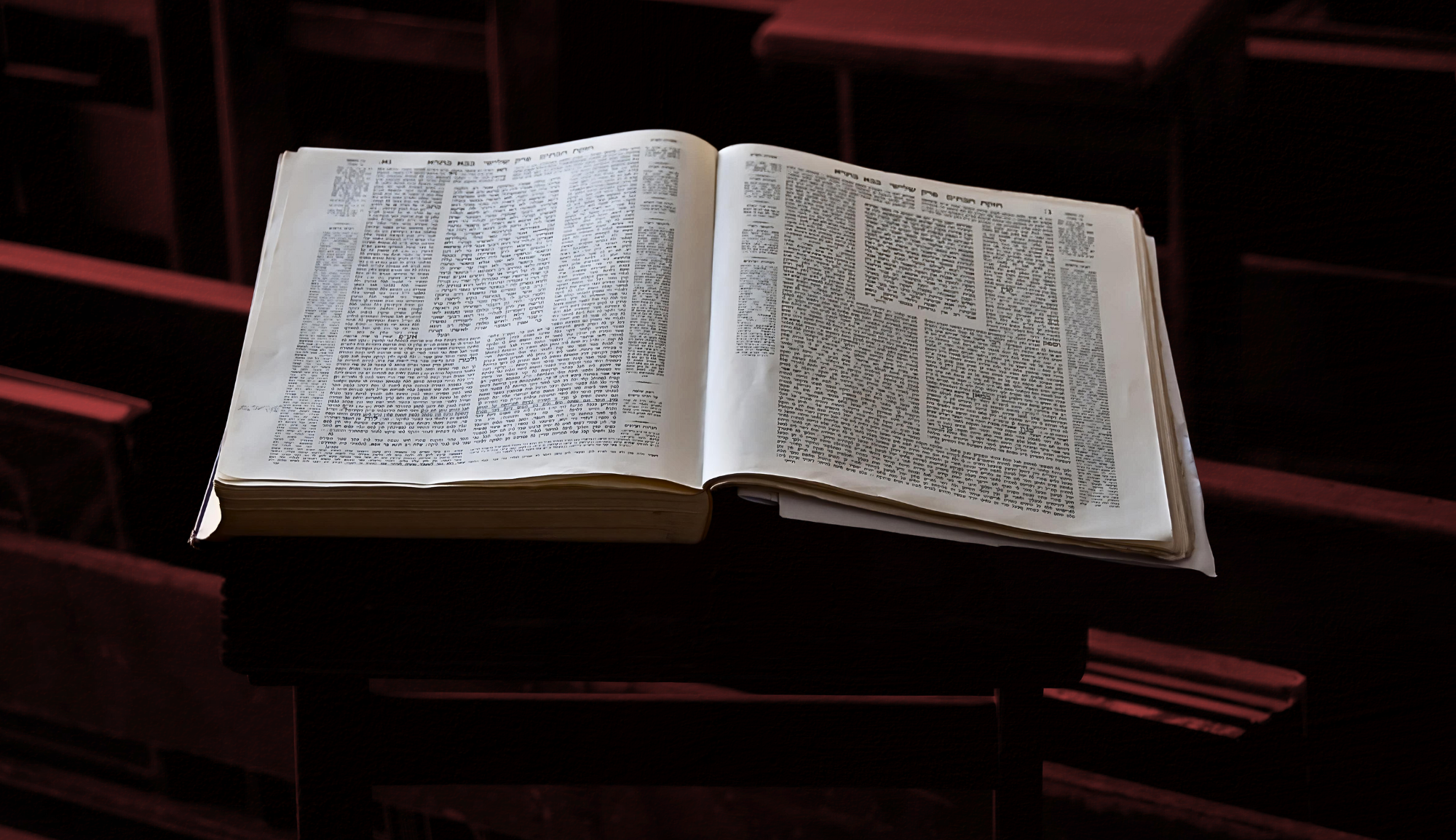

Explaining any element of Jewish law to someone else can be difficult. I’m not sure what’s the most difficult practice to translate and present. I certainly don’t envy anyone who has to explain Sukkot to a colleague. But more than any specific Jewish law, the concept of law itself in Judaism can be deceivingly difficult to transmit. In Hebrew, Jewish law is called Halacha, which derives from the Hebrew word to walk (הולך holeich). Colloquially we may say “Jewish law,” but the actual Hebrew word means something closer to “travels.” A lot of misconceptions derive from this. Most look at Talmud as a collection of Jewish laws—“oh, so this is your constitution.” But that is far from correct. The structure of the process of Jewish law differs greatly from its secular counterparts.

Lawyers are serious; storytelling is for children. The Talmud rejects this mutually exclusive binary.

In fact, instead of using American law to understand Talmud, some have suggested that Talmud should be used as a paradigm for American law. In 1983, Robert Cover opened Harvard Law Review with a now famous article called “Nomos and Narrative.” Most law review articles can be dense and hard to decipher—this is worse. Cover presents the introduction of Rabbi Yosef Karo to Choshen Mishpat, the collection of Jewish civil law, as a model for how to preserve a legal society. He writes, “No set of legal institutions or prescriptions exists apart from the narratives that locate it and give it meaning. For every constitution there is an epic, for each decalogue a scripture.” In Cover’s view, Judaism was able to create a legal society because its laws (nomos) and narrative were integrated. This can be seen on nearly any page of Talmud. In the Talmud, the laws (Halacha) and stories (Aggadah) are interwoven. In Samuel Levine’s brilliant collection, Jewish Law and American Law: A Comparative Study, he has an essay applying Cover more directly to Talmud. There, he cites Hayim Nahman Bialik’s essay “Halachah and Aggadah,” “Halachah and Aggadah are two things which are really one, two sides of a single shield.”

A while back I wrote an essay called The Forgotten Talmud: On Teaching Aggadah in High Schools. It always bothered me that when I was in school we would skip the story passages. There was a feeling that serious Talmud study was specifically associated with the legal passages. In many ways, I think that is a reflection of a general societal reflection. Lawyers are serious; storytelling is for children. The Talmud rejects this mutually exclusive binary. In order to preserve a society, you need both. Without laws, society would not cohere unless that all simultaneously felt mutually inspired—a nearly impossible occurrence. Without Aggadah, society would simply become rote and legalistic. A religious society needs both. Robert Cover suggests that secular society would benefit from integrating both as well.

In 2018 my friend and legal scholar, Chaim Saiman, wrote a brilliant book entitled Halakhah: The Rabbinic Idea of Law. He challenges a lot of the misconceptions about what Jewish law is—and is not. He has always been a bit of an eccentric thinker. He has applied economic theories to describe models of Jewish leadership. He presented the obscure Talmudic world of Brisk in a Law Review article. He is also a friend and someone I’ve gotten lost in conversation with more than once. I tried to stay on topic here—it was a struggle.

We discuss my hometown shul, Christian polemics against Jewish law, the nature of Jewish law and, of course, the Talmud.

Listen to our episode with Chaim Saiman.