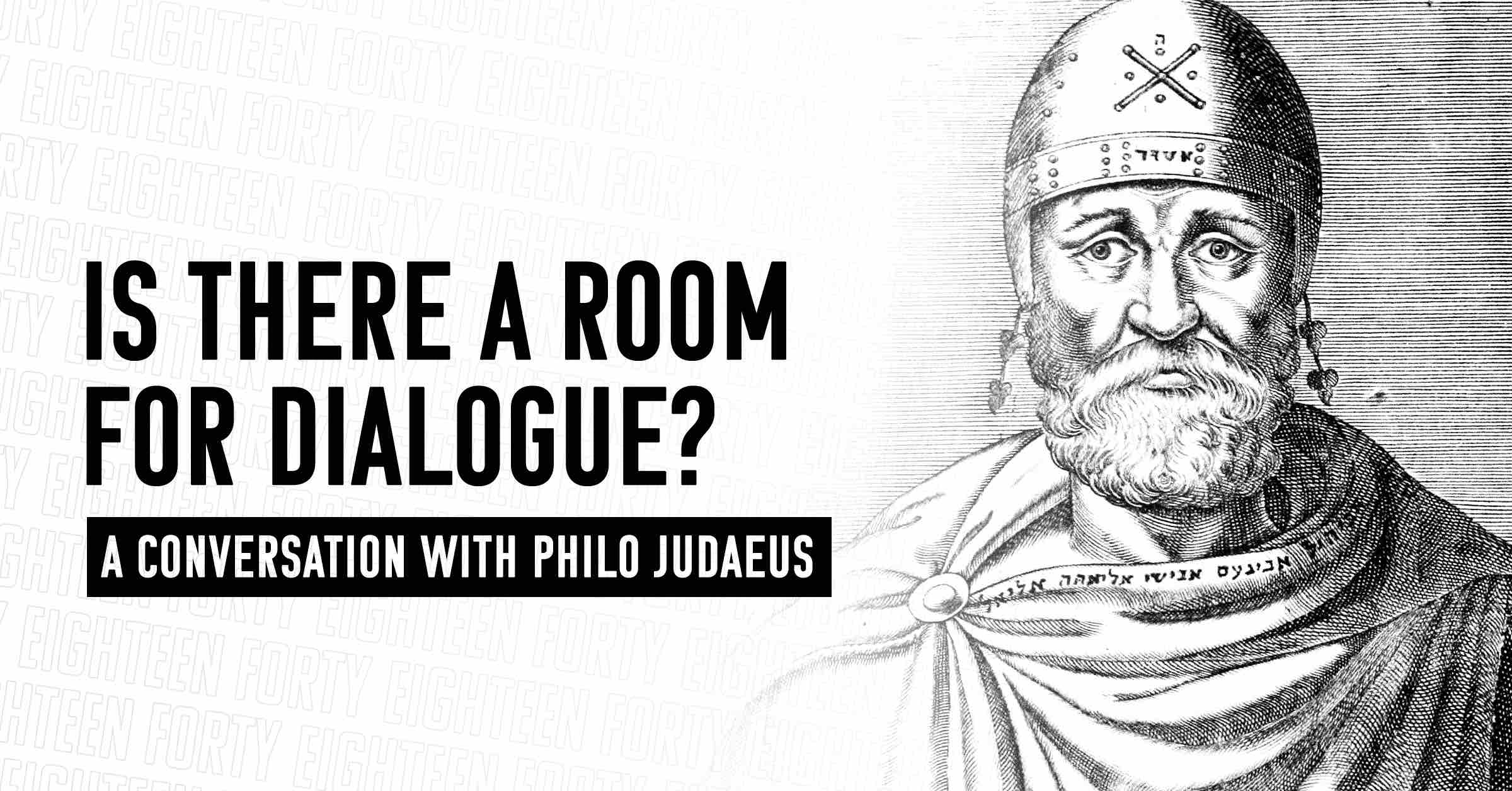

Philo Judaeus: Is There a Room for Dialogue

In this episode of the 18Forty podcast, David invites a man who goes by the pseudonym Philo Judaeus – former member of the Orthodox Jewish community and moderator of the ambitious Frum/OTD Dialogue Facebook group – to discuss the intersection of philosophy and religiosity.

Summary

In this episode of the 18Forty podcast, David invites a man who goes by the pseudonym Philo Judaeus – former member of the Orthodox Jewish community and moderator of the ambitious Frum/OTD Dialogue Facebook group – to discuss the intersection of philosophy and religiosity.

According to Philo, even most of the greatest atheistic cosmologists would concede that there are compelling arguments for the existence of a divine being, and yet these same scientists remain atheist. Our deep-rooted motivations behind religious commitment may often go unquestioned, and Philo suggests this as a worthy mental exercise.

- In our commitment to religious observance, or lack thereof, how prevalent are the elements of logic? Pragmatism? Blind faith?

- How deep into these philosophical rabbit-holes must we venture, as individuals, to achieve fulfilment?

Many times, it’s the way we resolve these philosophical questions that direct us one way or another.

Tune in to join David and Philo Judaeus as they explore how we can build understanding between the frum and OTD community, perhaps first by understanding ourselves.

David Bashevkin:

Welcome to the 18Forty Podcast, where we discuss issues, personalities and ideas about religion and traditional world confrontation with modernity, and how on earth are we supposed to construct meaning in the contemporary world right now. It is my distinct pleasure to invite an old friend, who are we going to introduce by his pseudonym, Philo Judaeus. He’s done incredible work online bridging the world of the OTD community, people who have left traditional observance, and the frum community, people who are still affiliated with the mainstream Orthodox community. Philo, it is such a pleasure to be with you today. Okay, I guess what I want to start with, because people who have followed your postings online, and it’s important to say that you’re… I don’t know, did you start the group on Facebook? There’s a group on Facebook called Frum/OTD Dialogue, which facilitates dialogue between people who have left the community and people who are still in it. Did you start that group actually?

Philo Judaeus:

I did not. That was Jechezkel Frank, who starts groups right and left. He started the main Off The Derech group, he started the Frum/OTD group, he started the Respectfully Debating Judaism group, he started several other groups –

David Bashevkin:

So he started a million groups. He’s one of those… He’s probably starting WhatsApp groups as we talk, adding people –

Philo Judaeus:

He’s awesome.

David Bashevkin:

I’m sure he’s great. I don’t know him personally, I do know you personally and you play a major role. You’re one of the moderators as am I, and the difference is, while we both had a yeshiva education, we both spent time together in a yeshiva, you have left traditional observance. I was wondering if to begin, you could share some of your story, what type of home did you grow up in, and at what point in your life did you start having religious doubts that eventually had you really, caused you to overturn your entire life, at a stage when so many other people just keep on going with what they have?

Philo Judaeus:

Okay, so I will try to keep this within the time limit.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, I’m definitely going to have to cut you off. I happen to know your story already, but give us that general overview.

Philo Judaeus:

Okay. So in terms of the family I grew up in, wonderful family. Absolutely wonderful family. My parents are amazing people, my siblings are amazing people, and I should say right off the bat that they still act around me completely normal. They have without any pause. I’m sure they’re in tremendous pain inside, but they joke around and they act normal, and we go over to their house and it’s amazing. My brother calls me every week.

David Bashevkin:

I love that.

Philo Judaeus:

Backstory very briefly, I went to a normal yeshiva. I’ll say which yeshiva because David sort of mentioned it, I went to Ner Yisrael in Baltimore…

David Bashevkin:

Mic drop, there it is, okay…

Philo Judaeus:

All right, sorry, now we’re going to have people trying to find my identity, but that’s okay… Wonderful yeshiva, I had a wonderful experience there, absolutely wonderful rebbeim, I had very close relationships with my rebbeim. I began having questions in, probably ninth grade. I don’t remember if it was ninth or tenth grade when I first read, Rabbi Natan, used to be Nosson Slifkin’s books. I remember reading Gerald Schroeder’s books, I think that was in tenth grade. By eleventh grade, when Rabbi Mechanic came to Ner Yisrael to present his kiruv…

David Bashevkin:

He ran this seminar, this Rabbi Mechanic, ran the discovery seminar when they would come in, and it’s so funny, he came to my high school too, and you and I had very similar experiences, where they would come in and would so to speak prove the existence of God and the authenticity of the Torah. He came to my high school and he came to yours. How did you react when he came to your school?

