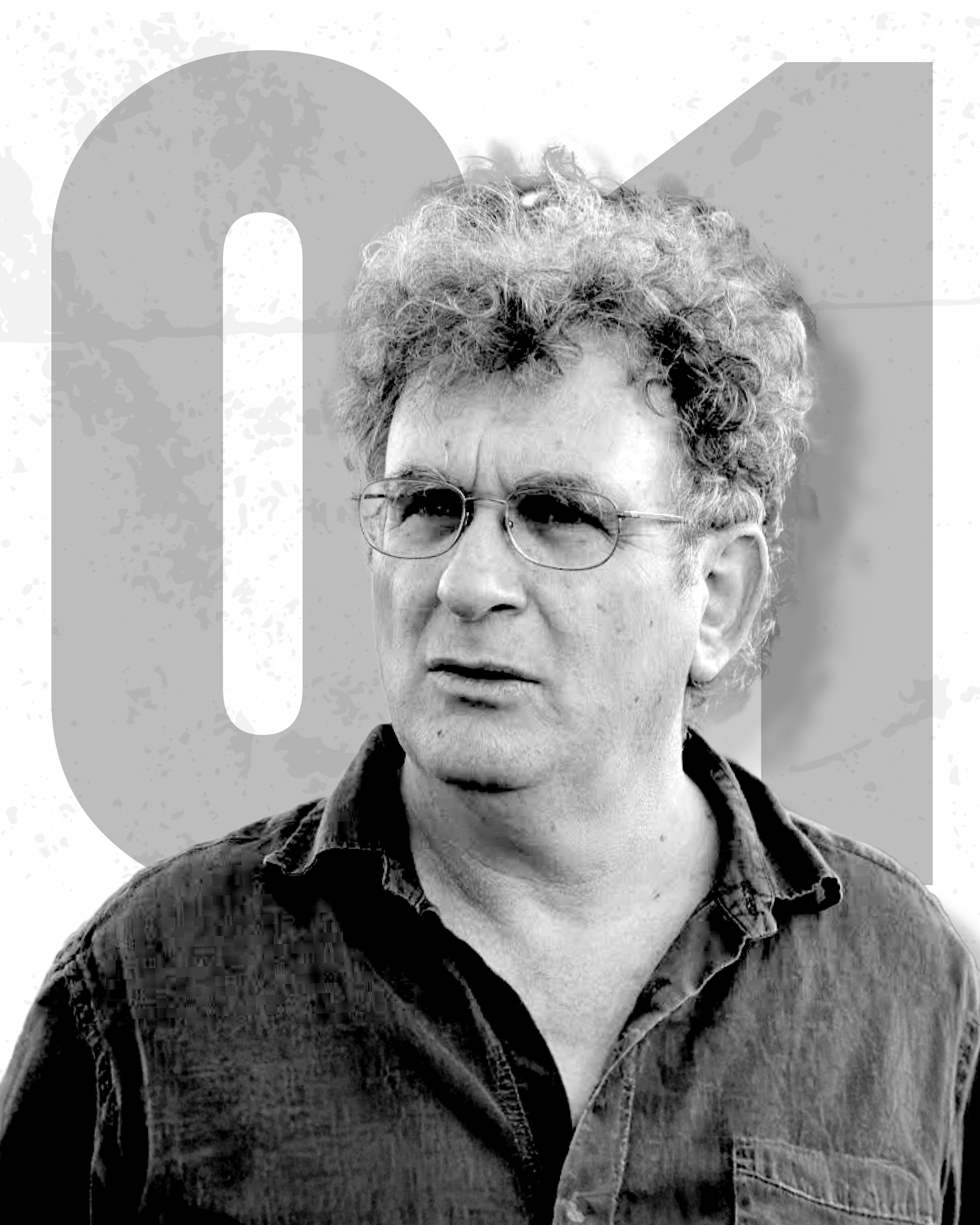

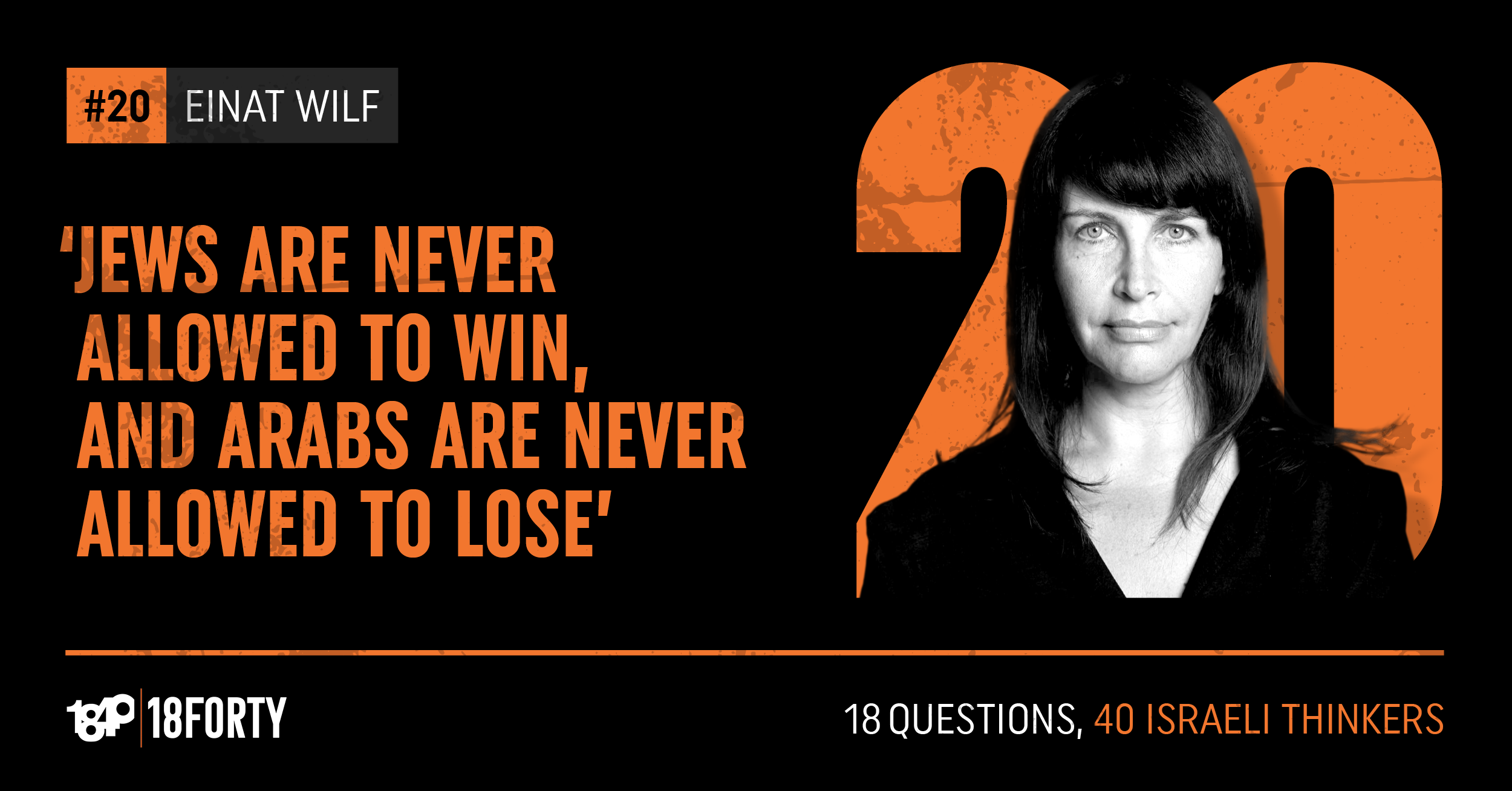

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

Summary

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

Once part of the Israeli left, Einat Wilf is a popular political thinker on Israel, Zionism, and foreign policy. Her 2020 co-authored book, “The War of Return,” outlines what she believes lies at the core of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict: the Palestinian people’s “Right of Return” is what makes this conflict unresolvable.

