Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt: Non-Fiction

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt – journalist – about her relationship with writing.

Summary

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt – journalist – about her relationship with writing.

Avital’s writing has appeared in publications such as the New York Times and Haaretz, granting Avital an important voice on contemporary Jewish life. As a lifelong writer, she has found inspiration in a variety of arenas, like reporting, Judaism, and advocacy.

- What inspired Avital to start writing, and how did she turn it into a career?

- What are some of the challenges of publishing in the public eye?

- How does Avital get ideas about what to write about?

- Why does she find it meaningful?

Tune in to hear a conversation on non-fiction writing, and to hear about her favorite non-fiction reads.

References:

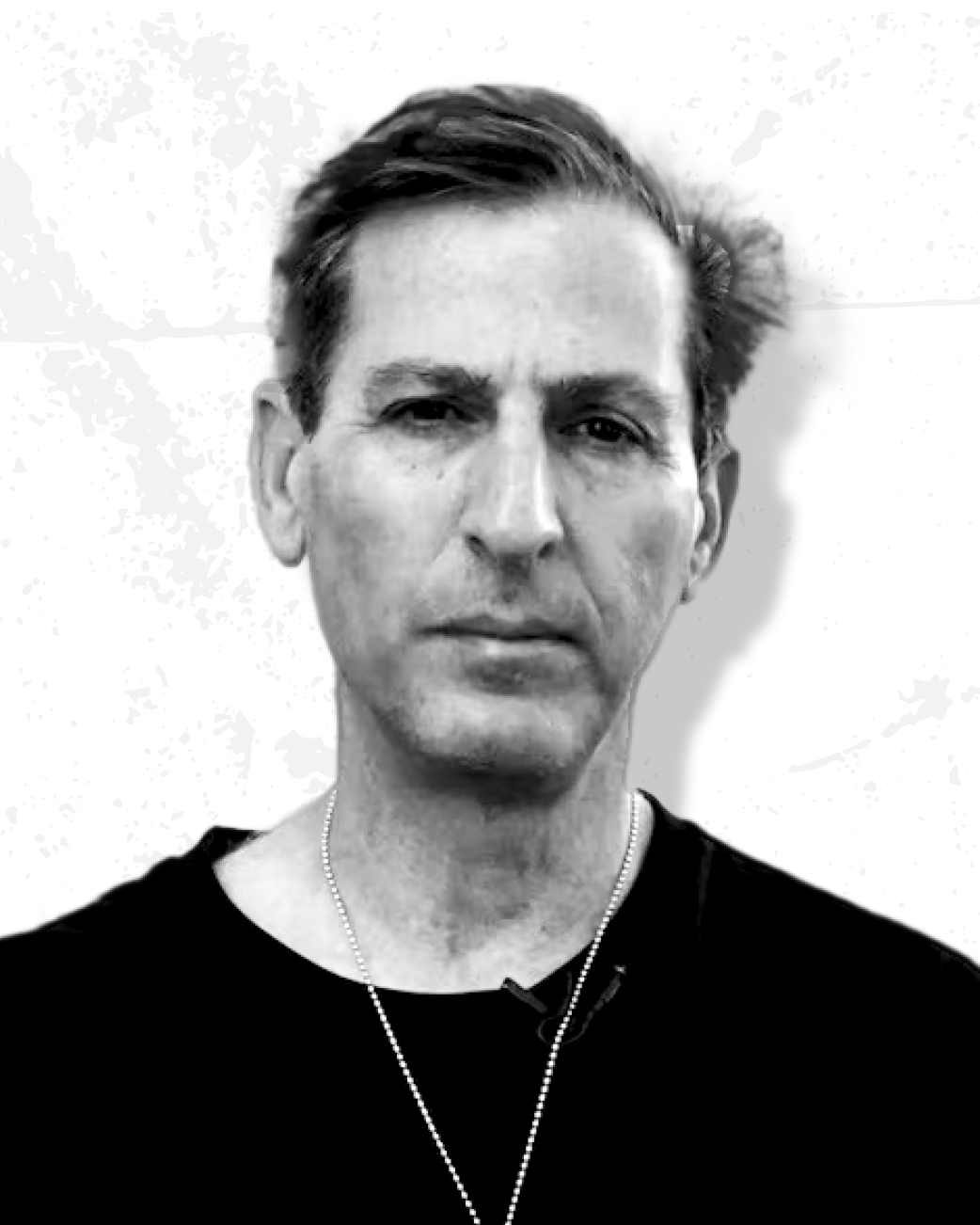

Tefillin in a Brown Paper Bag by Rabbi Emanuel Feldman

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt is a writer living in New York City. Her work, often deep explorations of religious society, has appeared in the New York Times, Foreign Policy, Vox, Vogue, and more. Avital has worked as an editor at the Forward, as well as a reporter for Haaretz. Avital does pastoral work alongside her husband Rabbi Benjamin Goldschmidt in Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Avital joins us to talk about her favorite nonfiction reads on religious life in a contemporary world.

Transcript

David Bashevkin:

Hello, and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast, where each month we explore a different topic balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host, David Bashevkin, and this month we are having a special summer series where we explore Jewish ideas, Jewish portrayals, religious portrayals in fiction, nonfiction, and documentary filmmaking. I’m so excited to share this series with you. And this podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big juicy Jewish ideas. So be sure to check out 18Forty.org where you can find videos, articles, and recommended readings.

So I am so excited to introduce our summer series. I was thinking, what could 18Forty do to contribute to people’s summertime off, help exhale a little bit? A lot of our topics can sometimes be a little bit on the heavy side, and just imagining somebody sitting beachside or going bike riding, listening to, I don’t know, some professor or philosopher talk about Jewish studies or some family negotiating their religious differences, it just was a little hard for me to imagine. So I wanted to do something special, particularly for the summertime.

And I don’t know about you or what you do over the summertime, but there’s no question that for me, the summer is all about sitting outside with books, articles, getting to read, sitting at night, getting to watch something that’s interesting, that’s exciting, that’s uplifting. And I decided that what I thought we could do over the next few weeks is explore depictions of religious ideas, Jewish ideas, in different mediums, going through non-fiction, fiction, and documentary filmmaking. And explore a little bit about how religious change, religious ideas, religious growth, particularly within the Jewish community, are depicted within these different mediums. And I am so excited about the discussion today, particularly about nonfiction writing, because I think for myself, what I enjoy reading most is nonfiction.

As I’ve mentioned I think a few times, I’ve probably read less than a handful of fiction books in the last 20, 30 years. Not 30 years, the last 20 years at least. I grew up reading John Grisham and Michael Crichton. That was very exciting but at some point I just began reading nonfiction. And part of what I think that change was is that non-fiction writing really went through a renaissance. It really allowed a narrative storytelling that was usually associated with fiction writing, nonfiction became more and more just this area of people transmitting stories and ideas that actually happened that I was just drawn to it. And for myself, when I go on vacation, I print out these long-form articles from my favorite publications. I’ve listed my favorite New Yorker articles, Atlantic articles, books, or whatever it is, and I just sit and I enjoy reading.

Not everybody does, so if you do, I apologize, you can always go back and look at some of our previous episodes. But this is going to be a great deal about writing, but particularly about writing and the Jewish community. I think the article that made me think most about the art of writing is an article that I’ve quoted 101 times and things that I’ve written. And it’s a book by the former editor of Tradition Magazine, Rabbi Emanuel Feldman, was actually the brother of the Rosh Yeshiva Rabbi Aharon Feldman when I was studying in Ner Yisroel.

Rabbi Emanuel Feldman was a long-serving editor for Tradition Magazine, he’s collected his articles in books, and he has these absolutely brilliant takes, and so many of them have to do with how we depict and share our community. There’s one article in particular that I think about constantly when it comes to writing, and that is his article “Tefillin in a Brown Paper Bag,” where he writes as follows. “The use of deficient language has practical negative consequences as well, for it prevents us, the Jewish community, from preaching to anyone but the Orthodox choir.”

