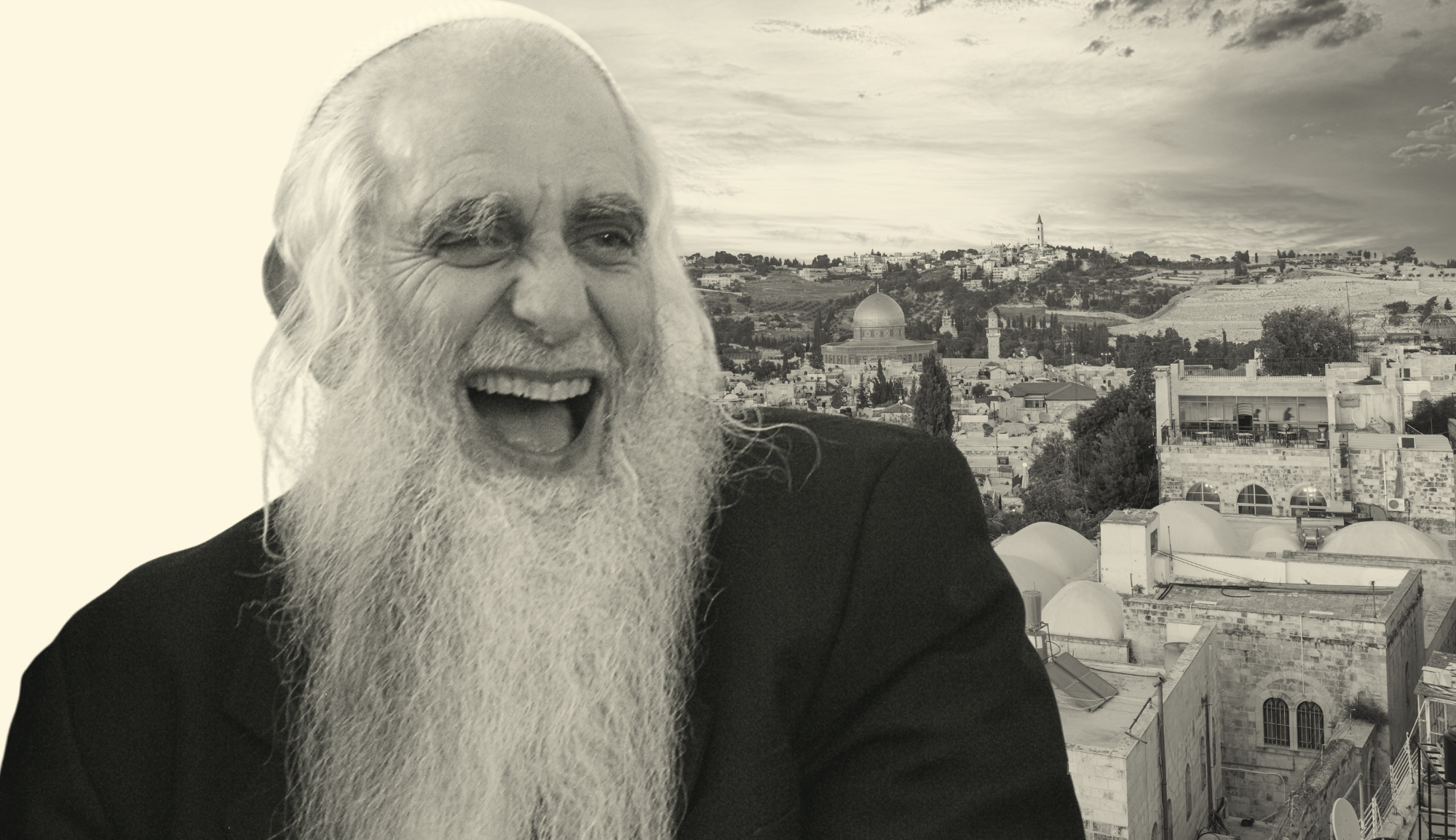

I’m a hardcore advocate that anything can be translated. After all, I translate poetry, personal prayers, and even songs. Yet, I hesitated when I was asked to translate the teachings of Rav Menachem Froman z’’l—the rabbi, peace seeker, and spiritual leader who defied all boxes and expectations.

I asked myself: Will anyone be able to understand Rav Froman? In English? Will what he has to say make any sense to those whose feet do not walk the stones and earth of Israel? Who do not dream Hebrew dreams? Rav Froman was not simply Israeli, but eretz Yisraeli—someone intrinsically bound to the Land of Israel and to the Hebrew language in which he taught, composed poetry, penned arguments, and spoke.

Any translation requires one to translate not only the literal words but the spirit behind them. Behind any text—not only the Torah—lies the white space, the intent and spirit of what was said. Rav Froman was all at once a devout believer, an iconoclast, a peace-seeker, a settler—even the rabbi of a settlement—it seemed to me that the task of being faithful to his words, but more so the layers of his intent, would be almost impossible.

Rav Froman’s voice, with his emphasis on bringing together opposing sides that seem can never meet, is so fitting for now, and I would argue so critical, that it is worth the risk to have done so.

The newly released translation of Chasidim Just Laugh—Hasidim Tsochekim Mize, in Hebrew—is a collection of short ideas and stories plucked from classes and lectures Rav Froman gave over many years. In the introduction, his eldest son, Yossi, the book’s editor, acknowledges that his father would most likely not look favorably on what he’s done, pulling just these sections out of their context. This means that even in the original Hebrew version of the book there was a concern of something being lost—how much more so in a foreign language? Maybe that is inevitable, and some would argue that if so, it’s not right to translate. But Rav Froman’s voice, with his emphasis on bringing together opposing sides that seem can never meet, is so fitting for now, and I would argue so critical, that it is worth the risk to have done so.

And it is worth the effort to read his words, even if they make one uncomfortable—which they very well might. He wasn’t politically correct. He didn’t sugarcoat anything. He spoke from his heart. And he had an exceptional love for his family, his people, and all people. His voice is one we need to hear.

A Sense of Rav Froman

To get just a slight sense of Rav Froman, I begin with three stories.

I first “met” Rav Froman when my husband and I attended a roundtable discussion where he spoke, along with three or four others, about the teachings of Rebbe Nachman. I don’t recall what he said, probably because it wasn’t his words that moved me that evening; it was what I witnessed.

In the middle of the evening, Rav Froman’s eldest son walked into the room. Yossi (years later I learned his name) looked to be about 25—tall, lanky, wearing Bohemian-style clothing, donning long peot, or sidecurls. He sat down next to his father and I watched as Rav Froman gently stroked his grown son’s peot. I had never witnessed such an intimate moment between a father and his adult child. Watching it made me cry.

Many years later, after the rav’s passing, I told this story to Yossi, now married and a father himself. This time, he cried.

The next time I met Rav Froman, I actually did speak to him for a moment. We were at a “Sulcha” gathering, a peace festival that used to take place each summer. It was the first I’d ever gone to, and though maybe I attended one more time, I never became a regular. But Rav Froman most definitely was, and the largely secular and hippie crowd loved him.

It was between workshops when Rav Froman spotted me pushing my toddler in a stroller while wearing my baby in a carrier. He began telling me about his daughter, the eldest of his 10 children, who recently gave birth to her second child. He was enraptured with babies.

Finally, another story—this one told to me by Shlomo Spivack, a family friend and a close student of Rav Froman’s, who today is behind all of the Hebrew publications of Rav Froman’s teachings. Amongst many stories he told of Rav Froman’s painstaking care to express gratitude to anyone who helped him in any way. For example, when he was hospitalized due to the illness that took his life, Rav Froman not only repeatedly thanked the doctors and nurses, but also made a specific effort to, again and again, thank the hospital’s cleaning staff, because “without them there’d be no hospital”. Shlomo recounted a conversation he had with Rav Froman in his final days in which he implored Shlomo over and over to tell Shlomo’s wife—in his name—thank you. “Thank you for everything she does, thank you for caring for him… thank you, thank you.”

Why do I begin with these stories? Because I want you to understand just how real Rav Froman’s ahavat habriot, his love of people, was. Anyone who knew him has such stories, and everyone who knew him, loved him. Even those who disagreed fiercely with him (and there were many of those) loved him, because there was something pure in his intentions, and in the love he expressed.

Yet, there was also something awkward, uncomfortable, and even disquieting about Rav Froman, and this, too, found plentiful expression.

