Eli Rubin: How Do Mysticism and Social Action Intersect

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Eli Rubin – writer and researcher at chabad.org – to think about the stereotypes associated with social justice and vision, and how those seeming boundaries have been transcended.

Summary

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Eli Rubin – writer and researcher at chabad.org – to think about the stereotypes associated with social justice and vision, and how those seeming boundaries have been transcended.

Social reform requires that one embrace at least some change, leading some to think that it is antithetical to conservative worldviews. While the compatibility of Judaism and social justice movements is not guaranteed, it is often the case, even in some of what are seen as the more right-wing parts of modern Judaism. The modern history of social justice involves figures ranging from Rabbi AJ Heschel to the Lubavitcher Rebbe, and challenges some common assumptions.

- Has social justice been associated with mysticism and/or rationalism?

- What might social justice, or tikkun olam, mean within Judaism?

- What have various historical figures interpreted it to mean?

- What association does the Lubavitcher Rebbe have with social justice?

Tune in to hear Eli Rubin share his views on the historical relationship between social justice and the Torah.

References:

Social Vision: The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s Transformative Paradigm for the World by Philip Wexler, Michael Wexler, and Eli Rubin

To Heal the World? by Jonathan Neumann

Hasidism Beyond Modernity by Naftali Loewenthal

Transcript

David Bashevkin:

Hello and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast, where each month we explore a different topic, balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host, David Bashevkin, and this month we’re exploring social justice. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big, juicy, Jewish ideas. So be sure to check out 18forty.org. That’s 1-8 forty, F-O-R-T-Y, .org, where you can find videos, articles, and recommended readings.

I think when we talk about social justice, there are so many different frames with which we can think about this issue. And the primary frame that we have when this is discussed in the contemporary landscape, not in the Jewish community, but in broader society, is unquestionably the political landscape. The way that we bring change, the way that we enact any sort of social justice for the rest of society, is through the lens of political action. And the tricky thing about political action is that it relies on the societal fabrics that reciprocity, all of those feelings that we have and the way that we’re connected to other people in the society that we live.

But here’s the honest truth: a lot of times, that’s difficult, because I don’t know how well society, and when I say society I mean secular society in general, has done at creating that social cohesion that we so desperately need that binds people together that, ultimately, with social justice through a political framework, ends up boiling down to too often, and I’m being descriptive, not prescriptive here, but very often it boils down to this form of reciprocity of, “Well, what have you done for me lately?” And each community feels a grieve. So when another community comes to a different community and says, “Why don’t you stand with me?” Very often, our political divisiveness comes to the front if the only lens that we really have is our political cohesion. If that’s the frame we use to understand the imperative for social justice, then sometimes we rise to the occasion, but sadly, more often, we kind of fall to the lowest common denominator and that is the political divisions that continue to exist in any normal functioning society. That’s the nature of how politics work. Which is why I am so excited for our next guest, Rabbi Eli Rubin.

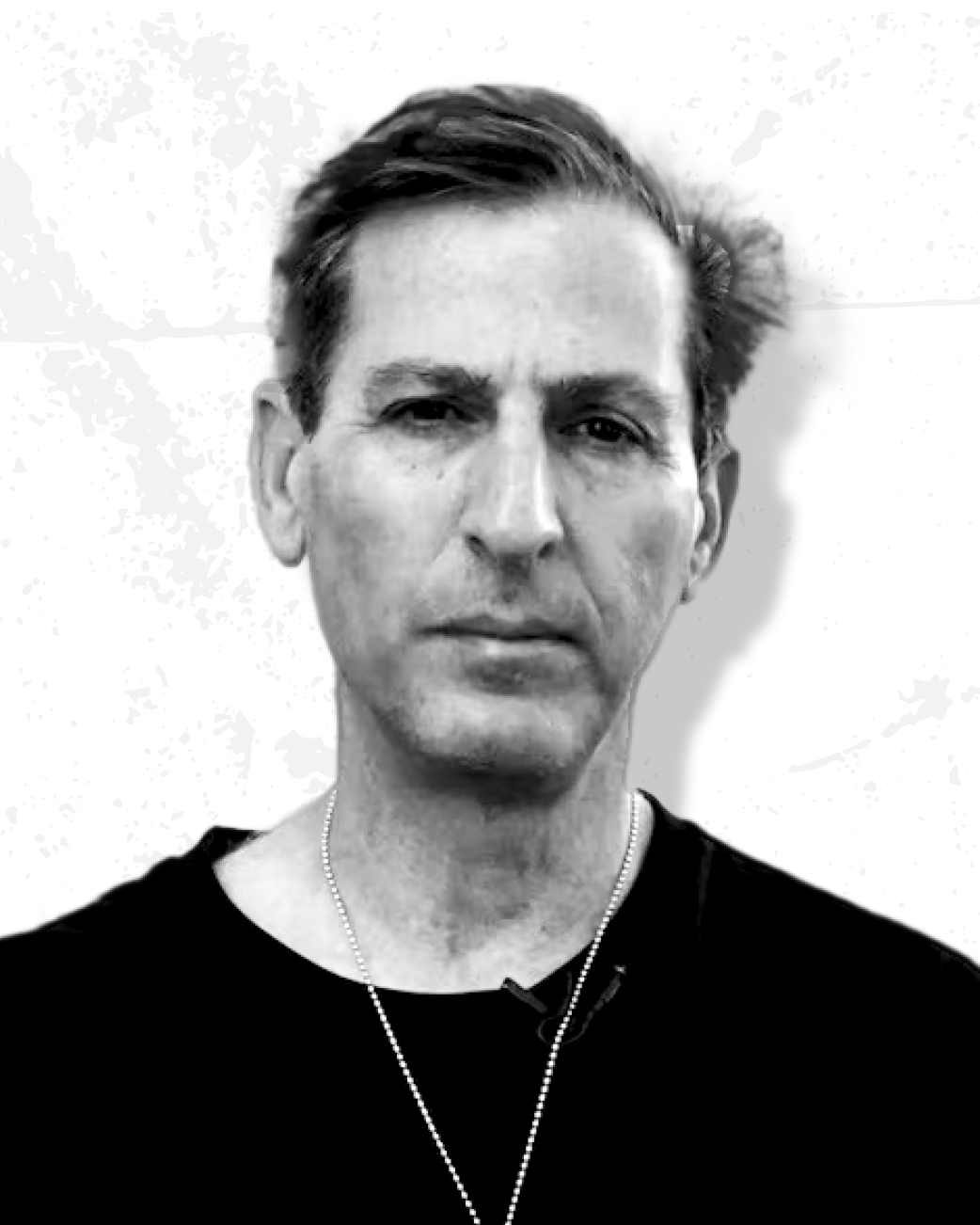

Rabbi Eli Rubin wrote an absolutely outstanding book that challenges what is the frame we can use when we think about the responsibility that we have for others inside our community, outside of the Jewish community, and throughout the world. And he suggests that maybe that frame is not political philosophy, but maybe it is mystical theology. It is mystical ideas that we can use as the imperative, as the groundwork for our responsibility to others. And Eli, aside from being an incredible scholar and a dear friend of mine, I know him on Twitter where you could absolutely check him out. His handle on Twitter, for those in that space, is @Eli_Rubin. It’s so kind and generous of him to come onto here. He is a scholar for Chabad.org. He’s written in both academic and traditional circles. And his ideas and the clarity with which he comes about them are simply remarkable.

The name of his book, which we talk a great deal about, is called Social Vision, which he wrote in partnership with Philip and Michael Wexler. And it’s an absolutely outstanding book, which really articulates the philosophy of the Lubavitcher Rebbe as it relates vis-a-vis social action. And the most fascinating part of this book is the genesis of the book itself. Before you’re like, “Okay, we know, classic Chabad guy put up the Rebbe as the paradigm for all this,” but he’s not the person behind the book. It was Philip Wexler, a sociologist and scholar in Israel, who really came to him with this idea for the book because he was struggling for, how do we ground this sense of responsibility? Because the other frameworks, whether it’s sociological frameworks or political frameworks, too often are falling short. So without further ado, I am so excited to introduce my friend, Rabbi Eli Rubin.

Hello and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast. It is my absolute pleasure to sit with a friend, my dear friend, Rabbi Eli Rubin. Rabbi Eli Rubin wrote a phenomenal book, which we’re going to talk a great deal more in-depth, called Social Vision with Philip and Michael Wexler, which talks about the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s transformative paradigm for the world. He also works a great deal with Chabad.org and so many of the educational programming of Chabad. Rabbi Eli Rubin, it is an absolute pleasure to be sitting with you today.

Eli Rubin:

It’s a pleasure to be here with you too. Thank you.

David Bashevkin:

So where do we start in this conversation? I think the hardest thing when it comes to talking about social justice, social action, tikkun olam, there are so many terms that are all mixed up with each other. So maybe it makes the most sense to begin by defining our terms. When someone were to ask you in the world, and we’re going to spend a great deal of time talking about the Rebbe. And we should make a disclaimer from the outset that, when we talk about the Rebbe, at least in this conversation, not in all of my conversations, but in my conversations with you –

Eli Rubin:

Of course.