Einat served in Israel’s Knesset from 2010 to 2013 and now lectures and writes widely on contemporary issues. She is the author of seven books and hosts the “We Should All Be Zionists” podcast. She has a BA from Harvard, an MBA from INSEAD in France, and a PhD in Political Science from the University of Cambridge.

Now, Einat joins us to answer 18 questions on Israel, including what Palestinianism is, why Israel’s war aims are flawed, and the future of Gaza.

This interview was held on Nov. 25.

Here are our 18 questions:

- As an Israeli, and as a Jew, how are you feeling at this moment in Israeli history?

- What has been Israel’s greatest success and greatest mistake in its war against Hamas?

- How do you think Hamas views the outcome and aftermath of October 7—was it a success, in their eyes?

- What do you look for in deciding which Knesset party to vote for?

- Which is more important for Israel: Judaism or democracy?

- Should Israel treat its Jewish and non-Jewish citizens the same?

- What role should the Israeli government have in religious matters?

- Now that Israel already exists, what is the purpose of Zionism?

- Is opposing Zionism inherently antisemitic?

- Is the IDF the world’s most moral army?

- If you were making the case for Israel, where would you begin?

- Can questioning the actions of Israel’s government and army — even in the context of this war — be a valid form of love and patriotism?

- What do you think is the most legitimate criticism leveled against Israel today?

- Do you think peace between Israelis and Palestinians will happen within your lifetime?

- What should happen with Gaza and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict after the war?

- Is Israel properly handling the Iranian threat?

- Where do you identify on Israel’s political and religious spectrum, and do you have friends on the “other side”?

- Do you have more hope or fear for Israel and the Jewish People?

Transcripts are lightly edited—please excuse any imperfections.

Sruli Fruchter: Do you think peace between Israelis and Palestinians will happen within your lifetime?

Einat Wilf: It could be. They just need to stop being Palestinian-ists. They need to become Arabs, Muslims, whose worldview is compatible with the idea of sovereign Jews.

Sruli Fruchter: Do you think that will happen?

Einat Wilf: It could. Homo sapiens have changed their views on other issues.

Hello, my name is Einat Wilf. I am a thinker, a writer, and a speaker. This is 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers from 18Forty.

Sruli Fruchter: From 18Forty, this is 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers, and I’m your host, Sruli Fruchter. 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers is a podcast that interviews Israel’s leading voices to explore those critical questions people are having today on Zionism, the Israel-Hamas War, democracy, morality, Judaism, peace, Israel’s future, and so much more. Every week, we introduce you to fresh perspectives and challenging ideas about Israel from across the political spectrum that you won’t find anywhere else. So if you’re the kind of person who wants to learn, understand, and dive deeper into Israel, then join us on our journey as we pose 18 pressing questions to the 40 Israeli journalists, scholars, and religious thinkers you need to hear from today.

One of our most recommended thinkers by our audience was today’s guest, our 20th thinker for 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers, Dr. Einat Wilf, a political thinker on Israel, Zionism, and foreign policy today. She previously was in the Knesset in 2010 as the chair of the Education Committee and a member of the influential Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee and has since risen as a public intellectual, specifically on liberal Zionism and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. One of the big things to understanding Einat, and an important piece of context going into our interview, is that she used to be a self-described member of the Israeli left, but as she describes it, had some sort of an awakening. And I’ll quote here from an essay on her site.

I was born into the Israeli left. I grew up in the left. I was always a member of the left. I believed that the day that the Palestinians would have their own sovereign state would be the day when Israel would finally live in peace. But like many Israelis on the left, I lost the certainty I once had.

