To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

We often think of the esoteric as a highly individualized path, far from the community. This experience is certainly well-founded in the textual histories of mystical Judaism. The books of Tanach are replete with such private revelations, mystical experiences that occur in the quiet of deserts and mountains to the many solitary shepherds that comprised the early Jewish leaders.

However, mysticism as a formal pursuit often was built upon community, and the communal component was often a foundational principle and guiding light to mystical journeying.

This idea goes back as far as the second century when Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, protagonist of the Zohar, is accompanied by a loving and closely attached fraternity of friends, the original Chevrayah Kadisha, as it is termed in the Zohar. Life and lessons in the Zohar occurs within the framework of the loving companions of the Chevrayah, who are bound together by their shared goal of transcendence.

William Blake struck on the relationship that community and mysticism can have when he said something like this:

I sought my God,

my God I could not see

I sought my soul

My soul eluded me

I sought my brother

And found all three

God, my soul, and thee.

To better appreciate the complicated relationship between mysticism and the community, we put together a history of the mystical community, from antiquity until today.

We might echo the dictum: Seek not the ancients, but seek what the ancients sought.

Biblical Era: The Age of Prophecy

In the Biblical Era, we find prophetic revelations occurring to individuals and masses, from the private revelations of the fore-parents to the mass revelations at the Yam Suf and Sinai. Many commentators see the public revelations as foretelling of the Messianic era, when revelation will be available for mass consumption, “like water covers the bed of the sea.” The prophetic literature is replete with mystical visions, and we are told as well of the בני נביאים, literally ‘children of prophets,’ or student prophets, mystical communities working towards revelation.

Post-Biblical Era: 1st-7th centuries

In the aftermath of the Biblical world, the mystical world opened up. Rabbinic literature gave cryptic reference to mystical ideas, such as mentioning “the account of the Chariot” (Hagiga 2:1), the tale of the four that entered the ‘pardes,’ or of the magical acts accomplished by sages studying the Sefer HaYetzirah (Sanhedrin 65). The Zohar, featuring Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, is set in this time, and offers commentary on the Torah that is poetic, powerful, and is both highly allusive and elusive. The Heichalot and Merkavah literature, which describe the chambers that surround the Divine Throne and the angels that guard them, also emerged from this era. While far less popular than the Zohar, they are important early works of Jewish mysticism. The Shiur Komah, a highly unusual text that describes or associates the form of God’s glory with different parts of a supernal body, also emerged from this time.

Medieval Mysticism: 12th-13th Centuries

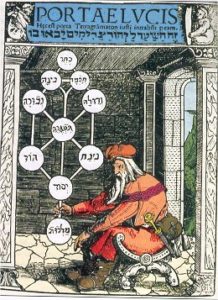

The 12th and 13th centuries were highly important times for the history of Kabbalah. Small groups of highly influential esotericists (appreciate and use this word, please!) raised the profile of mystical texts to the national stage. A tense relationship between Maimonidean rationalism and mysticism develops in this era, prompting the growth of each field. The ascetic pietists of Germany, known as the Chassidei Ashkenaz, are active in this time, with important figures such as Rav Yehuda HaChassid, Rav Shmuel HaChassid, and Eleazer ben Yehuda of Wormz. Groups of Kabbalists in Castille and Gerona were particularly active at this time, with figures such as Raavad and his son, Rav Yitzchak Saginahor (Isaac the Blind, possibly portrayed in the above image). Most importantly to this era is the emergence of the Zohar. Revealed (or something) by Rav Moshe de Leon, the Zohar becomes the fundamental book of Jewish mysticism for centuries to come.

From Safed to Shabtai Tzvi: 14th-17th Centuries

In the wake of the expulsion of the Jews from Spanish countries, the Arizal moves to the heaven-soaked city of Safed (pictured above by the author of this timeline), and with a group of his followers, teachers, and friends, drastically reconstitutes the landscape of mystical Jewish thought. With his focus on Tzimtzum, God’s self-contraction, the Arizal and his students forged a new path in Jewish mysticism. Although he died young, ‘Lurianic’ Kabbalah spread throughout the Jewish world, largely due to the writings of his student R. Chaim Vital. As Spain was a hotspot of Jewish mystical study, the expulsion of Jews resulted in the study of mysticism spreading throughout the Spanish diaspora. By the 17th century, Kabbalah is widely spread throughout the Jewish world when the charismatic Shabtai Tzvi launches a messianic campaign that culminates in his apostasy, shaking the religious world deeply and resulting in deep tension around mystical study. Fears around mysticism linger, later leading to controversy around the Ramchal in Venice and Amsterdam after his own mystical devotions came to light in the mid-18th century.

Revolutions: 18th-20th Centuries

Still shaking from the Sabbatian controversy and the Chmielnicki uprising, the study of Kabbalah is located centrally within small, exclusive groups, such as in Broide, the Bet El Yeshiva in Jerusalem, and around the Vilna Gaon. Kabbalah occupies an important role in the Sephardic communities in Aleppo, Yemen, and Kurdistan at this time, with figures such as R. Shalom Shabazi. Such was the landscape until the mid-18th century, when a humble clay-digger and schoolteacher named Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov launched the Chassidic revolution (his synagogue, in Mezhbyzh, is above). Although he left no written works, his students promulgated his revolution in religious belief and practice, and his emphasis on God, religious passion, and popular mysticism spread rapidly throughout Europe. This movement brought mystical ideas to the mainstream, illuminating popular Jewish thought and action by esoteric thought.

Mysticism Today: 20th-21st Centuries

As the contemporary era awakens, Chassidus has long familiarized vast segments of the population with mystical texts, and translations of the Zohar into Hebrew (first by the Baal HaSulam, R. Yehuda Ashlag) and English find large audiences. Several independent waves of Neo-Hasidic movements occur, each raising the relevance of mysticism for modernity. Hillel Zeitlin’s stirring call for a new mystical community marks the first wave of such movements, followed by the Aquarian era neo-Hasidic movement in post-War America helmed by Reb Zalman Schachter Shalomi and Shlomo Carlebach. In the early years of the 21st century, the Orthodox community has seen its own kindling of interest in Chassidic and mystical thought, due in large part to the leadership of Rav Moshe Weinberger and his students. Mysticism and spirituality have experienced a far reaching growth in popularity on both sides of the Atlantic, but the religious culture in Israel has brought a particular efflorescence to Jewish mysticism (as the above work by Israeli artist Arik Weiss demonstrates).

So here we are today. From then until now, mystical study and community has taken many forms within Judaism. Some argue that there is no Jewish mysticism, that the very word ‘mysticism’ is of foreign extract to the ways Jews approach the mystical. Others might argue that there is no one ‘Jewish mysticism,’ but rather a large swathe of approaches and perspectives, taken in widely varying contexts over history. In any case, we look at this short history as an invitation for study, not a conclusion to study. We might echo the dictum: Seek not the ancients, but seek what the ancients sought. Seek what the ancients sought, and how the ancients sought it, and we might hope to learn more about the mysteries of mysticism.