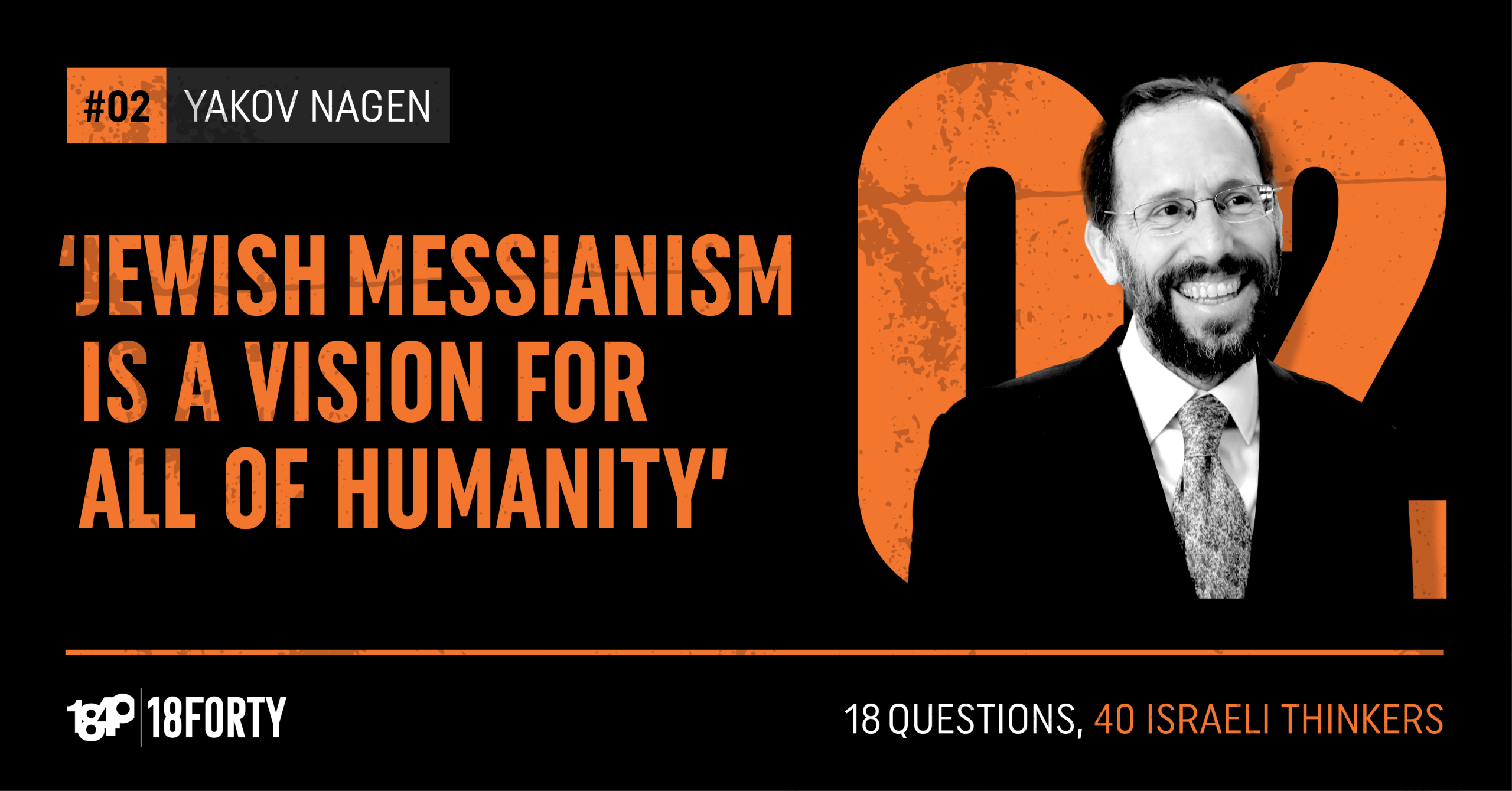

Yakov Nagen: ‘Jewish Messianism is a vision for all of humanity’

Interfaith activist Rabbi Yakov Nagen answers 18 questions on Israel, including Jewish-Musim relations, Messianism, peace, and so much more.

Summary

To Rabbi Yakov Nagen, the Jewish-Muslim fraternity will be the major breakthrough of the 21st century.

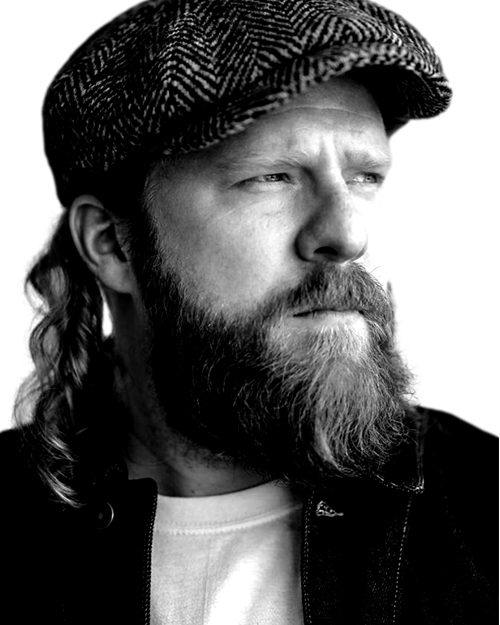

This Religious Zionist rabbi is at the forefront of interfaith dialogue and peace work in Israel between Judaism, Islam, and Eastern Religions. The director of Ohr Torah Stone’s Blickle Institute for Interfaith Dialogue and its Beit Midrash for Judaism and Humanity, he is a passionate voice for universalist Jewish Messianism, which he says is a “vision for all of humanity.”

Rav Nagen teaches Talmud, Kabbalah, and Jewish philosophy as a senior educator at Yeshiva Otniel. He is an extensive writer with four books and hundreds of articles. His latest book on peace and universalism in Jewish Messianic thought, U-Shmo Echad (God Shall Be One), will be released in English this summer.

Now, he sits down with us to answer 18 questions on Israel, including Israeli democracy, non-Jewish citizens in a Jewish state, whether Messianism is helpful or harmful, and so much more.

This interview was held on June 20.

Here are our 18 questions:

- As an Israeli, and as a Jew, how are you feeling at this moment in Israeli history?

- What has been Israel’s greatest success and greatest mistake in its war against Hamas?

- How have your religious views changed since Oct. 7?

- What do you look for in deciding which Knesset party to vote for?

- Which is more important for Israel: Judaism or democracy?

- Should Israel treat its Jewish and non-Jewish citizens the same?

- Now that Israel already exists, what’s the purpose of Zionism?

- Is opposing Zionism inherently antisemitic?

- Should Israel be a religious state?

- If you were making the case for Israel, where would you begin?

