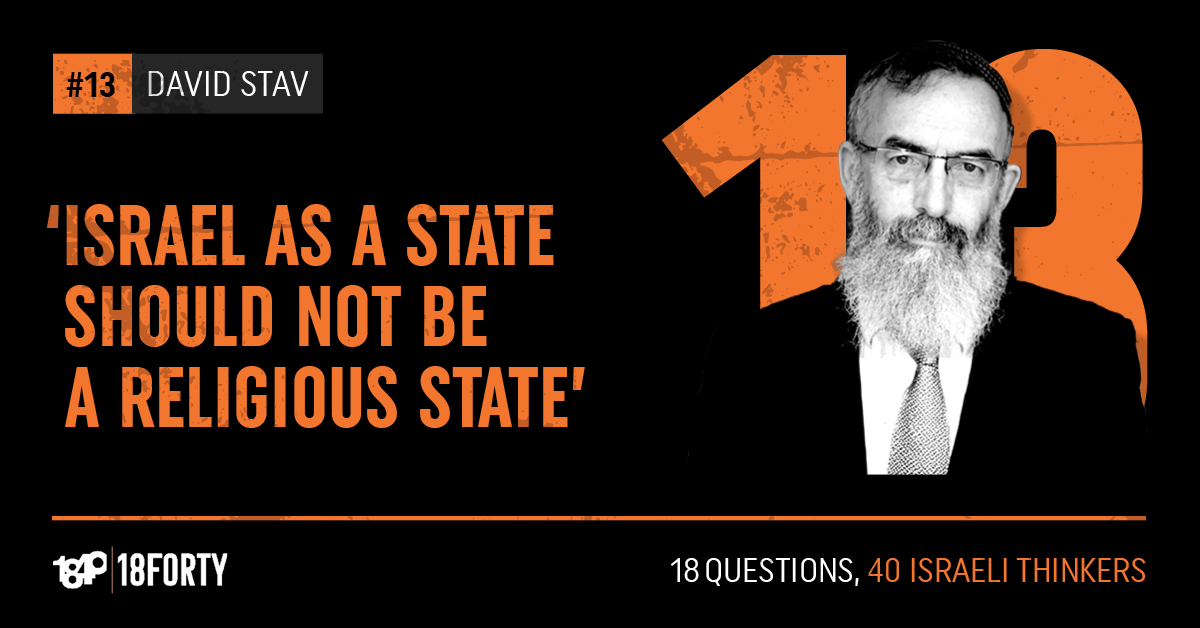

David Stav: ‘Israel as a state should not be a religious state’

David answers 18 questions on Israel, including Israel’s democratic character, the Haredi draft, and Messianism.

Summary

Israel should not be a religious state, Rabbi David Stav says, and then its citizens could more freely welcome religion into their lives.

The Chief Rabbi of Shoham — an Israeli town with a large secular populace — Rabbi Stav has long dedicated his life to bridging the social divides between religious and secular life in Israel. After the Rabin assassination, he and other rabbis founded Tzohar—an organization that “makes Jewish life accessible to secular Israelis—which received the 2009 Presidential Award for Volunteers.

Rabbi Stav was previously a candidate for Israel’s Chief Rabbinate and sought to revolutionize the relationship between religion and state.

Now, he joins us to answer 18 questions on Israel, including democracy, IDF drafts, and Messianism.

This interview was held on Sept. 11.

Here are our 18 questions:

- As an Israeli, and as a Jew, how are you feeling at this moment in Israeli history?

- What has been Israel’s greatest success and greatest mistake in its war against Hamas?

- How have your religious views changed since Oct. 7?

- What do you look for in deciding which Knesset party to vote for?

- Which is more important for Israel: Judaism or democracy?

- Should Israel treat its Jewish and non-Jewish citizens the same?

- Now that Israel already exists, what is the purpose of Zionism?

- Is opposing Zionism inherently antisemitic?

- Should Israel be a religious state?

- If you were making the case for Israel, where would you begin?

- Should all Israelis serve in the army?

- Can questioning the actions of Israel’s government and army — even in the context of this war — be a valid form of love and patriotism?

- What do you think is the most legitimate criticism leveled against Israel today?

- Do you think the State of Israel is part of the final redemption?

- Is Messianism helpful or harmful to Israel?

- Do you think peace between Israelis and Palestinians will happen within your lifetime?

- Where do you identify on Israel’s political and religious spectrum, and do you have friends on the “other side”?

- Do you have more hope or fear for Israel and the Jewish People?

Transcripts are lightly edited—please excuse any imperfections.

David Stav: Look, I’m a father of nine children, that all of them live in Israel. My 23 grandchildren live in Israel. I think I’ve never been in a doubt whether they will continue to live in Israel and if the Jewish state will survive. I grew up in ideology that that’s already the beginning of redemption and I still believe that it’s the beginning of redemption.

But for the first time in our history, I have questions that maybe our future is not guaranteed here. Shalom, I’m David Stav. I’m the chief rabbi of the city of Shoham and the chairman of the rabbinic organization Tzohar. And this is 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers from 18Forty.

Sruli Fruchter: From 18Forty, this is 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers and I’m your host, Sruli Fruchter. 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers is a new podcast that interviews Israel’s leading voices to explore those critical questions people are having today on Zionism, the Israel-Hamas war, democracy, morality, Judaism, peace, Israel’s future, and so much more. Every week we introduce you to fresh perspectives and challenging ideas about Israel from across the political spectrum that you won’t find anywhere else. So if you’re the kind of person who wants to learn, understand, and dive deeper into Israel, then join us on our journey as we pose 18 pressing questions to the 40 Israeli journalists, scholars, and religious thinkers you need to hear from today.

Today’s guest is Rabbi David Stav, the chief rabbi of the city of Shoham and the chairperson of Tzohar since 2009. There’s a lot of context and background that I want to give about Rav Stav that I think will help prepare you to deeply understand the interview and understand his perspectives and many of the different topics that we spoke about. What I liked about this kind of interview as opposed to some of the other ones that we usually do is that we focused a lot more on the domestic Israeli politics, realities, and religiosity that sometimes isn’t always spoken about when we’re taking a more of a macro view of Israel on the stage of the international arena. So I want to give a bit of background about Rav Stav because I think it’s very important to understand him and to understand where he’s coming from with his ideas.

