Anonymous: Searching for the Beginning

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to an anonymous email sender about life upon the bridge between the truth of fact and the truth of feeling.

Summary

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to an anonymous email sender about life upon the bridge between the truth of fact and the truth of feeling.

Our anonymous guest sent an email in to 18Forty, which we read previously on the Malka Simkovich episode. In his email, he describes struggling with the Oral Torah and clinging to his faith despite the unknown.

- How has practical Jewish religious observance evolved since the canonization of the Oral Torah?

- Are the struggles of modern day Jews the same struggles Jews faced in the Second Temple period ?

- Where does the divinity of the Jewish People lie?

- Is Judaism intended to be a socially arbitrated system?

Tune in to hear a conversation on authenticity within spirituality.

Interview begins at 16:39

References:

Torah Musings Blog by Gil Student

18Forty – “Malka Simkovich: The Mystery Of The Jewish People”

Zakhor: Jewish History And Jewish Memory by Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi

Stories Of Your Life And Others by Ted Chiang

Exhalation: Stories by Ted Chiang

18Forty – “Moshe And Asher Weinberger: Heart Of The Fire: Together Even With Small Differences”

18Forty – “Larry And Tzipora Rothwachs: Here Without You — A Child’s Eating Disorder”

18Forty – “Andrew Solomon: Far From The Tree”

“Welcome To Holland” by Emily Perl Kingsley

18Forty – “The Legacy Of Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks”

18Forty – “Chaim Saiman: Is Talmud The Jewish Constitution?”

18Forty – “Ari Bergmann: Talmud As An Agent Of Chaos”

18Forty – “Joshua Berman: What Should We Believe?”

“Is It Really the Torah, Or Is It Just the Rabbis?” by Tzvi Freeman

Josephus: The Complete Works by Flavius Josephus

From Text to Tradition, a History of Judaism in Second Temple and Rabbinic Times: A History of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism by Lawrence Schiffman

The Rambam’s Introduction to the Mishna

The Thirteen Principles of Torah Elucidation by Rav Yishmael

The Shulchan Aruch by Rabbi Yoseph Karo

“Left and Right Brain Judaism” by Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks

COVID responsa from Rav Herschel Schachter

18Forty – Intergenerational Divergence

Mishna Berurah by Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan

“Rupture and Reconstruction” by Haym Soloveitchik

Judaism Straight Up by Moshe Koppel

Sin-a-gogue: Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought by David Bashevkin

Discovering Second Temple Literature: The Scriptures and Stories That Shaped Early Judaism by Malka Z. Simkovich

Outside the Bible: Ancient Jewish Writings Related to Scripture by Louis H. Feldman

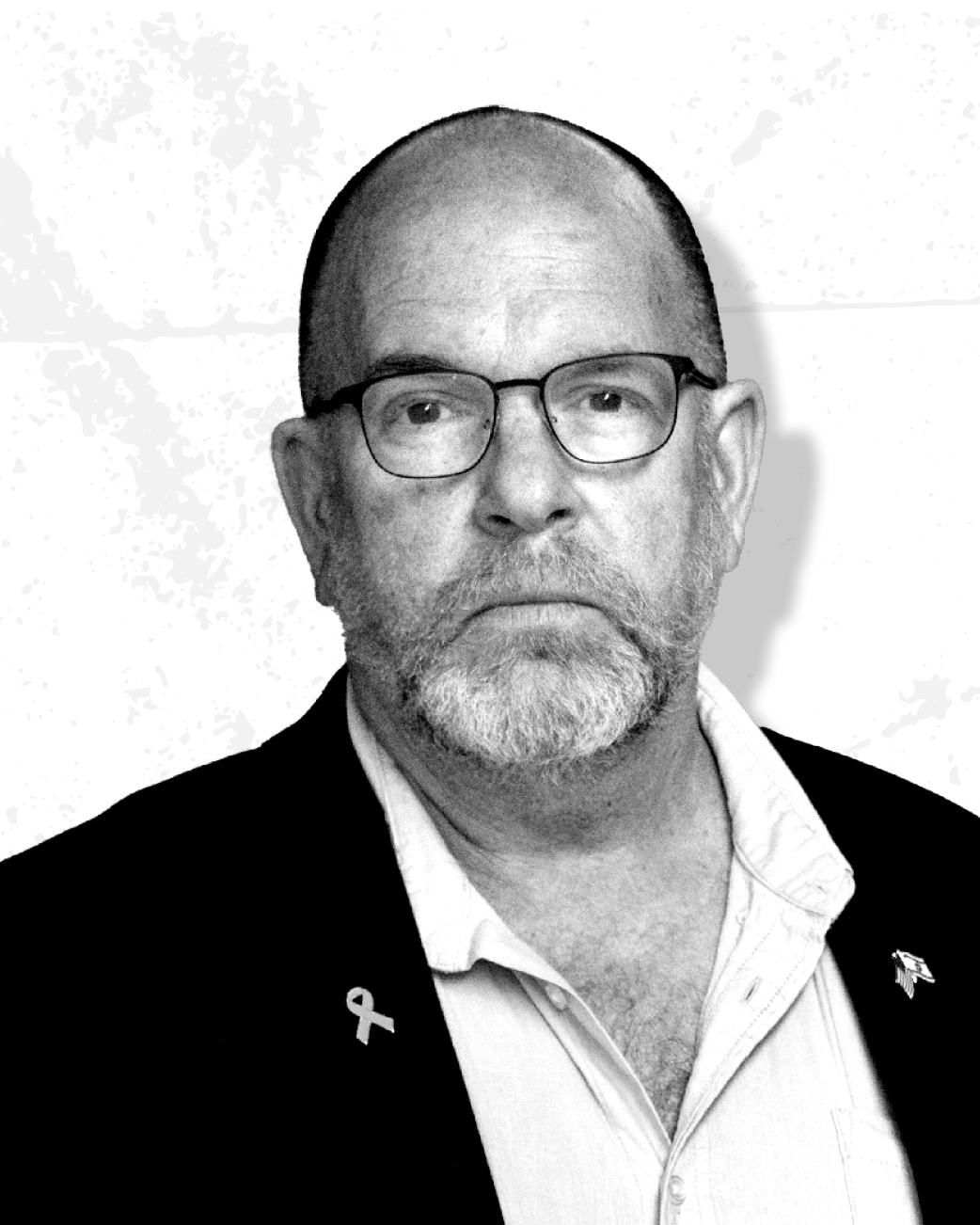

David Bashevkin:

Hello and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast where each month we explore a different topic balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host David Bashevkin, and this month we’re exploring the origins of Judaism. Sheesh. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big juicy Jewish ideas. So be sure to check out 18forty.org where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails. I feel like I need to explain a little bit the topic that we chose for this month. It definitely seems quite intense for many. It may seem a little bit controversial, but as we’ve mentioned so many times, what we do at 18Forty is address points of dissonance, points of friction in people’s religious lives, emotional lives. And I always break it down in my mind of these three points of dissonance.

Three areas that people find their relationship with religious life, religious community, religious commitment, somewhat wanting where they feel some point of tension. And those three areas are theological dissonance, sociological dissonance, and emotional dissonance. We spend a lot of time talking about emotional dissonance, where your Yiddishkeit, Judaism in your life is not giving you the satisfaction that you need, is not giving you the joy that you once had hoped it would provide. And we also spend some time talking about sociological dissonance. Sociological dissonance might be looking around at the community that you are a part of and wondering why they treat certain people in a certain way or the values that are preserved in the community are no longer ones that you feel comfortable with. But there’s a third type of dissonance, one that honestly doesn’t lend itself as easily to podcast conversations. And that is theological dissonance, where the very underpinnings, the very foundation of your Jewish belief and Jewish thought feel like they are built on shaky grounds.

And there is an aspect of theological dissonance that I’ve had so many people reach out about and I felt like it was necessary, even to talk about any of the other points of dissonance, whether it’s emotional or sociological, to at least dedicate some time to talk more about this and develop some sort of approach to understand how the Yiddishkeit, the Judaism that we know today relates to the Judaism that has existed throughout time. Basically what is known, what scholars would call the emergence of rabbinic Judaism. Now that’s obviously a loaded term cause some would say rabbinic Judaism is Judaism and we’ll of course address that. But the underlying question that we’re really trying to explore is how does the Judaism, the Yiddishkeit that I practice day to day, the Sukkos, the Yamim Tovim, the Shabbos, all of the rituals, all of the rights that are involved in Jewish life on a day-to-day basis, how does that relate exactly to the Judaism we see depicted in Chumash, the Judaism that we see depicted and told in the Torah, in the writings of the Neviim and Kesuvim, the prophets and the later writings, like it doesn’t always seem to cohere.

And how do we draw a straight line from that Judaism to the Judaism that we know today? This is a deeply essential and theological topic. It’s one that my partner in everything 18Forty Mitch Eichen always brings up to me. And I used to dismiss him more cuz it’s not something that I ever found particularly vexing. But for him, he always like would ask me is like why is our Jewish life now any more than the Raccoon Lodge is what he calls it, Which I forgot what TV show or whatever it is that he’s coming from. It’s obviously not any sort of television or media that I grew up with the Raccoon Lodge. But basically like, look, it’s nice, it’s wonderful, but I, I don’t see the divinity in all of this. Like God revealed himself so to speak at Sinai. And then like there’s all this other stuff, all the later interpretations.

Where is the divinity in that? How do we draw a straight line from the Judaism that we practice today to the Judaism of Revelation, to the Judaism that we see discussed throughout the prophets, throughout the Neviim? Like there seems to be like a break and then a reinvention. So can we figure out a way to build that bridge? And I think in a lot of ways there’s a reason why we’re deliberately talking about this right now and that is every, I don’t know, it’s every couple decades you can feel the tectonic plates of authority beginning to shift. I think this is the second time that this has happened in my lifetime. The first time that I felt the very plates of authority, of the stories and ideas that we’re handed down beginning to kind of shift, kind of create this sort of friction was in 2004 when the internet really started to flourish with social media.

I think it was first with blogs and there were this plethora of Jewish blogs weighing in on Jewish belief in Jewish theology. And you had access to all of these ideas that you never really like heard discussed. I don’t know if you were alive in 2004. But I went to yeshiva, I went to high school, I learned in Israel and then I’m seeing these discussions online. A lot of this centered around the controversy surrounding the writings of Rabbi Natan Slifkin. A fascinating personality in his own right and deserves his own kind of deep dive into that entire story and his ideas. But in 2004 there was this like major controversy surrounding his writings and the way he approached science and Torah. And I think a lot of the controversy wasn’t just about what he said, but the way that the conversation was mediated through the internet where people had access to information that they never would’ve had before.

And you kind of felt the democratization of information slowly upend what otherwise would’ve been kind of an open shut case. Like this is not what my rabbi told me. This is not not what I learned in school, this is not what I learned in seminary or yeshiva, wherever it is. And all of a sudden you would access to all of these websites and blogs and ideas. I remember in 2004 I spent two months learning in Toronto in the Yeshiva Darchei Torah, which was run by Rabbi Eliezer Breitowitz. It’s really a high school, but they had a group of students from Ner Yisroel. It was really one of the most enriching experiences of Torah learning I ever had. We spent two months in Toronto studying the third perek, the third chapter of Brachos, and Tractate Sotahwith really some of my dearest dearest friends like, and I don’t mean dearest friends like in the podcast sense. I always get criticized, but like my actual childhood friends, people who I’m still in touch with on a daily basis and like who fashion then formed the person that I am today.

Really we were all together in Toronto. It was an incredible experience. I learned how to nap on Shabbosused to be a very anxious student in my base measure series. I was like nervous to take naps on Shabbos, like I should probably be learning or doing something else. I remember one of the stars who was with us at the time, I’ll just identify him by Aryeh, still one of my closest friends I remember it was Shabbos afternoon, and he like went back, he’s like, oh I’m taking a nap. I’m like, just like that. He’s like, yep, just like that. Taking a nap. He was out for like one, two hours, like a real good nap. And I don’t know, I was like worried about like really enjoying a nap too much on Shabbos afternoon. But that all changed in Toronto. But the reason why I bring this up now is because I remember in 2004 what we would do is we would go into the teacher’s lounge, which was like the one computer.

There were no smartphones. It was the one computer in the high school and I had internet access and I would read the blog of Gil Students I think at the time it was called Hirhurim now it’s called Torah Musings. And he was like every day there was just something else, a back and forth of how to really understand foundations of theology. And that conversation more than anything related to science and Torah was really about authority itself. And you felt people began to like question like we have access to so much more. I’m gonna begin to question things that I never would’ve questioned. And there’s this sense of like what wouldn’t call it a crisis of faith, but you kind of sometimes feel the rug pulled out from underneath your feet when the people who you thought were unquestionable authorities. You see like wow, like there’s a lot of discussion about these ideas or positions that I had once upon a time taken for granted.

And I think we went through another one of those. And my guess and I, this is obviously only anecdotal, I could only surmise from the conversations that I have from people who’ve reached out through 18Forty and I know through my own life I think we went through another tectonic shift in authority during Covid, we never did a Covid reflection episode. Maybe we should have, I feel like most people don’t even like speaking about it. I’m not here to talk about the pandemic, but I am here to maybe suggest that part of people’s experience during the pandemic was not just, you know, the questions of isolation and the medical risk. I think a lot of people found it very challenging in the way they related to authority itself. And I don’t just mean medical authority, I mean authority in general and that spread to the way that they relate to religious authority.

There were people who have been in my office who felt that the communities that they were positioned in were far too lenient, that people in here who lived in a community that just felt like they weren’t taking anything seriously. And there are other people who’ve been in my office who have been frustrated that it was far too strict. It didn’t make sense to them and different people, a little bit like Goldilocks. But what it really left everybody with was with this kind of tenuous relationship with authority. My trust in institutions and in authority has been shaken. You could feel the tectonic plates beginning to shift of how people related to authority itself. And I think for a lot of people during this experience, like it affected the way they think of religious authority and religious community, something which features quite squarely and features quite prominently in this conversation today.

And I think that when we reflect on our religious lives, so much of what we need to understand is where does authority derive from and how can we build that bridge that what is motivating and anchoring our religious lives is something that we are comfortable with, that we are healthy with, that we are willing to sacrifice for. Cuz if you don’t have that healthy relationship with authority itself, with commandedness, Yiddishkeit‘s always gonna be difficult. But it’s not gonna be about sacrifice. It’s gonna feel like you’re being put upon, it’s gonna feel like you’re part of a social club with tenuous rules rather than a covenantal community rather than a religious community. Rather than preserving Knesses Yisrael and Amcha Yisrael, the great narrative of the Jewish people that unfolds throughout all generations. And in a way I wanted to begin with an anonymous conversations. We’ve done them before.

We’ve had several anonymous conversations. We had one that we did in our series on rationality, which you should absolutely check out. We had one that we did during our series on agunot that you should absolutely check out. And I felt the right way to begin this was with an anonymous conversation to hear from somebody about how this subtle shift in the tectonic plates and it’s not about one’s personal opinions during the pandemic, it’s how that experience shifted people’s relationship with authority itself. And that’s why I am so excited to, I’ve invited somebody who you’ve actually heard from before. There was an email that I read during our series on rationality in the introduction to our episode with Malka Simkovich that was extraordinarily popular and provocative but it began with me reading an email that we never quite answered. And I invited the person who wrote this email preserving his anonymity.

Not because it’s so salacious of who this person is or so controversial or herital but because I think sometimes listening to somebody anonymously helps you kind of be able to better reflect your own story and your own doubts in their own and not hand wave and dismiss it like oh it’s cuz they went to the wrong high school, the wrong yeshiva, the wrong wrong elementary school, the wrong parents, the wrong community. It has nothing to do with that. I mean there are real doubts and real struggles that people have with constructing their faith and there’s real theological dissonance that we oftentimes confront and we scratch our heads and like where do we find the divinity in our contemporary practice? Or is it just like a kind of a social club? It’s like a golf club where like it’s nice like you can put on a formal jacket if you want to join the club but like there’s no divinity in all of this and people really struggle and grapple with that.

And I’m hoping over the course of this series we can shed some light And ultimately I think this is about building a bridge between Jewish history and Jewish memory. It’s a famous distinction that was said by Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi his book Zachor, which draws a distinction between kind of the actual historic trajectory of the Jewish people, what actually happened so to speak, and the Jewish memory that we preserve the distinction that we’ve mentioned before, and I have no doubt that we will come back to, but I actually want to talk about building that bridge through a different lens. And if you’re still listening to this overly long intro, don’t stop now cuz I’m about to make a book recommendation to an author that will absolutely change your life. And that is the author Ted Chiang. Ted Chiang is a science fiction writer and he has a few short story collections and you know, if I’m recommending you a science fiction writer, it’s gotta be good.

I don’t read, I don’t read any fiction. I, I just don’t. I have no time for it. I don’t have that much interest in it. But there is one writer who I read everything that he writes and that is Ted Chiang whose collections are called The Stories of Your Life. And there’s a second collection called Exhalation. One of his stories I believe was made into the movie Arrival starring Amy Adams. But we’re not talking about that story now. Do yourself a favor. If you’ve never listened to a book recommendation, an author, ever, ever, do yourself one favor, buy a collection of Ted Chiang’s stories that’s T E D C H I A N G. He is not Jewish but his stories have deeply religious themes to them even in their title stories called Hell is the Absence of God. The 72 Letter Name of God is the title of another one.

He writes about mystical themed kabbalistic themes. Biblical themes, he has a story about the Tower of Babel and this story is absolutely fascinating. It is about a world where we are able to remember everything and the name of the story is the Truth of Fact, The Truth of Feeling, and this can be found in his collection Exhalation. The Truth of Fact, The Truth of Feeling ends with what I think is a fantastic passage about building that bridge between history and memory. He writes as follows, “We don’t normally think of it as such, but writing is a technology which means that a literate person is someone whose thought processes are technologically mediated. We became cognitive cyborgs as soon as we became fluent readers and the consequences of that were profound. Before a culture adopts the use of writing when its knowledge is transmitted exclusively through oral means it can very easily revise its history.

It’s not intentional but it is inevitable throughout the world. Bards and griots,” I don’t know how to pronounce that world G R I O T S, maybe Mel Baronholtz will call in. “Bards and griots have adapted their materials to their audiences and those gradually adjusted the past to suit the needs of the present. The idea that accounts of the past shouldn’t change is a product of literate culture’s reverence for the written word. Anthropologists will tell you that oral cultures understand the past differently. For them their histories don’t need to be accurate so much as they need to validate the community’s understanding of itself. So it wouldn’t be correct to say that their histories are unreliable, their histories do what they need to do.” And I think that’s such a fascinating concept that how writing has changed the way that we relate to history itself and that an oral culture, so to speak, almost the culture of Torah sh’baal peh the oral law, allows for a more fungible and flexible memory of our origins.

And I guess what we’re trying to do in this series is build that bridge between the truth of fact and the truth of feeling. Being able to bridge the immutability of Yiddishkeit and Knesses Yisroel that we feel that we connect in an unchanging way throughout history, yet at the same time be able to integrate that with the historical notion of development throughout all the generations and being able to build that bridge between the truth of fact and the truth of feeling the immutable, unchanging history of writing with the more flexible preservation through memory is the bridge and the journey that I hope to walk on with you during this series. So without further ado our conversation with our old friend, the writer of that email. I wanna welcome a really dear friend and just ask how you doing? How you feeling about joining 18Forty today?

Anonymous:

Have to be honest, a little bit, little bit nervous. I’ve been listening to podcasts in general and 18Forty for you know, years now. Been my main medium of content consumption for years and 18Forty, you know, probably a year at this point and I’ve benefited a lot from it. I don’t know how much this conversation will benefit other people. I hope that it will.

David Bashevkin:

First rule of podcast conversations is you don’t get to think about or consider your listening audience like right now we’re just talking, and the audience will decide that’s with everything. We’re really just trying to re-approach cuz it’s one of the most moving and important pieces of correspondence we’ve ever had. It generated a great deal of responses and I really want it to begin by going through the email again. I’d like you to read it rather than me and then we’ll talk about like why you sent it. You have like a very sweet intro, which I actually love, but if it’s not terribly awkward, my main goal is to make sure this is as not awkward and cringe as possible for you. But I’d like you to read the email.

Anonymous:

Sure. Actually listen to it on the way here from the intro to the Professor Simkovich podcast where you read it, it hit me heavy. That was the first time that I had revisited it since I I guess wrote it or heard it on that podcast many months ago. So I will do my best reading it in that original voice of struggle. “Hey David, your 18Forty podcast have moved me admittedly quite unexpectedly and I wanted to express my gratitude. Thank you for having the difficult necessary conversations I didn’t know I needed to hear. This was supposed to be a ten second email that then turned into a megillah. Apologies, it’s therapeutic for me to write this as if someone is going to read it. No pressure at all to read beyond here and I’d appreciate it if you kept it between us as I’m not very open about this aspect of my life.

I guess I feel a kind of kinship with you via your podcast as odd as that may sound. I became aware of 18Forty when you launched the idea of it in an email blast from NCSY but resisted consuming any of your content despite it being repeatedly referenced by friends over the years. Most likely it was out of arrogance. I thought I was smarter, more open-minded, more worldly than the people recommending your content to me I lacked and maybe still lack humility. I’ve been working on shedding arrogance, particularly when it comes to my relationship with the religion. I guess I thought 18Forty was just another attempt by Orthodox Jews to mimic successful secular content creators who have built loyal fan bases by having difficult, curious, honest, intelligent conversations. And I was skeptical it could be done in our world. I was wrong. The first podcast that I listened to were Rav Weinberger and his son and Rabbi Rothwachs and his daughter and those really moved me.

Those two podcasts are pure, brought me to tears, I rewound and re-listened. I identified with so much in each interview. I felt similarly in the interview with Andrew Solomon in the conversation with your ger v’toshav metaphor. I think that was the interview with him. And your reading an application of the Italy Holland poem to any of life’s experiences, which straight up caused me to cry. You’re an excellent interviewer, which to me is the hallmark of a great podcaster, asking the right leading questions and get out of the way. No instinctively went to follow up on an interviewer when he says something unclear or questionable instead of just moving on to your next scripted question and interject with your own thoughts, opinions, when it adds value, not just to hear yourself talk, but only after your interview has finished his thoughts. I admire this in you as I do in Bari Weis, Shane Parrish, Megyn Kelly, and to a lesser extent Joe Rogan and Lex Fridman.

People are gonna figure out who I am based on my interests in podcasts. So I started listening to your archive, The Talmud series, the biblical criticism series and your interview with Jonathan Haidt about Rabbi Sacks’ legacy. I have great respect for Haidt and have always felt deep admiration for Rabbi Sacks from his writings and talks. Had I been further along on the journey I described below years ago, I would’ve loved to have reached out to him about it as well. There’s a lot more in your archive that interests me and I’m very much looking forward to listening. There is one topic I’ve personally been struggling with for quite some time now and has impacted me on both a spiritual and practical religious level. I bring this personal vulnerability up with you, basically a stranger because two of your interviews briefly touched upon it and I was hoping would expound upon it but didn’t.

First for me was your interview with Chaim Saiman where you mentioned that the early Christians were already questioning Torah she’baal peh, and the focus on laws and ritual. I know little about that period and your interview with Ari Bergmann where you guys discussed how people were given the authority to apply meaning to the Torah, to use specific rules to extend rather than invent the law. The Chaim Saiman interview scared me, am I an early Christian? And the Ari Bergmann interview left me wondering how someone so intelligent learn it and honest sounding, I don’t know him could make that assumption without providing some sort of grounded basis for it. I just thought it begged to be explored more and was hoping you’d ask him more about that foundational belief but you didn’t. But that’s probably my bias because my current journey, here’s where I’m at. I believe in God without proof of his existence.

I believe in the divinity of the Torah without proof of its divine origins. I have not yet been able to articulate why I believe in those things, but it’s likely a combination of a pintele Yid, chassidus in general is something I have a weird relationship with. But I don’t know how else to describe the feeling about God and the Torah and the chosenness of the Jewish people. And two, the complexity, awesomeness, a novelty of the Torah similar to how Rabbi Josh Berman described the revolution of the Torah in its historical context on your podcast. But I never really articulated it that way before. More just had a sense of how it’s either created by God or renaissance man in a cave. And the former seems more likely to me because I’m skeptical a human could create it. I struggle with the authority of the rabbis, whether that authority is divine or as a sort of populous movement created by the people for the people. I generally struggle with authority, rabbinic or otherwise. I don’t care for people who unilaterally tell me what to do or how to live. Covid was obviously difficult for me. So I’ve been on a journey of trying to get to a belief that the practical Orthodox Judaism we know today is what God wants and is intended for. I’m not convinced that’s the case as I’ve explored this topic. I think what the core of the issue is for me is a believing in Torah she’baal peh being given at Har Sinai along with Torah she’bchsav, and B the unbroken chain of transmission of that Torah she’baal pehuntil it was codified and canonized in the Mishna, Talmud, and beyond. As a parenthetical, I understand there are many facets of Torah she’baal peh. The 1906 Jewish encyclopedia categorizes it into eight different groups. So there may be different explanations to each and I may be willing to accept that some of these were actually given at Har Sinai, i.e. explanations for things in the Torah that could not be understood without them or where the Torah seems to reference a prior knowledge or understanding of laws and explanations.

There are other parts of Torah she’baal peh that are more difficult for me to accept as divine, things that are more quote unquote novel. I’ve been trying to understand this historical context of Torah she’baal peh, what was known and debated in practice prior to its canonization? What did practical Judaism look like? If Torah she’baal peh was passed down from Har Sinai I would think our practical Judaism would look more similar to what it did in ancient and medieval times. Is it, for example, was Shabbos then what it is today? Or was it that you just couldn’t walk too far, you couldn’t light a fire, you couldn’t carry, you couldn’t do your weekday work. But the 39 melachos learned from the melacha in the Mishkan were not quote unquote assur. Because of my cynicism and skepticism of authority, I put together a story in my mind of how a practical religion may have been conceived by genius power rich rabbis who are looking to protect their way of life.

Basically the Prushim were battling with other Jewish sects for primacy in the Second Temple and post-Second Temple times. Different sects had different beliefs as to what was divine and what wasn’t. What was central to the religious experience and what was just fringe. The battles were in their interest of power and control over a religious population that was dealing with external, non-Jewish influences. And each sect had different ideas about how to deal with those influences. For a variety of contextual circumstances the prushim won, whether that’s because of the influence of Roman leadership, other sects assimilating into other cultures, geographic dispersion, et cetera. And they won, despite them being a relatively small group of Jews, the leaders of the Prushim became known as the rabbis and they claimed to represent the interests of the middle and lower class of people, not the elite noble priestly Jews who led other sects that may have been more Temple ritual based i.e. upper class.

And they had a dilemma. How do we make sure that what happened to the other sects doesn’t happen to us? How do we ensure Jewish continuity without the Temple and a central place of worship and community at the same time? How do we make sure that wherever Jews go, they’ll be resistant to Christian and Islamic influences? Let’s codify the religion. Let’s create a set of rules that we can tie back to the Bible through hermeneutical principles that may have existed in other intellectual cultures to create a daily, monthly, and yearly schedule of ritual and practice so the religion pervades every moment of life, and let’s say that the hermeneutical principles were passed down from God at Har Sinai and that the Torah actually gives us the power to do all this so we cover our bases. This is all true. It’s ingenious and deserves admiration.

I could even understand that people would be willing to follow it religiously, but for me, as someone who is skeptical of authoritative figures and probably too skeptical of human nature and human goodness that needs to be explored in intensive therapy, this gives me great pause in accepting so much of what has become front and center in our religious practice and makes me constantly uncomfortable and phony living the life I’m living. I make all the typical rationalizations to keep doing what I’m doing or religious Jewish community as a whole. It’s a moral, ethical, and socially charitable environment to raise my kids and live myself. So I put on tefillin, I sometimes chant the actual words of tefillah as prescribed by the rabbis. I find myself meditating and talking to God directly usually. I go through the annual holiday rituals, some of which are more meaningful to me than others.

But I do all this with a sense of being dishonest. I’ve spoken to one rabbinic friend about this and he said in a loving way that he thinks the arrogance which I’m projecting onto the rabbis is, well, a projection that I’m arrogant thinking I know better than the original rabbis were ill-intentioned and that they deviated from the divine script even if they were doing something right just by saving the religion. And that the way history has played out that we exist today as Orthodox practicing Jews in the numbers and population and various geographies that we do, shows that we are a People of the Book both biblical and rabbinic. That the education and Torah she’baal peh centric religion we’ve become is true and divinely ordained and couldn’t exist today if not for the hand of God directing history through the prion and the rabbis and the canonization of religious practice and the shift of focus from the Temple to education, et cetera.

I have not yet accepted all this. It doesn’t satisfy me. I’m looking for something more concrete, something more historical, something to dispel my conspiracy theory about what actually happened and a better understanding of what biblical religious practice looked like. There is one thing I found this week in an article by Rav Tzvi Freeman on chabad.org where he says almost as a parenthetical that the difference between the Sadducees and Pharisees was that the Sadducees were an elite class removed from the common people, whereas the Pharisees were well integrated with the working class. Apparently this has its roots in Josephus. Most were working people themselves and this is why the Roman saw the Prushim, the chachamim as the only true representative of the Jews at the time and also deal exclusively with them. He says this is from Lawrence Schiffman from Text to Tradition. Essentially the perushim were a populous movement, which was revolutionary at the time considering the eliteness of the Sadducees and the class structure of Greek Roman and most other ancient cultures.

Is this accurate? If so, it’s worth me exploring further because it could help alleviate some of my concerns of the efforts being driven by basic human desires for influence and power either way. So I’m wondering if you can help maybe point me in the right direction. Number one, what are the earliest sources of the existence of Torah she’baal peh. Number two, what are the best sources for the divinity of Torah she’baal peh? Number three, what are the sources for the unbroken chain of transmission? Not just that it exists and is a fundamental belief in our faith, i.e. The Rambam intro to Mishna, Iggeres d’Rav Shrira Gaon… Four. What are the sources for the divinity of Rav Yishmael’s 13 principles of which basically all of Torah analysis and debate is based on, are these divine or were, were they appropriated from other cultures or created by the OG rabbis?

Does it matter? Five, are there accounts, Torah based or archeological or historical of what practical Jewish religious observance was like before everything was canonized? I know this is a heavy email covering many different topics and I have zero expectations for you to read it or address any of it. It was helpful for me just to formulate my thoughts and deliver it to someone with a thought that it would be read by someone much more scholarly than me. If you’ve gotten to this point. Thank you so much for reading regardless. Thank you so much for 18Forty. Keep having the difficult conversations.”

David Bashevkin:

That is really powerful. So a remarkable email. I’m curious like what it feels like returning to it. When did you send this?

Anonymous:

May 26 2022.

David Bashevkin:

We’re amost six months, more than six months away from when you sent it. What does it feel like reading that email?

Anonymous:

I listened to it in the car on the way here. I listened to your reading of it, which I enjoy better than mine. It’s definitely emotional. It brings up feelings that I guess I haven’t felt since I was compelled to write this email, which I think was at point in this journey that was really emotionally difficult for me. So it brings up a lot of those, those difficult feelings of a weight on my shoulders that was just crushing me and not knowing where to go, who to turn to.

David Bashevkin:

So I’m curious the context, I don’t mean to cut you off. Yeah. But a lot of this really has to do with the context. You know, I almost like challenge like to read the email and not hear your voice. And not hear my voice and just to read that. Like what kind of person does it conjure up? I know you, you’re overstating how little we know each other. We do know each other. I think if we would’ve seen each other pre 18Forty in the street, I think a head nod. What, what do you think it would’ve been?

Anonymous:

You said in the prior intro reading of the email that you, Oh I mentioned this, that you would’ve saluted me on that you do that sometimes. Some people, and it’s funny cuz I salute people all the time also.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, I think it would’ve been like a salute, it would have been a head nod, not a stop and chat.

Anonymous:

Probably not. Yeah,

David Bashevkin:

Probably not. Not not a stop and chat. Right. And also like

Anonymous:

It might have even been like, wait, is that, is that the person? Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

We would’ve known each other And also like I always thought you were much like not cooler, but you were just like in like a faster crowd. I always like assumed that like you were just like fast and the furious living your life. You know, you ascribe certain like manipulation or like behind the shadows like this like conspiracy that you mention. I’m almost like the inverse that when I bump into somebody who I feel like doesn’t appreciate what I do, I have like an inverse where they’re not these like power hungry manipulation. You must be like so shallow and not get it to not like appreciate and know what I do. Like I’m forced to do that because like otherwise then like you’re just looking at me with these like empty eyes.

Anonymous:

Oh God. So you looked at me, you thought of me as being fast and shallow. Yeah. And then you basically,

David Bashevkin:

Basically.

Anonymous:

I got it. Totally. And I thought of you as being nerdy and intellectual on the spectrum. Yeah, exactly.

David Bashevkin:

Exactly, exactly. We’re like both coming up with these theories and I feel like the theories that we come up with is like to find that like just base comfort and just like feel our sense of self intact without feeling either manipulated or undermined or inadequate.

Anonymous:

Well I saw I would push back, I don’t know if I’ve ever thought of myself as being part of like a fast crowd or fast crew.

David Bashevkin:

No. That’s my conspiracy theory.

Anonymous:

Right. Got it. That’s not true. The same in terms of like shallowness, which you’re saying is like your conspiracy theory. I think I’m in a place now on this journey that hopefully I’m humble enough to say that I think my approach to many things in life, including religion was shallow. That isn’t necessarily a projection or your just assumption. I think that was probably somewhat true about my approach to many things, life in general, but definitely religion and spirituality.

David Bashevkin:

So I’m so curious. Like I don’t listen to as many podcasts as other people because I’m usually busy creating what we do here. But I’m always so touched when somebody takes a time they listen to me when in the car, when they’re, you know in the home doing this, they’re doing this and then they take the time to not just like put down their phone and say like, hey thank you. Which is like beyond, but like you really wrote out and shared something and invited me to a very real honest and intimate place in your life. What exactly was going on in your life that compelled you to write such an email? Like you know, every high school, I don’t know every shul, every adult education like has that class, which is like introduction to the oral law where they tell you the basics what was given to Moshe at Har Sinai. Like one of those classes that I’m sure you some Shavuos night was like the 2:00 AM class or like the 12th grade, you know, intro. Why wasn’t that sufficient and what exactly was going on in your life that compelled you or made you feel enough tension to write an email like that?

Anonymous:

I definitely had experiences and classes over the course of my life and education, like you said, that went through the technical aspects of let’s say the oral Torah and not necessarily how it was developed in a very advanced way, but from point A, B, C D to today, how we get to where we are.

David Bashevkin:

It takes a pasuk, takes a verse in the Torah, then shows you like the Mishna…

Anonymous:

You even have certain principles that were potentially given by God at Har Sinai, from Moshe and then passed down. That allowed us to interpret those verses.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. Flows and very smoothly. It was very neat

Anonymous:

That was all floating around in the nether for hundreds or thousands of years until people woke up one day and said we need to write it down because even though it hasn’t been lost, but over the last thousand or so 1500 years, it could be lost in the future. So we need to write it down and make people obsessed with writings in books and all the, the written stuff and turn all the Jews into OCD characters and a novel. Sorry, that’s my skepticism.

David Bashevkin:

Little PS to to that story.

Anonymous:

I’m sure, I’m sure I’ll do that a lot in here. But I’m in my mid-thirties. We were coming out of Covid lockdowns in general. I think throughout my life I’ve struggled with authority, particularly when authority figures unilaterally tell me what to do without providing sound reasoning for it. I never liked whether it was parents, teachers, rebbeim, just people who were older than me who I was always taught to respect and listen to telling me what to do do if I couldn’t understand why I was supposed to do those things. And I think a combination of just getting older and you know, I know people go through midlife crises but maybe I could say that maybe have been going through a first third life crisis assuming that hopefully I have two more chunks of 30 plus years ahead of me. Yeah. God willing, God willing.

So I think the years of Covid presented me with like a lot of time to think about things that had been stirring in my mind previously for years but just didn’t have enough time to really think about and explore because of life, because of work and family obligations and just other competing responsibilities that were present, but not having a commute anymore. The world coming to an end, things being slower kind of gave me time to pause and think a little bit more about things that I’d always thought about and maybe wanted to pursue and learn more about but didn’t. And then that coupled with the unilateral authoritative messaging that came out during Covid from a health perspective, which really has little to do with religion, although it did begin to impact obviously our communal religious practice that is so central to what we do.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Anonymous:

I think that really triggered in me like I need to understand A why I’m being told to follow all these new health rules that seem to be coming on very strong. And there are some voices out there that are speaking up against the main principled voices that were out there but were being shunned and ignored and pushed aside. And also thinking about other parts of my life where authoritative figures influence that dramatically. And I think my religious life is really where that’s most present. I think I’m a pretty independent person and you know, I believe in traditional liberalism, you know, not the way the term has been co-opted today where you know, less authority, less government is just better. And I started to just ask questions in my head and to think about things.

David Bashevkin:

To me the strangest reaction is knowing you, and maybe I’m coming back to my own preconceived notion, is why don’t you do the regular thing that a person does in their thirties, which is like, just stop taking religious life so seriously. Isn’t that like the more common reaction? Like you see somebody, we have our years in yeshiva, you’re totally plugged in like it works, you know like from the ages of, I don’t know, 19 to 23 and then like you start work and you’re like, oh I’m gonna keep this up at like, I’m trying to remember like when you’re 22 years old, like how many hours a day do you think you’re gonna be learning Torah? You’re like at least one seder a day. Like one chunk, which is like three hours, which is like Herculean if you’re doing it like God bless you power to you and then like by the time you like exit your twenties, this like very neat, nice package.

It’s been beat up. It reminds me of that early scene in Ace Ventura Pet Detective, the first Ace Ventura movie when he’s being a FedEx guy and he’s delivering some FedEx and he like kicks the package and he’s like playing football with it, stuffs it in the mailbox. Like that to me is your religious life by the end of your twenties, which like in your thirties, a lot of people, and I’m not like advocating for this, but the reality is the questions and all the obligations you have in your life is like you just kind of reassess how seriously you take it. Those who are still taking it seriously is because like these questions maybe they don’t bother them as much but they don’t double down. Like if you have questions, usually you like take chips off the table, why didn’t you do that?

Anonymous:

So it’s a really good question and I think it’s important maybe for me to take a step back and just give you a little bit of like a background on myself, my upbringing and like how I got to this point in my life so that you understand a little bit more about why this was my approach to trying to figure this out as opposed to like you’re saying maybe just,

David Bashevkin:

Just be chill at like just, well

Anonymous:

What did we call it? Like chucking it That’s, we called it in yeshiva just chuck it.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, but not, you’re married-

Anonymous:

Oh obviously not. Not removing myself from the system because I have a whole life set up. But you can chuck it in a way that can can still be part of the system.

David Bashevkin:

I feel like chucking it is what you do in your like early twenties like right or

Anonymous:

Mid twenties at light. Right. Okay.

David Bashevkin:

I think what we do in our thirties, we we’re checked out, we’re checked out, we’re checked out. Like it’s a better term. You show up, you, you’re not even like, you’re not listening anymore.

Anonymous:

Although I think you’re right, it’s a different terminology for our thirties, but essentially it’s almost the same thing.

David Bashevkin:

Oh it’s same, same phenomena just at a later point in your life.

Anonymous:

But it’s the same thing.

David Bashevkin:

Because chucking it, there’s a certain way

Anonymous:

Chucking that you’re gonna end up marrying a very different type of girl. Exactly. Than the girl.

David Bashevkin:

You can’t chuck it once you start a family you can check out where it’s like just let the inertia of whatever decisions you’ve already made, like play out. Maybe you’ll run outta gas maybe, but like it’s like inertia, rundown. You’ll show up to the siddur party and like maybe that’ll put a little bit of gas and tap the pedal. Right. But you’re basically running on in terms of your own motivation, you’re running on fumes of decisions that you made 10 years ago. Right. That’s most people. Why wasn’t that the case with you? Take me back.

Anonymous:

So, so I’ll, I’ll start off just by saying I’m not a rule breaker. As defiant as I am of authority, I’m not a rule breaker in general. So at least that’s the way I see myself. But let me go back a little bit further. So I grew up in modern Orthodox community going to typical modern Orthodox elementary school, high school, two years in yeshiva before I went to YU in a, in a all the good market,

Anonymous:

All the good market,

David Bashevkin:

All brand names, the

Anonymous:

Whole way through brand names, you know, top yeshiva in Israel, top shiur in that top yeshiva in Israel.

David Bashevkin:

Were you in the top, top shiur in 12th grade?

Anonymous:

I started out not in the top, top shiur because I didn’t want that pressure. The in senior year I wanted to chill, but by like a month in, I think by like Sukkos time I realized that like I was accomplishing zero.

David Bashevkin:

So you leveled up.

Anonymous:

So I leveled up. I had been put in that top shiur originally,

David Bashevkin:

Cause you’re bright.

Anonymous:

The first day of school I showed up and I said I’m not going to that year I’m going to the one step down. And by Sukkos it was just like, I can’t, it’s just not working for me. So I, I did level up and I love the rebbi in that second level shiur and that was one of the reasons why I wanted to go into that shiur.

David Bashevkin:

Gotcha.

David Bashevkin:

And I have a tremendous amount of respect for him and he’s somebody that I would love to reconnect with, you know, and I see over the years and I always have very fond memories. We always reminisce together. I was really set up and then I went to YU after two years in yeshiva and you know, top shiurim in YU, serious relationships with my rebbeim and with those rashei yeshiva in YU, relationships with other rashei yeshivain YU, you know, I looked the look..

David Bashevkin:

Not black and white?

Anonymous:

Not black and white, but borderline like

David Bashevkin:

That refers to yeshivish white shirt and black pants. Right. That colloquially. Right. If you really like maxed out.

Anonymous:

But I was always tucked in like nice shoes, nice shirts, button down slacks. You know, I would never be caught in sneakers, God forbid jeans. Like I didn’t even at that point I had given away all my jeans from high school. Oh.

David Bashevkin:

I,

Anonymous:

Yeah. You had mentioned this in the past that jeans were like jeans

David Bashevkin:

For men in your early twenties. It’s a great cultural signifier.

Anonymous:

I can’t even, I can’t even describe pre myself wearing jeans. I can’t even describe what the taboo was like about jeans. It was like so not touchable if you, But when I put jeans on for the first time, the liberation that I felt, it sounds so silly. It was so freeing. But

David Bashevkin:

If your 20 year old self saw you now they’d be a little judgy?

Anonymous:

Not frum, this person cannot be frum.

David Bashevkin:

Your 20 year old self?

Anonymous:

Yeah. Completely based on like externals-

David Bashevkin:

Would’ve looked at you and been like bum. Like he would’ve chucked it.

Anonymous:

He completely chucked it. Like yeah. What is that yarmulke even doing on his head? Yeah. Okay. Yeah. I always tended to more casual other than those post yeshiva and YU years even in high school. And then after a bunch of years into my marriage, like I always tended into casual even during those yeshiva years, like the second I got home and was out of like the public eye, I put on shorts in the house, sweatpants. Like I never felt comfortable in like nicer clothing. And now I’m, I think I’m a little bit more authentic to who I am and I generally trend more casually out in public. Yeah. Also that was yeshiva and YU and this isn’t.

David Bashevkin:

This is not why we’re here. It’s so interesting how my early crises of faith, aside from the jeans, but one of my like early when you feel the suffocation of religious expectations, the earliest memory I have is the expectations of what you’re supposed to wear on an airplane.

Anonymous:

Oh that’s really interesting.

David Bashevkin:

Where there is an expectation and you see it on any airplane and this plays across gender lines in a very real way. This is where I think men have the short end of the stick. I think most expectations are gendered where women have a higher expectations and tougher expectations. I think one area where men have tougher expectations is what are we expected to wear on airplanes? I wasn’t in YU I was in Ner Yisroel, there was a sense that you’re wearing a button down shirt and a davening jacket and like even a black hat potentially. And like you’re dressed like a ben Torah, that’s the the terms, a ben Torah does not wear shorts. A ben Torah does not wear sweatpants. And I remember hearing a mussar schmooze like one of these talks in the dining room I remember was from Rabbi Tendler about the pain he had when he saw alumni of the yeshiva change out of their ben Torah clothes on an airplane. And I remember I’m like, oh gosh, like that is me. He knows that I am not there. And that sense of like material comfort, being comfortable in your own clothes can feel that sense of like you could get that suffocation like the tightness starts to wear. So you’re doing everything right. What happens? You don’t really kind of have like a crisis of faith.

Anonymous:

Right. Throughout this whole time. The way I think about about it right now is I never thought about the system that I was in. I always worked to perform as well as I could within the system that was presented to me.

David Bashevkin:

I love that meaning show me the rules. Show me what being above average or great looks like and I will perform to that level.

Anonymous:

Right? I thought that the way to live a meaningful spiritual God connected life was to follow the rules, to check all the boxes, to do all the things that I was told are what makes you a great God fearing person. And that means following these rules that were set for us, not finding God, that in itself was finding God, but there wasn’t this journey of actually finding God or having a relationship with God. It was studying the books, learning the laws, doing the things that you’re supposed to be doing. That is your connection to God. And to some extent I did that until I was, you know, probably 30 even through, you know, having kids and you know, the whole first half of my marriage, it was still-

David Bashevkin:

Your 30 year old self is going to minyan every day.

Anonymous:

Yeah. I had a few jobs that made it difficult just with the hours to, to go to minyan. But yes, like for sure davening three times a day. I would not miss a davening, God forbid never miss that.

David Bashevkin:

And are you learning, are you still like in the game, learning wise?

Anonymous:

So yeah, so definitely from 20 to 26, 27 I was trying to learn in the mornings before going to work on the commute to work, whether it was listening or learning something and then trying when I got home at night, setting aside time for learning and for sure on Shabbos not pursuing like secular things that I was interested in because there was no time for that. My daylight hours were spent working. So my non-daylight hours, my responsibilities were family and continuing to learn and read the books that make me a good Jew.

David Bashevkin:

And at some point you’re saying a lot of this has to do with Covid.

Anonymous:

I started to have questions before that. My first inkling of having some questions about it started in YU. But I think I really put it to the back of my mind. I took a class in YU, Professor Steven Fine.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Anonymous:

Who I loved. You know, I was a fresh back. That was the term that we used for the post Israel.

David Bashevkin:

Newly back from your gap year in Israel.

Anonymous:

Correct. My two gap years in Israel. Yeah. Even questioned whether or not I was going to pursue like a secular career or maybe do like smicha, rabbinic ordination after YU.

David Bashevkin:

Was that a consideration?

Anonymous:

For probably my first semester or two in YU? It was possible, but then I think I realized that I have no interest in spending my days with like kids.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, yeah,

Anonymous:

Yeah, yeah. So I quickly decided not to do that.

David Bashevkin:

And you sit in Steven Fine’s class…

Anonymous:

I sit in his class and it was a class, I think it was about Second Temple Judaism or post Second Temple Judaism and the Hellenization of Jews in, you know, different cities. And we went like city by city in ancient Greece or in Egypt in Alexandria and all different cities that there were, there was this exhibit in one of the museums in New York that we went to a bunch of times to see, you know, artifacts and things like that. And the textbook for the class was Professor Lawrence Schiffman’s from Text to Tradition. Sure. The Second Temple Judaism. I remember reading things in there that I had no idea that he was from. And particularly from reading the book, I still have a hard time understanding and I would love to know what his belief system is. Given the way the book is written, it seems that it’s, you know, it’s a very historical account of Second Temple and post Second Temple Judaism and seems to at least indicate, and in my mind now having reread it several times since then, and for that being almost like my Bible at this point, you know, in my journey, in my journey on this, it seems like God’s hand is missing in that book.

Everything that happened to the Jews during Second Temple and post Second Temple period in this book, which I don’t think is meant for like an Orthodox audience necessarily.

David Bashevkin:

No, it’s an academic, it’s an historical account.

Anonymous:

Seems indicate that the Jews and the evolution of Judaism was just a product of history. The Jews dealing with external influences that caused them to transform their Temple based religion into something that could outlast the Temple and geographic dispersion. And I, I think I had read that in YU and it maybe struck a chord with me, but again, I was a fresh back and I was learning three sedarim a day in YU, which I don’t think people give enough credit to. People who have a dual curriculum in YU and are learning three sedarima day. It’s madness. It’s six o’clock in the morning until 10:30, 11 o’clock at night every single day. And you’re in classes and and and then that’s classes the entire time. Yeah. Then you have to figure out a time to do work and to study. It’s madness. I learned three sedarim a day in YU, meaning when I, I had set my schedule up that I had at least an hour free every semester in the middle of the day between English classes so that I could

David Bashevkin:

Wow. I didn’t know you were that on.

Anonymous:

Well, yeah, afternoon seder. I was trying to learn like machshava and whatever, I don’t even know how I was in the beis medrash. I don’t know how meaningful that seder was. When the new YU beis medrash was built I was that seder I was always sitting on top.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, I remember.

Anonymous:

And I was just sitting there because I felt it was important to be in the beis medrash for three sedarim a day. But I kind of put that to the side and I think that always popped up every now and then. But I didn’t have time to process it. I didn’t have time to think about it. I didn’t have time to explore it. I was just so busy. I had really demanding jobs once I left YU, I got married right after YU, I had kids, you know, right away it was just, there was no time to explore.

David Bashevkin:

You’re on the treadmill in a lot of ways. Like we used the system, particularly in the tri-state area to our advantage where like, you don’t have to think about it because you could just kind of go into the system and, and you know, check in, check out how-

Anonymous:

I didn’t even think that there was something above the system to really meta system to think about. I thought like machshava and mussar were like, yeah, like you do it when you need some like lighter learning and when you can’t be learning Gemara and halacha and Shulchan Aruch, like you pick up a machshava sefer, you pick up a mussar sefer and like you do those things because it makes you well rounded. But like that’s not the meat and potatoes. Like that’s not what you’re there for. You’re there for all the other stuff. I did not appreciate that there’s not only a whole discipline, but there’s a whole, I don’t know if I wanna say alternate approach to connecting to God. Maybe this isn’t the point in this conversation to talk about what the primary way to connect to God is, but that there’s a lot of deep literature that’s accessible and really important for people to discover. Not in the traditional-

David Bashevkin:

Canon.

Anonymous:

Canon.

David Bashevkin:

Canon’s the wrong word, but I mean it like the canon of what you get in yeshiva,

Anonymous:

The Mishna, Gemara, halacha, rishonim, achronim, you know, sheilos and teshuvos…

David Bashevkin:

Before we get to your educational curriculum, which I do want to get to because you’ve kind of developed your own.

Anonymous:

So let get to the point that I think really that really brought it out. There was someone that I encountered for a bunch of years of my life who I spent a decent amount of time with, both in person and on the phone, who was very bright, knowledgeable, modern Orthodox Jew, who had a really deep knowledge both of, let’s say the traditional canon that we were just talking about, like mishna, gemara, Shulchan Aruch, But over time developed a real knowledge of skepticism and skeptical literature of the traditional canon. And I remember one day he presented to me like a timeline of Jewish history and basically pointed to all the cracks and holes in that timeline that would lead one to be skeptical of the unbroken chain of transmission. To be skeptical of the authority to let’s say expound and expand upon the written Torah.

David Bashevkin:

Was this a peer or somebody?

Anonymous:

No, there’s someone older than me. Extremely well read.

David Bashevkin:

Uh huh. Why are you talking to him about this in the first place?

Anonymous:

I think he liked to tease me that I was still, you know, plugged, plugged in eight years in and still doing all the things. Yeah. And following all the rules and not breaking anything. And you know, really like just a good boy. And it never got to me, like never ever caused me to once like think like I’m gonna break any rules. It was like there’s different ways of doing things. Like he’s more modern and you know, academic. And you know, maybe if I would pursue this stuff maybe I would agree, but like I don’t think there’s a value in pursuing it. I’m like there are many things in the world that could be true. I hard to say that things are in conflict with each other, are contrasted to each other, are both true. But you know, there are different ways of people of understanding. He’s still within the Orthodox world. He’s still within the religious world. In my mind it was just a different way of like practicing,

David Bashevkin:

But you basically ignored.

Anonymous:

It caused me to say maybe I should start looking into this at some point. Okay. Like he’s really smart, he’s really well read. And it’s not someone who’s just like super skeptical of everything. You know, we both have like analytical mindsets a little bit. It made sense to hear what he has to say and to potentially explore it at some point. The first thing that I did at that point was I picked up Lawrence Schiffman’s book and I started reading it because that was really like the beginning of the time period that I started to see some cracks in this-

David Bashevkin:

Major shift. Yeah. Second Temple Judaism. Yeah. Following the destruction.

Anonymous:

I definitely found a lot of the things that he was saying to be validated by the history. And that was compelling to me. Didn’t change anything practically.

David Bashevkin:

You’re still going to shul.

Anonymous:

Still going to shul.

David Bashevkin:

You’re still, you have a hot water earn on. Yeah. Yeah.

Anonymous:

To this day, like I’m not a rule breaker. Like it’s not-

David Bashevkin:

But the rules are intense. Yeah.

Anonymous:

Whether I find meaning in every single rule and halacha, like that’s a separate discussion. Yeah. But I’m not a rule breaker. Like these are part of our communal norms that we have and I find value in it in being a part of it. So I’m not gonna start breaking those communal norms. So that’s where I think it started. And this is probably a year or two before Covid and I really didn’t pursue it much more than just like, you know, I need to find time to really explore this. I have this book, I read it, I understand that the history of all this stuff is not so clear, but this never even reached into like my belief in God or my belief in the divinity of the Torah or my belief in like the Jewish people being chosen by God to represent him and to bring his presence into the world. It never got to that point. I have this, I guess, irrational, innate belief in that

David Bashevkin:

That always remains intact.

Anonymous:

Always. I believe it as like a fact. I believe it as much as I believe that I need oxygen to breathe in order to live. Yeah. Like I, I can’t, I’ve definitely explored theological arguments to maybe ground my belief in some sort of rationality, but I don’t necessarily look for something that’s 100% foolproof as a proof for God. I don’t think like that. I identify very strongly Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, alav hashalom‘s left brain, right brain distinction when it comes to like my belief in God. That’s right brain. You talk about it in like sometimes in languages it’s a different language of thinking when I think about my belief in God and I don’t need, you know, this fundamental, rational, historical

David Bashevkin:

Academic,

Anonymous:

Approach for that. But once we move into the human where now humanity had a major influence on the religion, now I need some sort of bridge to get me from my left brain to my right brain. You know, I need some

David Bashevkin:

Bridge to God revelation that transcendence. Yeah. To like the world we live in today. And so yeah,

Anonymous:

Around the same time that Covid hit, there were several controversies, scandals within the modern Orthodox community. The Orthodox community, both where I live and not where I live. And a lot of it had to do with the way local rabbis dealt with certain situations within the community.

David Bashevkin:

Local communal politics. Yeah.

Anonymous:

Yeah. And that added fuel to the fire. I can’t for the life of me understand why rabbis are making these decisions or these proclamations that they’re making so universally without a message of explanation as to why they’re telling us to do these things or not to do these things.

David Bashevkin:

And you’re taking all these local politics and projecting it back like, oh I see a preservation of power. You just wanna like keep the community in line and you’re taking all these local things that you’re seeing and projecting it backwards.

Anonymous:

Correct.

David Bashevkin:

2000 years essentially.

Anonymous:

And then obviously they got very heavily involved in Covid as well on a local level.

David Bashevkin:

I had a different reaction to you A, we don’t live in quite the same community and I actually liked the feeling of being locked down and cut off. It actually gave me like a feeling of stability. And when I started seeing responsa from Rav Herschel Schachter, I got like viscerally emotional, I almost started to cry because it was like, oh there’s a way to solve these issues. Those weren’t the issues quite that you’re talking about. You’re talking about like,

Anonymous:

Well even within Covid what you’re talking about, I also love the lockdown. I’m a hermit. No, but

David Bashevkin:

There was like shul battles. I don’t wanna get into all all those details.

Anonymous:

Yeah. When protocols started-

It got very, you couldn’t have a minyan, you know, with your neighbors where everyone’s standing on their lawn and you know, and your backyards are close to,

David Bashevkin:

I definitely don’t wanna relitigate whatever Covid right now. But there was a time where-

Anonymous:

Like, and and then they got involved in the whole vaccine conversation, which again we’re not relitigating Covid but to me that was probably the straw that broke the camel’s back for me was what are the rabbis doing, getting involved with people’s medical physical health and their medical needs. Not only are they not medical professionals, they’re being advised by certain medical professionals obviously, but they don’t know every single person’s individual medical needs and history to make a proclamation that every single person must get vaccinated and putting religious significance on it. Pikuach nefesh, halachic obligation to get vaccinated.

David Bashevkin:

So it just felt invented. You felt you were watching the invention in real time, so to speak.

Anonymous:

Everything that occurred and like post Second Temple Judaism was happening. Now we are creating new halacha for some potential agenda that I don’t fully understand but there’s clearly an agenda that’s driving this. And obviously, you know, I lean towards conspiracy theory.

David Bashevkin:

People are gonna get the wrong impression of you. You’re not like a tinfoil warrior.

Anonymous:

No, not a tinfoil hat.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. Just wanna be clear.

Anonymous:

Yes. Not tinfoil hat.

David Bashevkin:

Conspiratorial thinking. Not in the crazy like tinfoil hat. No. But the sense of like are people, like-

Anonymous:

Humans are driven by natural human ambition and that can pollute otherwise positive, noble motives. Correct. And we have to be aware of that in anything and everything we do. And there’s no class of person that is above natural human inclination.

David Bashevkin:

I so desperately want to jump in cuz I have some responses cuz I also, I’m deeply skeptical. I abhor the mixture of politics and religiosity. I find it repulsive and it’s something that we are struggling with across the board. There’s no safe haven from it. And I do see that like there’s somebody who lives on the other side of Teaneck named Pinny Stieglitz and we did a video in his house where he showed the regulations of an Italian, I think it was the 16th century Italian community and what they were regulating, it was like a broad side. It looked like something you would see hung up in Meah Shearim, and it had rules about what type of weddings you’re allowed to make.

Anonymous:

Yeah, I watched this video.

David Bashevkin:

And whether or not you’re allowed to wear velvet, like the Jews cannot wear velvet. And I actually found it inspiring, not undermining because to me, and I don’t want to get to the spoiler, the stop measure in all of history that avoids politics and political motivations from being canonized is the generational communal acceptance of the Jewish people as the number one arbiter of what is a temporal measure for 2022, for 16th century Italy. We don’t preserve things through the grand history of time, including the talmud itself without the collective acceptance at hand of the Jewish people. And anything that I’m sure there were things politically motivated through the generations but that doesn’t get passed down. Like it gets washed out over time. And I’ve seen it 1,001 times and sometimes I get stuck in something and I look around and I’m like eh, you could feel the politics like this isn’t the real thing.

Like God bless, to participate, to not participate. That’s your own choice. But like the grand history as it’s unfolding, you’re like this is not gonna be preserved in 200 years, in 50 years. Like this isn’t a part of it. And that for me is always a comfort that the ultimate arbiter, the ultimate authority was never the rabbis. It was never an individual, it was never an individual rabbi. The ultimate authority, what invests authority in anything in our canon has always been the collective hand of the Jewish people, including the tom itself. The way you conceptualize Jewish history, which like the cracks is like if you do one of those charts, you ever do that on a Shabbaton where it’s like I learned from this rebbi and this rebbi learned from that rebbi and you trace it back to like the Vilna Gaon or something like 18th century and they’re like, and the Vilna Gaon, like that traces all the way back to Moshe at Har Sinai. So like you feel this momentary respite and comfort as if like one to one my Judaism is exactly the same as what we’ve been doing since the giving of the Torah at Sinai. Which is factually not quite true.

Anonymous:

I never really thought about that so much. Yeah. But I think I pretty much believe that for most of my life that to some extent our practice today is very similar to the practice of Jews throughout history. Yaakov is Ish tam yosehv ohalim, right? Yaakov was sitting and learning in yeshiva and he knew halacha, maybe it wasn’t as developed because they didn’t have certain technological innovations or other, you know, more contemporary issues that popped up later that required. But he was sitting. He was sitting and learning and they were following halacha. There were 39 melachos on Shabbos that you weren’t allowed to do. And there were toldos those of those melachos that you weren’t allowed to do. And Yaakov Avinu was following all of them. I’m pretty sure, it’s hard for me to go back into time and remember what I actually felt. But I think I believed that to some extent that there was a large treasure of Jewish practice that goes back a really long time.

David Bashevkin:

Interesting. I agree with some of that. Not all of it. Like I think the concept of Shabbos that goes all the way back, how it was practiced, I think there’s a lot-

Anonymous:

Of oh yes, I’ve come a long way in what I

David Bashevkin:

Think Shabbos. Yeah But but that sense of like you want know that my Judaism, my individual Judaism was the same as an individual who lived 3000 years ago. I look at it now as like the arbiter has always been the preserver of the canon is not any one individual, it’s never been any one individual. It is the collective hand of the Jewish people. And it is in that collective process that we weed out over the generations through practice time. Rav Haym Soloveitchik talks about it, there are different mechanisms of how we do it. The process of drashas may be one of those mechanisms of how we ensure that what is passed down and preserved over the grand history by Knesses Yisroel, the large body of the Jewish people is as pure and free of political motivation as possible. And that I am able to believe. Can you point to me to a rabbi who was motivated or who was wrong or who was motivated by politics? Absolutely. Do I think that is weeded out over history? Covid didn’t really undermine that for me, but I definitely felt a lot of this. So let’s come back to your story. Where do you turn, like you’re starting to feel it’s not a typical crisis of faith cuz you’re still following the rules.

Anonymous:

Correct. I’m still following the rules and I’m not really struggling. My immediate response is there’s gotta be resources and answers out there that are gonna help me through this. Because I mean this is thousands of years of tradition and I am.

David Bashevkin:

It’s like a foundational question.

Anonymous:

I am by no means a scholar and intellectual like I’m a regular person. I know Jeff Bloom was on your podcast and he just said I’m just some regular guy. Yeah Jeff, with all due respect, you are not just some regular guy.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. You’re an actual regular,

Anonymous:

An actual regular guy.

David Bashevkin:

You’re not gonna to libraries, you’re not going to fancy theological conferences. Like the information you had access to isn’t exactly like buried and hidden away. Like you could get mostly, this is Amazon Prime, it’ll be by your house in two days.

Anonymous:

Oh yeah. And even to the point that I started buying things like resources online books that I thought were gonna help me with this. And then reading them and be like, wait a second, these are written by like Christians. Like these are anti like rabbinic Judaism books that are written by Christian scholars. This is exactly the opposite of what I’m trying, this is now reinforcing my questions. Could I just Google like rabbinic Judaism Second Temple Judaism, Amazon. And I get a list of books by these authors. I’m like, oh maybe these, They’re like, that’s amazing. They’re non-Jews writing about this stuff also. Like that’s great. And I start buying, I started reading this stuff. I’m like a second, my questions are legitimate.

David Bashevkin:

Did you try to turn? Meaning-

Anonymous:

Yes. So I did try to turn to people.

David Bashevkin:

What happened? Tell me about like the more classical, I have an issue with my-

Anonymous:

You go to a rabbi.

David Bashevkin:

You go to a rabbi.

Anonymous:

Okay. So one thing I will say about myself is that over the course of the last 10 to 15 years since I left YU, while I have you know, nice relationships with rabbis, I’ve lost strong relationships and connections with rabbis.

David Bashevkin:

Is that a product of this or like other stuff?

Anonymous: