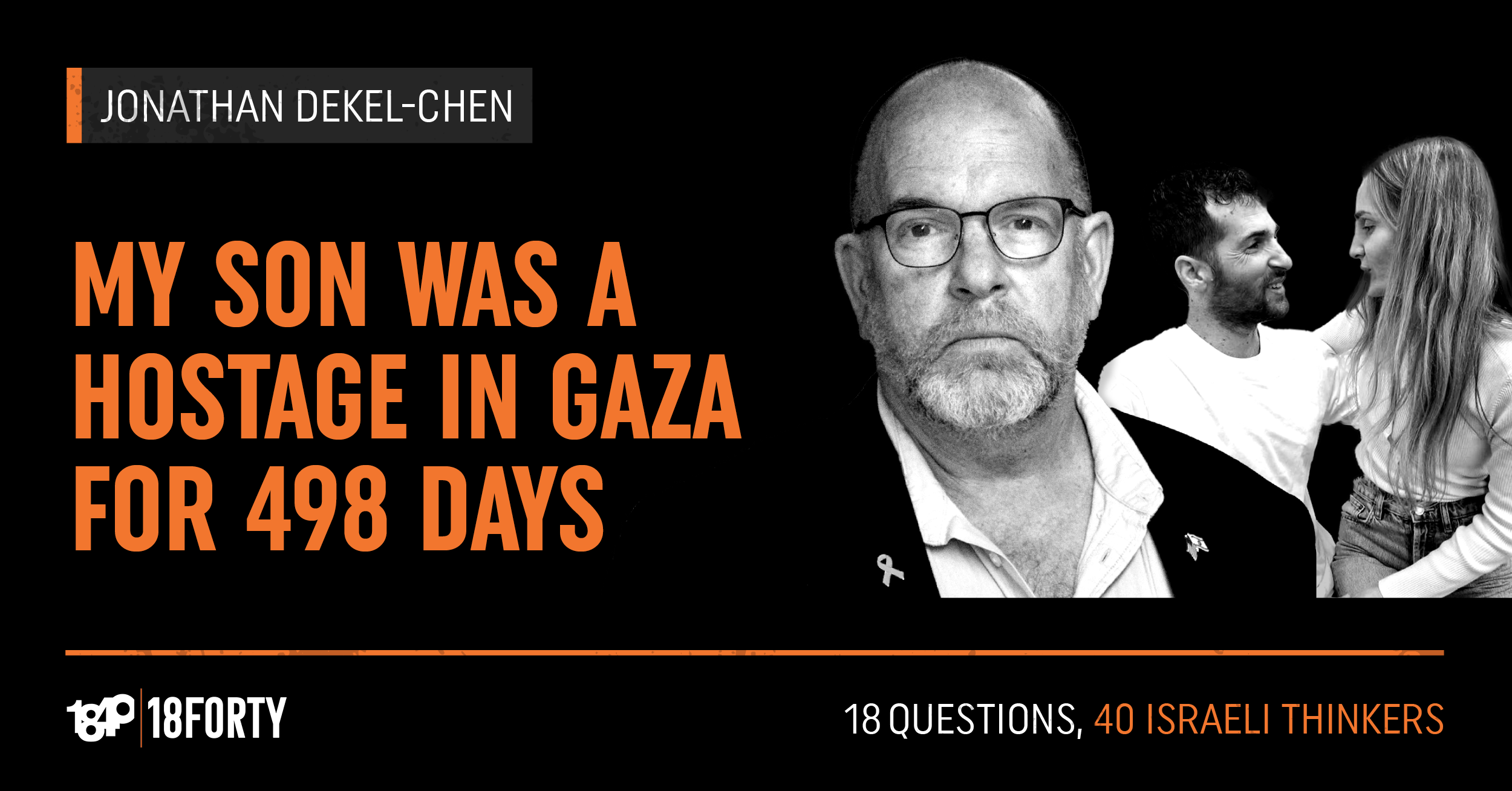

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: My Son was a Hostage in Gaza for 43 Million Seconds. He Felt Every One.

Sagui Dekel-Chen was held hostage in Gaza for 498 days—or 43 million seconds. He came home on Feb. 18.

Summary

For more 18Forty:

NEWSLETTER: 18forty.org/join

CALL: (212) 582-1840

EMAIL: info@18forty.org

WEBSITE: 18forty.org

IG: @18forty

X: @18_forty

Transcripts are lightly edited—please excuse any imperfections.

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Sagui he told us, once he was home, that he had no news from the outside world. And on the contrary, what he had seen, what his eyes told him, when he left the kibbutz, that no one was going to survive. No one. It was very hard for him to think about such things in his waking hours, in Gaza, in the tunnels.

But his dream world was almost identical to Avital’s for almost 500 days. Wow. They lived an entire life together for that year and a half, dreaming simultaneously about life with the other. It is a miraculous thing.

Sruli Fruchter: From 18Forty, this is 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers, and I’m your host, Sruli Fruchter. 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers is a podcast that interviews Israel’s leading voices to explore those critical questions people are having today on Zionism, the Israel-Hamas war, democracy, morality, Judaism, peace, Israel’s future, and so much more. Every week, we introduce you to fresh perspectives and challenging ideas about Israel from across the political spectrum that you won’t find anywhere else. So if you’re the kind of person who wants to learn, understand, and dive deeper into Israel, then join us on our journey as we pose 18 pressing questions to the 40 Israeli journalists, scholars, and religious thinkers you need to hear from today.

The makeup of this podcast is, at the same time, very expansive and also very limiting. So within this show, and separate from our standard 18 questions and our planned 40 Israeli thinkers, we are including a special series interviewing mishpachot hachatufim, the families of the hostages. A few weeks ago, I was speaking with my good friend Ariella Goodman, who is heavily involved with the hostage families, and actually wrote an essay for 18Forty about this called, We Must Learn the Hostages’ Names and Tell Their Stories. And during our conversation, she initially proposed the idea to me that we should find a way to include the hostages’ families in our series.

And obviously, there are issues with bringing on families who are in the midst of such terrible trauma and tragedy, and asking them general questions about the war, Israeli democracy, and the future of this country. And the reason that I now want to include them in this series is both related and unrelated to the podcast’s primary aim. It’s incredibly tone deaf, in my opinion, to bring on hostage families and then ask them all those general questions, which are very, very important, but are still unrelated to their immediate trauma, tragedy, and healing about Zionism, the conflict, and everything else happening in the world. But at the same time, and this is something that I felt for a very long time, but didn’t know that there was any way that we, in particular, could address or accommodate this.

I think we are missing something crucial about the discourse happening within Israel, the voices gathering people in Israel. If we are not listening and elevating the voices of those whose loved ones are trapped or were trapped in Gaza by Hamas since October 7th. So I’m hoping that this miniseries will allow us to get a deeper sense of what hostage families are experiencing, thinking, hoping for, and struggling with as we try to enmesh ourselves into Israeli society and all of its conversations. So there will be a handful of interviews with families of hostages, some who were released, some who were killed in captivity, and some who are awaiting their release.

