Summary

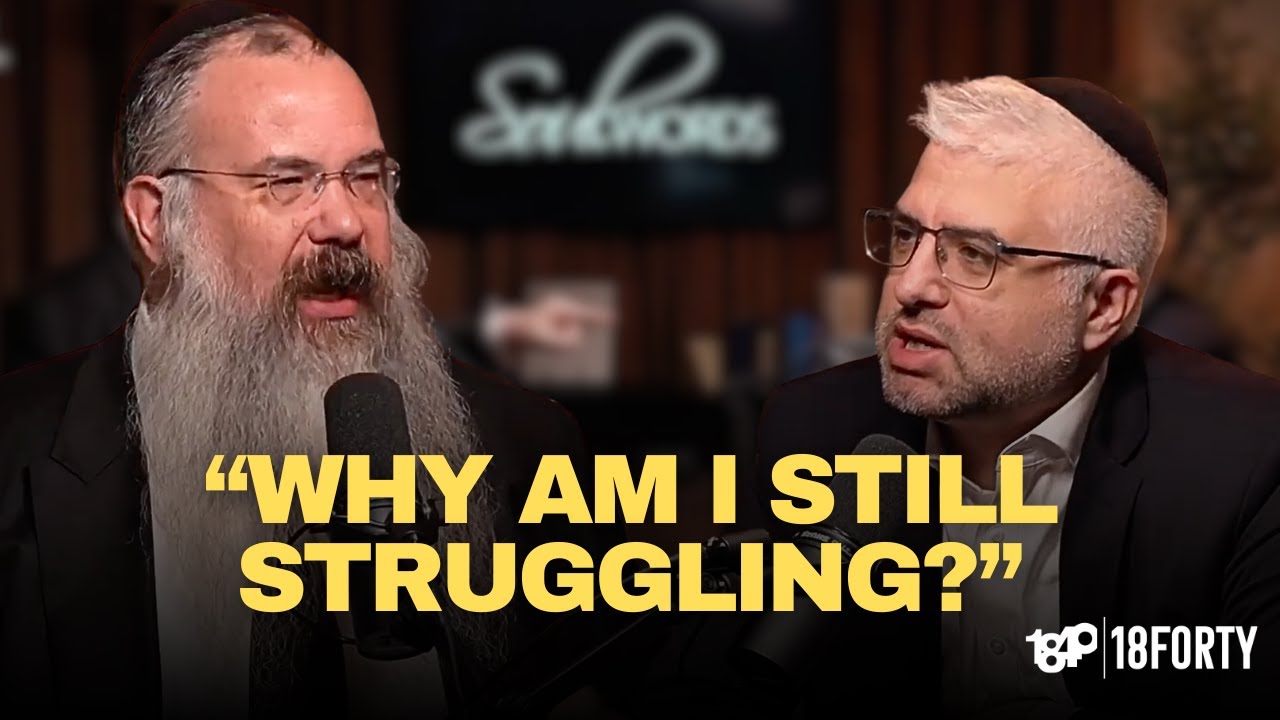

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Eli Langer and Zevy Wolman – hosts of the Kosher Money podcast – about financial literacy as it relates to Orthodox Judaism.

The cost of living in Orthodox communities is tremendous, and seems to only grow. Between tuition, simchas, and more, families in America’s top one or two percent by income struggle to get by.

- How severe is the issue of cost of living in the Orthodox community?

- What dynamics factor into this issue?

- How should we aim to solve this issue long term?

- How can financial literacy help?

Tune in to hear a conversation about financial literacy and the cost of living in the Orthodox community.

References:

Thou Shall Prosper by Rabbi Daniel Lapin

You Revealed by Rabbi Naftali Horowitz

The Index Card by Helaine Olen

Dovid Bashevkin on Kosher Money

Watch Kosher Money here.

Listen to Kosher Money here.

More info here.

Eli Langer is the CEO of Harvesting Media, and previously worked as social media producer for CNBC. Eli is the host of the Kosher Money podcast, where Eli meets with visiting experts on the financial realities and challenges of life as an observant Jew.

Zevy (Isaac) Wolman is an entrepreneur and CEO of Make it Real, a global toy company. Zevy is a founding member of Living Smarter Jewish, Relief of Baltimore, Bobbie’s Place of Baltimore, and Baltimore Business Loan fund and a board member of the Orthodox Union.

David Bashevkin:

Hello, and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast, where each month we explore a different topic, balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities, to give you new approaches to timeless, Jewish ideas. I’m your host, David Bashevkin, and this month we’re exploring wealth and finances. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big juicy Jewish ideas. So be sure to check out 18Forty.org, that’s 1-8-F-O-R-T-Y .org, where you could also find videos, articles, and recommended readings. And on the site, be sure to sign up for our weekly emails where you could get updated of all the latest content from 18Forty.

I think the first podcast that I ever listened to was a podcast about economics, business… It’s called Masters in Business by Barry Ritholtz. It’s the first podcast that I ever listened to and, honestly, it’s the one that I am most consistent about listening to every single week. But we have so many friends, especially in the Jewish podcast space, which has absolutely exploded. Really, since the pandemic, I think in 2020, is when our friends from the Meaningful People Podcast began, Jewish History Soundbites I think dates from around that time.

So many great hosts, and I’m so sorry that even listed any, because I know that I left out so many that I love and everyone who follows me online knows that my bucket list is to be on every single Jewish podcast known to humanity, and I’m on my way to it. But there was one podcast that emerged from a dear friend of mine, Jack Langer, who is one of the hosts of the Meaningful People podcast. And he’s developed, kind of, this network of different podcasts. I haven’t listened to any, that’s my admission right now.

I don’t think I’m necessarily their target audience, but they do have one podcast that I found to be really remarkable. Not just because of its content, but because of why is this podcast necessary specifically for the Jewish community? And that podcast, for those who don’t know, is called Kosher Money, and it’s hosted by Yaakov, or Jack Langer’s brother, Eli Langer, and was founded with the help of my old friend Zevy Wolman, who I go all the way back with from our yeshivah days together. And I think what fascinated me about this podcast more than anything else is, why does the Jewish community need its own podcast discussing money issues? There are so many great podcasts out there. I listened to Barry Ritholtz, there are thousands of others that talk about finance and investing, there are personal finance ones. Why would we need one specifically targeting the Jewish community?

And of course, if you’ve been paying attention or you live within the Jewish community, you likely know the answer to that question. And that is that within the Jewish community, there is a different set, in many ways, not only of expectations, but also of costs that take place within our community, that just managing your personal finances and living within the Jewish community, particularly in the United States. But this is really true throughout the world, whether you’re in Canada or in Israel. There are unique costs to the Jewish community that every community needs to be able to contend with, which is why the Kosher Money podcast, I think, was founded. Which is part of our conversation today.

They were kind enough to invite me onto their show to talk a little bit about my approach to finance. Most people who know me would not think that this is a topic that I am at all qualified or competent to be speaking about, and in many ways they are right. I am not a CPA, I don’t have a CFA. I have no fancy degrees that entitle me to really speak about personal finances, to talk about how to build wealth, how to react to wealth. My only qualifications are, first and foremost, I’m an avid reader. I read a great deal about finance, personal finance, investing. I’m deliberately a layman. I believe that a lot of our personal finance really can be boiled down to some extraordinarily simple principles.

And I discuss them on the episode, which we have linked, of course, in 18Forty. This is like an exchange program. I feel like a high school that has an exchange program. You go to some other podcast, adopt a podcast host, which took place, and hopefully we’ll be doing this with some of the other great podcasts that are out there. But there’s another thing that qualifies me and that’s the fact that I grew up and live within the Jewish community. I happen to have grown up in a fairly well to do community that’s colloquially known as the Five Towns. Can you name the Five Towns? Great question for our listeners. Everybody always leaves out one, and that usually has to with its economic status, at least when I was growing up, that’s changed a great deal. But I lived in what I call the belly of the beast of the Five Towns, and that is Lawrence.