David Bashevkin:

The Rebbe that we are referring to is the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson. When we talk about social action, social justice in the thought of Chabad Chassidus, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, what do those terms mean?

Eli Rubin:

It’s a really great question because so often we use terms that come in from the outside world, and we adopt the definitions that are given to us by the culture that we find ourselves in. And the Rebbe was actually very conscious of this and worked specifically and explicitly to articulate what he meant and to place his ideas as a counterpoint, in many ways, to the prevailing ideas, to the prevailing culture.

So one example of this, which I was thinking about, is from a talk that he delivered in 1952, which is very early on during his leadership. When he started to talk about the idea of teshuvah, return or repentance, tefillah, which is usually translated as prayer, and then tzedakah, which is usually translated as charity. And in his talk, which was a talk delivered in Yiddish, he analyzed these terms and analyzed the way they’re translated into English and said that the English translations actually do not do justice to the concepts. So I’m just going to focus in on tzedakah, because usually it’s translated as charity, but the rabbi insisted that it should be translated as gerechteit, rightness or justice.

So there we have, as opposed to, and he articulates the idea why. What’s the difference between charity and justice? And I think this helps us to get an understanding, more generally, of when we talk about social justice, what would we mean applying that concept to the Rebbe or talking about the Rebbe’s concept of social justice? His analysis of tzedakah is that, whereas charity is a kind of hierarchical concept where a person is giving because he’s kind, not because there’s any obligation, and so the poor person is poor and the wealthy person is wealthy. And out of the goodness of the wealthy man’s heart, he gives charity. In Judaism, it’s not a question of kindness, it’s a question of what is right, what is just. In other words, there’s an obligation. And that obligation, importantly, doesn’t come just from the bond between individuals, between the social bond, as it were, or the horizontal bond between people in a society, but it comes from God: Because God has given me that money and given it to me in trust, therefore, I’m obligated to use it in the way that God intends for me to use it.

So there, already, you have a concept of justice. And this justice isn’t just social justice, but in the book we actually use the term socio-mystical justice, because we wanted to emphasize that there’s this other dimension, which is at the core of the Rebbe’s thinking about justice and about society. There’s another dimension, which we call the vertical dimension, which is the relationship between the individual, the society, and God. So that third dimension, the divine dimension, is crucial to everything that the Rebbe is talking about. And whenever we talk about the Rebbe’s projects and the Rebbe’s concern for others, what’s driving that is always the divine. It’s a religious enterprise, not a secular one. And I think that’s also key to the argument of the book, and it needs to be emphasized.

David Bashevkin:

Well, we’re going to get to the book.

Eli Rubin:

Sure.

David Bashevkin:

I want to unpack that a great deal more. Before we get to the book, what I want to ask you is, I almost want to start with the inverse a little bit, and talk a little bit about the critiques and the discomfort that people have. I’ve mentioned, with a lot of people on this subject, that there’s this book by Jonathan Neumann called To Heal the World, which levies a fairly, it’s pretty vicious, a vociferous critique on the notion of tikkun olam. This book is called To Heal the World, but it’s followed by a question mark. And his basic premise of the book is that the notion of tikkun olam has been co-opted by the political left-wing to justify everything and become their whole Judaism. And that’s the only thing that they emphasize. And I know other people, I had a great friend named Joel Alperson, who lived in Omaha, Nebraska, who actually flew me out there for a wild Yom Kippur. I could share a different story. I spent Yom Kippur at the opening of the Big Red football game for a different –

Eli Rubin:

That sounds like a Chabad story.

David Bashevkin:

Exactly. I shared it with you now. It’s the closest I ever got to being an actual Chabad Shliach, was spending Yom Kippur at the opening day of a college football game. FYI, it was absolutely terrifying because the team is called Big Red, so when you step out, the whole city was, there were red balloons and red tapestry everywhere. And again, the imagery of red on Yom Kippur is –

Eli Rubin:

Right, right, right. Oh, wow.

David Bashevkin:

It’s not all that auspicious. So I was pretty convinced that this was going to be my last Yom Kippur.

Eli Rubin:

Were you able to work a miracle where all the red turned to white?

David Bashevkin:

No, it did not go that planned. The fact that I survived, I think, was the miracle. But my friend, Joel Alperson, did write an article with a similar critique that the notion of tikkun olam has replaced what Judaism is all about. Judaism becomes whatever’s in vogue, whatever’s woke, whatever is great on left-wing politics, whatever their pet project is. And my question is, how do you think the Rebbe would have responded to these critiques of the notion of tikkun olam? Would the Rebbe have agreed with these critiques? Would he have found maybe a different path in there? How does a Chabad chassid, who in some ways embodies so much of this tikkun olam mentality, but in other ways really doesn’t, what do you think is the response to this critique on the intermingling of left-wing politics and that commitment to really heal the world?

Eli Rubin:

The first thing I would say is I would object to this idea of intermingling because I don’t think the Rebbe saw it as left or right. I think the Rebbe suddenly transcended that kind of binary and wanted people to transcend that binary. He didn’t want people to feel that they needed to be shoved into a box and you can only be religious if you’re to the right politically, and if you’re to the left, then you have no place in the religious world. So that’s number one, but more broadly, there’s a story which comes to mind. There was a Rabbi Krupnick, who was in the Yeshiva RJJ back in the 1960s, and now I think he lives –

David Bashevkin:

We love RJJ. My brother-in-law is a shoel umayshiv in RJJ. That’s the person who answers the questions that the young students have. So we’re big RJJ fans. So this Rabbi Krupnick at RJJ, before I cut you off –

Eli Rubin:

So he came into contact with Chabad. This is in the 1960s, when RJJ was in Manhattan, I think lower Manhattan near Greenwich Village, which was a big, that was one of the epicenters of the counter-cultural hippie movement, the Beatnik Movement. And he came into contact with Chabad. I think that Chabad students were coming to RJJ and studying Tanya in an informal way and making some inroads there. And his Chabad friends wanted him to grow a beard. Now, part of the problem with growing a beard in those days wasn’t just that it would be seen as taking a position that was too big for one’s position. A rabbi wears a beard. A student, a Yeshiva bachur, doesn’t have the standing to wear a beard, but in those days, there was another problem, which was that the hippies wore beards. So it was actually seen as bohemian, and not necessarily a label or a mark of Jewish identity, but a mark of identifying with what a lot of Jews, especially religious Jews, would see as a lifestyle that was not very religious at all.

David Bashevkin:

The Woodstock crowd.

Eli Rubin:

The Woodstock crowd, exactly. So he decided that he’s going to ask the Rebbe, himself, whether he should grow a beard. And he was pretty sure that the Rebbe would say, “No, don’t bother growing a beard. This is not an important thing,” and that’s because the Rebbe had this image of being a young, modern Rebbe, a cosmopolitan Rebbe. And the Rebbe, himself, because he had that image, people often were surprised when the Rebbe actually turned the tables on them. And in this case, actually, I think what’s really interesting is that the Rebbe, on the one hand, the Rebbe made the argument to him that the hippies were actually, in some way, embracing Jewish marks of identity. Even though that was not necessarily what they had in mind, but the fact was they were wearing different clothing, they were wearing beards, they all have Jewish names, the Rebbe pointed out to him. The Rebbe actually listed them, a bunch of names of leaders of the Beatnik Movement and said, “These are all Jewish names. They’re not changing their names. They’re embracing their names.”

So the Rebbe lifted this up and said, “This is,” embraced it in a certain way as being a mark of Jewish identity, but at the same time, the Rebbe was using that for what we would see as a conservative agenda, right? To uphold a conservative agenda, which is grow your beard because it’s a religious value. So that’s an interesting story, which shows how the Rebbe was burning both ends of the candle, in a way. Now, more conceptually, I think that it’s important to say that the Rebbe has a concept, and Judaism, actually, has this concept of, we have 613 mitzvos. We have a big Torah and it’s an integral hall. So anyone who picks up one element of the Torah and says, “This is what I think is important and the other part is not,” whatever their reason, is making a mistake, right? But again, another part of this is that the integrity of the Torah has another facet. And that is that ha’osek bamitzvah patur min hamitzvah. If you’re doing one mitzvah, then you are absolved from your obligation to do another mitzvah.

And in the Zohar, there’s a really interesting story about this, which the Rebbe discussed, actually, in a Simchas Torah talk, I think in 1958, which is also exactly the spirit of the counter-cultural movement. And the Rebbe wasn’t connecting it to that at all, but I think it bears on this because what the Rebbe said was, the story in the Zohar is that there was a yenukah, a young child, who was able to perceive spiritual states. And two rabbis came and visited his mother and he said, “I can smell that you haven’t read the Shema today.” And the rabbi said, “You’re right. We didn’t say the Shema today, but that’s because we are working on the mitzvah of hachnasat kallah, we are raising money for a bride,” which is a charitable philanthropic endeavor. It’s a social endeavor, right? This is social justice in the Zohar. The rabbis skipped the reading of the Shema in order to raise money to help a destitute girl marry in a proper way.