The first place that we need to start is probably the most daunting to me, but it specifically relates to the interplay between religion and state in Israel’s government. Classically, a lot of us talk about how Israel is the only democracy in the Middle East, but of course as we know there is a deep rich Jewish character, Jewish religiosity, that doesn’t just live in the cultural reality of Israel but is also operative in the government function in the bureaucracy. And that specifically lies with the Rabbanut. I’m not going to try to embarrass myself by trying to untangle the very complicated web, as many people may know, of how the Rabbanut interplays and relates to the different parts of Israeli society, but in the most general sense, the Rabbanut oversees the various aspects of Jewish life in Israel, specifically as it relates to getting married, there is no civil marriage in Israel, getting divorced, burials, conversions, kashrut certification, who is and who is not a Jew in terms of immigration, the rabbinical courts.

So they have a hand in all of these things and in many of the cases have total control over them because that falls under their domain. Rav Stav is the founder or one of three founders for an organization called Tzohar, which following the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin in 1995, he along with Rabbi Yuval Churlo and Raffi Feurstein, probably mispronounced his name, and I think other rabbis, founded Tzohar as a counterweight to the Rabbanut, an organization that in their vision would help bridge the gaps and bridge the divides between secular Israeli society and the Rabbanut. Specifically, and this my understanding, I think even what they openly would say and as he indicates, try to compensate for the ways in which the Rabbanut in their view is failing Israeli society and secular Israeli society by the imposition of a stricter religious code and system. So Tzohar in their view is very much trying to diffuse the tension between the rabbinic establishment and the secular public in Israel.

They have different public policy initiatives regarding kashrut most famously, and there are a lot of legal maneuverings and considerations about what a restaurant can call itself as kosher because I believe the Rabbanut actually has ownership over a certain language about something being certified by halacha. And they also work with some other complicated formulas of trying to marry secular Israelis in a way that is accommodating to them and pleasing to them. In 2009, Rav Stav and Tzohar received the Presidential Award for Volunteers for their work. President Shimon Peres said, quote, it is important that the Jewish people draw pride and educational inspiration from your work and presented the award to Rav Stav, which I think is a pretty cool tidbit.

Rav Stav himself was also a candidate for the Chief Rabbi of Israel. There are two slots, a Sephardi and Ashkenazi slot. The Chief Rabbis also work with the Rabbanut. In his bid for Chief Rabbinate, Rav Stav had a much wider vision for revolutionizing how religion interplayed with Israel.

And we get into a lot of that in the interview, specifically when he’s talking about how religion ought to be delivered and related to Israeli society. And that, for Rabbi Stav, is a great opportunity to really try and live out this ideal that he has of bringing all of Israel together and all of Israeli society into the Jewish state in a way that meets people where they are and allows them to form their own unique relationships to Israel. One of the unique aspects about Israeli society is the way that there are so many different forces at play that are shaping the lives of Israeli people. It’s not just the politics, it’s not just the international considerations, and it’s not just the domestic realities and regular bureaucratic things of debates about economics, debates about taxes, and debates about social policy.

There is also the reality of religious policy and a religious influence and a religious force that is present in Israel. And that’s one of the things that I think differentiates this interview, specifically in how it gives light to those complicated factors. So, enough from me. Before we head off to Rabbi Stav, you probably already can guess what’s coming.

If you have questions you want us to ask or guests that you want us to feature, shoot us an email at info1840.org. We have gotten so many amazing suggestions, many of whom we are actually following up with and are scheduling interviews for in the meantime. So, if there are voices that you want us to hear, religious, secular, right, left, centrist, please let us know. And also, be sure to check out our site, 1840.org, 1-8-F-O-R-T-Y.org, for all things about Jewish life, Jewish questions, and being a Jew today.

And on a last note, if you can rate and review this podcast and share with a friend, it’ll really help us reach new listeners, and we really, really appreciate it. The video version of this episode will drop later this week. So, without further ado, here is 18 Questions with David Stav. So, we’ll begin where we always do.

As an Israeli and as a Jew, how are you feeling at this moment in Israeli history?

David Stav: A, I feel that we live in a very special, heroic history moment of the Israeli society, of the Jewish people, which could be compared only to amazing events in the Bible. B, I believe that we are in a kind of intersection that could lead us to disasters or could lead us to opportunities that will cause for our flourishing and developing of the society. But we are in a really challenging and historical moment.

Sruli Fruchter: I’m curious if you can share a little bit more about that.

Specifically, being not just a leader, but also being an Israeli, a Jew who’s here as well, how do you feel that your feelings differ in your leadership capacity and then also being a Jew here and an Israeli here like everyone else?

David Stav: Look, I’m a father of nine children. All of them live in Israel. My 23 grandchildren live in Israel. I think I’ve never been in a doubt whether they will continue to live in Israel and if the Jewish state will survive.

I grew up in ideology that that’s already the beginning of redemption. And I still believe that it’s the beginning of redemption. But for the first time in our history, I have questions that maybe our future is not guaranteed here. And just like we have went to exile after the destruction of two temples, it could happen again if we will not take care of ourselves and if we will not take the right decisions in order to guarantee our future.

Sruli Fruchter: What has been Israel’s greatest success and greatest mistake in the current war against Hamas?

David Stav: I think ‘s Israel’s greatest success was the fact that the spirit of our citizens, of our members of the big community, of the big congregation of the Israeli state, had such a high motivation to draft and to sacrifice their lives and to sacrifice their resources and their earning and their working just to guarantee and to help the future of our country. That was the biggest success. The fact that despite all the disputes and despite the crisis that was here after the judicial reform and all what happened before October 7th, despite all this, we managed to create a spirit yesh me’ayin, something from nothing. From a deficit, we created a huge positive power.

On the other side, that was the greatest mistake. The biggest mistake, I believe, of the Israeli leadership was that the leadership is dealing with politics, is not dealing with the society, doesn’t show any empathy, doesn’t take responsibility, doesn’t try to unify people, and instead tries to go back to its political original basis and sticking to the political position and to the chair and not doing all what’s needed to be done for the Israeli security.

Sruli Fruchter: Is there anything in particular that you’re thinking about when you talk about the Israeli leadership’s tendency to keep falling back into politics at this time?

David Stav: I think it’s clear leadership is the government. Leadership is the head of the government which runs the country.

I’m not saying that there are not other partners that should take part of this responsibility for what happened in October 7th, but the responsibility to unify the people is given to one person, and that’s the king. The person, the reason why we were demanded, according to the Rambam, to appoint upon ourselves a king is that we need somebody that will fight our fights, will judge us in a justice way, and will unify the Jewish people, the Jewish tribes. That’s the idea of establishing a kingdom. And the first and maybe the most important mission of a king is to unify people.