It’s a wonderful community. It’s one that I visit at least once a month while my parents still live there. I’m absolutely in love and I’m so indebted to the shul that I grew up in. The neighbors and friends that I still have. And that world that I grew up in is still a very deep part of my life. But at the same time, I have seen changes that have taken place within the community that I grew up in that affect the community of Teaneck, that I live now, that I think affect, in many ways, the entire Jewish community. And in many ways, like the great song, we didn’t start the fire, these trends are not unique, necessarily, to the Jewish community, but parallel and reflect greater economic trends and difficulties and frustrations that people have had growing up in the modern day economy that we all live in.

So the second qualification that I have is really grounded in my own experience. I’m not a trained sociologist, but it’s something that I did mention. And there was one specific clip, one specific moment during my interview with our friends from the Kosher Money Podcast, Eli Langer and Zevy Wolman, that made the rounds a little bit online, and people in both positive and negative ways got a little bit worked up about. And I’m happy about that. So much of what we do here on 18Forty, so much of what we try to do, is to begin conversations. To keep people in the room when they are contending with all of the issues of dissonance in their Jewish lives. We’ve spoken about issues of faith and theology. We’ve spoken about sociological issues. And there’s no question that the issue of finances is an issue of tension for many. And for some people, in fact, this is an issue, as we learned on our last interview with Mark Trencher, the founder of Nishma Surveys, we know that this is an issue that for many people have caused them to leave the community. Find another place where living the living standards are a little bit different.

But I think it actually runs a little bit deeper with that. And the clip that was shared, I spoke about something that I call Gvir culture. It’s trademarked, so don’t use it, Gvir culture. So first and foremost, what does the word “gvir” mean? The word gvir is a Yiddishism that refers to somebody wealthy, and gvir culture means the culture that surrounds wealth. The culture that we as a community, in many ways, have created that surrounds wealth itself. And this is what I said when I was the guest on the Kosher Money podcast.

“All of our media need to do a better job of highlighting the average Jew and what that is like. I think we need… Again, I don’t want to like overstate it, I am terrified by Gvir culture. It was one of my early, early top fives that I wrote for Mishpacha Magazine, top five ways to tell if you’re a Gvir. And like, there’s a way that we treat them differently. There’s a way that their homes are different. There a way that we’re afraid to… They’re always right, they’re always like, “Oh, that’s such a good idea. That’s so…” And we turn them into celebrities, it’s terrible. And I think that this is very recent. This is the last 20 years that this… You have kids in their twenties who… I don’t know, I’m nervous. Can they name more gedolim or gvirim? Or even worse, have our gvirim become our gedolim? It’s very scary, and when you actually talk to a lot of these people, they’re such good, decent people. I’m not demonizing them, God forbid. But this culture of like, “Who do you want to grow up to be?” People want to grow up to be very wealthy balebatim. And I think that that’s one scary, scary thing.”

So anytime that you say something that gets passed around, people rightfully have really great questions. What exactly did I mean when I said Gvir culture? Other people were asking, hasn’t this always been an issue, this is not new? Good for you, Bashevkin, you came up with a cute name, but this is something that has been happening for quite a long time. Other people sadly thought that I was demonizing people who are wealthy. Far from it, and God forbid. I grew up in a community with a fair amount of wealth. Many of my family members, they could rightfully be called gvirim. I want to correct the record first with the last question. And this is really important, it was part of the conversation that took place, both online, on social media, people reaching out to me. Some of them not so much.

On Friday after this was posted, somebody reached out to me who I’ve never met or spoken to before. I’m not going to say his name because he was quite smug and obnoxious. And he reached out to me about this clip and said, “Don’t worry, you have nothing to fear. I live in a community with a lot of very wealthy people.” This is somebody who’s got a great job, he’s in a great industry. “And our community is half people who are extraordinarily wealthy and half the people who are not. And you have nothing to be afraid of. I want to assuage your fears.” He obviously was saying this tongue and cheek, saying that I was making a mountain out of a mole hill. His entire tone was decidedly, extraordinarily obnoxious. And dare I say, the way that he reached out to me, the way that he spoke to me, might be a symptom of the very entitlement that some people who are of means have.

And this is me calling out, not all gvirim, but this person reached out to me with a great deal of entitlement, not with a question, was extraordinarily obnoxious in the way that he interacted with me. And I would ask this person, I doubt that they listen to 18Forty, do you think the way that you reached out to me was with graciousness, with understanding, and with curiosity? I don’t mind if you argue with me, but I think anybody who reaches out with this sense of entitlement that you are wrong and essentially makes fun of me directly in the first time that they talk with me is a symptom of something that is quite corrosive. A cynicism that I really try to distance myself from.

But I do think it bears clarification. What exactly was I talking about? So, first and foremost, I was not demonizing gvirim. In fact, I think it is a responsibility that we show a measure of appreciation to the people who are able to sustain the community in which we live. I think it’s really important that we’re able to show gratitude to the people who fund, who build our yeshivas, who build our shuls, who build our social organizations, who give quite generously and are able to create the communal infrastructure, that if you know a little bit about Jewish history, what we have today, particularly in the United States of America, could arguably be said to be unprecedented in the history of the Jewish people. The type of infrastructure, the access to kosher food, the access to Jewish education. This is not the world that my parents grew up in. This is not the world that so many previous generations grew up in.

And for so many who are growing up now, they don’t appreciate the world that we live in. They don’t appreciate what kind of access and amenities that they have. And to look around and just hear complaining, or to look around and just hear demonizing of the very people who laid the foundations of the world that we have now, aside from being quite cynical, aside from being not appreciative, is patently wrong. We need to show appreciation for the people who laid the foundations for the world that we live in today. And that is something that I need to be able to state as emphatically as I’m able, and as vocally as I may have stated some criticisms about the current infrastructure that we do have now in the Jewish community. Gvir culture is not about gvirim. It’s not about wealthy people. It’s not about demonizing people who use the system that we live in today to build up means to provide to their families to live with luxury.

That is not what I am demonizing. What I am demonizing, and what the emphasis is under… And demonizing may be even a strong word. What I am critiquing, what I am concerned about, what I am worried about is the culture that we have created. The world that the next generation is growing up in and what they view as what it means to be authentic and to thrive in the Orthodox world in particular. And my concern is that we have created a structure and we have created an infrastructure and a culture that in many ways necessitates an aspirational wealth that requires young people to grow up and think to themselves, whether quietly or loudly, the only way to live a really enjoyable Jewish life is to be rich, is to be wealthy. And this is what scares me. Now, I know a lot of people don’t grow up with this. But what I think requires stating is the fact that in order to orchestrate and architecture a world in which we are not pulled into the magnetic desire of wealth just to be able to pay and to be able to live a Jewish life, it requires some measure of critique and pullback from a lot of the messages that we get sent that pull us into this mimetic desire, this communal desire, that wealth affords. Part of what I spoke about are the advertisements and the magazines that we read. Magazines that I have affiliations with that I adore, I’m not calling them out. I understand why the structure exists as such. But I am concerned that when you flip through and you look at what a kosher kitchen looks like, when you look at what a sefarim shul looks like, when you look at what the inside of a Jewish home looks like, when people close their eyes and think, “What should this look like?” They think about something that is fairly opulent and luxurious. And this can create two major problems.

First and foremost, it creates a great deal of anxiety for young people growing up. And anybody who pushes back on me on this issue is patently wrong. I just spoke to somebody in my very house who’s dealing with this. You can’t say this isn’t a problem for anybody. You may argue, because I don’t have fast facts on this. You may argue that it’s not as prevalent as I am saying, it’s not as urgent as I am saying. But to say that nobody struggles with this is patently wrong. I had a very young person in my house, a few weeks ago, who is suffering from a great deal of anxiety that is couched in the fact that the expectations of what you are able to live to create that joyful Jewish life that he believes, that I think we are all afforded, we all should be able to have access to, and is suffering because he doesn’t think he can create this for himself or his family.