Why? Over the last 14 years, I have witnessed the inability of the Palestinians to utter the word “yes” when presented with repeated opportunities to attain sovereignty and statehood; I have lived through the bloody massacres by means of suicide bombings in cities within pre-1967 Israel following the Oslo Accords and then again after the failed Camp David negotiations in 2000; and I have experienced firsthand the increasing venom of anti-Israel rhetoric that only, very thinly, masks a deep and visceral hatred for the state and its people that cannot be explained by mere criticism for the policies of some of its elected governments.

This revelation for Einat is really key to understanding her viewpoints and her perspectives about how Israel should move forward in terms of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and in terms of national security. What’s interesting is that she defines herself even now, and I asked her this at the end of the interview as one of the classic questions, she defines herself as part of the Israeli left. But as I mentioned in the interview, her views on national security definitely do not, at least to me, and my understanding and the guests that I’ve interviewed, seem to align with Israel’s left today.

But at a certain point, labels are just labels and markers for us to understand someone’s political identity. Einat is the author of seven books, and her 2020 book that she co-authored, The War of Return: How Western Indulgence of the Palestinian Dream Has Obstructed the Path to Peace, captures the bulk of her main thesis for why the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is so stuck. In her view, the Palestinian right of return, the idea that all the Palestinians who have fled or were expelled from Israel in the 1948 war and all their descendants have a right to return to Israel as full citizens, she believes is the core of what makes this conflict so unsolvable. I’m not sure how much of that was explicitly said in the interview, but again, the context is crucial.

Einat was born and raised in Israel and served as an intelligence officer in the IDF, foreign policy advisor to Vice Prime Minister Shimon Peres, and a strategic consultant with McKinsey & Company. She has a BA from Harvard, an MBA from INSEAD in France, and a PhD in political science from Cambridge. It was a real pleasure to interview Einat, but before we get into the interview, as usual, if you have questions that you want us to ask or guests that you want us to feature, shoot us an email at info@18Forty.org and be sure to subscribe, rate, and share with friends so that we can reach new listeners. And so, without further ado, here is 18 Questions with Einat Wilf.

So, we’ll begin where we always do. As an Israeli and as a Jew, how are you feeling at this moment in Israeli history?

Einat Wilf: Overwhelmed, I guess. It’s tough not to consider the scale of the hostility. When you look at the Muslim world, at the Arab world, despite some encouraging signs, at the ideology that I’ve come to call Palestinianism, which is the complete devotion to the non-existence of a Jewish state, and the fact that there are still so many in the West who uphold that, who collaborate with that, who fuel that, one of the things that I find that people just fail to truly appreciate is how small the Jewish people are.

Because our story looms so large in the minds of so many people and civilizations that people fail to acknowledge how small we are as a people. So, yes, there’s at times a moment of being overwhelmed.

Sruli Fruchter: You’ve obviously been a thinker and someone involved in Israeli issues. I mean, more generally for the wider world, but also in Israeli society for many, many years and decades.

I think it’s fair to say. So I’m curious how you find the work you’re doing now differs and what particularly is overwhelming about it as opposed to in the last few decades, where there still has been, for those who were engaged, some exposure to that kind of hostility you’re describing.

Einat Wilf: So in terms of the work that I’m doing, a few things happened since October 7th. The first is, tragically, more people are willing to listen.

Both within Israel, more people are willing to listen, to accept that the Palestinians are not interested in any negotiable outcome, that their devotion is full and complete to the non-existence of a Jewish state anywhere in this land. So more people are willing to listen to that. For years, when I said that, it was a very tough message. It’s still a very tough message.

Sruli Fruchter: What’s tough about it?