Rabbi Emanuel Feldman, whose writing in Tradition and talking about ideas from within the Orthodox Jewish community is emphasizing the need to be able to develop ideas that can reach people outside, who didn’t grow up in an insular Yeshiva world necessarily, or went to seminary, Yeshiva, and all of this, but can reach beyond. He writes as follows, I’ll continue: “Intelligent, educated, non-Orthodox Jews will surely be put off by argot which passes for much of the Torah Judaica today.” I love that he used the word “Argot,” A-R-G-O-T. I do not see that word very often. I have no idea if I’m pronouncing properly.

“By in large, we do not quite literally or illiterately speak or write their language, for jargon by definition is a simple elemental form of communication which includes only the initiated and eliminates everyone else from the discussion. It is hard to imagine that any thinking individual can be persuaded of the depth of Torah when quite beyond grating misusages, such as ‘being that’ instead of ‘since,’ ‘comes to tell us’ instead of ‘informs us,’ ‘brings down,’” this is my favorite, “instead of ‘cites.’ The ideas of Torah are presented in jejune and puerile language.” I may be mispronouncing a lot of these fancy words, but as I’ve mentioned before, whenever somebody mispronounces a word it’s usually because they’ve only learned it through writing itself, reading.

“This is a pity,” he writes, “for Torah is precious enough to deserve elegance, grace, sophistication, and precision. After all, we don’t wrap our Tefillin in brown paper bags, or bind our Sifrei Torah with coarse ugly ropes. A worldview which is inadequately articulated not only fails to communicate, but repels those whom it would reach. And his argument, which I love that imagery, we don’t wrap our Tefillin in brown paper bags or bind our Sifrei Torah with course ugly ropes. About the encasing of our ideas, about writing with a certain clarity, a certain precision, a certain majesty and beauty needs to reflect the very content of the ideas we’re sharing.

It’s not enough to share beautiful ideas and ugly cases, but the very medium through which we share our ideas, the grammar, the words, the syntax, and the structure, all play a role in reflecting the very majesty of Torah that we are trying to share. And you should absolutely read that article, it’s worth reading. And part of why I am so excited about my conversation today with Mrs. Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt. I may have mispronounced her name also. I don’t often call her Chizhik. I believe that’s how she pronounces it. I’m sure you can write it. But she is a dear friend of mine and I would say a mentor of sorts, which we discuss in my own writing when I share ideas. She’s on that very short list of people who I send articles to and ask for her comments. And she’s been incredibly helpful to me.

I think any time that you write, it is literally an act of emunah. It is an act of faith. Any act of creativity is an act of faith, but it’s not just an act of faith in that we look to God or you look to some higher power asking you to give out your idea, it’s an act of emunah and faith in that it’s both faith in God that that inspiration and creativity will emerge, it’s about a certain faith in yourself, in your ability to have the strength, to share ideas and be subject to criticism and feedback and all that other stuff. But writing and sharing ideas more than anything else is an act of faith in the community itself who you are sharing those ideas with. It’s an act of faith in speaking at a high level with substance, with clarity, and not speaking down, or writing down, in this case, to the communities and people, and individuals, families, who you are trying to reach. I think that’s why I’m so excited to speak with Avital.

Avital, is an incredibly accomplished writer, and what I’ve done, because so much of our interview relates to her process, and the process of writing and how it interfaces with the community, I’ve also asked her to share three recommendations of what our listeners can be reading and thinking about now in the summertime. And we go through three of those, and stick around for the end of the episode, because I am going to share my three nonfiction recommendations about Jewish life at the very end of the episode. Things that you could find online, download, read on the beach, wherever you are, but enjoy them, because what greater joy is there in the summertime than immersing yourself in reading? I’m so happy to introduce my conversation with Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt.

Avital, thank you so much for taking the time to join me today.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

It’s my pleasure. Thank you for having me.

David Bashevkin:

So I wanted to begin, because I know when I write something, and before I’m going to submit it to get it published, there are a few people who I send my own writing around to, and you are definitely at the top of that list. I’ll tell that story in a little bit, of articles of mine that you’ve saved from the trash bin, or from just being far less than excellent. I wanted to begin by talking about you. You’re really a prolific writer. You write in so many different outlets, both Jewish outlets, non-Jewish outlets. But your themes do center around religious subject matter. And I wanted to begin by talking about your writing process. What is your writing process? How do you pick a subject? And like, I’m always curious, where do you write? Tell me a little bit about your writing process. How do you go from a blank page to one of your extraordinarily thoughtful articles?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Thank you. That’s very kind of you. Well, I’ll say like this. I grew up with my father, who is a physicist at the labs, always telling me, “Write what you know.” And I try to write what I live, what I see. I think we all do naturally. It doesn’t mean that everything is for my personal life, of course, but over the years I’ve grown increasingly spurred by readers and by members of the frum community who reach out and say, “This is really interesting, and no one is going to write about it other than you, can you write about it?” So that’s usually how a story comes up.

Sometimes it is something from my personal life, but I think increasingly I like to remove myself from the frame as much as I can, because it’s not about me. It’s about my subjects. I think also many times my subjects come through community work, which I don’t really talk about much publicly, but it’s a huge part of my life. All-consuming in fact. And just sitting in the front row, observing, I interact with dozens of people in real life. Every single week I have a dozen people around my table for every Shabbos meal, and really in every capacity, every single day, I feel like I’m faced with real and fascinating questions about religion, about faith, leadership, politics, ambitions, and sometimes life and death. I feel like life is rich with material and there are stories from every type of angle. In terms of where I write, in the morning—

David Bashevkin:

Like physically, the geography of where you write, when you write? This is what I love hearing about. I hope our listeners do too, but I could talk about this all day.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

I love to listen to this also from writers, and actually I was always very intimidated by writers who write standing. Historically there were a few great writers wrote standing. They had a standing shtender, a standing desk, and I want to get there. At this point I usually write in a coffee shop here in the Upper East Side in the mornings. I have a few spots that are Parisian in style, so I’d like to imagine myself a Hemingway. And afternoons and evenings I write in my study where I am right now. So I look at a nice townhouse and I think it’s pretty quaint.

But I think the truth is a writer is always writing mentally. I’m writing as I walk in the street. And you bet that I am writing in shul in my mind. My mom once scolded me actually for bringing a notebook to a funeral. I just could not hold back, it was a Russian-Jewish immigrant funeral, a relative. There was so much to unpack there. There’s trauma, there’s immigration, there’s assimilation. It’s so interesting, but it’s a chronic problem. And I think the big question is really on Shabbos, what do you do? And Shabbos is really one of the best ideas and I’m sure that’s true for you as well. Because we’re so unplugged and we have that ability to really dig deep. So by the end of Shabbos, I usually have a list of terms that I memorized that I need to jot down.

David Bashevkin:

And do you write initially by hand or on a computer?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

It really depends. I’m not particular about it. I could do anything, I could do it by hand.

David Bashevkin:

You could write by hand?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Yeah, for sure. When I go on vacation, I try to write only by hand because once I’m on a tech device it feels like work. And then actually recently I got an iPad and I use that a lot to write as well.

David Bashevkin:

I can only write lists by hand. So if it’s a grocery list, if it’s a top five list, I could write bullet-pointed lists. That’s really all I can do by hand. I can’t even write a full sentence by hand. Just a few more questions about the process itself. When you finish your first draft, typically, how many drafts are you writing before you send it in to your editor?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

So it really depends on what I’m writing. Straight beat reporting is very formulaic, which is frankly why I left it. I really wanted to experiment more with my craft. I want to be doing reporting, but really focusing more on long-form features that dig deeply into an issue, what it means and why it matters. And I find most reporting is fueled by adrenaline, so you find one source, then another, and you sort of build your way up until you have a story that is hopefully well-rounded and dynamic, and you have the right amount of voices, and sources, and data, et cetera. So, that I find is pretty straightforward. And honestly starting in Haaretz and then going on to The Forward I had this amazing boot camp of learning how to crank that out. And then I taught it in Stern, of course. So I feel like that is a very straightforward process.