- Can questioning the actions of Israel’s government and army — even in the context of this war — be a valid form of love and patriotism?

- What do you think is the most legitimate criticism leveled against Israel today?

- Do you think the State of Israel is part of the final redemption?

- Is Messianism helpful or harmful to Israel?

- Do you think peace between Israelis and Palestinians will happen within your lifetime?

- Are political and religious divides a major issue in Israeli society today?

- Where do you identify on Israel’s political and religious spectrum, and do you have friends on the “other side”?

- Do you have more hope or fear for Israel and the Jewish People?

Transcripts are lightly edited. Please excuse any imperfections.

Yakov Nagen:

There is messianism, which is exclusivity and annihilation of the others. And striving for that type of Messianism is a path of evil and of death, but the Jewish messianism is a vision for all of humanity.

Hi, I’m Yakov Nagen. I’m an Israeli rabbi devoted to interreligious fraternity. This is 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers from 18Forty.

Sruli Fruchter:

From 18Forty, this is 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers, and I’m your host, Sruli Fruchter. 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers is a new podcast that interviews Israel’s leading voices to explore those critical questions people are having today on Zionism, the Israel-Hamas War, democracy, morality, Judaism, peace, Israel’s future, and so much more. Every week, we introduce you to fresh perspectives and challenging ideas about Israel from across the political spectrum that you won’t find anywhere else. So if you’re the kind of person who wants to learn, understand, and dive deeper into Israel, then join us on our journey as we pose 18 pressing questions to the 40 Israeli journalists, scholars, and religious thinkers you need to hear from today.

If religion is part of the problem, then it must be part of the solution. That’s a quote famously attributed to Rabbi Menachem Froman, a fascinating Religious Zionist, Dati Leumi rabbi who passed away a little over a decade ago who dedicated his life and was so heavily involved in peace work in Israel from that religious angle, transcending political divides, transcending religious divides, specifically trying to bridge the gaps between Jews and Muslims, Israelis and Palestinians. If you want an excellent introduction into his work into all the unique parts of it, the controversial parts of it, go on our 18Forty website. Yehuda Fogel, our in-house editor has a phenomenal primer on Rav Froman.

It’s missing a picture because we had some copyright issues, so don’t be deterred from that, but I highly recommend it. The reason why I’m bringing Rav Froman up for this interview specifically is because our guest today is Rav Yakov Nagen, a student and friend of Rav Froman, who to many is carrying on the torch of his legacy and the work that he does. Rav Nagen is a Religious Zionist rabbi who is a leader in Israel in interfaith work between Israelis, Arabs, Palestinians, Christians, Jews, Muslims, everyone who’s here, but specifically Judaism, Islam, and Eastern religions is where he primarily focuses.

As he’ll talk about in the interview, he’s particularly interested in Jewish-Muslim relations. Rav Nagen is director of the Ohr Torah Stone Interfaith Center, which encompasses a lot, including the Beit Midrash for Judaism and Humanity, the Blickle Institute for Interfaith Dialogue, which I totally mispronounced when I was interviewing him, which when we were speaking afterward, and he corrected me. So, it’s not Blickle Center. It’s the Blickle Center if anyone ever has to reference it again, so just keep that in mind. Rav Nagen wrote a phenomenal book called Ushmo Ehad. It’s in Hebrew, and it has several different authors. It’s not actually just him. I think he was an editor of it, or it was from one of those centers from Ohr Torah Stone, which has a lot of essays exploring the philosophical and biblical dimensions of what type of vision we’re all working towards of a universalist, not just a Jewish future, but a universalist future of how Judaism is meant to bring about a messianic universalism that applies to all nations and all people.

So to preface this interview, if anyone is trying to put Rav Nagen in a box, they’re going to fail to understand him. He is a messianic religious Zionist who doesn’t quite fit into right or left categories. As he elaborates, his vision for Zionism, for Judaism is very loving, very universalist in its implications. At the same time, he is still a strong defender of Israel as a Jewish state. There’s a lot to unpack there of what that means practically, what that looks like, and what that means in the context of today. But needless to say, Rav Nagen is a figure of hope for today. One of the things that he said that really struck me in the course of our interview, and he was really trying to drill this point home, is that in his view, and this is where he’s very deeply involved with, the 21st century is a major breakthrough of Jewish-Muslim fraternity with the Abraham Accords with so many other things that are going on in the world.

He still is not losing hope on the potential for that and the potential for us to bring in this messianic future that is peaceful, that’s loving. So if you’re looking for hope of someone who’s deeply involved in this work, in interfaith work in Israel, at a time when it’s so desperately needed to reassure us about our future, Rav Nagen is your person. I have been a huge fan of his for so long. His writings are incredible. He has, I believe, four books, hundreds of articles on spirituality, on peace, on so much more. You can really just Google him, and you’ll find a treasure trove. But enough of my rambling, I’m very happy and very excited to introduce you to Rav Nagen. So, here is 18 Questions with Rabbi Yakov Nagen.

As an Israeli and as a Jew, how are you feeling at this moment in Israeli history?

Yakov Nagen:

I think for Israelis and Jews throughout the world, October 7th and its aftermath is transformational, true on with our personal lives and our feelings is part of the Jewish people and part of humanity. Certainly as a Israeli Jew, it’s very personal. The pain and trauma are very close. It’s students, friends, neighbors, or among the dead and injured, and everything we think about … we have to rethink. In many ways, I felt that in the great story of the Jewish People, we have gone to the… If in the past I would talk about the Jewish People on survival mode, we have now the luxury to go into vision mode, building the great vision of the future of the Jewish people.

October 7th returned us and certainly me to realize how fragile the world we live in. Yes, we won’t give up on dreaming about the vision of the future, but the survival mode, which was so much a part of the story of the Jewish people throughout ages, it’s back again.

Sruli Fruchter:

What has been Israel’s greatest success and greatest mistake in its current war against Hamas?

Yakov Nagen:

Success and failure, I would probably relate to the different stratas of society. If you want to see part of the positive, I think it’s going to the people. We went so fragmented in the judicial debate before that, feeling that society’s falling apart in a dualism of us against the them, and the us and the them being other parts of Israeli and Jewish society. The greatest success is what the times and places we went beyond that. In fact, even on a personal note, on every day in prayer, the blessing of Modim, of thanking God is part of the daily prayer, and the words are fixed, but I always try to add some personal words of my own, of something from today to thank God for.

I was deeply challenged in the aftermath of October 7th, because the trauma and the pain was so overwhelming. The little things that I would give thanks for each day seemed trivial in comparison. But at some point, I felt, yes, with all the trauma to express gratitude to God that I am a part of my people, that I am part of the Jewish people, and that also brought me the insight of how much we are family if just like family could bicker with one another as only family could. I think this characterized Israeli society before October 7th. After October 7th, like family, we’ve come together whether Jews in Israel, Jews in the world.