Einat Wilf: That it’s total, that it’s absolute, that there’s nothing negotiable here. That nothing less than the complete transformation of the homo sapiens that currently uphold this ideology of Palestinian-ism, that nothing less than the complete transformation of that ideology, of that identity, will create any possibility for peace. That’s what’s tough. And, of course, Jews around the world and some non-Jews have been more willing to listen to the fact that what is going on in the West is a determined methodical process of greater respectability for anti-Zionism as a respectable mask that allows to conduct an assault on Jewish life with the Jews not being very prepared for that assault, because this time it appears with a new respectable mask.

So, again, more people have been willing to listen to that. And the other thing that has happened is, of course, that it’s exploded, that it’s become more open, more brazen, more confident, and in many ways it is now openly expressing its ultimate conclusion. I’ve called it for many years the placard strategy, because you see it more easily on placards and anti-Israel demonstrations. Those placards are ingeniously built as equations that say Israel, Zionism, sometimes they just draw the Star of David, equals.

And the placard strategy has been so successful that everyone knows what’s on the other side of the equation. And it’s never Israel, Zionism is the political movement for the liberation and self-determination of the Jewish people in their ancient homeland. Granted, a long placard, but that’s not what you see. The strategy has been so effective that everyone knows what’s on the other side of the equation sign.

Israel, Zionism, Star of David equals colonialism, imperialism, racism, apartheid, then it escalates, genocide, Nazism, now they’re even going to use the term Holocaust. If you’re in America in 2020, they’ll put white supremacy. So since October 7th, a new placard appeared, and it reads as follows. It says, keep the world clean.

And it has an image of a Star of David in a trash bin. And that is the logical conclusion of this policy. If you are going to equate Israel, Zionism, and the Star of David with all that is evil in the world, because the words are not chosen because they have any relation to reality. They are almost always the opposite of reality.

They’re chosen because they’re synonyms for evil. And if you create a 360 situation, academia, international organizations, journalism, media, social media placards, everywhere people hear that Israel, Zionism, Star of David equals evil, then the logical conclusion is to rid the world of that evil by any means necessary, which is also what we’ve seen much more after October 7th.

Sruli Fruchter: What has been Israel’s greatest success and greatest mistake in the current war against Hamas?

Einat Wilf: The greatest success has been Israel’s internal mobilization. I think for years people thought that Israelis are too tired, exhausted, too soft to sacrifice for our existence here as a sovereign people.

I think that no one thinks that anymore. The greatest failure has been the total conduct of the war. I wrote about it. Our leadership caved in on four issues that were crucial to our ability to win and therefore have deprived us of that, covering it with…

Sruli Fruchter: Which four issues are you…

Einat Wilf: I’ll say in a minute.

And they insisted on one issue, which was really stupid. So the four issues that they caved in, the first, they agreed to collaborate in the lie that Hamas doesn’t represent the Palestinians. When President Biden came here a few days after October 7th, we thought we would be slaughtered from every direction. People now try to downplay it, but we were incredibly close to annihilation.

If you look at Sinwar’s plan, it was very well thought of. Gaza then had Hezbollah launched what we now know they had, supported by Iran, having the Arabs of the West Bank, maybe even the Arabs within Israel, rise up, we would have been slaughtered. So it really meant a lot for America to send its aircraft carriers, for the American president to be here, to give a speech about the evil that was unleashed. I still believe that years and decades from now, when people will really begin to fathom how evil October 7th was, they will wonder why Israel was so restrained in its response.

But he said, after discussing all the evil that was unleashed, he said, but Hamas doesn’t represent the Palestinians. And I remember listening to that in real time and thinking, uh-oh, we’re going to pay dearly for this sentiment. And we did. Israel, I think, caved in too quickly to say that this is only a war against Hamas.

Sruli Fruchter: As a result, as opposed to a war against the Palestinians?

Einat Wilf: A war against Gaza at the minimum, and certainly against what I call Palestinian-ism, a war to defeat the ideology like Nazism, like imperial Japanese racial ideas, that the ideology has to die. We should have declared that as our goal. Nothing less. We should have said on October 7th, this ends here.