If a king does the opposite, it means that he fails in his biggest mission.

Sruli Fruchter: How have your religious views changed since October 7th?

David Stav: I wouldn’t say that the religious views changed, but the way I translate a few of my religious views, the way I translate it to practical behavior has been changed. So first of all, one thing which was changed is that I believed until October 7th that there is no question about our ability to overcome all the obstacles that are in front of us and all the external and internal threats that threaten our existence. Today I hope, I believe that Hashem will help us, but I’m not sure that we deserve such a help from Hashem.

That’s a religious view. A second behavior that has been changed is to try to deal less with the internal rabbinic politics that I’m familiar with and I’ve been dealing for years and less dedicate time for internal political rabbinic debates and do much more to reach out and to engage secular society to the Jewish roots and to the Jewish heritage more than dealing with our own bubble. What

Sruli Fruchter: do you look for in deciding which Knesset party to vote for?

David Stav: I think when I will have to take the decision to which party to vote, it will be led by one major issue, is this party thinks of what is good for Klal Yisrael, for the State of Israel, and will take every decision needed in order to improve what’s needed to the benefit for the state of Israel and not for its own sector and group in the Israeli society.

Sruli Fruchter: Which is more important for Israel, Judaism or democracy?

David Stav: I think the Judaism without democracy is not Judaism and I think the democracy without Judaism has no meaning, gives no meaning to live in the State of Israel.

To be in Israel and to be only democratic without understanding the Jewish roots and the importance of creating a Jewish identity and the Jewish nationality and a Jewish state, so if that’s the case there is no reason to live in Israel. To be Jewish and not to be democratic is to be something that takes from yourself the soul of Judaism. The ABC of Judaism is the freedom of choice. Torah is not coerced upon us, Torah is given to our decision and we are the ones that were writing a covenant with Hashem, with God in Mount Sinai, afterwards in Moav, and afterwards in the Land of Israel.

We were signing the covenant with Hashem. It requires our decision and Judaism without democracy is not Judaism.

Sruli Fruchter: I hear what you’re saying and I’ve heard people say that before as well but I’m curious, when Judaism and democracy seem to come into conflict, which of the two do you feel is more important, needs to be prioritized and you are more comfortable with letting go of the other?

David Stav: I don’t believe that there is one way to answer that question. By definition, the fact that I define myself as a part of a nation, it means that I give certain incentives to my family.

That’s not against the values of democracy. Although all people were born equal, all are born in the shape of God and God loves everybody, but nobody expects from me to write a will that all people in the world will take, each one of them will take half a penny of my properties and from my bank account. Everybody understands that I will give my properties and my goods to my descendants. The same thing applies when we talk about the Jewish state.

Of course, nobody expects that the Law of Return will apply to non-Jewish people, but somebody could perceive this as something which is anti-democratic. So if the definition of being Jewish or existing of a Jewish state means that the Law of Return will apply only to Jews and somebody will see this as anti-democratic, so then in that sense Judaism is overcoming and overtaking democracy. But if somebody will try to say in the name of Judaism that because Judaism requires and the Torah prohibits violating Shabbat or not observing Shabbat, as a result of that, we will coerce and we will force everybody to observe Shabbat in his home and if he will not, we will not let him live in Israel, so then democracy is overtaking Judaism. But as I said in the beginning, I really don’t believe that there is a contradiction.

I think that these two values are intertwined together. The problem sometimes of the rabbis is the lack of explaining why democracy and Judaism should live in coexistence and why it’s necessary to Judaism just as it’s necessary to democracy that these two values will coexist.

Sruli Fruchter: Why would you say that is, that it’s so important for them to coexist in the state of Israel?

David Stav: Because I believe that, as Rav Kook says and as others have written in their commentaries, Rav Hirsch and others, that God wants people to worship Him just if it comes from their own original heart. He does not want people to worship Him because they are terrified by natural forces, because they are afraid that if you will not worship Him in this way, something terrible will happen to them and that will be the main motivation for them to worship God.

I believe that God wants us, loves us, and wants us to partner with Him in improving the world, in creating a world of justice, of law, of morality. That’s the reason why He has chosen Avraham Avinu and that’s the reason why He has chosen the Jewish people. And if that’s the case, it could not be achieved and could not be accomplished if this society would be forced to do something. People that are coerced to do things could not be partners to nothing.

Sruli Fruchter: Should Israel treat its Jewish and non-Jewish citizens the same?

David Stav: Yes, very simple. The answer is yes. You asked me in the beginning to give answers between one to five minutes, so I can give it to you in half a minute. The answer is yes, as it applies to them as individuals.

As individuals, every man and woman are entitled to the same rights that Jewish men and women have. When it comes to national rights, there’s only one nation that has the right to self-definition here in the land of Israel, and that’s the Jewish people. That’s the homeland for the Jewish people and not for any other nation. But as individuals, the Druze and the Circassians and the Bedouins and the Muslims, Christians, whoever lives there has the right to live and to benefit the same rights.

Sruli Fruchter: So if someone were to say that elevating the national rights of one group of people is not holding up democracy in the way that I think usually in the West it’s understood, do you see that type of contradiction or where do you disagree with that type of assessment?

David Stav: Israel is the homeland of the Jewish people, and it’s a Jewish state by definition. If somebody thinks that to define a nation or to define a state or nationality, it’s anti-democratic, I think he’s wrong in understanding what is democracy. Democracy doesn’t mean that families lose their identity and nations give up their identity. I think democracy is about the rights of the individuals to freedom of speech, to freedom of work, to freedom of faith.

But it doesn’t mean that every state has to commit suicide and to give up its own identity. By the way, Rav Kook explains in one of his letters that this is the guidelines or that’s the line between democracy and committing suicide. Because the fact that I allow freedom of speech or freedom of faith doesn’t mean that I allow committing suicide. And that’s the boundaries.

If a community will allow people to express values that will call to self-destruction, then that’s not democracy. That’s a sick society that doesn’t want to protect itself. The boundaries of democracy and of freedom are when the definitions of democracy will threaten the existence of this identity by itself.

Sruli Fruchter: Now that Israel already exists, what’s the purpose of Zionism?

David Stav: For me, Zionism is in the first and foremost gathering Jews from all over the world to the Land of Israel.

So half of the mission has been completed. A half still live in other places. As a matter of fact, this podcast probably will be broadcasted for people that could be the Zionists in their heart, in their soul, but they’re not yet implementing it in real. But that’s only the first part of Zionism, to create a safe shelter for the Jewish people and to bring the Jews to the Land of Israel.