This is quite scary. And I hear this from a lot of my students that there is this burden that they carry with them. They feel that they are unable to have access to the decency and to a good Jewish life without amassing a great deal of wealth. And that to me is very scary. And we have to ask ourselves, is it entirely their fault? Is it just that they don’t know how to budget correctly? Is it just that they haven’t invested in the right places? Or, the analogy that I use within this interview, the same way that individuals can buy and create a lifestyle that is beyond their means, have we done this as a community? Have we glorified a certain lifestyle as a community that is way beyond the means of the average Jew? And my question is if that is in fact the case, and you can argue that it’s not, then why are we glorifying it when we have productions in media that are targeting the common Jew?

We need to do a cheshbon hanefesh, which in English means, a consideration of our values and our soul. When we ask ourselves, are the messages we are sending out to young people healthy? Have we reconstituted what it means to be an authentic Jew when the role of luxury and wealth features so prominently in our depictions of Jewish life? The second thing that I am really scared about is the erosion of the middle. The erosion of the middle is to me in many ways the glorification that is well deserved of people who make it. They don’t live such luxurious lives, they’re not going on fancy trips and fancy programs, but they make do. In many ways, I don’t know that I grew up quite in that middle. I was probably more upper middle class.

My father was a doctor. At the end of his years, he was in private practice. But for much of growing up, we got by and we got by nicely. And the community, in a sense, what I am worried about, is the erosion of the middle. And that’s not just a media issue. That is not just what we glorify in the pages of our magazines. But the middle, the existence of the middle is eroding. Like that person who reached out to me quite obnoxiously on a Friday. He said, “In our community, we have people who live in poverty, who are learning in kollel, and they live off the largesse, the graciousness of the wealthy people who live in our community.” That is the erosion of the middle. Where on the one hand, you have people who require communal support just in order to live. And on the other hand, you have that very wealthy upper class who are able to support those people.

And what I am worried about in our stories, in our media, in the very pathways we present our children forward in their career choices, is that the middle is no longer tenable. It no longer provides a lifestyle, which in any way gets any recognition, or in any way people know how to create lives that are financially healthy and emotionally healthy within that middle. We hear a lot from people of tremendous means, and God bless them for it for all of their support. We also hear a lot from people who make tremendous financial sacrifices, who are in education, who are our teachers, who are in kollel, or whoever it is. We hear a lot from them. What I am worried about and what I am raising is the erosion of that middle.

And I wish that we had narratives and places where we spoke more openly about this middle. I’m beginning to see more of it, there were some great issues in Jewish action in Mishpacha Magazine, which we can link to, that talk more about this middle. But I am worried that the way that we talk and the way that we close our eyes and think about authenticity within our community, very often we tend to valorize and we tend to imagine the extremes while the middle becomes ever disappearing and ever less present. And it’s that middle, I believe, that requires the most support. And it’s that middle that requires the most round of applause and the most courage in order that they’re getting by. Their names aren’t on plaques and they’re not getting glorified because they’re sacrificing so much and living in poverty. But they’re the middle.

And the middle is really in important. And the middle is, what I am concerned about, is disappearing because of this overcast shadow that we have of gvir culture. I think one place that you can really see how our community’s relationship to wealth has changed is if you open up magazines. I recommend the Jewish observer from the 1980s. The way that they advertise what they’re advertising, the way that they talk about Jewish life, is simply different than what we see today. Now, of course, that is a reflection, not just of the changing role of wealth and the changing role of the Jewish community. That is a reflection of the changing role of advertising itself. And advertising is not something that the Jewish community invented, but the issue in the way that is manifest in the Jewish community is creating these two big problems. Number one, anxiety, and number two, this erosion of the middle.

And I’m worried that we are losing our ability to have diversity, not in our religious lives, but in our economic lives. To be able to have interactions and deep friendships with people who are of very different economic means than us. And to me, this is extraordinarily important, that I don’t think it’s fair, and this is something that I’m deliberately introducing before our interview with the Kosher Money Podcast. I don’t think it’s fair to just focus on personal finances. I think that there needs to be a bottom up cry out to say that the very infrastructure of communal leadership needs to change in order to address and create a pathway for this middle to be more prominent and more accessible. And we need to valorize this, that if it’s not possible to live in the middle within the Orthodox Jewish community, then dare I say that our financial obligations and the role of finances has reshaped what it even means to be Jewish in 2021.

And that to me is terrifying. That is what scares me. When our financial culture shapes the very meaning of religious affiliation, that is what scares me. And I hope that I’m wrong, I hope this is not true. But please reach out and continue this conversation because it is an important one. The person who I think deserves a great deal of applause for bringing this conversation to the fore is Rabbi Jeremy Wieder. Rabbi Wieder is a former guest on this podcast when we had him on to talk about social justice. About a month ago, he got up in the beis midrash, the central place of learning in Yeshiva University. And he decried this issue. And you can hear in his voice, this was coming from a very personal place.

And he decried both of these issues that I’m saying. He didn’t come up with the… He didn’t use the term gvir culture, because obviously that is trademarked by me, and he didn’t want to be hit with a lawsuit. But he does address the changing role of communal affiliation, and how finances play a very scary role in what it means to be Jewish in our day and age. This is what he said from the Yeshiva University beis midrash:

Rabbi Jeremy Wieder:

If you’re not cut out for a narrow slice of the white collar world, you have no place in our community. If you are struggling with any kind of mental health or similar challenges, and you weren’t cut out for certain careers, you have no future in this community. A very wise woman recently observed to me that while on Yom Kippur night, we might be sitting in shul next to avaryanim, because we do give permission, anu matirin l’hitpaleil im ha’avaryanim. We won’t be sitting next to aniyim because they’re not welcome in our community. Of course, that’s not exactly true. The person sitting next to you in shul might not be poor by any objective standard compared to the rest of America. But he or she might be drowning in our community of affluence. If one believes, as I do, that our Torah vision is emes l’amito shel Torah, and not some kind of bidey eved, then what does it say that we have constructed a community in which living in it is not a viable option for so many frum Jews?

Third, and this is what has pushed me to talk about this topic tonight, this was not my original topic. And that is the level of anxiety that exists in this room and amongst young people in our community. I imagine that all of you know exactly what I’m talking about. There are almost certainly a number of contributors to this anxiety. But I get the sense that the largest one is the herculean and seemingly insurmountable task of trying to enter a world where the economic prospects are bleak or the burden crushing. The pressure not to fall behind. The pressure to choose certain careers, which probably even leads people who would otherwise not have engaged in various kinds of cheating, or corner cutting, to do so, is enormous. Rabosai, I feel for you.

The burden that has been placed upon you by the generations that perceive you is unfair and cruel. I wish I could stand here and look you in the eye and say that we have done better, or at least we have done all that we could. And finally, and to me the most galling, is the stress created by the Yeshiva tuition issue, is a function of how we fund our schools.

David Bashevkin:

Now, we’ll come back to it, and I’m not addressing the solution that he actually shared. We’re going to talk about some of that in our later episodes. But what I am sharing is his concern. Because his concern is important. Because anybody who is struggling with this, anybody who has children, grandchildren, themselves in their own lives is struggling with this, they need to know that there are leaders who hear this, but we need a ground swelling to make sure that this is addressed for the next generation. It cannot continue on like this. And that is why I am so excited about our conversation today with the Kosher Money Podcast. Our friends, Eli and Zevy, have done incredible work about giving people, individuals, and families the tools to better understand how you can create a stable ground for your personal finances. But what I think is important to emphasize and why I am having this introduction is that I believe this is only half the story.

Half of it is on individuals and families, and half of it needs to be on communal leadership to reshape a path forward. That even if you create that stable grounding and understand the basics of personal finance, which I believe is a religious obligation, and I said this in my interview with them, and I hope that you’ll check it out. But that can only be half the story. There needs to be leadership that helps people understand a path forward for how the very shape of our community needs to be accommodating and accessible. That we don’t lose this middle. We don’t lose young people who are anxious about how they’re going to chart their financial path forward to create a Jewish community that is accessible and joyful, no matter your economic identity. So it is with great excitement that we discuss half the story with our friends, Eli Langer and Zevy Wolman, of the Kosher Money Podcast.

Why exactly did you begin a podcast called Kosher Money? Isn’t personal finance an issue that is dealt with in the non-Jewish community? Why did we need a podcast specifically for the Jewish community and the way that we handle money?

