What Shabbos Means to Me

I am only 36 years old, but I have already experienced three very…

What is Shabbos? In some ways, the bones of the day of rest are identical for many: rest, resisting the urge for work and technology, and an increased focus on the important parts of life. In other ways, each Shabbos has its own timbre, buzzing along to the vibration of its own string, different and…

Rabbi Yohanan said in the name of Rabbi Shimon ben Yohai: If only…

He who binds to himself a joy, does the winged life destroy. He…

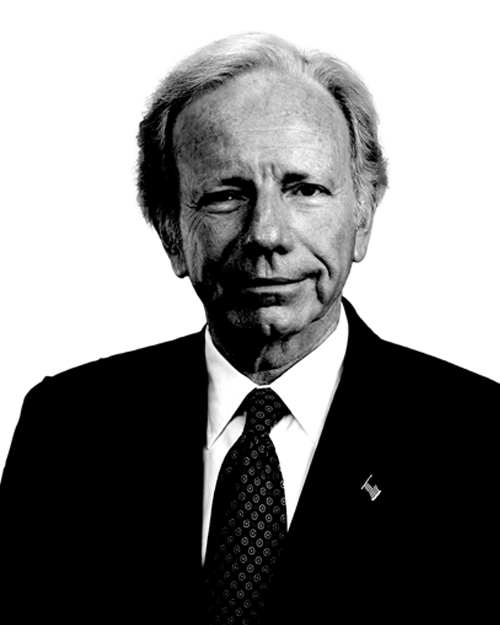

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Senator Joe Lieberman – politician, lobbyist, and attorney – about the gift of Shabbos.

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Senator Joe Lieberman – politician, lobbyist, and attorney…

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to author and journalist Judith Shulevitz about the world…

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk about two impactful books about Shabbos and their authors.

What the temple was in space, Rabbi Heschel teaches us, the Shabbos is in time, a temporal sanctuary, and what the Shabbos is in time, The Sabbath is in text. A timeless classic beloved by many, this book does not just speak about the power and poetry of Shabbos, but it somehow seems to speak in the very language of Shabbos itself. Heschel’s unique capability, creativity, and artistry as a writer and thinker come through in this short, poignant text, and it makes for the perfect read to appreciate what Shabbos has to offer all of us, in our own ways.

In a world in which our eyes are constantly pulled towards one screen or another, it so often feels like we have no better option than to hunt for better websites, articles, and movies. But how can we free ourselves from the constant pressures of our work life, of the life of the six days of creation, in favor of a more balanced, peaceful life, a life that honors the Shabbos on each day of the week? Odell’s work seeks to answer this question, as she urges us to save our own attention and our eyes from the screens around us, in favor of more healthy and holy forms of attention. Agree or disagree with her assumptions or conclusions, Odell offers an important set of suggestions for how we can escape a world in which powers stronger than us are…

While Shabbos for some is a day of rest and relaxation, other people have a more complicated relationship with the day of peace. Whether it’s the labyrinth of laws that surrounds the holy day or the emotional associations of the day, the day of Shabbos is a complex day for many, and Shulevitz enters the totality of the Shabbos story with depth, honesty, and intellect. In her book, Shulevitz moves from the ancient to the modern with ease, weaving her own memories and thinking with sources about the history of Shabbos, pulling together an ultimately redeeming narrative of one person’s loving struggle with Shabbos.

This is your address for today’s biggest Jewish questions. Looking for something in specific? Search on our homepage or browse on your own.