I think sometimes, some of the media portrayals of different demonstrations or the like have not correctly characterized the deep solidarity and unity and empathy for one another, which still today still characterizes the people of Israel and the Jewish people through the world. The feeling I would see as relating to the leadership, I feel we deserve a better leadership, and that bickering and which characterized society as a whole, somehow the reality of the Jewish people in Israel abroad that solidarity, that going beyond personal interest, self-sacrifice. Unfortunately I don’t feel this characterizes our leadership.

I think they once said about the British army that it’s a army of lions led by mules. I think some paraphrase that could be applied to Israeli society today.

Sruli Fruchter:

How have your religious views changed since October 7th?

Yakov Nagen:

I’ve been reading a lot of the Bible since the October 7th, in particular, the later Prophets. Part of it, I feel October 7th is a global event, meaning realizing it’s not just about us. It’s not about this tiny country called Israel, so much smaller than so many other larger countries that almost no one can place on the map, and the struggle with the people in Gaza, realizing there’s a global event taking place. It’s not just about us, and the forces on all sides are much greater than the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. For me, that brings me back to the visions of the Prophets that for many reasons have been guiding me for years as I’ll elaborate later, that the prophets talk about a future that deals with global realities.

I think about close to 3,000 years ago or 2,500 years ago, whatever your timing or … scholarship is, how on earth are they talking about the global society from the far east to the far west, from the corners of the earth? I mean, you grew up in the little village. You grew up in… You take your camel a little bit to the left, a little bit to the right, but the path is the Prophets is talking envisioning a future. Part of it is the return of the Jewish people to the land of Israel beyond hope, beyond belief has happened. Part of it is a future of global events, some positive but some negative of conflict and connection. For me, in the deepening of the simple religious faith that there’s some great story that we’re a part of that’s unfolding, I feel that emphasized in the current realities.

I go back to these ancient books, and even if I can understand why things are so traumatic and painful, it does give a feeling that this is a great story which is unfolding that was foreseen. So, that’s one aspect, maybe of personal religious, but certainly, something which I’m sure we’ll talk about later. This has impact a lot on my interfaith work. If Dickens at the beginning of A Tale of Two Cities says: It was the best of times. It was the worst of times. I think the interfaith, certainly Jewish-Muslim interfaith, we could say it is certainly the worst of times people understand, but the best of times or perhaps meaning it’s more important than ever. That’s the position that I try to defend and have been working on.

Sruli Fruchter:

What do you look for in deciding which Knesset party to vote for?

Yakov Nagen:

Wow. So, certainly, I’d rather not tell a particular party, but really hoping of the vision of what I would like the Knesset to be about, and I hope a party would emerge. There’s a tragic book by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks called Not in God’s Name that talks about how so much evil could be done in the name of lofty ideals. Part of it talks about a pathological dualism. The pathological dualism is the world’s divided between the us and the them. This division is what brings of the good and the evil, the light and the darkness, those who are right and those who are wrong, and that dualism is at the source of collapse of society. I was born in America. I still love America, and bless America, and it’s heartbreaking to see the conflicts between the Democrats and the Republicans.

I’m thinking, “Oh my God, what are they at their throats?” These issues seems to be so much less cosmically significant than the reality of connection and being together. So, I feel in essence, it’s about connection. It’s about relationships. I would want a party that would not be a party that would be looking for government, that would be … 100% on the right, 100% on the left, but something that would be about connections. Connection doesn’t always mean, “Let’s take the middle ground,” because sometimes people in the middle could be as radical and rejecting of other people. We are the people who have seen the light to be a middle of the road, but anybody who veers a little bit to the left, a little bit to the right of us, they’re totally illegitimate and mistaken and a danger to society and democracy, something that would be able to give a place for different groups.

So, I will confess that the previous government, I was deeply moved that we had a prime minister who was a religious Jew, that we had a religious Muslim party, parties from the left, parties from the right. So, it would be less about particular opinions, but the ability to make connections. Maybe to give another point about this, that how important relationships are, if you look at the government, part of the dysfunctional aspect of the Knesset is personal rivalries between people that have very similar political views, have let them not being able to sit together, which teaches us that relationships and connections, and being able to sit together, talk together is more important to exactly where you stand on some spectrum of more to the left, more to the right.

Sruli Fruchter:

Which is more important for Israel, Judaism or democracy?

Yakov Nagen:

That’s another dualism that I deeply reject. I feel some of these words have been hijacked to really misrepresent them, the concept that it’s either or. Not only do I think it’s not either or, I don’t think it’s sacrifices and compromises of democracy and Judaism. I feel that the core values of what are seen to be democracy are authentic, deep core Jewish values. We could go back to the Declaration of Independence. We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal. Sorry about that gender of terminology. All humanity are created equal, which I think should be written today, and the right to liberty, et cetera.

These are basic divine Jewish values. So, creating a dualism, either or, this itself sets it up for failure. True that sometimes you could have two authentic values, and how to integrate them in an ideal way will create challenges in terms of how to realize our values and complex realities. But in the essence, it’s two sacred values, divine, authentic and Jewish values, and always how to balance and weave together.

Sruli Fruchter:

Should Israel treat its Jewish and non-Jewish citizens the same?

Yakov Nagen:

In one of my institutions, the Beit Midrash for Judaism and Humanity, we are now completing a book about how a Jewish state as a Jewish states relate to non-Jewish minorities. It’s a core value in the Bible minority issues. So often, the Bible goes back to remembering the traumatic times that we were a persecuted minority in Egypt, and from that to have empathy with other minorities, to love them, to ensure their rights, and learn. This is not something that could be taken for granted. Sometimes, an abused child could become an abusing parent. To say learn from our painful experiences, and learn from them, take the right messages and not the wrong messages. This is a powerful message of the Torah.

I think we were in Egypt for several hundred years. We were in exile from the Land of Israel for 2,000 years. Here too, our painful journey should open us to understanding and empathy and realizing that part of a Jewish state is the fulfillment of a vision in the Bible of how a Jewish state should relate to its minorities. In the book, I try to take an additional step, because in the biblical categories of Hebrew, ger toshav, the stranger resident, I feel, doesn’t capture some of the potential for current realities, because in the current realities, the minorities of Israel, we have a great shared both religious and ethnic heritage. The religions of Israel, the four religions because it’s Judaism, Islam, Christianity, and the Druze religion.

Ethnically, we are Jews and Arabs. We acknowledge each other’s ethnic identity as returning to our patriarch, Abraham. Our religions share so much of a common story. So, I feel if in biblical times, minorities’ rights were about tolerance, I feel there’s a potential for partnership in the current realities in the State of Israel, because we share so much of a common story and values. That being said, and there’s still a place, and I still will stand by Israel being a Jewish state, every state, every nation has an identity, and to erase, to erase identity, to have no identity at all in order makes the world poorer and grayer.

