging a group of teenagers that spoke about the importance of Jewish values. You asked them –

Shulem Deen:

What are Jewish values?

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, “What are Jewish values?” I’m curious how that’s changed. When you’re in a religious community it’s hard to think about what your values are and not just… You don’t really think about it because it’s what you do every single day, it’s the David Foster Wallace conversation of “What is water?” I don’t know, it’s where I live every morning.

Shulem Deen:

The problem with it also is that the answer to the question “What are Jewish values?” has to go beyond your religious values. In other words, it has to be something universal, otherwise you could say, “My value is following the 613 mitzvot,” but that is not in itself a value. The underlying value is following the will of God. So you can say, religious people have the value of following the will of God, but the problem with that is that we have a broader Jewish world that often speaks of, quote, Jewish values, and those Jewish values do not necessarily mean following the will of God, observing the commandments, being religious in a traditional sense. So what are those Jewish values? Some people think Jewish values are basically being a good liberal progressive, which of course is –

David Bashevkin:

Education, get into the Ivy League –

Shulem Deen:

Right, education, but also caring about issues of social justice and things like that. I mean, it’s nonsense to say that those are Jewish values. Of course they’re Jewish values. They’re Jewish values in the same way that Jews value being nice to other people.

David Bashevkin:

They’re not not Jewish values.

Shulem Deen:

They’re not not Jewish values, right. Education is a Jewish value, sure, but it’s a value for pretty much –

David Bashevkin:

Everybody.

Shulem Deen:

Everybody wants education.

David Bashevkin:

No one’s on the anti-education team.

Shulem Deen:

Right, exactly. But I think there are some specific things that I look to Judaism and Jewish tradition for, and I think those are very specific to the… I think there are some specific things that we can get from what we might call broadly Judaism that are unique to Jewish religious life, but that would have value for others, and those are many of the things that we might encounter in, say, Pirkei Avot, dan l’kaf zchut, giving people the benefit of the doubt. As a culture, as a society, we do not value giving people the benefit of the doubt. We have a culture that is very happy to quickly assume bad faith rather than good faith. Things like lashon hara, not speaking ill of other people, not gossiping. I don’t think our culture has any appreciation for a value like that. Not speaking lashon hara about someone would mean that the New York Times would have to fold. It means that our media institutions would be out of business except for, they could look like some of the Orthodox publications, but I’m not sure how much value there’s going to be in the New York Times looking like Mishpacha. In some sense, I think, the New York Times can learn from Hamodia, for instance, and I know that many of my friends who are ex-orthodox, and who are so bitterly opposed to ultra-orthodox culture, would be mortified to hear me say that the New York Times could learn something from Hamodia, but I truly believe that. I truly believe that there is a way of seeing the world that grants people more… That is more charitable to the world generally. I don’t think that our media institutions would thrive if we were to be more charitable about other people and their intentions.

David Bashevkin:

I’ve always been fascinated about, I was there when that initial conversation took place and how you spoke about Jewish values. I probably would’ve raised my hand and said, “The tikkun olam,” which are all important, I’m not knocking any of that. But it totally reframed the values that you appreciate once you… I think you mention hakarat hatov, this primacy of a very ritualized gratitude, and I think you mentioned teshuva, repentance, which I thought was –

Shulem Deen:

The value of repentance. Another thing I would say is the value of the wisdom of previous generations, the value of elders. Now, in secular society, we celebrate youth to such a degree that once one reaches middle age and beyond, it is not only horrifying to themselves to find themselves at that age, which is bad enough, but the world…

David Bashevkin:

Middle age is getting younger and younger. I’m middle age now.

Shulem Deen:

But the world also sees middle age and above somewhere between scorn and a benevolent pat on the head. 80 year old grandfather dancing, video goes viral because it’s cute, and that’s what old people are for. They’re there for their cuteness rather than for the wisdom of having the experience of living, the wisdom that comes from the experience of having lived a long life. I think our society in general does not value that. I think Judaism does.

David Bashevkin:

You’re involved in an organization known as Footsteps. You’ve been involved. It works primarily with people who are leaving insular Orthodox communities. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about how you help people who are looking to leave. Their lives, their values, don’t align with the values that they grew up with. How do you help them process the values of religion? Because it is a mixed bag, and every community is a mixed bag. How do you help somebody come to the right decision about whether or not an affiliation with a religious community works for them? Some people, [John] Lennon famously said, “Imagine a world without religion, it would be wonderful.” I could reasonably hear somebody who would take a stance like that. But there are people who, their religious community didn’t work for them. How do you help somebody and guide someone, and I’m sure, given your prominence, a lot of people are coming to you and trying to figure out, “Where do I go from here? Is it the abyss of secularism that I’ve been warned about as a little yeshiva boy where they whisk me away?” How do you help somebody –

Shulem Deen:

“Am I going to get stuck in prostitution or become a drug addict?”

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, correct, like in Times Square, yeah. How do you help somebody navigate the process of leaving a religious community that didn’t work for them, and figuring out, “What would life look like without the religious community that I had? Does that mean I should have zero religion? I should have some? Are there other ways that I could build meaning, value?” How do you help somebody arrive at the decision that works for them?

Shulem Deen:

First I want to clarify and state this just for the record: My affiliation with Footsteps, I’ve been very proudly associated with Footsteps for many years, but I don’t work for Footsteps, I’m not an employee of the organization. I am a board member, and I’m a very strong advocate of their work, but I don’t want to conflate my own position with what Footsteps does as an organization, not because they’re necessarily different, but theoretically they could be different. I can speak about myself, right? Footsteps as an organization has its own spokespeople.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, that’s all I’m asking.