Eli Langer:

So for starters, personal finance and what we’re trying to accomplish here isn’t necessarily an Orthodox Jewish issue. You have Dave Ramsey, and he does phenomenal work, and there are many rabid Orthodox Jewish fans of his. But there are issues that pertain to our community that are very, very specific to our community, that will not be discussed in a Dave Ramsey episode. My brother Yaakov, who’s behind the Living L’chaim Network, he approached me, I would say about eight months ago, connected me with Zevy, and we realized we have to do something to discuss personal finance, help people through this. There’s never been a better time to disseminate media. Let’s do this. And I would say, we’re probably about six months in, with minimal advertising, and we have over 175,000 listens so far. Zevy, what do you think? Oh, I’m the host now David.

Zevy Wolman:

Yeah, I’m used to being asked questions by Eli, so this is much more my comfort zone. No, I agree with what Eli said. I think the goal was to start a conversation. And we’ve done that. I mean, what’s funny is that people always are sending us these voice notes and they start with an apology. Like, “I really didn’t agree with what that guy said.” Like, “I’m sorry. That was just like… We don’t do it that way or that’s not right.” And what’s funny is, Eli and Yaakov and I always say, like we have this sort of running chat together where we get all this feedback, and we’re like, “No, that’s the point.” We want people disagreeing. We want people talking about it. And to Eli’s point, there’s a real lack of education.

And I think, probably we’ll get to that a little bit later in the podcast. But there’s a significant lack of education for some reason about financial literacy, which is something that affects every single one of us, irrespective of what we choose to do with our lives, with our careers, whether we’re in kley kodesh, or in the working world. And for whatever reason, we’re not being prepared. And, like Eli said, there’s a tremendous amount of frum specific issues. And the goal was to start a conversation, even be a little controversial, Eli’s really good at being controversial. And yeah, we’re trying to start a conversation and that’s baruch Hashem what we’ve been able to do.

David Bashevkin:

So, I’m glad you raised that. And I actually want to begin with something maybe fairly controversial. And that is, I have mixed feelings about the very approach of your podcast. It feels like you are equipping people with a plastic spoon to fight a dragon. In that, the major problem, particularly in the Orthodox world, people who want to raise their kids and give them a Jewish education, is the cost of Jewish education. It overshadows every other issue by leaps and bounds. And my question is, you talk about personal finance, but to me, the real solution needs to be institutional. Putting pressure on institutions and saying, “The life that you are asking us to lead is no longer affordable. This is not sustainable.”

How do you reconcile the fact that you’re giving people budgeting, and take certain extravagances. Maybe don’t spend so much money on Shabbos meat, and buy chicken instead. Make sure you get a good mortgage rate. These are all nice things. But my mortgage, and I’ll tell you, I pay $3,000 a month including taxes. But if I have three kids in Yeshiva and I’m paying full tuition, that could be many orders of magnitude greater than $3,000. So, what role does personal strategy play when the problem ultimately stems from institutional factors?

Zevy Wolman:

It’s a great question. And you know, there isn’t a silver bullet here. But I would say two things. The first thing that I would say, and it really depends on who’s listening to this, because the cost of Jewish education varies from community to community. And not just does it vary from community to community geographically, but it varies from community to community hashkafically. So the cost of Jewish education in Lakewood doesn’t resemble the cost of Jewish education up the road two exits up the Garden State Parkway, in a more modern Orthodox school. And so, what’s extremely important that people have to understand, is that both from an in town and out of town perspective, the cost of Jewish education is dramatically different. And from a communal perspective, the issues that are facing in some ways the more Yeshivish community are not the same issues facing the modern Orthodox community. Yeshivish community tuition in Lakewood ranges anywhere from five to eight thousand dollars. In Flatbush, it’s eight to eleven thousand dollars a year.

That’s not cheap, but it’s also not the cost of education in Halb or HAFTR at 15 to 25 to 30 to 35 thousand dollars a year. And so it’s extremely important to, first of all, be nuanced the approach to understanding the challenge for each respective community. And then the second thing that I would say to you is, listen, you’re right, a hundred percent. Let’s take it at its most extreme. Let’s say that we’re talking about a community where, a modern Orthodox institution, where families with five, four kids, who are making less than 300, 350 thousand dollars qualify for a tuition reduction.

Right, that means we’re basically saying that if you make less, this is our big thing, right? You could be making in the top one and a half to two percent of income earners in America, and in our community, you’re considered, quote unquote, needing of financial assistance from other people. Which is essentially, in some ways, what we’re saying to families. And for those schools, even if you take the most extreme cases where the schools are the most expensive, at the end of the day, that’s not a reason not to equip families, A, to plan for it. Because like Rabbi Howard always says, a lot of the expenses in frum life are not surprise parties.

Weddings are not surprise parties. Bar mitzvahs are not surprise parties. Baruch Hashem we know that a boy is going to be born, 13 years later these expenses are real. So, to help people put in perspective the expenses that they can control, whether it’s the cost of living and the cost of where they live, meaning housing, the cost of making simchas, and helping them plan for it, helping them invest for it, helping them understand how to budget for it and not go into debt that they don’t need to go into, I don’t think it’s fair to say that by virtue of the fact that we have an infrastructural cost that is absolutely overwhelming, therefore, we throw in the towel and we don’t help people with the secondary tertiary costs that are also massive contributors to this issue. I’m sure, probably a lot of your listeners listen to Rabbi Jeremy Wieder’s –

David Bashevkin:

Sure I shared it publicly. And we will be sharing it, clips from it, once again on this show.

Zevy Wolman:

Right, and I think what he said was, I think he acknowledged that he was trying to do is galvanize an entire generation of youth to bang on the doors and scream for change. But I’ll be totally honest with you. I don’t know how quickly change comes. I mean, we talk about, the OU and the Agudht talk about lobbying government for funding and all of that. And that’s fine, very important, great, necessary. And even Rabbi Wieder admitted, probably not going to make a dent in the overall cost of tuition. And so, what he’s talking about is we have to completely rethink the way we approach tuition and we have to bang on the gates and we have to explain that communities have to be funding it. It’s not the parents. I don’t know when that’s going to happen, I don’t know. Is that something which is going to make a meaningful change overnight? I don’t know. But in the meantime, does that mean that we don’t approach the other major issues that are facing families? I don’t think that’s the right approach either.

David Bashevkin:

I want to come back to this question. I want to give a question to Eli, and you could weigh on this as well, what Zevy spoke about. But I want to ask you in terms of the personal finance. So you’ve been running this show for a few months already, and I’m curious, so help me out. We can’t necessarily change these major institutional factors. So what have you found to be the most common mistakes that you’ve been making, that you’ve seen other people making, that have resonated the most, “Oh, I didn’t know I shouldn’t be doing that?” What are the most common mistakes you have been seeing people make with their personal finances?

Eli Langer:

I think one answer, budgeting. People are running around without heads. They’re not thinking about what they’re spending. They’re not taking into account how much they need to have for retirement. They’re not thinking about what they need to have for a rainy day fund. They’re not thinking about how much they need to allocate towards life insurance. They’re not thinking about, “Hey, maybe if I cut back on groceries, I can meaningfully save 600 bucks a month.” And you talk about plastic spoons. I would say it’s more like a ladle. Like, it’s one of those hard wooden spoons where, you’re right, it’s not –

David Bashevkin:

It can be used as a weapon.

Eli Langer:

Right. But if we give people enough ladles, I think we can actually make some sort of indentation into this issue. So, we’ve already had 15 episodes, and we’ve covered two of them on budgeting, right? There are people that are getting credit card bills, paying them off. That’s fine. Ignoring all the debt within the community. People do not have a good sense as to what they’re spending. We had a budgeter on, she volunteers, that’s what she does. She helps couples with their finances. After our episode, Zevy, how many couples do you think have visited her since she joined?

Zevy Wolman:

It’s unbelievable, she’s booked months out now.

David Bashevkin:

And who is it? Could you say her name? I mean, she was a public guest, why not?