Philo Judaeus:

He actually asked for volunteer apikoros at one point, and I volunteered, and I presented something, it is related to the kuzari argument which I don’t want to go into, I have this general policy that I do not mention details of any arguments against Judaism, for or against really, online, which –

David Bashevkin:

I love that – It’s a fascinating policy and one I hope we talk about. I think in many ways it’s extremely admirable. It’s kind of like… We can go into it later, is it out of respect for your own past, for your family, or whatever it was, but you pushed back very hard on one of the proofs for the authenticity of the Torah.

Philo Judaeus:

Correct, and then I was, shall we say very unimpressed with his response. In general, I was very unimpressed, and I was left with the feeling of, “Is that it? That’s why we believe for these…” What seemed to me to be very flimsy arguments.

David Bashevkin:

Philo, it’s so interesting. I think I’ve shared this with you before. I’m not sure what grade it was for me. It was probably tenth grade, and they did the same, and there was something about couching it in proofs, and even though there are disclaimers, “We’re not really proving it, we’re a little bit proving it,” there was a little bit of an emptiness that I felt afterwards. It was deeply unsatisfying in many ways, and it’s important to highlight, maybe you could talk about this at this stage. When we were growing up, and we’re around the same age, the model, and the way we would think about people going off the derech, people leaving their faith, the model was always somebody who’s standing outside of the pizza store, they’re smoking a cigarette, they’ve got a cool haircut, they look like they’re out of the movie Grease, they’re John Travolta in Grease, a reference that you probably don’t even get, because you didn’t grow up watching movies, you grew up in a much more insular home than I did. Your journey was very different than that. Meaning you… When I was in yeshiva with you, you weren’t smoking cigarettes, you weren’t chilling and being a bad boy and watching DVDs, and you weren’t going out partying. You were very intellectually-driven, which I think makes your story, for a lot of people, a lot more frightening.

Philo Judaeus:

Okay, yeah, that’s probably true. I was usually considered one the masmidim.

David Bashevkin:

Masmidim meaning you were learning full-time, and I remember that. You were learning a lot of funky stuff too, let’s-

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah, I was doing some, I did a lot of hashkafa sefarim that were not on the usual beaten track. Then I remember I had this Friday night in the dining room. Sometimes I would pull out a physics book and over the cholent there was a group of guys who would discuss physics, fundamental physics and cosmology and how that had to do with hashkafa. So, yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Fascinating. So you had this knowing doubts since you had this discovery seminar. When did the-

Philo Judaeus:

I don’t think that Rabbi Mechanic triggered it. I know for other people, hearing these arguments is what sent them off the derech. I know somebody who, listening to… He was not an intellectual, really, didn’t think about any of these arguments for or against, and as an adult he, in a very shtark yeshiva, came across Rabbi Gottlieb’s shiurim, and he was so unimpressed with it that he went off the derech.

David Bashevkin:

Wow.

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah. For me, I strongly suspect that I would have questioned enough as it is, I think…

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, meaning, we’re not blaming anybody. Maybe it accelerated it, maybe it exacerbated existing – It was a preexisting condition, your curiosity, your intellectual curiosity. But when did it blossom into, when did it start having an effect on your ability to commit to your community, to the tradition you were raised with? When did that start?

Philo Judaeus:

So very briefly. So by second year beis medrash I didn’t feel like I had any reason to believe. I was pretty desperate, didn’t know what to do. I went to one of my rebbeim, and we had a very long conversation, and he came up with what’s known as Pascal’s wager –

David Bashevkin:

Did he know about Pascal’s wager?

Philo Judaeus:

He did, which was very impressive.

David Bashevkin:

Really?

Philo Judaeus:

He came up with it on his own.

David Bashevkin:

Wow. So, what’s Pascal’s wager?

Philo Judaeus:

So Pascal’s wager is: how much are you willing to bet? Okay, so the arguments seem flimsy. It seems like, probably there’s no God, probably the religion is false, or something like that, but if there’s –

David Bashevkin:

A chance –

Philo Judaeus:

If there’s a chance that it’s right, and on the chance that it’s right and God is going to send you to hell for not believing, and/or we’ll reward you with eternal bliss for believing, that’s huge. This can be formalized in probability theory. I should say that I have a degree in mathematics and I also –

David Bashevkin:

Well no spoilers where you are now, but we’ll definitely get to your current work in logic and mathematics, which is definitely, that’s that inner personality that you have, it’s more than just your profession, it’s a personality.

Philo Judaeus:

So anyway, Pascal’s wager has some very obvious flaws, the most obvious of which is, okay, maybe that says to believe, but which religion? Because they’re all mutually exclusive, and if you believe in the Christian God, the Jewish God is going to send you to hell and vice versa. But for that, I figured that to choose between religion, so Pascal’s wager I figured is enough to –

David Bashevkin:

It was a band aid that helped you get a little bit farther saying, “Look, I’m not 100% sure, and on the losing side of the bet, you lose everything in the world to come. So why not go along with the bet,” even though the logic of the bet doesn’t really extend to Orthodox Judaism that you had, but that you were able to justify with a little bit of logic saying, “maybe your sense of confidence in the tradition that you were raised was enough to keep you in that path, as well.”

Philo Judaeus:

No, for that I was actually relying on the kiruv arguments. I said –

David Bashevkin:

Oh, okay, that’ll keep you over.

Philo Judaeus:

At the time I thought that those were enough to tip it over in favor of Judaism. There were arguments that people discuss that argue for Orthodox Judaism. So I thought that was enough.

David Bashevkin:

Okay.

Philo Judaeus:

So that actually kept me frum and very happily frum, for 10 years.

David Bashevkin:

And in that time you got married and you had children.

Philo Judaeus:

I got married, I had kids. I was in kollel, shteiging away… But Pascal’s wager is not a very –

David Bashevkin:

It’s hard to build a life around the wager.

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah, I did it, because I thought it was very compelling, but it’s not a very satisfying reason to believe. So it always bothered me, especially around Rosh Hashanah Yom Kippur, because then you’re really focused on your spiritual life. So I always resolved to get to the bottom of it, and I always looked into it more and more. I could never convince myself from the arguments that I was researching, but I always fell back on Pascal’s wager. Then after about 10 years of that, I realized that the only argument that I had not looked into was Pascal’s wager itself, because I was terrified that if I looked into Pascal’s wager, it would fall apart, and then my life would be –

David Bashevkin:

What would you be left with? Meaning, if you poked a hole in the wager and the logic holding up the wager itself, it’s like that famous Chinese metaphor, when they said, “What’s holding up the world?” And they said, “It’s on the back of a turtle.” They said, “Well, what’s turtle standing on?” They said, “It turtles the whole way down.” It’s scary, if your life’s standing on a wager, what’s the logic of the wager standing on? You have to take another Pascal’s wager to keep the wager going. It’s challenging –

Philo Judaeus:

I actually wrote… To skip ahead, I did mention that I have a degree in philosophy, but I once wrote a paper – senior-level for a course in decision theory, philosophical decision theory – I wrote a paper on, my final paper for the semester was on a Pascal’s wager, and I actually think it’s a pretty good argument, it’s very hard to get out of, if you think about it. I think it does fail, but I think it does not fail for the reasons that most people think it fails.

David Bashevkin:

It’s stronger than a lot of people will give him credit for, you don’t dismiss it so quickly.

Philo Judaeus:

Yes. If anybody is interested, you can contact David and he will… Or you can contact me online, I’m on Facebook, and I’m happy to send you that essay. Incidentally, I should say that this entire background story, and I have it written up online, it’s on offthederech.org –

David Bashevkin:

I could send out this stuff, I could send out all this stuff. I have a written part, I’ll have all your writings over there, and they can see your ideas without a doubt. So at this point you’re married, you have children, and the wager starts to deteriorate for you.