Israel is the one Jewish state in the world, and there are Muslim states in the world. There is a French state in the world, every country. It could be a religious identity. It could be a linguistic identity. It could be a cultural identity. John Lennon’s view of imagine no nation, no religions I feel will leave to an impoverished world, and the enforcing of no nations, no religions would probably require a totalitarian oppressive society as we see from the communist regimes. Israel is a Jewish state of the Jewish people. So, I am for partnership, minorities, dignity and rights, which includes and is not undercut by a place of dignity and respect to our minorities.

Sruli Fruchter:

Now that Israel already exists, what’s the purpose of Zionism?

Yakov Nagen:

I have a friend that once wrote a book called The End of the Adventure is the Beginning of the Story. Meaning there are all these fairy tales that there are these dramatic events, and then ends, “And they lived happily ever after.” My friend pointed out, the end of the adventure is the beginning of the story. What really matters is what is the life that the people built together, the prince and the princess. So, the prince slayed the dragon. Okay, what really matters is what life do they build together? The same way with Zionism, I feel Zionism is saying that the Jewish people who as Rabbi Jonathan Sacks wants to find us, we are not a People that have a story. We are a story that have a People, that we take our destiny into our hands.

As Religious Zionist, I believe this is in partnership with God. We take our destiny into our hands to build the story and the future of the Jewish people. Our ancestors for 2,000 years went through hell to preserve the Jewish identity with so many easy exits out to save them for persecution, but they kept their identities that one day their descendants will be able to live Jewish life in its fullest to return as in all our prayers to the land of Israel, to Jerusalem. We owe it to them that the reality of life in Israel, the state of Israel in our capital of Jerusalem, to create a reality worthy of their great sacrifice. There’s a movie Searching for Private Ryan in which there’s a scene that somebody gives his life for someone else, and his last words are, “Do something with it.”

I feel we have 2,000 years of our ancestors who with incredible self-sacrifice to tell us, “Do something with it.” For me, Zionism isn’t just the technicality of the Declaration of Independence for the state of Israel. It’s not only overcoming the survival. It is the realization of the great vision of the Jewish people in their homeland after this incredible journey. Here, we are not at the end of the story. We are at the beginning. In this context, I feel that if my work in interfaith is part in parcel of my Zionism, so I feel that the same way, part of Zionism is saying, “We must be active partners with God to realize this vision of this return to the land of Israel.” Zionism also to fulfill the potential of this vision, which is for me, it’s also healing our relationship with humanity.

For Zionism, it might include our brothers and sisters throughout the world, because in our global society, as we’re seeing now the painful aspect of it, the reality of a Jewish state, the state of Israel impacts and creates a partnership with all of our Jewish brothers and sisters throughout the world.

Sruli Fruchter:

Is opposing Zionism inherently antisemitic?

Yakov Nagen:

Yes. The short answer is yes, because Zionism is an acknowledgement that part of the Jewish, Judaism is not just an abstract religion. Judaism is a people. As I said earlier, it’s a story with the people, and an essential part of that story from the Bible, from the prayers we say every day, from the ceremonies that weddings and all of our life cycle, it’s an essential part of that peoplehood. It’s connected to a place. It’s connected to a home, a homeland. So, denying Zionism is denying Jewish peoplehood, is denying the Jewish story. Yes, that is antisemitism. Maybe the word antisemitism, I don’t think it’s a word that truly captures the pathological hatred and denial of the Jewish people, and our story that’s been taking place for thousands of years, and tragically beyond our worst fears has been reborn in demonic dimensions.

Sruli Fruchter:

Should Israel be a religious state?

Yakov Nagen:

Israel is a Jewish state. I feel that if religious … Depend on what does it mean a religious state? If religious state means that totalitarian control of what people do or don’t do, no. But if it’s a state that is a realization of the core Jewish story, values and promotes, promotes the key story and values of Judaism, yes, I think that’s religious. Yes.

Sruli Fruchter:

If you were making the case for Israel, where would you begin?

Yakov Nagen:

Our story, our identity. In wake of the war, I was at a conference in Jakarta Indonesia, and one of the questions I was asked about, “What’s my opinion about Israeli colonialism?” I feel there’s one of the narratives which has been underlying a lot of the antisemitism, which is a denial of our legitimate story and legitimacy, the narrative of the Jewish people as the ultra white Europeans who have been taking away, colonializing the place of the indigenous authentic people of color at the Middle East. This is underlying what I see as the major force of antisemitism much more than Islam, which my focus is, but the neo-Marxist left.

The response to that is not to give up our deep religious ethnic identity, the Jewish people and our story to the land of Israel, which is now the state of Israel. It’s from our authenticity and authentic connection. This must be at the forefront.

Sruli Fruchter:

Can questioning the actions of Israel’s government and army, even in the context of this war, be considered a valid form of love and patriotism?

Yakov Nagen:

This is a broad question, and I once said about the issue of giving rebuke. When do you know if rebuke is coming from the heart to help the other person, or is it coming from some ego or whatnot? So I say, “If you feel like saying it, then perhaps don’t do it, because it’s coming from ego.” If you feel the last thing you want to do is to open up your heart about some issues, but you do it anyway because you feel such a necessity, then maybe open the possibility. But even there, it’s critical to do in a way which will bring greater good to the world, light to the world, and not darkness to the world.

Even in the Talmudic laws of rebuke, part of the laws is if it’s rebuke, which by the way is juxtaposed in the Bible to v’ahavta l’reiacha kamocha, loving the others yourself is hochiach tochiach et amitecha, to rebuke your people. The Talmud says if it will be accepted, if it’ll help to make a positive change, yes, but if it will not, no. Unfortunately, a lot of the critiques of Israel, the format that they’ve been done, who it’s been presented to, not only have they led to the pathology of vicious demonizing of Israel and antisemitism playing to the hands of our most vicious enemies, but more than that, it has made Israelis, harden them and maybe close their ears when there’s so much outrageous, blood libels, Orwellian inversions of all truth and reality in criticizing the Jewish people, in criticizing the State of Israel.

This undercuts the ability to truly give any authentic critiques. The results have often been the opposite. Just like the BDS movement, the idea of boycotting Israel, if anything, creating … If the heart of the problem in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is the deep disconnection that breeds fear and hatred, so let’s boycott and not talk to each other, and sanctify disconnection. If those people indeed had some concern for Palestinians, it is totally self-defeating.

Sruli Fruchter:

What do you think is the most legitimate criticism leveled against Israel today?