And I believe that the second part of our mission is the mission that is mentioned in the Torah. You shall become a kingdom of priests and a sanctuary nation and a sanctified nation. We are still in the beginning. We’re not there yet.

We have to establish a society of justice, of law, of welfare, a society that will be able to show all nations in the world, give a look at us, that’s the role model, how society could look like. We’re not there yet.

Sruli Fruchter: Is opposing Zionism inherently antisemetic?

David Stav: You know, there’s a famous speech of Rabbi Sacks that was given a few years ago, that antisemitism dresses up in different dresses during history. Sometimes they are against Jews that try to integrate with secular people or with Gentiles.

Sometimes it was against Jews that were segregating themselves. Sometimes it was because Jews lived with us. Sometimes it’s because Jews live somewhere else. I believe that everybody that is anti-Zionist is antisemitic, but it’s in a different dress.

Sruli Fruchter: How does that view change for you, if at all, when thinking about religious anti-Zionists, primarily from the more of the Yeshivish or the Haredi world, or non-Zionists perhaps, non or anti-Zionist, because there is that spectrum?

David Stav: I would say the following. If somebody would say, I’m anti the political movement of the Zionist movement because it is secular and it pushes people from being frum to be not frum, I could understand that very specific approach. But if somebody will say, I’m against Zionism because I’m against political entity for the Jewish people, but in essence, not just because they’re secular or not. So that is anti-God.

You cannot be Jewish, of course not observant Jewish, and to be against the Jewish people. There is no meaning for being religious as an individual. The Jewish religion was not given to individuals. It was given only to whoever who feels himself a part of a nation.

As we all say in the morning, when we say, when we recite the blessings of the Torah, He has chosen us. He has picked us out of all the nations and he has given us the Torah. He did not give us the Torah as individuals. There is no value of observing Torah as an individual.

I had somebody, many years ago, 30 years ago, a woman that wanted to convert. And she said, I asked her where is she going to live? She mentioned the name of a place in England where the closest Jewish community was 50 miles away from that place where they wanted to live. So I asked her, but you know, it’s very far from a Jewish community. And she said, well, actually the truth is that I don’t like Jewish people.

I don’t want to be with their environment. I said, look, to be a convert, there is no conversion without being in contact with the Jewish People. It’s a package deal because God has chosen the Jewish People to carry that mission and to be just Jewish, even if you were born as Jewish. And of course, if you are a convert, but even if you’re born Jewish, to be Jewish and to be against the Jewish People, meaning it’s not Judaism, it’s not Jewish religion, it’s not Jewish nationality, it’s nothing.

Sruli Fruchter: So it’s actually very interesting. I’m just thinking of this now, but I know that a lot of what you’ve spoken about and what you do with Tzohar and what you do in Shoham and a lot of the work that you advocate for is, and you mentioned this earlier, is that outreach of unification for not just the Dati Leumi, the Religious Zionist Jews or the Jews within more of an Orthodox circle, but even the Jews beyond that. In America, it’s probably in some form in Israel as well, but in America, there’s definitely a much greater rise of anti-Zionist Jews who are secular, they’re not Haredi, on college campuses, with a whole different set of considerations. I’m curious from the approach that you’ve taken for unifying or reaching out to a lot of the Jews in Israel, a lot of the secular Jews in Israel, the Hilonim, how you view that type of consideration given a new wave that we’re seeing, which doesn’t seem like it’ll end when Hamas ends.

David Stav: Well, I think that in America, we face a very, very deep problem. Before I refer directly to your question of millions of Jews that have lost any connection to Judaism, it’s not only by marrying out, which is a part of the symptoms of that phenomenon, but it’s also, we see this in the numbers of people that are connected to all denominations, including the Reform and Conservative denominations, that we see that less and less Jews are connected to these denominations, which means that more and more Jews show less and less interest in being connected to the Jewish people altogether. Forget the State of Israel. I believe that the main reason for that is because when the American Jew, when he arrives to the age of 12 to 18, 20, and he goes to the university and he asks himself, what does it mean for me to be Jewish? I’m not observing Shabbat, I’m not observing kashrut, I don’t think that the Jewish people are different than others.

It has no relevancy to me, it doesn’t make any difference for me, so why should I stay Jewish? And since he has no meaning, and he doesn’t find any meaning in his Jewish identity, so then what’s wrong with assimilating and marrying out? All this is true before we started to say a word about the Zionism and the State of Israel. Add to that that he hears from his friends that the Jewish people are so terrible, they’re doing so many bad things to the Arabs and to the Palestininians, so then he says to himself, oh, not only that I never found a positive meaning in being connected to the Jewish people, now I have a negative reason why not to connect myself, and then he feels again that he has no reason to connect himself to what’s going on in Israel and to Judaism altogether. I really believe that it has to be changed, but I refer to all these students as what we call Tinokot Shenishbu, kids that were kidnapped. That’s kidnapped by culture, kidnapped by the atmosphere where they live, by the climate, by the social cultural climate that they live in. I don’t blame them.

For me, they are kidnapped children. I blame myself and I blame ourselves for not educating them, for not giving them an added value for what does it mean to be Jewish? What is the historical mission that we carry upon ourselves since the time Torah was given to us? What did we do good for the world and what else should we do in the future for the good of the world, for the benefit of the world? I believe that these people never heard about the values that the Jewish people contributed to the Western culture, to the existence of this world, and as long as people don’t find any positive meaning in connected and engaging to Judaism, I don’t think that Zionism is their main problem. I think it begins somewhere very, very early in their lives in something which is much more fundamental than dealing with the question whether from the river to the sea is the solution or not. We are far, far in the distance from that question because they have to understand what is Judaism altogether.

Sruli Fruchter: Should Israel be a religious state?

David Stav: No.

Sruli Fruchter: Can you say more?

David Stav: Yes. Israel should be a state for the Jewish people. If the Jewish people will be observant, religious, so Israel will be a religious state.

If the Jews in Israel will not be religious, it will not be a religious state. It should always remain a Jewish state and leave the issues of observance, of practicing to the individuals. Israel as a state should not be a religious state.

Sruli Fruchter: I’m curious if you can talk about how you understand that, I guess, on two fronts.

One is, I think that for many people, whenever they’re, you know, they’re Dati, they’re religious, and they’re trying to think about the vision of Medinat Israel, of the State of Israel, and what it means today, the question of halakha, of Jewish law, definitely is on their mind and what that will look like. You know, Rav Herzog wrote about that, Rav Goren, and there’s different things in that regard. So I’m curious, A, on that front, how you view the halakhic dimension of what relevance that should have to a state, and then also in your role with Tzohar and having previously run for the chief rabbinate, how you understand all of those things.