Philo Judaeus:

So yeah, it was pretty quick. I realized that was circular, so I looked into it, and I took out several academic books from the local university library, and it fell apart, that was it.

David Bashevkin:

So what were you left with at that point? You’re married, you have a family, you’re in kollel, I mean, what next? Do you get a job? What happens the next morning? Even in your personal health, your emotional health, how are you holding up at that point?

Philo Judaeus:

So I actually, when it fell apart, I decided to brute force, just use mental…

David Bashevkin:

Force of will, keep it going.

Philo Judaeus:

I bisected my mind. In one half of my mind, I didn’t think there was any reason to believe. The other half, I just forced myself to believe anyway. That went on for a couple of months, it was mental torture, it was hell, it was really bad. It didn’t always work, it’s very hard to maintain.

David Bashevkin:

During that period, were there parts of religious affiliation that still gave you meaning and comfort, meaning, the core belief for you had eroded, but for so many people, and this we’ve discussed before, the source of their affiliation is not any sort of intellectual tower, not in their religious life, and for most people, it’s not in any aspect of their life. I think the uniqueness that you have is you have this soul of a logician, so you really want to make sure that you’re always on firm grounding for your decision, whether that’s a decision to get married, whether that’s a decision of your religious affiliation, or what career to go in. But I’m curious, for you… For most people, aren’t those decisions – what career to go into, who to marry – it’s not built on any rigorous logical foundation. So why do you think for you it was so difficult? Do you think you’re unique in that aspect?

Philo Judaeus:

Definitely not unique, I know plenty of people like that. I would say that it seems to me, anecdotally, a little more common among the Yeshiva world, because, for some reason, the Yeshiva World has taken the position… This goes back to lots of sources and Reb Elchanan has things on this, and the Chazon Ish, they’ve taken the position that Orthodox Judaism and Judaism in general is demonstrably true, and that it should be completely obvious to any sane person who has experienced Judaism and looked at it that it’s just obviously true. Especially it’s completely, obviously true to anybody that God exists. When you’re raised, like I was, that we believe in the religion because it’s demonstrably true. So that’s how I was raised, especially…

David Bashevkin:

That’s so funny. I think it’s because we grew up in different homes, I’m loathe to insert any sort of psychoanalysis in this, but for me, my relationship with Judaism and with Yiddishkeit is so much more comparable to my relationship with a parent and a spouse, where the logical foundation is much more experiential, is much more visceral, which again, doesn’t necessarily hold up to true and false dichotomies, it’s an approach to my life that I certainly believe in, maybe there are aspects of it that I believe in so differently, but I don’t have the same logical framework that you grew up with in that way.

Philo Judaeus:

I know plenty… I think it’s more common in the more Modern Orthodox communities to be raised with, essentially emunah pshutah.

David Bashevkin:

Like a simple faith, that’s what I grew up with…

Philo Judaeus:

And in the more chassidish communities I think that’s more common also. That’s why I was saying that –

David Bashevkin:

In the Yeshiva community, it’s so obvious –

Philo Judaeus:

It’s not just so obvious… They go around with Rabbi Mechanic giving talks on this, and there’s so many books published on this, where people are raised – not everybody – but lots of people are raised in their Yeshiva, if not in their home, that we believe in the religion – that at least it’s implicitly imparted to the talmidim – that we believe in the religion because it’s demonstrably true. So for anybody who’s intellectual enough and curious –

David Bashevkin:

To question that and to really examine that, you could be left with a lot of dissatisfaction.

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah. On the other hand, I will say, I know you wanted to discuss this briefly, I do think that there are several approaches that, from a philosophy point of view, are defensible…

David Bashevkin:

That work. Let me phrase it this way: if you were going – again I know you said you weren’t triggered, I certainly don’t want to trigger you with the way I’m phrasing this question – If you, Philo, were going out now, and were going to re-imagine what the discovery seminar should be, and knowing everything that you’ve seen in all of the arguments, a Yeshiva hires you, Bashevkin, I hire you and say, “I know you’ve looked at both sides of this to the ends of the earth. You came to your decision, but knowing everything you know, we want to give a stronger foundation to our students. Forget about, not forget about forever, but not necessarily for Orthodox Judaism, help people believe in God.” What is the direction, and how would you frame that argument?

Philo Judaeus:

I think this is the point where I should explain what I said earlier, that I have this policy not to discuss arguments. I will discuss this, but I think it’s relevant. In general, I have no complaints about Orthodoxy, at least none beyond what plenty of Orthodox people complain –

David Bashevkin:

Yeah… I get it, exactly.

Philo Judaeus:

The same internal complaints –

David Bashevkin:

Frustrations that you have growing up in a community.

Philo Judaeus:

But outside of that, I think the Orthodox community is an absolutely wonderful community, and for many people, I think it is the right community to be in. Especially I have seen way too many people, their lives overturned. We’re going to have to get back to it, because I didn’t explain what happened.

David Bashevkin:

No, we’ll come back, this is an important point, I want to discuss this with you now, because this is the way you headed it. Continue, you’ve seen a lot of people overturned because they had doubts and they said, “I have doubts, so I should probably leave.”

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah, and then they lose their marriages, they sometimes lose their kids, it’s pretty bad. I have absolutely no interest in even indirectly causing anybody to lose their faith. In fact, I’m probably the primary moderator for the Frum/OTD dialogue group, I can probably –

David Bashevkin:

I respond to about like two percent of the questions, so it’s definitely not me, it’s probably you, yes.

Philo Judaeus:

So people know my story, and I regularly get people messaging me, “Oh no, what do I do? I have doubts, this is eating me up.”

David Bashevkin:

And let’s be Frank. You have had people come to you, and you’ve sent them and they’ve come to my office, and we’ve had conversations.

Philo Judaeus:

So I actively send them to… So it depends on the person. I’ll find out about where they’re holding, where’s their doubts, what are their doubts, what are their thoughts? I just find out about their life a little bit more, especially does their wife know? That’s a critical part. Where are they in their research?

David Bashevkin:

Is it usually men or women who come with these doubts?

Philo Judaeus:

To me, it’s men, but that’s probably just because I’m male.

David Bashevkin:

Okay. That’s fair.

Philo Judaeus:

But it’s not only men, I’ve been contacted by women too. So, their spouse, does their spouse know? For many people, I encourage them very strongly to try – the first thing to do is try to make it work… The first thing I’ll usually do is send them to various rabbis, including Rabbi David Bashevkin –

David Bashevkin:

Oh please, you’re being –

Philo Judaeus:

I, depending on, some people I’ll send to some rabbis, some people I’ll send to other rabbis, it depends which community did they come from and where they’re holding. I’ll send them to various rabbis to try it, who I think can help them figure out a path –

David Bashevkin:

To make it work.

Philo Judaeus:

Which they could use to believe. Sometimes I will actively try to convince them myself. I will not discuss with them arguments against, I will present the arguments for, in an effort to help them find a path. Sometimes that’s not enough…

David Bashevkin:

Just pause for a second. What’s the logic? We brought this up when we first started. Why won’t you argue against?

Philo Judaeus:

Because, a, I think that while for me truth is a paramount value and overrides a lot of… I’m willing to sacrifice some well-being to pursue what I view as the truth. For a lot of other people, that’s not the value system, and they’re more interested in, and I think justifiably so –

David Bashevkin:

Should be more interested, meaning that value doesn’t work for everybody –

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

To have a logical truth driving –

Philo Judaeus:

Absolutely. And if you’re looking for a community, it’s hard to do better, in many ways, than the frum community. I will actively encourage people to stay. I’ve had people, one person publicly on the Frum/OTD group, thanked me for keeping him frum.

David Bashevkin:

Look at you, running your own online discovery seminar, who would have thought?