The question is more interesting when you come to essay writing, something that’s a little bit more of a step back. It’s quite different. And I find essays usually cook for a very long time. It’s really a chulent, I let it simmer on a low flame for a long time. My next essay is a personal one. It has been several weeks in the works. I write it. I put it down. I come back to it. It’s a process. I have someone else read it. I have another person read it. And others take even longer than that. I have one essay related to women’s issues that I wrote in 20, I want to say it was late… It was 2019 at some point. I don’t remember what month. I was at The Forward. It was a very strong essay. It was sharp, fiery, and I’ll never forget. We had already loaded it into the content management system, and we were about to schedule it for the next morning, or maybe it was already scheduled. It was done. It was edited. Everything was great. It’s going to make a big splash tomorrow. So exciting. And then some things happened in shul that afternoon, and I realized there’s no way I can do this.

I consulted with my husband and we realized it would be too radioactive in that moment of time, and it would have to wait. And Jane Eisner, who was then the editor in chief, walked into my office and asked, “Are we all set for tomorrow to publish?” And I just started crying. And she was so shocked. She totally understood. She nodded, she was like, “Don’t worry about it. Real life comes first.” But it was a very hard moment. And I open this essay still to this day. It’s never been published. Every few months I reread it and I wonder, will I be ready to publish it? When, I don’t know, maybe, but that’s a piece that’s literally two years old that I’m still working on. I feel like I just haven’t come to that point that I’m ready to publish it.

David Bashevkin:

It’s in the slow cooker still. I remember, the article that I was referring to that I really think you saved from oblivion and not having the impact was right when the pandemic began, I wrote an article about spending a Pesach seder alone, and I sent you a first draft, and I remember you looked at it, and you had such brilliant advice. You said, “Your last paragraph is just a flop,” and you said, “that’s always where you flop.” I think it’s because we’re so used to sermons that end with this general blessing, “bimheira biyameinu amen,” the Temple should be rebuilt speedily in our days, and you kind of like give a peace sign and run away from it. And you pushed me to sit with it longer, find a way to wrap this up without getting pedantic or too overt about your message. Let your message sit in your listener’s mind rather than you cramming it down. And I rewrote the entire ending. Now, anytime I write something, I always take a second glance at that last paragraph, which is so often like the belly flop of the writing process, because you’re 90% of the way there.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Yeah. I had one teacher in Bruriah, her name was is Margea Pupko, she’s an amazing English teacher. And she had this term, she would describe it as “cool guy at the party”. In writing, you want to arrive late, and you want to leave early. You want to be the cool guy at the party. You don’t want to belabor your point. And it’s funny, I’ve remembered that term for all these years. And usually when I’m editing, I take out my opening and I cut out the ending. And it’s natural that we do that. As you said, sermons, drashos are written that way. And also just in general, we’re taught in school that you need a beginning, a middle, and a conclusion. But that’s not really how great writing really works.

And I think the other point that you make that really emerges here is that, I believe in assuming that my reader is smart, and respecting my reader. Expecting the reader to be able to read between the lines and what I’m trying to say. I’m not going to lay it all out for you. That’s not my job. That’s the beauty of reading, is processing and trying to understand what the point of this is.

David Bashevkin:

I am absolutely obsessed with that imagery. Cool guy at the party writing. I’m going to take that with me for some time. Let’s start with how you got your start with writing. What do you consider? Because, I know this is a tricky question. Different people may consider different pieces their first published piece. When you look back and particularly about religious and Jewish issues, what do you consider your first published piece?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

I really started publishing very early at the age of 11 or 12 little things, little newspapers locally. So I’m not going to count that, but that wasn’t very formative part of becoming a writer that was learning that to become part of my identity. And also giving you the confidence that you could write that you have something to say at a young age. My first I think published piece that I think made an impact that differentiated itself was a piece I wrote in 2012 for Tablet. I was finishing up Stern at the time and I wrote a very fiery essay called “Tights Squeeze.” I did not come up with that headline, but it was a cold pitch. And it was an essay about sort of the culture. It was focused on girls schools, but it was in the Orthodox community, but it was really a broader point.

The piece was about sort of our culture of stringencies our chumrah culture, where we have to constantly prove to one another how religious we are, how from we are, how stringent. And I argued in the piece that for me, and I wrote it from a very much as a daughter of baalei teshuva, newcomers to religion. My parents became religious as I was growing up. I was very idealistic about our choices as a family and my choices as an individual to be an observant Jew. And for me it was a shocking culture to encounter because I sort of defined modesty not about the details, but rather we should be modest about our piety, We should not flaunt to the world how religious we are and how so strict we are and that this sort of creates a toxic culture.

I wouldn’t have written that piece obviously today. I mean, I think the point still stands, but the style is definitely my style has changed dramatically, but I had all these little fiery anecdotes in which I tried to conjure this culture. And I think it captured something for people where the reaction was overwhelming. It was also around the time of the riots and Beit Shemesh. There was this sort of—

David Bashevkin:

Sure.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

… a lot of tension on the ground if you remember that. So people were very passionate about that issue specifically at that time. And it really struck a nerve. I had never thought that I would write about religion. I had never thought I would write about community issues. I had a teacher in high school who would always say, “One day you’re going to write about this,” and I sort of laughed because I thought it’s just my life, what’s there to write about? It’s just my day-to-day life. And then obviously as I grew older, I realized there’s a lot of material here and there’s a lot that could be here through writing.

So that was my first piece. It was a very shocking experience because I was 20 years old. The piece went viral and this was back when articles went viral on Facebook. And it was like overwhelmed with messages, people writing to me, “thank you. You really captured something I experienced.” I had a lot of messages from people who basically had left community or had changed their observances because of these issues that I outlined. And they said that to me, that this was why they left. And it was an interesting experience. It was very anxiety-inducing because I was just a more private person. And then suddenly I was not. And I was 20 years old and I was in Stern. Like I wasn’t planning on being a rabble-rouser. That was not my plan. But Hashem has his ways.

David Bashevkin:

So you were already coming on to that about, you have really forged a path about what it means to write about Jewish and religious issues. And I wanted to dig a little bit deeper because I know any time a movie comes out or Jews are in the news or any time that there was a depiction of more broadly religious life and more specifically Orthodox Jewish life, there is a visceral reaction of people in the community wanting to see their own experience on the page and the level of scrutiny that your own community can give your own writing is oftentimes much higher level of scrutiny than they would have reading about a different religious community or just a general issue, a political issue. So what do you see as the primary challenges and opportunities of writing about Jewish and religious subjects?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

So I think the challenges are obvious. It actually begins earlier than the publication. It starts with the process. The process itself is challenging especially when you’re doing reporting and people are very uncomfortable talking on the record. Even about very basic things. You could not imagine the amount of people I’ve reached out to, to really talk about something that’s seriously not controversial. And the fear that people have about talking on the record and even anonymously at times, people are just so uncomfortable with that sort of exposure. And it’s legitimate, I’m not going to question that emotion and I won’t pressure people to speak if they’re not comfortable with it, but it’s like pulling teeth at times. So just getting those words, getting other people’s words on the page, not just my own is difficult.

And then of course there’s always the aftermath. There’s the backlash, people feel uncomfortable with exposure as a community, I think we have a siege mentality on some of it I really believe is inherited trauma. I think this constant fear of antisemitism being spurred by something that in the media is sort of a product of that. Of course, I think that it’s still necessary this exposure. And I think some of it is also sort of politicized. It’s politically convenient to be able to say, we shouldn’t talk about anything in our community. No one should know. So those are the obvious challenges. And I’m happy to tell you more about those stories.