This is not about anything negotiable. The Homo sapiens that currently go by the name Palestinians will have to become a people who no longer believe in the complete destruction of the Jewish state. We can’t have that be their ideology.

Sruli Fruchter: Why didn’t Israel take that approach?

Einat Wilf: I think there was a mistaken notion that if you have limited goals, then you can achieve them sooner.

That maybe works in business, in retail, not in ideas, not in sacrifice, not in fighting. Someone sent me a remarkable quote by Ben-Gurion from February 1948. Not a lot of people know, in February 1948, the Jewish Yishuv is losing. People today believe that 1948 was some kind of like triumph and ethnic cleansing by an IDF that already then possessed tanks and airplanes.

People fail to understand how much it was like October 7th. So, in February 1948, the Jewish Yishuv is losing to the Arab militias, those that will one day be known as Palestinians. And Ben-Gurion meets with the heads of the Haganah, the defense forces, and he says the following. He says, look, we don’t know what our capabilities are.

They’re clearly limited. They’re not infinite. But we really don’t know what they are. He says our capabilities are actually related to our goals.

If we will have limited goals, we will have limited capabilities. If we will have great goals, we will have great capabilities. And he says, and who knows how far the Jewish People will go in order to liberate themselves and to be independent. So, I think we made the counter-Ben-Gurion mistake.

We set limited goals, which even then we didn’t achieve. So, mistake number one, Hamas doesn’t represent the Palestinians. First surrender.

Second surrender, directly related. We therefore agreed to resupply our enemy at a time of war because if we badly defined our enemy as only Hamas, rather than acknowledging that Hamas is of and for the Palestinians and for Palestinian-ism, then we are doing something that is unprecedented and unparalleled for any country at war. We are resupplying our enemy as it fights us, as it refuses to surrender. After it surrenders, fine. But before, and it holds our hostages, and we are resupplying the enemy.

Sruli Fruchter: Resupplying, you’re saying with aid?

Einat Wilf: It’s not aid. It’s constantly supply. No, we’re sending trucks into Gaza that are keeping Hamas in power.

We are resupplying the enemy. This is giving them money. This is giving them control. This is supply.

Sruli Fruchter: So I have two brief questions before we get to the other two concessions. One is, on the point of limited goals, it’s interesting to hear you say that Israel should have declared, I guess, a war or some sort of campaign against the ideology because that’s what many have actually criticized Israel for doing, was saying that Hamas is not a group, but it’s an ideology. And an ideology can’t be eradicated through military means. So I’m curious, A, how you understand that.

And then the second point is, what do you think should have been done with humanitarian aid and other things like that, which Israel has also been criticized for?

Einat Wilf: So that is exactly wrong. It’s not that Hamas itself is an ideology. Hamas is an organization. The ideology is Palestinian-ism, which rests on antisemitism and Islamic ideas.

I argue that Palestinianism brings the worst of the Arab and Islamic world and the worst of the Western world. And it created a unique identity that is really devoted to the non-existence of the Jewish people as a sovereign people. Of course ideologies can be defeated.

Sruli Fruchter: I think through war was the question that people had.

Einat Wilf: Of course ideologies can be defeated through war. When Israel started to operate in Gaza, people said what Israel is doing will further radicalize the Palestinians. And I remember thinking, how much further can they be radicalized? And what people don’t understand is that it’s exactly the opposite. When people are defeated, it’s not just the war per se.

You have to be defeated. You have to face the ruin to which your ideology has brought you. When you face that ruin, when a people faces the ruin to which their ideology has brought them, a window opens. A window that says maybe the ideology was not such a great idea given where it has led us.