Yakov Nagen:

So first of all, I would try to reframe that question. Criticism leveled against Israel in a country in trauma with enemies trying to destroy us, criticism leveled against is by the very energies and terminology is the other side attacking us. I would give an answer to a reframed question that would be, “What mistakes, perhaps some aspects of Israel and Israeli society are making in the current conflict?” I feel that there’s recognizing the global aspect and the implications of the global aspect of this conflict is important to overcome it. This is true in a number of areas. For example, something which I hope we’ll speak about more later, a lot of the focus of my work is Jewish-Muslim relations or the hope to create a Jewish-Muslim religious fraternity.

Again, and for reason which are deeply understandable, the great trauma of the Hamas talking in the name of Islam, quoting Islamic sources in their barbaric atrocities has understandably led to a perception that there’s a conflict between Islam and Judaism, which in my belief, it’s falling into the hands of the enemy. Exactly, this is what they want to create a world that the Jewish people are in conflict with Islam, or some will see the Jews are in conflict with the world, that the trauma has left people feeling everybody hates us. We could only depend on ourselves. I feel that opening up to what I see the reality is yes, we’ll not deny there’s a lot of evil in the world.

There’s a lot of antisemitism in the world, but there’s also a lot of good in the world. I feel the criticism I have is not the full for that pathological dualism of it’s everybody against us, but to get the complexities of our multi-faceted world, not to deny the evil, but to realize that we have allies, we have friends. There’s good and light in the world, including certainly within Islam and also certainly within Arabs in Israel. To acknowledge that and help empower that, this will give, first of all, due respect to those forces that should not be lumped together with our enemies, and I think create a better reality.

One example that I would like to bring, and perhaps something which I find optimistic in these dark times, in Israel, there are two million Israeli Arabs. They are one of the blood libels against Israel is about apartheid and the like. I think Israeli Arabs enjoy more civil rights than any citizens in any other country in the Middle East, because the freedom in Israel, I think, is unparalleled by the other countries in the Middle East, but there are fears at the beginning and fearmongers at the beginning after October 7th, that predicted, which was a fear that would the two million Israeli Arabs on some level join in to this war waged against Israel? Would there be a repeat about the riots several years ago in the mixed cities in Israel?

That was not the case. Of course, there are always exceptions, but by and large, the Israeli Arabs have stood together in a very complex situation with the Jewish citizens. In particular, I would like to mention Mansour Abbas, the head of the Ra’am party. Fascinating fact, this is the four Arab parties in Israel. This is the religious Islamic party. He has been outspoken against the atrocities, and tragically certainly in the South, the 300,000 Israeli Bedouins of the South have been partners also in the suffering among the captives, among the murdered, among soldiers fallen, which has been the case also in the north, and certainly among Israel’s small Druze Arab population.

I went to give consolations at a Muslim soldier from Rahat who was killed in combat fighting the Hamas, leaving his young wife and a beautiful little daughter. So, this is my realize, getting not the same pathological dualism that has led to demonizing the Jewish people in Israel. Let us not be part of that, and realize, “No, Islam is not in a war against us. The Arabs are not in a war against us. The world is not against us,” but there’s real evil, and we must find, build partnerships to overcome it.

Sruli Fruchter:

Do you think the state of Israel is part of the final redemption?

Yakov Nagen:

I believe that not only for the Jewish people, but in the story of humanity as a whole, the return of the Jewish people to the land of Israel, the return of the Jewish people to Jerusalem is one of the most amazing, greatest chapter of this book.

Something that goes beyond ability to explain some sort of a historical coincidence at most. If coincidence is using the definition of Albert Einstein, coincidence the way of God to remain anonymous. This is a story for humanity because most of humanity, their story is based on what happened here, because it’s not just the Jewish people. It’s Islam. It’s Christianity and all of society.

There’s no in the world that hasn’t been influenced by these Abrahamic religions and this great vision of the Jewish People returning to where it all began, and to realize that there’s something enormous taking place for the world. I feel one has to be blind not to see that. Therefore, I often say when people talk about the relationship of the world to Israel, I say it’s not hate. It’s not love. It’s obsession. There is an obsession about what happens in our tiny country. The world is so big. Our nation is so small, but this global obsession has to be understood. Let me mention, I once visited an Arab school in Kfar Rameh in the north of Israel. I asked the children, Arab elementary school children.

I asked them, “Why do you think that even when little things happen in our country, the whole world’s talking about them?” So, these young, sweet, young Arab children said, “Because they know it all started here.” There’s a feeling something very big started here, and some intuitive feeling that here and what happens here is still important for this story of humanity. That’s why I think what happens here, issues about, is Israel living with its neighbors in peace, its minorities, the status of religion, and the place of the Divine within life. These have repercussions beyond what happens in our tiny country, but impacting the world as a whole.

Sruli Fruchter:

Is messianism helpful or harmful to Israel?

Yakov Nagen:

As many questions, the question is what is meant by messianism? Will messianism be a future for me and not for anybody else or anybody who’s a little bit different than me? This could lead to the greatest of evils. Part of the pathology of the Hamas is they believe we are part of a messianic story. Perhaps I’ll give you one of the Islamic backgrounds for the Hamas attack. The 17th surah of the Quran is a surah that begins talking about the night journey of Muhammad to Al-Aqsa, the faraway mosque, which is in the blessed land. In the Quran, the blessed land is always used exclusively for the Land of Israel.

It then tells the story about the first and second temple, Beit HaMikdash. That’s why one of the names of this 17th surah is Bani Isra’il, Children of Israel. Close to the end of the surah, it tells about the Jews left Egypt, and came to the blessed land. Then in verse 104, for those have a Quran, it talks about, “And in the promise of the hereafter, the Jews will return to the land.” On the surface, certainly, this is seeming to be some sort of a Zionist prediction, similar to the prophetic works of in the Tanakh. The pathology of the Hamas says, “Yes, clearly, the Jews are evil. The Jewish people have been rejected by God. Judaism is obsolete.” So if the promise of the hereafter is the Jews will be brought back to here, they said, because then there’ll all be in one place, and therefore we could give them their last justice, judgment, which will be annihilation.

The Hamas would have a yearly conference called, you could Google it, the promise of the hereafter. So, there is Messianism, which is exclusivity and annihilation of the others, those others. Striving for that type of messianism is a path of evil and of death, but the Jewish messianism is a vision for all of humanity. There’s one verse which very much touches my heart and work. I’ll explain on a personal level why. In the verse in the Book of Zephaniah, it talks about humanity calling together in the name of God, and serving him one shoulder. For me and also in a book which will soon to be translated into English called God Shall Be One, re-envisioning Judaism’s relations with world religions, we present the vision of the future, not of Judaism becoming the global religion, but showing in a book very source-based.

Our vision is connecting up with humanity and their religions to find a way for fraternity, and calling together in the name of God. For me, this is personal, because two years ago, I had a very serious brain hemorrhage. The way that the president of Israel, Isaac Herzog called it, he goes, “Yakov was on his way to the other world, but we called them back by our prayers.”