The opportunities I’ve realized over time, that because I write about a small enough community, the impact is in a way deeper. I’ve thought about leaving Jewish media. I’ve interviewed this past year with a few major publications non-Jewish for general roles that would be like obvious career boosters, but through that process realized that’s just not what I want to do. I see the impact of my stories in real time, the amount of letters that I get from rabbis, from mental health professionals, from educators about my work, about a story that spoke to them about a story that I tried to capture something that they see in their day-to-day lives. They appreciate that I articulated something or that I shed light on it. And I try to do it in a careful way. And they appreciate that someone is out there doing something and saying something. And you start to realize that the pen is a deeply powerful thing.

I think I was skeptical about its power in the beginning of writing. And now I’m at a point where I see that the real impact it can have for people and sometimes just taking on a big issue and like laying it out, explaining all the factors there, all the political players let’s say. Or sometimes if it’s an essay, if it’s a critical essay, I’m saying something that people may be uncomfortable saying. So there’s so much room for that impact and it’s a real impact. I meet people all the time in real life, not just messages who mentioned an essay that I wrote at some point and that it moved them that it made them think differently. And that is such an incredible opportunity.

David Bashevkin:

Do you have a piece that you are most proud of publishing and do you have a piece that, I’m trying to phrase it the right way, simply put the least proud of publishing or one that got negative feedback that you came to agree with or see your own writing in a different light. You can start with the good stuff if actually…

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

The second one is the thing that comes to mind sooner, the thing I’m most proud of, I can’t really choose.

David Bashevkin:

Well, I noticed that you pin on your Twitter account, you’ve written a lot, you pin a piece that you wrote about davening, about prayer, and I’ve always been struck by the fact that you’ve written and published quite a bit, but the one piece that you pin on your Twitter account, and it’s an important outlet. It’s in Vox. It’s not the most important outlet that you’ve published in. You’ve been published by The Times and other mainstream multiple times and I’ve always looked at that. I’m sorry that I’m giving a Freudian analysis to your pin tweets. That’s a new area of psychological analysis. Now that I’m done with analyzing people’s bookshelves, which I’m doing also simultaneously. But I also analyze people’s pin tweets.

And to me, there’s something very basic, very foundational about that piece of what you’re sharing. That in a way, I don’t know, it’s about prayer, but to me, you pin it because your writing in a way always feels prayerful. That it’s both looking at a community and also praying for whatever issues and personalities that it is covering. There’s an optimism. There is a prayerful aspect to hopefully elevate those stories. I’m sorry if I’m doing a deep Freudian read of that pinned tweet again, but it always struck me that you decided to pin a piece on prayer.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

That’s a very thoughtful interpretation. I appreciate that. Yeah. Well, I love the analysis of pinned tweets. I think people who are not on Twitter don’t understand it, but people who are understand it.

David Bashevkin:

Let me just jump in what that means. That’s the tweet that under your profile, you can pin it. So it always appears immediately under your Twitter profile. I have just shameless plugs to buy my books and read my articles. It’s not classy. I just changed my pin tweet this week. But you have your prayer article, tell me why is that the one that you pinned? Am I correct that maybe something that you’re most proud of?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

I didn’t think of that immediately, but yeah, I think that piece really shares my worldview in a way. Also pinned it on Twitter largely because the article itself talks about social media and how, for me, prayer is in many ways an antidote to what social media I think is doing to us as a society and as individuals psychologically. So I felt like for me being on Twitter it’s very bidieved. It’s not ideal, it’s suboptimal.

David Bashevkin:

The necessary evil.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

A necessary evil. And we could talk more about that too, but for me it’s not something that I really want to be spending time on or investing in, but I know I have to, to an extent. So for me putting that at the top of my profile was almost… Maybe it’s a message to others, but for me, I did it for myself like a reminder like this is not important. This is what happens online. It’s important and it can impact, and it can do great things, but this is not what matters in life. So for me, it’s “da lifnei mi atah omed,” know from before whom you stand. And that was my version of that. The piece itself really speaks about how I think there’s a way to look at prayer in this modern light in a way that I think many millennials might even gain from meditation and all this wellness stuff is on a rise for a reason. And for me as religious Jew, prayer is my answer.

David Bashevkin:

No, I love that because there is a lot of talk about the modern application of Shabbos and how Shabbos is this refuge from technology from social media and what I thought the piece does so beautifully is it, Shabbos is almost the more obvious analogy and it reminds you that you can create that Shabbos experience daily in your life through prayer itself. And as a kind of an epitaph that you kind of place on your social media account as a reminder that that’s a part of the writing process too, not to get dragged into that daily.

I do want to come back to that, but I do want to hear the second part of the question, unless you have another vote for the one you’re most proud of about an article that again, whether it’s least proud of, or one that after criticism and feedback, you look back in it and say, “You know what they were right. My critics were right. I need to re-examine what I wrote there.”

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

I’ll start off by saying, I often find the negative feedback is largely emotional, not always, but largely it is emotional responses. It really deals with the issue at hand.

David Bashevkin:

Let me just flush that out. Meaning it’s not a reaction to what you wrote. It’s the visceral emotional reaction to the subject matter almost.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

To the subject matter, maybe to how it was written, maybe to who was the person behind it, or maybe to what publication it was in. So it could be many different things, but it’s rarely about the main point. And sometimes it will be like, “Well, it was the way you said it and how you did it. It was uncomfortable,” but really just the issue was that I said it. And that also, frankly, that I’m a woman and I don’t like to do that. I don’t like to pull out the misogyny card. I don’t do that frequently, but over the years, I’ve realized like, oh, men can say that and get away with it, no problem. But if I say that, then it’s a problem.

So when people might be uncomfortable that I didn’t couch something with a million disclaimers that make people feel a little bit more comfortable, but writing is not supposed to make you comfortable. That’s not what I’m here for. I’m here to afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted.

David Bashevkin:

Say that again. Say that again, Avital. That was lovely.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Well, it’s not my line. It’s Peter Finley Dunn. Who’s a journalist at the Turn of The Century who said that a journalist’s job is to afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted. And I think that obviously there relates to all journalism, but specifically to community journalism and religious journalism. That is something that we don’t do enough of. And that’s sort of one of my leading mantras and what I try to do. And I get it, it’s very uncomfortable. I, too, would rather just be comfortable and not have to think about things and embrace my privileges, but that’s not what God put us on this earth to do. So having said that, there are certainly moments where I’ve gotten negative feedback where someone said they did something wrong or you included the wrong quote or something. Sometimes I agree but it usually takes me years afterwards to see it in some realizing and maturing. Because in the moment you’re really wrapped up into piece.

There’s one specific piece that I wrote that was actually a conservative take for Haaretz in I think 2013. And it was about a young women who were trying to do traditionally male rituals at the time. I think it was at SAR High School there was a woman who wants to put on Tefillin and there was a scandal at the moment. And I was asked to write a response from an Orthodox perspective. And my argument was that this Teffilin is not the most pressing problem for women today in that Orthodox women faced much greater, more basic challenges in equality and being respected as thought leaders and so on. And that this is, I forgot what the words were that I use, but I was like, that’s not what I want. That feminism is not mine.

And I got criticism actually from sort of, I would say, mainstream Orthodox thinkers, who said that I did not acknowledge the way that halakha and halakhic rituals, establish authority inevitably. And I think they’re absolutely right, but that’s not something I would have understood at that age. I was 22 years old. I had grown up my entire life and all-girls schools, no brothers. I wasn’t in that world to understand it enough. To understand the way that halakha can give that authority and that someone who’s not working within the same religious laws is just disadvantaged at the end of the day in some ways. I’m not saying change the law, but I’m just saying those are the realities. So I stand by that original point which is that religious women face larger challenges than this for the most part, but I should have acknowledged that head on.