Zevy Wolman:

Yeah, it was Stacey Zrihen, and she works in Achiezer. And what was fascinating about it is that before our podcast aired, she was bored. She did not have a lot of people that were approaching her. And now she’s overwhelmed months out. And to Eli’s point, I think it’s a really good point.

Eli Langer:

I visited her with my wife, and we walked away with tangible things in which we can save, without exaggeration, tens of thousands of dollars a year. She looks at my health insurance, she says, “You know, you’re spending 30% more than the average family that comes in that lives in your neighborhood?” I go, “No.” She’s like, “You know, you could be saving $1,500 if you invested in smart water sprinklers.” Now again, $1,500 at the end of the day may or may not be that impactful. But when you start adding up these plastic spoons, you’re dealing with potentially tens of thousands of dollars a year that I wouldn’t have had had I just been a bit smarter, had I been educated on how to spend money. I find that people in their twenties, they get married. I hear from their fathers and their mothers that they don’t even know how to open up a bank account.

Everything’s been spoonfed to them. They don’t know how to write a check. They don’t know the difference between a credit and a debit card. You know, these are real issues that people are learning on the fly. They’re getting into their early thirties. Maybe they’ve been managing, but no one ever taught them that said, “Hey, not only do you need life insurance, you need adequate life insurance.” You know, you can’t have a $500,000 policy for three kids. If God forbid something was to happen to you, your family would be able to survive for two, three years before there’s a GoFundMe set up. That’s not okay.

David Bashevkin:

You spoke about being fed by a spoon. And I want to hear both of you weigh in on this, you could choose who to go first. I began with the institutional factors, and we know that the cost of Jewish education is more. Help me dig deeper in how we diagnose, how we got to this problem, and let’s both agree that there’s a problem that your show, that people is happening on Shabbos tables across the country, is trying to solve. And I want to frame it this way because I almost want to frame it in theological terms. We so often, there are so many beautiful values that are cultivated in the Jewish community. The values of education, the values of family, the values of Shabbos, of davening, of Torah. There’s so many beautiful things in the Jewish community. Why are these values not translating into a healthy relationship with material wealth? A healthy relationship with luxury?

Why is it that when you turn around and you go to almost less wealthy communities, and very often they’re not as religious in many ways. They’re out of town, they don’t have the same infrastructure. Why is it that when you go to the belly of the beast, I grew up in the five towns and I love the five towns, it’s brimming with Torah, it’s brimming with religious values. But I get worried that it’s very often expressed through a very unhealthy relationship with luxury and material wealth. How do you diagnose this relationship? Why is it that in many communities, not all, and I’m not condemning material wealth and luxury. But to help me diagnose how we got to this problem? How is it that our relationship with luxury has become so skewed and so unhealthy? And this has taken place in my lifetime. When I was growing up, I knew that some people had maybe nicer homes. I didn’t know who was wealthy. I didn’t know that there was a big difference. I didn’t know I was considered wealthy until I was in Ner Yisroel and started getting mentioned for shidduch dates with the daughters of roshei yeshiva. Then I said, “I must be wealthy. What’s going on here?” I had no idea. How do you diagnose, beyond the tuition factor, how did this problem begin?

Zevy Wolman:

Wow, okay. I have a theory on this. The first thing I want to say is what you’re discussing now is something completely separate from what we’ve been discussing up until now. Up until now, we’ve discussed infrastructural costs. Basically having nothing to do with what type of fancy car you drive, or anything like that, you live in a frum community, housing costs are more expensive, kosher food is more expensive, tuition is more expensive. It just costs more period, having nothing to do with ostentatious consumption.

David Bashevkin:

Correct.

Zevy Wolman:

So, that’s one issue. That was what we’ve been discussing more or less, up until now. You’re talking about a separate issue, which we really got into a little bit on our podcast with Naftali Horowitz, which is conspicuous consumption. And we got into a lot of trouble with this, because Rabbi Howard had one approach, and Naftali had another approach, and we’ve been kind of fighting the battle since then. But you’re asking –

David Bashevkin:

Can you unpack that? What were the two different approaches?

Zevy Wolman:

The approaches were how to deal with conspicuous consumption. Both of them agreed that it’s a major issue. Both of them, I think you expressed it beautifully in your question, which is, where is the disconnect? What in the world happened, and how do we approach it? And Naftali’s approach, which I think is the approach of many of the rabbanim that I’ve heard. I think at the Agudah Convention recently, Rabbi Elefant expressed it in very, very explicit terms as well, which is that this is an absolute tragedy for our community. It’s a disaster. It’s leading us down a path that we can’t come back from. I don’t remember exactly what the expression was, but it was like some like very strong approach. And Naftali has the same approach. And he literally goes from community to community. Gets up in the sefardic community, and the chassidish community, and he gets up and screams.

And Rabbi Howard’s approach is very different, which is that you cannot tell wealthy people, you cannot get up there and scream at them for what they’re doing. You cannot tell them how to spend and what they should be spending on. You encourage them and promote healthy values, encourage them to use it as an opportunity, to use their spending as an opportunity to make a difference, and to not create this culture of aspiration. But you can’t tell people what to do because it’s just plain ineffective. And I think we got a lot of feedback on that and even gave both of them a chance to respond to each other. And I think they very respectfully agree to disagree. That it’s a problem, but the approach can’t be to yell and scream. But to answer your question, as a diagnosis of how we got there. I’m going to say something that might be slightly controversial, but I don’t know if you’re familiar with the prosperity gospel in the Christian approach?

David Bashevkin:

Tell us.

Zevy Wolman:

The prosperity gospel, basically, it’s a lot of these preachers that you see on TV with beautiful airplanes and just absolutely extravagant lifestyle. And basically what their mehalech is, and they’ll say it specifically, is that when you talk about money and you are not afraid to talk about money, you’re not afraid to spend, you’re not afraid to conspicuously consume, it encourages people to give and to view money as a way to God, and to not be ashamed of money, and to not feel like you need to live a very impoverished lifestyle. And I heard it from one Rav here in Baltimore, who said it explicitly, “That I encourage my balabatim to spend on themself and to spend conspicuously on themself, because by doing that, they will then, in turn, spend conspicuously on the shul and in giving to Yeshivas and in their giving in general.

Eli Langer:

David’s shaking his head by the way, Zevy. I’m watching on the screen.

David Bashevkin:

No, no, no I’m listening. I’m listening.

Zevy Wolman:

That’s not a, “David is shaking a no” head, that’s a, “David imbibing and trying to – ”

Eli Langer:

Pondering?

Zevy Wolman:

Pondering. So, he said we have to encourage conspicuous consumption, because that’s how you get $2 million charity campaigns in 24 hours, and 10 million dollar dinners and things like that. Because if you don’t, now there’s a massive corollary. I said, “Wait a second. But how about the corollary effect to that?” A, you’re encouraging people to spend who don’t have. And B, it’s causing like a tremendous amount of chalishas hadas –

David Bashevkin:

What does chalishas hadas mean? I’ve never heard that term.

Zevy Wolman:

Chalishas hadas, I don’t know. It’s one of those terms that doesn’t have a fantastic English translation. It’s like geshikt. No. Chalishas hadas is people feel –

David Bashevkin:

People feel way down, people feel burdened.

Zevy Wolman:

Yeah. It’s like a FOMO. Like a fear of missing out. Like if I’m not participating in that lifestyle, I’m somehow less than.

David Bashevkin:

Yes.

Eli Langer:

Keeping up with the cones, right?

Zevy Wolman:

Yeah, like feeling the need to keep up, and if not, that it’s somehow how we express ourselves and how we express ourselves, our worth is through money. And it’s a great question. I don’t know if that’s how we got here, but that’s certainly what I heard from one Rav who encourages that very strongly. And said, “Yeah, there’s going to be like a corollary effect to that, but it is what it is.”

David Bashevkin:

Eli, do you have thoughts on this?

Eli Langer:

Honestly, haven’t thought about it much, nor do I care. I know we’re here. This is something that we’re grappling with. We need to find a way out. And if we don’t have this dialogue, we’re in trouble, right? There was a Nishma study, 97% of Orthodox Jews think personal finance is the biggest burden of being an Orthodox Jew. And that’s not okay. Now, if we go back years and years and try to figure out why we got here, maybe that can be part of this solution. But I think the very fact that we’re having this conversation is a step in the right direction. I don’t know what took place in the nineties and the O’s. And even before that, dating back to 1840. Great podcast by the way. We’re here, we’re here. This is not something that’s going away.