So the Rebbe discussed how, on the one hand, this shows that they were absolved from the mitzvah because they were doing the different mitzvah. On the other hand, the fact that the child, the yenukah in the Zohar, was able to sense that they had not fulfilled the mitzvah meant that this shows there’s still something missing. So to get back to your original question about social justice versus, if it’s replacing Judaism, then obviously that’s a problem, but at the same time, we have to realize that it is an integral part of Judaism, and if you’re trying to cut that out of Judaism, it’s also a problem.

David Bashevkin:

I very much appreciate that. I guess maybe where we should start speaking about is not in the response to the criticism, but the proactive vision that the Rebbe articulated. And maybe you could tell me a little bit. As far as I know, you haven’t written a great deal of books, but you were a co-author on this book called Social Vision: The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s Transformative Paradigm for the World, by Philip Wexler with Eli Rubin and Michael Wexler. How did you get involved in this book? Who is Philip Wexler? And what was the impetus to write? There’s so many aspects of what the Rebbe has contributed to the world, and this is by a secular publisher. This is not by Kehos or an in-house –

Eli Rubin:

Absolutely.

David Bashevkin:

Chabad publisher. So how did this come about?

Eli Rubin:

So you’re right. This was not a book that I set out to write, myself. This is a book that I was co-opted to by Philip. Philip is a really fascinating person. He’s a sociologist, classically-trained sociologist. He started out, many years before I was even born, studying education, schools and how schools help shape identity. But as time went on, and by this time he was, in the late 1980s, he was the head of the School of Education at the University of Rochester, and it was then that he started to study Hasidic teachings. He became acquainted with the Chabad shliach on campus there, but also intellectually and in his own work, in his own scientific, sociological work, he really felt that he was coming to a dead end and that social theory was coming to a dead end. So he started to look to religion for new social ideas. And this is building on the original founding figures of sociology, Max Weber and Emile Durkheim, who understood –

David Bashevkin:

I need to interrupt you because, any time I hear someone properly pronounce a last name that I’ve been mispronouncing for most of my life, I’ve always been calling it Max Weber.

Eli Rubin:

Right. That’s what I thought until I met Philip.

David Bashevkin:

It’s Weber. So tell me, what were the questions that he was interested in that brought him to Hasidic thought? You were talking about Max Weber.

Eli Rubin:

Weber had this idea that mystical movements cannot ever really produce community. They can’t create new forms of social life because mysticism, he had this phrase, mysticism always comes down to the acosmism of love, which means the denial of, the love of God denies reality to the physical world and to people. And so mysticism is a kind of escapism. He called it other-worldly mysticism. But there’s another, he did agree, though, he did suggest –

David Bashevkin:

This is Weber’s critique.

Eli Rubin:

This is Weber’s analysis.

David Bashevkin:

And Weber lived in the early 1900s.

Eli Rubin:

Yes.

David Bashevkin:

Correct?

Eli Rubin:

Yes.

David Bashevkin:

And he’s critiquing religion and basically saying that this mystical inclination is the opposite of forming any sort of social cohesion because you’re going to end up living up in the mountains –

Eli Rubin:

Exactly.

David Bashevkin:

-and meditate.

Eli Rubin:

So he didn’t criticize religion, per se. He felt there were different religious models, and he actually argued that the, what he called inner-worldly asceticism, which he saw as Protestantism, was inner-worldly asceticism, actually did shape society. And he argued that western society capitalism came out of that particular religious tradition and its secularization.

David Bashevkin:

The protestant work ethic that was –

Eli Rubin:

Exactly, the protestant ethic became the spirit of capitalism. But what Philip picked up on was that there was another category, which Weber mentioned, but never analyzed, and that is inner-worldly mysticism. In other words, there’s other-worldly mysticism, but there’s also inner-worldly mysticism. You could have a mysticism in the world, but that had been left unexplored. And Philip thought that, actually, Hasidism provided an example of inner-worldly mysticism. It’s a mystical movement with a very well-developed intellectual system of thought, but it has also become a social movement, and a very successful one at that. It’s the most dynamic social movement in modern Judaism.

So Philip decided that he’s going to pursue a new course in his own scientific work. And he went to Jerusalem, to the Shalom Hartman Center, and took a fellowship there for two years. He took a sabbatical from the University of Rochester. This was in the early 2000s, but he never went back. Instead, he took a job at Hebrew University, and he was the head of scholar education there, but he became friends with Moshe Idel and with Jonathan Garb and he convened a yearlong study group at the Institute of Advanced Study in Jerusalem to study society and mysticism. And he brought people from America and it was an international group.

But that was what got this ball rolling, and he started exploring how the concepts within Jewish mystical thought and within Hasidism actually are social concepts. And this was groundbreaking in the scholarly world of the study of Jewish mysticism because, although a lot of work has been done, and I think it’s common wisdom, that Hasidism took Kabbalah and made it psychological, what he was arguing was there’s another whole side to Hasidism, which is its social dimension. And it’s not just the way Hasidim live in the communities, but the ideas are social ideas. And this book came out of that. I was introduced to Philip in 2012 and we got talking, and talking, and talking. And then, eventually, we used to joke, “We’re going to write a book one day called Weber and the Hasidim,” but then it became Social Vision.

David Bashevkin:

So I’m so fascinated by this concept that I wanted you maybe to speak about it a little more because I think, I didn’t grow up in the Hasidic community. I knew Chassidim. My father had patients who were Chassidim. And I think, when you grow up in America, the concept of mysticism, I think we all have that influence from Weber about mysticism taking you away from the world, taking you out of the world, mysticism negating the world and all those things. What do you think is unique about the Rebbe’s contribution in how this mystical perspective actually animates and embraces the world more? Where was the Rebbe coming from that he developed this vision? Any different maybe than previous Hasidic leaders? What was the Rebbe’s contribution to this?

Eli Rubin:

In a way, yes, and in a way, no. So there’s suddenly a great deal of continuity, but there are certain things which are very different. So let me say something first about the continuity and then I’ll say something about what’s different. So if we go back, since we’re talking in the Chabad context, if we go back to the founder of Chabad, Rebbe Shneur Zalman of Liadi, there’s actually a whole section of Tanya, the third section – Is it the third section? – the fourth section, Iggeres Hakodesh, which are fundraising letters. Now, if you read those letters, what’s going on there is –

David Bashevkin:

Wait, pause for one second. There were fundraising letters?

Eli Rubin:

Fundraising letters, yes. So let me explain. In 1877, a large group of Hasidim traveled to the land of Israel. So now, the Hasidic community of Russia, of [inaudible], as it’s called, was split between communities in the Holy Land and communities back home in Ryssen. And the idea was that the communities back home would send money to support the Torah study and the prayer and the worship of the Chassidim in the Holy Land. And so, every year, the Alter Rebbe, Rebbe Shneur Zalman of Liadi, was the head of Kollel Chabad, of the Chabad fund, to support Chassidim in the Holy Land, but he endowed this with very much a mystical or a socio-mystical theoretical foundation, that our life in this world, and our physical life, our life as people working, doing business, making money, supporting our families, is dependent, is interlinked, with a spiritual work that is being done by our fellow Chassidim across the ocean in the land of Israel.

So already there, you see that this kind of socio-mystical network by which there’s this kind of mutual support going on, their spiritual work helped us and our physical work helps them. That was kind of in the bones of Chabad from the beginning. And sometimes, even though everyone studies Tanya today, that part of Tanya gets left behind to some degree or people aren’t, even if they do study it, they’re not really aware of the historical context or what’s really going on. It’s just, “There’s a lot of stuff about charity for some reason in the back of the Tanya,” but this was really a fundamental part of life for Hasidim at that time, at the end of the 18th century, beginning of the 19th century. Coming down –

David Bashevkin:

He was weaving a social cohesion between the Hasidim who were still in Russia and those who had already moved into –

Eli Rubin:

Exactly.

David Bashevkin:

Eretz Yisrael, into the Holy Land.

Eli Rubin:

And he said you can’t have real love and fear of God, you can’t experience compassion for your soul which is descending into the body, if that compassion is not exhibited and practiced in real compassion, giving money. So there’s this interlink. In a sense, what you do with your money proves that what you feel in your soul is actually real. So that’s actually an argument that he makes in some of these letters. So this is really fundamental to what it is to be a Chabad Hasid back in those times.

Now, coming down to the modern context, the Rebbe is now in America and is not just about the community of Hasidim. I think this is where the big difference is, and the Rebbe, himself, acknowledged this and spoke about this, that the Rebbe felt that in America, in the American context where you have freedom of religion and freedom of speech, we have the ability to share Judea’s message and the spiritual message of Judaism with the world, with non-Jews as well. And so that’s where you start to see that the Rebbe really begins to think about policy issues that aren’t just relevant for Jews. And he’s not just thinking about what his community needs and he’s not just thinking about the survival of his community and the preservation of the past, but he actually sees a new opportunity for the growth, for the expansion of the Hasidic ethos. And this is a big part of Philip’s concept, also, that the Hasidic ethos can become a blueprint for larger social change and for new models of how society creates value or determines what is valuable and determines policy. So I don’t know if you want to talk about some of those –

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, we’re going to get back to the question of non-Jews in a second. What I was hoping that you could talk about is, there are these very lofty ideas, particularly in Chabad Chassidus, about the soul and these very mystical ideas of how we interpret the Torah and approach Jewish life and commitment. And then you have to step out and look at your average Jew and your average non-Jew, regardless. How did the Rebbe articulate that responsibility? How did he bridge that gap between the loftiness of the ideas that he shared at the farbrengen, at the large gatherings of the insiders, and ensure that it translated to outsiders? What did the Rebbe do to ensure that the topics of conversation that he discussed actually translated into the way that his Hasidim felt a responsibility to others?

Eli Rubin:

That’s a really good question. I think there’s a couple of answers to that. Number one, the very first talk that the Rebbe gave when he accepted the leadership in 1951, when he officially accepted the leadership, he said, “If you want to hear a mission statement,” and you can actually hear, you can listen to the tape. This was recorded. And he says the words, “mission statement,” in English. He’s talking Yiddish, but he says, “statement.” He says, “The mission statement is that there are three loves; love of God, love of the Torah, and love of the Jewish people. And these three are one.” And then he says a more radical statement, which is that, “You could have love of God and it’s not real because you don’t have love of your fellow Jew. And you can have love of the Torah and it’s not real because you don’t have love of your fellow Jew. But if you have love of your fellow Jew, that will bring you to love of the Torah and to love of God.” So he from the outset set this, the social dimension, as the preeminent measure of what it is to be an engaged Jew, to be a spiritual Jew. You can’t be a spiritual Jew if you haven’t first created that horizontal bond with other people, with other Jews. Now, there –

David Bashevkin:

Of those three things, that’s such a remarkable statement; of one’s love for the Jewish people, that social component, love of God, the theological component, and love of Torah, that religious commitment component. The Rebbe said the one that includes and will lead to the other two is start with the people.

Eli Rubin:

Exactly.

David Bashevkin:

And the Rebbe said, and he uses that almost like, that was the mission statement of seeing –

Eli Rubin:

That was the mission statement. So I think, from the get-go, people understood that this was not going to be an other-worldly mysticism. This is going to be an inner-worldly mysticism. This is going to be a mysticism that is going to permeate, that is going spread outwards. Again, this goes back to the beginning of Hasidism. The founding letter, in a sense, the founding text of Hasidism is the Bal Shem Tov’s letter to his brother-in-law, Reb Gershon Kitov, where he says that the Messiah will come when the world can spread to the outside. And America was the outside, and it was seen as the ultimate opportunity. And the Rebbe in those years, in the 1950s to 1960s, spoke about America as a source of cultural influence on a global scale, an export of political influence, of economic influence, of cultural influence. And the Rebbe wanted to tap into that and use that model, ride that wave, as it were, and export divinity, spirituality, godliness to the whole world from America. So people understood that from the beginning, but there are other ways also. Technology, right? From the beginning, the Rebbe was –

David Bashevkin:

I know. I visited 770 once and I was shocked when I saw the dial-up of the radios, of all the plugins of how people would broadcast outwards. And I think I maybe even mentioned to you once how one of the most fascinating things is, when you go into the library in 770, there are woodcuts from the original artwork of Alice in Wonderland. I got a big kick out of that. That predates the Rebbe.

Eli Rubin:

Yeah, yeah. Absolutely.

David Bashevkin:

From his father-in-law. But let me ask you this. And I want to get to that next question about the non-Jewish world, and specifically Chabad vis-a-vis the responsibility to the non-Jewish world, but before I get to that, I wanted to talk about this social manifestation of seeing a religious affinity and a godliness in other people. I think something that any teacher or anybody in any position of power, and dare I say specifically religious power, it’s very easy for, whether it’s Chabad or an outreach rabbi or a campus rabbi or your local rabbi in your neighborhood, to look at others, and they become like your esrog. They become objectified. They become people who you shake like a lulav. And you look at them as an other. And my question is, how does Chabad avoid that stereotype, which we all succumb to in one way or another, that the responsibility of outreach, the responsibility of connecting to Jews, it doesn’t just become, “Oh, they’re devoid of holiness, and it’s my job, as the hero, Messiah complex, to come in and save the whole world?” That’s not the impression I get. And my question is, how did the movement not become that, where you look at people as objects and the other as vehicles to your fulfillment?

Eli Rubin:

I think that, ultimately, that goes back to the depth of the teachings that underpin all of this. And that is, number one, if you go back to the Tanya, in chapter 32, which is a very famous chapter, you have the idea that when a person becomes aware of their soul and retreats, as it were, into their essence, they actually become cognizant of the fact that, in their essence, they are one with other people. So again, this is the very opposite idea of the acosmism of love, which says once you have a mystical experience, nobody else exists. On the contrary, when you have a mystical experience, you become aware that you are one with everybody else. That idea, itself, is saying that it’s not that I am one individual and you are another individual. On the contrary, we are intertwined. In our source, we are intertwined. We are one. We are encompassed in the one God.

So if you are not complete, I am not complete. And the fact that there are different people is because different people have different functions and can all gain from one another. One of the big ideas that we discussed in Social Vision is the idea of reciprocity, that happiness, that completeness, comes not through hierarchical relationships where a person is just giving or a person is just receiving. There’s no satisfaction in that. If a person is only giving and not receiving something back, then again, it’s just kind of empty power play, as it were. And if a person is just receiving, then they don’t feel good about themselves either. Okay. They have what to live on, they’re sustained, but there isn’t any satisfaction.

Satisfaction comes when two people realize that each one has something they can offer, something they can learn from one another, something they can gain from one another, and they create a partnership which has a equal basis. It’s not always equal in every way. If it was equal in every way, then you wouldn’t need each other. If it was a complete equality, this is another controversial dimension, the Rebbe’s thought on this, is that the Rebbe is not so interested in complete equality where everyone has the same things. The Rebbe’s interested in a different kind of equality, which is a reciprocal equality where people have things of value.

David Bashevkin:

Everyone has something to contribute.

Eli Rubin:

Everyone has something different to contribute and to gain from somebody else. And that’s what equates a need for you to come to somebody else, give them something, and receive something in return. And that’s where joy is created. When you see that you are able to fill someone’s lack, that actually fills your lack. And when they fill your lack, you fill their lack. Another dimension of this goes back to the talk of the Rebbe about a famous story in the Talmud about Reb Elazar, the son of Reb Shimon bar Yochai, who was the hero of the Zohar. And so he’s the ultimate figure of pedigree scholarship, Reb Elazar. His father is the great Reb Shimon bar Yochai. And he is traveling home, I think from his teacher’s house, on a donkey, and he sees what the Talmud calls an adam mechor, an ugly person. And he remarks on this, “How can you be so ugly?”

David Bashevkin:

I want you to know, let me jump in, this happens to be, without a doubt, my favorite, but I find this passage so deeply moving. I’ll let you finish the story, but when I was a teenager and my hair started going gray, I was 16, 17 years old, people used to walk up to me and be like, “What’s the story with you?” I literally felt like a figure in this passage because people used to walk up to me and literally say, “You’re so ugly. What’s the story with you? Why is that – ” I mean, they wouldn’t call me ugly, but they would say it in nicer terms.

Eli Rubin:

There’s this otherness. There’s this feeling of being other.

David Bashevkin:

Yes. There was this otherness of, “Are you stressed out? Are you depressed? Are you frustrated?” In my heart of hearts, I’d be like, “Now I am, all of the above, now that you’re coming up to me as a carefree 16 year old,” but this idea of a rabbi walking up to somebody and saying, “Wow, you’re so ugly,” it always resonated with me, but finish the story and tell me what the Rebbe took from this.

Eli Rubin:

I mean, the story in the Talmud itself is powerful enough. In a way, you don’t need more than that, but the Rebbe also has a commentary.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah.

Eli Rubin:

So in the Talmud, what happens is that the ugly man says, “lech leha’uman asher asani. Go to the craftsman who created me,” i.e, God. And the Rebbe links this to the passage in Pirkei Avos which says that, “Mikal melamdo hiskalti ki edasecha sicha li. A person has to learn from everyone, because your testimony speaks to me.” Everything is a testimony to God. “Go to the craftsman who created me.” Everything is an exhibition of God’s craftsmanship. And anything you encounter has to be seen, in that way, has to be seen as a divine testimony, as God talking to you, as God communicating something to you. Which means, in other words, it’s like Torah. To encounter somebody is like sitting in front of a Torah text where God is, it’s divine wisdom.

David Bashevkin:

And in fact, the conclusion of that very passage is that, the end of the story is that the flexibility that both this ugly person and Reb Elazar in learning how to reconcile with each other is the very reason why we write a Torah and a mezuzah, these objects of holiness that we learn from, with a specific type of pen, with a kana, with a reed, which I’ve always found so moving. When the Rebbe’s basically saying, you need to approach people with that sense of interpretation and love that you can derive something from everybody, even if at first glance they look ugly.

Eli Rubin:

That person is a teacher. You can never come to somebody from a hierarchical position of, “I am someone who has the knowledge and I am here to teach.” As soon as you do that, you’re no longer a teacher. And not only that, you’re no longer a learner. So, “[inaudble],” you learn more from your students. You can only learn more from your students if you’re willing to put yourself in the position of being a student, relative to your students, and seeing them as a teacher in some way. So that’s a demand for openness in a very radical way, and in a way that you would not necessarily think of as being a Torah value, to be open in that way. Oftentimes, we think, “No, we have the Torah. We lay down the law,” but there’s something here about actually being open to seeing things, with things that you encounter in the world have to be weighed seriously and seen, in a sense, as Torah. And that’s a difficult thing to navigate.

David Bashevkin:

That’s something that you can learn from. It is absolutely my favorite passage. And for me, it was something very real that I felt like I lived through, but to re-couch it as the obligation to look at society, I find so deeply moving. I want to shift, and this is the last major topic that I wanted to discuss, and maybe this is the boundaries of who you can learn from and who you can connect with, but there seems to me to be some sort of, I don’t want to call it a paradox or tension. There is an emphasis throughout Judaism, particularly in Chassidus, about the uniqueness and importance of the Jewish soul, the Jewish person, the Jewish community. Yet we find, specifically with Chabad, maybe more so than any other Hasidic movement or Jewish movement that I can think of, a deep, deep sense of responsibility to engage, interact, affect, move, inspire the non-Jewish world.

So I’m wondering if you can help me understand, why did the Rebbe spend so much time in programming and in educational missions in the non-Jewish world? Why not focus on him, focus on the Jews? We’ve got stuff to work on. Where did that sense of responsibility derive from, and how was it manifest?

Eli Rubin:

Well, I think that this really goes all the way back to the beginning, if we think about Avraham Avinu, our forefather, Abraham. God says, we read that, “Avraham is blessed by God. Haya yihye l’goy gadol b’atzum, v’nivrichu [inaudible] kol goyei ha’aretz.” That Avraham will be a great nation and all the nations of the world will be blessed through him.” So the idea of choseness, that the Jews have something special, for the Rebbe was always about responsibility, that the Jews are chosen not to be an end to themselves, they’re chosen to bear, to carry a message and share it with the world. And if we look at the next verse, where you have a sense of what the message should be, “uvishamru lederech Hashem la’asos tzedakah umishpat,” they will guard, the descendants of the legacy of Abraham is that his descendants will, God will preserve the path of God to do justice.

So the Rebbe suddenly saw this as integral to Judaism, that Judaism is not just the Jews, that Judaism has a universal message and wants to heal the entire world, wants to create a just society for the world. And the Rebbe pointed to Maimonides’ Code, the only comprehensive Jewish code, the Shulchan Aruch, is a legal code that governs most of what we do nowadays, but doesn’t govern the era of the temple. It doesn’t govern the Messianic Era, whereas Maimonides’ Code is a comprehensive code of law. And there, Maimonides details the obligation of Jewish people to share an ethos, a religious ethos, a moral ethos with the world, the seven Noahide Laws. And the Rebbe spoke about this extensively, but the key is that beyond the specifics of the laws, it’s that the underlying concept is an awareness of an obligation to God. So many of the laws, the Noahide Laws, you could just see as kind of universal values that you find out they’re in the secular world, justice, create courts, create law, care for the destitute, whatever. Don’t cause pain to animals, don’t steal. These are generic things, but part of the underlying idea here is, or the main idea here for the Rebbe, is that this needs to be inspired by, like we said before, the vertical dimension, that there’s a divine, this isn’t just about making sure everyone gets along down here. This is coming from a deeper place, that the imperative that lies behind justice is divine. And it’s not just about a human arrangement. We shouldn’t just be thinking about it in secular terms or utilitarian terms. There’s an absoluteness to this value, which is given, endowed by God.

David Bashevkin:

Tell me a little bit more, because I’ve always been so fascinated in the areas where the Rebbe had these educational missions to the non-Jewish world. I mean, the Rebbe certainly emphasized these, the seven Noahide Laws. Where else was the Rebbe emphasizing to the broader world to bring these values out?

Eli Rubin:

So the main two policy areas where the Rebbe was especially vocal, to the point of even talking about the current political situation and what the president was doing, what congress was doing, and talking about really getting into the nuts and bolts of current political debates in his time, was with education, public education, which again, you wouldn’t think that a Hasidic rebbe would be a big fan of public education. Hasidim don’t send kids to the public schools. They have their own private institutions. And actually, many people are weary of, especially religious people, are weary that, by giving too much emphasis to public education, that will limit the ability of private schools to function, and to function with independence, and so on.

And this is a real concern, but actually, the Rebbe kind of dismissed, I was actually very surprised. This is one of the most surprising things that I found when I was working on the book, is that in 1979 when Jimmy Carter was advocating, created a plan to split what was then the Department of Health, Welfare, and Education all rolled into one, he wanted to create an independent Department of Education. And this would centralize all the federal offices into one cabinet-level office, and it would give a new prestige to education, and give new budgetary power. As soon as you centralize something, it just makes everything much more efficient and work better, and gives it that weight and clout, political clout, that it doesn’t necessarily have when it’s just a division of another department.

So in one talk, which the Rebbe gave on Yud Shvat, which Yud Shvat is, the tenth of Shvat is when the Rebbe, himself, accepted the leadership back in 1951. And the year before that is the anniversary of his predecessor’s passing. So it’s a very important day for the Rebbe and for Chabad, but he devoted an entire farbrengen on the tenth of Shvat in 1979, it might’ve already been 1980, no, I think 1979. The years cross over with the Jewish years, but I’m pretty sure 1979, to advocating on behalf of the president, advocating that this is actually a good plan and we should get behind it. And in that talk, he actually dismissed the concern that this could put religious schools at a disadvantage. In a way, that seems very counterintuitive, but I think the principle behind that was one which the Rebbe articulated on other occasions, that when it comes to leadership, to be a leader means to set aside the needs and concerns of your particular constituency and think about what’s needed for the greater good of the society.

And so, in this case, the Rebbe felt, and the Rebbe expressed this in very strong terms, and he even gave out a memo, a memorandum, detailing the particulars of why he felt this would be an important policy that, if education was well-funded, if teachers were well-paid, if the schools had all the resources they needed, that would just create such a strong feeling of integrity for the whole country. The whole country, in every other respect, would be strengthened. He said you wouldn’t need to invest so much in policing. You wouldn’t need to invest so much in healthcare, because education would just raise the level of social success to a much higher level, overall.

David Bashevkin:

And the Rebbe connected this to policing.

Eli Rubin:

Yes.

David Bashevkin:

It’s like something that we heard after the George Floyd murders, talking about police reform and criminal justice reform. And it’s always fascinating to me that the Rebbe was so interested in these, but he was kind of saying that if you heal society a little bit more, then the enforcement –

Eli Rubin:

Exactly.

David Bashevkin:

Wow.

Eli Rubin:

Then the problems go away. And another thing he said is that the military budget wouldn’t need to be so big because, if the integrity of the United States was that much stronger, people would be less interested in going to war. They would see that this is a strong society. You don’t mess with a strong society, which has its integrity intact, which socially has cohesion. But there’s another dimension of all this, of education, which is, again, the spiritual dimension. And that goes to the moment of silence, which the Rebbe advocated in public schools. So in addition to just –

David Bashevkin:

Meaning, during the time when they were talking about, they were going to remove the prayer in public schools, and there were people, and the Rebbe wrote about the importance of keeping it there. The Rebbe offered a really brilliant idea of, instead of totally removing the mention of any prayer at all, the Rebbe had a different suggestion. What was that?

Eli Rubin:

So the Rebbe’s alternative was a moment of silence, because a moment of silence doesn’t have any particular religious content. In fact, it doesn’t have any content at all. So there’s two advantages that the Rebbe saw in the moment of silence as opposed to a nondenominational prayer, which he had earlier advocated, and then, as you said, once it was chucked down in the Supreme Court, he moved to the moment of silence, which he saw as actually more advantageous. And it’s more advantageous, number one, because there’s no content, so students have to think for themselves. This opens a space in which, instead of the teacher feeding the student information and saying, “This is what you’ve got to say. This is what you’ve got to think,” there’s this blank space which the student has to be creative, has to think, “Okay, what is valuable to me?”

And the second dimension of that, second advantage of that was that it would also involve parents and the larger family network in the intellectual process, whereas before, the Rebbe actually put it this way, that before, a parent would send a student, his kids to school, or her kids to school, with a sandwich, but not with anything of value, not with anything of intellectual weight, not with any kind of moral ideal. Just go to school, eat your sandwich. So the relationship between the parent and child was kind of purely material. And education was entirely left to the school, to the teachers, and education also became purely material, because it just became about surviving in the economy. Can you be a valuable cog in the capital framework of keeping businesses going and can you therefore survive? So it’s purely reduced to a material set of values, whereas by creating this moment of silence, it opens up a dialogue where the parent has to think, “What do I want my child to think about at that time?” The student will ask their parent, “I have this moment of silence. What should I think about?”

David Bashevkin:

“What should I think about?” Beautiful.

Eli Rubin:

Well the parent can initiate it. And they can have discussions about what is valuable. What do you want to be reflective about?

David Bashevkin:

And that moment of silence creates a connection where a child could come to a parent and say, “In addition to my sandwich, I want a spiritual nourishment.”

Eli Rubin:

Exactly.

David Bashevkin:

“I want to know what I should be thinking about during that time.”