During that time when I was hovering between life and death, my wife turned to the Jewish world, and so many of my Jewish brothers and sisters responded with their prayers, but she decided to reach out also to the other religious communities. So, using Google Translate for whether Indonesia, Middle East, Muslims, Christians, every father, bishop, imam, qadi, she sent them, “We need your prayers now.”

It was an overwhelming response, and I was blessed to come back. So for me, I felt in a small way, calling together in the name of God has some small fulfillment, but this is the Jewish messianism. Three times a day, Jews pray. The end of our prayer is called the Aleinu, which ends with a vision that in the future, humanity is serving God, and on that day, God shall be one and His name one. So, this is the vision we’re praying for, which is universal, which is for all of humanity with a place for all.

Sruli Fruchter:

Do you think peace between Israelis and Palestinians will happen within your lifetime?

Yakov Nagen:

I think if this is a yes or no question, this could undercut the ability to move ahead, because it seems so far away that people could lose faith. Students of mine sometimes say, “Rabbi Yakov, the fact that you talk to these imams, do you think that’s going to bring peace?” So, I tell them, “You don’t understand. If me a Jew, a rabbi, creates a real, authentic relationship and connection to another person, a Muslim and imam, and there’s true friendship between us, this isn’t only a means to an end. This is peace. This is shalom. This is happening right now between us. It’s here now.” We would like to multiply this by millions.

So perhaps dear students, let go. Make peace. Find the other Palestinian, Arab, Muslim or Christian. Create a relationship. Create a connection, and that will be to create peace in your lifetime. I think perhaps it’s important to explain the difference between the word peace in English to the beautiful word shalom in Hebrew. Jewish peace is about connection. Sometime, peace programs are about us here and them there, big walls, big disconnections. Peace is about connection. If I could share you a mystical teaching from the Zohar, the word shalom begins with the letter shin, which in Hebrew represents aish, fire. It ends with the letter mem, which in Hebrew represents mayim, water.

Shalom is to take elements that are different in some ways in conflict with each other, fire and water, and bringing them together, or as I say, Jerusalem, the word Yerushalayim has in it the word shalom. Many of the prayers and the Psalms of Jerusalem talk about shalom. I think there are three approaches to Jerusalem. One, it’s about the three Cs. Is it control? Is it concede, or is it connection? For some, it’s all about power. Who has the power? For some, say concede. Well, it’s crossing us a headache. Maybe if we give it to the other, we’ll solve the problem, but I believe Jerusalem, it’s about the sea of connection. In fact, again, if we go back to messianism, messianism sees the temple as a house prayer for all people.

The alibi for the Hamas for their murderous attack against Israel was Al-Aqsa in danger. I feel both in Islamic and Jewish sources, this is a blasphemous, sacrilegious attack on that holy place, because certainly from a Jewish view, the Temple Mount is a place of connection. Whereas, like I said before, Isaiah, a house of prayer for all people. So many prophecies talk about the future of humanity coming to Jerusalem, and Islamic sources also in the Hadith, the account of Muhammad going up to heaven from the Temple Mount, and that’s from Al-Aqsa, where in Islamic tradition, receive the pillar of prayer. On the way, he meets Moses, and they have a discussion between them. They refer to each other as brother.

First, Muhammad goes up, is told, “Pray 50 times a day.” Then Moses says, “It’s too much. Negotiate with God,” and they keep going back and forth till Moses helps Muhammad get down to five. But, you see the respect in Islamic tradition for Moses. Islam seek certainly as Jews as the primary Jewish prophet. So, what better place for Jews and Muslims and Christians who sharing our one God to express our brotherhood and our sisterhood to come to brotherhood to pray to God. So, using Yerushalayim, Har HaBayit, Al-Aqsa for evil and violence as Hamas does, this is a great sacrilege, but so in peace, I feel we must embrace every step along the way. By doing that, we’ll have the motivation and faith to take that next step to make it broader and deeper in building the connections and relationships between all who live here.

Maybe one last point here about the power and how I feel that this is what so much of humanity is looking for. One day, in the yeshiva that I teach at, I’m called to the office, and told, “You have to see this.” I’m wondering, “Why are they calling me out of my study hall?” They’re showing me, “Google has this one minute clip called the year-in review of the great picture of the year.” I’m thinking, “Why are they showing me this to me?” When we got to second 40, I realized the year-in search Google picks a picture for all the great questions that people searched for answers during the year.

In searching to make sense, I saw a picture of myself hugging my dear soul brother and friend, Sheikh Ibrahim from the Mount of Olives, hugging each other in an event called the Jerusalem Hug, in which Jews, Muslims, and Christians, Israelis and Palestinians come together to hug the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem to say, “We want Jerusalem to bring us together, and not separate us.”

Sruli Fruchter:

Are political and religious divides a major problem in Israeli society?

Yakov Nagen:

Unfortunately, in the current realities, the answer is yes. This perhaps is one of the greatest challenges for Israeli society to overcome these divisions between left and right, religious and secular. For me, often, I’m asked, “Why is it that I deal so much with issues of interfaith with Judaism and humanity, that there are so many internal problems within Jewish society?” One of my answers is that if we look deep down, so much of the tensions between the left and the right, the religious and the secular, go back to the broad issue of what is the relationship between Judaism and humanity, the perception that the right is exclusivism as opposed to the left, which is universal, which also that religious people have no interest or connection to broader global culture and events.

This is part of what creates that great divide. So, I feel that by the Jewish People in the name of religion, rethinking its relationship to these issues, this could make breakthroughs in places that are stuck to see that a Jew living on what’s referred to as the West Bank could be somebody who deeply cares about the future of his Palestinian neighbors while being deeply connected to his home and his land, to feel that his religiosity allows him to be in connection with the other, and not this himself. With many different secular friends, I have people which they called on the left, how moving it could be for them to rethink what they think about, about the borders, boundaries and conflicts in Israeli society.

Sruli Fruchter:

Where do you identify on Israel’s political and religious spectrum, and do you have friends on the “other side?”

Yakov Nagen:

It’s hard to answer identify because too much part of the problem, you’re this or that. If you’re this, if you’re right wing, this means you’ve already ascribed to a dozen beliefs that are attributed to you, and the same if you’re left wing. So, that certainly politically, I would find it difficult to respond, to put myself into a box. I feel part of the hope of Israeli society is not if you are A or B, say, “Yes, I’m right wing,” but not only despite that, but because of that, I believe in some things that would seem to be the opposite and the same for left. But I will say in terms of, I would say, identify as a Religious Zionist, and in the definition that I give Religious Zionism certainly is a religious Jew who’s committed to the will of God, and living based on the Torah and halacha.

