Rabbi Shalom Carmy: How I Ground My Faith

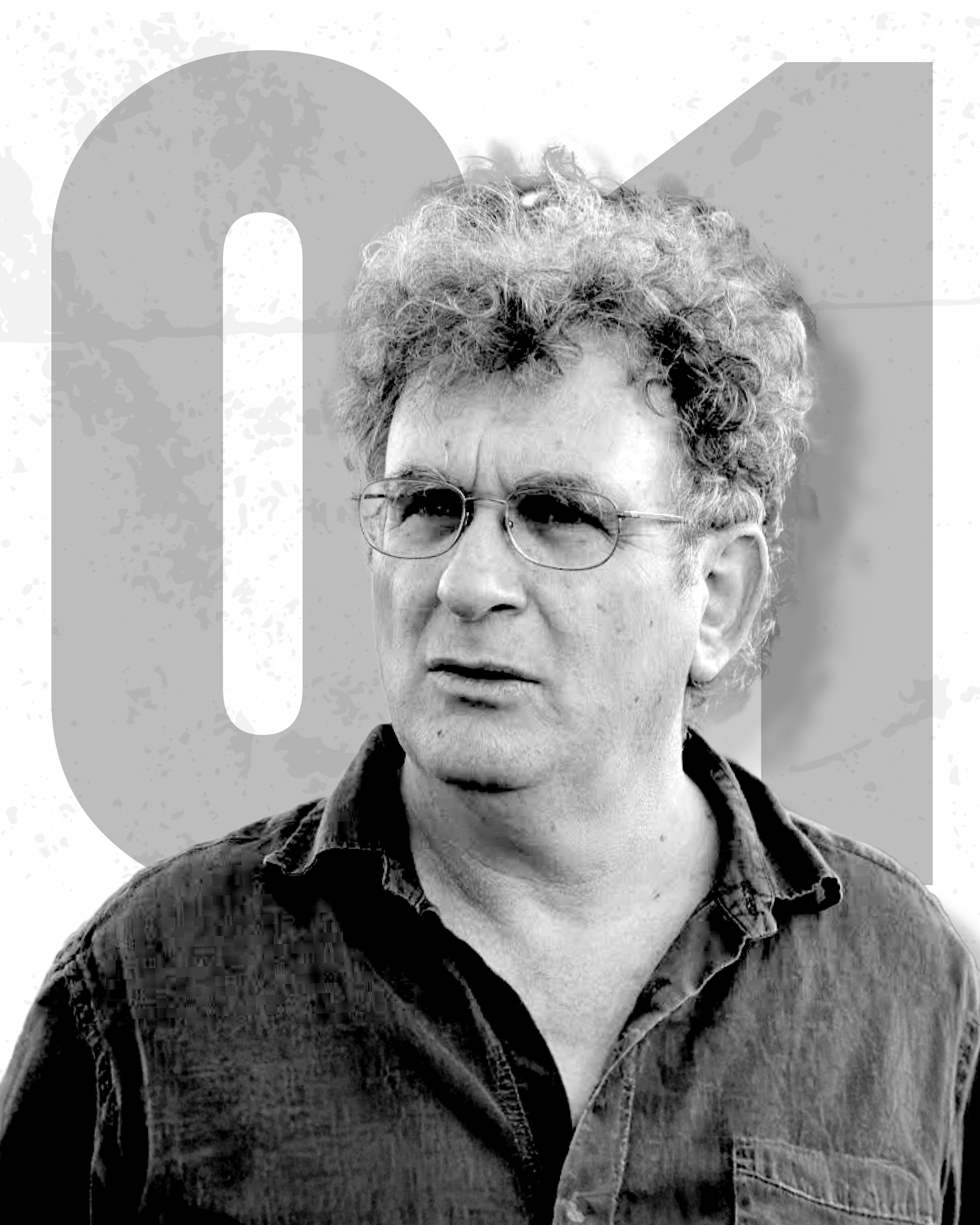

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Shalom Carmy—philosophy and Jewish-studies professor at Yeshiva University and Editor Emeritus of Tradition—about how he grounds his faith.

Summary

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Shalom Carmy—philosophy and Jewish-studies professor at Yeshiva University and Editor Emeritus of Tradition—about how he grounds his faith.

Rabbi Carmy joins us to discuss the anthropological, covenantal, and experiential bases for religious belief.

- What should be the foundation of a person’s faith?

- What is the role of personal experience in relation to rational inquiry?

- How can we reinvigorate our religious outlook for the modern world?

Tune in to hear a conversation about how we handle questions that don’t come with definitive answers.

Interview begins at 14:04

Rabbi Shalom Carmy is a rabbi and professor, teaching philosophy and Jewish studies at Yeshiva University, where he is Chair of Bible and Jewish philosophy at Yeshiva College and an affiliated scholar at Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. Shalom is Editor Emeritus of Tradition, Contributing Editor of First Things, and has published hundreds of articles on Jewish thought, Tanach, and other subjects, along with being the mentor of many students over his years of teaching.

References:

Chidushei Rabeinu Chaim Halevi – Rambam by Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik of Brisk

“A Room With a View, But a Room of Our Own” by Rabbi Shalom Carmy

“A Peshat in the Dark: Reflections on the Age of Cary Grant” by Rabbi Shalom Carmy

“Editor’s Note: Homer and the Bible” by Rabbi Shalom Carmy

“Of Eagle’s Flight and Snail’s Pace” by Rabbi Shalom Carmy

“Editors Note: Lost Cause: A Conclusion in Which Nothing is Concluded” by Rabbi Shalom Carmy

Henry More: The Rational Theology of a Cambridge Platonist by Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein

David Bashevkin:

Hello, and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast, where each month we explore a different topic, balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host, David Bashevkin, and this month we’re exploring rationality, returning back to this topic that we explored so many months ago.

This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big juicy Jewish ideas. So be sure to check out 18forty.org where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails. There is always a danger in getting to know a writer exclusively from their writing, having never met them in person. And one of those people happens to be today’s guest. I grew up in the shul of Rabbi, Dr. Walter Wurzburger, who maybe some of our listeners remember, he was originally a rav in Canada, in Toronto, I believe in Shaarei Shomayim. And he was the second editor of the journal Tradition after Rabbi Lamm.

So, when I was growing up, I mean, it was all over our shul. We would have these old Tradition journals and my grandfather, Rabbi Moshe Bakriski., used to have the old issues all over his office. Actually, after he passed away, I got all those old issues. I didn’t get a lot from my grandfather, but what I did get were all those old Tradition journals and they’re absolutely a treasure.

I also think I got a first edition Reb Chaim Brisker al HaRambam. I don’t know if that’s worth anything. It was like kind of taped up and beat up. But I did get, and I’ve always treasured, my set of Tradition. The Tradition journals, and I’ve had them all. And I grew up reading them. Really from a pretty young age, Tradition was pretty highfalutin, Modern Orthodoxese, which is a language Modern Orthodoxese. You have words like ontology and epistemology.

I think the first time I learned the word axiomatic was from an essay written by a rosh yeshiva at YU Rav Mayer Twersky, who wrote an article about the Sefer HaChinukh, that begins with, I think it was even in the title, “Axiomatic.” And I remember looking it up in the dictionary. It was probably in ninth or 10th grade, and I would read just articles, issues month after month. And I really love them.

There’s one writer who I knew I always wanted to love, but sometimes struggled quite mightily to get to the depths of what he was saying. And that was Rav Shalom Carmy. Rav Shalom Carmy has this style of writing that is so sophisticated, so creative, so deeply thoughtful, almost like when the old romantic movement, the way he writes about religion, is almost inimitable. I haven’t seen anybody write about davening, about yirat shamayim, about topics of the awe and relationship with God, quite like Rav Carmy.

And when I used to read Rav Carmy’s writings, I guess in my head, I conjured up this image, honestly, like the person on the box of Quaker Oats. Remember that old Quaker looking person, I lived across the street from somebody else named Carmy Schwartz, who always still, to this very day, when I think of davening on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, I hear Carmy Schwartz’s voice, I grew up with his voice.