David Stav: Well, this could be a class for 45 minutes.

Sruli Fruchter: No, that’s our problem. All these questions could be a podcast. But this is

David Stav: specific, because you’re asking a Halakhic question, which is basically as to deal with a few halakhic topics that are mentioned in the Gemara, in the Talmud, in which we get the impression that basically, in a Jewish state, there should be a religious coercion. As a matter of fact, the Talmud says that if somebody doesn’t obey to certain rules in halakha, meaning we should hit him until he dies, if he doesn’t, if he refuses.

I guess that none of us wants to live in a country where if somebody would get up late after the Zman of Kriyat Shema, which is a mitzvah to say, a positive command from God to do, you don’t want a father to hit his son up till death, till death, if he refuses to get up in the morning when he, if he came back late from Bnei Akiva or from the club or wherever he went you don’t want his father to hit him to death. But the question is, okay, I don’t want it, but if that’s what the Talmud demands, if that’s what the Torah demands. So this, that’s why I said it requires a bigger discussion, but I will summarize it in one sentence. There’s a difference between society that’s run by Torah laws when, A, the people were accepting upon themselves the rules of Torah as the rules which will dictate their lives, and a society that never accepted it upon itself.

Now, if the society will accept upon itself that they want parents to hit their kids to death in order to read, to recite Kriyat Shema, okay, that’s fine. As long as people are not ready to do that, the Torah doesn’t demand us to do that. A. B, I believe that there is a big difference between societies that lived in time when the only way to dictate rules was by showing power and by coercion versus our period in mankind history that we understand that today the way to talk to people is not by hitting them, is not by coercing them, but by convincing them.

And therefore, Rav Kook says that in this generation, we don’t coerce. In this generation, we talk. We talk, we inspire, we embrace, we never coerce. And that’s my approach to the Jewish state.

Now, having said that, in Tzohar, what we try to do in all areas, in all dimensions of life is to expose, expose people to what there is in their heritage. You can choose, take it or leave it.

Sruli Fruchter: Very briefly, before you explain Tzohar, can you, like, in one or two sentences, just give a snapshot for people who aren’t familiar with how the Rabbanut operates in regards to Israel, what they do or don’t have control over?

David Stav: Well, you have to understand that in Israel, unlike America, there is no civil marriage. And the only way to get married in Israel is through the Rabbanut.

You can get married in Cyprus, and that’s what tens of thousands of Israelis do. But if you want to get married in Israel, it’s only through the Rabbanut. Now, without criticizing the Rabbanut, it’s just natural that a monopoly refers to itself as a monopoly. Just like, you know, when you travel in an aircraft, the airline will say, we really know that you have different options to fly, and we appreciate you flying with us in EL AL or United or Delta or somebody else.

And they will always try to improve the customer service because they know that we, the passengers, we have options. We can choose. In Israel, there was no way to choose. And once you don’t have freedom of choice, it ruins up the system because then the monopoly never tries to improve itself.

And that’s exactly what happens to the marriages in Israel. And the couples voted in the field. They went to Cyprus or decided whatever they will do, they will not get married in the Rabbanut. And that’s started 28 years ago to establish our services in marriage.

But we are already far away from marriages alone. We are doing a lot of projects, which, if I will summarize, what we do is to expose secular Israelis to Judaism in a nonjudgmental way and in a way that offers without any attempt to make people frum just to expose them. So we are now, I don’t know when this program podcast will be broadcasted, but we’re now a few weeks before Yom Kippur. Yom Kippur last year, we had more than 600 locations of people that came to pray with us.

We intend this year to do this as well. I think one of the central prayers in Tel Aviv, in the hostages square will be with Tzohar. And people say, and say to us and say to others, if not for Tzohar, that gives us the freedom to choose whether we want to come or don’t want to come. If not for Tzohar, we would never go to a shul on Yom Kippur.

And I think that approach proves itself. And I wish we could copy that to the entire state, that the state will be offering and not and not imposing, because I believe that we pay a huge price in antagonism and hatred and ignorance of the Israeli society that doesn’t want to be imposed, doesn’t want to be coerced. And therefore, as a response to the attempts of coercion, responses in a very antagonistic way and throws the baby with the dirty water, doesn’t want to study Tanakh, doesn’t want to study Jewish heritage, doesn’t know what’s Birkat Hamazon and what’s siddur, as we can find hundreds of thousands of ignorant Israelis. And the reason for that is because once you try to control them or to coerce them, they will just react in the exactly opposite way.

Sruli Fruchter: If you were making the case for Israel, where would you begin?

David Stav: If I would make the case for Israel in the campuses, let’s say.

Sruli Fruchter: Um, yeah, in general, if you were how to make the case for Israel. I believe

David Stav: that I will start from the truth. And the truth is, where the Torah begins, that this land was promised to us by God through Avraham, Yitzhak and Yaakov.

That’s the truth. That’s where we begin. And we were taking, I would say the story, I would summarize the story of the Torah by the way, which is not denied by the Christians, which are a huge part of the world and basically is not denied by the Muslims as well. And that’s where I would start.

Unfortunately, almost none of our political representatives begins with that. Most of them start in 1948, the Holocaust. And since that’s the way they present the case, I could understand the arguments that the Palestinians will raise. Okay, so if that’s the reason, we believe that the decision of the United Nations was not fair, was not moral.

And we were here before you arrived, and we don’t have to suffer because you suffered in the Holocaust. And then it begins a kind of a political debate, which from my eyes is not the right debate. We are debating on a religious debate. Was this land given to us by God or not? And if we don’t say our position clearly, how could we think that others will accept our arguments?

Sruli Fruchter: Should all Israelis serve in the army?

David Stav: Yes, including yeshiva boys, if that’s the question.

After saying yes, I think we should ask different questions. Are the governments in Israel determined to draft all Israelis to army? And the answer is no. And that’s the problem. Because there is a big gap between the declaration that everybody has to go and the determination, which does not exist to do that.

Had their leadership determined to draft, they were drafted.

Sruli Fruchter: By the way, not which leadership you’re saying—

David Stav: Both from right and left.

Sruli Fruchter: You’re saying political or religious?

David Stav: Political. Political leadership.

Could be very easy. Today, the situation is that the government encourages Haredim not to go to the army. Encourage them not to go to the army.

Sruli Fruchter: Encourages them how?

David Stav: How? By subsidizing.