What got us here? I don’t know. But I know that 15 episodes in, the amount of people that have met with a budgeter, that have gotten more life insurance, that have started making progress when they feel burdened is huge. And to Zevy’s point, there is also a lot of debt within this community. We don’t want to give off the fact that people listening should feel that chalishas hadas, that burden, because, “Hey, so and so is driving such a vehicle. How did he afford a Range Rover?” We had Naftali Horowitz on an episode, and he said –

David Bashevkin:

And who’s Naftali Horowitz?

Eli Langer:

Naftali Horowitz works for JP Morgan Chase. They’re a branch within that company. He’s an investment advisor, I believe. And he had a great story. He said he was heading to the city and he was being driven by a friend of a friend. And when they got to the city, parking was limited, and they had to park in a lot. And the attendance said the lot costs $50 for the hour. And the fellow driving the Range Rover turned to Rav Naftali Horowitz and said, “Can you lend me $50?” He says, “Yeah, sure, no problem. But you’re driving a Range Rover. Is it a cash issue? You don’t have a credit card?” He goes, “No, I have so much debt. I can’t just keep piling on.” And he said, “So tell me, sir. Why are you driving a range Rover?” And he said, “Because everyone else is.” And that’s a problem.

Zevy Wolman:

Can I say another Range Rover story while we’re on Range Rovers?

David Bashevkin:

Please, more Range Rover stories. I –

Zevy Wolman:

Yeah, more Range Rover stories. So –

David Bashevkin:

I have a Honda Pilot. I’m going to have to go out and see if I could –

Zevy Wolman:

Yeah, we’ll get to you later, David. Because I have a lot to say about you and your relationship to money that Klal Yisrael has discovered over the last 48 hours. But we’ll get back to that in a minute. This was a text storm that came into the Living Smarter Jewish chat, WhatsApp yesterday. I have someone who works for me that makes a $130,000. His lease was up, he told me he wants a Range Rover. I said, “It’s none of my business, but I think you should reconsider getting that for $1,500 a month.” He’s not very wealthy. In the old days a Range Rover was status, elite. Now you’re just trying to be like everybody else. You’re not even getting the eliteness of it, and you’re going to be broke, so why bother? He said to me, “How can I not drive it? I’m going to feel like such a loser because everybody else has one.” By the way, he’s a nice, normal, smart guy. It’s just such a culture of hedonism and insecurity. Sorry for the long-winded message.

David Bashevkin:

I’m beginning to feel like a loser myself with my Honda Pilot. I never did until now, but I’m beginning to question that. I want to come back to the effects of conspicuous consumption and how it affects the leadership within our community. Before we do, you just mentioned Living Smarter Jewish. What exactly is that? I’ve never heard of that before.

Zevy Wolman:

Okay, so Living Smarter Jewish is an organization that we started in partnership with the OU a few months ago. And the goal is to provide a complete 360 degree approach to personal finance issues in the Jewish people and give people somewhere to turn for all of it. So it’s really three pillars, it’s inspiration, education, and then one-on-one assistance. So we try to work through Kosher Money. We were partnering with Kosher Money to try to inspire people to think and to start conversations, articles in Mishpacha and Jewish action, things like that.

On the education side, we’ve developed a curriculum that we’re offering free of charge, two curricula actually. One for a beginner curriculum and a more sophisticated financial literacy curriculum for high schools that’s available free of charge. And then we have multiple on our website of various different verticals of education, trying to give people the education that they need. And then working with individuals, we are working one-on-one. We’ve recruited 30 newlywed coaches to work one-on-one with newlyweds to help them get set up with a budget, help them set up their bank accounts and invest. Then we have 90 coaches that are available to work one-on-one with families across the country to help them develop a budget.

David Bashevkin:

Wow, I would love to some of these materials that we could give out to some of our listeners. That sounds absolutely fascinating. I want to kind of have you weigh in on one of the effects in my mind of how, and this is conspicuous consumption materialism. How it’s shaping the very contours of what it means to affiliate within our community. And I am concerned that this is having a very corrosive effect on the way we even look at rabbinic leadership, and that it is actually uprooting and really evolving the very nature of rabbinic authority. Because if you grow up in a wealthy home, the person who is coming to you, the person who is what you see of what brings rabbinic leadership into people’s homes is almost always wealth. And I have this concern when it comes to outreach shabbatons. And you run a shabbaton and you bring people who are becoming more observant, more affiliated with the Orthodox community, and you have a shabbaton, and you bring them to a Friday night activity. And you always bring them to the wealthiest, most extravagant homes.

And here is the circle that I would like to try to square with you today. Everybody will immediately say that this is necessary. You have to bread your butter. You have to figure out a way to keep our institutions going forward. As you said, they will give extravagantly if we allow them to spend extravagantly. But aren’t you concerned, and is there any way to address that when you grow up in this world now, the center of power in the community, in many ways, is wealth. In ways that are more conspicuous and noticeable than it was when I was growing up. I didn’t know, when I was even in high school, who the big movers and shakers of the community were. There wasn’t this culture, as I mentioned when I was a guest on your show, this gvir culture of becoming an askan, a communal leader, and the prestige associated with it, the specious prestige associated with it. Is there any way that we can fund our communal givings without overly glorifying all of the culture related to wealth?

Eli Langer:

So for starters, I’ve learned in this podcast, over the last season and a half, that back in the day, yeshivas were not funded by individual families. It was the community as a whole that got together to help fund the establishment. Nowadays, it’s the responsibility of the families to fund their school’s tuition education. We’ve moved away from that entirely. Now it’s, your kids are out of school, you’re no longer obliged to give any financial support. So, I think things have changed in which we are looking at an entirely new scenario. We’re not relying on the community as a whole anymore. So where are we turning? We need to fund. If a large school here in the Five Towns has a $42 million budget, and tuition only raises $35 million, where’s that other 7 million coming from? It’s coming from the gvirim. It’s coming from people that appreciate and understand what the yeshivas are trying to do and have the resources to fund that.

So you talk about squaring a circle to a square, to a plastic spoon, to a ladel, this is the reality, right. We have to fund that gap. And if you’re not going to rely and lean and give sort of that covet to the gvirim, where else is it coming from?

David Bashevkin:

Zevy, do you have thoughts on this? Because I appreciate this, but to me it sounds like, on the individual level, it sounds a little bit like the person who brought the Range Rover and can’t afford it, and it sounds like we’ve made the same mistake on a communal level. Where we insisted on building incredible institutions that are absolutely wonderful. But have we built more than we can sustain? And now in order to sustain it, we are sacrificing so much in the very character of what it means to affiliate within our community.

Zevy Wolman:

It’s such a good question. The first thing I want to just point out is that you asked me to translate chalishas hadas, but I don’t get to ask you to translate specious consumption. But we’ll leave that for another time. I think it’s a really good point. And I’ll be honest with you. So, there’s two things. First there’s a famous Rabbeinu Yonah which talks about that a person’s self worth is ish lefi mehalelo. And Rabbeinu Yonah says that ish lefi mehalelo means that a person is judged by who he praises. In other words, that when a person after 120 years is going to go up, the Ribono shel Olam is going to ask him, “Who are the people that you look up to, and who are the people that you talked about and that you glorified?”

David Bashevkin:

Meaning the simple meaning of that verse in Proverbs is that a person is measured based on their praise. Which you would think it’s the accolades that other people give to them. And he reinterprets it and says, “No, it’s not the accolades that others give them. A person is measured based on what that person praises.”

Zevy Wolman:

Exactly.

David Bashevkin:

What do you hold as valuable.