And these are not going to be part of the count of 40 Israeli thinkers that we have, and we will not be asking them our standard 18 questions. Instead, as I mentioned before, these interviews will be geared toward platforming them and their perspectives. And with that, we can now begin with today’s episode.

Sagui Dekel-Chen was taken hostage by Hamas on October 7th, 2023 from Kibbutz Nir Oz, which suffered some of the worst devastation from the gruesome and barbaric terrorist attack of October 7th.

Sagui was brought home from Hamas captivity on February 15th, about a month ago, after nearly 500 days of captivity. As part of the first phase of ceasefire deal between Israel and Hamas, he came home alongside Sasha Trufanov and Iair Horn. Sagui is an American Israeli citizen who, when he was first taken captive, had a pregnant wife and two daughters. And until two days before he was released, Sagui had no idea what their fate was.

He didn’t know if they were alive, in part, in whole, what happened to his wife’s pregnancy, and thank God he came home to his whole family, plus a new daughter. In this interview, I speak to Jonathan Dekel-Chen, Sagui’s father, who has been tirelessly advocating for Sagui’s release every single day since they first discovered that he was taken hostage. And now, Jonathan continues to advocate for all the hostages’ release, and in specific, he feels a particular responsibility towards his kibbutz, Kibbutz Nir Oz. When Sagui was released, there was an incredibly heartwarming and moving video of him reuniting with his wife, and I believe very soon after, singing a touching song to reinstate hope where it has been so defeated, and we’ll play a bit of it right now.

Jonathan is a father, grandfather, husband, and dedicated member of Kibbutz Nir Oz, and in his professional life, he’s the Rabbi Edward Sandrow Chair in Soviet & East European Jewry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. There are so many dimensions of our conversation, speaking about October 7th, everything that has happened since, the state of Jonathan and his family, what those nearly 500 days were like, and where they move from here. I hope you enjoy our conversation.

Jonathan, thank you so much for giving us your time and giving us your space to speak about your experience over the last 500 plus days.

Since October 7th, I want to actually begin in an interesting place. Your father was a Holocaust survivor, and your son and your daughter-in-law and your grandchildren and your ex-wife were October 7th survivors. What is that like for you to have carried the history, and also as a historian, to have carried the history of the Holocaust, to come to Israel after high school and after October 7th to see what your family has gone through?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Well, it’s a good question, and one that, of course, has occupied my mind. The subject has occupied my mind for these last 500 plus days, but it really began on October 7th itself.

I heard the news in real time of what was happening on our kibbutz, Kibbutz Nir Oz, at about 12 p.m., 12.30 p.m. Israel time. I was abroad at that moment, and three things occupied my mind at that moment. One, of course, was concern for my family on Nir Oz, and not really knowing, not being able to gather information very quickly. So that was my first concern.

My second concern or thought was that once it became clear the degree of the catastrophe that was happening all along the border, Nir Oz being ground zero but all along the border, my second thought was what a strange stroke of luck that a residential boarding school for the arts that Sagui, my older son, and Tamar Kedem, who we may talk about a little later, we had founded that school, that residential boarding school in 2014 in the midst of Operation Protective Edge, and it was all of two kilometers east of where our kibbutz is. And I thought to myself, what a strange stroke of luck that it had been moved, the residential boarding school, a few years earlier, because if those kids, teenagers, had been there that weekend, over that weekend, they too would have been massacred. And the third thought that I had to get to your question was, and I remember this and made me shudder then, it still makes me shudder 500 and plus days later, is I was just glad that both of my parents had already passed away years ago and didn’t live to see this. And they lived in the States, they never made Aliyah, but they were Zionists at heart.

And particularly as a Holocaust survivor, my dad and a refugee from Nazi Germany, my mom, they were incredibly proud of Israel. They were proud of me, us living in Israel on a border kibbutz. And although they never made the choice to come live in Israel, it was a central theme in their minds. And I think it would have been utterly crushing to them.

It would have killed them had they been witness to what happened on October 7th. Despite the fact that there was a sovereign Jewish state with a supposedly infallible army and intelligence services, and that their son and beloved grandchildren were being consumed by this. And it has been with me ever since that thought.

Sruli Fruchter: Were your parents ever concerned that something like this may happen?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: I think any sane person would be, rational person would be consumed.

Your listeners probably know that along the border with Gaza, there’s never really been peace. There have been ups and downs since the late 1940s, early 1950s with fedayeen raids, terrorist raids across the border from then Egyptian controlled Gaza. And it never completely ceased. That being said, from late 2007, early 2008, with the Hamas coup in Gaza and their forceful takeover from the Palestinian Authority, the violence intensified just way off the scale.

And so anyone loved us, even liked us, regardless of where they were, were always very concerned because we were the target of monthly, weekly, sometimes daily rocket attacks, sniper fire, attack tunnels being dug towards our kibbutz from Gaza, explosive kites and incendiary balloons being flown over, and mass protests, mass violent protests at the border, all of one mile from our homes. So it was a constant drumbeat from all quarters of my family in the States and even family members in Israel who lived elsewhere. Our belief was it was our job to be sort of guardians of the border, civilian guardians of the border, to have that Israeli Jewish presence along the border, to be the breadbasket of Israel, which that part of the country certainly is. And really living the initial Zionist vision of what people who serve the country are supposed to do, we certainly were aware and prepared for the possibility, the vague possibility of infiltrations of individual terrorists from Gaza or small groups.

Our thinking was always, and it was the unwritten agreement between any border community and the state, meaning the government and the army, that if we ever needed their help in terms of a larger scale incursion, they would be there. They would be there to help us, to rescue us. And October 7th, that never happened.

Sruli Fruchter: Can you say more about that?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Across the southern part of the country on October 7th, there were many, many points of border breaching by Hamas terrorists and thousands, many, many thousands of civilian looters coming over from Gaza.

Of course, there was a horrific massacre at the Nova Festival and in a number of army outposts. What is less spoken of, for reasons that I don’t really understand, were the assaults on the kibbutzim along the border. On Kibbutz Nir Oz, my son and others spotted the first terrorists who had breached into Nir Oz at around 6:30 in the morning. And they gave the alert to the population or the community, a little over 400 people, that there were terrorists.

He only saw a small group at that time. He was in one particular place at one particular moment. He couldn’t have known that simultaneously hundreds of highly trained, heavily armed terrorists were in the kibbutz. He put out the alarm.

The security team for the kibbutz mobilized a small group of volunteers, just regular people who serve as security team and also like civil defense. And during COVID, these same guys were those who were distributing food as we were all sort of in lockdown in our homes, they distributed food on golf carts to the population and also the fire brigade if necessary. And so they were mobilized, but immediately it became clear that the kibbutz had been overwhelmed. And we now know that all of the members of the security team who were able to exit their homes and try to defend the kibbutz were either murdered that day or taken hostage and subsequently murdered.