It doesn’t pay for a student to go to the army. It doesn’t pay to his society that he goes to the army. It doesn’t pay for him to go to work afterwards. Because the amount of money that the government pours on them, and it doesn’t, I’m not referring to the money for the yeshivot.

That’s the small amount of money. But the support in taxes in the municipalities, the support in taxes in the social security, in health care, all the indirect support that the government gives to those who do not go to the army arrives to sums of around $3,000 a month to a family. So why should he go to the army?

Sruli Fruchter: Many in the Haredi world, when people are discussing about the Haredi draft to the army, talk about and bring up that they believe Torah study is important and necessary for the war effort and for Israel.

David Stav: That was the argument.

But that’s not the reason. Because today-

Sruli Fruchter: Do you agree with that?

David Stav: No, I disagree with that on the halachik basis. But even if that’s true, that’s not the story. Because all governments were ready to release those who study Torah.

But the problem is that today 70% of the Haredi boys do not study in yeshivot. They just hang around. They go to do whatever they want. They don’t study.

And the rabbis strengthen them saying that the problem with going to the army is because you’ll become secular in the army, which I could understand them. I understand the argument. Torah studies was an excuse for certain years. That’s not the excuse today.

And I believe that there is also a political reason. I mean, it’s not only the concern. So there are one is the Torah, which is relevant to certain group. One is being secular, which is relevant to second group.

And I think that what summarized together—

Sruli Fruchter: What do you mean being secular? Oh, the concern of becoming secular.

David Stav: Becoming secular. And the third thing, which I believe is the most important one, is the concern to lose control on the people and to lose the political power you have.

Sruli Fruchter: Can you briefly elaborate? You mentioned before that on the point of Torah study, you disagree that it’s helpful for the war effort.

I’m curious if you can elaborate on that. And I’m also curious if you can take into consideration the Hesder yeshivot of the Dati Leumi world that integrate Torah study with army service. Do you view that differently and how that’s operated? Traditionally, people have understood it to mean that it’s the Torah study in addition with the physical combat or contribution to the army. I’m curious if you can elaborate.

David Stav: Two issues. One issue is, is studying Torah helping to the Jewish people? The answer is 100% yes. Torah studies help to the Jewish people. The Gemara says that in tens of places, but it’s clear if somebody’s doing mitzvah, by the way, not only Torah studies, if somebody’s giving charity, if somebody’s observing Shabbat, every Jew that is doing positive way and avoids himself from doing negative things is helping the general effort of the Jewish people.

That’s not a question. What can we do? There is a mitzvah. We have to observe what Hashem commands us. And Hashem commands us to go to the army and to fight certain wars.

There’s no release in the Torah for those who study Torah from going to the army. Just like there is no release for somebody who studies Torah from putting on tefillin and from davening. There is no release for somebody that studies Torah to take the four minim and Sukkot and to sit in the sukkah. And there is no release for somebody not to go to the army and to fight against those who want to kill us.

It’s milchemet mitzvah, as Rav Elyashiv wrote in several places, as the Chazon Ish mentions in several places. And there is no release for yeshiva boys from going to the army to fight the wars of God. The fights … the wars of Netanyahu. It’s the fight and the wars of the Jewish people.

And the fights of the Jewish people against the enemies that want to destroy us from the root is the fights of God. And we are commanded to fight the fights of God.

Sruli Fruchter: Can questioning the actions of Israel’s government and army, even in the context of this war, be considered a valid form of love and patriotism?

David Stav: I didn’t understand the question.

Sruli Fruchter: Can questioning the actions of the government and army, even as it relates to the war, can those things be considered a form of love and patriotism?

David Stav: People could criticize government and … I see myself as somebody that sometimes criticizes, sometimes compliments the government. I think everybody has the freedom to think and to say whatever he thinks about the behavior of the government. Sometimes it is perceived to be behaving in a proper way. Sometimes they are mistaken, just like every human being.

Sruli Fruchter: What do you think is the most legitimate criticism leveled against Israel today?

David Stav: As long as criticism is based on facts and as long as criticism is based on values that are implemented in other places under the same circumstances, it’s legitimate. It’s not legitimate to criticize Israel bombing civilian areas when the Americans in Afghanistan and Iraq were doing 10 times more and worse than that.

And that’s hypocritical criticism. It’s not legitimate. If somebody is behaving himself in not the proper way, a soldier is not doing the right thing to an Arab or to a Palestinian, he should be criticized. I expect for my army to be moral and I expect my government to be moral.

But I expect the criticizers of the government on morality, that they should use the same criteria to criticize us in their own activities.

Sruli Fruchter: Is there a specific type of criticism that you’ve heard that that’s usually leveled against Israel that you think that’s one of the more legitimate ones?

David Stav: Criticisms that were done, were said in Israel in different areas. Yes, it could be legitimate.

Sruli Fruchter: Is there an example that you’re thinking of?

David Stav: In moral issues or in political decisions? It’s not the same.

Your choice. In moral decisions, I believe that our government and our army is the most moral army in the world. And therefore, I didn’t find any criticism that was legitimate. When it comes to political decisions, I think that a lot of criticism was legitimate if people criticized the government for making the war too long because of political reasons.

Or this is a legitimate criticism. I don’t know if it’s true or not, but it’s a legitimate criticism. If people criticize them for not using, for not going into Rafah in the beginning of the war and waiting with the story of Philadelphi trail until now, that’s a legitimate criticism. Every criticism that is political is relevant.

If you criticize on moral basis, when you yourself don’t behave in a moral way, that’s not legitimate.

Sruli Fruchter: Do you think the State of Israel is part of the final redemption?

David Stav: Of course. Of course. Yes.

Yes. I believe that what has been achieved now is far above all of our expectations. All of our ancestors would have loved to live in our time. It’s far behind what the Prophets have described.

Having said that, it doesn’t mean that we’re not in danger. And all these achievements could not be risked and could not be in danger if we would not know how to behave ourselves.

Sruli Fruchter: I was going to actually ask about that because earlier in the interview, I forget which question it was when you were discussing about your fear of a third exile, of a third Churban destruction.

How do you see those two things relating? I know traditionally there was a lot of, I think from Rav Herzog and others have said that after there’s a third time we’re brought back to Israel, we had the first Beit HaMikdash, the second Beit HaMikdash, but the third time, that’s the time for real. And there won’t be such a concern.

David Stav: Look, I always believed in what Rav Herzog was saying and what was quoted in his name. And we heard this from Rav Kook as well.