So I think as a young kid, I would get them mixed up. I thought they were the same person, Carmy Schwartz and Shalom Carmy, and Carmy Schwartz has this regal, old world institutional leader to him as a former head of the Jewish Federation. And I remember, when I finally came to Yeshiva University and met Rav Shalom, Carmy, not Carmy Schwartz, but Shalom Carmy for the first time, I was like, “Oh, I expected somebody, I don’t know, who looked like one of the founding fathers. Who looked like George Washington.”

And Rav Carmy is very plain. Very understated. He’s not taken to fanciness. He doesn’t look, his storm into a room like you’d imagine an Isaac Newton or Voltaire, or, I don’t know, Thomas Jefferson, which is kind of in my head, a combination of all these figures. He kind of sits unassuming, self effacing, and is one of the most brilliant spokesmen for religious life and religious thought. We have spoken about many of his essays in the past, one that we have quoted many, many times that is available on Amazon, is a brilliant essay that he wrote called “Forgive Us Father-In-Law for, We Know Not What to Think: Letter to a Philosophical Dropout from Orthodoxy,” and that is available on Amazon.

And it is an article that we discuss in this episode about somebody who dropped out from Orthodox Judaism, exclusively for ideological reasons. For philosophical reasons. He had a good thing going, he enjoyed it, he liked it. But he couldn’t actually commit to the philosophical premises of this movement. And, he has a way of articulating the methodology and the thought of how you arrive at religious conclusions that I find absolutely fascinating. Which is why when I read his contribution to Jeff Bloom’s book, Strauss, Spinoza, and Sinai, which we’ve been discussing so much, and his article, which we discussed in this episode, is very dismissive of this approach.

In fact, in many ways, it reminds me of a voicemail that we got after our interview with Jeff.

Listener Voicemail:

David, I’m very excited that you return to the rationality topic. I love this topic. But I always question all these arguments. Like Strauss, that we need to have different assumptions, we can’t use the assumptions of modernity to prove it. Or that we can’t use logic to prove God, because logic is a creation itself. We can’t use our language to describe God, because language is a creation, and God is higher than that.

All these kind of arguments are good for people who like where they are. They like Judaism. They feel in good place. They just want to know that this might be true. It’s not a total scam. It’s not a farce. But, for people who are raised that they are sacrificing theirselves for the capital T truth, and they give away everything of their life for that. Because it’s true, you can’t just tell them that it might be true.

I mean, Strauss is not an argument against Christianity. It’s not an argument against Reform Judaism. It’s not an argument against any other religion. It just tells us that Orthodox Judaism might be true. So, if you like it, I can still be here, and know it’s not a total scam, like this Jeff Bloom said. He wanted to be here. Just wanted to know that it might be true. But for someone who was raised, “Okay, give away everything from your life.” Being coy for 10 years, because “this is the truth,” when you can just tell them, “Oh, this might be true.”

David Bashevkin:

And I think this voicemail is very fair. It’s basically asking, “You’re leaning too much on the experience and not enough on the philosophy.” And I think that there’s no one who’s able to understand and better articulate how these two worlds intersect, compliment one another, even though I don’t think Rav Carmy agrees, as we will explore in this interview, that they can be entirely extricated from one another.

I do believe he understands that these are two very different conversations. And I guess for some of our listeners who may not be familiar with Rav Carmy, Rav Carmy is one who is a fine wine that is best by in writing. He is not a inspirational or motivational speaker. I think he’d be the first to admit that, there’s something very understated, and very uncomfortable with talking about himself. He has a phenomenal article. All of his articles are really phenomenal. I’m going to pull out a few.

But, one thing that makes his article so amazing are there titles. He has the best titles for his articles. He has one article called “Homer and the Bible,” which I mentioned, which we discussed in our conversation with Rabbi Daniel Feldman in our series on humor. And his article on “Homer and the Bible” does not refer to the philosopher Homer, but of course, to our beloved friend, Homer Simpson, and recalls back a classic episode where Homer is using his own familial relationship and experience to get students attention.

Homer Simpson:

Well, you see marriage is a lot like an orange. First, you have the skin, then the sweet, sweet, inner—

Apu:

I don’t understand.

Willy:

If I wanted to see a man eat an orange, I would’ve taken the orange eating in class.

Hans Moleman:

The eating of an orange is a lot like a good marriage.

Abe Simpson:

Just eat the oranges.

Skinner:

This is terrible.

Mayor Quimby:

Let’s get out of here.

Skinner:

A terrible excuse for education.

Homer Simpson:

I told Marge this wouldn’t work the other night in bed.

Skinner:

In bed?

What?

Moe:

So something wasn’t working in bed, huh? Heh, heh, heh.

No, that’s not what I meant. Marge and I always talk things over in bed. Like the other night we were fighting about money.

David Bashevkin:

And Rav Carmy laments what Homer Simpson is doing here, that so often we need to call upon our own self revelatory experiences in order to keep our students’ attention. Cause they’re not necessarily interested in the nitty gritty conversations about the foundations of faith itself. But I do want to highlight a few of his most important articles that for our listeners, at least in writing, are worth reading. If you’ve never been exposed to Rav Carmy’s writing before.

You can go to Tradition‘s website, which has an unbelievable catalog of all of the archives. Tradition‘s website, of course, is traditiononline.org, where you can find the classic journal of Orthodox Jewish thought. Again, traditiononline.org. Rav Carmy was the editor of Tradition. First it was Rabbi Lamm, then Rabbi Walter Wurzburger, then Rabbi Dr. Emanuel Feldman, and we will get to him of course, soon in this series. And finally Rav Carmy.

And now, it is our friend Jeff Saks, who of course we will have on one of these days as well. But, if you want to really explore Rav Carmy’s thought, and I would begin with his editor’s notes that he wrote for so many years in the introduction to Tradition. And I want to pull out some of his most important articles, which I think our listeners would gain from. There’s one article. That’s entitled “A Room With a View, But a Room of Our Own,” and this is an exploration of how traditional communities should explore Biblical criticism.

I think it’s an absolutely brilliant essay. I’ll just read a small part from it where he actually quotes from Rav Kook, as he does a great deal, and quite often, in his articles. He quotes Rav Kook in a letter, Rav Kook wrote. And in general, this is an important rule in the struggle of ideas.

“We should not immediately refute any idea which comes to contradict anything in the Torah, but rather we should build the palace of Torah above it. In doing so. We are exalted by the Torah, and through this exaltation, the ideas are revealed. And thereafter, when we are not pressured by anything, we can confidently also struggle against it.”

This essay Rav Carmy writes can be read as an extended commentary on these inspiring words of Rav Kook. Our immediate and primary goal in confronting unsettling ideas is neither impatient or anxious reputation, nor is it paralyzed silence. We are to get on with our learning, to integrate the challenging ideas insofar as this is warranted, into the seamless fabric of our derech halimud. What a beautiful articulation of the work that we strived to do in 1840 and the work that Rav Carmy did for so many years. And he concludes this article, once again, “A Room with a View, But a Room of Our Own,” which is a rumination on approaching Biblical criticism.

He writes, “I return to Rav Kook’s fascinating image of the palace of Torah that expropriates the challenge of ideas, contradicting Torah. I wonder if these words do not intimidate us as much as they spur us onto greater and more authentic achievement. Unable to build a palace in one fell swoop, we build nothing and call for a deus ex machina,” which I don’t know if I’m pronouncing that correctly, but basically means, some event that hopes to resolve a seemingly hopeless situation.

“To call for a deus ex machina, to fill the void and get us off the hook. Our derech halimud must be built, example after example, brick on top of brick, before we build the palace, we need a place where we can unpack our trunk, get our books out of storage and back into our hands. We want a room with a view, since there is knowledge to be had, that we want to have for our enhanced study of Torah. But we cannot do our work. We cannot prepare to build the palace unless we do it in a room of our own.”

And in some ways I think this community is a room with a view, but a view of our own. So the community of listeners, the community of 1840, such beautiful language of building that palace, even upon contradictions and difficulties that we may find in theology or in our lives, but still being willing to build that palace.