The Zionist part, as I tried to define earlier, Zionism is saying we need to be active partners in the unfolding of the story of the Jewish people, which I would say perhaps differences ourselves from our ultra-Orthodox brothers and sisters that are also, we share with them our Jewish religiosity, but the feeling of the active role we must play in building the state and the army. So in terms of perhaps culture, Religious Zionism, I’m comfortable, but using the word political definition, things are too polarized to give a multiple choice, A, B, C or D to that question.

Sruli Fruchter:

Do you have friends on the other side?

Yakov Nagen:

Yes, I am blessed to have friends. I feel that part of the essence is if we define ourselves and the other based on our religious and political ideologies, then you’ll be cut off from so much of the blessings of being part of a society, of a state. But if you start with the person, and their ideologies and opinions are number two, that allows to create friendships and connection. In general, three sacred words that I like to say together is connection before correction. First, have that connection, or as the SSufi mystic Rumi said, “Beyond ideas of right thinking, beyond ideas of wrong thinking, there is a field. There, we’ll meet.”

There’s no human that lacks a field that we could meet. So, first have that connection. Afterwards, we could talk about correction. We could agree. We could disagree. We could be blessed by our differences.

Sruli Fruchter:

To close us off, do you have more hope or fear for Israel and the Jewish people?

Yakov Nagen:

Hope. If you go back, study the entirety of the Jewish people from beginning to end, we see that we are no stranger to traumatic, difficult periods, and we are no stranger to even conflicts within internal Jewish society. We haven’t invented any new problems that haven’t been haunting us for millennium. But with that, the potentials and the possibilities that we have within the State of Israel, within the return to Jerusalem, give us a potential to overcome the problems that were always there. So, those who have forgotten the past could feel overwhelmed with the problems of the present. But with the broad perspective, we could see the big picture, and not be overwhelmed.

In terms of hope, let me share with you a major project that myself and my institution, the Ohr Torah Interfaith Center, is working on. In the 20th century, there was a tremendous transformation of Jewish-Christian relations in a process referred to as Nostra Aetate. The Catholic Church overcame 2000 years of institutionalized antisemitism negativity about Judaism and the Jewish People beginning a process of dignity, fraternity, and respect to now feeling that language when many Christians speak about Jews as our older brother. I believe that the next step in the 21st century, we need a Jewish-Muslim religious fraternity, not in any way to undercut the strides of Jewish-Christian relations, but to emulate that in a process ahead.

The potential here is great because certainly in the Middle East, Jews and Muslims, when it’s Jews and Arabs, we see ourselves not only sharing a religious patrimony, but also an ethnic patrimony, Jews, descendants of Isaac, and the Arabs of Ishmael. To reframe our story as there were family, as I said earlier about Israeli society, families bicker. Only families could bicker as this Book of Genesis tells us about Joseph and his brothers, Isaac and Ishmael, Jacob and Esau. So too, there’s tensions in the family, but the families must be wise, overcome those conflicts, and create a family devotion and love for one another. This potential is there.

We are working a lot on the theological basis for it to see how there’s a place for different religions, and a great story that could be built, including our identities and religions. I feel a sign of great hope is the Abraham Accords, the Abraham Accords, which is opposed to Oslo and Camp David, other peace accords between Israel and the Arab neighbors, the name given to the recent peace agreements come from our common heritage, Abraham, and symbolizes that Abraham, our religions, our religious beliefs and figures and identities could bring us together, and no longer set us against each other. I remember I studied at Yeshivat Har Etzion, and there were some difficult periods that some of the students were very distraught, but Rav Amital, the Rosh Yeshiva, who survived the Holocaust, fought in the war of independence, he was feeling how …

I would say even almost painful for him to feel the lack of proportionality in realizing the great times that we’re living in with this incredible potential, and this we must open our eyes to. In the Torah, they talk about the generation that left Egypt, and sometimes they’re worried about so many issues that for us, it’s shocking when we think they’re living in this incredibly historic cosmic time, and they’re worrying about all these minor issues. I’ve seen people say, “Well, let’s think about ourselves, because perhaps we are now in the most significant time period for the Jewish people since that beginning.” To broaden our perspective, yes, there are the problems, but there’s a potential for hope that b’ezrat Hashem, please God, we will fulfill.

Sruli Fruchter:

If you listened to our first interview with Benny Morris, then I’m sure you saw very stark differences between Rav Nagen and Benny Morris. That’s very much the idea of what 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers is going to be like. All weeks are going to be different. All perspectives are going to be different. One week, we’ll have a religious thinker, the next week, a journalist, next week, a political thinker. The following week, it’ll be a historian. We want to introduce, as I said in the intro, fresh perspectives, challenging ideas for everyone who’s listening. So if you have questions you want us to be asking, or guests who you want us to be interviewing, please shoot us an email at info@18forty.org. That’s I-N-F-O@18forty, 1-8-F-O-R-T-Y, .org.

Please be sure to follow us, and share this episode with others so that we can reach new listeners. If you’re looking for any other content, all things Jewish ideas, visit us on 18forty.org. That’s 1-8-F-O-R-T-Y.org, where we have podcasts, essays, recommended readings, newsletters, programs, and so much more. Thank you for listening.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Yehuda Geberer: What’s the History of the American Yeshiva World?

We speak with Yehuda Geberer about the history of the yeshiva world.

podcast

Alex Clare: Changing in Public

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Alex Clare – singer and baal teshuva – about changing identity and what if questions.

podcast

Aaron Kotler: Inside the Lakewood Yeshiva

We speak with Rabbi Aaron Kotler about the beginnings of the American yeshiva world.

podcast

The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

podcast

Julia Senkfor & Cameron Berg: Does AI Have an Antisemitism Problem?

How can our generation understanding mysticism, philosophy, and suffering in today’s chaotic world?

podcast

Micah Goodman: ‘I don’t want Gaza to become our Vietnam’

Micah Goodman doesn’t think Palestinian-Israeli peace will happen within his lifetime. But he’s still a hopeful person.

podcast

On Loss: A Spouse

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Josh Grajower – rabbi and educator – about the loss of his wife, as well as the loss that Tisha B’Av represents for the Jewish People.

podcast

What Garry Shandling’s Jewish Comedy Teaches About Purim

David Bashevkin speaks about the late, great comedian Garry Shalndling in honor of his 10th yahrzeit, which is this Purim.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

Pawel Maciejko: Sabbateanism and the Roots of Secular Judaism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to historian and professor Pawel Maciejko about the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, Sabbateanism, and the roots of Jewish secularism.

podcast

Alex Edelman: Taking Comedy Seriously: Purim

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David is joined by comedian Alex Edelman for a special Purim discussion exploring the place of humor and levity in a world that often demands our solemnity.

podcast

David Aaron: ‘I believe that the Divine is existence and infinitely more’

Rabbi David Aaron joins us to discuss ease, humanity, and the difference between men and women.