The art of translating demands “carrying over” the intent behind the words, not just their literal meaning.

Like how at every wedding ceremony he officiated he’d have the groom say to his bride what he explained as the Zohar’s language for marital vows: “Next to you all other women are as monkeys to a human being.” The guests were most often left puzzled, and I heard of at least one bride who refused to let her groom say this.

Or once, at an enlistment party for students of the Tekoa yeshiva where Rav Froman taught, everyone was blessing the soon-to-be-enlisted soldiers that they should return b’shalom, they should come home safely. The Rav, at his turn, said to them: “I don’t bless you to come home b’shalom. If you want to come home b’shalom, don’t go to the army.” The students, bewildered, demanded, “Well, what do you bless us then?” The Rav replied without hesitation: “That you should kill terrorists.”

If you’re beginning to squirm inside, you wouldn’t be the first to be made uncomfortable.

There were so many layers behind everything he said, and it all defied anything at all expected or normal. Rav Froman did not fit into any “box.” He could offend anyone, be endeared by anyone—sometimes at the same time— and could always leave one wondering: Really?

So this proved challenging when translating Rav Froman’s words into English, as the art of translating demands “carrying over” the intent behind the words, not just their literal meaning. With Rav Froman, this was especially so. Consider these passages from Chasidim Just Laugh.

In the first, perhaps he is speaking about himself:

What is the worst thing you can say about a Jew in the religious community? “He’s controversial.” In the religious world, this is terrible. A rabbi who is controversial is worse than a rabbi who is a thief. In contrast, in the secular community, the worst thing is to have exactly the same dress as everyone else. The most important thing is to be different, for there to be controversy. This basically sums up the difference between the religious and secular communities.

Or this, combining the three topics he spoke of most frequently—religion and freedom, peace, and marriage:

People can’t grasp the idea that a call to freedom can be a religious matter. Although our Sages teach that “No one is truly free save for the one who engages in Torah,” [M Avot 6:11] most religious Jews were taught to give up their freedom for the sake of religion.

We see this in many realms. For example, in the political sphere: Most settlers think that the settlements interfere with peace, but they prefer the settlements to peace. They are incapable of believing that the settlements can be for the sake of peace.

Likewise, between man and woman—people think that being free means being single, that getting married means giving up on your freedom for the sake of a wife, marriage, children, a home, etc.

But for me, freedom is the essence of being religious, and my wife is my freedom. It’s like the song: “With you I know, that only with you am I free.”

The settlements are the fingers of the hand extended in peace, and are safeguarding the peace.

So too the settlements are placed in the heart of the Palestinian community.

And this:

I pray that God will turn all the radical Islamic countries from darkness into light. The symbol of Islam is the moon. The moon is a crescent moon, sharp like a fingernail, or like a knife. However, the whole essence of the moon is to transform emptiness into fullness, darkness into light. Islam’s moon could still appear in its fullness. With God’s help, everything can turn around! Many things could happen.

(A bit of insider information I have permission to share with you: Rav Froman actually didn’t say the word “radical.” The book’s English editors were worried that without it, the passage would not be palatable for an international audience. I applaud their courage to include the passage at all, for Rav Froman was not, by any means, Islamophobic as current discourse might label him if one were to read just this. He loved Islam’s emphasis on “nullification,” and would admonish Muslim leaders for abandoning that for extremist ideology. He respected Arabs in a way most Israelis, forget Westerners, never could, for they rarely got to know Muslims. Yet he wasn’t afraid to critique.)

As we say today, it’s complicated—as were many things with Rav Froman.

Rav Froman’s Words Today

Rav Froman passed away over 11 years ago, so the teachings brought in Chasidim Just Laugh precede that. The Hebrew book was published eight years ago, and the English translation was completed more than three years ago. But providence determines that it is being published only now, over a year after October 7, with the people of Israel involved in the most long-lasting and complex battle on the front, and the most long-lasting and complex battle from within.

What would Rav Froman say now?

As I thought about writing this essay, I opened Chasidim Just Laugh to a random page and I read these words:

The greatness of a righteous person is in his ability to be silent. This is greatness. Not everyone knows how to be quiet. Not everyone knows how to say “I don’t know.”