Zevy Wolman:

Exactly, but thank you for that. And so from my perspective, I think the first point is, when we were growing up, okay, I know… I agree with you, by the way. I also didn’t notice everybody’s cars, and this whole culture, which I think is probably fueled somewhat by social media. It wasn’t as noticeable. With that being said, I don’t think that it didn’t exist in the sense that it wasn’t the same people that were funding institutions. I grew up in Toronto, right? Toronto Baruch Hashem is blessed with an enormous amount of wealth and wealthy families and money that’s concentrated in the hands of a few who have been single handedly funding the institutions there for years. It was never dependent on tuition. It was never dependent on the entire community chipping in a couple thousand dollars. It was funded by families.

And it’s a beautiful thing. And so I don’t think it wasn’t happening in the eighties, nineties and O’s. I think now, it’s just become a culture where everybody’s trying to outdo everybody else in terms of showing kavod and showing honor. And that puts a huge pressure on the quotient that we were discussing before of, what are we praising and what are we showing our kids that we’re praising? But I got to be honest with you, this notion that every family in the community is going to kick in a few thousand dollars and it’s going to solve the problem, I mean, the elephant in the room is that the problem is getting worse and not better because of the teacher crisis.

And I’m sorry, it’s just, at the end of the day, we’re looking at a problem with, by virtue of the fact that most communities are struggling to recruit young people to be teachers, there’s a lot of reasons for that, but the reality is that the only way that that’s going to change is by dramatically increasing salaries. And that’s just going to create even more of a need for more money. And so this idea that our school, no, the budget’s $10 million and we need to break it up among 4,000 families so everybody kicks in, I just don’t think it’s realistic. And so I think we have to change our perspective on it and not pretend that it’s all going to change overnight because I don’t think it is.

David Bashevkin:

A recurring theme that I have been kind of asking in my questions just to frame it has been that my frustration is that the individual reflection that you on your show ask of individuals and families to budget and to think about what they really need and what they really to do is not being reflected on the communal level in how we budget, what we build, and what therefore creates the need and the wants on that larger level. So I want to ask almost a rapid fire question. On the communal level, what is something of conspicuous consumption? We’ve railed on Range Rovers. Tell me something on the communal level conspicuous consumption that you cringe and you wish was taken off of our communal budget.

Eli Langer:

Clothing. Kids’ clothing in particular. The kid is growing out of it in about six months and then you’re right back to where you started. I think we need to, and my wife’s family does a really good job, giving clothing to other siblings and they have baskets based on the ages. I think people spending on clothing has gotten out of hand and that adds up quickly. So, if we were a little bit more mindful and say, “Hey, I don’t need to spend $120 on a Yom Tov dress when my sister has a Yom Tov of dress.” And I can’t help but think that’s like a plastic spoon, again, floating over your head.

Because nothing that we’re suggesting, and this has been a theme, nothing we suggest will magically change the financial scenarios for anyone. The only solution that I found that can meaningfully change someone’s financial wellbeing is moving so-called out of town. Because your finances completely change. Your cost of tuition lowers, the cost of food. Everything gets lower to the point where, in post-COVID world, you’re able to make same amount of money, you’re working remotely, but yet your budget is 60% less than what it normally was. Zevy, what do you think?

David Bashevkin:

What do you weigh in on? And I want to just make sure in the question, I really want it to be something on the communal budget. Something that you see advertised publicly that’s coming from institutions, ideally. Which is why I’m only going to give partial credit to Eli. We railed on Range Rovers, we could talk about what you’re buying, the luxuries for Shabbas. Is there anything on the communal budget that you think should be to taken a second look at, or that you at least cringe when you see it? I’m going to answer this question myself, if you –

Eli Langer:

And I do want another chance.

David Bashevkin:

You’ll get one.

Zevy Wolman:

I’m uncomfortable criticizing anything sort of communally. I don’t feel like I’m roi for that, I’m worthy for that. What I would comment just maybe to take it somewhere between Eli and what you’re saying is simchas, because I think the amount of money that’s spent on simchas is just, it’s unbelievable. And people have said it to us again and again, hundreds and hundreds of thousands of dollars are spent. And I think one of the, not to rehash something which has been said a lot, but over COVID people found out that you could actually make a wedding with not that many people. We made a bar mitzvah with fewer people, whatever it was. And Baruch Hashem, my son is still bar mitzvah. I don’t know if he’s, whatever. But he’s still bar mitzvah, it still worked, and yeah.

Eli Langer:

And it was an even nicer simcha. People felt that the more intimate setting with 20 people in their backyard was nicer than any wedding they could have spent $300,000.

David Bashevkin:

Well, Eli, did you get invited to Zevy son’s bar mitzvah? Because I did not receive an invitation.

Zevy Wolman:

No, no.

Eli Langer:

No, he said COVID threw the whole mail into loops.

David Bashevkin:

Oh, yes.

Eli Langer:

It was a supply chain issue. But to that point, I would pose a question back to you, David, in the sense that when you talk about communal issues, why is tuition in one neighborhood 25 to 35 thousand dollars a year per student in one school, but yet you look at another school and tuition’s somewhere between 5 and 10 thousand dollars? Some communities have figured out that, hey, maybe not having a ballet class is the most integral piece to my kids’ education. Or maybe not having the best Phys Ed teacher or science teacher that five kids are going to into that class, and everyone has to share the burden, thereby increasing the amount of the annual tuition. Some schools, like we see in Lakewood, and I’m not comparing the education. So I’m just comparing the communal pressures and the asks from the parents are a whole lot higher in one area versus others.

David Bashevkin:

Number one, I’m doing the questions around here, Eli. So, check yourself. That’s number one.

Eli Langer:

I feel like Conan on David Letterman. I have my own podcast. I always thought when they sat there, it was always weird to hear Conan answering the questions, not that I’m comparing myself to him. But you do have that David Letterman look, the style, you have all the books behind you –

David Bashevkin:

Don’t get me started with late night television. We’re going to go way off topic. I want to give briefly my answer. It’s fairly controversial, you may absolutely hate it. But I just want to go on the record. I do not like the advertisements and the push, and specifically this, for trips to Europe to visit kivrei tzadikim, the grave sites of holy people. I think it is an extravagant expense and luxury that have become luxury events for people and experiences that I don’t think our community should be putting on a pedestal, and mixes together in ways that make me deeply uncomfortable the authentic religious experience and conspicuous consumption. If you can afford it, go away, do it quietly. But programs that have private chefs outside of the old village of Rav Elimelech of Lizhensk make me deeply uncomfortable.

I know I’m not going to win friends by saying that. But that is a trend that I did not see when I was growing up. It is more and more common to see it advertised, to see these big trips going on. And it is not something that makes me all that comfortable. And to come back to your question, I absolutely agree that there are differences in communities. And maybe this can get to a point that we were talking about, which is, you made a curriculum to teach financial education in yeshivas. And I assume that you are targeting a more right wing community. That is my guess, that the bulk of your listeners are probably a little bit to the right than maybe the listeners of 18Forty, or certainly of kind of a left wing or centrist Modern Orthodox community. Though much of what you say is relevant to everyone.

My question is, did you get any sort of pushback from the institutions? And I know Zevy is so careful not to criticize institutions, which is some of my criticism that I am sharing with you today. But did you get any pushback about integrating these points inside of our yeshivas, inside of our seminaries? Or do you think because of the need for a more serious education that there is a turn in the community in the way that the yeshiva system is looking at financial education? Has that changed given the magnitude of the problem?

Zevy Wolman:

In one word, yes. I think you really, sheylas chacham chatzi teshuva. The question of a wise man is half of the answer. And I think you really did, you really did it justice. I’ve been in this issue for about 12 or 13 years, it’s been a passion, and I’ve been involved in different organizations. And it used to be much harder. It used to be much, much harder. What’s interesting is that a lot of the yeshivas on the right wing, many yeshivas are doing away with all secular studies completely after age 13. I believe somebody mentioned that in a certain community, there’s only three out of the 50 schools that are teaching secular studies after age 13, the 50 high schools. But even with that being said, I got a call from a principal in Borough Park. And he said to me, “I have one hour a day of secular studies that I’m allotted to teach it.”

