Like most, I was introduced to Gary Gulman’s comedy with his incredible set on Conan, imagining a documentary about the naming of the states.

I watch a lot of comedy, but this set struck me as different. You could sense his love of language and his folksy decency. I became an instant fan. I watched some of his earlier sets about trivializing Hitler, discmans, and Trader Joe’s. Of course I laughed, but I was also struck at his ability to weave meaningful stories from the overlooked minutiae and frustrations of life.

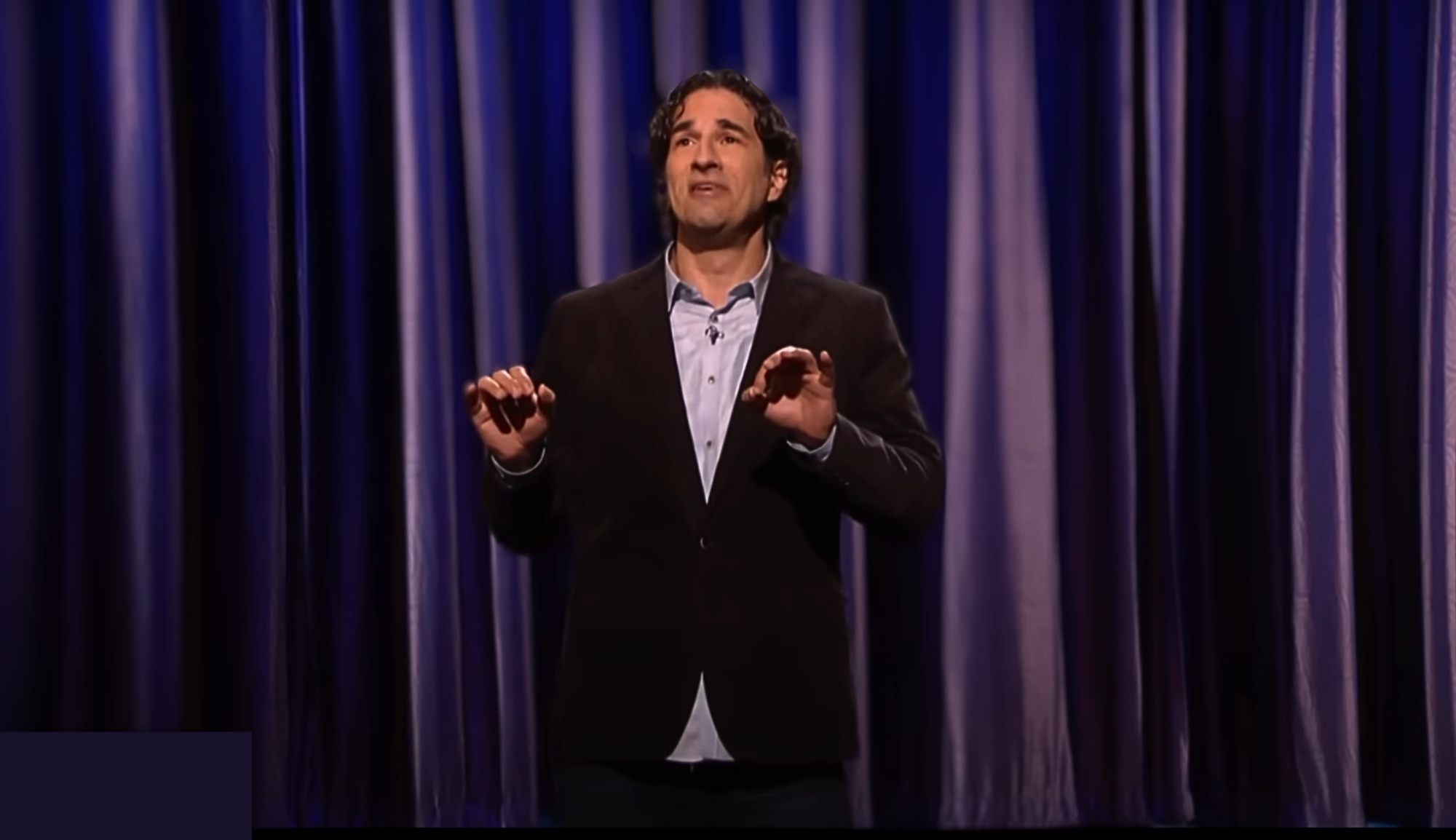

Then his comedy changed. Unbeknownst to most viewers, Gary suffered through a very challenging mental health episode. Performing a comedy set on Colbert, without mentioning the word depression once, he spoke about living with depression. With imagery of fork prints in ice cream and unchanged Brita filters, he vividly describes a life in normalized chaos. “I know your world,” he says—mostly in jest but also revealing the deep sense of empathy evident throughout his work. “I know your world,” I understand completely how the smallest task of replacing the toilet paper on the holder seems insurmountable. “I know your world,” because I live it. His comedy transformed into something more than comedy. It became a way to discuss some of the most painful parts of daily life. “The thing they don’t tell you about life is this,” Gary says plaintively, “life: it’s every, single day.” You can feel his words getting heavier as he says “every, single day.” In 2019, he released The Great Depresh, a charming, inspiring—and of course hilarious as always—special on HBO, about his battles with depression and mental health.

At some point, through a rather circuitous and fortuitous chain of events, I not only became a fan of Gary—I became a friend. He became a mentor and role model for how to lead a more empathetic life and, most of all, how to become friends with yourself.

I don’t have an HBO special, nor is one in the works, but I have spent years writing comedy, albeit on a much much smaller scale. My most significant contribution to comedy has been talking about what kind of shirts Jews like to wear (spoiler: It’s Charles Tyrwhitt). So, I have a way to go. But there is something about the process of comedy and personality of comedians that reveals a tremendous amount of doubt and insecurity. It’s an industry built on soliciting a reaction. And in a world where you’re constantly beholden to an audience’s reaction, it can become easy to equate their reaction with your self-worth. It’s a phenomena present within nearly every industry, but I think it is far more acute in comedy.

Great comedy serves as a level of sorts—finding the perfect balance between tragedy and monotony to transform life into meaningful commentary.

In 2019, Gary spent the entire year tweeting a daily tip on comedy writing. I once asked Gary over lunch if he ever considered becoming a full-time professor or teacher. I loved his response. “I think what I do now is teaching,” Gary explained. Comedy makes us laugh, but it also elucidates how we see the world.

In the 2002 documentary, The Comedian, which follows an established Jerry Seinfeld and a young comedian named Orny Adams, there is a moving exchange between the two about the anxieties of the profession.

Orny, ever impatient, complains to Jerry about how his friends in other industries are moving up and he feels left behind. I was always struck by the scene because in many ways I have felt the very same doubt Orny expresses. Not as a comedian, but as an educator. You watch your friends establish careers, make partner, find stability, and—as the funhouse mirror of life often reflects—your own life accomplishments feel out of sync. It’s an insecurity that is far more universal than comedy. It’s about the role of our professional accomplishments in our personal identity. What do you do?, Americans are fond of asking in open conversation. Jerry Seinfeld’s response is dismissive and marvelous: “Is there something else you’d rather have been doing?” Jerry seems comfortable embracing the unknown, the chaos, the confusion of the industry, as Orny struggles to superimpose a more sequential and predictable narrative on an otherwise chaotic profession. While Orny is trying to make it in show business, Jerry fell in love with comedy.

And within comedy one can find profound love, depth, and meaning. During the height of the pandemic, I was asked during a panel session, what do you do to find stability? I responded, I listen to comedy. Great comedy serves as a level of sorts—finding the perfect balance between tragedy and monotony to transform life into meaningful commentary. As I once shared in an article about my love of comedy, I learned about the value of comedy during a funeral. My friend, Josh Grajower, shared the following at his wife Dannie’s funeral:

When we came to New York for Sukkos, unfortunately we had to go straight to the ER. When realizing we would be stuck in the hospital all Shabbos, just the two of us, I grabbed two books to read. The first was Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. Yes, an intense choice. It was actually Dannie’s copy of the book and she had underlined certain parts. One thing she underlined was a comment Frankl made about the surprising role of humor in concentration camps. He wrote the following lines about humor, and they were some of the few lines underlined by Dannie: “It is well known that humor, more than anything else in the human make-up, can afford an aloofness and an ability to rise above any situation, even if only for a few seconds… The attempt to develop a sense of humor and to see things in a humorous light is some kind of a trick learned while mastering the art of living.”

Gary’s HBO special was produced by Judd Apatow, a major figure, to say the least, in comedy production. Judd was a student of the late Garry Shandling, a comedic visionary perhaps most well known for his HBO show, The Larry Sanders Show. Garry, fittingly enough, passed away on Purim of 2016. Judd produced an incredibly moving documentary on Garry’s life called The Zen Diaries of Garry Shandling. The documentary is based upon snippets from Garry’s actual diaries he left to Judd after he passed. It’s a moving testament to the inner struggles of comedians, and more generally human beings, grappling with finding centeredness and fulfillment in their lives. Garry was a master comedian, but, as often is the case, was plagued with self-doubt and insecurity. He was perpetually trying to overcome those insecurities with his professional achievement and fall in love with comedy. In a passage where Garry is grappling with comedy during a particularly dark period in his life, he writes to himself:

Maybe your comedy is a natural gift to be given to others with joy to help them through this impossible life and you sharing it, with no desire of getting anything back.

And maybe that’s the gift of comedy. It’s given to an audience with love and, if done correctly, it can only be for the smile—never just for business. Because the only way to make others smile is to share with joy. And that, even for only a few seconds, can help us through this impossible life.

Listen in to our episode with Gary Gulman.