Shulem Deen:

I will speak about myself. There are people who come to me and they want to discuss the idea of leaving. I have to say, my first impulse when someone says to me, “I want to leave the religious community,” is to say to them, “Don’t.” My first impulse is to say, “Don’t. Don’t Leave.” And that is because I think the cost of leaving is so high that you really have to know why you’re doing it. Obviously the reasons for leaving the ultra-orthodox world are very many. Some people leave because they just can’t get on board with the ideology, or fell off board. Some people leave because they’ve had horrible traumatizing experiences: sexual abuse, this kind of abuse, that kind of – Some people leave because they feel alienated from the environment. I have a friend who’s a brilliant musician but was a really weak Talmud student. When he was a kid, all they were doing was studying Gemara, studying Talmud, and no one, for even a second, thought that maybe this kid could thrive if he was pointed in the direction of music, of –

David Bashevkin:

That’s so funny. That’s not my impression of the – and you would know more than I do – of the Hasidic community. It doesn’t parallel the single-minded focus on talmud study like – and we’ll return to the question in a second – but the single-minded –

Shulem Deen:

As in the Yeshivish world?

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, like in the Israeli Yeshiva world. One of the things I’ve always admired about the Hasidic world as opposed to the Modern Orthodox world in America, is that you can feel the dignity of human experience and have a blue collar job. You can work stocking shelves in a supermarket, you can drive a truck, you can drive a school bus. Obviously you didn’t have those professional opportunities of medicine and law that you would get in the Modern Orthodox world, but there is a dignity of working in a fish market, and I never felt in the Hasidic community that everybody is being geared towards Gemara.

Shulem Deen:

It’s not that everybody… First of all, I would say all of this is relative, so if you’re comparing the Hasidic world to the hardcore Yeshivish world in this particular aspect, in the Torah learning, in their obsessions with bitul Toyra and things like that, sure, the Hasidic world is more relaxed about that. But the Hasidic world traditionally, now it might be changing, but for decades, for the vast majority of the years that organized Chassidus, if you will, existed in the United States, all they had to teach young people is religion, Judaism, Jewishness, shabbos, kosher. You might say that in the Hasidic world there was somewhat more appreciation from what we in the secular world would call spirituality, although Chassidim would, first of all, they wouldn’t know what the term means.

David Bashevkin:

Music in particular I’m surprised. I went to a concert –

Shulem Deen:

But there is no music for a child, for a talented child musician.

David Bashevkin:

Really? I’m not one to push back hard on you. I feel like –

Shulem Deen:

Well, forget about music. What about art? What about this kid who can… I have a friend who’s a really dear friend, different one from this one. He happens to be a musician too but he was a really… He had really severe learning disabilities. I grew up with him and I remember him getting beaten the crap out of by rebbes because he couldn’t read the Rashi. Now, as an adult, he’s a brilliant musician, but what he’s even more brilliant, he’s a brilliant artist. He’s a brilliant painter. When he was a child no one thought for one second that maybe this kid is not that good at Rashi, but he’s really freaking good at music and art. That really does exist. I don’t think that the Hasidic world is any better than the Yeshivish world when it comes to things like that.

David Bashevkin:

I’ll tell you the incident and we’ll return to the question. I was at a concert and Lipa Schmeltzer was playing.

Shulem Deen:

Who is my ex brother-in-law.

David Bashevkin:

So Lipa was there and he hadn’t played around, he was out of the public eye for a while. The way that the Hasidim cheered when he – It was mostly a chassidishe crowd – The way they cheered when he took the stage… I was sitting next to somebody and they said, “You know, the secular press calls Lipa the Jewish Lady Gaga.” He looked at me and he says, “They have it wrong. He’s not the Jewish Lady Gaga, he’s the Jewish Billy Joel. He’s their piano man. He’s the one sharing the experience of the person who maybe wasn’t excelling in learning and have that…” It was just a very touching insight.

Shulem Deen:

Yeah, there’s something very true about that. But consider also, the person, the Chassid you were speaking to knew about Billy Joel.

David Bashevkin:

Oh, no, it wasn’t a Hasid. That I assure you.

Shulem Deen:

What I want to say about Lipa and those who appreciate him is that, first of all, yes, Lipa is a product of the Hasidic world and is appreciated by many products of the Hasidic world, but within the mainstream of the Hasidic world he is not appreciated to the degree that you might think just from seeing some people at a certain event, because it’s a self-selecting group that’s going to be there. Lipa has been banned officially by rabbis in the frum world, specifically the chassidish world. The people who are going to cheer for Lipa, they’re going to be there for Lipa. They’re going to be there because this is an event in which those who do appreciate Lipa, that’s who’s going to be at this event. You don’t really know if this is a representative sampling of the Hasidic world, and I would argue that it is almost certainly not. If you would just stop an average group of chassidim in Williamsburg or in Monsey or even in Borough Park, they would have a very different attitude. If you would just randomly choose a bunch of Chassidim as opposed to going to a Lipa event and seeing the Chassidim there.

David Bashevkin:

Let’s return back to that question of helping somebody make the decision of that affiliation versus non-affiliation. How to do it, how to…

Shulem Deen:

Okay, so what I was saying originally was, I forget how we…

David Bashevkin:

That your instinct initially…

Shulem Deen:

My first impulse is to say, “Don’t.” Somebody comes to me and says, “I want to leave,” I say, “Don’t, don’t leave.” Yes, there are many reasons why people would choose to leave. The most important thing that I would tell someone who wants to leave is, “Know why not only you’re leaving but also what you’re going to. Know what you have outside of the Hasidic world that you don’t have within it. Have a clear understanding of that, or at least something of an understanding.”

I had a woman who I met up with, and she said to me that she was thinking about leaving, and wanted to know whether it’s a good idea or not. So we had a conversation, and she told me that she feels like she’s a misfit in the world that she is. She had good reasons to leave, she had other reasons aside from the fact that she was a misfit, but the fact that she was a misfit, I told her at that time, “If you’re a misfit in the Hasidic world, you might be very well be a misfit wherever you go, because you might just be a misfit in society. You might just be a person who does not fit the box. So you have to really know whether the place you’re going to is a better place than where you’re coming from.”

Some people are just like, “I don’t care where I’m going to end up, I just need to get out of here. I just need to get away from Williamsburg, away from Kiryas Joel, away from New Square,” and I wouldn’t necessarily say that that’s a bad thing, but I wouldn’t encourage someone to do that. If someone comes to me and says, “I want to leave New Square,” my first question is to them, “And go where?” I had a young friend, and I write about this in my book, he was around 19, really unhappy in New Square but very academically gifted. He came to me and said he wants to leave and I said, “And go where,” and he said he wants to enlist in the military. You know, being in the US Armed Forces is a fine thing to do if that’s what you truly want to do, but I wasn’t sure that that’s what he wanted. It seemed to me that he just found the military to be a convenient place where he’ll go and find a social life, and a place to sleep, and meals, and things like that. So I said to him, “I don’t know if you’ve considered this, but you might be really good in college.” He was a kid with so little secular education, he couldn’t even fathom going to school.

David Bashevkin:

The military seemed more realistic –

Shulem Deen:

The military seemed like a very simple idea to him. In the end, he did go to college, and he got accepted into an Ivy League. He got accepted into Cornell University and graduated first with an undergraduate in, I think bioengineering, and then he recently graduated with a masters also in, I forget if it was that or one of the other really hard sciences. Clearly he was capable of something, but he didn’t even know, and he didn’t know this world existed. He said to me, “How could I go to college when I can barely read and write English?” And I said to him, “Well, you’re going to need some help, you’re going to need to get some tutoring, you’re going to have to get your GED, but you can do it.” I knew that he could because he was a really bright kid. That, to me, is a smart thing. I see many people who come out of the Hasidic world and they’re very focused. They really know what they want to do, they have ambitions, they have aspirations, and that is the way to do it. If you have ambitions and aspirations, aside from the fact that you should have ambitions and aspirations, they should also be such that you can’t really do in the frum world.

In other words, say you have an ambition to be a physician, you want to be a doctor or an attorney. I’m not sure that that alone is a reason to not be frum. You might say, “Well, I can’t be Hasidic.” You can. Ruchie Freier is, the Hasidic world likes to hold her up as a great accomplishment, a product of their world that has reached really hard – What is she? A supreme court judge now or something like that. What’s interesting is that they hold her up, now they’re very proud of her, although they never support a young person who says, “I want to grow up and be a judge,” they’re not going to point them in the direction of law school. But still, I think Ruchie Freier is a good example of what you can do if you can think outside the box, if you have aspirations that are different from what everybody else does. You can still have those aspirations and remain frum, so you really want to have a good reason why this world doesn’t work for you. But the most important thing is you need to really know where you’re going. You need to have some sense of what you want to be in the world, what you want to do, but also what you want to be. What’s your dream life, aside from the fact that you no longer have to keep kosher and shabbos and those things. What positive element of living a secular life is going to keep you going? What’s going to inspire you? What’s going to give you the motivation to get up every morning? I think that is the crucial question that somebody needs to answer.

David Bashevkin:

Has your non-religious identity evolved since you’ve left?

Shulem Deen:

Oh, of course. Oh, absolutely. When I left, I didn’t have the social awareness that I have now. I did not know just how deep the wounds of racism in our society go, I had absolutely no idea. I had absolutely no idea how racist I myself was. My thoughts on race, my thoughts on gender, my thoughts on just so many things…

David Bashevkin:

Even after abandoning –

Shulem Deen:

My thoughts on the environment… There are concepts that I never thought I would change my mind on, and I’ve completely changed my thinking on.

David Bashevkin:

Is there a non-religious community that you consider yourself a part of? I’m not asking about your Jewish affiliation. Do you feel like, “I’m able to call myself a liberal progressive, I’m able to call myself a right wing conservative or an environmentalist,” or do you in general look at these group identities with a measure of suspicion because of your earlier experiences?

Shulem Deen:

What’s interesting is that I identify with the group that is skeptical and suspicious of identity.

David Bashevkin:

And that changes.

Shulem Deen:

But that too is identifying with a group. So I have the group of writers and thinkers and public intellectuals who are mounting a certain critique of identity politics, and suddenly I’m realizing, “Wait a second, now I’ve boxed myself into this particular group.” It’s not like I’m a super fan of anybody in particular, but I am a fan of Sam Harris, and I am a fan of Barry Weiss, who is the opinion editor for the New York Times, and who famously commissions opinion pieces by people that get the left really riled up. She and I are friends, and I’m a big fan of hers. I sometimes appreciate thoughtful conservative writers, and friends that I have who think of themselves as really good leftists are mortified that I really like Ross Douthat. I don’t know how his name is pronounced.

David Bashevkin:

He’s new to the New York Times, right?

Shulem Deen:

He’s a devout Catholic, he’s a conservative writer, but a very thoughtful person. He and I might disagree on a whole number of issues, but that’s precisely why I read him,:because I appreciate the difference he brings, and it’s with a thoughtfulness.

David Bashevkin:

I want to ask a question, I wouldn’t be surprised if you’ve gotten it many times. So many Jewish parents, their overriding concern is, “How do I make sure that my children are going to follow in the path of the religious community that I raised them in?” Usually the people who are giving them advice are people who have lived and been raised in the community. I’m wondering what sort of advice you would give to a parent having left that community. What are the themes and missteps that you see parents often making in the way that they raise their children, and eventually they decide to leave? Maybe it’s nothing, but what advice would you give to a parent who says, “How can I create the type of home that people do not want to rebel against?”

Shulem Deen:

Right, so you’re not asking, “What do I say to the parent who wants advice on, how do I make sure my child doesn’t end up like you?” You’re not asking that, you’re asking how do I… because that’s a question that some people might ask: “How do I make sure my child doesn’t go your way?”

David Bashevkin:

I think that’s part of it.

Shulem Deen:

But I think you’re asking a more thoughtful question. You’re asking, “How do I make this world, this society, amenable to those who might not find purpose within it? How do I give them the space to live full, authentic, individualistic lives even within this world?”

David Bashevkin:

Within the framework, yeah.

Shulem Deen:

I think that’s an important question because I am not advocating that people be non-religious. I have no interest in the question of whether a person chooses to be religious or not. I think that if people want to remain religious, they should not be forced out of a religious community because of all the ancillary disfunctions. Granting that this a really important question, the answers I think are the obvious ones. They’re: be open and accepting, be nonjudgmental of your – You have to do the really hard things that you really might not be able to do. If your child is gay, what’s a frum parent to do? Really, what’s a frum parent to do if their child is gay if they want their child to remain in the orthodox community? The thing to do… That’s a real tough one, because even… Take a frum person who is very serious about their frumkite, their Judaism, their religiosity, but they get that not everyone is like this, but they want their child to still remain attached to traditional Judaism, but the child is gay. From a modern secular perspective, where I sit, it’s not a choice. “You’re born with it,” to quote Lady Gaga.

David Bashevkin:

That’s number two. That’s her second Lady Gaga…

Shulem Deen:

Second Lady Gaga reference. But you’re born with it. The only thing to say to a parent is, not just, “Don’t come down hard on your child for being that,” but, “Accept them. Embrace them. Embrace their gayness.” But is that something that you can reasonably expect from an ultra-orthodox parent?

David Bashevkin:

What are the successful – You must know some people who either tenuously stayed or still have relationships with their parents, even though they’re not living a traditionally orthodox lifestyle. What are the ingredients that those parents are able to kind of break out of their comfort zone and be able to embrace a child?

Shulem Deen:

There are the easy situations, and the easy situations are: just don’t hock your child to always, how they dress, what they’re wearing. Your child comes home with a tattoo, compliment them. Say, “Oh, that’s nice. I wouldn’t get one, but it looks good on you.” That’s a difficult thing for many parents. A tattoo is not something that charedi parents are generally in favor of, but your child chose to go a different route, lives a different life, and the only thing you can do if you want to maintain a positive relationship with your child is to say, “Okay, whatever you choose, I accept that.” Now, if you want your child to feel like they belong and… Going back to your question of: “What environment do you create that is going to allow your child to thrive with authenticity, individuality, within this world, within the ultra-orthodox world?” Sometimes the child is simply not going to fit the mold and you need to accept that, and you need to accept that whatever level of attachment they choose is something that you have to be okay with, and then the child can choose that level of attachment. But the moment you say, “No, you can’t do this…” You can say, “I don’t mind if you don’t wear a yarmulke, but you cannot get a tattoo,” or, “I don’t mind if you get a tattoo, but,” and here’s a big one, “you can’t marry a non-Jewish person,” or, “I don’t mind if you marry a non-Jewish person, but you cannot be openly gay. You can’t marry a person of your own gender.” The moment you say this, then your child no longer feels that they can live in your – not even live in your world. Certainly they can’t live in your world, but they can’t even maintain a healthy attachment to it, because fundamentally you are opposed to something that they are fundamentally not only in favor of but something they need.

David Bashevkin:

What advice would you give to the child? So often you’re navigating a new relationship in a way that you’re going off into this new world and, as you said, you can forget that former self and those former values. How do you council somebody who leaves to maintain a relationship with a parent who is still in that world, or family members who are in that world, in a healthy way? Or when is the point where you have to cut them off?

Shulem Deen:

I think what I have to say on this is the opposite of what we hear often, and I think this is what the frum world would like for OTD people to be saying, and that is: respect the community when you come back. Wear a yarmulke, be respectful, but my advice to people who leave is in fact, respect is not a one-way street. You do not have to always accommodate their requests if they do not accommodate yours. This is not because, get back at them, it’s because, if you want to have a healthy relationship, then it requires both sides to accept that the other side –

David Bashevkin:

Reciprocity.

Shulem Deen:

Has – Well, it’s not so much a reciprocity question of quid-pro-quo, tit-for-tat kind of thing, “Okay, you’re going to do something that’s disrespectful to me, I’ll do something disrespectful to you.” That’s childishness. But you also cannot… I’ll give you an example. One of the things that I’ve made a point of is that when I meet with my family, I will sometimes wear a yarmulke and sometimes not. The reason I do that is because I need them to know that I do not wear a yarmulke generally, and I’m not going to always wear a yarmluke just because I’m around them and I need to respect them. I need them to respect the fact that I don’t wear a yarmulke. Now, I wouldn’t walk into a shul without a yarmulke, but that’s also a bit because I’ll get thrown out, or it’s some practical thing. I think shuls should be accepting of people who walk in without yarmulkes. You can suggest, “If you’re looking for a yarmulke there are some on the table there,” but the moment you say, “You need to do X,” that’s the moment the person leaves.

David Bashevkin:

I’m sure you get asked this a lot. You left the ultra-orthodox community. Did you ever think of becoming a Modern Orthodox Jew? And what in general is your take looking out at the Modern Orthodox community? I feel like so much of your perspective is informed from the ultra-orthodox community. I feel like there’s so many Modern Orthodox Jews that hear your story who are like, “Hey, why not us?” What’s your view in your personal life why, did you ever consider becoming Modern Orthodox? And more generally, how do you look at the health, and what’s your perspective on the Modern Orthodox community at large?

Shulem Deen:

This is a really common question that I get, and there are different ways to approach this question. The first response to this is, the first thing I considered was Modern Orthodoxy. When the ultra-orthodox world no longer worked for me, I looked to the Modern Orthodox world assuming that they have the answers to all the big questions about Bible criticism and how science contradicts with chazal, with the Talmudic sages. The first book I went to in the Modern Orthodox world, it’s the classic, Lonely Man of Faith by Rav Soloveitchik. I thought that Lonely Man of Faith is probably going to give me the answers to the big questions for those who have a problem with faith in the modern world. The reality is: the modern orthodox world does not have the answers to those questions. Lonely Man of Faith is a beautiful work, and it’s a classic for a good reason, but it does not address the actual question. It is a much more artful, much more artistic, poetic take on faith in the modern world that really doesn’t, it doesn’t speak to the elementary question of: “How do you reconcile everything we know to be true with everything that traditional Judaism says that is the opposite of that?” So I thought about Modern Orthodoxy, I’ve read on Modern Orthodoxy quite a bit during those stages. Obviously when Rav Soloveitchik didn’t do it for me I read a number of other authors, but ultimately, I didn’t come away feeling that Modern Orthodoxy is a place that is in any way, that satisfies the existential questions I have in a way that the ultra-orthodox world does not. In other words, they didn’t have the answers to these – They had answers to other questions, but the fundamental, existential questions that I had, once I had moved past the idea of divine revelation, of the existence of God, these fundamental questions, there were the basic questions of: “How do you live? What do you believe in?”

David Bashevkin:

It’s a different framework, behaviorally, that helps you navigate in a different way, and maybe opens up more opportunities, but at its core, for you, it didn’t address those foundational questions.

Shulem Deen:

It goes back to the question of: “What does the ultra-orthodox world do well?” It does meaning well, it gives people’s lives meaning. But when that falls apart, does the Modern Orthodox community have a better answer? The answer to me was: “absolutely not.”

David Bashevkin:

My follow up was: what do you see the Modern Orthodox world could learn from the Hasidic world? Do you think that, I mean now there’s this current trend that I’m sure you smirk at of a neo-Hasidic awakening in the Modern Orthodox community. Do you think that Hasidic culture can be transferred into other communities?

Shulem Deen:

I should say, I only smirk at it inasmuch as someone might argue that this is actually Modern Orthodoxy learning from the Hasidic world. What they’re actually doing is they’re finding those innovative texts that even Chassidim find too innovative, and they’re embracing them. The Modern Orthodox world loves Breslov. They love Chabad. They love Izhbits. They love the Piaseczna. They love Radzin. They love the outliers of the Hasidic world.

David Bashevkin:

Those are all my favorites.

Shulem Deen:

Those are all your favorites? And they love those outliers, and they love… The irony is that they love the Chassidim that the Chassidim reject.

David Bashevkin:

But you did grow up in a home where those were on your shelves.

Shulem Deen:

Sure. My childhood… The bookshelves in the home I grew up in had everything, or at least, I should say my father’s bookshelves. They weren’t my bookshelves, I didn’t have access to them. But the bookshelves in my yeshiva and in my kollel, and in the shul where I davened, especially as a Skverer Chassid, the old Skverer Rebbe famously said, “Don’t ask which books you cannot read. Ask which books you can read.” They used to say, the censor in Skver was a very strict one. What they’re essentially trying to say is, the censor in Skver, the czar’s agent, didn’t let us read Chabad and Breslov and Reb Tzadok HaCohen and Izhbits and all that. But really it’s just that, Hasidic communities as they are today are fundamentally conservative ones, not innovative ones, so they too have – We think of the history of Hasidism as being an innovative movement, and the reality is: it was innovative at the beginning but it’s ossified since then, and there’s very little…

David Bashevkin:

As many revolutions do, yeah… stages…

Shulem Deen:

There’s very little innovation now, at least religious innovation. There are some changing attitudes regarding a whole number of things, but there’s very little religious creativity coming out of that world.

David Bashevkin:

It reminds me of, there’s a fabulous quote that says, “The process of acceptance will pass through the usual four stages. ‘It is worthless nonsense’ is the first. The second is ‘This is interesting, but perverse’ point of view. Then third, ‘This is true, but quite unimportant.’ The last one is, ‘I always said so.’” Sometimes a lot of movements pass through this like… it’s dismissed at first and that’s where a lot of the creativity emerges, then once it gets to a point – and I think the Hasidic community, as it lives in New Square and Satmar is, we now look at it as, “I always said so.” That’s the arbiter of authenticity, but it’s…

Shulem Deen:

Of course, I’ve always said this, too.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. Let me ask you, I have a theory – I don’t think I’ve every asked you this question – let’s talk about your accent. I assume that you grew up in a Hasidic community that didn’t have this wonderfully articulate voice that you have now. I wonder, was that a conscious choice? Can you still access that Hasidic intonation?

Shulem Deen:

First of all, I’m flattered that you say this… I hear from many people that I do have an accent. People hear an accent, they can’t quite place it. So it’s not the Brooklyn Hasidic accent you might be accustomed to, but there is something. I don’t hear it but other people clearly do hear it.

David Bashevkin:

I always hear, when I hear you speak, a conscious… like trying to speak like that broadcast tone. It’s very even… A deliberate decision.

Shulem Deen:

Oh, it sounds conscious? That’s horrible.

David Bashevkin:

No… It’s measured in a way. It feels measured.

Shulem Deen:

Interesting.

David Bashevkin:

I wonder if there was a point where you were consciously trying to sound less Hasidic, and are you able to go back? Is your Yiddish still fluent and able to be…

Shulem Deen:

What’s interesting about the accent is, when I speak to Yiddish speakers, I once noticed that if I… Yiddish speakers do phone numbers in English. When somebody asks me a phone number I’ll revert to the Hasidic phone number accent: “What’s your number?” “354-3373.”

David Bashevkin:

You got it. That’s fabulous.

Shulem Deen:

Because somehow that’s become a form of Yiddish: the accented English use of numbers in phone numbers.

David Bashevkin:

You’ll fall back into that.

Shulem Deen:

I’ll fall back to that slightly. I don’t pay attention.

David Bashevkin:

You never did in terms of your…

Shulem Deen:

I don’t pay attention to my matter of speech, not consciously. I probably do subconsciously.

David Bashevkin:

What is your Jewishness mean to you now?

Shulem Deen:

I got this question a lot over the years, and I find that my answer to this has changed over time, and this is interesting to me. But I think my answer now is: Jewishness to me is the most important aspect of my identity. There is no other thing that is as important to me as my Jewishness. For instance… I’m not religiously, philosophically, ideologically opposed to the idea of intermarriage. If I was to marry a non-Jewish person, I wouldn’t need them to be Jewish, but I would need them to have an appreciation for how deep my Jewishness goes in me. That’s something that I’ve realized over the years, I haven’t consciously chosen, and I cannot consciously discard. It’s simply there. I would have to say it’s a connection to the myth of shared ancestry. I think primarily that’s what it would be: the myth of family. The myth that we as a people are not just a religious community, but also a family. The Torah doesn’t refer to Jews as people of a certain faith, the Torah refers to Jews as the B’nei Yisrael, the children of Israel, or Bet Yaakov, the house of Jacob. The Torah refers to Jews as members of a clan, of a tribe that is biologically connected. Now, I don’t think Modern Jews, contemporary Jews today, have that biological connection, and Judaism doesn’t insist on it either because one can convert to Judaism, but there is still even within that, when someone converts to Judaism they take on the name so-and-so Avraham ben Avraham, because that now ties them in a filial way, because Judaism emphasizes the notion that we are a family. So when someone converts there is a very explicit, very conscious, bringing into the family so to speak: an adoption that makes them, not just join this faith community, but actually being adopted as a family member. To me that’s one thing that I just cannot ever see as unimportant. It’s simply part of me. It’s something that I deeply value. The implications of that may be a bigger question, but that’s for another conversation.

David Bashevkin:

Shulem, thank you so much for joining today, this really meant a great deal. Incredibly illuminating and inspiring. Thank you so much.

Shulem Deen:

Thank you so much for bearing through my un-air conditioned apartment on a hot summer day. This has been a pleasure.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

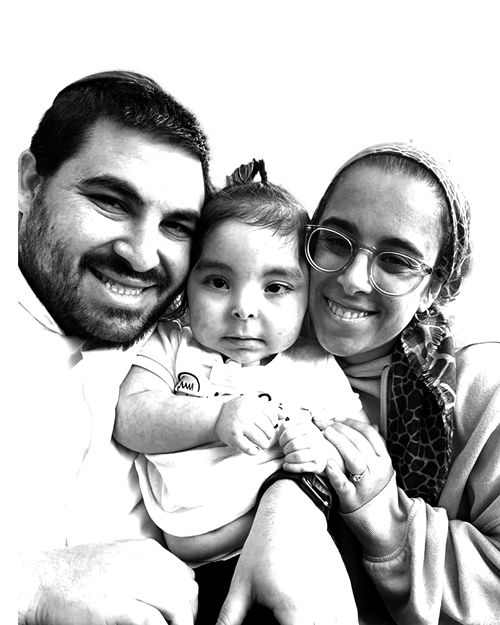

Hadas Hershkovitz: On Loss: A Husband, Father, Soldier

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Hadas Hershkovitz, whose husband, Yossi, was killed while serving on reserve duty in Gaza in 2023—about the Jewish People’s loss of this beloved spouse, father, high-school principal, and soldier.

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Elissa Felder & Sonia Hoffman: How the Jewish Burial Society Cares for the Dead

Elissa Felder and Sonia Hoffman serve on a chevra kadisha and teach us about confronting death.

podcast

How Different Jewish Communities Date

On this episode of 18Forty, we explore the world of Jewish dating.

podcast

Red Flags: A Conversation with Shalom Task Force Featuring Esther Williams and Shana Frydman

We have a deeply moving conversation on the topic of red flags in relationships.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Shlomo Brody & Beth Popp: Demystifying Death and the End of Life

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Shlomo Brody and Dr. Beth Popp.

podcast

‘Everything About Her Was Worth It’: The Life of Yakira Leeba Schwartz A”H

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Yisroel Besser, who authored many rabbinic biographies and brought David Bashevkin to Mishpacha magazine, about sharing Jewish stories.

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

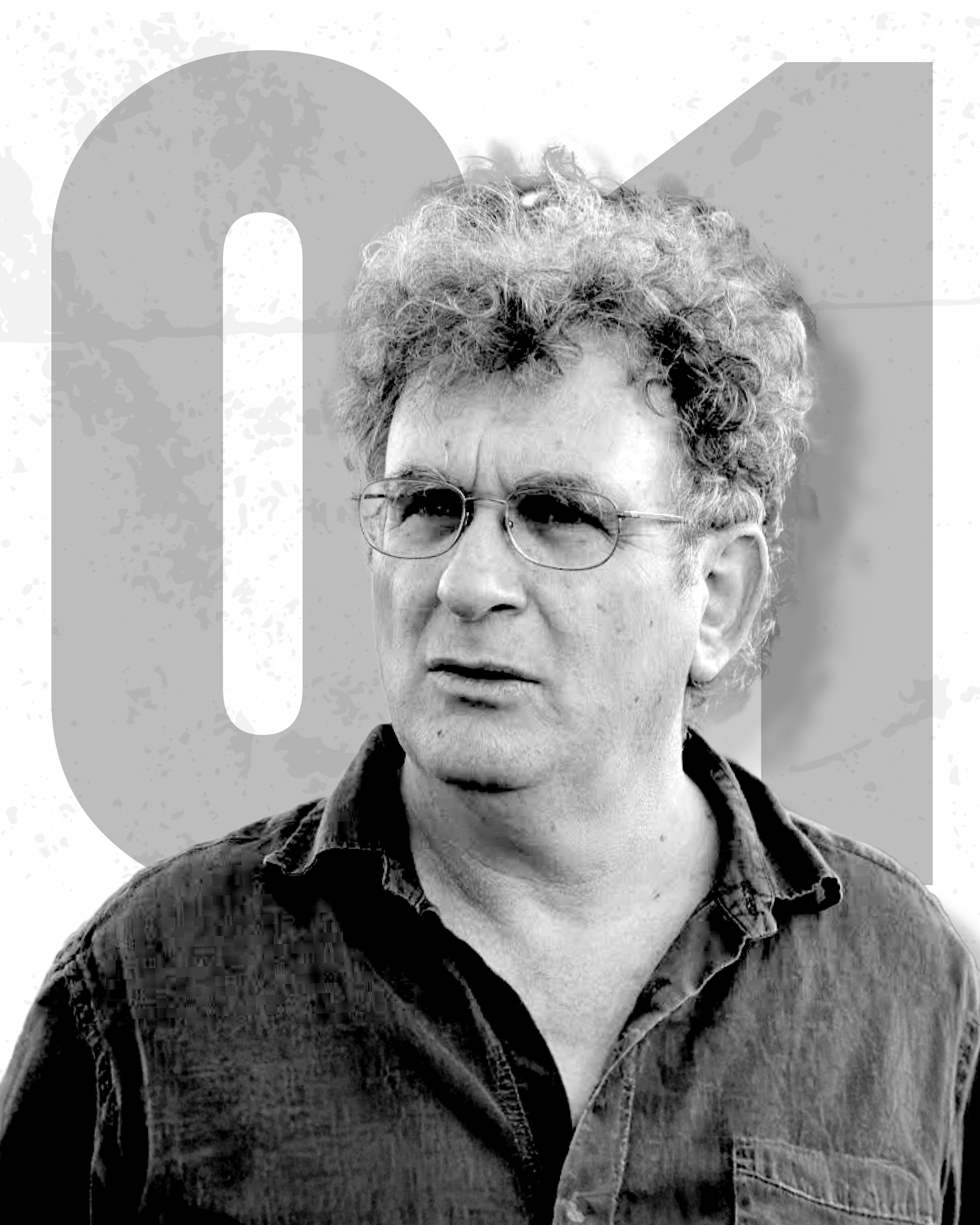

Benny Morris: ‘We should have taken Rafah at the start’

Leading Israeli historian Benny Morris answers 18 questions on Israel, including Gaza, Palestinian-Israeli peace prospects, morality, and so much more.

podcast

Rabbi Meir Triebitz: How Should We Approach the Science of the Torah?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rabbi Meir Triebitz – Rosh Yeshiva, PhD, and expert on matters of science and the Torah – to discuss what kind of science we can learn from the Torah.

podcast

Anshel Pfeffer: ‘The idea that you’ll obliterate Hamas is as realistic as wanting to obliterate Chabad’

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu did not surprise Anshel Pfeffer over the last 17 months of war—and that’s the most disappointing part.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Larry and Tzipora Rothwachs: Here Without You — A Child’s Eating Disorder

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Larry Rothwachs and his daughter Tzipora about the relationship of a father and daughter through distance while battling an eating disorder.

podcast

Anita Shapira: ‘You cannot wipe out Hamas’

Leading Israel historian Anita Shapira answers 18 questions on Israel, including destroying Hamas, the crisis up North, and Israel’s future.

podcast

Talia Khan: A Jewish Israel Activist and Her Muslim Father

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Talia Khan—a Jewish MIT graduate student and Israel activist—and her father, an Afghan Muslim immigrant, about their close father-daughter relationship despite their ideological disagreements.

podcast

Frieda Vizel: How the World Misunderstands Hasidic Jewry

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Frieda Vizel—a formerly Satmar Jew who makes educational content about Hasidic life—about her work presenting Hasidic Williamsburg to the outside world, and vice-versa.

podcast

Gadi Taub: ‘We should annex the north third of the Gaza Strip’

Gadi answers 18 questions on Israel, including judicial reform, Gaza’s future, and the Palestinian Authority.

podcast

Lizzy Savetsky: Becoming a Jewish Influencer and Israel Advocate

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Lizzy Savetsky, who went from a career in singing and fashion to being a Jewish activist and influencer, about her work advocating for Israel online.

podcast

Mikhael Manekin: ‘This is a land of two peoples, and I don’t view that as a problem’

Wishing Arabs would disappear from Israel, Mikhael Manekin says, is a dangerous fantasy.

podcast

Yishai Fleisher: ‘Israel is not meant to be equal for all — it’s a nation-state’

Israel should prioritize its Jewish citizens, Yishai Fleisher says, because that’s what a nation-state does.

Recommended Articles

Essays

This Week in Jewish History: The Nine Days and the Ninth of Av

Tisha B’Av, explains Maimonides, is a reminder that our collective fate rests on our choices.

Essays

I Like to Learn Talmud the Way I Learn Shakespeare

If Shakespeare’s words could move me, why didn’t Abaye’s?

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

Fighting for My Father’s Life Was a Victory in its Own Way

After losing my father to Stage IV pancreatic cancer, I choose to hold onto the memories of his life.

Essays

Books 18Forty Recommends You Read About Loss

They cover maternal grief, surreal mourning, preserving faith, and more.

Essays

Benny Morris Has Thoughts on Israel, the War, and Our Future

We interviewed this leading Israeli historian on the critical questions on Israel today—and he had what to say.

Essays

Why Reading Is Not Enough for Judaism

In my journey to embrace my Judaism, I realized that we need the mimetic Jewish tradition, too.

Essays

A Letter to Children Estranged From Their Parents

Children cannot truly avoid the consequences of estrangement. Their parents’ shadow will always follow.

Essays

‘The Crisis of Experience’: What Singlehood Means in a Married Community

I spent months interviewing single, Jewish adults. The way we think about—and treat—singlehood in the Jewish community needs to change. Here’s how.

Essays

3 Questions To Ask Yourself Whenever You Hear a Dvar Torah

Not every Jewish educational institution that I was in supported such questions, and in fact, many did not invite questions such as…

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

Do You Need a Rabbi, or a Therapist?

As someone who worked as both clinician and rabbi, I’ve learned to ask three central questions to find an answer.

Essays

Between Modern Orthodoxy and Religious Zionism: At Home as an Immigrant

My family made aliyah over a decade ago. Navigating our lives as American immigrants in Israel is a day-to-day balance.

Essays

Do We Know Why God Allows Evil and Suffering?

What are Jews to say when facing “atheism’s killer argument”?

Essays

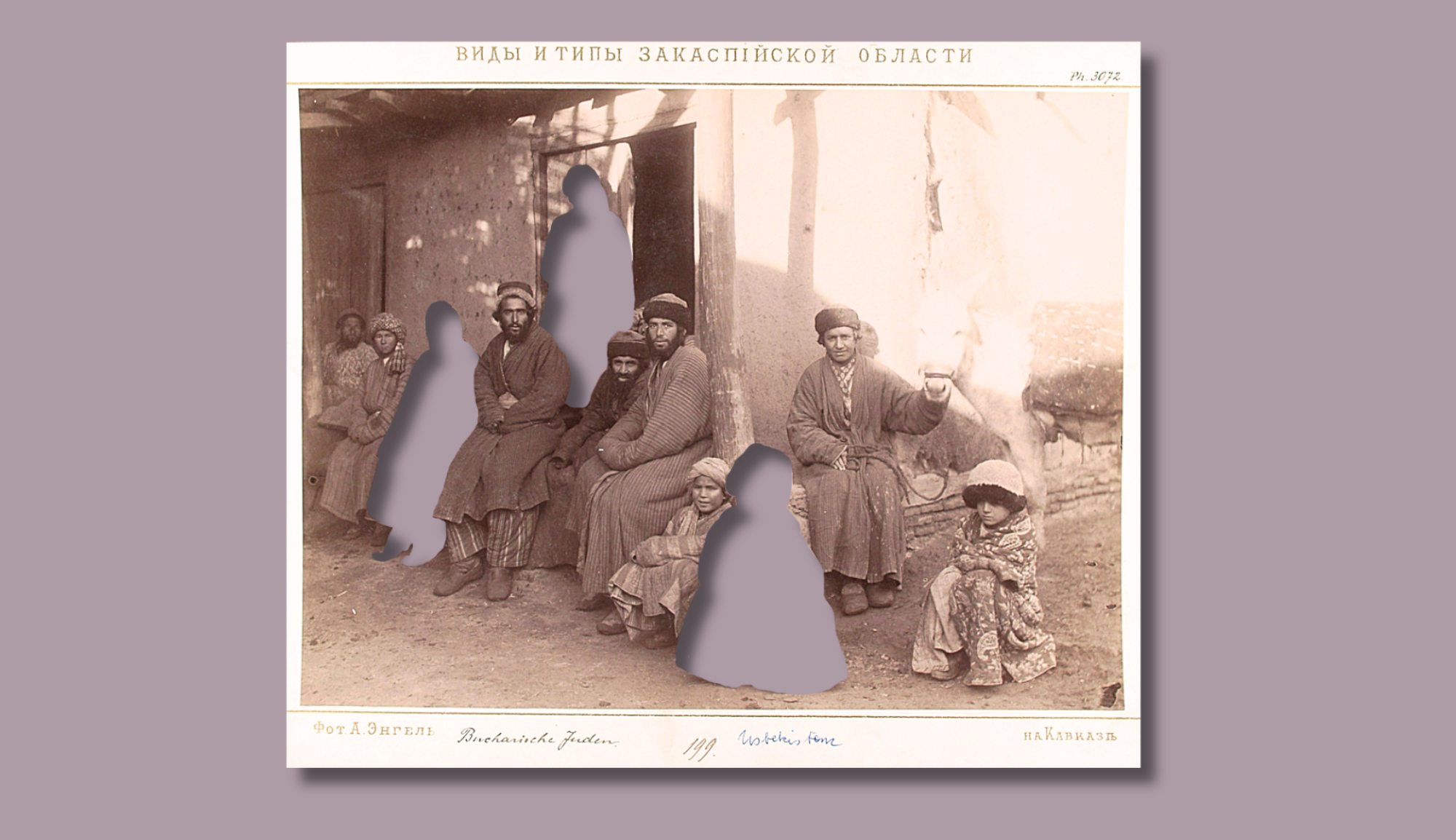

The Erasure of Sephardic Jewry

Half of Jewish law and history stem from Sephardic Jewry. It’s time we properly teach that.

Essays

From Hawk to Dove: The Path(s) of Yossi Klein Halevi

With the hindsight of more than 20 years, Halevi’s path from hawk to dove is easily discernible. But was it at every…

Essays

Judith Herman Is Giving Voice to Survivors

Dr. Judith Herman has spent her career helping those who are going through trauma, and has provided far-reaching insight into the field.

Essays

‘Are Your Brothers To Go to War While You Stay Here?’: On Haredim Drafting to the IDF

A Hezbollah missile killed Rabbi Dr. Tamir Granot’s son, Amitai Tzvi, on Oct. 15. Here, he pleas for Haredim to enlist into…

Essays

The Hardal Community Explained: Torah, Am Yisrael, and Redemption

Religious Zionism is a spectrum—and I would place my Hardal community on the right of that spectrum.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits’ Complicated Portrait of Faith

Meet a traditional rabbi in an untraditional time, willing to deal with faith in all its beauty—and hardships.

Essays

How and Why I Became a Hasidic Feminist

The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s brand of feminism resolved the paradoxes of Western feminism that confounded me since I was young.

Essays

When Losing Faith Means Losing Yourself

Elisha ben Abuyah thought he lost himself forever. Was that true?

Recommended Videos

videos

Mysticism

In a disenchanted world, we can turn to mysticism to find enchantment, to remember that there is something more under the surface…

videos

18Forty: Exploring Big Questions (An Introduction)

18Forty is a new media company that helps users find meaning in their lives through the exploration of Jewish thought and ideas.…

videos

Talmud

There is circularity that underlies nearly all of rabbinic law. Open up the first page of Talmud and it already assumes that…

videos

The Hasidic Rebbe Who Left it All — And Then Returned

Why did this Hasidic Rebbe move from Poland to Israel, only to change his name, leave religion, and disappear to Los Angeles?

videos

Did Judaism Evolve? | Origins of Judaism

Has Judaism changed through history? While many of us know that Judaism has changed over time, our conversations around these changes are…

videos

Jonathan Rosenblum Answers 18 Questions on the Haredi Draft, Netanyahu, and a Religious State

Talking about the “Haredi community” is a misnomer, Jonathan Rosenblum says, and simplifies its diversity of thought and perspectives. A Yale-trained lawyer…