He’s like, “I don’t know what,”… And this is a college graduate. So I don’t know, probably modern Orthodox, maybe not frum, I don’t even know. And he said, “Honestly, I don’t even know what I can do with an hour. I’m not going to accomplish the New York state curriculum or the Regents.” He’s like, “I’ll tell you what.” He’s like, “You can have my hour.” He’s like, if I teach nothing else, at the very least, let them be financially literate. Let them understand all of the concepts that are in the curriculum. And so, I think you are a hundred percent right, the wheel is turning and people are appreciating the hole that not having education leaves in a young couple’s life.

David Bashevkin:

A part of that is heartbreaking, obviously, because I do believe that we are not setting up the next generation for success in the way that we raise them. Which really leads me to kind of the final leg of this conversation. And I want to talk to both of you about your own personal relationship with money, and who gave you your financial education. I kind of want to begin, I know you’ve been speaking a lot, Zevy, but I want to begin with you. And I hope you’re comfortable with me bringing this up. Your father passed away when we were in yeshiva, which required you to go to work at a age when I don’t think that you expected to begin working. It hastened the maturity, I think a lot of the people who lose parents, it hastens a sense of maturity and responsibility.

Given your unique set of circumstances, when you look at people who were not forced, obviously because of there, there’s a sadness, there’s a trauma, you had a father. We drove through the night through Canada. It’s one of my, dare I say, fondest, most powerful memories from yeshiva, driving through the night to pay a shiva call to you and your family. But when you look at other families who are not forced into those circumstances, what do you want to tell them about the difficulty that your specific set of circumstances forced you into? Would you say, you know what, obviously nobody wants to lose a parent at a young age. But it must have taught you something about how responsibility is integrated into somebody’s personal life in ways that I think we are missing, in many ways, particularly in the Orthodox community. How we transition into the workplace. How we transition into starting our own budget, making our own money. What did your experiences teach you about how we should be educating our children about money?

Zevy Wolman:

Wow, okay, just for the record for those listening, I had no heads up about that question. So the first thing is I do want to say that was probably the most meaningful, the way that Ner Yisroel treated me, both in my friends who came to be menachem avel, and the way the yeshiva treated me in allowing me to actually… I’m an only child. So just to provide a little bit more context, I’m an only child. And there was nobody else in the business. My father was, more or less, a sole practitioner who had a relatively small business. And the yeshiva allowed me to have internet, which back in those days meant you would plug in a flip phone to an enormous laptop to get some form of dial up. And they allowed me to have that in the dormitory and to work bein hasdarim. Which not only kept me in the Yeshiva, but even when I was learning in Kolel I was still working.

That’s just a little bit of context and a tremendous amount of hakaras hatov to you and to everybody else who was there for me at the time. With that being said, I did a lot of dumb things when I took over my father’s business because I wasn’t ready for it. My father got sick and died six months later. So I did not have a lot of prep time. I hadn’t started college yet. So I made a lot of really stupid mistakes. And I’m not like ashamed to admit that, I think David you’re my inspiration in that. Your approach to personal transparency, I mean, in general I’m much more of a private person, and this whole kosher money experience –

Eli Langer:

At this point, you guys are just reminiscing about your previous relationship, and I’m just a bystander. But go ahead Zevy.

Zevy Wolman:

So, I did a lot of really stupid things, and what I would tell people is that we don’t know when we’re going to have to grow up. And, of course, everybody’s family should be healthy. But the best thing you could possibly do is equip yourself to make decisions with your eyes wide open. Because so often we’re forced into situations for many, many, many reasons. Even when somebody leaves yeshiva and suddenly they’re in business. What does it mean to be in business? It means you’re taking somebody else’s money, most likely. To start, you’re taking a family member’s money or whatever it is to start. And suddenly you’re making decisions, which with what is effectively mamon hekish, money which is holy. It’s not yours, you have no responsibility for it.

And so, the fact that people don’t have secular education. I can’t change that, we’re not changing the system. We’re not commenting on the system. But that’s not a reason not to educate. That’s not a reason not to learn and to take the time to equip yourself to make the smartest decisions possible. No matter what you choose to do in life, whether you’re staying in kollel until you’re 35 or whether you’re starting to work at age 22, there is no excuse not to be well educated. I almost lost everything a couple of times because I just didn’t know. And there’s so many things that I wish I would’ve done differently. But I think, David, again, what you did with your question was fantastic because it painted a really acute picture of the reasons to self educate. So –

David Bashevkin:

And I love that line, you said, I’m paraphrasing, but, “You never know when you’re going to have to grow up.” And I think as a community, we are now learning that the time to grow up is actually right now. Eli, given your experiences with Kosher Money, how have you changed your personal relationship with finances and particularly the way that you are educating your own children about money, or plan to educate your own children about money?

Eli Langer:

So, Zevy’s very humble. He has quite a few organizations and companies he’s involved with. I know him for about eight months. Every month I find out about another organization he’s involved with. One of them is –

Zevy Wolman:

Can you mute him?

David Bashevkin:

Keep going.

Eli Langer:

One of them is actually called The Jewish Entrepreneur. And the reason I bring that up is because that is a non-profit organization that helps business owners get together with mentors for free to help them not make the same mistakes that they’ve made, to help them guide them in their own business. And the reason I bring it up is because I think as much as we cry about the current scenarios, as it pertains to finance, we have so many resources available to us that can help us. Whether it’s educating our children or helping us within our own personal finances or within our businesses. The amount of YouTube videos that you can watch to get whatever education you need related to personal finance or your business are plenty.

There so many apps out there, whether you need a budget, Tiller, Mint, to help you manage your finances. There’s never been a better time in the world to do that. And a lot of it can be automated, right? I get an email from an app called Tiller every day showing me what all my credit cards, debit cards, savings, everything that happened in the previous day. And I’m more educated because of that, I’m using technology to help me. I have a debit card for my oldest, he’s 11. Now, does he go out and about and spend? No. But it’s a smart debit card that allows him to get some sort of allowance. It teaches him a little bit about money. That didn’t exist 10 years ago, having mentors.

Don’t make the same mistakes other people made. Ask people, it doesn’t need to be through The Jewish Entrepreneur. Ask someone older, ask a parent, ask an uncle, ask an older cousin. Say, “Hey, here’s where I am.” It’s okay to have challenges, but it’s not okay to not ask the people closest to you that can help you through that. And I think if we distill that into the next generation to have this conversation or to use the technology given to us to make us better, I think we can get a long way into fixing the problem.

David Bashevkin:

I cannot thank you both enough, really for your work about helping individuals, families learn how to grow up. Because you never know when you are going to have to grow up. And really the time is right now and the friendship that you have shown to me and the graciousness you’ve shown to me and really what you’ve done for the Jewish community together has been absolutely remarkable. I always end my interviews with a little bit of rapid fire questions that I’d like you to weigh in on. I am a voracious reader. I was wondering, is there a book that has resonated with you related to personal finance, economics, investing? What book would you recommend for somebody who is looking to learn more about this?

Zevy Wolman:

Eli, you want to go first?

Eli Langer:

No, you go first.

Zevy Wolman:

Rabbi Daniel Lapin, Thou Shall Prosper.

Eli Langer:

Oh, he was on Dave Ramsey actually. Or at least he became very good friends with Dave Ramsey, right?

Zevy Wolman:

Yes, yes.

David Bashevkin:

Daniel Lapin, Thou Shall Prosper. Okay.

Zevy Wolman:

And basically the idea is you cannot divorce Hakadosh Baruch Hu, you can’t divorce God from money. The Torah is replete with how you can utilize money to become a better Jew and to become a better human being, tzedakah and helping other people. And it’s a complete perspective changer on –

David Bashevkin:

So you’re putting the Torah as your second book recommendation, after Thou Shall Prosper?

Zevy Wolman:

Yeah, that’s what I said. Yeah, exactly.

David Bashevkin:

Eli Langer, what is a book that you recommend that you have found helpful in understanding more about finances?

Eli Langer:

So, this book is actually from Rabbi Naftali Horowitz. He wrote an amazing book, it’s almost like a mussar sefer. It helps you tap into the potential that you have. It’s called, I believe, Prosperous You, or, You Prosperous.

Zevy Wolman:

You Revealed, I think.

Eli Langer: