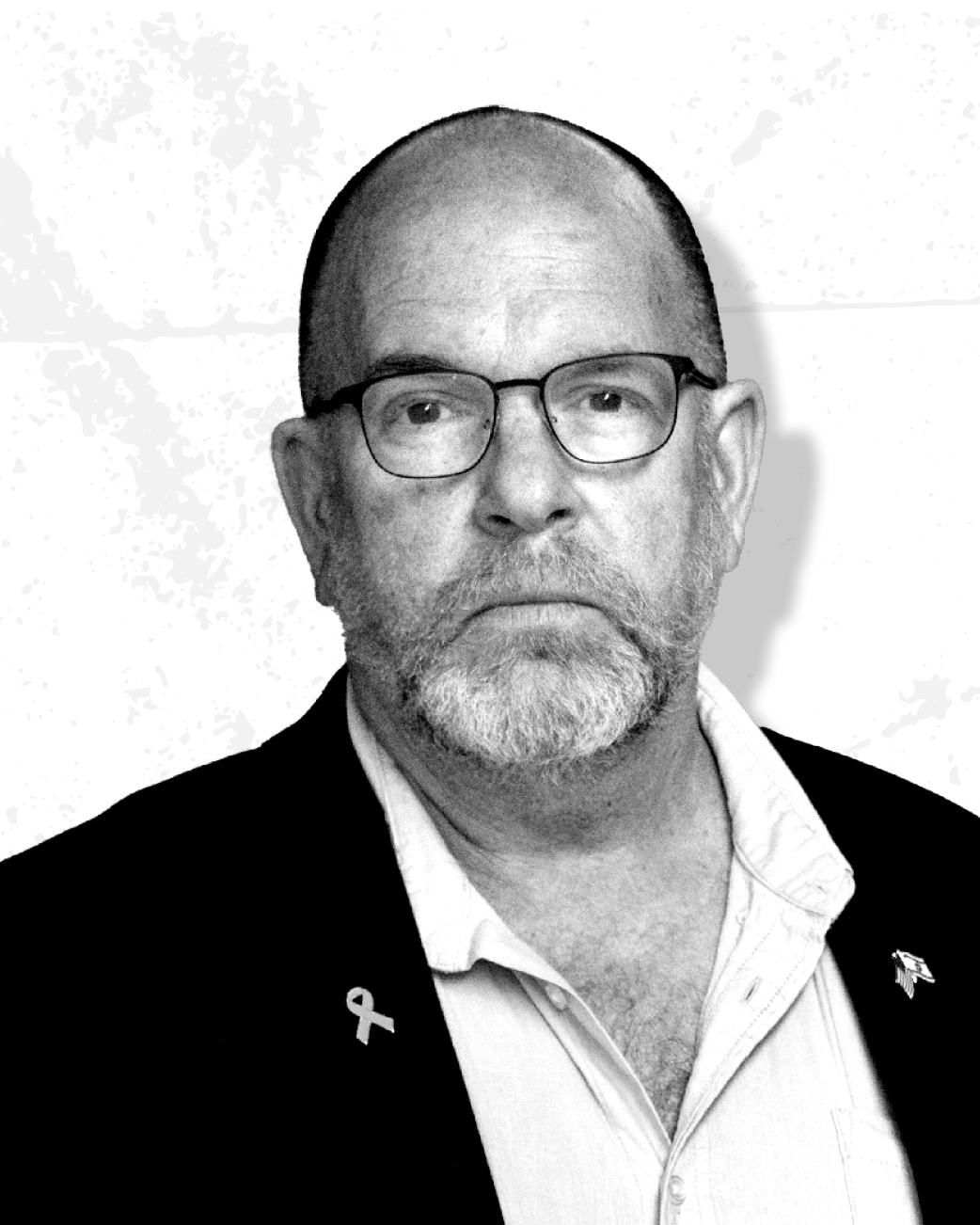

Yoni Rosensweig: How Does Mental Health Affect Halacha?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Yoni Rosensweig, rabbi of the Netzah Menashe community in Beit Shemesh, about the intersection between mental health and halacha.

Summary

Our mental health series is sponsored by Terri and Andrew Herenstein.

This episode is sponsored by Twillory. New customers can use the coupon code 18Forty to get $18 off of all orders of $139 or more.

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Yoni Rosensweig, rabbi of the Netzah Menashe community in Beit Shemesh, about the intersection between mental health and halacha.

It is tempting to sometimes see halacha and mental health as being at odds. But what if, with the right guidance, we could instead understand halacha to be a system that sees the fullness of our unideal circumstances and draws us closer to God in spite of it all? In this episode we discuss:

- How might we enable people who are suffering mentally to live fully halachic lives?

- How can a rabbi apply modern knowledge of mental health to centuries-old rabbinic texts?

- How can we benefit from halacha even—especially—amid our difficulties?

Tune in to hear a conversation about how halacha has more to offer us than we might expect.

Interview begins at 12:25.

Rabbi Yoni Rosensweig is rabbi of the Netzah Menashe community in Beit Shemesh, Israel. Previously, he served as Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Shevut Yisrael in Efrat. Rabbi Rosensweig is the author of several books including the recent Nafshi Beshe’elati on Jewish law and mental health.

References:

נפשי בשאלתי – הלכות בריאות הנפש by Yoni Rosensweig

The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk

David Bashevkin:

Hi, friends, before we get into today’s episode, I just wanted to record a quick note from our sponsor of today’s episode, our friends at Twillory who are offering $18 off all orders of $139 or more, new customers only. And of course, that discount code is 18Forty. I actually have a checklist of things when I am feeling a little down, my mental health isn’t doing great. It’s a five-point checklist. I first check, am I sleeping okay, number one? Number two, am I eating okay? Number three, am I exercising?

Number four and five are a little weird but here they are. Have I gotten a haircut? Sometimes getting a haircut, for me, really, really helps. And number five is I really check, are my clothes falling apart? Are they fraying? And there’s something I feel very restorative about wearing a fresh shirt, shirts that fit, shirts that make sense. And I mean this quite seriously, they didn’t ask me to say this, our friends at Twillory happen to make incredible clothes. I love their joggers, I love their scarf, though people make fun of me that I wear it too often. They make incredible shirts, suits, all sorts of great stuff.

Check them out at twillory.com, T-W-I-L-L-O-R-Y, and use the discount code 18Forty. It really helps us if you use our discount code. It shows that our listeners really care about those who are supporting us. So, it’s a way of really supporting our work. $18 off all orders $139 or more, again, for new customers only. Check them out, twillory.com, and use coupon code 18Forty. Thank you so much to our friends at Twillory for their sponsorship.

Hi, friends, and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast where each month we explore a different topic, balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host, David Bashevkin, and this month we’re exploring mental health.

This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big juicy Jewish ideas, so check out 18forty.org where you can also find videos, articles, and recommended readings. And of course, thank you so much to our friends, our series sponsors, Terri and Andrew Herenstein, Horofei lishvurei leiv umechabbeish le’atzevosom. Their support and their kindness and friendship means so much to me. I am so grateful to have them as friends and supporters.

When it comes to the interplay of halacha and mental health, I have found that there are really two issues at play. One is very often a misunderstanding of the seriousness of mental health, and the other is a deep misunderstanding of the resilience and grandeur of halacha, each of which we will of course explore in today’s episode, but I just want to say a word about both.

As we said from the outset, your mental health is not a side point. Oftentimes, we think of mental health and then push it out when mental health is just as serious as physical health, which can be true. And in some ways, physical health can be more scary, more terrifying. It can feel more real.

In another sense, I think people who struggle with mental health, I think the realness, the intensity of it if you really examine it can be even more overwhelming than something with physical health because mental health is really the lens through which we look out and see the world and engage with the world. It’s clouded. There can be a fog over the very way that you look at and conceive of the world and the way that you look at yourself.

But because maybe the way that it’s diagnosed, or because I believe it is so intrinsically wrapped up in our very conception of self, so we assume that we should hold the keys to, so to speak, snap out of it. And there is a very famous passage in the Talmud, it says it in three different places. Each context is so importantw … That a captive, when you are prisoner, you cannot free yourself from your own prison.

And there is something that is so suffocating and is so difficult with people who are struggling with mental health because you can’t necessarily snap out of it. You can’t just, “Hey, what happened to the old you and all the comments that people say,” which I find when people say that, it only makes it worse.

But your very conception of self is clouded, and because of that, your capacity to make decisions gets clouded. Your capacity to make good and healthy decisions, which is why I think so many people who are struggling with mental health issues are not asking the right halachic questions. We’re not going to rabbis often enough or people who have a real expertise in Jewish law to try to figure out how do I ensure that I am making the right choices with my own halachic observance.

First and foremost, I think it comes from a misunderstanding of mental health. We are subsumed within our own issues of mental health. We are trapped in a prison of our own making, and very often, our capacity to make decisions, ask good questions, it feels too close to us that we don’t even feel comfortable stepping forward and asking a question.

If God forbid someone has stomach problems or a broken leg or any of that stuff, it feels separate from you. So, okay, how does that thing that is separate from me now affect me halachically? But the me in that question is separate in your mind from your leg. But when somebody has mental health problems and say, “How does that affect me?” Well, just think about that sentence for a second. The me is what is most deeply affected, your very sense of self, the way that you operate and transmit in the world.

And for some people, it is so overwhelming, their mental health issues, that it clouds their decision-making. They don’t even think to ask that question. They don’t even think about the implications. And for others, and it could be they’re also suffering very intensely, they don’t allow themselves to think of it as a very real issue. It feels real when I have a cast, it feels real when you have some bloodwork that diagnoses you with something that is very easy to spot as opposed to issues with mental health that can sometimes, especially with the diagnosis, can be much more amorphous. Don’t have the same bloodwork, don’t have the same X-rays, and you feel like you are copping out if you allow that to really shape… You’re giving it realness if you allow it to shape your own halachic observance, and I think that is an absolute mistake.

In many ways, mental health issues are even more debilitating for our religious lives than other issues, and to allow yourself to ask the right questions, to allow yourself to speak to a rav who knows you fully and sees you fully, and knows the issues that come up in a family and your own life and the way you go about the world is absolutely crucial and important.

There is a second issue that I think is worth surfacing, and that is much of our issues related to mental health and the reason why we are not asking enough questions, enough halachic questions, questions related to Jewish law as it regards to mental health is not because of the uniqueness of mental health issues, that’s the first thing we discussed.

I think a lot of it has to do with our misunderstanding of Halacha itself where we think Halacha has different strata. There is an ideal way to do things, and there is a less-than-ideal way to do things. The Hebrew terminology that we use is lechatchila, that is ideal. And then bidiavad, which is literally the words “if it was already done”. Post facto, it’s okay if you do that.

And when it comes to, I guess, mental health questions, because they’re so intimately connected to who we are, I think people don’t like relying on bidiavads in this case, which is a massive mistake. Because I think, for some people, they feel that I don’t want my life to feel not ideal. I don’t want my life to feel like it is bidiavad. I want to live a lechatchila life.

And we have this idealism as it relates to our religious lives, and allowing our own mental health to, so to speak, go in our minds to the lower rung of halacha. We want to just avoid and say “I’m going to power through. I’m going to do it, I know it. I’m dealing with issues whatever they are in my observance because of my mental health issues, but I just want to just power through and grin and bear it. And that is a massive misunderstanding, in my opinion, of how we should be thinking of halacha.

Number one, it is halacha that has the strata. When you are doing something and it is bidiavad, acceptable, that doesn’t mean your life is bidiavad. It is the halacha and the beauty and our faith in the halachic system has a flexibility that allows us to address the fullness of our lives with all of its imperfections. And the fact that we may rely on a leniency does not mean that our life is bidiavad. It does not mean that our life is not ideal.

Our life is exactly as it is through all of the difficulties, through all the work that still needs to be done. But we need to develop the belief, the faith, the emunah in halacha itself that it can address us fully in our lives where we are. And just because someone may need to rely on a leniency does not mean that your life is bidiavad.

And I know because I have felt this at points in my own life that it felt like my entire life was bidiavad, my entire life was not ideal, my entire life did not have the pristineness that I think we associate with that lechatchila living, this is exactly how it should be done. And that’s a misunderstanding of Halacha. It is the flexibility and resilience of Halacha to address us fully in our lives, which is why it is able to survive and guide the Jewish people throughout the generations.

And somebody insisting on an ideal or even a stringency when that is not the right decision for them halachically betrays a lack of trust in the halachic system itself saying that Halacha is not able to reach me where I am. And so much of what we need is to have trust, and almost a loyalty, an emunah, a belief in the halachic system that it can find me and guide me. No matter how broken or lost or distant that you feel in your life, Halacha has a way of reaching out and still addressing you in that place.

And no matter how much a person may be suffering with their mental health, depression, anxiety, halacha didn’t forget about them, Halacha didn’t skip over them. It’s not that their life doesn’t have the dignity of Halacha being able to point them out and embrace them and say we are still for you. That is actually the beauty of what halacha is. It has an incredible amount of flexibility, an incredible amount of resilience of the halachic system.

And we should never feel that because our lives may feel broken, that we, so to speak, broke the halachic system and there’s no way for it to address us in our lives with diminished capacity whatever difficulty that we are struggling with. No, with the right guidance and the right questions, the beauty of halacha, the greatness of halacha is its capacity to address us wherever we may be in our lives.

And today’s guest, Dr. Yoni Rosensweig, has done incredible work on reminding the Jewish people of how the halachic system is able to address them wherever they may be in their lives. And I am centering him not because he is the person you should be asking all of your questions to. He is one person and one approach, but to restore the faith that I think everybody can feel, I know I have felt.

There are points in our life where you feel like you drift beyond the radar of where halacha can reach you, and he does this… What’s so remarkable about Rav Yoni Rosensweig is he does so much of his work on social media, specifically on Facebook where he addresses very serious questions publicly.

And I think what he’s doing, and we talk about this, is he’s not trying to publicize a specific outcome, but he’s trying to publicize the process of allowing people to come forward and find guides in their halachic lives who can remind them and restore that faith in the halachic system. And address you wherever you are no matter how broken, how distant, how diminished your capacity is. That’s how I feel in terms of depressiveness or anxiety. You feel diminished capacity.

And there are times where it can feel very extreme and we say, “Halacha cannot reach me.” And I think so much of this conversation is so important because there is a great sense of misunderstanding in the interplay between mental health and Halacha, about both a misunderstanding in mental health and a misunderstanding in halacha. So, without further ado, it is my absolute privilege and pleasure to introduce our conversation with Rabbi Yoni Rosensweig.

I wanted to begin by talking a little bit about your specific area of expertise. There are rabbonim, there are experts in Choshen Mishpat, there are experts in monetary law and financial law and different areas. You have staked a very specific area of focus of the way halacha interacts with mental health. What drew you to this specific area of halacha?

Yoni Rosensweig:

That’s a question that many people ask me, so I’ll answer you in two ways. The first way that I’ll say is practically speaking, what drew me was just a coincidence of events. In other words, in the fact that I was asked a few shailos in the community, which I did not know how to answer. And looking around, I realized that there weren’t any seforim that really dealt with this issue.

And then I also had a run in with a chavrusa with a psychiatrist, a friend of mine, Dr. Harris, who I eventually wrote my book with him, Nafshi Bishe’elati. So, I went to him, and I said, “Let’s learn together and see what we can come up with.” And the goal was to just answer a few shailos, but very, very quickly I realized there was an entire field here that needed discussion.

So, in terms of shall we say the historical story is that. But in terms of the more essential question that you’re asking, my nature is that when I see an area of halacha that I feel needs to be more developed than it is, I gravitate to that very, very quickly. It really interests me. All these points of connection between, shall we say, the modern world and the halachic world are very much of interest to me. And developing a response to that that is steeped in sources, that is steeped in tradition, that can bring those two worlds together is of great importance to me.

David Bashevkin:

Let me ask you a foundational question about your philosophy and how you approach things. When it comes to physical limitations, if somebody does not, God forbid, have arms, they’re unable to put on tefillin. There are physical limitations that we know that we have. We also have emotional limitations in what we have. Do you believe that everyone has the emotional capacity to live a fully halachic life?

Yoni Rosensweig:

It’s a bit of a trick question, so I’ll answer it in two ways, okay? The simple answer to your question is no. In other words, I do not believe that all people have that ability. You could say that someone who was born just mentally deficient does not have that ability. But even if they were born fully capable, if God forbid, they were abused as a child, or God forbid, other things happened to them, then they certainly, at some point, developed significant boundaries for themselves where they can’t go beyond those boundaries. They can’t go beyond their obstacles that they have basically created for themselves in order to survive, and there are definitely limitations for them.

However, the reason it’s a trick question is because I would not say that that individual is not living a halachic life. They’re living a halachic life within the boundaries that are relevant to them. If someone has a lifelong chronic physical ailment that precludes them from fasting on Tisha B’Av and Yom Kippur, and of course, the minor fast, would you say that they’re not living a halachic life? I don’t think you would.

David Bashevkin:

They are, absolutely not. The Halacha informs how we adapt that, and somebody whose emotional capacity precludes them from living a halachic life is still living a halachic life if they use the right principles. That’s essentially your answer.

Yoni Rosensweig:

Exactly, exactly. And this is an important answer not just because… And I think it’s obvious once you say it, but I think because that a lot of people who are suffering from mental health challenges don’t see it that way. In other words, they feel, whether it’s self-stigma, or it’s stigma that is put upon them by society, that they are somehow at fault, that they are somehow deficient, and that they’re not able to lead a proper halachic life.

One of the major things that I have been doing is to try and explain to individuals… I’m not talking about the society, I’m talking about even the individuals who are dealing with the challenges, to explain to them this is not your fault, and you’re not betraying Hashem, and you’re not betraying Halacha when you’re doing the things that you need for your mental health. This is what .. wants for you.

In fact, on some level, it would be the opposite. If you weren’t doing these things, you would be betraying Halacha just as the person who has a cardiac issue, and a doctor tells them they must eat on Yom Kippur. And if he does not do that, that is a violation of halacha. In the same way, the person who has the anorexia, or the depression, or whatever it is, they need to also care for themselves, and not doing that is the violation. Not doing that.

David Bashevkin:

A lot of the words, a lot of the differentiation we have within the world of mental illness, we sometimes struggle to find diagnoses or descriptions of this in rabbinic literature, in the Gemara, in Rishonim. Anxiety disorders, mood disorders, the long-lasting effects on trauma. I’m curious what concepts and individuals do you draw upon who you think led the way to allow the specific type of emotional health, which is a lot more…

There’s an element, I wouldn’t call it subjective, but it is less almost verifiable than many of the classical… You could take a blood test and you know exactly what the person is struggling with. That’s not always true of psychological health. So, I’m curious, what are the concepts that you draw upon to evaluate when a psychological disorder should have clear halachic consequences?

Yoni Rosensweig:

This is actually a question that deserves a really long answer, but I’m going to try to make it very, very succinct for the purposes of this session. So, I will say like this. When you look at Chazal, when you look at the Gemara, the concepts that you see, and the main one that people know is w. The concepts that you see describe a very small portion of what we consider to-

David Bashevkin:

And just to translate, I’m sorry to jump in, the word shoteh, what do you think the plain reading of the word shoteh? Somebody-

Yoni Rosensweig:

I would say mentally incompetent.

David Bashevkin:

Mentally incompetent, okay.

Yoni Rosensweig:

That is referring to a very small portion of what we today consider to be part of the mental health world. And if you want to give it a name, it would be like mania or psychosis. Meaning individuals who really do not have a firm grasp of what reality is. So, in other words, the rabbis, and the rabbis were a reflection of their society, of the world at the time, really only recognized the extremes. The really extreme presentations of mental health. That’s what they knew, that’s what they realized.

Everything else was just like, he’s a bit quirky, he’s a bit more organized than I am, he has OCD. He’s more stressed than I am, not that he has anxiety. It was all put to personal differences, et cetera. Today, we are much more discerning in certain ways, and we have much more of those things.

So, it’s a slow process, once again, not just for the rabbis, but for the world in terms of really understanding that mental health can be defined and can be discussed even in those presentations that are not in the extremes. Now, once we get into that, your question, of course, becomes much more important and much more acute. If we’re not going to talk about the extremes, how do we make sense out of all that mush, you could say, in the middle? Or some people tell me, “How do you know he’s not just lazy? How do you know he’s depressed? Maybe he’s just lazy.”

It’s a good question, certainly, and the DSM, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, which is basically the bible of psychiatry has tried to put forth criteria in order to manage that, so to speak, mess that’s in the middle and to make sure that we are not diagnosing cases that are not diagnosable or shouldn’t be diagnosed and vice versa. With all that said, it’s still messy. No one’s saying that it’s not.

Now, what I had to do when I first came to this topic was to make sense, from a halachic perspective, of the mess. And no, I’m going to give you in short form what I came up with. With regards to choleh sheyesh bo sakana, for example, with regards to someone who has been in a life-threatening situation, the definitions are relatively clear. You can imagine for yourself someone who was suicidal, someone who might hurt themselves or other people, who would be considered a choleh sheyesh bo sakana. There are other examples, but that’s a classic one.

Choleh she’ein bo sakana, someone who is not considered in a life-threatening situation, that was more complicated, much more complicated. But in discussion with several poskim, my feeling is that you can definitely say that someone whose mental health affects their functionality. So, in other words, that because of the depression, they can’t get out of bed, for example. Because of the depression, they can’t go to work, meaning it’s affecting their functionality. That would be considered the equivalent of a choleh, someone who’s sick in physical health terms in Halacha. And then we could apply whatever criteria, applying Halacha to a physical choleh, someone who’s physically sick, to someone who is mentally so as well. That’s in short, that’s in short.

David Bashevkin:

In history, in the history of response to literature and rabbinic texts that I’m sure you draw upon, are there specific figures from Jewish history who really could be credited with providing more language in developing the halachic impact in Jewish law? That emotional mental health the way we conceive of it today, and its relationship to halacha. Who do you look at, as the earlier writers, not contemporaries, who wrote about this and really began to give the language to mental health as a serious halachic category?

Yoni Rosensweig:

I will mention names, okay? But it’s hard to find. Why is it hard to find? Because, just for the sake of the discussion, we can distinguish between psychiatry and psychology. Psychology is much more unclear. It’s definitely much more of a problem because theories, everybody has theories about why a person does this or does that or does the other, and it’s hard to choose one theory from another, and mostly that’s what existed in the world.

Psychiatry, as a science that is more acceptable and more recognized, really only came into its own in the ’80s. Therefore, really until the ’80s, we don’t have much of a structure, much of a foundation that poskim, the rabbis could really sink their teeth into. And that’s also really talking about something from the last 50 years.

Nevertheless, there are those who tried to create such foundations and such principles. Rambam, Maimonides, of course, is a major one. He definitely, relatively, once again, discusses quite a few things here and there.

David Bashevkin:

What comes to mind? I’m curious. I’m surprised that your first person was Rambam.

Yoni Rosensweig:

The reason I mentioned the Rambam, I’ll explain why, is because if you go to a mental health professional today and you ask him to talk about what depression is, the answer you’ll get will be a description, meaning it will be symptomatic. The person will say, “Oh, depression. Depression is someone who…” And then they’ll describe: can’t sleep, can’t eat, can’t get out of bed, maybe has suicidal thoughts.

They’ll describe a bunch of symptoms, and they will explain that those symptoms are the classic definition or the classic representation of someone who is suffering from depression. The Rambam did something similar, that’s why I mentioned the Rambam because he also spoke in symptomatic language. For example …

David Bashevkin:

Second chapter, ninth Mishnah, yeah.

Yoni Rosensweig:

The Mishnah mentioned someone who puts out a candle because of ruach ra’ah, which it’s a question how to translate ruach ra’ah. An evil spirit you might say. Certainly, Rashi, another contemporary of the Rambam, almost contemporary, translates it more as a demon or something along those lines.

But Maimonides, the Rambam explains ruach ra’ah as depression, and he actually describes the presentation of depression for such an individual. Someone who doesn’t want to be in the light, who keeps away from other individuals. He gives a little bit of a clinical presentation of it. And that’s fairly modern, meaning it’s a fairly modern thing to do is to explain something in that way. So, therefore, I mention Maimonides first.

Look, I will say this, when you look at all the literature, pretty much up to the 19th century, and most of it is in responsa, you will see that people do mention mental health, but they almost never describe it. Meaning I once collected all the responsa that I know on these issues, from the early times. It came out about 40-45 responsa, and I came to my friend who’s a psychiatrist. I said, “Let’s try to, so to speak, diagnose these individuals retroactively.”

It was almost impossible to do because a mental health professional relies highly, greatly, on history. They want to know what happened to the person, they want to know how they’ve been reacting to certain things. They want to know what’s going on with a person. Just telling me, “He talks just gibberish.” That’s one thing. It could be a million things if he talks gibberish. It could be this, or that, or the other, so therefore, I don’t know what it is. Therefore, it’s very, very hard to tell, but there are few, so to speak, beacons of light in the darkness.

David Bashevkin:

Are there any other beacons that you want to mention aside from Rambam? Because I love that example, I thought that was fascinating.

Yoni Rosensweig:

There’s one teshuvah, of the Tosefists, actually, from that time period, where they actually describe very nicely someone who is probably psychotic. And they describe it. It really gives a full description of the person and what he thinks and how he thinks that there are little dwarves living in his stomach and this and that. They go into a whole description, it’s fascinating.

David Bashevkin:

Do you know where we could find this responsa?

Yoni Rosensweig:

If I remember correctly, it’s the 87th teshuvah, but I have to look it up to tell you the exact … But yes, I could send you the teshuvah, it’s fascinating. I should mention one more, but that’s really jumping much ahead.

David Bashevkin:

Jump away.

Yoni Rosensweig:

The Chasam Sofer, so Rav Moshe Sofer in the 19th century, he’s the first one to write a responsa about the question of sending an individual to a mental institution, and I guess those also didn’t really exist probably until a certain point.

David Bashevkin:

Certainly, ones that kept kosher.

Yoni Rosensweig:

Right, right, right. So, that’s the question in the teshuvah. The question there is about keeping kosher, and what’s interesting about that is that most of the responsa… We have to understand once again, because all they knew in the past was more the extreme examples, most of the topics they were talking about were about mental competence.

In other words, it was the competency of an individual to give a divorce. It was the competency of an individual to receive a divorce, to do transactions, et cetera, et cetera. It was always about the competency of an individual.

David Bashevkin:

The baseline of what is considered an aware person for basic transactions and awareness.

Yoni Rosensweig:

Exactly.

David Bashevkin:

But all the middle ground of the language you used of a choleh she’ein bo sakana. Somebody who maybe it’s not life-threatening, it doesn’t take away all of their competencies, but definitely weighs and has psychological implications. That was under-discussed in a way.wwww

Yoni Rosensweig:

Right. To put it differently, these individuals were outside the halachic discourse because they weren’t competent, or they were depending on how we ruled. But we never really thought, or there was never really much discussion, much robust discussion about how to enable a halachic life for such individuals who were suffering mentally.

And once we started talking about the gray, then that became part of the discussion. Here we see the Chasam Sofer may the first one, Rav Moshe Sofer,d trying to figure out, “Okay, this kid, I can send him to an institution where he’s going to eat treif, violate Shabbos, but at the end of it, he might be competent enough to keep the halacha, to keep the laws. So, is it worth it, so to speak, to make that sacrifice, to send him to this institution, have him there for a few years, gain the mental competency in order to emerge from there and rejoin the Jewish community?”

That’s a different kind of question which, until the 19th century, basically didn’t exist. And both the tools and the conceptual framework needed to be in place in order for such a question to surface amongst halachists. So, that’s why I think also that’s a very important responsa.

David Bashevkin:

One thing that makes your work remarkable is not just the area that you discussed and focus on so much, which is the interface between Halacha and mental health. But aside from the area, it is where you have these discussions. And one thing that I think is really quite, I would say, courageous and commendable because I know what it feels like to be in the public square, is a lot of the discussions, a lot of your ideas you share on social media, specifically on Facebook where you have a very big presence.

I wanted to know, your decision to share widely on Facebook, I could only imagine has been criticized. And one of the criticisms I could imagine, this is just me as an individual thinking, is the subjective nature of mental health as opposed to where you have a very clear diagnosis when it comes to many other illnesses. Not to say that we don’t ever have clear diagnoses with mental health, but there’s a lot more interpretive work that maybe a doctor’s involved in.

And I wonder, for you, how you negotiate between you’re sharing publicly, and how do you negotiate between the subjectivity of the halachic advice and it’s responding to something that is so intimate in the most real sense as part of your own interiority. How do you balance that while still being able to share publicly and maybe even more largely, what is your specific goal in sharing publicly at all?

Yoni Rosensweig:

That’s a great question, one that I have thought about a lot, and I have more or less created for myself certain guidelines. So, I’ll talk to the last question that you asked, okay? What’s my goal? My goal in sharing really is only one goal, and that is to raise awareness. The entirety of my activity on Facebook in this regard is meant to raise awareness, or I’ll say almost the entirety, with one exception, which I’ll mention in a moment. But generally, that’s the goal.

David Bashevkin:

Raise awareness for what?

Yoni Rosensweig:

For two things. First of all, for how real mental health issues are in general, without even the Jewish or halachic aspect. Just to raise awareness about the importance of mental health. But specifically, to explain why my work is important and why it is important that people within the religious community and the orthodox community receive the care, the halachic care that they need.

To understand that is also a very, very big thing because people don’t always realize like, “Okay, what does it matter if there’s a rav who’s answering these questions or not answering… Isn’t the mental health of the individual what’s most important?” And sometimes I get people like that who say to me, “Why are you making it so complicated? Why are you telling people, oh, you can do this, you can’t do that, et cetera, et cetera? Why go into all these little niches? Just take care of yourself.”

David Bashevkin:

Take care of yourself, end of story. Every response will be one line.

Yoni Rosensweig:

Right, be healthy.

David Bashevkin:

Take care of your mental health, be healthy, yeah.

Yoni Rosensweig:

Right. So, my answer to that is that you obviously don’t understand what an Orthodox person is or how they think. Someone who lives within an Orthodox framework, that framework is important to them. And if they’re not keeping it, they feel like a failure. They feel like a dismal spiritual failure. They feel like they’re betraying themselves, they feel like they’re betraying God, they feel they are betraying their Judaism. Their whole belief system falls apart.

Judaism because it’s so legalistic, and those who are not orthodox don’t always understand it, but because it’s so legalistic in nature, it is a framework that encompasses your entire life. If your Judaism is falling apart, your life is falling apart. Therefore, what I want to try and create for people is not a system where I would say to them, “Everything’s fine, your health comes first,” and just be as lenient as possible. I always say it’s the opposite. I try to be as stringent as possible within the leniency. In other words, I want to create, yes, a general standard that they can care for their mental health, of course. But within that, to be as stringent as possible to maintain their spiritual commitments, and so that they feel like they’re still part of the community.

We talk a lot about stigma. Stigma makes you feel like you’re not understood or like people are looking down at you or they don’t think that it’s real or whatever it is. There could be also be stigma from the other side. If you feel like you’re a second-class citizen in the Jewish world, if you feel like everyone else is keeping the Halacha, keeping Jewish law but you’re not, you also feel stigmatized against. You feel like why should I go to shul? I’m not welcome there. No one thinks that I’m as good of a Jew as they are, et cetera, et cetera. And I’ve heard this. I’m not making this up, I’ve heard this.

So, therefore, what we need to do, and this is part of my goal on Facebook, is to explain why it’s so important that rabbis be able to understand and tackle questions of mental health. It’s not just to answer a specific question like some nitpicky issue. No, it goes to the nature of the challenge for individual. They don’t want a leniency, they want balance in their lives. That’s what they want, that’s the key word. They want to be able to balance their physical health with the halacha and their mental health with the halacha. They want both, it’s important to them to have both.

So, that’s what I try to promote on social media. And one more point, just to answer your question, this is why I almost never post answers to the questions. What I mostly do is I present the questions. I say, “Someone came to me and told me so and so and so. Someone came to me and asked me this and this question.” I rarely post the responses that I give exactly for the reason that you asked me at the beginning because aren’t I worried that the responses will be taken out of context. Aren’t I worried that what’s right for one person is not right for another person?

And I am worried about those things, especially in mental health where everything is so subjective and so individualized much more than physical health. So, therefore, because of that, I rarely, rarely share the responses that I give to these individuals. My goal is only to raise awareness, so I share the questions that I get, and I make, I would say, general or philosophical or theological points about those questions.

I rarely start delving into the halachic of how I answer the specific individual. The only exception to that is when I think that a certain question has more clarity to it, or when I know that many people are searching for the answer to this question. For example, anorexia and Yom Kippur, which I know many people are more or less in the same boat, need the answer, need the response. And you can more or less, with certain caveats, give a general response that answers people’s concerns without having the problem of making an error in terms of how wide the publication is.

David Bashevkin:

I very much appreciate. I love the term that you mentioned halachic care, where part of what’s essential to a person’s health is actually the ability to have Halacha address them even in their difficulty. Specifically, perhaps, through their difficulty. I would add a third reason why it’s so important, and that is for the integrity and almost our collective faith in the halachic system itself.

It inspires me to know that our halachic system can address the humanity of our lives even in the most dire circumstances. You already mentioned one example, which is anorexia on Yom Kippur. I am curious if there other… I’m curious if there are other… I’m not asking for the answers. I’m going to abide by that. We have quite a few listeners, we’re not asking people to find halachic guidance, guidance in Jewish law from the 18Forty Podcast. But I’m curious what are the central themes that arise? What are the central most common questions? The patterns of questions that you know you get around the clock. I could imagine and it comes as no surprise sadly, anorexia and Yom Kippur. What are the other most common questions that you see people reaching out about that you would most commonly address?

Yoni Rosensweig:

I’ll answer your question, I just want to say that I do appreciate what you said just now, and I think it’s absolutely true that the integrity of the halacha, that’s something that people themselves need to hear. In other words, like I said, the people with the mental health challenges. A lot of them believe that there are no answers to these things.

They say, “Who’s going to allow this for me?” Whatever it is, and I’ll give you some examples in a moment. But they’ll say, “Who would ever allow such a thing? No way, yeah? No way. So, all I have to do is I have to suffer.” And what people do is they do one of two things. They either keep the halacha and suffer until they break mentally.

David Bashevkin:

God forbid.

Yoni Rosensweig:

Or they decide that the halacha’s not for them, and they will just say, “Okay, well, I can’t possibly live this sort of life, so I have to be not religious.” And I cannot tell you, really, I cannot tell you how many people have written to me, “I’m not religious anymore. If I would have known you 10 years ago, my life would have been different.” All because of this stuff because people just believe it’s not compatible.

David Bashevkin:

People want to know that Halacha addresses my life and my humanity, and that’s why I think your work is so incredible. It inspires my faith, not in people, and not in you as wonderful as you are, but in halacha itself when I see halacha addressing… But answer that question. So, what are the questions that are most commonly asked? What are the questions that you would want people to know that, yes, halacha addresses this?

Yoni Rosensweig:

As you said correctly, eating orders and fasting, obviously, right? But then everyone can already think that those things come up. I think maybe the two most famous things in mental health are maybe that question and OCD questions. OCD is also well-known, and people assume, oh, yeah, washing hands, and there are plenty more by the way.d

David Bashevkin:

The Steipler famously wrote quite a bit in those early years in Bnei Brak about people struggling to get through their prayers. And they were worried I didn’t have enough kavanah, enough intention, and they’ll say a line 20-30 times. And he addresses those people and gives them very often very solid almost therapeutic guidance on how to feel a sense of religious integrity and sense… Give me a few other areas that come up quite frequently in your work.

Yoni Rosensweig:

Shabbos and using your phone, that’s a big one. The reason is, and I know that it’s not readily apparent to people. The reason is because people have coping mechanisms, and a major coping mechanism today is the phone. Meaning either listening to music or watching something. For someone with depression, for someone with anxiety, for someone with an eating disorder, for someone with borderline personality disorder. Is it okay if I give an example? I don’t want to shock your listeners.

David Bashevkin:

Absolutely, please.

Yoni Rosensweig:

Okay, so I’ll just give one example. I know that this example is extreme, but I’m giving it so people understand-

David Bashevkin:

We’re making a general disclaimer. This is not where people should be turning for halachic guidance. You should find a rabbi, but you should know that rabbis like Rabbi Yoni Rosensweig do exist probably in your area. And you should always have the confidence to ask questions, that’s what this is about.

Yoni Rosensweig:

Absolutely.

David Bashevkin:

But give me your example, please.

Yoni Rosensweig:

So, for example, there was a young woman who looked me up, and she said to me that she has OCD, and she wanted to know how to use her phone on Shabbat in order to deal with her, so to speak, intrusive thoughts. Now, someone listening to that question might say, “Okay, intrusive thoughts, I mean it doesn’t sound so bad. What’s the big deal? Why does she need to use her phone on Shabbat, that seems extreme?”

I’m already used to these questions, so I asked her a few questions. When I asked her, the response that I got, this was the full story. She told me that her OCD was such that she was using gallons of bleach on her body every single day, and she was cleaning herself with that bleach and it was causing burns all over her body. And she was at death’s door at one point, and the doctor said that if she continued to do this, that she would die.

So, therefore, when she was calling me, she told me that she wasn’t using as much bleach anymore. She was still using it, but she wasn’t using as much anymore. So, then you have to understand that a lot of these behaviors they lead to literally pikuach nefesh, they literally lead to something that’s life-threatening. Because the OCD doesn’t sound so bad, but someone who’s using bleach to clean their body, it’s pretty bad.

Now, what does the phone do? Just to be clear, so why does she need to use her phone? Using a phone in that situation, in that scenario, is something which allows the person to leave their thoughts behind. It distracts them, and that distraction is pivotal sometimes for someone who’s suffering from depression or OCD or anxiety because they live in their head.

A lot of times those individuals they live inside their head and they’re torturing themselves constantly, constantly, with different kinds of thoughts. So, the ability to disconnect from all that is definitely could be very, very significant. And yes, long-term, I’m not saying in the short term, but long-term, could be the difference between life and death sometimes. Meaning if the individual is able to leave that destructive thought pattern behind, yes, it could sometimes also be the difference between life and death.

So, therefore, when people ask me about a phone and using a phone on Shabbat, I’m not saying I take it lightly, but I don’t take their question lightly either. It’s definitely something that we need to consider, and for the right person, to allow whatever needs to be allowed.

David Bashevkin:

Any other questions that jump off at the top of your head? We mentioned OCD, we mentioned eating orders and fasting, and we mentioned Shabbat and phones. What are some of the other common examples, questions that have been posed to you?

Yoni Rosensweig:

Niddah questions. So, niddah is a woman who’s menstruating, and for those who don’t know, she is not allowed to be in physical contact with her husband on average 11 to 12 days of the month as a result of the menstruation. Someone who is suffering from depression might need a hug, and if it’s the husband who needs a hug from the wife, or a wife who needs a hug from the husband, and they’re not allowed to be in physical contact, that could many times be the difference.

Once again, I mentioned functionality before. Getting that hug might sometimes be the difference between being able to get out of bed and taking care of the kids and making dinner, and between not being able to do any of those things. So, it might seem to someone like, “Oh, come on. Surely, there are other things,” but it’s not true, not for that individual. For that individual sometimes it’s really not true.

That’s what they need. That’s what their coping mechanism. That’s what gets them out. That’s what gives them the koach, the strength to move on with their lives, right? So, that’s another question that I get asked very often. Very often I get asked that question. It’s not a rare… I know people always think because, once again, I know because when they ask me the question they say, “Who asks these sorts of questions?”

And I also thought to myself the first time I got it, I said, “How many people really have this need?” I can tell you now from years of experience, so many people who suffer from depression have this need. And once again, it’s not just a need like I’ll feel better if I get a hug. It’s more than that. It’s literally the difference between them being able to function during the day and not being able to function during the day.

So, we’re talking about, shall we say a therapeutic hug. It’s a hug that carries with it significant weight shall we say. And once again, I’m not saying that we allow it in every single case. We have to think about the case and what other options are out there and depending on the individual.

But yes, I spoke to many rabbis who say this also. I know people don’t always know my name. Everyone should know that for the book, which is soon coming out in English, I actually spoke to 14 different halachates here in Israel and also in the US, and ran any complex question, any question that I felt was, so to speak, above my pay grade, I didn’t have sources for, ran everything through well-established halachists.

David Bashevkin:

Are you comfortable mentioning any of their names? I actually don’t even know who your rebbe, what world you emerged from. I first bumped into you on social media. We have, I think, some mutual friends who urged me to reach out to you. I’m curious, is there somebody who you consider your rebbe, your mentor when it comes to matters of psak, of Jewish law?

Yoni Rosensweig:

I learned for eight years in Yeshivat Birkat Moshe in Ma’ale Adumim, so Rav Nachum Eliezer Rabinovitch that’s how, if you know that name-

David Bashevkin:

I absolutely do. One of the real heroes of the Jewish people. I learned at Ner Yisroel. He was one of the cherished students of Rav Ruderman, I believe. A renowned expert in matters dealing with rov, majority, how we calculate them. And his works, which are not so well-known, but he is a giant of giants.

Yoni Rosensweig:

Absolutely. I could talk about him now for hours, but he was really a giant. I was zoche, I merited to be at his side for several years and to learn from him … To learn how to pasken, and to ask him questions also for the book. Towards the end of his life, I was able to ask him a few questions.

He is and always will be my rebbe even though he’s passed away. But beyond that, there’s no problem mentioning the names because they’re all mentioned in the introduction to my book, it’s not a secret. I assume that the names that your listeners may recognize the most are Rav Hefter and Rav Willig from YU who I managed to also ask many shailos for the book, which I was very, very happy about. Rav Osher Weiss I’m sure you would know.

Swo, a few others who are Israeli.wwwww Rav Re’em Ha’Cohen, who is the rosh yeshiva of Otniel, Rav Baruch Gigi rosh yeshiva of Har Etzion, Rav Henkin before he passed away, I was able to ask a few shailos to Rav Yaakov Ariel, who—

David Bashevkin:

Sure, tell our listeners again, your book in Hebrew is called Nafshi Bishe’elati. Iat’s being published, I believe, by Koren in English. Could you just tell our listeners so they can keep an eye out for it? What is the name of the book in English and when is it coming out?

Yoni Rosensweig:

I actually don’t know. I actually don’t know.

David Bashevkin:

You don’t know either of those? You don’t know what the title is going to be?

Yoni Rosensweig:

No, that’s the one I don’t know. When it’s coming out, I actually have a better idea. The title of it I wasn’t sure. Since I know that you know Hebrew well, so therefore, I know that you can understand the play on words that Nafshi Bishe’elati has for a book on halacha and mental health.

David Bashevkin:

Explain the play on words.

Yoni Rosensweig:

… Esther is basically pleading for her life. So, she tells Ahasuerus the king, I’m basically holding my life in this question. I’m saying, “Nafshi bishe’elati.” My life is depending on this question, but the question that she asked was whether he would spare the Jews and spare her, and act against Haman who was trying to destroy them, so that was the original context.

But the word nefesh in Hebrew holds many, many different connotations. And while there she meant her physical life, nafshi bishe’elati, b’riut hanefesh is actually translated mental health. So, nefesh also has the connotation both of mental and spiritual really. And the word she’elah is not just a question, but also a shaila, also a responsa, meaning also a halachic, a Jewish law question.

David Bashevkin:

And almost staking your claim for your nefesh through she’elos. Through asking questions, which is really all the work that you’ve done. I have one other question. Before I get to it, I was just wondering because you whet my appetite a little bit. Could you describe a little bit in your interactions or a story or just some anecdote that explains why Rav Nahum Rabinovitch was so gifted or unique, specifically in the area of wedding Halacha to the interiority of human experience? Because I assume most people, for sure in the States, have really not heard of him, though I think some of his works have been recently published in English. But what is it about him and his approach to Toras that explains why he’s so unique in this area?

Yoni Rosensweig:

My rebbe used to say he doesn’t have a great memory. What he meant by that was he wasn’t one of those rabbonim who name-drops. I know many rabbonim … I’m not saying this to his detriment. I’m saying it as a praise. You hear in everything he says he can tell you where it’s from. He tells you-

David Bashevkin:

Every source, every yeah.

Yoni Rosensweig:

Every source, everything … My rebbe was not like that. He would speak and he would tell you, “This is the halacha.” And when you said, “Why?” He would give you a svara. He would say why he thought that was true. And many things I never really knew when I spoke to him what the sources were. But he had learned it, he just didn’t always know how to place it.

When I afterwards did my own research, every time I found what he was talking about. Every single time he would say, “Yeah, people say this.” I’d say, “Who said this?” “I don’t remember exactly, people say this,” and then I would find it. He learned a ton when he was younger. I would say that he breathed halacha. In other words, he breathed halacha, and he breathed the spirit of halacha. In other words, he may not have been a quoter, but he understood in a deep way that which he learned. And he lived it, and he taught it through that, I would say, personal connection that he had to the spirit and the lifeblood of Torah. In other words, he didn’t need a source because the sources were there.

David Bashevkin:

He almost subsumed this intuition and embodied the spirit. An incredible person I never merited to meet. I have one question, some of your responsa get a fair amount of criticism and controversy. Maybe I am overdoing it, maybe you don’t really feel it, but there are times where you can discuss something that is very weighty in ways that maybe other rabbis do not appreciate or other rabbis strongly disagree with you.

I am curious, for you, how you react on a personal level. I’m almost asking about how you take care of your own mental health when you are assuming halachic responsibilities that must weigh a great deal on you. Especially when your very work and service can oftentimes be the very point of criticism that you are getting from rabbis that I assume you respect and that you appreciate. But getting criticism sometimes from your colleagues can be the most painful thing.

I’m curious, how do you respond to criticism? How do you respond to people who see the work you are doing and says, “Who gave you the right? Why are you the person who are doing this? I disagree very strongly with what you are saying?” How do you generally respond to criticism of your work?

Yoni Rosensweig:

First of all, may I say that, of course, I welcome any sort of machloket l’shem shamayim, any sort of disagreement. I have absolutely no issue with it in and of itself as long as the attack is on the work and not on the person. And sometimes I do get ad hominem attacks. I will freely admit that those hurt me. I am offended when someone doesn’t attack the work but attacks the individual and claims that I know, “Who is this guy,” so to speak, et cetera, whatever it is. Those sorts of attacks, or calling me by name, or people say … this or that, which doesn’t happen often but has occurred once in a while.

So, definitely, when the attacks are personal, then I take it personally. But I have no problem with machloket, with a disagreement that is l’shem shamayim, that is there to really understand what’s being said, and if someone doesn’t agree with me, that’s fine. With all that said, the way I take care of myself both personally and publicly is that I never… This is a rule for me. I never publish a 300-word post on a halachic issue without having written 3,000 words on it for myself halachically.

In other words, I first do the work halachically, meticulously on every single topic. And I make sure that if anybody ever has a question, I have a file to send them. And sometimes the file is 10 pages long, sometimes it’s 100 pages long, whatever it is, but I have done the work. And then they can still disagree with me if they want, and I have no problem with that.

But I have never just shoot off the cuff. I say, “Okay, this is what I think, this is what I think, this is what I think.” It’s always going to be backed up by personal work that I have done, and also with the book. Even though I ask the rabbonim as I mentioned before that I went to halachates and I asked them, I never did that before I did my own work. It was always important for me to do my own work first, and then after I’ve done my own work and I’m comfortable and I’m confident that what I’m saying is correct, then with all that, I didn’t want people to just rely on me.

I wanted them to have formidable halachic names at the forefront. And so, I went, and I asked people, “So, for all these rulings, I have, I think, enough backing that I feel comfortable enough to talk about them.” And of course, once again, if someone wants to discuss, they can discuss. But most times, most times, I have realized that when people do attack me, and if they actually do eventually reach out to me, and even if they have a strongly worded response, once they received my files, once they received my work, once they see what I did, they realize that I’m a serious guy. And that they can still disagree, but they understand that we’re on the same side. And that I’m not trying to undermine Halacha-

David Bashevkin:

God forbid.

Yoni Rosensweig:

… or trying to pull people away from keeping … It’s exactly the opposite. My entire work, my entire work is to be mekarev people. My entire work-

David Bashevkin:

To bring people closer to Yiddishkeit and to halachic observance.

Yoni Rosensweig:

Correct, the entire thing.

David Bashevkin:

Because you mentioned sometimes you feel hurt, and I can imagine in the work that you do and the responsibility that you subsume, that it could be absolutely exhausting and taxing. You take a lot of responsibility on yourself. What do you do to actually address your personal mental health? Not to respond to detractors, which is important, but when it weighs on you, you can feel hurt at times. And I’m sure the responsibility itself even when you issue a controversy-less response, there’s a responsibility anytime you put something out there. How do you address your own personal mental health?

Yoni Rosensweig:

You’re right, you’re right. So, I would say three things. One is I have family, thank God. My wife and children support me. Obviously, at least for me, there’s nothing more therapeutic than spending some time with the family and all that. The second thing that I would say is sometimes I take a break. There are times when I feel like I’ve been too much on social media, and I just need a break. I need a break of a few days, et cetera, and that’s for sure.

But the last thing, which is maybe most important, and I think all therapists know this and rabbis should know it too is therapists need therapists. Many times, yes, I think that any rabbi who is dealing with mental health issues needs someone that they can talk to and that they can sometimes go to and make sure that they are caring for their emotional needs, their mental health needs because these things can weigh on you.

We have a war going on here in Israel as you well know, and I get relatively a much higher number than usual of questions that have to do unfortunately with suicide and suicidal ideation. People who are very, very stressed and they can’t see this, they can’t put up with it anymore, they just want to end it, things like that. When you hear story after story after story about people who are so far gone that they just want to end everything-

It’s very hard to hear, and yeah, a person would need self-care just to make sure that you’re not being so depressed and so taken down by all those people, all those stories, so for sure.

David Bashevkin:

Rav Yoni Rossensweig, I’m so appreciative of you spending time. I hope we find out the title to your book. I hope it has another pun involved. I always end my interviews with more rapid-fire questions. My first question is I’m curious if aside from your own work, which now only exists in Hebrew. It will be coming out in English soon published by Koren. But I was wondering what other books do you have related to mental health that have opened up your eyes either about the intersection of mental health and religion and Halacha, or specifically mental health in general? What are the mental health books on your bookshelf that you would recommend to somebody trying to get a better understanding of this area?

Yoni Rosensweig:

So, I have a handbook of psychotherapy and halacha, I forget who wrote it. There’s a mental professional named Moshe Shapiro who wrote something back in the ’80s. If you want something less halachic and more just mental health, regarding trauma there’s a very famous book The Body Keeps the Score, which is worthwhile reading. I would say that’s good examples.

David Bashevkin:

I very much appreciated. My next question, if somebody gave you a great deal of money and allowed you to take a sabbatical with no responsibilities whatsoever to go back to school and study any area of your choice, what do you think the subject and title of that dissertation that you would produce from that sabbatical, what do you think the subject and title would be?

Yoni Rosensweig:

I actually once started a doctorate but never finished it. I started on Kant actually, and morality. So, I might go back to doing that, but today, my interest is more focused on psychology and psychiatry, so it could very well be it would be something in that area.

David Bashevkin:

My final question, I’m always curious about people’s sleep schedules. What time do you go to sleep at night and what time do you wake up in the morning?

Yoni Rosensweig:

I get up at about I’d say somewhere between 7:30 and 8:30 usually. I go to sleep quite late. I’m usually up until 2:00 in the morning at least.

David Bashevkin:

Rav Yoni Rosensweig, thank you so much for taking the time to speak today, and continued success and strength in your incredibly important work.

Yoni Rosensweig:

Thank you so much.

David Bashevkin:

I have a friend, I really know him mostly from Twitter, you can look him up. His name is Noah Marlowe, he’s a rabbi in Harvard. I think he’s part of the JLIC or the Harvard Hillel. I should really have that more clear. Find him on Twitter at @tzvei_dinim, it’s a very Yeshivish Twitter handle. Tzvei is spelt T-Z-V-E-I, space, Dinim, D-I-N-I-M.

Noah Marlowe’s great. He shares a lot of really fascinating stuff, and he shared something that I think is absolutely fantastic, which is the introduction to Rabbi Yoni Rosensweig’s book, which is called Nafshi Bishe’elati: Hilchot Briut Hanefesh, which was published by Maggid. And I believe is being translated into English. I don’t think that it has come out yet, I could be wrong.

I have the Hebrew version, and it is the laws of mental health. Really worthwhile, I have a copy. He co-wrote it with Dr. Shmuel Harris, and Noah Marlowe pointed out to me that there’s a really remarkable introduction that he actually translated, which we will have, of course, in our show notes in the introduction from somebody named Rav Re’em HaCohen. Who is a Rosh yeshiva in Yeshivat Otniel and one of the religious leaders in the Dati Leumi community. And he wrote an incredible introduction, and I wanted to share just a few words from it because, in the translation, he emphasizes how uncharted so much of this territory is.

And it opens up with, “The book before you deals with a topic mostly until now that has not been dealt with, the domain of psyche, mental health in halachic deliberation.” And he writes something I think incredibly important and remarkable where Rav Re’em Cohen cites the Gemara where Rav Shimon ben Menasya says that you can violate Shabbat in order that in the future you can observe more Shabbat in the future …

“Violate one Shabbos so you can keep many Shabboses.” And Rav Re’em Cohen translated by Noah Marlowe writes as follows on this, I thought it was very, very profound. “One of the foundational sources to create a host of halachic avenues to deal with mental illness based not only on immediate physical danger is the position of Rav Shimon ben Menasya on why one should violate Shabbos for life-threatening danger.” Rav Shimon Menasya said, “The Jewish people safeguarded the Shabbos. The Torah said violate one Shabbos so that you may keep many Shabboses.”

There are other rationale offered in the sugya about violating Shabbos to save a life, and the primary one is Shmuel’s position, “And you shall live by them, and you shall not die by them.” Deals with the immediate physical danger. But Rav Shimon ben Menasya weighs not only the value of life versus death but deliberates about a hierarchy of violating Shabbos temporarily for a full and proper life in the future.

While practically the position that we usually use, “And you shall live by them,” is the essentially halachic source, it’s valuable to relate to all the sources embedded in the sugya as worthy of independent value, and as well, the conclusions drawn from them. And what he talks about is the importance of understanding that even though mental health issues may diminish your current halachic observance, you may not be able to have that lechatchila observance, that idealistic observance.

But it is worth making those concessions, obviously, with the proper guidance, and stepping back and creating something that is more healthy and helpful in order so that one day you’re able to have a full and idealistic observance. And I think what that tells us is something really remarkable about weighing in your own future self and taking care of the present so that that future self will be able to emerge fully and completely.

And whether it involves leniencies or outright violations or whatever that may be, what is so important is that we have the confidence, number one, that our mental health issues are real. And there are real consequences to them in the halachic system. And number two is not only the confidence and the ability to admit to ourselves that our mental health issues are real. We are diminished and there are consequences to that diminishment.