But I never believed, despite the fact that I believed it in what they said, that God works for us or by us and we cannot dictate him how to run the world. And I guess if God forbid something bad will happen to the State of Israel, so then we’ll understand that what we had now is not the Third Temple. We’ll find ways to settle Rav Kook and Rav Herzog. But I believe that it’s given to us and God has given us an opportunity and he wants us to improve our ways and to make this redemption the final one.

But we have to work very hard for that.

Sruli Fruchter: Is messianism helpful or harmful to Israel?

David Stav: Depends what messianism is. If messianism means that you work and you are not afraid and you are determined to continue despite difficulties, so then it’s helpful. If messianism causes you to be arrogant to others, if messianism causes you to be not moral, if messianism causes you to be extreme, if messianism causes you to be somebody that doesn’t listen to the professionals in your office, etc., etc., so then it makes a huge damage.

Sruli Fruchter: Do you think peace between Israelis and Palestinians will happen within your lifetime?

David Stav: No.

Sruli Fruchter: Can you say more?

David Stav: Look, I believe that peace is a part of my vision. That’s the vision of the Prophets. But I’m also realistic and I know whom we deal with and until they will be deterred, there will not be peace.

And from what we have learned, if there is something we have learned in October 7th, is that our enemies are far from being deterred and it will take time until we will come back to our power in a way that our enemies will understand one and for good that we have no intention to leave that place. So far, we are very far from that. Many Israelis ask themselves if they want to live here and our enemies don’t need to defeat us physically. What they need is to defeat us morally and culturally and socially, just to create the understanding that here will always be bad.

And what do you need all this for? And there is no value in living here. Why do you need to fight all the time with your religious or secular neighbors? They just have to make the life in Israel miserable in order to achieve their meaning, their goal. So therefore, I don’t see peace in the near future.

Sruli Fruchter: Where do you identify on Israel’s political and religious spectrum? And do you have any friends on the other side?

David Stav: Politically, I am located in the right, politically.

Religiously, I guess I’m located in the center with a slight tendency to the left. Of course, I have friends from all sides, from the left in the politics and from the right in the religiously. Yes, I have friends from all sides.

Sruli Fruchter: Okay.

And for our last question, do you have more hope or fear for Israel and the Jewish People?

David Stav: No, we have a lot of hope. We don’t have the privilege to be desperate. We didn’t get that gift from God 76 years ago just that we will waste it and to mess it up. No, we don’t have the privilege to fear.

But I would lie to you if I would tell you that from time to time, I don’t get that feeling of fear of what’s going to happen to us. But what motivates me and what leads me and what I’m trying to convey to myself and to my counterparts and to my listeners and the audience that wherever I am is that we’re gifted with a huge gift of the State of Israel, of the Jewish people. And we have a big hope to strengthen and to go from strength to strength. And b’ezrat Hashem, we will overcome that challenge and the obstacles that have been rising in the last two years.

Sruli Fruchter: Okay, Rabbi Stav, thank you so much for answering our 18 questions. Anything that we didn’t ask that you think we should have?

David Stav: No, but I’m afraid it was much more than 18 or maybe I’m wrong.

Sruli Fruchter: There were a lot of follow-ups because a lot of interesting things that I wanted to I hope you weren’t counting.

David Stav: Thank you. Shalom, Shalom.

Sruli Fruchter: As usual, there is so much that’s left unsaid after one of these interviews, and I hope that gives us a launchpad to try and delve deeper into the topics that are brought up into Rabbi David Stav, into Tzohar, into the establishment, the rabbinic establishment in Israel, and how it’s shaping the Jewish state and the Jewish society, Israeli society, as we speak. So thank you so much for tuning in. And as usual, if you have questions you want us to ask or guests that you want us to feature, shoot us an email at info@1840.org.

And stay tuned for next week, Monday, for our last episode before we go on a short break for the Chagim. And I think I forgot to say it last week, but thank you to our friends Gilad Brounstein for editing this podcast and Josh Weinberg for editing and recording the video version of this podcast. So until next time, keep questioning and keep thinking.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Chava Green: ‘From God’s perspective, men and women are exactly the same’

Dr. Chava Green joins us to discuss the role of women in the Messianic Era and seeing God in the everyday.

podcast

Chava Green: What Is Chabad’s Feminist Vision?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Chava Green—an emerging scholar who wrote her doctoral dissertation on “the Hasidic face of feminism”—about how the Lubavitcher Rebbe infused American sensibilities with mystical sensitivities, paying particular attention to the role of women.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

Channah Cohen: The Crisis of Experience

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Channah Cohen, a researcher of the OU’s study on the “Shidduch Crisis.”

podcast

David Bashevkin: My Dating Story – On Religious & Romantic Commitment

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, Dovid Bashevkin dives deeply into the world of dating.

podcast

Yabloner Rebbe: The Rebbe of Change

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Pini Dunner and Rav Moshe Weinberger about the Yabloner Rebbe and his astounding story of teshuva.

podcast

Eitan Hersh: Can the Jewish Left Talk With the Jewish Right?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Eitan Hersh, a professor of political science at Tufts University, about teaching students of radically different political and religious views how to speak to one another.

podcast

Liel Leibovitz and Lisa Ann Sandell: When A Spouse Finds Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Liel Leibovitz and Lisa Ann Sandell about what happens when one partner wants to increase their religious practice.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Pawel Maciejko: Sabbateanism and the Roots of Secular Judaism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to historian and professor Pawel Maciejko about the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, Sabbateanism, and the roots of Jewish secularism.

podcast

Eitan Webb and Ari Israel: What’s Next for Jewish Students in Secular College?

We speak with Rabbis Eitan Webb and Ari Israel about Jewish life on college campuses today.

podcast

Child & Parental Alienation: Keeping Families Together

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we discuss parental alienation.

podcast

The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

podcast

Ken Brodkin: A Shul Becomes Orthodox

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Ken Brodkin, rabbi of New Jersey’s Congregation B’nai Israel, about how he helped turn it into “the Orthodox synagogue for all Jews.”

podcast

Dovid Bashevkin: A Reform Rabbi Interviews an Orthodox Rabbi [Denominations 2/2]

David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko about denominations and Jewish Peoplehood.

podcast

Rabbi David Aaron: How Should We Talk About God?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rabbi David Aaron, author, thinker, and educator, to discuss what God is and isn’t.

podcast

David Bashevkin: My Mental Health Journey

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin opens up about his mental health journey.

podcast

Leah Forster: Of Comedy and Community

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David sits down with Leah Forster, a world-famous ex-Hasidic comedian, to talk about how her journey has affected her comedy.

podcast

How Different Jewish Communities Date

On this episode of 18Forty, we explore the world of Jewish dating.

podcast

Mark Wildes: Is Modern Orthodox Outreach the Way Forward?