Eli Rubin:

For the Rebbe, this is really about changing the whole calculus, the whole meaning of, what is education. Philip calls this the post-secular turn, that moving education beyond a purely secular concept and bringing in another set of values beyond the purely material. And this, again, goes back to the idea of the vertical dimension, that this is not just about society. It’s about inserting God in society, bringing that kind of vitality that has a meaning, that has a value which is more absolute than just the narrow finite relations between finite human beings.

David Bashevkin:

And that values-driven education, in the Rebbe’s view, could be society’s best defense, meaning it will trickle down and help criminal justice and policing.

Eli Rubin:

Absolutely.

David Bashevkin:

What an absolutely fascinating idea.

Eli Rubin:

But criminal justice was something that the Rebbe also devoted a lot of attention to in its own right, besides for his discussions about education and the moment of silence. Already, before he became Rebbe in 1950, he articulated a critique of the penal system, the prison system in America, and in general, saying that this had no place, from a Torah perspective. There’s no such thing as prison as a punishment in the Torah. And essentially articulated a critique around the idea that a human being has value, so long as the person is alive, so long as God has given somebody life, that means that they have a divine mission in the world. They have a purpose. And that purpose is not to be segregated from the rest of society. It’s to make a contribution to society.

So again, he had this nexus of the social, the mystical or the divine, and the individual. The individual isn’t just in relation to society. If a person is just measured by their social worth, well if they committed a crime and they’ve broken the social contract, so they’re not of value to society. Put them away. But when you introduce the vertical dimension, that there’s God here, and God is creating this person, that means God still has hope for that person. And if God has hope for that person, if God has a mission for that person, then we should also invest our hope in that person.

So the Rebbe wanted to turn around the whole idea of criminal justice and put its focus on rehabilitation. And he also connected it to education, that rather than, he expressed this in a meeting he had, an encounter, when George Weinstein, who’s still around and still on the federal bench, who’s an activist judge, Jewish judge in Brooklyn, he, Weinstein has been an activist judge in the sense that he’s really been an advocate for sentencing reform and for rehabilitative sentencing. And when he came to the Rebbe, I think in 1989, they’d already been in touch before, but this was in a face-to-face encounter at [inaudilbe], a famous –

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. Those lines on Sunday, sure.

Eli Rubin:

On Sundays. And he said to the Rebbe, “I’m going to speak to a group of prosecutors and I’m going to talk to them about your ideas for rehabilitative sentencing.” And the Rebbe said to him something like, “I don’t want them to just be my ideas. I want you to endorse them, as well.” And then the Rebbe said, in the language of yehi ratzon, “May we soon see the day when we do not need prisons at all and we will just have preventative education.” So there you see that link between education, that education has a preventative element to it that, if education is sound, then you won’t need some of the other mitigating factors that we use kind of post-factum. Once we have problems, we try and put the band-aid on. We start putting people into prison. Well, education can preempt that, but even when we are in a post-factum state, when there are issues, when there are crimes being committed, the Rebbe wanted the focus to be on rehabilitation, that I’m building off a person’s sense of being a human being with a mission, in the image of God with a mission, and not, God forbid, that the prison system, as it so often does, puts people down, shoves them down, makes them feel inhuman and actually reinforces the cycles of bad. The Rebbe wanted to reverse that and create a situation where you have cycles of good.

David Bashevkin:

So we’ve been talking, we spoke about economic justice and criminal justice. There’s one area, I don’t know if you have time, where if you could touch upon it. I think, especially in the moment that we’re in now, and especially the lens through which people think about Chabad and specifically Crown Heights, I was wondering if the Rebbe ever spoke about it. And that’s racial justice. I think a lot of times, when people talk about racial justice vis-a-vis Chabad, it’s seen in a very ugly light, particularly what was happening in the early ’90s during the Crown Heights riots. Without going into the politics and mechanics of Crown Heights, of the riots in particular, I’m wondering if the Rebbe ever spoke broadly about racial justice.

Eli Rubin:

Since you bring this up on the day that we got the news that David Dinkins, the former Mayor of New York, actually passed away this morning or last night, so he was the mayor during that time, and he visited the Rebbe on several occasions. And I believe, on one occasion, there’s a video of this, and if I have it right, it’s during the riots or after the riots, and the Rebbe says to him something to the effect of, again, I’m quoting from memory, so I might not have the exact formulation precisely, but he says that there are no two sides. We are one community, one city. So that, again, goes to that sense. As I mentioned before, the Rebbe’s concept of leadership was, and I think the Rebbe says on the one mayor, which is emphasizing this idea of leadership, to be a leader means to transcend the limitations of your own constituency and to realize that we’re all part of one society and, therefore, we’ve got to put the needs of the greater whole ahead of our own.

And I think that’s often missing from these kind of conversations, where there’s the us and them, us versus them. And the Rebbe really wanted to overcome that sense of division, that sense of otherness, and realize, no, we are one. Yes, of course, everyone has their unique contribution, everyone has their unique history, and whether it’s their unique history of oppression, their unique history of suffering, but also their unique culture, their unique gifts, their unique perspective, their unique understanding. There’s the uniqueness and then there’s the integrity of the whole.

And I think that’s really what the Rebbe wanted to bring to the foreground; that sense, on the one hand, the Hasidic community is the Hasidic community and the black community is the black community, and the blacks should not be made to become Jews and the Jews should not be made to adapt. We’re not talking about cultural appropriation here. That’s definitely not on the agenda. Everyone has their unique traditions, their unique culture, and that should be preserved, but at the same time, there’s the sense of being part of a single community in a single city, a single society. And in that, we have to emphasize the integrity and see what the others need, and not just put our own concerns at the fore.

David Bashevkin:

This notion, and really, this book, I find so deeply moving, talking about social cohesion, seeing spirituality, God through people, through society, through the collective, is something that in your book and through the Rebbe’s teachings I found so incredibly moving. And I think now, in the moment that we’re in in this modern world in 2020, with all these factions and divisiveness, I think it’s the perfect moment to really embrace the social vision. Not the book, you should definitely buy it, but the larger social vision of being able to see that spirituality and godliness that exists throughout the landscape of society.

I always end my interviews with a little bit of whimsy. And we can go through these as quickly as you’d like. My first question is, aside from this wonderful book, which we’ve plugged a great deal, if someone were to want to understand a little bit more about the Chabad approach to social action, to seeing people, what book would you recommend?

Eli Rubin:

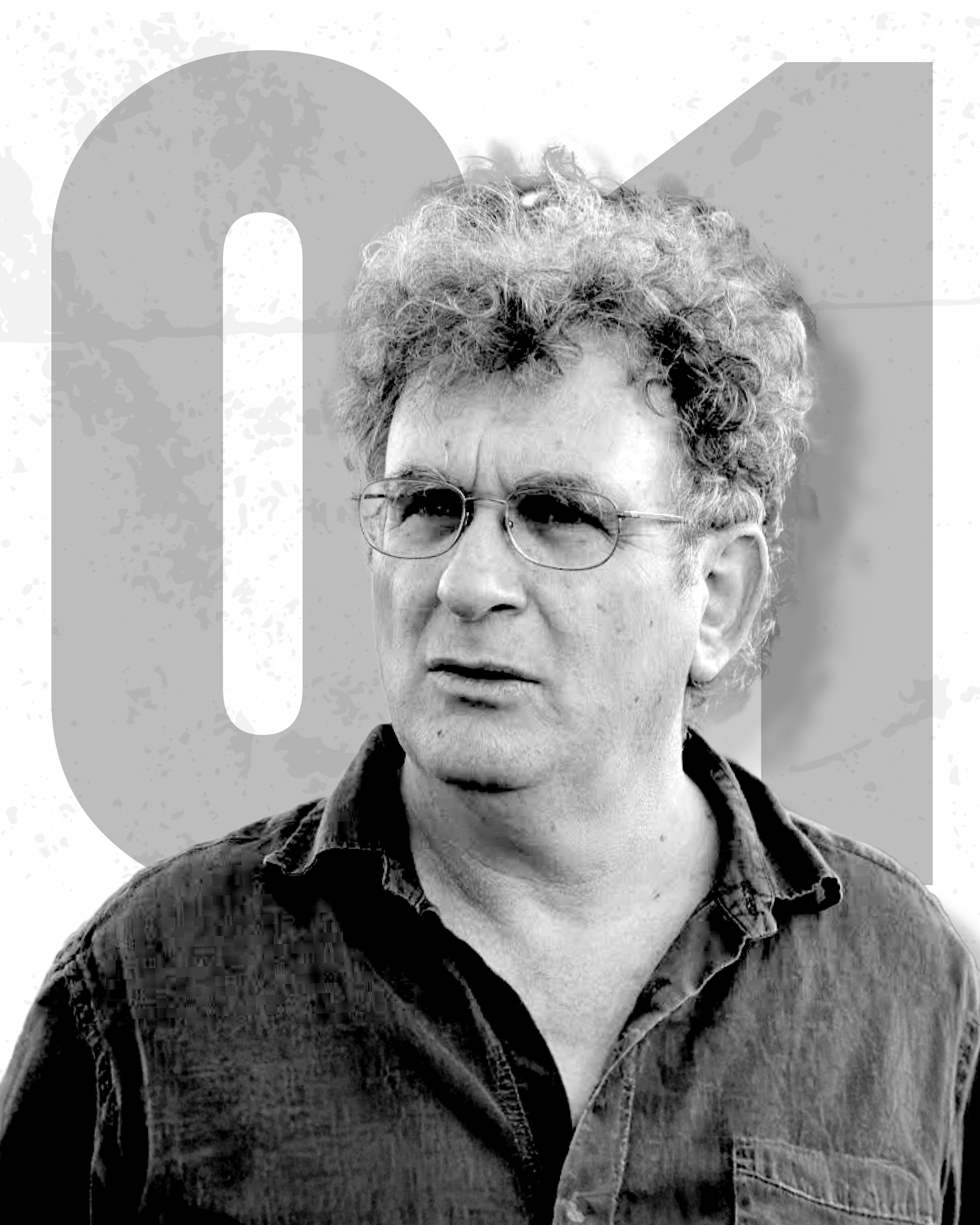

So I would recommend Hasidism Beyond Modernity: Essays in Habad Thought and History, by Naftali Loewenthal. Naftali Loewenthal is a teacher of mine. He’s a great scholar of Hasidism. He’s a great Hasid in his own right. And this book is a compilation and a redoing of some of his most important articles, but when they’re all brought together, and with the new pieces that he’s added to it and updating, it really creates a kind of schematic view of Chabad thought and history, from beginning to end, with an emphasis on bringing together opposites, how Chabad so often brings together the rational and the mystical, the universal and the particular, modernity and tradition, the past and the future. And that’s reflected in the title, Hasidism Beyond Modernity. This is something that carries through beyond the present moment. There’s a very futuristic dimension to Hasidism, a vision for an ideal that has not yet been reached. So it’s really a great book. And I think it, in a way, complements the work that we did in Social Vision, and also has a very kind of personal dimension to it, as well. His introduction is a memoir of his own journey, as a scholar and as a Hasid. So it’s a really powerful and important book.

David Bashevkin:

I think that’s a great recommendation and we’ll have links to it on our site. If someone were to give you a great deal of money that allowed you to take a sabbatical and write a PhD, what do you think the subject of your dissertation would be?

Eli Rubin:

I actually am writing a PhD at the moment, but nobody’s yet given me any money. So if any listeners out there want to throw some money my way and sponsor and give me a sabbatical so that I don’t have to work a full-time job and do the PhD and pay for the PhD on the side, that’d be great. And the title of my PhD is Tzimtzum in Chabad Hasidism. And that refers to the mystical concept of tzimtzum, which goes way back to rabbinic midrashic sources, but it’s really articulated in a whole new way by Arizal.

David Bashevkin:

And tzimtzum means to constrict?

Eli Rubin:

It means to constrict, to contract. Some would say to withdraw, although that’s a debated translation, or to conceal. And there’s all kinds of debates about the meaning of tzimtzum. It’s a very hot topic in both the academic world, I just heard a talk yesterday from Paul Franks at Yale University about how tzimtzum became a concept which the German idealists used, actually, to create the foundation for basic concepts of human rights. So that actually really feeds, it’s a great link. I was really happy to hear that because it linked my work on tzimtzum to Social Vision.

David Bashevkin:

That’s like taking of mystical notion to a social translation.

Eli Rubin:

Which is a perfect –

David Bashevkin:

So we are excited to read that. And I hope that some generous listener gives you that money so you could take that sabbatical, because I think that concept, and the way that you weave, in general, mystical ideas being manifested in society and in people and in the life that you live every day is what I think makes your work so incredibly valuable. My last question is that I’m always so curious with people’s routines and schedules. My dear friend, Rabbi Eli Rubin, what time do you usually go to sleep and what time do you usually wake up in the morning?

Eli Rubin:

At the moment, the schedule that I’m on now is that I try to get to bed before midnight, or even, if I can, before 11:30. It doesn’t always work. It doesn’t always happen that way. And I get up at about 10 past six.

David Bashevkin:

Okay.

Eli Rubin:

But by inclination, however, I’m a night bird, and I would work all night if I could and sleep late in the morning. And so if my kids don’t need to go to school or if there are other allowances being made, then my schedule will look very different, indeed.

David Bashevkin:

I am exactly the same. If it were up to me, I would do three to nine. I think that’s my sweet spot.

Eli Rubin:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Three to nine.

Eli Rubin:

I would go with that.

David Bashevkin:

I think that’s what it would be.

Eli Rubin:

About 11 o’clock, my brain kind of switches on, like, “Now I can work.”

David Bashevkin:

Exactly, exactly. Rabbi Eli Rubin, thank you so much for taking the time to speak. It is such a privilege and a pleasure speaking with you today.

Eli Rubin:

Thank you very much. It’s been great.

David Bashevkin:

There is something about the way Rabbi Eli Rubin presents the thought of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, about this mystical idea about seeing God through people, about seeing God through the everyday lives of others that I have always found so deeply moving. I was scared off from his book when it first came out. It looked, even to me, a little bit too dense, a little bit too intense, but it’s so deeply moving and it shifts the conversation about what social justice can be in the Jewish world. So I urge all of you, get a copy, read it, connect to Eli Rubin. You can find him online, all over the place on Chabad.org, and of course on Twitter @Eli, and the little underscore, Rubin. Please check him out. His ideas, his books, and him as a person, are all so wonderful, amazing, and, frankly, deeply moving.

So thank you so much for listening. It wouldn’t be a Jewish podcast without a little bit of shnorring, so if you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe, rate, and review. Tell your friends about it. It really helps us reach new listeners and continue putting out great content. If you’d like to learn more about this topic or some of the other great ones we’ve covered, be sure to check out 18Forty.org. That’s the number 1-8 followed by the words Forty, F-O-R-T-Y.org. You’ll also find videos, articles, and recommended readings. Thank you so much for listening and stay curious, my friends.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

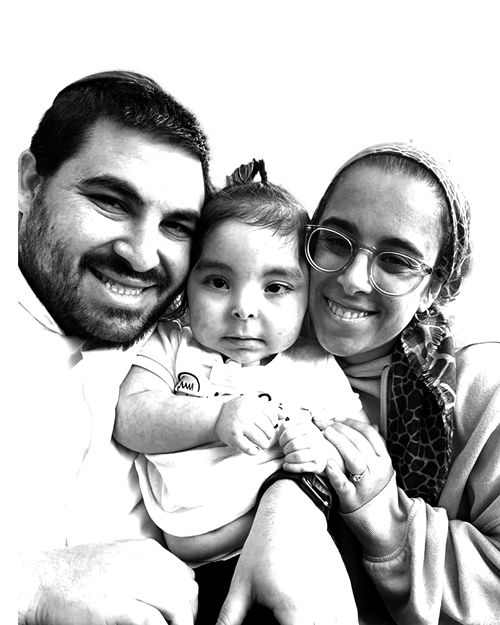

Hadas Hershkovitz: On Loss: A Husband, Father, Soldier

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Hadas Hershkovitz, whose husband, Yossi, was killed while serving on reserve duty in Gaza in 2023—about the Jewish People’s loss of this beloved spouse, father, high-school principal, and soldier.

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Elissa Felder & Sonia Hoffman: How the Jewish Burial Society Cares for the Dead

Elissa Felder and Sonia Hoffman serve on a chevra kadisha and teach us about confronting death.

podcast

How Different Jewish Communities Date

On this episode of 18Forty, we explore the world of Jewish dating.

podcast

Red Flags: A Conversation with Shalom Task Force Featuring Esther Williams and Shana Frydman

We have a deeply moving conversation on the topic of red flags in relationships.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Shlomo Brody & Beth Popp: Demystifying Death and the End of Life

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Shlomo Brody and Dr. Beth Popp.

podcast

‘Everything About Her Was Worth It’: The Life of Yakira Leeba Schwartz A”H

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Yisroel Besser, who authored many rabbinic biographies and brought David Bashevkin to Mishpacha magazine, about sharing Jewish stories.

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Benny Morris: ‘We should have taken Rafah at the start’

Leading Israeli historian Benny Morris answers 18 questions on Israel, including Gaza, Palestinian-Israeli peace prospects, morality, and so much more.

podcast

Rabbi Meir Triebitz: How Should We Approach the Science of the Torah?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rabbi Meir Triebitz – Rosh Yeshiva, PhD, and expert on matters of science and the Torah – to discuss what kind of science we can learn from the Torah.

podcast

Anshel Pfeffer: ‘The idea that you’ll obliterate Hamas is as realistic as wanting to obliterate Chabad’

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu did not surprise Anshel Pfeffer over the last 17 months of war—and that’s the most disappointing part.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Larry and Tzipora Rothwachs: Here Without You — A Child’s Eating Disorder

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Larry Rothwachs and his daughter Tzipora about the relationship of a father and daughter through distance while battling an eating disorder.

podcast

Anita Shapira: ‘You cannot wipe out Hamas’

Leading Israel historian Anita Shapira answers 18 questions on Israel, including destroying Hamas, the crisis up North, and Israel’s future.

podcast

Talia Khan: A Jewish Israel Activist and Her Muslim Father

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Talia Khan—a Jewish MIT graduate student and Israel activist—and her father, an Afghan Muslim immigrant, about their close father-daughter relationship despite their ideological disagreements.

podcast

Frieda Vizel: How the World Misunderstands Hasidic Jewry

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Frieda Vizel—a formerly Satmar Jew who makes educational content about Hasidic life—about her work presenting Hasidic Williamsburg to the outside world, and vice-versa.

podcast

Gadi Taub: ‘We should annex the north third of the Gaza Strip’

Gadi answers 18 questions on Israel, including judicial reform, Gaza’s future, and the Palestinian Authority.

podcast

Lizzy Savetsky: Becoming a Jewish Influencer and Israel Advocate

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Lizzy Savetsky, who went from a career in singing and fashion to being a Jewish activist and influencer, about her work advocating for Israel online.

podcast

Mikhael Manekin: ‘This is a land of two peoples, and I don’t view that as a problem’

Wishing Arabs would disappear from Israel, Mikhael Manekin says, is a dangerous fantasy.

podcast

Yishai Fleisher: ‘Israel is not meant to be equal for all — it’s a nation-state’

Israel should prioritize its Jewish citizens, Yishai Fleisher says, because that’s what a nation-state does.

Recommended Articles

Essays

This Week in Jewish History: The Nine Days and the Ninth of Av

Tisha B’Av, explains Maimonides, is a reminder that our collective fate rests on our choices.

Essays

I Like to Learn Talmud the Way I Learn Shakespeare

If Shakespeare’s words could move me, why didn’t Abaye’s?

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

Fighting for My Father’s Life Was a Victory in its Own Way

After losing my father to Stage IV pancreatic cancer, I choose to hold onto the memories of his life.

Essays

Books 18Forty Recommends You Read About Loss

They cover maternal grief, surreal mourning, preserving faith, and more.

Essays

Benny Morris Has Thoughts on Israel, the War, and Our Future

We interviewed this leading Israeli historian on the critical questions on Israel today—and he had what to say.

Essays

Why Reading Is Not Enough for Judaism

In my journey to embrace my Judaism, I realized that we need the mimetic Jewish tradition, too.

Essays

A Letter to Children Estranged From Their Parents

Children cannot truly avoid the consequences of estrangement. Their parents’ shadow will always follow.

Essays

‘The Crisis of Experience’: What Singlehood Means in a Married Community

I spent months interviewing single, Jewish adults. The way we think about—and treat—singlehood in the Jewish community needs to change. Here’s how.

Essays

3 Questions To Ask Yourself Whenever You Hear a Dvar Torah

Not every Jewish educational institution that I was in supported such questions, and in fact, many did not invite questions such as…

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

Do You Need a Rabbi, or a Therapist?

As someone who worked as both clinician and rabbi, I’ve learned to ask three central questions to find an answer.

Essays

Between Modern Orthodoxy and Religious Zionism: At Home as an Immigrant

My family made aliyah over a decade ago. Navigating our lives as American immigrants in Israel is a day-to-day balance.

Essays

Do We Know Why God Allows Evil and Suffering?

What are Jews to say when facing “atheism’s killer argument”?

Essays

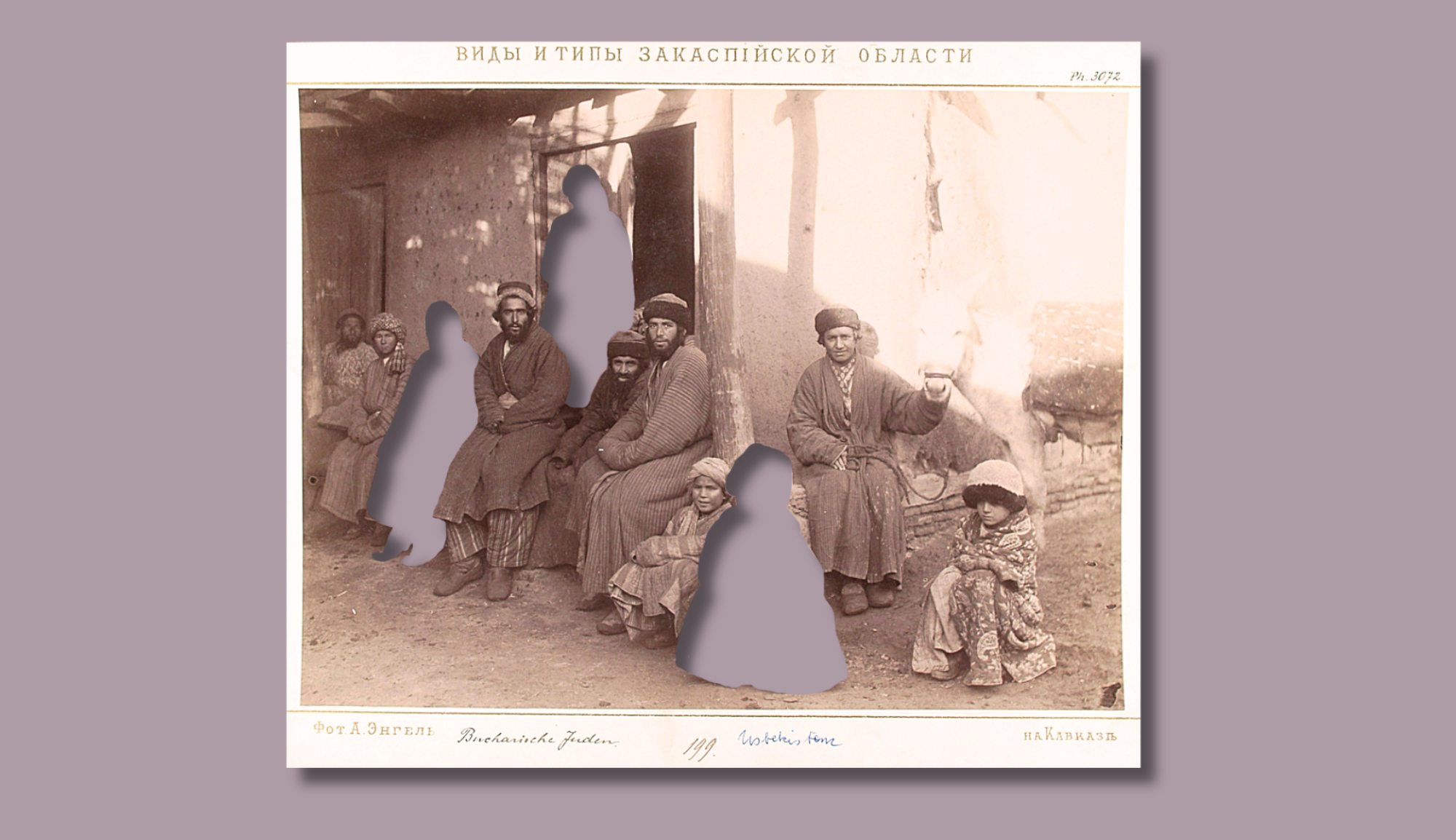

The Erasure of Sephardic Jewry

Half of Jewish law and history stem from Sephardic Jewry. It’s time we properly teach that.

Essays

From Hawk to Dove: The Path(s) of Yossi Klein Halevi

With the hindsight of more than 20 years, Halevi’s path from hawk to dove is easily discernible. But was it at every…

Essays

Judith Herman Is Giving Voice to Survivors

Dr. Judith Herman has spent her career helping those who are going through trauma, and has provided far-reaching insight into the field.

Essays

‘Are Your Brothers To Go to War While You Stay Here?’: On Haredim Drafting to the IDF

A Hezbollah missile killed Rabbi Dr. Tamir Granot’s son, Amitai Tzvi, on Oct. 15. Here, he pleas for Haredim to enlist into…

Essays

The Hardal Community Explained: Torah, Am Yisrael, and Redemption

Religious Zionism is a spectrum—and I would place my Hardal community on the right of that spectrum.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits’ Complicated Portrait of Faith

Meet a traditional rabbi in an untraditional time, willing to deal with faith in all its beauty—and hardships.

Essays

How and Why I Became a Hasidic Feminist

The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s brand of feminism resolved the paradoxes of Western feminism that confounded me since I was young.

Essays

When Losing Faith Means Losing Yourself

Elisha ben Abuyah thought he lost himself forever. Was that true?

Recommended Videos

videos

Mysticism

In a disenchanted world, we can turn to mysticism to find enchantment, to remember that there is something more under the surface…

videos

18Forty: Exploring Big Questions (An Introduction)

18Forty is a new media company that helps users find meaning in their lives through the exploration of Jewish thought and ideas.…

videos

Talmud

There is circularity that underlies nearly all of rabbinic law. Open up the first page of Talmud and it already assumes that…

videos

The Hasidic Rebbe Who Left it All — And Then Returned

Why did this Hasidic Rebbe move from Poland to Israel, only to change his name, leave religion, and disappear to Los Angeles?

videos

Did Judaism Evolve? | Origins of Judaism

Has Judaism changed through history? While many of us know that Judaism has changed over time, our conversations around these changes are…

videos

Jonathan Rosenblum Answers 18 Questions on the Haredi Draft, Netanyahu, and a Religious State

Talking about the “Haredi community” is a misnomer, Jonathan Rosenblum says, and simplifies its diversity of thought and perspectives. A Yale-trained lawyer…