podcast

When A Child Intermarries

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to a son who almost intermarried, the mother of a daughter who married a non-Jew, and Huvi and Brian, a couple whose intermarriage turned into a Jewish marriage—about intergenerational divergence in the context of intermarriage.

podcast

David Bashevkin: My Mental Health Journey

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin opens up about his mental health journey.

podcast

Leah Forster: Of Comedy and Community

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David sits down with Leah Forster, a world-famous ex-Hasidic comedian, to talk about how her journey has affected her comedy.

podcast

Yakov Danishefsky: Religion and Mental Health: God and Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Yakov Danishefsky—a rabbi, author and licensed social worker—about our relationships and our mental health.44

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Michael Oren: ‘We are living in biblical times’

Israel is a heroic country, Michael Oren believes—but he concedes that it is a flawed heroic country.

podcast

Rachel Yehuda: Intergenerational Trauma and Healing

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we pivot to Intergenerational Divergence by talking to Rachel Yehuda, a professor of psychiatry and neuroscience, about intergenerational trauma and intergenerational resilience.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Talia Khan: A Jewish Israel Activist and Her Muslim Father

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Talia Khan—a Jewish MIT graduate student and Israel activist—and her father, an Afghan Muslim immigrant, about their close father-daughter relationship despite their ideological disagreements.

podcast

Netta Barak-Corren: ‘I hope that Gaza will see a day when it is no longer ruled by Hamas’

Israel is facing several existential crises—at least three, by Netta Barak-Corren’s account.

Recommended Articles

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

Ki Tisa: The Limits of Seeing God’s Face

We spend our lives searching for clarity. Parshat Ki Tisa suggests that the most meaningful encounters may happen precisely where clarity ends.

Essays

The American Yeshiva World: A Reading Guide

A guide to the essential books that tell the story—past and present—of the American yeshiva world and its inner life.

Essays

10 Ways to Get the Most Out of Your Books

Reading, reading everywhere, but not a drop to be remembered

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

A Jew in the King’s Court: Dual Loyalty in the Book of Esther

The Book of Esther suggests that diaspora is not merely a temporary or anomalous state but an integral part of Jewish history…

Essays

What is the Megillah’s Message for Jews of the Diaspora?

For some, Purim is the triumph of exile transformed. For others, it warns that exile can never replace the Land of Israel.

Essays

The Siddur Has a Lot of Prayers. Where Did They Come From?

Between early prayer books, kabbalistic additions, and the printing press, the siddur we have today is filled with prayers from across history.

Essays

How Orthodox Jews Are Sharing Torah Knowledge Across Denominations

Two programs are already bridging the Orthodox and non-Orthodox divide through the timeless tradition of chavruta learning.

Essays

Why We Need to Live With Radical Laughter This Purim

Brother Jorge asks: Can we laugh at God? We might answer: We can laugh with God.

Essays

Judith Herman Is Giving Voice to Survivors

Dr. Judith Herman has spent her career helping those who are going through trauma, and has provided far-reaching insight into the field.

Essays

Towards the Derech: How Does a Reform Jew Return?

The “way” of myself and other formerly Reform Jews is unclear, but our desire for spiritual growth is sincere.

Essays

How Jewish Communities Can Help Couples Going Through Divorce

Divorce often upends emotional and financial stability. A Jewish organization in Los Angeles offers a better way forward.

Essays

A Letter to Children Estranged From Their Parents

Children cannot truly avoid the consequences of estrangement. Their parents’ shadow will always follow.

Essays

What the 18Forty Team is Reading This Adar

Identity, desire, women in fiction, and more: What we’re reading before Purim.

Essays

What Are the Origins of the Oral Torah?

A bedrock principle of Orthodox Judaism is that we received not only the Written Torah at Sinai but also the oral one—does…

Essays

What Haredim Can Teach Us About Getting Off Our Smartphones

Kosher phones make calls and send texts. No Instagram, no TikTok, and no distractions. Maybe it’s time the world embraces them.

Essays

The Hardal Community Explained: Torah, Am Yisrael, and Redemption

Religious Zionism is a spectrum—and I would place my Hardal community on the right of that spectrum.

Essays

How Archaeology Rewrote the History of Tefillin

From verses in Parshat Bo to desert caves, tefillin emerge as one of Judaism’s earliest embodied practices.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

Divinity and Humanity: What the Jewish Sages Thought About the Oral Torah

Our Sages compiled tractates on the laws of blessings, Pesach, purity, and so much more. What did they have to say about…

Essays

Benny Morris Has Thoughts on Israel, the War, and Our Future

We interviewed this leading Israeli historian on the critical questions on Israel today—and he had what to say.

Essays

Is Judaism Fundamentally Zionist?

God promised the Land of Israel to the Jewish People, so why are some rabbis anti-Zionists?

Essays

Toward a Jewish Theology of Consciousness

The mystery of consciousness has long vexed philosophers and scientists alike. Can God be the answer?

Recommended Videos

videos

Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin: How Torah Gives Us Faith and Hope

In this special Simchas Torah episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin—parents of murdered hostage Hersh…

videos

A Vulnerable Conversation About Shame, Selfhood, & Authenticity with Shais Taub & David Bashevkin

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Shais Taub, the rabbi behind the organization SoulWords, about shame, selfhood, and…

videos

The Hasidic Rebbe Who Left it All — And Then Returned

Why did this Hasidic Rebbe move from Poland to Israel, only to change his name, leave religion, and disappear to Los Angeles?

videos

Is Modern Orthodox kiruv the way forward for American Jews? | Dovid Bashevkin & Mark Wildes

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Mark Wildes, founder and director of Manhattan Jewish Experience, about Modern Orthodox…

videos

An Orthodox Rabbi Interviews a Reform Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue, about denominations…

videos

Joey Rosenfeld: What Does Jewish Mysticism Say About This Moment?

We speak with Joey Rosenfeld about how our generation can understand suffering.

videos

A Reform Rabbi Interviews an Orthodox Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko (Part 2)

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue,…

videos

Mysticism

In a disenchanted world, we can turn to mysticism to find enchantment, to remember that there is something more under the surface…

videos

Torah Study and ChatGPT: How Should Jewish Education Respond to AI?

On this 18Forty panel, we speak with Alex Jakubowski of Lightning Studios, Sara Wolkenfeld of Sefaria, and Ari Lamm of BZ Media…

videos

Steven Gotlib & Eli Rubin: What Does It Mean To Be Human?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast—recorded at the 18Forty X ASFoundation AI Summit—we speak with Rabbi Eli Rubin and Rabbi Steven…

videos

Why Naftuli Moster Left Haredi Education Activism

We speak with Naftuli Moster about how and why he changed his understanding of the values imparted by Judaism.

videos

Moshe Gersht: ‘The world of mysticism begs for practicality’

Rabbi Moshe Gersht first encountered the world of Chassidus at the age of twenty, the beginning of what he terms his “spiritual…