We speak with Mark Wildes, founder and director of Manhattan Jewish Experience, about Modern Orthodox outreach.

Recommended Articles

Essays

The Four Pillars That Actually Shape Jewish High School

These four forces are quietly determining what our schools prioritize—and what they neglect.

Essays

We Are Not a ‘Crisis’: Changing the Singlehood Narrative

After years of unsolicited advice, I now share some in return.

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

Why So Many Laws? Mishpatim and the Making of a Moral Society

What Mishpatim teaches about human nature, moral fragility, and the structures a just society requires.

Essays

5 Ways the Torah Trains Us to Love Our Enemies

In Parshat Mishpatim, the Torah embeds one of its most radical emotional demands inside its civil code: Help your enemy.

Essays

Why Is Meir Kahane Making a Comeback Among Orthodox Jews?

Israeli minister Itamar Ben-Gvir wears the mantle of Kahane in Israel. Many Orthodox Jews welcomed him with open arms.

Essays

How Archaeology Rewrote the History of Tefillin

From verses in Parshat Bo to desert caves, tefillin emerge as one of Judaism’s earliest embodied practices.

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

A Letter to Children Estranged From Their Parents

Children cannot truly avoid the consequences of estrangement. Their parents’ shadow will always follow.

Essays

Towards the Derech: How Does a Reform Jew Return?

The “way” of myself and other formerly Reform Jews is unclear, but our desire for spiritual growth is sincere.

Essays

How Rav Kook and the Lubavitcher Rebbe Saw the Jewish People

What if the deepest encounter with God is found not in texts, but in a people? Rav Kook and the Lubavitcher Rebbe…

Essays

Is Judaism Fundamentally Zionist?

God promised the Land of Israel to the Jewish People, so why are some rabbis anti-Zionists?

Essays

‘Don’t Wait as Long as I Did’: Seven Stories of Aliyah

A 94-year-old Holocaust survivor, a lone soldier, and more. Here are seven olim sharing their stories of aliyah.

Essays

The Bibliophile Who Reshaped American Jewry

David Eliezrie’s latest examines the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe’s radical faith that Torah could transform America.

Essays

The Siddur Has a Lot of Prayers. Where Did They Come From?

Between early prayer books, kabbalistic additions, and the printing press, the siddur we have today is filled with prayers from across history.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits’ Complicated Portrait of Faith

Meet a traditional rabbi in an untraditional time, willing to deal with faith in all its beauty—and hardships.

Essays

What Commitment Means to Me

I think the topic of commitment is about our very humanity—how we deal with doubt, make decisions, and find and build healthy…

Essays

‘All I Saw Was Cult’: When Children Find Faith

In reprinted essays from “BeyondBT,” a father and daughter reflect about what happens when a child finds faith.

Essays

5 Perspectives on Sinai in an Age of Empiricism

Parshat Yitro anchors Judaism in revelation. But what does Sinai mean in a world where proof is the highest authority?

Essays

R. Abraham Joshua Heschel on Living With Wonder

How can we find wonder in a world that often seems to be post-wonder? Enter Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel.

Essays

Judith Herman Is Giving Voice to Survivors

Dr. Judith Herman has spent her career helping those who are going through trauma, and has provided far-reaching insight into the field.

Essays

The Reform Movement Challenged the Oral Torah. How Did Orthodox Rabbis Respond?

Reform leaders argued that because of the rabbis’ strained and illogical interpretations in the Talmud, halachic Judaism had lost sight of God.…

Essays

Did All Jews Pray the Same in Ancient Times?

Jews from the Land of Israel prayed differently than we do today—with marked difference. What happened to their traditions?

Recommended Videos

videos

Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin: How Torah Gives Us Faith and Hope

In this special Simchas Torah episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin—parents of murdered hostage Hersh…

videos

A Reform Rabbi Interviews an Orthodox Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko (Part 2)

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue,…

videos

Is Modern Orthodox kiruv the way forward for American Jews? | Dovid Bashevkin & Mark Wildes

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Mark Wildes, founder and director of Manhattan Jewish Experience, about Modern Orthodox…

videos

What’s Next for Jewish Students in Secular College?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rabbis Eitan Webb and Ari Israel, head of a campus Chabad and…

videos

The Hasidic Rebbe Who Left it All — And Then Returned

Why did this Hasidic Rebbe move from Poland to Israel, only to change his name, leave religion, and disappear to Los Angeles?

videos

Talmud

There is circularity that underlies nearly all of rabbinic law. Open up the first page of Talmud and it already assumes that…

videos

Joey Rosenfeld: What Does Jewish Mysticism Say About This Moment?

We speak with Joey Rosenfeld about how our generation can understand suffering.

videos

Why Naftuli Moster Left Haredi Education Activism

We speak with Naftuli Moster about how and why he changed his understanding of the values imparted by Judaism.

videos

Zevi Slavin: ‘To be a mystic is to be human at its most raw’

As a Chabad Hasid, Rabbi Zevi Slavin’s formative years were spent immersed in the rich traditions of Chassidut and Kabbala.

videos

What are Israel’s Greatest Success and Mistake in the Gaza War?

What has been Israel’s greatest success and greatest mistake?

videos

Jewish Peoplehood

What is Jewish peoplehood? In a world that is increasingly international in its scope, our appreciation for the national or the tribal…

videos

Moshe Benovitz: Why Religious Change Doesn’t Always Last

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, recorded live at Stern College, we speak with Rabbi Moshe Benovitz, director of NCSY Kollel,…

videos

An Orthodox Rabbi Interviews a Reform Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue, about denominations…

videos

Mysticism

In a disenchanted world, we can turn to mysticism to find enchantment, to remember that there is something more under the surface…

videos

What Do Love and Romance Mean in a Modern World?

Love is one of the great vulnerabilities of our time. Can we handle it?

videos

Sarah Yehudit Schneider: ‘Jewish mysticism is not so different from any mysticism’

Rabbanit Sarah Yehudit Schneider believes meditation is the entryway to understanding mysticism.

videos

Suri Weingot: ‘The fellow Jew is as close to God as you’ll get’

What does it mean to experience God as lived reality?

videos

A Vulnerable Conversation About Shame, Selfhood, & Authenticity with Shais Taub & David Bashevkin

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Shais Taub, the rabbi behind the organization SoulWords, about shame, selfhood, and…