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah, I actually have a coworker, who I work with all the time, very closely with, who, he was thinking of becoming frum. So I’m of the opinion that that’s a great thing to do, so long as you know what you’re getting into. So for ba’alei teshuvah it’s not always so straightforward as many –

David Bashevkin:

It could be tricky, that’s a tricky transition for sure.

Philo Judaeus:

But as long as he knows what he’s getting into, and he’s an intellectual guy, so we actually went through all the arguments for and against that he wanted to discuss. But I said, “As long as you know what you’re getting into, and if you think I’m wrong or if you think, or if you go with other approaches that it doesn’t make a difference if I’m wrong, which one’s actually correct, then go for it.” Then he just told me that he got his first pair of tefillin.

David Bashevkin:

Wow. That’s a beautiful story. But let’s return to that question where we got off on this sidetrack. The question that I wanted to know is imagine your… What do you feel is the strongest chain of, whether you want to call it logic or ideas, to help somebody really be convinced of the idea of God? They’re having doubts, they look around in the world, they’re reading about science and cosmology, it doesn’t seem to add up for them. What is your approach to the existence of God?

Philo Judaeus:

So I will say that I’m… Disclaimer, I’m –

David Bashevkin:

I don’t mean what do you believe in, I think that already we’ve implicitly understood –

Philo Judaeus:

I’m not exactly atheist, I’m agnostic leaning atheist, let’s say it like that. It’s more nuanced than that, but let’s say it like that.

David Bashevkin:

Sure. But what would you say to somebody who says, “I want to believe. Help me do, walk me through this.”

Philo Judaeus:

Okay, so there’s a couple of different approaches to this. I have a document that I share with people and I’m happy to share that goes into a little more detail about this. I usually say it like this: philosophy is amazing at showing us that just about everything that we believe is ultimately not justifiable in many different senses. So I can show you this almost a dozen different ways, but just as an easy one. So this is called Agrippa’s trilemma. So take any beliefs that you have and ask, what is that? What is the justification for that belief? So it’s a set of other beliefs. So what is the justification for each one of those beliefs? I keep going backwards. You can immediately see that you’re going to end in one of three places. You’re either going to end up with an infinite regress, where you just keep going back and keep going back and keep going back infinitely. That doesn’t sound very plausible to most people, although I have heard that there are some…

David Bashevkin:

If there’s ever somebody who gets stuck in an infinite regress, you probably know them and may even be friendly with them.

Philo Judaeus:

For every philosophical position, there is some philosopher out there who will defend it if only because they need something to defend in their PhD thesis.

David Bashevkin:

Correct.

Philo Judaeus:

But almost no philosophers go with the infinite regress version, so that leads to other possibilities. Either you’re going to end up with a set of beliefs that are just not justifiable, and you have to take them as is, it’s called foundationalism. There’s a set of foundational beliefs that just have no justification. You just have to take them, quote unquote, on faith. The other possibility is that it’s going to end up being circular, that ultimately you’re going to have some beliefs that will justify other beliefs that will justify by other beliefs that eventually will justify the first beliefs. In which case you basically just have a set of beliefs that’s foundational. It’s not just one belief that’s foundational, it’s the set of beliefs that’s foundational. So ultimately… And then there’s lots of other ways to show –

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, I know you have a hard time talking about this, cause your brain is always thinking about the other permutations –

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Simplify it for us.

Philo Judaeus:

Humes riddle of induction, there’s a long list of these. Philosophy is fantastic at showing you, this is like intro to philosophy courses where the professor has so much fun messing up the students’ minds, just blowing their minds by showing them, “Hey, everything that you took for granted, your beliefs actually are justifiable, actually not really.”

David Bashevkin:

So once all of your beliefs are not necessarily justifiable, what’s the next step?

Philo Judaeus:

Okay, next step. There’s several ways to proceed from there. Number one, my personal inclination is always to go with the… So the question is, so where do you start, right? What’s the foundational set of beliefs that you’re going to start with? So my inclination, if you asked me, would be to say, “Okay, it’s the bare minimum that we need to get things off the ground, something like,” I’m not going to go into details about that, something like the scientific method or… Maybe, the outside worlds exist, or something like that.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Philo Judaeus:

But I actually found out to my surprise and in my philosophy department that most philosophers, traditional philosophers, analytic philosophers, do not have that approach, although a very significant, a very sizable percentage of them do. They have some similar approaches, but a lot of philosophers actually go with the approach that they start with the assumption that all their strong seeming intuitions that seem very foundational to them, you just start with the assumption that they’re all correct. Then sort of naively a priori assume that they’re correct, then philosophy mainly consists of bashing these intuitions against each other and seeing which ones we have to jettison or modify. Whereas I would start with like the minimum set and build up, most philosophers actually start with a much larger set and tear it down. From that perspective actually it turns out that a lot of the more traditional arguments for God, actually have a lot more strength to them. Most traditional philosophers are atheists or lean atheist, but a significant percentage don’t –

David Bashevkin:

Which of the approaches for the belief in God do you find most satisfying?

Philo Judaeus:

So the most compelling set of actual arguments, even from my perspective, if I was going to argue for God, from a logical perspective, the way I would do it is a combination of what’s called… You’re going to forgive me, I’m not going to go into all the details of all of these, because you don’t have time.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, but use the names and then you’ll explain it simply.

Philo Judaeus:

Okay.

David Bashevkin:

It’s a combination of –

Philo Judaeus:

The hard problem of consciousness, David Chalmers –

David Bashevkin:

I love him, you speak my language.

Philo Judaeus:

So, in very brief, this is really hard to actually convey, I’ve found. There is something that, it seems to almost everybody that there is something it is like –

David Bashevkin:

There’s a quality to being conscious that’s nearly indescribable, but everybody is aware of.

Philo Judaeus:

It’s the experience of seeing green, not the knowledge, the information content, but the –

David Bashevkin:

Correct, the experience, exactly, of wakefulness and being alive and consciousness. So what is the hard problem of consciousness that –

Philo Judaeus:

David Chalmers, famous philosopher of mind, he distinguished between the easy problem and the hard problem. Now, the easy problems are not very easy, but they consist of things like, how are we aware in a… Forget about the experience part, but how do we know about our own, what we’re sensing? So, self-awareness, right? That seems to be a matter of finding the right places in the brain…

David Bashevkin:

It’s a biological question.

Philo Judaeus:

It’s a physiological, neurological –

David Bashevkin:

Exactly.

Philo Judaeus:

Cognitive science question. It’s easy in the sense that we expect to be able to solve it one day.

David Bashevkin:

To identify, this is the spot where your feeling of sadness comes from, or the experience or –

Philo Judaeus:

Not the experience –

David Bashevkin:

The feelings, so to speak.

Philo Judaeus:

The emotion, the physiological response to different emotions comes from the higher level, that one part of the brain knows about what the other part of the brain is thinking –

David Bashevkin:

Correct, but what’s the hard problem then? Because, that’s the easy one then. Yeah.

Philo Judaeus:

Right, so the hard problem is the experiential part, which a lot of people feel is just… There is absolutely no way that that could even theoretically be physical.

David Bashevkin:

Meaning at some point, physical mass had to evolve to the point where they were able to have experiences of being alive, what we experience every day in our consciousness. How that came to be, why that came to be, is the hard problem of consciousness.

Philo Judaeus:

No.

David Bashevkin:

No?

Philo Judaeus:

Not why –

David Bashevkin:

Not why?

Philo Judaeus:

Not how it evolved, but how it is possible at all.

David Bashevkin:

Correct. Even larger. Yes.

Philo Judaeus:

How is it possible at all for a physical being to have, what seems to us to be, a completely non-physical experience? So this is really hard to describe and I’ll give –

David Bashevkin:

He has a separate article called the meta problem, the hard problem of consciousness.

Philo Judaeus:

Yes… one of my favorite recent articles in philosophy –

David Bashevkin:

This rabbit hole goes deeper and deeper. We’re not going to get into all of that, but let’s start with the hard problem of consciousness.

Philo Judaeus:

Okay. Can you put some links, I’ll give you some links that you can put in the –

David Bashevkin:

Oh, absolutely. All the links are going to be online for this stuff.

Philo Judaeus:

Okay.

David Bashevkin:

So with you, with the hard problem of consciousness.

Philo Judaeus:

Then there’s another argument – So I think the hard problem of consciousness… Well, I don’t find it completely compelling. I find it pretty compelling. I think –

David Bashevkin:

Well, you’re missing one step, what is the – meaning, there’s something unexplainable about consciousness that requires something else that haven’t been provided.

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah. So I think one of the, for various reasons, especially this meta problem of consciousness that we’re not going to go into, but for more detailed reasons, I think that one of the best responses to the hard problem of consciousness is actually what’s called, in philosophy terms is called substance dualism, but it’s more colloquially known as a soul. Does this soul… Substance dualism is that there’s something, some sort of non-physical substance –

David Bashevkin:

That’s animating the world, so to speak.

Philo Judaeus:

That’s animating the physical brain.

David Bashevkin:

Correct.

Philo Judaeus:

That’s the non-physical correlate of what’s going on in your brain. So it’s plausible that… So it does not follow directly, and there’s actually arguments against this, that a lot of philosophers find very compelling. There are very few substance dualists out there.

David Bashevkin:

There are.

Philo Judaeus:

But there are… Yeah I think there should be more actually, I think it’s more compelling than most people give it credit for it. But I think it’s plausible that you can imagine such a, let’s call it a soul, surviving death. Most philosophers, even substance dualists, don’t think it would survive death… Meaning it’s intimately tied to the physical brain, but you could imagine such a thing surviving death, and you can also imagine by completely non-physical consciousness that is not attached to the physical at all. So that’s a background. Then I would point to more traditional arguments for God, I’m just going to rattle some off. The cosmological argument in the various forms, there’s all sorts of forms of that. But one of the most compelling I find is the cosmic fine-tuning argument, which uses cosmology and physics to argue that our universe is fine-tuned for… Forget about life, but it’s fine-tuned for anything beyond elementary particles floating in the void.

David Bashevkin:

The fact that it’s so fine-tuned, if one minor discrepancy in the laws of physics were changed, we have nothing.

Philo Judaeus:

Right. The universe wouldn’t have, the big bang would have just immediately collapsed on itself, or it would be elementary particles floating in the void or something. There’s quite a number of, apparently… There’s a lot of fundamental constants in cosmology and physics that scientists have no idea why they are at that constant and not any other constant –

David Bashevkin:

And literally, not just life, but the universe depends on that constant too –

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah, absolutely precise, it could be off by a factor of, some of them could be off by a factor of one in a billion, but I don’t actually remember all the details, but there are books on this, and we can link to some of them. But that is, even most atheistic cosmologists, or a lot of them anyway, concede that that is, at least on the surface, a pretty compelling argument.

David Bashevkin:

It’s definitely intriguing, meaning it’s fascinating. I remember, I have a book and it’s a question that Stephen Colbert asked Ricky Gervais when they were discussing religion. I find Steven Colbert’s faith very inspiring as I think I’ve spoken about in other contexts. There’s a book, it’s not as sophisticated, it’s called Why is there Something Rather Than Nothing? Which is a very crude way, it’s not the cosmological argument that you’re articulating necessarily –

Philo Judaeus:

So this is actually called the cosmic fine-tuning argument, and it’s distinct from the cosmological argument.

David Bashevkin:

Correct. So the cosmic fine-tuning is about the details of the constants and how all of physics is working together to have a universe. Something almost predates that, which is, why is there something rather than nothing? It’s like the most –

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah, that’s the cosmological argument.

David Bashevkin:

Correct. Okay, so with those two together, that to you, between the hard problem of consciousness and cosmological fine-tuning, which maybe, is that a subset of the cosmological argument or they’re just totally separate?

Philo Judaeus:

I think it’s usually considered separate.

David Bashevkin:

Okay. But those two together, you find that’s a, dare I say a compelling path for one who wants to commit to the existence of God of this world.

Philo Judaeus:

I would even go further than that and I would say that for at least some people, even if you don’t want to commit, but that’s just a completely logical…

David Bashevkin:

It might be your best option.

Philo Judaeus:

It might be the correct option. I personally don’t find that compelling enough, but I think, so let me just specify, let me just explain a little bit, I think that the hard problem of consciousness can get you to the point of saying, it’s at least plausible for there to be… Okay, let me start it the other way, actually. So the cosmic fine-tuning argument and the more traditional cosmological argument get you to: something really fishy is going on, possibly an intelligence designing this. And the cosmological argument doesn’t usually get you to an intelligence, the traditional cosmological argument doesn’t usually get you to an intelligence, it gets you to: there’s something non-physical that’s creating or giving life to the world, but we don’t know the details too much. The cosmic fine-tuning if it succeeds would point more directly at some sort of intelligence. I think the hard problem of consciousness gives a plausible, makes it plausible that a non-physical consciousness could be that thing that is giving, possibly intelligent thing, that is giving life to the universe. So I think the combination of those, it doesn’t… To some people that might be enough on its own, to other people that might be enough to push it over the hump to make it plausible enough to go with. So –

David Bashevkin:

Or it might quiet some of the doubts for –

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah. Let me just go all the way back to when we were discussing, yeah, so again, philosophy is really great at showing that your…

David Bashevkin:

Your beliefs are not what –

Philo Judaeus:

Ultimately not justifiable. So the question is where to start? So some people will start, as I described some of the more traditional analytic philosophers, will go with their more intuitions. And from that perspective, I think some of the more traditional arguments, possibly even some of the other traditional arguments for God, are significantly more compelling. But beyond that, a lot of people go with the approach that: look, you can’t prove this stuff, so ultimately, you have to go with pragmatism, which means that you believe – there’s various different types of pragmatism, but in a basic sense – you believe something because it is pragmatic to do so. So in a certain sense, I believe that I’m not going to fall off a cliff tomorrow –

David Bashevkin:

Because it allows you to function in this world.

Philo Judaeus:

Because it allows me to function, and for almost no other reason. I have to believe that, sorry, I have to believe that if I walk off the cliff, I’m going to get hurt or die, and therefore I won’t walk off a cliff, even though I might not be able to prove that. But I can’t function in the world otherwise.

David Bashevkin:

I think for a lot of people that’s the role of Jewish community, their affiliation serves as a certain pragmatism.

Philo Judaeus:

Yes. So a lot of philosophers will go with a very basic form of pragmatism, like: I’m not going to walk off the cliff. But there’s an extension of that which is frequently associated with the philosopher and psychologist William James: American pragmatism. That’s more traditional, that goes straight to religion. That is, look, it’s pragmatically useful, very useful, potentially, it’s debated how useful, but at least for many people, it is very useful.

David Bashevkin:

Philo, I get such a kick out of your struggle to get out a clear concise sentence because you’ve digested so much philosophical information –

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah. I apologize for not being clear.

David Bashevkin:

You speak in footnotes. I love it.

Philo Judaeus:

We’re going around a little bit.

David Bashevkin:

No, this is great. Finish this thought on pragmatism, because I think it’s very important, and for a lot of people, certainly for myself, there’s an element of pragmatism, not just in my religious life, in all of my life, the way I make decisions.

Philo Judaeus:

A lot of will go with the approach that, look, religion, possibly Orthodox Judaism, is very pragmatically useful for me, for my life, and I’m just going to go with that. Some people… For many people that becomes a question of, okay, how implausible does it have to be –

David Bashevkin:

To lose it’s pragmatism.

Philo Judaeus:

To say that… So William James referred to it as, they have to, both sides have to be, what he called live options. I think that was his phrase. So what exactly is a live option is up to people’s discretion. But a lot of people, so people have different thresholds for it, but then you could use… So for a lot of people, you can use various arguments for God and that’s enough. Then you could use various arguments for religion and you can use –

David Bashevkin:

Pragmatism.

Philo Judaeus:

Answers for all the questions that there’s lots of these books, for different approaches. There’s different, really good books for every level of… Whatever level of orthodoxy you want to go with, there’s a book that’s trying to defend it, and if you find that compelling enough to go over your threshold, then that’s fine, you can just go with it. A lot of people do this. And I’m completely sympathetic to it, it’s simply that my mind does not work that way.

David Bashevkin:

That has definitely transmitted, and that’s fine. I’ve always said that the difference between you and me is the fundamental heuristics, the fundamental processes we use to construct meaning in the world, that’s what we spoke about earlier. I think that you begin with a very logical sequential progression in the way you make decisions in your life, and I definitely don’t operate that way. I don’t think most people do. I’m not saying nobody does, I don’t think you’re unique, the only person who does that, but it’s definitely a difference between you and I in this category. I think that the way that people, the way that you approach or different people approach religion very often correlates to the way that they approach other areas of their life. There’s a heuristic, there’s an approach and a methodology for how people need to determine to construct meaning in their life, and It’s important to find a way and a methodology that works for you, and that is going to build a meaningful life for you.

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah. So I happen to find, and a lot of people happen to find, that I have a perfectly meaningful life.

David Bashevkin:

Oh, God forbid, I wasn’t saying that your life’s not meaningful.

Philo Judaeus:

No, I understand exactly what you’re saying, but a lot of people actually don’t find meaning, they find this gaping hole, if they would, possibly a terrifyingly gaping hole, if they would stop believing.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, in the book Jew versus Jew, Samuel Freedman quotes somebody who says, when they left their community, it felt like a tear was formed in their ozone layer of meaning in their life, and rays of meaninglessness started to beat down on them. That’s an experience I’ve had in my life.

Philo Judaeus:

So I will, I can also send you, you’re going to have to kind of remind me of all the things I’m telling you to send –

David Bashevkin:

Well, the good thing is I already have most of your stuff, but –

Philo Judaeus:

I can send you a… Actually this one you don’t have. Although I posted it recently on the Frum/OTD group… I put together a list of some resources for finding meaning from a secular perspective.

David Bashevkin:

I bought a ton of those books. I found them very intriguing and a lot of them very helpful. I want to switch to our final topic, if time permits and really talk about the dialogue that you fostered in this group, and I want to ask just a very basic –

Philo Judaeus:

Can I just mention one thing that I said we should get back to, and that is my life since the loss of faith. I will just mention that, so what happened since then is that, so after a couple of months of brute-forcing myself to believe, I gave that up and then… But then I was getting it from my wife, which was also torture for me, because I have a wonderful relationship with my wife. Eventually I told her I’m not going to get into the, the way I told her was a, it was a… I broke it to her very slowly, let’s say. But I did tell her for a couple of years after that –

David Bashevkin:

And you had children at this point, which is what really complicated and made it especially painful.

Philo Judaeus:

So, for a couple years after that… My wife, fully religious and she asked me to keep everything, even in private. So I did, I kept everything, it didn’t really bother me that much, I like religion. So, I kept everything in private. The only two things I didn’t do were davening and learning because that was emotionally too painful for me, because of the loss of faith.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Philo Judaeus:

It’s just two –

David Bashevkin:

That’s very moving. It’s moving imagery to think about having built a relationship and spent so long with davening and learning, to return back to it, absent of the faith that used to animate it, could be especially painful.

Philo Judaeus:

Right. But other than that I kept everything in private for years. Eventually my wife started saying, “Okay, you could do this, a little bit in private.” Fine. Very gradually, she started losing her faith also. It was a process over a couple of years, but eventually, she’s on the same page as me now. We realized… Then it actually became very hard for her. While for me it’s very easy to live as an Orthodox Jew, even if I don’t believe it, I have my outlets, I communicated with lots of people like me online, so that was great. But I didn’t need very many outlets. But my wife, she’s a very straightforward, authentic person, and she could not handle the duplicity of living a double life. It was really, really impacting her psychologically and emotionally, and we decided we couldn’t continue it. Eventually the kids are going to figure this out, and then it might not be so good. So we… This is kind of funny from people who know me, we executed a very carefully planned out six month transition, which went reasonably well, I mean, we’re still in very close contact with all my relatives, or almost all my other relatives anyway. We have a good relationship with almost all of them. And… I wrote that letter –

David Bashevkin:

And you essentially left the Orthodox community, where you are now.

Philo Judaeus:

We slipped out of the community that we were in, in a way that we didn’t announce that we were going. But now we don’t, we live in a different town outside the community, we’re very happy here. My kids go to public school, they transitioned wonderfully, no problems whatsoever.

David Bashevkin:

So let me ask you now, coming to this dialogue question. You began a group, you didn’t begin the group, but you now moderate a group, which I also facilitate on called Frum/OTD dialogue. I want to begin with two very basic questions, doesn’t need a long philosophical answer, but: What do you think the frum community should be learning from the OTD community, and what do you think the OTD community should be learning from the Frum community?

Philo Judaeus:

So the purpose of the group is essentially to build bridges between the frum community, frum people and OTD people, to build understanding, not necessarily that we’re going to reach each other, and you can still disagree very strongly with people, but accept them as wonderful people, and respect them as good people. By meeting people online who are from the opposite group in the frum OTD divide. So it works both ways. The frum people often have very strong misconceptions about OTD people. As you alluded to, there’s this… We grew up with the stereotype of someone who goes off the derech. There’s also –

David Bashevkin:

They do it for their lust, and they want to party and gamble and do this.

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah, people –

David Bashevkin:

And that’s not why everybody leaves. Some people leave, I would almost describe as… I don’t want to say legitimate reasons, but yeah, they leave because they were not able to wrap their heads around their faith. It did not work for them.

Philo Judaeus:

Or they leave for lots of other reasons, like, it really honestly doesn’t work for them. Some people leave because of perceived hypocrisy or misogyny and racism –

David Bashevkin:

The list goes on.

Philo Judaeus:

It goes on and on, and I will also point out that, while we’ve been talking about people leaving from intellectual point of view, I think it’s perfectly legitimate to leave for emotional reasons as well. People become frum for emotional reasons, that’s –

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Philo Judaeus:

Commonplace, and people live for emotional reasons. If you think it’s perfectly legitimate to come, then at least you should consider the possibility that it should be perfectly legitimate to leave, also for emotional reasons. But in any case, so people leave for lots of different reasons, so that’s one thing that is a stereotype-buster –

David Bashevkin:

And that’s something that the frum world needs to learn about the OTD world.

Philo Judaeus:

Yes.

David Bashevkin:

Meaning, don’t use a caricature, just because somebody is leaving, to project why they left based on the reasons that you learned when you were in seventh grade or tenth grade. You have to really learn their story to understand their decisions, and it’s unfair to cast them into a stereotype. That’s something that the frum world can learn from the OTD world.

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah. And I will say further that it’s often actively harmful to misdiagnosis why someone left. If you relate to them on the assumption that they left because they want cheeseburgers and partying with girls or in cases of girls, partying with boys, that’s not… And really they left for something completely differently, maybe because they’re gay, or maybe because intellectual reasons. You’re going to do it completely wrong. Your relationship with them will be completely off balance if you do it that way. That’s the frum people – That’s one of the things that the frum people can learn from the OTD people, and they learn that OTD people are very normal, wonderful, upstanding people.

David Bashevkin:

And could be well-balanced people, not everyone is, not everybody has their lives fell apart.

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

You could be a well-balanced, healthy person. Let’s go to the other side, and what you think the OTD world could learn from the frum community?

Philo Judaeus:

So a lot of OTD people have had very bad experiences with the frum world. It’s very good, I think, from my perspective, it’s very good for them to interact with frum people who are normal, accepting, wonderful people, who do respect the other people with very different belief systems, and do accept them as wonderful people. When they realize that the frum world is not necessarily that awful world that they experienced –

David Bashevkin:

The same caricature goes both ways.

Philo Judaeus:

It goes both ways. So that’s just one thing. There’s bridge building in ways that I totally don’t anticipate, I honestly don’t know all the ways that it’s useful. People keep telling me that this is such a wonderful group, it’s like… One thing we do regularly, and David, you participate in this as well, is we kick people out, unfortunately, sometimes.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. I happen to love it, that you are such a strict enforcer to make sure that the dialogue is respectful, is not attacking, not attacking religion, not attacking people who left religion. You are the architect to make sure that the bridge, so to speak, remains sturdy and well paved –

Philo Judaeus:

So one of them, yeah. There’s several moderators –

David Bashevkin:

I along with others, but I think you’re the most vigilant. You’re very careful and you’re very sensitive, which I always appreciate, and it really is a lens to the complexity of religious life, but in a deeper way, it’s the complexity of life that you see in the group. Because not everybody’s religious in the group, obviously. So it’s the complexity of what goes into people’s decisions and stories, you see so much there that I find fairly moving.

Philo Judaeus:

I will also just mention that I do run a different group, it’s called Respectfully Debating Judaism, where we do allow, unlike the dialogue group, we do allow people to –

David Bashevkin:

I’m not in that group.

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah. We do allow people to vociferously debate all the details of arguments for and against. But, that’s on Facebook, it’s called a secret group, where you have to be directly invited, you can’t search for it. You have to know about it and you have to, you can message me and I can add you in, but what I’ll do is that any Frum person who asks to join, I will give them a very long disclaimer about –

David Bashevkin:

On why they shouldn’t join or what they need to be prepared for.

Philo Judaeus:

Yeah, they need to know what they’re getting into. Ultimately I say, “Look, this stuff has overturned people’s lives and ruined marriages, according to many poskim this might be completely assur di’oraysah to join this group.” And I give sources for that.

David Bashevkin:

I love that the lilt of your voice still has the Yeshiva’s lilt, which is what I like. You can’t shake it, and it’s something I enjoy a great deal. Philo, we’ve been talking now for close to an hour and a half, and I really want to wrap up now was with some of the rapid fire questions. Firstly, thank you so much for your time, I hope that we have opportunities to talk in other contexts, and the fact that our friendship has survived so much development for both of us is really something I find quite remarkable, and it’s a pleasure and a privilege to call you a friend. Let me end with questions that I ask all of our guests: your basic schedule. What time do you usually go to sleep and what time do you wake up in the morning?

Philo Judaeus:

Can I ask you why, what made you choose that as a question to ask all your guests?

David Bashevkin:

Nobody has asked me that and I’m so not shocked that you’re the first to ask me that. I am very interested in a window to people’s routines and schedules, I think it tells you a lot about a person. It’s more of a structural question, and you find some people have these very rigid answers, “I go to sleep always at the same time, wake up at the same time, I’m a night owl, I’m an early morning person.” I like learning about people, and I think this is an interesting window to learn about people. I don’t know, are you usually a late night person, an early morning person?

Philo Judaeus:

It’s dependent on what I need to do, back when I was going to davening I had to get up much earlier. I prefer not to get up early, if I can help it. On weekends, I will often get up at 9:00, but I typically have to get up at about 7:00 or 7:15 –

David Bashevkin:

And are you a late night person? When do you usually get to bed?

Philo Judaeus:

So when should I get to bed or when do I get to bed are very different questions. I try to get about eight hours of sleep, sometimes a little bit more. I often have to settle for about seven and a half or seven –

David Bashevkin:

Okay.

Philo Judaeus:

Too late.

David Bashevkin:

Okay, that’s fair. Now, you are involved in academia, you – What?

Philo Judaeus:

I’m not directly in academia but I have a research job, yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Correct. So you don’t have a PhD, but here’s my question, I ask all my guests, this question: If you were to get a fully paid doctoral, fully paid, what would you write your thesis on, and what department would it be in?

Philo Judaeus:

So, my wife has long joked with, I agree, that if I had my choice, I would just stay in school for the rest of my life.

David Bashevkin:

I have no doubt that that’s a lot more than a joke, and if you had your way, but if you were to go back and finish a PhD, you could pick any subject, any department, what would you write your PhD on?

Philo Judaeus:

In practical terms, if I do go for a PhD at some point it will probably be related to my work. I am primarily an artificial intelligence researcher, and I focus on artificial intelligence safety. I will probably go for a PhD in that. That’s more of, I think it’s important, and I would do it for my job because I think it’s important, I think what I do is important. Which I’m very fortunate, a lot of people don’t have that. If I would do things because of interest, I would probably, let’s see… Fundamental physics…

David Bashevkin:

You’re a fun guy.

Philo Judaeus:

What?

David Bashevkin:

You’re a fun guy. Fundamental physics is always a –

Philo Judaeus:

No, I would… I don’t really care honestly about getting a thesis, I just want to understand it, like the secrets of the universe, right?

David Bashevkin:

Got you.

Philo Judaeus:

So I’ll just take classes, and if I’m forced to do a PhD thesis, I’ll do it just because I have to. But I know they’re just understanding. And then in philosophy, I probably want to get philosophy of physics, philosophy of religion is cool… Formula epistemology –

David Bashevkin:

Okay this is a dangerous question because you’re just going to list every discipline –

Philo Judaeus:

I’m just going to keep going –

David Bashevkin:

Because you can do this forever. Final question: What book would you recommend that has played an influence on your ability to construct meaning in the world? What is a helpful book, a book that both religious and nonreligious people would find, and that was formative in your life, in helping construct meaning?

Philo Judaeus:

So I will say that I never actually had a problem with meaning, it never actually bothered me. There’s various reasons for that, but I think –

David Bashevkin:

Is there a book that helped contribute to the way that you construct meaning that you would recommend to others?

Philo Judaeus:

So there’s a bunch of them, I will, I can –

David Bashevkin:

We’ll send out all the links, but what’s the one that jumps to mind?

Philo Judaeus:

The book I usually really like is called The Big Picture by Sean Carroll. I don’t remember the subtitle, but I think it has meaning in the subtitle. I think that’s part, one of the words in the subtitle. The problem with that is that it directly argues for atheism. So not very hard, but it does argue for atheism, so I don’t recommend it to people who don’t want to be exposed to that. For people, I mean, honestly, for the people who don’t want to be exposed to that, they probably already have meaning directly from religion –

David Bashevkin:

Is there a book that you would recommend them that, even if it’s not argumentative, but you have found constructive, helpful?

Philo Judaeus:

I’m actually kind of surprised at that because I find it… For a religious person, I think the meaning just comes from religion.

David Bashevkin:

It’s so interesting, it’s not my experience. I mean, a lot of it does, but I find so much meaning from things adjacent to religion, from books, from ideas, but I don’t need to push you on it, if nothing comes to mind.

Philo Judaeus:

It does actually surprise me, but okay, yeah.

David Bashevkin:

This was an absolute joy to spend time and to speak with you. I hope we get the opportunity to do it again. Philo Judaeus, thank you so much for joining the 18Forty Podcast, and I hope you apologize to your wife for me keeping you on here for so long, but thank you so very much.

Philo Judaeus:

Thank you so much, also.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Julia Senkfor & Cameron Berg: Does AI Have an Antisemitism Problem?

How can our generation understanding mysticism, philosophy, and suffering in today’s chaotic world?

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

What Garry Shandling’s Jewish Comedy Teaches About Purim

David Bashevkin speaks about the late, great comedian Garry Shalndling in honor of his 10th yahrzeit, which is this Purim.

podcast

Aaron Kotler: Inside the Lakewood Yeshiva

We speak with Rabbi Aaron Kotler about the beginnings of the American yeshiva world.

podcast

Yehuda Geberer: What’s the History of the American Yeshiva World?

We speak with Yehuda Geberer about the history of the yeshiva world.

podcast

Alex Edelman: Taking Comedy Seriously: Purim

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David is joined by comedian Alex Edelman for a special Purim discussion exploring the place of humor and levity in a world that often demands our solemnity.

podcast

Pawel Maciejko: Sabbateanism and the Roots of Secular Judaism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to historian and professor Pawel Maciejko about the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, Sabbateanism, and the roots of Jewish secularism.

podcast

The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

Micah Goodman: ‘I don’t want Gaza to become our Vietnam’

Micah Goodman doesn’t think Palestinian-Israeli peace will happen within his lifetime. But he’s still a hopeful person.

podcast

Anshel Pfeffer: ‘The idea that you’ll obliterate Hamas is as realistic as wanting to obliterate Chabad’

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu did not surprise Anshel Pfeffer over the last 17 months of war—and that’s the most disappointing part.

podcast

On Loss: A Spouse

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Josh Grajower – rabbi and educator – about the loss of his wife, as well as the loss that Tisha B’Av represents for the Jewish People.

podcast

Bruce Feiler: The Stories That Bind Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to author Bruce Feiler about family narratives.

podcast

When A Child Intermarries

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to a son who almost intermarried, the mother of a daughter who married a non-Jew, and Huvi and Brian, a couple whose intermarriage turned into a Jewish marriage—about intergenerational divergence in the context of intermarriage.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Benny Morris: ‘We should have taken Rafah at the start’

Leading Israeli historian Benny Morris answers 18 questions on Israel, including Gaza, Palestinian-Israeli peace prospects, morality, and so much more.

podcast

Netta Barak-Corren: ‘I hope that Gaza will see a day when it is no longer ruled by Hamas’

Israel is facing several existential crises—at least three, by Netta Barak-Corren’s account.

podcast

Lizzy Savetsky: Becoming a Jewish Influencer and Israel Advocate

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Lizzy Savetsky, who went from a career in singing and fashion to being a Jewish activist and influencer, about her work advocating for Israel online.

podcast

Modi Rosenfeld: A Serious Conversation About Comedy

In this special Purim episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we bring you a recording from our live event with the comedian Modi, for our annual discussion on humor.

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

David Aaron: ‘I believe that the Divine is existence and infinitely more’

Rabbi David Aaron joins us to discuss ease, humanity, and the difference between men and women.

podcast

Yishai Fleisher: ‘Israel is not meant to be equal for all — it’s a nation-state’

Israel should prioritize its Jewish citizens, Yishai Fleisher says, because that’s what a nation-state does.

podcast

Ken Brodkin: A Shul Becomes Orthodox

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Ken Brodkin, rabbi of New Jersey’s Congregation B’nai Israel, about how he helped turn it into “the Orthodox synagogue for all Jews.”

Recommended Articles

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

What is the Megillah’s Message for Jews of the Diaspora?

For some, Purim is the triumph of exile transformed. For others, it warns that exile can never replace the Land of Israel.

Essays

How Orthodox Jews Are Sharing Torah Knowledge Across Denominations

Two programs are already bridging the Orthodox and non-Orthodox divide through the timeless tradition of chavruta learning.

Essays

Ki Tisa: The Limits of Seeing God’s Face

We spend our lives searching for clarity. Parshat Ki Tisa suggests that the most meaningful encounters may happen precisely where clarity ends.

Essays

The American Yeshiva World: A Reading Guide

A guide to the essential books that tell the story—past and present—of the American yeshiva world and its inner life.

Essays

A Jew in the King’s Court: Dual Loyalty in the Book of Esther

The Book of Esther suggests that diaspora is not merely a temporary or anomalous state but an integral part of Jewish history…

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

Why We Need to Live With Radical Laughter This Purim

Brother Jorge asks: Can we laugh at God? We might answer: We can laugh with God.

Essays

5 Lessons from the Parsha Where Moshe Disappears

Parshat Tetzaveh forces a question that modern culture struggles to answer: Can true influence require a willingness to be forgotten?

Essays

How Jewish Communities Can Help Couples Going Through Divorce

Divorce often upends emotional and financial stability. A Jewish organization in Los Angeles offers a better way forward.

Essays

What the 18Forty Team is Reading This Adar

Identity, desire, women in fiction, and more: What we’re reading before Purim.

Essays

The Siddur Has a Lot of Prayers. Where Did They Come From?

Between early prayer books, kabbalistic additions, and the printing press, the siddur we have today is filled with prayers from across history.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

What Haredim Can Teach Us About Getting Off Our Smartphones

Kosher phones make calls and send texts. No Instagram, no TikTok, and no distractions. Maybe it’s time the world embraces them.

Essays

A Letter to Children Estranged From Their Parents

Children cannot truly avoid the consequences of estrangement. Their parents’ shadow will always follow.

Essays

Towards the Derech: How Does a Reform Jew Return?

The “way” of myself and other formerly Reform Jews is unclear, but our desire for spiritual growth is sincere.

Essays

Why Is Meir Kahane Making a Comeback Among Orthodox Jews?

Israeli minister Itamar Ben-Gvir wears the mantle of Kahane in Israel. Many Orthodox Jews welcomed him with open arms.

Essays

The Hardal Community Explained: Torah, Am Yisrael, and Redemption

Religious Zionism is a spectrum—and I would place my Hardal community on the right of that spectrum.

Essays

Between Modern Orthodoxy and Religious Zionism: At Home as an Immigrant

My family made aliyah over a decade ago. Navigating our lives as American immigrants in Israel is a day-to-day balance.

Essays

How Archaeology Rewrote the History of Tefillin

From verses in Parshat Bo to desert caves, tefillin emerge as one of Judaism’s earliest embodied practices.

Essays

Did All Jews Pray the Same in Ancient Times?

Jews from the Land of Israel prayed differently than we do today—with marked difference. What happened to their traditions?

Essays

Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits’ Complicated Portrait of Faith

Meet a traditional rabbi in an untraditional time, willing to deal with faith in all its beauty—and hardships.

Essays

Judith Herman Is Giving Voice to Survivors

Dr. Judith Herman has spent her career helping those who are going through trauma, and has provided far-reaching insight into the field.

Essays

3 Questions To Ask Yourself Whenever You Hear a Dvar Torah

Not every Jewish educational institution that I was in supported such questions, and in fact, many did not invite questions such as…

Recommended Videos

videos

Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin: How Torah Gives Us Faith and Hope

In this special Simchas Torah episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin—parents of murdered hostage Hersh…

videos

A Vulnerable Conversation About Shame, Selfhood, & Authenticity with Shais Taub & David Bashevkin

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Shais Taub, the rabbi behind the organization SoulWords, about shame, selfhood, and…

videos

An Orthodox Rabbi Interviews a Reform Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue, about denominations…

videos

The Hasidic Rebbe Who Left it All — And Then Returned

Why did this Hasidic Rebbe move from Poland to Israel, only to change his name, leave religion, and disappear to Los Angeles?

videos

Why Naftuli Moster Left Haredi Education Activism

We speak with Naftuli Moster about how and why he changed his understanding of the values imparted by Judaism.

videos

Moshe Benovitz: Why Religious Change Doesn’t Always Last

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, recorded live at Stern College, we speak with Rabbi Moshe Benovitz, director of NCSY Kollel,…

videos

Is Modern Orthodox kiruv the way forward for American Jews? | Dovid Bashevkin & Mark Wildes

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Mark Wildes, founder and director of Manhattan Jewish Experience, about Modern Orthodox…

videos

Torah Study and ChatGPT: How Should Jewish Education Respond to AI?

On this 18Forty panel, we speak with Alex Jakubowski of Lightning Studios, Sara Wolkenfeld of Sefaria, and Ari Lamm of BZ Media…

videos

Moshe Gersht: ‘The world of mysticism begs for practicality’

Rabbi Moshe Gersht first encountered the world of Chassidus at the age of twenty, the beginning of what he terms his “spiritual…

videos

Mysticism

In a disenchanted world, we can turn to mysticism to find enchantment, to remember that there is something more under the surface…

videos

What are Israel’s Greatest Success and Mistake in the Gaza War?

What has been Israel’s greatest success and greatest mistake?

videos

A Reform Rabbi Interviews an Orthodox Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko (Part 2)

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue,…

videos

Moshe Weinberger: ‘The Jewish People are God’s shofar’

In order to study Kabbalah, argues Rav Moshe Weinberger, one must approach it with humility.