David Bashevkin:

I think one of the most jarring pieces that you ever wrote that I come back and think about was the story you did on abortions in the Orthodox community. And I’m curious about what was the feedback backlash from that piece? I mean, that’s a very sensitive subject to reach out to people who have had abortions. That’s obviously treading on extraordinarily sensitive halakhic grounds. And I’m curious in a piece like that, how do you balance your personal religious identity and the piece that you’re sharing with the world? Because they don’t always cohere and it’s not always an opinion piece that you’re writing. You find a way to kind of take an issue and build a narrative around it. So in a piece like that, using that as an example, how did you manage your personal religious identity both in the process and even more so in the aftermath? Because I do think you got a lot of criticism for it.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Well, I don’t remember that criticism, but the truth is I block it out. I don’t keep a tally of it at all. If you do that, you’re lost you won’t get into this work. You won’t do a good job in this. But the piece itself, it’s funny that you asked this question because the thing that pushed me to do it there were two things, two triggers for me with that piece. One was there was sort of, I don’t remember even exactly what was going on, but there was discussion of Roe v. Wade at that moment. And the usual sort of Orthodox pundits were pushing one agenda. And I was watching that online and I was like, this is just very absolutist.

And the other trigger for me was actually watching my husband deal with questions around this topic. This is something that I think any religious woman in childbearing age who has friends who are having children, you know someone who’s had to have a pregnancy termination, it’s not so uncommon. So between just living with many friends who have had to go through this or know someone who went through this, it’s not so unusual unfortunately.

And then also watching my husband get a few shayalos, a few questions within, I don’t remember within that year or so from people I would say very different backgrounds, but people come to a rabbi with these questions, which I thought was also so interesting. Even people who were like less observant who find in that moment, they need pastoral guidance. And looking at it as a woman and as a mother and then also in a way as a rebbetzin, as someone who sees these questions, and who understands the importance of visceral guidance in that moment, and who sees women whose hands have been metaphorically held by that visceral guide. And those stories don’t get told either.

I think often people want to hear the very sensational stories, but what I loved about that piece was not done by me. These were the stories that the women told me. What I loved about it was that the women spoke about going to rabbis and asking for help and asking for advice and that sometimes the rabbis said, “Yes, do it.” Now, we know that if you are someone who lives within the sphere of the rabbi, you understand that behind closed doors there’s a lot of flexibility. Halakha is built to be that way, right. Obviously with great halakhic legal minds, but you understand that the reality behind closed doors is very different from what it said in the public square. And I wanted to try to shine a light on that without having to say state it explicitly. And I think the reaction was… Again, I don’t remember the criticism. I’m sure there was, but—

David Bashevkin:

I don’t think there was criticism to the piece. I think that any time that somebody writes about an issue related to intimacy or something deeply private in the Orthodox community, I don’t think the reaction was to the content. I think the subject matter, I remember was… Maybe criticism is the wrong word. There was like an audible gasp, like we’re writing about this now. And I think there was something very moving about the fact that you gave language to that narrative.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

To be honest, I think a lot of the gasp was not to get political here, but I think we have been inevitably affected by evangelical Christian perspectives on these things and the way that we talk about them and that I think contributes to that gas. I don’t know if it’s necessarily authentic gasp so to speak.

David Bashevkin:

Let’s go back to what has shaped you as a writer. Can you tell me a little bit about who are your writing role models? Who are the ones who shaped the way you approach a piece living or deceased?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Mostly deceased. I grew up reading a lot of classical literature and much of it actually Russian. My parents are from the former Soviet Union and Russian is my first language. So my mother handed me War and Peace at the age of 12 and said read it. And by the way, I was a slacker.

David Bashevkin:

No, I’ve always bragged that I was reading John Grisham at the age of 11 or 12. I certainly was not reading Dostoevsky or-

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Tolstoy.

David Bashevkin:

That’s a whole nother level Tolstoy. Yeah. That’s a whole another level.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

But I was a slacker by the way, because I wasn’t reading it in the original Russian and French and I was ready to get in translation.

David Bashevkin:

Gotcha.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Yeah. I really adored Chekhov. And to, again, if there were the masters of the Russian short story. And I mentioned this because I think this had a huge effect on me more than I could ever realize. I grew up with two very different rhythms of language from an early age. And then three of course. The moment I started learning Hebrew in school and in my family, there was a major focus like with, I think, most Russian-Jewish families on studying literature and memorizing poetry actually. I was never so good about it, but there was like this expectation that children at a family party, it must stand up and recite a poem of Pushkin. A foreign family would have a dvar torah, Russians have a poem said.

I think it seeps into your writing by osmosis, even if you don’t mean it, even poetry, [inaudible] poetry can seep into my English language non-fiction. So I think that was a very formative part of my reading as a child, but also to this day. I loved reading the Yiddish authors Sholem Aleichem, Isaac Babel, Batsheva Singer. I read them in English. And then in Stern I spent a lot of time reading modern Hebrew literature also first in English and then in Hebrew, and actually ended up writing my undergraduate thesis on Amos Oz’s memoir, “A Tale of Love and Darkness.” So that was, I think a huge impact on me as well.

In terms of journalists and essayists, I have a bunch. I think I really admire and I actually teach often the interviews of the Italian journalist Oriana Falaji she was a very courageous journalist. She’s actually already passed by now, but she interviewed these heads of state and did these incredible things. She interviewed I had Ayatollah Khomeini and took off her veil during the interview. She was a very brave reporter. She was actually quite pro-Israel. She had other political views that were sort of very controversial. But her courage as an interviewer, her ability to ask questions in terrifying situations was amazing to me always. I revere Joan Didion’s prose and her social observations are just so exquisite. And I think today’s writers frequently published writers. I’m a big fan of Taffy Brodesser-Akner, who was a master at profiling

David Bashevkin:

What does she write?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

… New York Times. She’s sort of known for her profiles of celebrities specifically, but she also did come out with a novel “Fleishman Is in Trouble” recently, which I think is now being made into a film. Just something about her creativity with prose, she really pushes boundaries. In a New York Times profile sometimes… I think there was one moment. I think it was in her profile of Gwyneth Paltrow she repeated a sentence. Like she just-

David Bashevkin:

Verbatim.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Yeah. Verbatim repeated a sentence because she just wanted to make that point. And I was like, what?

David Bashevkin:

You’re allowed to do that?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Yeah. Are you allowed to do that? But she does. And she just goes with it and I love that. I love that she breaks the formulas.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. Tell me one more.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

I’m going to give you more than four. Okay, I’ll give you one more Jia Tolentino. She was at The New Yorker. I don’t know what she’s up to now, but she had a collection of essays recently called “Trick Mirror” and I think her essays and describing millennial American culture and this moment in time are just so smart and interesting. I don’t always agree with what she has to say, but the way she writes is so beautiful.

David Bashevkin:

I need to thank you because I sometimes hang out in circles that have allowed me to convince myself that I am well-read and that list has reminded me that I am, in fact, not as lettered as I sometimes convinced myself that I am. That was a really, really extraordinary. Part of what I wanted, and I want to get to this in one moment, it’s the summertime people are relaxing, everybody’s looking for something to read. And I want to hear your examples of literary nonfiction articles or books that I want to get to that in one moment. But I wanted just to return as a final the writing process, I want to return to the social media component and the criticism. You undoubtedly have found yourself centered in different social media criticism, both from within own community, from people adjacent to your community. And it’s something that I think anybody of somewhat notoriety who’s prolific in any way deals with.

And I wanted you to maybe return and tell me more about how do you practice self-care to ensure that criticism online doesn’t metastasize and trickle in to your, not just your home life, but you’re very self-conception, why doesn’t it seem to rattle you in the way that like… For me, if I get just not even nasty, just like some basic negative tweet, I could be knocked out. I have thin skin and I’ve learned to appreciate the fact that I have thin skin. So what do you do to practice self-care, do you have very thick skin? Do you fight back? What is your philosophy of self-care as a writer in the public square, in the Jewish community?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

It’s funny you asked this question because I was literally just thinking about this yesterday. I feel like I blur out a lot of the criticism. As I said to you before, I don’t remember what people say about which article or whatever. And I think that’s part of the coping mechanism. Eleanor Roosevelt said that a woman in the public eye must develop a hide as thick as a rhinoceros. And I feel like life has forced me to do that, even though that’s not my nature. My nature is I like to please people, I like to make people happy. I’m not—

David Bashevkin:

People pleasing. It’s my Achilles heel.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Totally. And it’s really not my nature. I never was. I was always a good girl. I was like the yearbook editor. I was the girl who got the awards, the principal’s favorite. That is my personality, but that doesn’t mean that I don’t want to write and say what I want to be able to say. And I think recently I started realizing literally just yesterday, I was looking through some ad. I remember there was a social media post that someone mentioned to me. And I started remembering how basically, since I’ve been very young have gotten used to people posting terrible things about me publicly and like about me as a person. It’s not like posting a link to an article saying, “Wow, this is a terrible article and I really disagree with it for X, Y, and Z reasons.” Like, no, they will go personal.

And I honestly don’t know how I got through that at that age. Now I feel much more relaxed and comfortable. Not comfortable, we don’t like comfortable in journalism, but I know who I am. And I don’t know how I went through that at that age. And I definitely had hard moments. I will share one story. There was one time that I will never forget. I once tweeted something pretty innocuous saying that young female journalists in Israeli media experience harassment on the job. And that I had experienced that as well, like literally basic vague sort of supporting someone who was talking about this issue at that moment. And I guess the Israeli media was having a slow news day that day because they needed to manufacture something.

So the next day I wake up and my phone is buzzing off the hook. I’m getting messages from all the top Israeli news channels and someone sends me the front cover. I think it was Makor Rishon, one of the Israeli papers, sent which had a photo of me taken of me at a big [inaudible] daughter’s wedding, I think me and my husband were, I think, engaged at the time, with this headline that this religious journalist rabbi’s wife says she too was harassed on the front cover of an Israeli newspaper.

It was a nightmare. I was supporting someone saying that this exists and the entire Israeli media was overwhelmed with this story for some reason in that moment. And I remember it was a Friday morning and then Shabbos day, and we had shul members coming over who were reading Israeli news and they were sort of making comments like,” Avital, what is she doing? What is she saying? She shouldn’t say things like this.” Someone brought a cutout of the actual print paper to my husband’s office to make a point of it. I was overwhelmed by this. How could this have happened? I literally just tweeted something so simple with nothing but it was enough that people wanted to just bite and blow it up.

And Sunday morning I had to attend a luncheon for some event, a function at the St. Regis Hotel. And I’ll never forget, getting dressed and getting to that Uber and just thinking to myself, I need to put on a smile right now. I need to be strong. I know that the entire community’s talking about this, I need to be strong. I need to smile. And I remember getting out on Fifth Avenue and literally the thought running through my mind, if I jump in front of a bus, what’s going to happen. And I don’t think I’ve ever experienced that in my life. I’m a pretty stable person, but it pushed me to my limit and it had a very dangerous effect. It could have a very dangerous effect if one lets it affect you.

The way I deal right now, first of all, I don’t read. I don’t read comments. I don’t engage. I actually told both my parents and then my in-laws, I had to have conversations with them and I told them, I don’t read the comments and neither should you for your own sanity. Some of that takes the time to write a disgusting talk back or post something derogatory on social media. It tells you something about the person if you ask me, right? Again, something personal, not a disagreement with what the person is saying. And that I think it’s telling, and we shouldn’t be busy with that. So, that’s my one rule.

David Bashevkin:

Avital I’m not questioning that you’re not telling the truth. You are really able to not read your comments. You’re going on the record saying that.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

100%, at this point, I do not read responses to my tweets. I don’t have Twitter on my phone. I don’t read my mentions and I literally… But I’ve had to do that in order to protect myself because the last thing I want to do is to read that. And literally I’ve had people… People used to send me screenshots and links, did you see what this person is saying about you and this person? And I have had to go back to these people who are my friends and say, “Listen, thank you so much for being worried about me, but I just don’t need to read that. I don’t need to see that.” Again, people who respect me, who disagree with me, almost always write me an email in which they lay out their points and that it’s a totally different story. But these are character assassinations there is no reason for me to see that.

I think in general, Twitter specifically has had, but this happens on all platforms, but Twitter has really done something terrible to our brains. And I’ve watched many media colleagues, honestly spiral out of control because they’re affected by the algorithm, by the machine, by this the reward for hysterics and for emotion because that’s what gets you attention. And I think I really want to stay away from that as much as I can. Like what I post online is what I really just want to post online. It’s not because of a following and growing my following. Thank God, I’m happy with my following. I don’t need more of it. It’s fine. So that’s number one, it’s trying to shield myself from it.

And the second piece is back to my pin tweet. Really faith helps me. Sometimes it still is hard and I really pray for strength. And I remind myself that I’m trying to follow in the footsteps of a long history of voices who were silenced or harassed for what they did in the Jewish community. I mean, we used to burn books, right? Like this is not a new phenomenon at all. And right now actually the stakes are pretty low compared to what there used to be. And my husband always reminds me the end of Megillat Esther, at the end of the book of Esther, we say “Mordechai ratzui lerov achav,” Mordechai was loved by most of his brothers were in and not all of them. And this is someone who literally just saved the entire Jewish people. You can save the Jewish people from genocide and still not everyone will love you and you have to remember that. That’s just the reality. That’s human nature first of all. And there are other factors as well.

And I know who I am. I know what I stand for. I feel confident at least for this, that I’m following the path that Hashem set out for me. And sometimes I just tell myself, I literally put this as my WhatsApp status this week, vinafshi keefar lekol tihye, that my soul should just be like dust to everything. It shouldn’t bother me. I shouldn’t care. And I say this as a journalist, I say this as a writer, as a rebbetzin to be honest. I feel like I experienced this every single day in different levels and that’s just the only way to get through it.

David Bashevkin:

Not to not be reactive. That is really extraordinary. Let me just give a quick shout out because we haven’t mentioned him by name. Your husband, Benji Goldschmidt, who I also know for quite some time and was in a yeshiva with his brother. We have a lot of intersections, but that obviously is not to go through all of our familial connections would require an entirely different interview. Really what this is about, and I want to get to this I know it’s at the very end, but it’s the summertime, people are looking for things to read. things that are enjoyable, that they can access. Can you give me three examples of literary nonfiction articles and books that you love and why you love them?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Sure. So I think they’re all light enough that you could read them this summer. Though, generally I tend to be a dark reader.

David Bashevkin:

Yeah. I just discovered that when you started reading Tolstoy at 12 years old.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

It affects you. Yeah, I think I would start actually going back to John Didion. I read this essay in college and it’s sort of typical, but I come back to it frequently. It’s called “Goodbye to All That.” And it is a short essay which really captures New York City a place that it is and what it means, especially in youth. She just has this beautiful prose where she can weave in the personalities and the locations and that just the images are so New York. And having lived here for over 10 years, I really feel like that’s one of the best portraits of this city in literature today. Do you want me to read a quote from it?

David Bashevkin:

Yeah, please.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

She writes, “I still believed in possibilities then, still had the sense so peculiar to New York that something extraordinary would happen any minute, any day, any month. You see, I was in a curious position in New York it never occurred to me that I was living a real life there.” She sort of captures this very fleeting city experience.

David Bashevkin:

I love that.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Yeah. And it’s actually describing her leaving New York and she’s reflecting on that. And it’s also just living here and again in a large shool, large synagogue in Manhattan and seeing all the people who come through here. I find that that transitory experience of New York, New York being like no other city in the world is so on point.

David Bashevkin:

Okay. So the first is Joan Didion, “Goodbye to All That.” Give me two more recommendations. What’s your number two recommendation?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

So number two is a long one and I mentioned it already. It is the subject of my thesis, “A Tale of Love and Darkness” by almost Amos Oz, which is a story about the writer’s life growing up at the birth of the State of Israel. It’s also a story of nostalgia and a story of an unrequited love for Europe that many immigrants I think felt in Israel at the time. He starts in the thirties and British Mandate Palestine. And I think generally, it’s a story of immigration and I have obvious reasons for why I related to it my parents are immigrants. But I think it’s actually very timely with the sort of a conversation around Israel right now. He has this one line where he says, “Jews go back to Palestine. The graffiti in 1930s, Lithuania urged his family. So they went then later the walls of Europe, shout ‘Jews get out of Palestine. And I think that really sums up in a very brief way exactly what many Jews feel both in Israel and outside.

David Bashevkin:

And your final recommendation for a summer non-Fiction read.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

This one is a short one. It is an essay in the Paris Review by Sabrina Orah Mark titled “U Break It, We Fix It.” And I think it was in November late last year, she published it. I was amazed that someone could literally write a dvar Torah in the Paris Review where she talks about sort of reflects in the pandemic and this feeling of brokenness. And she relates it to the tablets, the set of 10 commandments that Moses broke. So she says, “In Exodus, the first set of 10 commandments broken by Moses is not buried, but placed in the Aron HaKodesh, the holy Ark beside the new unbroken tablets, which the Jews carry through the wilderness for 40 years. I imagined the broken tablets leaning against the unbroken ones telling them secrets, only broken. I imagine the weight of the broken tablets and the heat and the thirst and the frustration. Why didn’t we just leave the broken tablets behind what good is all this carrying? To know your history is to carry all your pieces whole and shattered through the wilderness and feel their weight.”

David Bashevkin:

Well, “telling them secrets that only broken things know” that is… I remember reading that piece. So I’m one for three in your recommendations. And that was an absolutely a chilling piece, really, really moving. And our listeners should definitely check that out. Remind me what her name is Sabrina?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Orah Mark. Orah O-R-A-H.

David Bashevkin:

Beautiful. Beautiful. Okay. I always wrap up with a little bit of rapid fire questions. I hope that that is okay. My first question is, is there a book again, we’ve recommended a lot of books on subject matter, and we’re not going to get into the nitty gritty of reading books about the act of writing itself. Are there any books about writing itself that you could recommend to our listeners that have inspired your process?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Okay. There is a book by Lisa Krohn. It’s called Story Genius.

David Bashevkin:

Story Genius.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Yes. I think it’s called Story Genius. There’s a subtitle of some sort of Story Genius: How To use Brain Science To something. Basically, it’s a book about what makes a story. And she has another book called Wired for Story, and both of them dive into the psychology behind plots, what makes a plot interesting? Why our brains are wired towards some plots versus others, how to layer a story really well. And it’s largely, I think we’re in for fiction writers and for screenwriters but it helps the journalist as well. Because I, as a journalist, let’s say one of my next stories, I have a whole a wealth of facts, a wealth of information, my ability to build that story well relies on some of this psychology. So I think that’s really important.

And then the other, sorry, I’m going to give you two answers. And the other thing is just to read excellent prose. And one senior journalist told me this years ago is his advice to me, which is to say that even if you want to write academic or journalistic writing it can help to read this great poetry, to read great fiction, something that just read great sentences, read the way that people write eloquently. And that I think has had a huge effect on me I think more than most on writing types of books.

David Bashevkin:

I am of that school, too. It comes from my father’s rebbe when my father was getting into total learning for the first time, he would always say, don’t learn about it, learn it.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Learn it.

David Bashevkin:

Just immersing yourself in that great prose. Avital, if somebody gave you a great deal of money that allowed you to take a sabbatical for as long as you needed to either go back to school and write a PhD, or to write a book. What do you think the title and subject matter of that book or PhD would be?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Oh my God, that’s a tough question. It would definitely be a book. I have no interest in doing a PhD, to be honest. And I would definitely spend that time in Jerusalem. What title? I’m actually very bad at titling.

David Bashevkin:

What subject matter? Meaning what’s the subject matter that you think you would gravitate towards?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

I have answers, but I can’t say them on the spot podcast.

David Bashevkin:

You have answers, but you cannot say them on this podcast. Maybe that is a subject in and of itself. The things that are left unsaid.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Yes.

David Bashevkin:

I will let you off with that as an answer. Your subject matter will be things left unsaid. And then finally, I always ask, because I’m always fascinated by people’s work routines. What time do you go to sleep at night and what time do you wake up in the morning?

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

I recently shifted this considerably. I have never been a late or early person. I just sort of went to bed at 11 and woke up whenever my kids woke me up. Now I go to sleep early. I go to sleep by 10 and I wake up at six.

David Bashevkin:

You go to sleep at 10:00 PM.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Yeah.

David Bashevkin:

Taking Twitter off your phone, it’ll do wonders.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Not always, sometimes I’m up later, but unless I’m hosting.

David Bashevkin:

Unless you’re hosting the hostess.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Yes.

David Bashevkin:

You wear many hats and I am so appreciative and it was such a privilege that you shared so many of them with us today. Avital thank you so much for joining us on 18Forty.

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt:

Thank you so much for having me.

David Bashevkin:

I absolutely loved my conversation with Avital. I find her to be incredibly insightful and more than anything else, incredibly courageous. There is a way that she writes where she weds both her advocacy for the issues that she feels strongly with, but with a prayerful religiosity that I think animates so many of the words that she shares. Of course, I don’t always agree with the positions or the issues that she highlights. I don’t agree with anyone. That’s the beauty of reading and connecting to people. But what I do always agree with a 100% of the time is the conviction and the clarity and the beauty with which Avital shares her ideas. And I can think of no one more qualified to talk about how to share Jewish and religious ideas in print in a prayerful way without kind of sucking away all of the complexity spirituality that informs so much of the transitions and issues and religious communities.

She’s able to wed that journalistic instinct that requires a little of sobriety when you approach those issues with something far more prayerful and spiritual and her ability to integrate those two together is something I have always found nothing short of remarkable. I promise that I would share three recommendations of my own of things that you can find online and print out and read on your own. So, first and foremost, before I get into the three, I just want to recommend to all of our listeners, if you don’t know about this website find it right now. And that is longform.org.

Longform is a colloquial word that’s probably been added to the dictionary now that’s used to describe what I would call narrative non-fiction. Which is non-fiction articles, things that really happened, real people, stories, but it shared not in that very cold, like a textbook, but it’s shared as a narrative. I think the person who really kind of created this genre of writing is most famously Truman Capote with his book in Cold Blood, it’s a little bit of a violent book, but you could definitely read it on a beach, if that’s what excites you. But aside from Truman Capote, this has literally exploded these true-to-life narrative nonfiction, taking a real story, a real incident, but sharing it with the flair, curiosity and storytelling that we normally associate with fiction.

So there are three recommendations. I’m not going to read them for you because they are very long form. These are long articles. Some of them have even been later repurposed into books, but I want three for you because I think they tell really powerful stories about religious life itself and they’re all worth reading. The first story was originally published in The New York Times Magazine, called “Choosing My Religion,” by Stephen J. Dubner was published in March 31st, 1996 and was later published as a book. You can find the entire article online and I found it absolutely moving the way he talks about his navigation with Jewish life, with religious life, it is absolutely worth reading.

And I’m good read with each of these articles what I find to be just a really beautiful highlight for each of them. And this is what Stephen J. Dubner writes in “Choosing My Religion”: The rabbi, a soft voice, sad-eyed old man turned out to be the boy’s grandfather. He stepped forward to give a sermon during these of reflection he said he had been asking himself what makes us keep on being Jews when it’s such a struggle? And I found the answer in six words. He said six words in the Talmud written by Rashi. He will not let us go. It isn’t a matter of choosing whether to quit God, the old rabbi explained it is God who chooses not to quit us.” And I found that passage to be so moving and so powerful in his journey. And I absolutely loved it. And he’s one of the most fantastic storyteller. Stephen J. Dubner what he does in Freakonomics. I’m sure you’ve heard here there’s books. There’s podcasts. He’s unbelievable.

Another reason why I’m sharing this with you now, that story that he has from his rabbi, six words in the Talmud written by Rashi, “he will not let us go,” is that I have no idea where this Rashi the great commentary on Talmud where this Rashi even is. And I did email Stephen J. Dubner a while back to find out and he was kind enough to respond, but even he didn’t remember. So if there are any listeners who remember six words in the Talmud written by Rashi, “he will not let us go.” What on earth could this be referring to? I have a couple guesses, but if anybody knows, I would very much appreciate it you reaching out.

There is a second article which I also found absolutely wonderful. And that is an article that appeared in Rolling Stone Magazine. Yes, you heard correctly Rolling Stone Magazine. And it was published in April 21st of 1977. So you have to go a ways back. And the article is by Ellen Willis and it’s called “Next Year in Jerusalem.” And the subheading is of when her brother embraced Orthodox Judaism, the author began to question her own reality and went to Israel to find some answers. Now you may not appreciate the journey that it goes on or where it ends, but if you appreciate how I need how to enjoy a story, and it doesn’t really matter how it ends or what you went through. It’s just a phenomenal story where she goes to Israel after her brother enrolls in Aish HaTorah, the Yeshiva that still exists now, right outside of the Kotel walls.

And her journey to Israel and contending with religious ideas. And she met with at the time, the leader of Aish HaTorah and the fact that this story appeared in Rolling Stone Magazine, which has not in my and I was never a subscriber, but I certainly don’t associate Rolling Stone Magazine with stories about to yeshiva and return, but she did an absolutely a phenomenal job I thought in this article depicting what religious doubt contention journeying is all about, which is why I am so excited to recommend this article for you again next year in Jerusalem. And you can find it on rollingstone.com.

I’ll read just a quick passage towards the end. No spoilers. You can close your ears if you don’t want to know just has a little bit oof a foreshadowing of what happens, but she writes, “Mike,” meaning her brother, “had been 24 when he became religious. I had been 23 when I came out of my deadly depression. It seemed to me that both changes represented the same basic decision to be happy, but mine had been purely intuitive decision to allow myself to feel. His had presented itself as an intellectual decision to go where his logic led. Perhaps our paths were equally valid, perhaps not. As I kissed my brother goodbye, I still did not know whether my refusal to believe was healthy self-assertion or stubborn egotism. The Jews, the Bible tells us, are a stiff neck people.” I think that this is a beautiful paragraph and a beautiful story about siblings journeying trying to find and make that decision to be happy. What’s necessary? Your heart, your mind, you work with both. It’s a brilliant story that appeared in Rolling Stone Magazine. And I don’t know if any of our listeners know what became of her. I would be so happy to hear or to know, find out more, but Ellen Willis, a really brilliant writer and an incredible story that is worth reading and relaxing enough and interesting enough that you can get through the whole thing on the beach.

The final story is not as focused specifically on the Orthodox community or even the Jewish community. It’s about a religious community and a religious sect, and somebody leaving this sect and developing a healthier relationship with themselves and religious ideas. I remember reading this article in one sitting, I could not put it down. And the title of the article is “Unfollow” by Adrian Chen. And it appeared in The New Yorker in November 15th, 2015. And it is the story of how one of the daughters of the Westboro Baptist Church, which is one of the most inflammatory religious sex that has ever been out there. They’re the ones who have those very ugly signs and protests outside of funerals.

I don’t want to go into to it more you can read the article to find that more, but what is really incredible is how one member of this church began to question their own religious commitments and ended up leaving the church and how they left and fostered a healthy with religious communities, with Jewish communities, I think is an incredibly moving story of how religious communities can sometimes suffocate, but other times empower and breathe life into somebody’s discovery of sense of self. And what I found so powerful about this article is that it really tells both of these stories and people have experienced both even within one lifetime.

What’s also kind of remarkable and really uplifting is that much of her journey is facilitated through the Jewish community, the very community that she one time protested against and blamed against for all of these apocalyptic theological reasons. She ends up coming back and really embracing a healthier sense of self through her connections to the Jewish community. So it’s a story of modernity. It’s a story of growth. It’s a story of religious growth. And it’s the story of how boundaries of religious communities, particularly in the age of social media and online engagement have really shifted in a lot of ways that you could tell the story also from within the Orthodox community. I’m obviously not God forbid making any comparisons in the Orthodox community and the Westboro Baptist Church.

I mean, these are not good people and that’s really, really clear, but the idea of questioning and figuring out your place within community has definitely been challenged, not in a bad way, not a bad challenge in a healthy challenge because of the way that we interact and see so many other ways of living in so many other community. That’s part of the challenge, crisis, excitement, freedom, opportunity of modernity that we cover so much in 1840. So again, the three article recommendations find a good printer where you can print these out, read them on a beach, “Choosing My Religion” by Stephen J. Dubner that appeared in The New York Times Magazine. Ellen Willis’s article “Next Year in Jerusalem” from Rolling Stone Magazine and finally “Unfollow,” by Adrian Chen that appeared in The New Yorker.

Thank you so much for listening. And I’ve been getting a lot of feedback about my closing and I’m thinking of revamping it. I usually say it wouldn’t be a Jewish podcast without a little bit of sharing, but people have been trickling in and telling me that is playing into Jewish stereotypes. So even though I obviously meant it in a playful way, people have asked me to find a new way to wrap up your episodes and I am in the process of doing so. But in the meantime, if you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe, rate, review, tell your friends about it. It really helps us reach new listeners and continue putting out great content. If you’d like to learn more about this topic or any of the other great ones we’ve covered, be shorter checkout 18forty.org. That’s the number one eight followed by the word forty F-O-R-T-Y.org, 18forty.org. You’ll also find videos, articles, and recommended readings. Thank you so much for listening and stay curious my friends.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Hadas Hershkovitz: On Loss: A Husband, Father, Soldier

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Hadas Hershkovitz, whose husband, Yossi, was killed while serving on reserve duty in Gaza in 2023—about the Jewish People’s loss of this beloved spouse, father, high-school principal, and soldier.

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Elissa Felder & Sonia Hoffman: How the Jewish Burial Society Cares for the Dead

Elissa Felder and Sonia Hoffman serve on a chevra kadisha and teach us about confronting death.

podcast

How Different Jewish Communities Date

On this episode of 18Forty, we explore the world of Jewish dating.

podcast

Red Flags: A Conversation with Shalom Task Force Featuring Esther Williams and Shana Frydman

We have a deeply moving conversation on the topic of red flags in relationships.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Shlomo Brody & Beth Popp: Demystifying Death and the End of Life

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Shlomo Brody and Dr. Beth Popp.

podcast

‘Everything About Her Was Worth It’: The Life of Yakira Leeba Schwartz A”H

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Yisroel Besser, who authored many rabbinic biographies and brought David Bashevkin to Mishpacha magazine, about sharing Jewish stories.

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Benny Morris: ‘We should have taken Rafah at the start’

Leading Israeli historian Benny Morris answers 18 questions on Israel, including Gaza, Palestinian-Israeli peace prospects, morality, and so much more.

podcast

Rabbi Meir Triebitz: How Should We Approach the Science of the Torah?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down with Rabbi Meir Triebitz – Rosh Yeshiva, PhD, and expert on matters of science and the Torah – to discuss what kind of science we can learn from the Torah.

podcast

Anshel Pfeffer: ‘The idea that you’ll obliterate Hamas is as realistic as wanting to obliterate Chabad’