But number two is having the faith, the emunah, the loyalty to the halachic system, and realizing that it can and does address us wherever we are. There is no stepping out and saying, “I’m too far gone, I’m too broken.” It is still addressing us even when it tells you to violate something. It is still addressing us even when it tells you to take a leniency.

And when you go ahead and try to seize onto an ideal when you don’t have the physical or emotional capacity to do that, then what’s guiding you is not halacha. It’s something else. It’s your own ego. It’s your own sense of I don’t want to make any concessions. I have my own image, my own self-image, whatever that may be.

If Halacha is truly guiding your life, it is guiding your life fully, and it accounts for our own diminishment and our own brokenness. It doesn’t mean that halacha never pushes us, it doesn’t mean that Halacha doesn’t make demands of us that can be difficult, that can be inconvenient. But halacha sees us fully in a healthy relationship with Halacha, a confident relationship with halacha. A relationship with Halacha that is imbued with emunah, with faith, is one that recognizes that it always needs to be addressing us fully. It shouldn’t come at the expense of our health, whether that is our physical health or our mental health. Of course, with the guidance of competent halachic authorities who know you fully, understand you fully, and understand halacha fully.

But one’s difficulty with mental health issues in the very present should not cloud a possible future where we can both step out of our own diminishment and be able to embrace halacha as fully as we are capable of. And that, of course, requires continued faith, not only in Halacha, but of course, in ourselves.

So, thank you so much for listening. This episode, like so many of our episodes, was edited by our dearest friend Denah Emerson, and thank you again so much to our series sponsors Andrew and Terri Herenstein. I’m so grateful for your friendship and support. If you enjoyed this episode or any of our episodes, please subscribe, rate, review, tell your friends about it.

You could also donate at 18forty.org/donate, and if you can’t donate, that’s fine too. There are so many other ways to help. Like our content, share our content, or use our episode sponsors twillory.com. Another reminder to log in, check them out, and use their coupon code. $18 off all orders of $139 or more for new customers only. Use the discount code 18Forty, and of course, you could also leave us a voicemail with feedback or questions that we may play in a future episode. That number’s 516-519-3308. Once again, that number is 516-519-3308.

If you’d like to learn more about this topic or some of the other great ones we’ve covered in the past, be sure to check out 18forty.org. That’s the number one eight, followed by the word forty, F-O-R-T-Y, dot org where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails. Thank you so much for listening and stay curious, my friends..

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Dovid Bashevkin: A Reform Rabbi Interviews an Orthodox Rabbi [Denominations 2/2]

David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko about denominations and Jewish Peoplehood.

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Frieda Vizel: How the World Misunderstands Hasidic Jewry

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Frieda Vizel—a formerly Satmar Jew who makes educational content about Hasidic life—about her work presenting Hasidic Williamsburg to the outside world, and vice-versa.

podcast

Diana Fersko: An Orthodox Rabbi Interviews a Reform Rabbi

We speak with Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue, about denominations and Jewish Peoplehood.

podcast

Shani Taragin: ‘It’s good that Judaism is hard’

Rabbanit Shani Taragin answers 18 questions on Jewish mysticism, including free will, prayer, and catharsis.

podcast

Bezalel Naor: Rav Kook’s Mystical Vision of Zionism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Bezalel Naor—author, translator, and expert on Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook—about Rav Kook’s relationship to the Land of Israel.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

Jonathan Dekel-Chen: My Son was a Hostage in Gaza for 43 Million Seconds. He Felt Every One.

Sagui Dekel-Chen was held hostage in Gaza for 498 days—or 43 million seconds. He came home on Feb. 18.

podcast

Leah Forster: Of Comedy and Community

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David sits down with Leah Forster, a world-famous ex-Hasidic comedian, to talk about how her journey has affected her comedy.

podcast

David Bashevkin: My Mental Health Journey

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin opens up about his mental health journey.

podcast

Moshe Gersht: ‘The world of mysticism begs for practicality’

Rabbi Moshe Gersht joins us to discuss free will, Mashiach, and consciousness.

podcast

Jonathan Rosenblum: ‘Would you want to live in a country run by Haredim?’

Talking about the “Haredi community” is a misnomer, Jonathan Rosenblum says, and simplifies its diversity of thought and perspectives.

podcast

Suri Weingot: ‘The fellow Jew is as close to God as you’ll get’

Suri Weingot joins us to discuss the closeness of redemption, godliness, and education.

podcast

Alon Shalev: How Rav Hutner Found Existential Meaning

Shalev, Author of Rabbi Yitzchak Hutner’s Theology of Meaning, talks existentialism, individualism, and more.

podcast

Rochi Ebner: Rav Kook’s Return to Our Soul

We speak with Rachel Tova Ebner about what the spirituality of Rav Kook adds to our Jewish practice and to our understanding of ourselves.

podcast

Kayla Haber-Goldstein: Questioning the Answers: Rebuilding Your Faith

On this episode of 18Forty, we have a frank conversation with author Kayla Haber-Goldstein about her personal, painful journey to find God.

podcast

Netta Barak-Corren: ‘I hope that Gaza will see a day when it is no longer ruled by Hamas’

Israel is facing several existential crises—at least three, by Netta Barak-Corren’s account.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Pawel Maciejko: Sabbateanism and the Roots of Secular Judaism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to historian and professor Pawel Maciejko about the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, Sabbateanism, and the roots of Jewish secularism.

podcast

Miriam Gisser: Recovery as Change

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Miriam about changing, or even rebuilding, one’s life.

podcast

Modi Rosenfeld: A Serious Conversation About Comedy

In this special Purim episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we bring you a recording from our live event with the comedian Modi, for our annual discussion on humor.

Recommended Articles

Essays

How Archaeology Rewrote the History of Tefillin

From verses in Parshat Bo to desert caves, tefillin emerge as one of Judaism’s earliest embodied practices.

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

How Rav Kook and the Lubavitcher Rebbe Saw the Jewish People

What if the deepest encounter with God is found not in texts, but in a people? Rav Kook and the Lubavitcher Rebbe…

Essays

5 Ways to Transmit Tradition to a Skeptical Generation

In Parshat Bo, the Torah anticipates skepticism—and builds tradition around the questions it knows will come.

Essays

A Letter to Children Estranged From Their Parents

Children cannot truly avoid the consequences of estrangement. Their parents’ shadow will always follow.

Essays

This Might Be What Saves Us from AI

In Klara and the Sun, Kazuo Ishiguro asks us to reconsider what, if anything, separates humans from machines.

Essays

The Siddur Has a Lot of Prayers. Where Did They Come From?

Between early prayer books, kabbalistic additions, and the printing press, the siddur we have today is filled with prayers from across history.

Essays

5 Ways a Heart Hardens: When Choice Becomes Destiny

In Parshat Vaera, Pharaoh becomes the Torah’s most unsettling case study in the limits of free will.

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

20 Books Our Guests Want You to Read

Moshe Benovitz, Susan Cain, Philip Goff, and other 18Forty guests recommended books. Here are the top 20.

Essays

The Hardal Community Explained: Torah, Am Yisrael, and Redemption

Religious Zionism is a spectrum—and I would place my Hardal community on the right of that spectrum.

Essays

How the Lubavitcher Rebbe Teaches Us to Transcend Ourselves

I consider the Rebbe to be my personal teacher, and I find this teaching particularly relevant for us now.

Essays

Is Judaism Fundamentally Zionist?

God promised the Land of Israel to the Jewish People, so why are some rabbis anti-Zionists?

Essays

Who Wrote the Siddur?

I’ve searched high and low for an accessible English book or essay addressing the development of the siddur, but my findings are…

Essays

Do You Have the Free Will to Read This?

The most important question in Jewish thought is whether we are truly “free” to decide anything.

Essays

How Did Modernity Change Jewish Prayer?

Modernity brought sweeping changes to the Jewish community—and prayer was not immune, not in Reform, Reconstructionist, Conservative, or even Orthodox communities.

Essays

How God Taught a Broken People to Hope Again

Parshat Vaera captures the moment when hope seems lost—and God answers with His Name.

Essays

Your Guide to Reading Rav Kook