In all of the other kibbutzim that were breached, Be’eri, Nahal Oz, Kfar Aza, the army or soldiers, not necessarily in any organized fashion, but soldiers and police units arrived in the subsequent hours and did battle with the terrorists. It took many, many hours for them to subdue all of the terrorists in those other kibbutzim. What that wound up doing, however, in those other kibbutzim is restricting the mobility of the terrorists. They were confined to a neighborhood or two in those kibbutzim.

The rest of the kibbutz was basically untouched, perhaps a public building here and there. Neroz, it’s a completely different story. The first army units arrived on Nir Oz at 2.30 in the afternoon on October 7th, which was approximately one hour after the terrorists and all of the looters had left the kibbutz. We don’t know why.

They could have stayed for another hour easily, rampaging with no one to defend the kibbutz. Our security team by around quarter to nine in the morning was either dead or having been taken captive. So the terrorists were able to rampage throughout the kibbutz. So unlike the other kibbutzim where there are a couple of neighborhoods that were affected on Nir Oz, they rendered our entire community uninhabitable.

80% of all of the buildings on Nir Oz were either completely destroyed or sustained such damage from the process of that massacre and explosives and RPGs being used and heavy machine guns being used that a total of 80% of all of our buildings have to be destroyed. They’re uninhabitable. Most of the infrastructure is gone. There was a mass murder conducted on our kibbutz.

As I said, a little over 400 people, about 45 of them were men, women, and children were murdered on October 7th. Today we know that the total is at least 59, including murdered people from October 7th whose bodies were taken with the Hamas and the Islamic Jihad. We assume for bargaining chips on October 7th and others who were murdered, taken alive from Nir Ozand subsequently murdered in captivity. So we now have 59 total murder victims from our very small community and still 14 members of our community are still in Gaza.

Sruli Fruchter: The destruction towards Nir Oz and towards all of its members is atrocious. And Sagui was taken hostage on October 7th and returned home, thank God, I believe about a month ago.

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Yeah, February 15th, 14th, February 14th.

Sruli Fruchter: How is Sagui doing now? What’s the past month of healing look like for him?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Well, it takes a long time to rebound and correct the damage of 500 days with no sunlight whatsoever.

This is for all of the hostages who emerged from the Hamas terror tunnels. No sunlight, close to starvation, very little if any medical care, sanitary conditions that we’re better off not imagining, and the threat of imminent death. Sagui calculated he was a hostage for 43 million seconds and he felt every one of them. Danger of imminent death from two sources.

One, of course, his Hamas captors. And we know for a fact that in some situations, Hamas terrorists have executed hostages for a variety of reasons, some of which we may never know. But also, and this is really important to understand, he had a number of near-death experiences while being held captive in Gaza from friendly fire, meaning bombs dropped or artillery shells landing in Gaza, shot or dropped by the Israeli Air Force or Israeli artillery. And we hear this repeatedly from released hostages.

This should have debunked completely the idea that more and more warfare will get hostages home. There is zero proof of concept that any hostage can be freed, alive certainly, and perhaps even the remains found solely through warfare. The only thing that will do is kill more hostages and lose any chance that we have of recovering bodies. And if you have any doubts, ask any of the hostages who have returned from the tunnels and they will say exactlythe same thing.

Sruli Fruchter: Was Sagui aware of what was happening over the last 500 days while he was in captivity? How did he get information or find out what was happening?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Well, we were unpleasantly surprised to hear in earlier releases of hostages, those who were held above ground almost exclusively, so that would be mostly women. We had heard, all of us heard, that they did have some access to news of the world by way of their Hamas captors, or they’d actually heard broadcasts, radio broadcasts, internet, TV. So they were able to keep up in some measure and sometimes even see their own family members in protests or appearing in all sorts of platforms. In the case of Sagui, and this appears to be a universal truth, with those hostages who emerged from the tunnels, he had absolutely no word of the outside worldtwo days before he was freed.

So in his case, what that meant was, he was taken from the kibbutz. We approximated around 11:30 in the morning on October 7th, driving towards Gaza, badly wounded. And what he saw was the kibbutz going up in flames, and he had already seen bodies lying everywhere. His assumption was that his wife, or we’ll put it differently, he had no idea on October 7th, whether his wife, seven months pregnant at the time, two daughters, his mother, his sister, her husband, and another two little boys, and all of his closest friends, if they were alive or dead.

He then spent the next 495 days not knowing if any of them had survived. Honestly, I don’t know how he did it. And we had hoped the entire time that somehow or another, and we were encouraged, again, by the reports from the hostages who had come back a year and three months ago now, that they were hearing some news. So we were very consistent in appearing in various news platforms, Israeli and abroad, to try and get that message to him, that his daughters had survived, that his wife was okay, that his mom and sister and their family were okay.

And we, as I said, we were unpleasantly surprised, shocked really, to hear that he knew nothing of it until two days before.

Sruli Fruchter: What happened two days before he was released?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Two days before he was taken from a room, underground room, that he had been held in with some other hostages for-

Sruli Fruchter: Was that a standard tunnel, as is normally depicted, or there was a room within a tunnel?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: It was one of the above. I really don’t know. In any case, he was taken from that space that he was being held and moved to sort of like a preparation room where he was allowed to clean up.

They were well-fed, those hostages that were about to be released. And there were also, there was some background noise of TV, I believe, and podcasts and things like that. And he was able to ascertain from that that his wife and two daughters, the older ones, had survived. He didn’t know about his mother.

He didn’t know if his wife, Avital, had given birth. He knew nothing about the rest of the kibbutz, but that he was able to reconstruct. He found out positively about them the moment he crossed the border, the border between Gaza and Israel, the handoff between the Red Cross and the IDF. And through pre-instruction from us, the IDF officers who received him told him immediately that Avital had survived, along with the two older girls, and that she had given birth to their third daughter.

That’s what he knew when we met him.

Sruli Fruchter: I want to briefly return to the day of October 7th. You weren’t in Israel at the time. I believe you were in a conference in Baltimore, if I’m not mistaken.

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Yeah, I was on my way to an academic seminar in Baltimore at that moment.

Sruli Fruchter: When did you realize that something was wrong and that Sagui was taken hostage?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Well, I kind of have to answer them separately.

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah.

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: My wife and I were woken up by a friend about five in the morning, Baltimore time that day, who I guess was having trouble sleeping.

And that person, who lives in Rhode Island, an old friend of both of ours, had been watching CNN or some other news channels, and was familiar with Israel in general, and Nir Oz in particular, and asked us, what’s going on on Nir Oz? And I had no idea what she was talking about. So I turned on the TV and was looking, of course, at the Israeli websites, and saw immediately that there was a major assault by Hamas on the southern part of Israel. I then tried calling my kids on the kibbutz. Took a while, because at that moment, they were all still hiding in their bomb shelters, where reception is very poor.

On a good day, it’s very poor. And they were, in fact, hiding from Hamas terrorists in their own homes. Took a while, but at around 12:30 Israel time, so that would be 5:30 Baltimore time, I was able to get a hold of my son-in-law, who was in a bomb shelter with my daughter, their kids, some guests who had come from outside the kibbutz, and my ex-wife, the mother of my children. And we could only speak very, very briefly.