There is another article that is absolutely brilliant and worth reading. Again, a rumination on some of these trickier theological conversations. And the title is absolutely adorable. It is called “A Peshat in the Dark: Reflections on the Age of Cary Grant.” And of course, that header, “A Peshat in the Dark,” is a awesome, tier-one pun on a shot in the dark. Just an absolutely brilliant title. And that article too, I would recommend.

I’ll just share one more aside from the ones that we’ve already shared, and that is “Of Eagle’s Flight and Snail’s Pace,” which is really talking about how we approach modernity and religious thought in general. But again, I would go to Tradition online, and really take time his articles on prayer, his articles on yirat shamayim, the awe of God, articulate a sort of authentic religious relationship that I have struggled to find anywhere else in the English language. And it’s really an absolute pleasure and privilege to introduce our conversation with Rav Shalom Carmy.

What we’re talking about this month is we’re revisiting a topic that we actually explored a few months ago, and that is how to ground, or can you ground your religious faith, particularly Orthodox Judaism in something rational. And we’re talking about this topic this month through the lens of this incredible book that you contributed to, called Strauss, Spinoza, and Sinai: Orthodox Questions and Modern Questions of Faith. And your approach, in this article, I found to be absolutely fascinating. And I want to talk about what you wrote here and then maybe broaden it to some of the other religious writing and ways that you’ve grappled with this issue.

But essentially, your article and contribution, which is charmingly titled, let me just say, the titles for your articles are always the very best. It’s an area. I wish that you were recognized for more. I think my favorite was “Homer and the Bible,” which is a play on Homer, not the philosopher, but our favorite Homer Simpson. But all of your articles, I always love your titles.

And in this article, which is entitled, “An Argument for Businessmen,” you reject the notion that finding some plausible, possible way for grounding your faith, that it might possibly be true, is not the way to approach faith. It’s the way that you would approach an actuarial table, but it’s not the way that you would ground faith, necessarily. The sentence that you write that jumped out at me, “Why asserting this bare possibility offers comfort to the believer, or encourages belief in revelation, is a mystery to me.”

So I guess the place to start is a very broad question that you have weighed on in so many eloquent ways, not just in this article, which is a critique, but in your books, in things that you’ve edited, which is, how would you ground someone’s faith? If someone came to you and said, “Look, I like being an Orthodox Jew. It’s nice. The kugel’s nice. The cholent’s nice. I like my shul, but this doesn’t seem true or real.” Where would you start to ground someone’s faith?

Shalom Carmy:

To begin with, you have to start from experience. My criticism of Strauss is that his idea of the relevant kind of experience is very, very narrow. Within the real world, there’s a confluence of various factors that lead people to believe whatever it is they believe. We go elsewhere for a moment. The question is, “Is so and so my friend or not.” I could give a kind of QED mathematical truth. The person who’s done X, Y, and Z on my behalf, therefore they must be my friend. And there’s no other explanation of why they would’ve done the following things for me.

Usually though, there’s a combination of different factors. A person may do beneficial things for me. I may enjoy the person’s company, which is not really relevant because I can enjoy somebody’s company and it can be very bad for me. I add up a variety of factors. And a certain point, I say, “This is the way I see the world. This person is on my side.”

David Bashevkin:

My issue is that for a lot of people, the people who I’ve at least spoken to, who are grappling with this question, in their life, in their experience. They’re not looking for a specific equation, but the problem is they have seriously conflicting evidence. And the most difficult evidence that I feel a lot of people grapple with, which isn’t at the forefront of this book, though I know Jeff mentioned it as a part of his personal journey, the editor. Our issues related to Biblical criticism, our issues related to the fact that we don’t have any clear revelation of God’s presence.

But I think the thing I hear most often that kind of chips away at people’s sense of faith, or what I love, sense of friendship with faith, to use your language, is there seems to be evidence in direct contrast to the Orthodox values that we seem to preserve within our community.

Shalom Carmy:

I think for those people who are, maaminim, at least as I see it, there are three major areas that are important for them. Or a combination of them. One is what I would call religious anthropology. You have a certain idea of what a human being is about. Put it very simply, in the language of Pascal, we are both above the animals and below the animals. There’s something and a dignity of the human being, or in transcendence of the human being, that is more than simply biological.

And at the same time, we’re not angels. We’re capable of great evil. Even those of us who are not evil people can be attracted by its struggle with it, and so forth. Once you have such a conception of what a human being is about, and then you’re willing to consider the possibility of God, and you ask yourself, “What would God want people, what kind of law would God give people?” And the answer to me would be, that it would be the kind of law, the kind of regimen that on the one hand would have some very specific commands in it.

I’m not God’s brother-in-law, I may be his son, but not his brother-in-law. Or as Kierkegaard put, in different conception. Each person regarding himself is his father, and not his uncle. If God is God, then God makes demands. At the same time, my understanding of human being is that the human being has to be engaged creatively, intellectually, emotionally. We are not simply robots doing what we’re commanded.

So, such a divine revelation would involve specific demands. Not all of which would make sense or appeal to us. It would also call upon us to be intellectually and emotionally engaged, to do some of our own work for ourselves to be on our own. You would have an outlook that would recognize both the majesty of the human being and the debasement of the human being. It would have an individual quality that relate to God as one individual reaching out, the alone to the alone, as Plotinus put it.

It would also have a social dimension, because human beings are social creatures. It would involve what we know of as klal Yisrael. So those elements, I think are, call them as anthropological. It means you look at the Torah, and you look at other options, and within a Torah, you have something that appeals to, and makes demands on, the human being in a full complexity. For some people that is a very powerful argument. Biographically, I would say it was very important for me.

Now, how do you reach such conception is, be a purely intuitive matter. You’re born thinking that way. Or, it can have something to do with thinking and reading and so forth. You look at literature, you look at philosophy, you see the way the sharpest intellects and most eloquent intellects have tried to make sense of the world. And you situate yourself in that framework.

If I would mention names, outside of the world of general literature, if you really read Rav Soloveitchik’s major works, carefully, I think that’s what’s going to come across. He’s describing a certain way of thinking, a certain mode of relationship. I think in strike, one is realistic. The second area, which I think is very important for many people, is the story of klal Yisrael.

I could very well see Christians, and I know Christians who may not be committed, some of the spoke devout Christians. But if they look at the world, they say, “Somehow God’s involvement is most manifest in the story of Jewish people.” Whether there’s a later revelation through Christianity, that’s not my concern right now, but they’ll recognize that here is where God breaks into the world.

And, then thirdly is a question of what you might call religious experience. I don’t like the word mysticism, but you could use it here. Moments when people have a sense that coheres with these other factors. And that’s, again, you could claim it’s an illusion. When I think about it, it’s three o’clock in the morning, maybe my imagination. But together with these other factors, I think it creates an entire way of thinking. And if you rely on that totality rather than one particular line of reasoning, you will get a sense of what religious life is about.

I think the problem for many people is that once they get down to work, they end up with a very narrow conception of what counts as evidence. Sometimes I’d be very skeptical, but we always find reasons why this intuition of that intuition is worthless. Spinoza recognized that Jewish history is very special.

And he said, “Look, there’s nothing really special about it. These people have their peculiar laws to which they’re stubbornly attached. They have circumcision, which for certain reasons,” he lists separately from other mitzvot. And if you take that away from them, in a generation or two they’ll be just like everybody else. None of this uniqueness, it’ll evaporate. On the other hand, you can say, no disrespect to Spinoza. I know what I know, and I experience what I experience.

Now, the same people, when it comes to securing their academic position and personal relations, and so on. They’re not quite that skeptical. In those areas, it can be very down to earth and very intuitive.

David Bashevkin:

With marriage, friendship, the examples you used earlier.

Shalom Carmy:

Yeah. And their people will be shrewd and they’ll ask different people. They’ll weigh different factors, and sometimes they’ll make terrible mistakes. The fact you’re doing something the right way does not guarantee that you get the right results.

David Bashevkin:

I wanted to ask you, you had mentioned what had really inspired you. And, there is something, we only know each other from a distance. I grew up reading your articles. Probably not understanding them till I was much, much older. And even now I still struggle to really plumb the depth. But you’ve always been a transcendent religious personality, really in my own life.

And I mean that not to flatter you, but really to show some measure of gratitude, to the language that you’ve used to describe religious commitment and religious ideas, has always been with a deep grandeur, ever since I was a kid growing up in the shul of your mentor, Rabbi Walter Wurzburger. Who I was too young to engage with has even, I was really a child. But my mother would always encourage me to reach out to him.

But there’s something about your career and your contribution to Orthodox thought that both has made you into an address for people who are seeking and grappling with doubt. And underneath, at times, I have detected, not religious doubt, but almost doubt of fatigue, of whether or not we can actually achieve the grandeur of the religious vision that you have embodied in so much of your writing and life.

I’m talking about two things. One is an article that we have surfaced and come back to many times, on 18Forty, and that is what you wrote for ATID, which to me is a cousin, if not a sibling, to what you are describing now. And to your contribution, an argument for businessmen, and that is the article that you could buy on Amazon now, we’ve linked to it on more than one occasion. Forgive Us Father-In-Law, For We Know Not What to Think: Letter to a Philosophical Dropout from Orthodoxy.

Which is presented as a letter, ostensibly, from a student who’s grappling with these issues. He doesn’t have any gripes with the experiential world of Orthodoxy. His gripe’s with the truth, with the rationality of this community and reached out to you. Now, we discussed a little bit beforehand, I asked you if this was an actual student, and you said, you told me that it really, really was. But, what fascinated me is, who does reach out to you and with what doubts do they reach out to you with?

You’ve become an address of sorts for those in the know to reach out and try to find some religious truth. So I’m curious before I get to the question about your own doubt that I have detected in your writings ever so gently hovering beneath the surface, I’m curious if you could tell us a little bit of this story about this student and maybe what kind of doubts you hear from people who reach out to you religiously.

Shalom Carmy:

This particular student, the question is not so much doubt, as a kind of tone deafness is too strong, a word, but, an unwillingness to engage experientially. Use word experience before to the degree that he likes being in the Orthodox community, you’re right. As he put it to me, and I did not include that, I don’t think I included that in the essay. He certainly would not want to disappoint his parents. He would not want to marry a woman who would not share that involvement. He would want to raise his children a certain way. That has nothing to do with religion that has to do with lifestyle. I could like a certain lifestyle without any of the beliefs that would normally come along with that.

His problem was that intellectually, none of this meant anything to him. The way his mind worked, any experiential argument for religion is refuted, mean and they, automatically because any such argument would only tell him about what he wants, not about what is true. If the human being is really isolated in that way, then, whatever you look at is going to be a mirror. And the problem with that is, in his case, I don’t think is narcissism, where you look in the mirror and you become infatuated with yourself. If I thought he was that kind of person, would’ve been harder for me to respond at length.

It’s very easy to dismiss, say, “This is wrong with him, that’s wrong with him.” But it’s really an epistemological problem. No matter what you say, it’s going to be what you say. And if it is at all possible to have a different way of thinking, then why should, what you want to be true, be any better than what somebody else wants to be true. That is a much broader problem, and I think people realize.

You take all people who are fascinated by the notion of virtual reality. That means the world is not true. Nothing exists. I am alone in the world, and the world happens to be arranged in such a way that I’m led to believe that X is true and y is true. If you’re thinking in those terms, you have a trap that not only will refute religious belief, because it doesn’t prove true religious belief, but will make it impossible, imaginably, to relate to religious beliefs.

Again, in the history of philosophy, there are people who were solipsists. It’s conceivable for me to think that other minds don’t exist. Alvin Plantinga’s first important book on the import and philosophy of religion, was God and Other Minds. He raised the question, “How do I know that other people exist?” And you recognize that many philosophers have great difficulty with that. So, in that case, if I worship God, I’m really worshiping some idea in my head. If I’m married, I’m not really married to a person I’m related to an idea.

Again, I think most people don’t think in those terms. Most people would say, “If you only gave me a little more evidence to swing that way, then I would buy in.” But underlying that seems to be the premise that no matter what kind of evidence you will give, or what kind of experience you’ll give, you’ll remain with yourself. My response was based on that premise, which means two things. One thing is that I, in that essay, I was arguing for much less than I appeared to be.

I think I’ve said to you, I’ve said to many people, “Analytic philosophy is trench warfare. You fight, and you fight, and you fight, and you move the front a few inches and then you have another fight and you retreat a couple of inches. And ideas after several years, eventually, either, there’ll be a breakthrough or the enemy will starve.”

Most recent work on World War I is that Germany was not in that bad an economic situation. Whatever the point is, it’s a long, long process, and you establish very little. Although cumulatively, it may end up going somewhere, eventually. So in that essay, I was trying to be very analytic. My goal was not to discuss what is true or not true. My goal was to raise a question.

If you are in its particular position, namely, you’re starting out from absent skepticism, assuming that’s possible. On the other hand, you have some reason to try to latch onto this Judaism business. Then, what’s the reasonable next step? And to me, the reasonable next step is find out more about it. Experience it more fully. You don’t experience it. You’ll be missing the most important dimension. That was the argument I was making.

Now, in the middle, I may have been smuggling in something of my own reason, what I consider important. But the major argument was, if you are a rational person, where do you start? You don’t start from pure reason, because you’re a human being. A human being is a combination of a lot of factors. You have a large tool kit, to use a phrase that I borrowed from Wittgenstein. That includes various intuitions, various modes of reasoning. And you use whatever’s in that kit. And part of that kit is understanding what’s really the issue of religious people.

And here, I would say, and I didn’t emphasize this earlier today, that very often, especially, we think in terms of argument and proof and so forth. We miss out on the experiential aspects of religious life. When you look at real religious people, there’s something about them that you have to be exposed to. You have to study, you have to relate to, in order to either reject them or accept what they’re doing. From that point of view, studying history and literature, may be, chas v’shalom, better than studying philosophy.

David Bashevkin:

It actually leads me to where I really want to get to, which is, I guess it’s something I’m grappling with. I don’t want to superimpose my own doubts on what I may hear whispers beneath your own words. But I can’t help but think that you live in rarefied religious air. You have been exposed to the greatest mentors, obviously Rav Soloveitchik, Rav Aharon Lichtenstein, Rabbi Walter Wurzburger. You have been immersed in the greatest of philosophy and literature.

And what actually puzzles me to a degree about you, is how the experience remains so rich when, and again, I am maybe guilty of superimposing my own struggles onto what I sometimes hear you grappling with. Is that when you look out into your average Orthodox community and you go to Bergenfield and you go to, I don’t know, some major, I don’t mean to single out Bergenfield or the Five Towns, Boca, anywhere. A lot of the majesty of religious life is not there. You don’t necessarily imbibe it. You don’t necessarily see that beauty that maybe you are able to describe so eloquently in your words.

And, I sometimes sense, I don’t want to call it doubt, but almost fatigue. In your concluding article, as editor of Tradition, I could not help but notice that the title of that article was “Lost Cause: Conclusion in With Nothing is Concluded.” And I sensed a bit of fatigue in almost, can we ever be successful in moving the Orthodox community and what values we embody and experience.

So that the experiential world of Orthodox Judaism actually matches up with the values that are so faithfully transmitted, by these rarefied individuals, which. I will include you in. And you would include Rav Soloveitchik, and Rav Aharon Lichtenstein., and Rabbi Walter Wurzburger, and your mentors, and people who inspired you. But then sometimes you look out, and it’s the experience itself, which is left wanting. And, you feel like there is a majesty in religious life, but who are my brethren and arms in this?

And I’m wondering for you, how do you find nourishment in the experience of contemporary Orthodox life? Maybe I’m totally wrong maybe. Or maybe that’s why the academy, where you have built your life, has been so comforting and nurturing. But for many who reach out to me, at least, they’re not in the academy anymore. They’re not in the beis medrash anymore. They’re in your local synagogue, your local shul, and they look around, and the grandeur, which I think you do capture, and our teachers and these individuals do capture, is so often wanting in those spaces.

So, I’m curious if that’s something that you’ve ever grappled with? And do you think in a way that the grandeur of religious experience is a lost cause of sorts?

Shalom Carmy:

First to go back to the title, the phrase “lost cause” is not mine. I borrowed it from T.S. Eliot, as I made it very clear in the article.

David Bashevkin:

Yes.

Shalom Carmy:

And T.S. Eliot wrote, in a passage that they quoted from his essay, “In Pitch Bradley,” “there is no such thing as a lost cause, because there’s no such thing as the one cause.” Which that’s the nature of life. The most important causes, you don’t get an immediate up or down. As we’re speaking, it just occurs to me at this very moment, would Abraham Lincoln or Frederick Douglas have thought that they were dealing with a one cause? And if they did, they may have been a little premature. I mean the real issues, and I’m not saying this as a left winger, I’m not, but if you think of the history of enslavement as a serious problem for the American ideals of democracy, this has not gone away easily.

And people are struggling on these fronts. Whether I agree with their tactics, or their goals, or not, those are them are realistic know that there are, this is a very long battle. The other factor in the title, “Conclusion, Which Nothing is Concluded,” really makes the same point that’s taken from Samuel Johnson. The last chapter of his novel, Rasselas, it’s called “A Conclusion in Which Nothing Is Concluded.” I’m not as original as I pretend to be.

Part of, what you’re asking, I don’t think you’re asking directly is, biographical. I think that one reads everything that I’ve written realize that there was certainly a stage, whereas I put it in my eulogy for Rav Lichtenstein, how my life would turn out was not a foregone conclusion. There was a lot in the Modern Orthodoxy, way, way back, that seemed very indifferent. Didn’t seem to be serious at all. It seemed to be sociological.

I’m not speaking only in terms of shemirat mitzot, but in terms of deeper attitudes, there was much that you could satirize, and much I probably have satirized in the course of my life. The rebbe of mine who people usually don’t mention that quickly was a factory worker who in a period when shemirat Shabbos was fairly rare in the immigrant communities, he not only was shemirat Shabbos, but he found time to learn Gemara every day, and—

David Bashevkin:

Who is this? This was your actual rebbe?

Shalom Carmy:

It’s my father.

David Bashevkin:

Ah, okay.

Shalom Carmy:

My father. He was able to, having left formal education at the age of eight or nine, because of poverty, as I understand it. He was able to reach a point where he could give a shiur to balabatim. It may not be the kind of shiur you would have today, where you quote a hundred Acharonim. His library was limited. He knew what was important to him, what wasn’t. But he was able to do that. And he was serious about religion. It’s a memory that I had with me.

For some reason, it’s always spring time, or fall, maybe because that I was home at that time. His Mincha-Maariv, it wasn’t that early as it would be in wintertime or as late as it would be in the summertime. But I remember him standing in the living room, davening Mincha, davening Maariv. And I don’t think I understood very much about the philosophy of tefillah, what I read in the love or other writers. I didn’t even know that much about the halacha of tefillah, but I understood that this was serious business. And that for him, these things were serious business.

Nonetheless, see later on, I learned a little bit more about the politics of religion, and it was not edifying. It was not edifying at all. I wrote to eulogy for Rav Ovadia Yosef. What a certain point in my development was a kind of breath of fresh air. There was a certain integrity to him. A certain down to earth quality to him. And that even some of the factors that I later grew away from, in terms of his way of characterizing opponents, even that struck me as being refreshing in a certain way.

Now, I could have learned other things from him, things that I’d be ashamed of having learned. But, these were people that I looked at. There were teachers that I had. May not have been the most brilliant people in the world. Some of them were very bright people, let me tell you, and that meant something to me. It also meant something to me that I never felt, that I am obligated, and if I want to be frum, that I have to shut out any other kind of wisdom.

In that sense, there’s a certain kind of frumkeit that I did not get at home. Thank God. There is a certain kind of narrowness that I was not given at home. And Rav Lichtenstein, in his essay “The Source of Faith is Faith Itself,” he mentions, towards the beginning that he grew up in a home, it was a home where there was a lot of pressure on him to succeed in all respects. But he grew up in a home where his parents could speak very openly about things that are wrong in the community without any snideness, without any cynicism. But he grew up knowing this is the way things are, and nobody, at least the people who were responsible for him, did not feel the need to hide that.

So these are issues that affected me early. When I looked for the rabbeim whom you mentioned earlier, I looked for them precisely because I already had some idea of what kind of person I’m willing to learn from, and I’m willing to take seriously. If you would ask me about the metaphysics and epistemology involved, I don’t know if I would’ve done a good job. But I understood that if I’m serious about these things, just as it was important for me to learn from my father.

This was important for me to learn from a lot of other people. Learn a lot from people. It was also important for me to try to figure out what somebody like Rav Lichtenstein was about. What something that I was about. Or something from what Wurzburger is about. What, I don’t want to mention names, but what some of my friends who are my age. And these are people that I valued very much. Had a great impact on me. Your people sometimes cocked an eyebrow at me.

And, instantaneously, I realized that the way I had been thinking before was not the only way of thinking, and it’s probably the wrong way of thinking. So that’s very important. Now, if you want to do that, again, I was fortunate that I had those opportunities. There are people who don’t have those opportunities. I mentioned in a recent article, a young man, baal teshuva, who asked me at one point, he said, “Now that I reached wherever I’ve reached, what kind of a community can I really be part of?”

And a few years later, he remarked. He wrote to me, he said he is spending a lot of his free time in a yeshiva. He did not grow up in the kind of yeshiva that I grew up in. So he had to take whatever’s in the neighborhood. And he’s coming with serious questions on Gemara and Tanakh, and they’re giving him pep talks. And not really getting down and working. They’re talking how proud they are, that they are getting down and working, but there’s much more pep talk than actual production. What you can say in that case, go out there, learn from whoever you can learn from.

And remember, I’m including in this people that I’ve never, were dead, gedolim who are not around. People who have been dead for hundreds of years. And remember, I’m including people outside of the frum world. I mean, people tell me Ate Salid was an antisemite. I know that, but I learned from him. You know, Samuel Johnson, Kierkegaard may have been eccentric in his own ways, but these are people that I’ve lived with.

Now, the question that you’d ask further is, what happens if people don’t have that opportunity? One problem, what if they don’t have the background in Torah? And this haunts me because I can’t fully relate to that. Because when I was at that stage, I had the background. I could go to an advanced shiur, I could relate to the best rosh yeshiva. And I could even relate to them if they only spoke Yiddish. I had those tools, the tools in philosophy and literature and so on. Eventually, it was not that hard for me to pick that up. I was willing to put in the time and, but I had those opportunities.

What if you don’t have that? What if you’re a very bright person? You don’t have the skills in Torah. You may end up sitting in a shiur where most of the people have no sense of what you’re thinking about. And even the maggid shiur may not really fit you in terms of your sheer ability to think, and to question. When I wrote about this, well, we have Zoom, we’ve got all these other opportunities. And there are people who pick up email. There are times I really got a lot of people keep writing to me with personal matters.

And there are times when I don’t get those notes. There’s cycles in that. But there’s certainly people who are not embarrassed. And the people write me very often write other people as well. My dear friend Yaakov Elman, zikhrono livrakha.

David Bashevkin:

My rebbe.

Shalom Carmy:

We would almost know that if this guy wrote to me, he must have written to Elman as well. And on one occasion, I sent my response to a third person, taking out the reference of anything personal –

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Shalom Carmy:

… reference sent to a third person. And that person wrote back, “And here is what I wrote to So-and-so.” So there people are not, sometimes they’re nudniks, but very often they’re serious people. So they can pick that up, but it still is difficult. And then you can get annoyed. If you’re with people. For that, I am really not good at that. When I was young, I could be very cynical. People are that way. Whatever doubts they have about themselves, they project onto other people. You know it, I know it, and maybe less so today, but I have a good memory.

And at somewhere you have to make an effort, be autobiographical. Now we could do that at great length, but to save time, quote, one person, they gained a lot. His name was Rabbi Norman Frimer. His sons, have my best, and were still around, they’re productive people. And Rabbi Frimer used to tell me, “Do you realize that the people you’re looking at are cripples?” And he said, “It’s not just the Holocaust, not just the Holocaust. It’s usually dismissed things. They came to an alien culture. They came without intellectual tools. They had to adjust in a very alien world.”

I have said sometimes to non-Jewish audiences, where there’s similar fatigue, among my Christian friends as well. And sometimes I’ve said, “You realize that the world that I inhabit now. Look, my father got here early before World War I. But, most of us in the rabbinical world reached United States late. Many of them were physically broken. Many of them had lost their families. Even the one with the doctorate from the University of Berlin had to learn English, and had to learn United States from scratch.” And these people had the courage, or to use the Rav’s daughter’s term, the emunah, to come here and to do things. I mean the Rav started Maimonides at a point where the idea of not sending your children to public school was kefira.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Shalom Carmy:

It was unacceptable. This was the only road to Americanization. That he opened a kollel for European guys who could handle his shiurim.

David Bashevkin:

Okay.

Shalom Carmy:

Other people could do that also. But to make that experiment, it’s amazing. So, where we are now, compared to where you were in the 1940s, people would very well say we’re much better off than we were in the 1940s. And it might be total self deception. Where we go from here, I don’t know. Again, we talked about the people who are motivated, but they don’t have the same opportunities that I had, that other people had in my circles.

What we do next, how much of a community is there for the kind of class that I’m trying to give in variety of areas? Maybe a lot of disappointments. I mean, a lot of frustration. I give a shiur to balabatim. Sometimes if people are prepared, and they’re on you.

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Shalom Carmy:

Very often. If people you’re lucky, if they understand what’s bothering me, and you see that they understand what’s bothering me, if they can ask a good question afterwards. But, you don’t know if they understand what the other part of what I’m presenting is. But it’s not purely a religious issue. It also has to do with the people’s ability to concentrate, the ability to do discipline work. And my colleagues at other universities are complaining as well. You’re saying that the Zoom interlude destroyed any kind of ability to think clearly. And it may be that there are other factors as well, but that’s the world that we’re in. There are rabbanim who achieve a lot under those conditions. I don’t think that I would. I hope that I’ve accomplished something in Yeshiva.

David Bashevkin:

No, I think you accomplished a tremendous amount. I’m curious, when you look now towards the Orthodox world, where do you find experiential nourishment? Where do you turn? A lot of your response focused on the past? I’m curious where you turn in the present moment to nourish yourself?

Shalom Carmy:

My students are, they may not have that much experience, but some of them reflect intelligence and enthusiasm, and sometimes maturity. That means a lot.

David Bashevkin:

I wanted to kind of come back to the larger project, maybe the cause that you are trying to achieve. When you look at the issues facing religious life, religious conviction, there are a lot of darts that are thrown, and there’s almost, it’s almost a cyclicality. You know, I mentioned in our opening Biblical criticism, there are issues now that relate to morality, particularly in the moment, and how we think about it, consider the LGBT community in light of halachic restrictions. There’s always going to be people who are bothered by theodicy and the question of how bad things could happen to good people in the presence of evil in the world.

There are all these different categories, nearly all of which that you have contributed or addressed in one way or another of the history. What issue, facing religious conviction, which of these darts do you find the most concerning, and that the most work still needs to be done in order to address people who are grappling with faith in the modern world?

Shalom Carmy:

When I was a teenager, I would say theodicy, that’s an issue that you can’t simply turn your back on. Oh, very. You talk about Biblical criticism. So, there are people whose business it is to know about these things. If anybody wants to study Tanakh seriously, there’s a point where they consciously or unconsciously will be dealing with these problems.

I don’t know if you should call them problems, even, with these, with data that may deserve to be looked at seriously. Does that bother me, that say majority of the people who hear me discuss Chumash at shalosh sheudis don’t realize that sometimes I’m playing with these considerations as well. I once wrote an article on Vayikra which had no reference to the criticism at all. Yaakov Elman glanced at it, and he said, “Well, you solved this problem, but you didn’t really contribute anything on that issue.” But not everybody thinks that way.

The question of evil, suffering is something that you can’t really avoid. For somebody to say, “Well, God’s in his heaven. All is right through the world,” is not correct. The kind of story, things that you hear sometimes when people are sitting shiva, are either ridiculous or insulting. So there, I think it’s important for people, it’s not a challenge to people living religious lives, at least formally, but in terms of depth, if you cannot take that into account, you cannot absorb that kind of insight, you can’t live in that kind of world. There’s something missing. And something you can’t solve in one fell swoop. You sit down, you’re sitting shiva and read 10 perekim of Moreh Nevukhim. Even if you read those perekim with the Rav’s interpretation and my interpretation, that’s not the end of the story. It’s only beginning.

That really leads me to so-called moral issues. I think very specifically about the homosexual question. You have to begin by recognizing that the frum community, to a very large extent, I’ve heard nonsense in this for many years.

David Bashevkin:

What do you mean by that?

Shalom Carmy:

The idea of reparative therapy. Even if you’re a big believer in psychotherapy, the idea that a small number of clinical psychologists have hit upon some way of transforming people, that doesn’t make sense to anybody else, you realize that either this was giving people false hope, or as one of my colleagues, who is no longer alive, put it to me, “It’s wasting people’s money.” Either one is bad thing. And the allowance that was given to certain kinds of pejorative statements. It lowered the people who made the comments, and, I can only imagine the impact that it had on people for whom this was a real question, either for themselves or for people close to them.

Now I have, picking an issue where at one time I was, I viewed myself being very liberal. And now I’m apparently very benighted, but I haven’t moved. If I tie this to the previous point, it goes back to the question of theodicy at a certain level. It’s a whole different conversation, now. But if your theodicy is that God’s in his heaven, and one size fits all, and we’re all in the same rollercoaster. Then if there’s somebody who doesn’t fit, where somebody’s called upon to sacrifice or to achieve things with great difficulty. To fail at certain things, professionally or personally. Then that person is an outsider. That person has been shifted to the outside circle. If you have a conception of hashgacha pratit, which is essential again, if we go back to theodicy, then you have a personal destiny of God. You have your unique situation.

As the Rav liked to put it, “Every person has your own shade of color that they have to add to the world.” If you think in those terms, then your way of thinking about these matters is going to be completely different. The question, again, is what if you have somebody who is within religious community, but has not thought about hashgacha that way. That’s where the philosophical therapy has to begin. What if you’re dealing with people who have been given a very opposing and very insulting model of thinking about themselves, or thinking about people close to them? That is again a very serious problem. And again, the notion of hashgacha pratit, where you sit around saying, “Isn’t it wonderful that on 9-11, I had a headache that morning and I didn’t go to work. And isn’t it wonderful that my mother-in-law did not have a headache, and she did go to the World Trade Center that day.” That’s a stupid way of thinking.

So, there’s a balance here between this more populist idea of hashgacha and an idea where we live, we and the Ribono Shel Olam are together, and we have to make sense out of this, and thinking as we speak. A woman, not at all religious and conventional sense of the word, which is a member of ethical culture, blind from birth, achieved a great deal in her life. And was an authority on disability issues and other similar matters. She was dying of cancer, and we spent a few hours together. And she spoke about how her life plan had included marriage and children, and how she saw it was not going to work out that way. Included other things. Which side by side, with all the things she did achieve. There were the things that didn’t go the way she wanted to. And we spent hours discussing how such experiences would appear different to a person who believes in God in a more traditional way, or somebody who does not. That was a very serious conversation.

And I think would be important. We could take, we take ourselves seriously, and also have a sense of humor about ourselves. I think we take God much more seriously as well.

David Bashevkin:

I cannot thank you enough. There is something so deeply moving and I love that term, “philosophically therapeutic,” about speaking with you and reading your words. I always end my interview with more rapid fire questions. So you can condense your answer to these. These are kind of –

Shalom Carmy:

And I should thank you all the wonderful praise, but, as my cousin once said to me at a dinner where he was being honored, he sent me a note. He said, “No, that on these occasions, people don’t always say everything that they need. And they don’t mean everything that they say.” Okay, please, continue.

David Bashevkin:

We’ll leave that to our listeners to figure out, but I do mean it. My rapid fire questions, I always have three, my first question, and you can answer this, we don’t need the entire library. But aside from the books that we’ve already mentioned, if someone is coming to you and is looking to find a way to anchor their faith in something more real, to figure out how to ground their faith, what are your favorite books to recommend people who are grappling with these issues?

Shalom Carmy:

Again, I’m biased in terms of the Rav, in terms of Aharon Lichtenstein.

David Bashevkin:

Sure, sure.

Shalom Carmy:

And, Lichtenstein I really don’t know is written work that well. Because I heard it all –

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Shalom Carmy:

… in a draft. So, I’m not a, I’d say there is a lot that you can learn from some like C.S. Lewis. There’s a lot of common sense that you can get from some like Chesterson. And, these are things that are light reading, they’re not demanding. And Chesterson’s case you have to look away from antisemitism. I think there are, I think, novels that force a person to think seriously about moral issues and the like.

David Bashevkin:

What’s a novel that you would recommend? We don’t get so much fiction recommendations. I think it would be wonderful to hear a novel that has prompted you to think religiously.

Shalom Carmy:

I’m not going to say religiously, but George Eliot.

David Bashevkin:

Okay. Who –

Shalom Carmy:

Was raised very seriously religiously and it never quite left her. Virginia Wolfe said that “Middlemarch” was one of the few novels written for adults. And it was thinking about moral issues and being sensitive to moral issues. It’s very important. And it’s not the only thing that people should be reading, but, it shows you a mind working, who was very careful about these kinds of matters. There are a lot of insights, and if you want to go back to the beginning, the Chumash and Rashi, Chumash and Ramban.

David Bashevkin:

Sure, sure.

Shalom Carmy:

But I think that could be cheating, in this context, that could be cheating.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. Well, not necessarily. I remember when I asked, I had an interview recently with Dr. Haym Soloveitchik, the Rav’s son, who I’m sure, you know well, and I asked him for a book recommendation for understanding the Talmud better and he recommended the Rif. He said that that’s the best way to do it. So that’s similar to recommending the classic, “Chumash Rashi.”

My next question, I always ask our guests and this is actually a two parter. I usually ask one part, but I’m curious if you’ll answer the second part. I always ask my guests, if somebody gave you a great deal of money and allowed you to take a sabbatical to go back to school and get a PhD, what would the subject and title of that PhD be? And my part two for you, which is unique to you, is that what’s always intrigued me is that you have always been in the university, but never pursued an actual PhD. So I’m curious if you could A, say, if you were to go back and write a PhD, what would it be on? And, why is it that you never decided to get a PhD?

Shalom Carmy:

Well I had all the credits, and I was not yet busy doing everything I was doing. I figured I may as well get the credits and that way I had the freedom to either go ahead or not go ahead. So credits still there.

David Bashevkin:

Which school were you in?

Shalom Carmy:

I was at City in philosophy, at the graduate center, and in Revel, I was doing Jewish philosophy.

David Bashevkin:

Okay.

Shalom Carmy:

And I had the credits, but …

David Bashevkin:

Oh, I, your ability to finish a PhD is not suspect. I hope that’s clear.

Shalom Carmy:

I was busy doing the things that I wanted to do, which would require a breadth that would not be available within the normal academic world. And would involve a willingness to be very open about religious issues in a way that I don’t think is common. I know that in Rav Lichtenstein’s doctorate, there’s one place where he says very openly, “People for whom religious considerations, et cetera, et cetera, and I count myself one of them,” he was out in the open.

But, normally you know though that there are impediments to doing that. It was more important for me to move ahead, doing the things that I thought were important. Presumably, if I were, at the time, you see the thing is I really don’t know what I would do. And one possibility, do something in Talmud, I think I’m interested enough in the intersection of yeshivishe learning and academic Talmud. So I think all the arguments that I had with Yaakov Elman for 35 years and do something with it.

The other level in a completely different way, I could sit down and want to study economics because I feel that there, my knowledge is secondhand. And, if I really knew it from the bottom up, the way somebody who knows it, who’s studying it professionally, it would help me in batra, that would help me in other areas.

And I have been an affiliated scholar at Cardozo Law School, it would help me there. So that would be an option. Or get a law degree and function as a full-time expert on philosophy of law and halacha in general law. I don’t see that those are things are going to happen.

David Bashevkin:

No, and I’m so glad that you continued writing and contributing in the way you did. My last question, I’m always curious about people’s schedules. And I always wonder, what time do you go to sleep at night? And what time do you wake up in the morning?

Shalom Carmy:

Simple answer. When I’m tired, I sleep, when I’m not tired, I’m awake. It’s varied over the years. Probably, later years. I wake up a lot earlier. Most of the time.

David Bashevkin:

What’s early? We love giving a data range.

Shalom Carmy:

If I wake up at five o’clock and I actually –

David Bashevkin:

Okay.

Shalom Carmy:

… get up and get going. And I’m asleep at, I’m tired at a certain point. Take a nap. Nap. If the nap turns out to take too long, then it ends up being a night’s sleep.

David Bashevkin:

I love that answer.

Shalom Carmy:

I take a very casual attitude. I remember a doctor not too long ago was discussing certain issues with me. And, at certain point he said to me, “What I know about you, I don’t think you sleep too much.” And I said, “You’re right, but not quite as right as you think you are.”

When I was young, I trained myself to sleep very little. That faded away. What I benefited a lot from that, is waking up quickly and falling asleep quickly. And that has been, help halachically in terms of the years. My mother was –

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Shalom Carmy:

… needed help at night, that if she called out, I would wake up quickly. And if I didn’t wake up quickly, she a bicycle horn and –

David Bashevkin:

Ah.

Shalom Carmy:

That got it.

David Bashevkin:

That’s very sweet. Rabbi Carmy, I cannot thank you enough for your time and insight today. And for all of your work and contributions to Jewish thought, religious thought over the years. It has been a distinct honor, privilege, and pleasure to speak with you today. Thank you so very much.

Shalom Carmy:

My pleasure, and, please again, forgive me for not responding to all the nice statements, because again, I assume that they reflect more, what you want to be true than they actually achieves.

David Bashevkin:

Rev Shalom Carmy is not your typical inspirational speaker. He speaks with great deliberateness and pause. And really listening to him for me was an exercise, and nourishing, a nourishing exercise in yirat shamayim itself. In somebody who’s really committed their life to finding foundations, and uncovering and building foundations for faith, for his students, for his readers, and it’s really such a pleasure to have spoken with him.

In that final editor’s note, which we spoke about in the conversation, which is called “Lost Cause: A Conclusion in Which Nothing is Concluded,” he ends with a really beautiful anecdote that I think relates to a lot of the work that we’re doing on 18Forty. Again, this is his final editor’s note when he was serving as editor in chief of Tradition, and he wrote his follows.

“My editorial involvement in Tradition began before I joined the board in 1979. Several years earlier, the Rav invited me and he’s referring to Rabbi Soloveitchik, of course, of the rosh yeshiva in Yeshiva University, invited me to assist him in preparing some of his writings for publication.

The first installment was the special edition of five Tradition articles that appeared in 1978. This series included the Rav’s eulogy of the Talne Rebbetzin, in which he depicted the dual aspect of our religious tradition, the essential role of the Jewish father and the Jewish mother. A few months later, the Rav handed me a letter. He received his correspondent, had read the article carefully and appreciatively.

What replacement, however, could the Rav propose for people who do not have the benefit of the ideal father and the ideal mother who the Rav so eloquently extolled? We spent some time weighing possible responses. None of which the Rev found satisfactory. Did the Rav intend to write back? No, because he didn’t have a good answer. In that case, I asked, why did he give me the letter? The Rav looked at me in the eye and said, very deliberately, “Carmy, I want you to think about this.”

This anecdote adds one more ingredient to the profile of the Jewish thinker, adumbrated above in this article. He or she must not only articulate Jewish convictions, insights, and arguments, but must also be sensitive to the questions for which we do not have clear cut solutions. This is as true for the septuagenarian as it is for the young student.

And what a beautiful ending, so to speak, a conclusion in which nothing is concluded, the sensitivities needed to answer questions for which we do not have clear cut solutions. And I think in our return to rationality, I think this is an appropriate description. Because I don’t know that we’ve provided any clear cut solutions more than emphasized the fact that we as a community of listeners, a community of people, of individuals, are all grappling with something similar in trying to find some path on which to ground our lives.

And I think in this way, what Rabbi Carmy, at least for me represents, is somebody who is willing to really roll up their sleeves and figure it out and do the work to build a sanctified, sophisticated religious life and shows us that it can in fact be possible. And I want to end with one quote that I’ve used a few times, but it’s also from Rabbi Carmy, and I always come back to it, because I think we live in an age and an era where it’s too easy, unfortunately, not to embody. It’s an article that talks about how we learn Chumash how we learn Tanakh, how we study the Torah, and some of the ways in which we superimpose psychological explanations for some Biblical characters.

Now, Rav Carmy is not entirely against that, but he does have some pushback. And I want to end our series on rationality with this pushback. “One reason that people shrink the larger than life, personalities of Tanakh to pop psychology size is that they are accustomed to treating themselves the same way. What characterizes pop psychology, casual, deterministic assumptions, cliche, depictions of emotion, a philosophy that cannot grasp the dramatic, absolute momentous solemnity of moral religious life. This is not the way I think of myself. It is not the way I think of you. It is not the way one should think about any human being created uniquely in the image of God. Once people see nothing wrong in entertaining, secular conceptions of themselves, once they take for moral and psychological insight, the tired idiom of the therapeutic. It’s no wonder that they are tone deaf to the grandeur of the avot and imahot.”

And I think this condemnation, obviously not on the enterprise of sophisticated psychology, but on this pop psychology and superimposing it on any personality that you can’t quite plum the depths to, is a fitting ending, in many ways, to our return to the explanation of rationality. And it’s important that we are able to approach ourselves, and our own thinking, and our own lives with what he calls the dramatic, absolute momentous solemnity of the moral religious life.

To appreciate, as he says, “the complexity and sophistication of the human narrative and the human journey.” And I think that when we reduce our religious lives to easy, bite size answers and easy bite size solutions that just get us to point A to point Z, so we could figure out and feel absolutely confident with the paths of our lives. We are reducing ourselves, in many ways, to those cliched depictions of emotion, and not grasping the dramatic, absolute momentous solemnity that are our lives, religious or otherwise.

So thank you so much for listening. This episode, like so many of our episodes, was edited by our team member and friend Denah Emerson. It wouldn’t be a Jewish podcast without a little bit of Jewish guilt. So if you enjoyed this episode, or any episode, please subscribe, rate, review. Tell your friends about it. You can also donate at 18forty.org/donate. It really helps us reach new listeners and continue putting out great content.

You could also leave us a voicemail with feedback or questions that we may play on a future episode. That number of course is 9 1 7 7 2 0 5 6 2 9. Once again, that’s 9 1 7 7 2 0 5 6 2 9. If you’d like to learn more about this topic, or some of the other great ones we’ve covered in the past, be sure to check out 18forty.org. That’s the number one, eight, followed by the word “forty” F O R T Y dot org, where you can also find videos, articles recommended readings, and weekly emails. Thank you so much for listening and stay curious, my friends.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Julia Senkfor & Cameron Berg: Does AI Have an Antisemitism Problem?

How can our generation understanding mysticism, philosophy, and suffering in today’s chaotic world?

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

What Garry Shandling’s Jewish Comedy Teaches About Purim

David Bashevkin speaks about the late, great comedian Garry Shalndling in honor of his 10th yahrzeit, which is this Purim.

podcast

Yehuda Geberer: What’s the History of the American Yeshiva World?

We speak with Yehuda Geberer about the history of the yeshiva world.

podcast

Aaron Kotler: Inside the Lakewood Yeshiva

We speak with Rabbi Aaron Kotler about the beginnings of the American yeshiva world.

podcast

Alex Edelman: Taking Comedy Seriously: Purim

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David is joined by comedian Alex Edelman for a special Purim discussion exploring the place of humor and levity in a world that often demands our solemnity.

podcast

The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

podcast

Micah Goodman: ‘I don’t want Gaza to become our Vietnam’

Micah Goodman doesn’t think Palestinian-Israeli peace will happen within his lifetime. But he’s still a hopeful person.

podcast

Pawel Maciejko: Sabbateanism and the Roots of Secular Judaism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to historian and professor Pawel Maciejko about the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, Sabbateanism, and the roots of Jewish secularism.

podcast

On Loss: A Spouse

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Josh Grajower – rabbi and educator – about the loss of his wife, as well as the loss that Tisha B’Av represents for the Jewish People.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

Anshel Pfeffer: ‘The idea that you’ll obliterate Hamas is as realistic as wanting to obliterate Chabad’

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu did not surprise Anshel Pfeffer over the last 17 months of war—and that’s the most disappointing part.

podcast

Bruce Feiler: The Stories That Bind Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to author Bruce Feiler about family narratives.

podcast

Modi Rosenfeld: A Serious Conversation About Comedy

In this special Purim episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we bring you a recording from our live event with the comedian Modi, for our annual discussion on humor.

podcast

When A Child Intermarries

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to a son who almost intermarried, the mother of a daughter who married a non-Jew, and Huvi and Brian, a couple whose intermarriage turned into a Jewish marriage—about intergenerational divergence in the context of intermarriage.

podcast

David Aaron: ‘I believe that the Divine is existence and infinitely more’

Rabbi David Aaron joins us to discuss ease, humanity, and the difference between men and women.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Benny Morris: ‘We should have taken Rafah at the start’

Leading Israeli historian Benny Morris answers 18 questions on Israel, including Gaza, Palestinian-Israeli peace prospects, morality, and so much more.

podcast

Netta Barak-Corren: ‘I hope that Gaza will see a day when it is no longer ruled by Hamas’

Israel is facing several existential crises—at least three, by Netta Barak-Corren’s account.

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

Michael Oren: ‘We are living in biblical times’

Israel is a heroic country, Michael Oren believes—but he concedes that it is a flawed heroic country.

podcast

Lizzy Savetsky: Becoming a Jewish Influencer and Israel Advocate

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Lizzy Savetsky, who went from a career in singing and fashion to being a Jewish activist and influencer, about her work advocating for Israel online.

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Yishai Fleisher: ‘Israel is not meant to be equal for all — it’s a nation-state’

Israel should prioritize its Jewish citizens, Yishai Fleisher says, because that’s what a nation-state does.

Recommended Articles

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

What is the Megillah’s Message for Jews of the Diaspora?

For some, Purim is the triumph of exile transformed. For others, it warns that exile can never replace the Land of Israel.

Essays

Ki Tisa: The Limits of Seeing God’s Face

We spend our lives searching for clarity. Parshat Ki Tisa suggests that the most meaningful encounters may happen precisely where clarity ends.

Essays

The American Yeshiva World: A Reading Guide

A guide to the essential books that tell the story—past and present—of the American yeshiva world and its inner life.

Essays

A Jew in the King’s Court: Dual Loyalty in the Book of Esther

The Book of Esther suggests that diaspora is not merely a temporary or anomalous state but an integral part of Jewish history…

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

How Orthodox Jews Are Sharing Torah Knowledge Across Denominations

Two programs are already bridging the Orthodox and non-Orthodox divide through the timeless tradition of chavruta learning.

Essays

Why We Need to Live With Radical Laughter This Purim

Brother Jorge asks: Can we laugh at God? We might answer: We can laugh with God.

Essays

How Jewish Communities Can Help Couples Going Through Divorce

Divorce often upends emotional and financial stability. A Jewish organization in Los Angeles offers a better way forward.

Essays

The Siddur Has a Lot of Prayers. Where Did They Come From?

Between early prayer books, kabbalistic additions, and the printing press, the siddur we have today is filled with prayers from across history.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

What Haredim Can Teach Us About Getting Off Our Smartphones

Kosher phones make calls and send texts. No Instagram, no TikTok, and no distractions. Maybe it’s time the world embraces them.

Essays

Judith Herman Is Giving Voice to Survivors

Dr. Judith Herman has spent her career helping those who are going through trauma, and has provided far-reaching insight into the field.

Essays

What the 18Forty Team is Reading This Adar