People usually want to hold onto something, to stake out a specific opinion, a position. When I say, “I don’t know, I don’t know”—I live in the reality of “we do not know what to do.” [Chr. II 20:12] This creates an opening for the remainder of the verse: “… but our eyes are on you.” Then I wait to hear the word of God…

The Kotzker Rebbe said, “Where is God? Wherever you let Him in.” When I truly feel that I do not know—I let God in. The silence is the opening.

In another passage, addressing a question I believe most have us have asked in a much more desperate way this past year:

Regarding the most essential of questions, we must be silent. The most difficult theological question is “How is God the source of evil?”; “If God is good, how can death exist?! How can suffering exist?! How?!” What is the answer to this? Rebbe Nachman says that when faced with questions like these, we must be silent.

Rav Froman had a lot to say; he taught and spoke frequently. The vignettes in Chasidim Just Laugh are tiny gems pulled from classes that could easily have lasted two hours. Yet, he was always ready to see a different perspective with a kind of pure, childlike quality he had, alongside deep, deep faith. He didn’t hesitate to say what he had to say, even when it meant people scoffed at or berated him—but he was always ready to say he didn’t know.

In a time of agonizing discourse here in Israel, I yearn for Rav Froman’s voice. What would he say now? About how to bring the hostages home? About drafting Haredim? What would he—the rav who would stand on stage before audiences of religious and secular, Jews and Arabs, settlers and leftists, and have everyone clap, bringing together in a most tactile way opposing sides—do now to help bridge what feels to be an almost abysmal chasm within Israeli society?

I believe that he would likely express strong opinions, and that he’d also be ready to say “I don’t know.”

He would most certainly make space for G-d.

I’ll bring here one final idea without a real introduction, because it’s an idea I don’t really understand, but feel is essential to understanding Rav Froman’s essence, and complexity:

Disregarding reality is essential for the believer. It is the believer’s greatness and weakness. A believing Jew can say not only that “it won’t ever be” but also that “it never was.” Belief isn’t realistic, or, as I like to put it, belief doesn’t see the word of God. It rebels against God, for the entirety of reality is the word of God…

…before the evacuation of Gush Katif in 2005, during Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza. I was in the town of Bedolah the night before they came to evacuate it. I spoke there and I said that even if the town is evacuated, our struggle had not been in vain. One of the residents burst out at me and said, “You came here all the way from Tekoa just to tell us that they’re going to evacuate us?” Perhaps if I had had the same degree of faith as that Jew from Bedolah, a miracle would have occurred, and the evacuation would not have taken place. On the other hand, this could be the ultimate heresy, because ignoring reality means ignoring the word of God…Faith can be freedom from subjugation to facts, without being blind toward reality, and the voice of God within it. This distinction is razor thin.

Does he sound complicated? He was. And so bringing his words to a larger audience wasn’t simple in their original language, much less so in a foreign one. Yet, as I said, Rav Froman had a childlike quality about him, and he yearned for simplicity. About that, he had much to say as well:

There’s a story that I love: Once, a simple woman was seen reciting the liturgical poems of Selichot [Jewish penitential prayers] with great kavanah [intention]. Now, these are poems that even very learned people struggle to understand. They asked her, “Do you understand what you are saying?” She answered, “Of course I understand! What’s written here is a prayer that my son should return home safely…

Rav Froman’s is a rare voice. A voice that is hard to understand, difficult to carry over, and will likely make everyone uncomfortable at some point. But his voice comes from a deep place of faith—in humanity, in G-d, and because shalom is one of G-d’s names, in peace. This makes him a voice ahead of his time, and a voice we need now. Why G-d took him away before this period, I don’t know.

But maybe it is so that we can, collectively, begin to acknowledge how little we know, and from that space, to make space for G-d, and for each other.

Leah Hartman translated the forthcoming teachings of Rav Menachem Froman, Chasidim Just Laugh. She also translated the National Jewish Book Award finalist Prepare My Prayer: Recipes to Awaken the Soul by Rabbi Dov Singer. Leah regularly brings the most meaningful and hopeful voices and music of Israel accessible to the English-speaking world through her digital Substack publication, Translating Israel: One Voice at a Time. Originally from Chicago and Colorado, Leah lives with her family just north of Jerusalem.