They were running out of charge in the phone, and he told me that there was a massacre going on on the kibbutz. They had lost contact with Sagui and Avital much earlier that morning. He couldn’t say what their condition was, and that my ex-wife was pretty severely injured in shrapnel wounds. There’s a story in itself.

There were two women from Nir Oz who were taken captive. Many were taken captive. We had a total of 79 hostages on that first day, taken from Nir Oz, again, out of a total community of a little over 400. My ex-wife, her name is Neomit, and one other woman, Bat-Sheva Yahalomi, whose husband we buried just a couple of days ago.

They were taken captive, along with others, and each one in a strange series of events, and through incredible heroism, were able to rescue themselves. In the case of Bat-Sheva, she was able to rescue herself without injury, and one of her children, the other son, was taken by Hamas and then was returned in the first agreement in late 2023. My ex-wife was severely injured and full of shrapnel, essentially bleeding out as she crawled her way back from the border fence between Israel and Gaza, through our fields, and eventually was able to get back into the kibbutz and to our daughter’s home, got into the bomb shelter with the family, and my son-in-law and his brother saved her life, saved her from bleeding out.

Sruli Fruchter: When did you figure that all out?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Well, go a little bit back to the chronology.

As we said, I was able to speak with my daughter Ofir and her husband at around 12:30. The next time I spoke with anyone was at around 4:35 PM Israel time, at which time the army had arrived in force at Nir Oz. They never fired a shot because there was nobody to shoot at, as I mentioned before. And the army, together with some adults on the kibbutz, systematically went through the kibbutz to find survivors and to disarm booby traps that were left behind by the terrorists.

As they collected survivors, they centralized them all in one hardened building on the kibbutz in preparation for evacuation. Once they arrived in that building, thankfully, the generators did work there and they were able to recharge their phones. So starting at about 5:30, 6 PM, I was able to start speaking again with my daughter. My son-in-law was out on those missions to rescue people and recover bodies.

A horrific task, unspeakable, really. And from there, I was in fairly consistent contact with them. The story, the saga, the heroism of my ex-wife, I began to understand, I think later that evening or the following morning, as they were being evacuated to Eilat. My ex-wife was sent to a hospital with other people from the kibbutz who had sustained injuries during the massacre.

Sruli Fruchter: When did you realize that, yes, Sagui was taken hostage, but that he wasn’t going to be coming home in a week or even in a month, that it was going to be a sustained battle to bring him home?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Well, we didn’t really know that he was a hostage at first. He was simply missing. In some cases on Nir Oz, there was evidence of people being taken hostage. Either one of the survivors saw them being taken hostage somehow or another.

The other way was through Hamas videos, as we know and we knew that day. Terrorists, a lot of them had body cams on and there was an embedded reporter. Most of the footage of the massacres on the kibbutzim taken by Hamas were taken on Nir Oz. There was an embedded journalist and photographer.

And in many cases, there was visual material to show that this or that person from the kibbutz was being led into captivity. But there was a pretty large chunk of people who were simply missing. Their bodies weren’t recovered, but there was no evidence of them having been taken to Gaza. And that’s what the army, that’s what the state considered them, I believe for about two weeks, most of them.

And eventually through intelligence sources, the army was able to confirm for us and many other families that our loved ones were hostages, but they had no information about them if they were alive, dead, wounded. Look, my expectation was always that our government, or my hope, we’ll put it this way, my hope was that our government would do everything in its power, everything in its pow er to get the hostages back. And anyone who’s lived in Israel for more than a minute and a half, it knew that that was going to require at some stage, particularly once we understood that we weren’t talking about just the hostages from Nir Oz, there were 240. The only way they were coming home, any of them would probably come home alive, is through a negotiated process with a terrorist organization or multiple terrorist organizations, really.

Our expectations in Israel would be that the government would mobilize every resource to get to negotiate the hostages back home, and that would necessitate an exchange of some kind of Hamas terrorists and others. Exactly how many, when, it wasn’t for us to say. And then we had that first stage of release, a little over 100 women and children, a couple of men were released. It was our hope that that would continue for the release of all the hostages or as many as possible.

But from early December, if we had any doubts, early December, 2023, if anybody had any doubts before, it became painfully clear to us that our own government really wasn’t interested in continuing negotiations to enable hostage release. And from that point on, I put aside this thought of, okay, when will we be able to get these hostages released and just focus on the work itself of mobilizing an advocacy campaign or being a part of an advocacy campaign in Israel and abroad, mostly in the US, because it was clear that our government, the Israeli government, without massive public pressure and mobilization of political assets from abroad, would never agree to negotiate with Hamas truly, really and truly, to get all of our loved ones home, whoever was still alive in the bodies to return to their loved ones.

Sruli Fruchter: Do you remember the moment that your posture of hope shifted and that you had to mobilize into a posture of advocacy?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: I think from the very beginning, we, unfortunately, it was incumbent upon the families and any others in Israel or abroad who believe that the first priority, whatever we were going to do to Hamas, the first priority, not just as families of hostages, but as Israelis, as Zionists, as Jews, the first priority had to be the return of captives. And so in Israel, within a day or two, there was already an ad hoc, out of nowhere, ground up advocacy network created, an organization for that.

There were a lot of mistakes made along the way in that organization in terms of their strategies and how to approach this mission of public advocacy in Israel and abroad. I joined it a little later. I was not amongst the founders of it because as a member of a kibbutz that had been destroyed and the level of the human cost of that massacre, I was completely consumed, I would say for two or three weeks. And once I got back to Israel, which is a couple of days after October 7th, I was consumed completely with just the health of my family that had survived the massacre and the wellbeing of our surviving kibbutz community.

That was all happening in Eilat. The surviving community was evacuated on October 8th in the midst of a war to a hotel in Eilat where we were housed very graciously until early January, when we pretty much on our own initiative, the government was sluggish to say the least on our own initiative, moved about 80% of the surviving community to temporary housing here in Kiryat Gat, which is where we’re speaking right now. And as far as Sagui’s wellbeing was concerned, we didn’t know anything really until late November, early December of the 104, I believe hostages were released in that first tranche of negotiation, 40 of them were from Nir Oz, women and teenagers and actually little children as well. And a handful of them had encountered Sagui in the tunnels just before they were released.

And they were able to tell us positively that he was alive, which was a huge relief. We simply didn’t know for three months if he was alive or not, and that he was wounded. He had been wounded in his shoulder and in his leg, which we had already ascertained from the forensics in and around his home that he had been injured, but they had gotten some kind of medical treatment. And really that’s all we knew in terms of definitive information about Sagui’s condition until he walked out of that white Hamas van or minibus on February 14th in Khan Yunis.

Sruli Fruchter: The first Holocaust Remembrance Day after October 7th, you wrote a very interesting article about comparing the Holocaust to October 7th and what gets lost in that type of comparison that people make. One of the things you mentioned was how it was particularly difficult to try and highlight the urgency of bringing Sagui home because he was an adult man. And I’m curious what your specific route of advocacy to bring Sagui home has looked like and what the particular difficulties have been as a father advocating for an adult male who is often left behind when people are thinking of the hatufim or the hostages that need to come home.

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Sure.

Sagui was one of eight U.S. hostages remaining in Hamas and Jihad captivity following the release of the women and children. I had already ascertained before that, that as dual U.S.-Israeli citizens, the main address for my personal advocacy would be in the U.S. At first, the Biden administration, and as of last November, the Trump administration, and for a while, both of them together. So that was really my main avenue, understanding understanding the landscape in Israel, the political landscape in Israel, that the only way to get this government, our Israeli government, to yes on any agreement to release hostages, that would be through Washington, D.C., and the force of the U.S. administration in Congress. And nothing that’s happened since then counters that understanding that I had back in October of 2023.

I don’t say that with any pride as an Israeli, but that is a fact. It’s also important to note that my advocacy has always been not just for Sagui, not just for the U.S. citizens, for everyone. I understood that the only way that Sagui or U.S. citizens, or citizens of any other country, were going to get out if a comprehensive deal was made. And I think that’s borne itself out until now, barring Russian citizens, which is an entirely different, you know, I can put on my other professional hat as what was once called a Sovietologist, but we’ll leave that for another day.

And the Thai workers, which again is a very different category. The importance of pressure from Washington was the only way any release was going to happen. As ideas were being floated for a more comprehensive release, it became clear that one of the categories that Hamas was thinking about in terms of a staggered release, which is the way things developed. It’s not an American idea.

That’s from the Israeli government. This idea of not everyone at one time, but rather stages. Those categories sort of came about as a result of that approach to possible negotiations. And Sagui, while indeed a 35 and 36-year-old male, what Hamas would consider of military age, he was wounded.

He was wounded. We knew that immediately. And, you know, it turns out that, you know, those wounds were significant. So at least for us, that meant that he wouldn’t, would perhaps not be at the end of the line in this staggered negotiation.

I was prepared for any outcome, again, because for me, it’s about everyone, starting with Sagui, people from my extended family from the kibbutz. I mean, anyone who knows anything about a kibbutz, particularly a smaller one, which is a border community, knows how woven we are in the fabric of one another’s lives. And so whether it was 34 at one point, kibbutz people remaining in Gaza out of a larger number of hostages, or if we’re down to 14 now, and Sagui is already home, he’s been home now for three and a half weeks. For me, the fight will never be over until those 14 are home.

And of course, the rest of the 59. It was always unclear what the value was of Sagui being an American citizen. I still really don’t know. The value for who? For Sagui, in terms of his release date.

What I do know is that being a US citizen allowed me and the other US citizens, of course, their families, access to the US administrations, and to the halls of Congress, and also to Jewish and major Jewish organizations in the United States in North America. So that certainly was, I guess, an added value to the advocacy work that I had done and will continue to do.

Sruli Fruchter: You have a lot of different roles and identities outside of your particularly work for Sagui. Over the 495 days when you were fighting for Sagui and fighting for all the release of all the hostages, how did your role as a father, as a grandfather, as a member of Nir Oz, where you said everyone’s part of your extended family to some extent, how did that change? And what did that look like?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Well, you know, in my family’s case, our nuclear family, I have three other kids who all have their own young families.

My ex-wife, my current wife, who lives in the States, we all took on roles of getting through this. Those could be childcare, those could be working more closely with the kibbutz administration. Because of my background, my role was mostly working on the hostage issue in the best way I could figure out. What that meant in practice was that I was traveling a lot in Israel, but mostly abroad.

Over the course of those nearly 500 days, I would say at least half of them were spent in the States, shuttling Washington, D.C., New York, down to Florida on occasion, and just working this issue the best I could. So my grandkids, they bore the brunt of this, me not being around a lot, but it was clear why. Was that hard for you? It was really hard. We’re a closely knit family.

I have 13 grandkids and adore them all. And I had my role as grandfather until October 7th. So it was difficult, but there was a greater good that had to be done here. And surprisingly, the grandkids who were old enough to understand these things completely got it.

And we’re as supportive as 10-year-olds or 8-year-olds or 5-year-olds can be around this because they dearly wanted their Uncle Sagui back, needless to say, their dad. And the dads of many of their friends, they understood how important it was for me to be able to go and do that and for them to be cool with it. And my kids were also great around this.

Sruli Fruchter: You said that you guys are a very tight-knit family.

How did you preserve Sagui’s presence while he was gone for so long? How did you keep him, even though you knew that he was alive, how did you keep him alive as if he was with you? He

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: was never anything else, but with us every moment. His wife has really described this for herself. And I invite your viewers, your listeners to seek out her. There’s plenty in English as well, you know, articles about her and interviews.

For her, Sagui was with her every moment, mostly in her sleeping hours, in her dream world.

Sruli Fruchter: Can you say more about that? It’s fascinating.

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Well, it’s really quite extraordinary. And we knew one half of the story before February 14th, and then the other half only became clear thereafter.

Avital is described how for her, she was essentially functioning as a single mother with a lot of help from family members and so on, but a single mom and manager of a business for nearly 500 days. Her home was gone. Our way of life was gone. A very unclear future in terms of where we’re going to live, how we’re going to live.

But for her, Sagui was with her all the time, especially in her dream world. She was too busy with the stuff of life during the waking hours. But he was with him every night, all night, in her dream world. I again invite your audience.

A song was written about this, her words put to music by a very prominent Israeli musician. I invite you to put a link to this song, about her story, their connection in her dreams, and really having to deal with that transition every morning of having to say goodbye to Sagui, or so long, not goodbye, until the next night, sundown, more or less. That’s one half of the story. The other, perhaps even more extraordinary half of the story is that Sagui told us once he was home that, as I mentioned before, he had no news from the outside world.

And on the contrary, what he had seen, what his eyes told him when he left the kibbutz, that no one was going to survive. No one. It was very hard for him to think about such things in his waking hours in Gaza, in the tunnels. But his dream world was almost identical to Avital’s for almost 5 00 days.

They lived an entire life together for that year and a half, dreaming simultaneously about life with the other. It is a miraculous thing. And I can’t explain it rationally. I don’t think anyone can.

But that is how, and for all of us, I believe, in the family, we had our versions of that.

For me, Sagui and I, since he was a little boy, have done lots of things together from what dads and their sons do when they’re very young, playing baseball, teaching him baseball, playing, you know, a lot of sports, a lot of bike riding, and then in his adulthood, oh, and Sagui spent a lot of time with me on the kibbutz out in the fields. As he was growing up, I wasn’t a professor of anything. I was the manager of the agricultural machinery shop on the kibbutz, which is a huge enterprise on the kibbutz like Nir Oz, which is completely mechanized.

And, you know, we farm over 10,000 acres in any given year. So he was with me a lot. And then in adulthood, he began a series of projects converting old buses into usable objects.

Sruli Fruchter: Which he was doing on the morning of October 7th.

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Yes, he was. And he was, in fact, that next day was going to deliver two converted buses to the owners of these buses. He had from old airport buses to mobile technological classrooms meant to serve underserved communities in the peripheries of Israel. It’s with an educational nonprofit called Ofanim, and they’re driving around the country as we speak.

And we had also, after he finished his service, he worked with his older brother, Itay, and with Tamar Kedem, soon to be Tamar Kedem Simantov, worked with us on creating a youth village, a national youth village for the arts in the Eshkol region. But it was a national village where we intended, and in fact made happen, a residential boarding school for kids from throughout the periphery, high school students in Israel. So that would be geographic periphery, but also socioeconomic periphery for them to get a world-class education in the arts, professional training in their high school years, so that they could make their own choices later on, whether or not they wanted to go into a career, pursue a career in the arts, or go off and do other things. But closing the gap in Israel, which is perhaps a subject for some other time, the enormous gaps in Israel between the have and the have-nots, based mostly geographically, but not just, that we were trying to correct in our own little way.

Sagui’s job in that wonderful project was as a project manager. And so we worked in close contact for a couple of years, really sort of shoulder-to-shoulder building this youth village from nothing, from, you know, my wife likes to say sort of from paper clips and duct tape, which is kind of the way we created it, you know, total improvisation. So Sagui and I have always, in a way, completed each other’s thoughts and breathe the same air, as it were. And very often I asked myself over the last year and a half, I think a lot of us did, what would Sagui do now? What would he do now to advance the cause of the hostages or help their families? And those of us who knew her and loved her dearly asked that same question about Tamar Kedem Simantov.

What would Tamar have done right now to bridge this problem, to solve that challenge?

Sruli Fruchter: What was her answer usually?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Think creatively, think creatively. There are no boundaries as to what can happen. Think creatively, think methodically, think of outcomes in that process. And for me, in a way, it’s kind of cyclical because it’s the stuff that I taught him, but he gave it back to me, really, over the course of this last year and a half.

Sruli Fruchter: And I’m sure that over the last year and a half, many people were trying to show up for you and people always have good intentions and are trying to comfort families of the hostages or families of those affected. Were there any things that you think are the absolute do’s and don’ts or things that you found comforting and things that you found very unhelpful that you wished other people knew about or even know about now? Because there are still so many hostages still in Gaza.

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: That’s a great question, but I think we can generalize it to how should good meaning people approach loved ones or people that they barely know in times of crisis or time of need? And the answer to that will be very personal. I can only give you my answer.

Other people will have different answers. Tell me what you can do. Don’t tell me how you feel at this moment. At these moments, again, this is just personal, a kibbutznik‘s answer, perhaps.

I don’t need your pity and I don’t need your glorification. If you want to help, then help. Then ask me, what can I do? Or think of it yourself. What can you do to move the needle for the hostages? Just do it.

Don’t interrogate me about, you know, my head is too full of crisis and sadness and any number of things for me to tell you what to do. Things are usually pretty clear cut. In our case, it was go to a demonstration, write your senator, write an op-ed, raise money for the destroyed kibbutzim, any number of things to do. Just do it.

And I didn’t need the chitchat. It wasn’t encouraging. I just felt more often than not that it was to satisfy a need of that person who was approaching me and not really to be of help. That being said, an awful lot of what happened to us and continues to happen in parallel to the tragedies and the horrors and the pain and the longing, endless little miracles.

Endless little miracles.

Sruli Fruchter: Such as what?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Such as what?

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah, such as what?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Just from the things that we’ve talked about. Why did the terrorists leave Nir Oz at 1:30 on October 7th? Nobody was chasing them out. The place was completely defenseless.

They could have killed dozens more. They could have taken captive dozens more, but they left. I don’t know why. So that would be just from the inception, the fact that two women did escape, that so many of those taken captive were able to come home alive.

And we hope as many as possible more. The fact that Sagui survived, his captors, for whatever reasons that we will never really understand, didn’t panic and execute them. That his captors versus captors of other hostages gave them enough food to somehow survive. It’s endless.

And there are no rational explanations. And I’m a very pragmatic guy. I fix peanut combines for the majority of my life. I’m not spiritual.

That being said, it’s clear to me today, and Sagui would say exactly the same thing, as well as Avital, there is some matter of faith going on here. Somehow or another, Sagui and Avital and me and so many others have been, I don’t know if fed is the right word, but bolstered and buoyed by some rather mystical combination of a whole ecosystem of prayer for the hostages, for Sagui specifically. And that crosses its prayers from Israelis, Jews in Israel, good wishes, hope, but also from Jews in the diaspora and non-Jews everywhere. I’ve been approached by thousands of people, Jews, Christians, and Muslims who have said, and I completely believe them, they were totally sincere, telling us about their prayer for the hostages in general and Sagui specifically.

No one, I didn’t tell them to do that. And the missing link in these innumerable small miracles within this catastrophe that befell us, again, near almost ground zero, I’m incapable, and I have a pretty creative mind of explaining it in any sort of rational way, other than that sort of ecosystem of faith that surrounded us, Sagui and Avital in particular.

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah, phrasing an ecosystem of faith is such a visual, it really captures. If you don’t mind me asking, has this changed your relationship to your Judaism or to your faith?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: No, it is not.

It is not. I’ve gone through, like most people, I’m sure, over time cycles, but no, but something protected something. Terrorists were in Sagui’s house for hours. It looks like a battle zone for some reasons that we will never know.

Avital, seven months pregnant, and the two little girls survived that attack. Whereas right next door or on the other side of the kibbutz, almost exactly the same scenario, it was a different outcome. Little miracles within a horrific, the worst possible scenario that one can imagine. Emerging from the valley of death is what happened from October 7th and for us until February 14th, but there’s still an awful lot of work that needs to be done.

Sruli Fruchter: And how has your relationship to the state of Israel been changed?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: There’s no easy answer to that question. I feel as a father, a member of Kibbutz Nir Oz, citizen in the South of Israel, as an Israeli patriot, I’ve invested my entire life in adult life, in the security of Israel and its wellbeing and its progress. I feel completely betrayed by our government. It began on October 7th because of the colossal failure of our government’s security conception as it’s said in Israel and also from the army.

And how could it be that our army was that incompetent, that incompetent before and on October 7th for that to happen? That for eight hours on Kibbutz Nir Oz, the only thing people could do on their WhatsApp is just ask, where’s the army? Where is the army? The army should have been there by everything we had come to understand and it was that unwritten contract. If there’s a breach in the border fence of any kind, their army units in the kibbutz within 15 minutes took nine hours and a massacre before the first soldier arrived. The army to its credit has taken accountability for what happened and has made great strides and has had in more recent months great tactical successes, whether in Gaza, in Iran, in Lebanon that have produced the best geo-strategic position of Israel in decades, if not ever. The sense of betrayal, however, has only deepened with our government and not just because of its incompetence that showed on October 7th, but in its subsequent decision-making and its complete lack of accountability about what happened or what led to and happened on October 7th and its complete self-interest, political, personal self-interests in its decision-making around the fate of the hostages since October 7th.

It is unconscionable and I almost don’t recognize the country in that regard politically. I made Aliyah in 1982. I never would have imagined in my worst nightmares that a government of Israel, whatever party, doesn’t matter, would have made the choices that this government has made since October 7th around the fate of the hostages, that government ministers could say the things that they have said about the fate of the hostages since October 7th. The fact that Benjamin Netanyahu has not visited Nir Oz or spoken in any way with the surviving Nir Oz community since October 7th, it is unconscionable.

So that’s sort of looking at it from above, looking at it from below, although that’s not really the term I’d like to use, or more broadly, what I have seen over the last year and a half, both at a personal, family, and collective level, is that the vast majority of Israelis, when given the opportunity, will choose the right thing, the human thing, the just thing, if not manipulated by our politicians, of all stripes, by the way. And that has given me faith in the people of the State of Israel. And I hope and pray, such as a secular person can do, that one kind of silver lining, if we can imagine it, of the horror of the last year and a half is that once the hostages are our home, that there can be a healing process and a kind of social reconstruction that will take place as ripple effects of people coming together around the hostages, people of different political persuasions, people of different religious persuasions or denominational background. That could be a silver lining, and I see signs of it.

I do. But only time will tell.

Sruli Fruchter: What do the next steps look like for yourself and for your family at this period, at this point?

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Well, we can really only begin to mourn our losses and to begin to formulate what comes next only after all of our hostages are home. Those 14 who remain in Gaza, deceased or alive, our friends, our neighbors, kids who I helped grow, people that I worked with for decades, people that I argued with for decades, only when they come home to rejoin their families or for burial can the surviving community start really looking forward.

And that will only come actually after a full process of grieving for everything that’s been lost. Roughly half of the surviving community have already clearly stated that they do not want to go back to live on Nir Oz. The trauma is too great for themselves, for their children.

Nir Oz is a killing field. Every corner, every pathway, every home is a place where someone who we knew, perhaps loved, liked, was murdered, raped, burned alive, executed. And so for many of us, it’s just not an option to go back to live there. Another 25% of the surviving community, the older members who by and large don’t have children or certainly not little children who are living on the kibbutz, they would like to go back to a reconstructed Nir Oz.

That’s going to take quite a while. And then another 25% or so of the surviving community have decided to pretty much detach themselves from Nir Oz and are now pursuing lives elsewhere. They will not go back to Nir Oz and they’re not here with us and Kiryat Gat for all sorts of reasons. So it’s hard to say how things are going to roll out.

I don’t know what kind of decisions my kids are going to make about their futures. Certainly not the ones who survived, the two families who survived the massacre on Nir Oz. I imagine that will continue to be as tight, if not tighter, moving forward. But where that’s going to happen geographically right now, I honestly don’t have a clue.

Sruli Fruchter: All right. Well, Jonathan, thank you so much for your time. I’m so grateful that Sagui is back home with his family. Their family is reunited and I hope that by the time this is released or even earlier, all the hatufim are back and it’s irrelevant.

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: Thank you so much.

Sruli Fruchter: As the interview was going on, one of the things that I could not stop myself from thinking was just how surreal it was to be speaking to a father whose son, only a few weeks prior, was stuck in a tunnel in Gaza with Hamas terrorists, not knowing the fate of his wife, his children, his unborn daughter, his parents, his siblings, his kibbutz, all of Israel. As Jonathan mentioned repeatedly, all he remembered when he was leaving was seeing the bodies thrown about and all of Israel essentially in flames. And sitting across from Jonathan and being able to hear all of his perspectives, the personal, the political, the hopeful, was really extraordinary.

I was particularly really struck by his recollection of Sagui and his wife dreaming of the other in their sleep. I’m right now in the middle of this book by the philosopher Gaston Bachelard called The Poetics of Reverie, where he talks about the deep recesses of our spirits and our souls in the dream. And the fact that there was this mystical element, as Jonathan described, that allowed Sagui and his wife to hold one another close when everything separated them, geography, time, death, was really moving. I hope that this interview for you allows you to get greater insight into the experiences of the Dekel-Chen family and I hope that all the hostages return home to Israel very, very soon.

If there are others who you’d like us to interview, either hostage families or Israeli thinkers, please reach out to us at info@18Forty.org and please be sure to subscribe and join our free newsletter to get the latest podcasts, essays, and content from all things 18Forty. So until next time, thank you so much for listening.

This transcript was produced by Sofer.AI.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Chava Green: ‘From God’s perspective, men and women are exactly the same’

Dr. Chava Green joins us to discuss the role of women in the Messianic Era and seeing God in the everyday.

podcast

Chava Green: What Is Chabad’s Feminist Vision?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Chava Green—an emerging scholar who wrote her doctoral dissertation on “the Hasidic face of feminism”—about how the Lubavitcher Rebbe infused American sensibilities with mystical sensitivities, paying particular attention to the role of women.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

Eitan Webb and Ari Israel: What’s Next for Jewish Students in Secular College?

We speak with Rabbis Eitan Webb and Ari Israel about Jewish life on college campuses today.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Pawel Maciejko: Sabbateanism and the Roots of Secular Judaism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to historian and professor Pawel Maciejko about the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, Sabbateanism, and the roots of Jewish secularism.

podcast

Eitan Hersh: Can the Jewish Left Talk With the Jewish Right?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Eitan Hersh, a professor of political science at Tufts University, about teaching students of radically different political and religious views how to speak to one another.

podcast

Shais Taub: ‘God gave us an ego to protect us’

Rabbi Shais Taub discusses how mysticism can revive the Jewish People.

podcast

Liel Leibovitz and Lisa Ann Sandell: When A Spouse Finds Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Liel Leibovitz and Lisa Ann Sandell about what happens when one partner wants to increase their religious practice.

podcast

David Bashevkin: My Mental Health Journey

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin opens up about his mental health journey.

podcast

Mark Wildes: Is Modern Orthodox Outreach the Way Forward?

We speak with Mark Wildes, founder and director of Manhattan Jewish Experience, about Modern Orthodox outreach.

podcast

Bruce Feiler: The Stories That Bind Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to author Bruce Feiler about family narratives.

podcast

Ken Brodkin: A Shul Becomes Orthodox

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Ken Brodkin, rabbi of New Jersey’s Congregation B’nai Israel, about how he helped turn it into “the Orthodox synagogue for all Jews.”

podcast

Dovid Bashevkin: A Reform Rabbi Interviews an Orthodox Rabbi [Denominations 2/2]

David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko about denominations and Jewish Peoplehood.

podcast

Leah Forster: Of Comedy and Community

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David sits down with Leah Forster, a world-famous ex-Hasidic comedian, to talk about how her journey has affected her comedy.

podcast

Child & Parental Alienation: Keeping Families Together

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we discuss parental alienation.

podcast

How Different Jewish Communities Date

On this episode of 18Forty, we explore the world of Jewish dating.

podcast

The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

podcast

Larry and Tzipora Rothwachs: Here Without You — A Child’s Eating Disorder

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Larry Rothwachs and his daughter Tzipora about the relationship of a father and daughter through distance while battling an eating disorder.

podcast

Yossi Klein Halevi: ‘Anti-Zionism is an existential threat to the Jewish People’

Yossi answers 18 questions on Israel.

Recommended Articles

Essays

The Four Pillars That Actually Shape Jewish High School

These four forces are quietly determining what our schools prioritize—and what they neglect.

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

5 Ways the Torah Trains Us to Love Our Enemies

In Parshat Mishpatim, the Torah embeds one of its most radical emotional demands inside its civil code: Help your enemy.

Essays

Why So Many Laws? Mishpatim and the Making of a Moral Society

What Mishpatim teaches about human nature, moral fragility, and the structures a just society requires.

Essays

Towards the Derech: How Does a Reform Jew Return?

The “way” of myself and other formerly Reform Jews is unclear, but our desire for spiritual growth is sincere.

Essays

Why Is Meir Kahane Making a Comeback Among Orthodox Jews?

Israeli minister Itamar Ben-Gvir wears the mantle of Kahane in Israel. Many Orthodox Jews welcomed him with open arms.

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

How Archaeology Rewrote the History of Tefillin

From verses in Parshat Bo to desert caves, tefillin emerge as one of Judaism’s earliest embodied practices.

Essays

A Letter to Children Estranged From Their Parents

Children cannot truly avoid the consequences of estrangement. Their parents’ shadow will always follow.

Essays

How Rav Kook and the Lubavitcher Rebbe Saw the Jewish People

What if the deepest encounter with God is found not in texts, but in a people? Rav Kook and the Lubavitcher Rebbe…

Essays

Is Judaism Fundamentally Zionist?

God promised the Land of Israel to the Jewish People, so why are some rabbis anti-Zionists?

Essays

5 Perspectives on Sinai in an Age of Empiricism

Parshat Yitro anchors Judaism in revelation. But what does Sinai mean in a world where proof is the highest authority?

Essays

Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits’ Complicated Portrait of Faith

Meet a traditional rabbi in an untraditional time, willing to deal with faith in all its beauty—and hardships.

Essays

‘Don’t Wait as Long as I Did’: Seven Stories of Aliyah

A 94-year-old Holocaust survivor, a lone soldier, and more. Here are seven olim sharing their stories of aliyah.

Essays

The Siddur Has a Lot of Prayers. Where Did They Come From?

Between early prayer books, kabbalistic additions, and the printing press, the siddur we have today is filled with prayers from across history.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

What Are the Origins of the Oral Torah?

A bedrock principle of Orthodox Judaism is that we received not only the Written Torah at Sinai but also the oral one—does…

Essays

The Hardal Community Explained: Torah, Am Yisrael, and Redemption

Religious Zionism is a spectrum—and I would place my Hardal community on the right of that spectrum.

Essays

The Israeli Peace Activist and Religious Leader You Need to Know

Rav Froman was a complicated character in Israel and in his own home city of Tekoa, as people from both the right…

Essays

The Reform Movement Challenged the Oral Torah. How Did Orthodox Rabbis Respond?

Reform leaders argued that because of the rabbis’ strained and illogical interpretations in the Talmud, halachic Judaism had lost sight of God.…

Essays

A Letter to Parents of Intergenerational Divergees

Children don’t come with guarantees. Washing machines come with guarantees.

Essays

Rav Tzadok of Lublin on History and Halacha

Rav Tzadok held fascinating views on the history of rabbinic Judaism, but his writings are often cryptic and challenging to understand. Here’s…

Essays

Do You Have the Free Will to Read This?

The most important question in Jewish thought is whether we are truly “free” to decide anything.

Essays

What Haredim Can Teach Us About Getting Off Our Smartphones

Kosher phones make calls and send texts. No Instagram, no TikTok, and no distractions. Maybe it’s time the world embraces them.

Recommended Videos

videos

Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin: How Torah Gives Us Faith and Hope

In this special Simchas Torah episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin—parents of murdered hostage Hersh…

videos

The Hasidic Rebbe Who Left it All — And Then Returned

Why did this Hasidic Rebbe move from Poland to Israel, only to change his name, leave religion, and disappear to Los Angeles?

videos

A Reform Rabbi Interviews an Orthodox Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko (Part 2)

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue,…

videos

An Orthodox Rabbi Interviews a Reform Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue, about denominations…

videos

Joey Rosenfeld: What Does Jewish Mysticism Say About This Moment?

We speak with Joey Rosenfeld about how our generation can understand suffering.

videos

Is Modern Orthodox kiruv the way forward for American Jews? | Dovid Bashevkin & Mark Wildes

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Mark Wildes, founder and director of Manhattan Jewish Experience, about Modern Orthodox…

videos

Why Naftuli Moster Left Haredi Education Activism

We speak with Naftuli Moster about how and why he changed his understanding of the values imparted by Judaism.

videos

What’s Next for Jewish Students in Secular College?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rabbis Eitan Webb and Ari Israel, head of a campus Chabad and…

videos

What are Israel’s Greatest Success and Mistake in the Gaza War?

What has been Israel’s greatest success and greatest mistake?

videos

Mysticism

In a disenchanted world, we can turn to mysticism to find enchantment, to remember that there is something more under the surface…

videos

Jewish Peoplehood

What is Jewish peoplehood? In a world that is increasingly international in its scope, our appreciation for the national or the tribal…

videos

Sarah Yehudit Schneider: ‘Jewish mysticism is not so different from any mysticism’

Rabbanit Sarah Yehudit Schneider believes meditation is the entryway to understanding mysticism.

videos

Moshe Benovitz: Why Religious Change Doesn’t Always Last

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, recorded live at Stern College, we speak with Rabbi Moshe Benovitz, director of NCSY Kollel,…

videos

Zevi Slavin: ‘To be a mystic is to be human at its most raw’

As a Chabad Hasid, Rabbi Zevi Slavin’s formative years were spent immersed in the rich traditions of Chassidut and Kabbala.

videos

Suri Weingot: ‘The fellow Jew is as close to God as you’ll get’

What does it mean to experience God as lived reality?

videos

Matisyahu: Teshuva in the Spotlight

We talk to Matisyahu, who has publicly re-embraced his Judaism and Zionism.

videos

Is AI the New Printing Press?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast—recorded at the 18Forty X ASFoundation AI Summit—we speak with Moshe Koppel, Malka Simkovich, and Tikvah…

videos

Jonathan Rosenblum Answers 18 Questions on the Haredi Draft, Netanyahu, and a Religious State

Talking about the “Haredi community” is a misnomer, Jonathan Rosenblum says, and simplifies its diversity of thought and perspectives. A Yale-trained lawyer…