And the tragedy of the conflict, the tragedy I think of the Palestinians and consequently of Israelis is that every time from 1936, 37, 38 to the present, every time that Palestinians could have faced the ruin that is their ideology, that is their devotion to no Jewish state, they were always fueled, salvaged and supported by some power, Nazis, pan-Arabists, Soviets, Western collaborators, Iranians, to say no, no, you were not defeated. You don’t need to go through a process of reckoning. You don’t need to change anything. This is justice. This is rights. Keep fighting. The Jewish state will one day disappear. So the problem is not that ideologies cannot be defeated.

Of course ideologies can be defeated. The problem is that a lot of people don’t want the ideology of killing the Jews to be defeated. But at the minimum, we as the Jews should insist that this ideology should die.

Sruli Fruchter: How does a war accomplish that? I mean, if it is a war, then what more would you have liked to see in how Israel conducted the war? I think the current numbers now is that 80% of Gaza’s infrastructure is destroyed.

There’s hundreds of thousands, maybe even the millions that are displaced. What do you think more should have been done in terms of the military approach that would have led to a dismantling of this ideology or an erasure of this ideology?

Einat Wilf: So it’s a combination. You need to combine the ruin with surrender. Right now, people are calling on a ceasefire, on negotiations.

The whole idea that we’re negotiating for the hostages is insane. From the first day, it should have been made clear that there’s no negotiating. Israel owes them nothing, and Israel will get every support and do everything to release them, but you don’t get to kidnap people from their beds on a Shabbat morning and then expect negotiations. So you’re asking what more could have been done, and that relates to what I refuse to call humanitarian aid.

It is a resupply to the enemy at a time of war. So if Israel had done things right, it would have made it clear that the enemy is Palestinian-ism. At the minimum, it’s Gaza. We should have said to the American president, thank you for everything you’re doing, but Hamas does represent the Palestinians in the deepest sense of the word.

It represents the deepest Palestinian ethos of no Jewish state. So we’re going to assume that Hamas represents the Palestinians because that’s where all the euphoria on October 7th. This is the entire war doctrine of Hamas that is based on pre-stashing weapons all throughout Gaza, on creating an integrated weaponized landscape. So right now, all the data points to the fact that Hamas does represent the Palestinians, and this is going to be our working assumption.

We would love to be proven wrong, but the burden of proof is on them, releasing hostages, giving information, surrendering. If Hamas as a collective will not surrender, then individuals surrender. Israel, for example, could have allocated an area, let’s say in north Gaza, that is completely clean and basically say anyone who individually surrenders can come. An individual surrender means that they are expunged from the records of unrest refugees.

They describe their desire to live next to a Jewish state. They are now refugees. They possess no right of return. They basically let go of the core tenets of Palestinian-ism.

We have not put such demands at all. We have not expressed those demands. And we should have made it clear that from our borders, the borders that were breached, through which we were invaded, we are not resupplying the enemy until it surrenders. We will provide aid to individuals who surrender.

That’s fine. I think that could have been a great thing to do. Create a zone, say anyone who individually surrenders will be supplied, but only there. Anywhere else, it’s war.

We’re not supplying our enemy at a time of war. Egypt is welcome to supply them, not us.

Sruli Fruchter: So one brief follow-up and then making it to the other two concessions you mentioned. So when people will accuse Israel of say, using the food or the supplies that are going into Gaza as leveraging that in terms of the war against the Palestinian people or against Gaza, against Hamas in whatever fashion, you’re not saying you disagree with whether or not that’s true. You’re disagreeing whether or not that that’s wrong of Israel to do, to make sure I’m understanding correctly.

Einat Wilf: I’m disagreeing on both. First, unfortunately, Israel did not use it. Israel has resupplied its enemy all the time, which shows you that again, in a way that is very typical to the Israeli and often Jewish condition, we comply with rules that are employed for no one but us.

And then we got no credit for complying with these invented rules. So I say we should comply with the international standard, which is you do not supply your enemy until it surrenders.

Sruli Fruchter: And then the other two concessions that you mentioned, I know we got into a little bit of a follow-up.

Einat Wilf: The other two concessions are, of course, the fact that we treated Qatar as some useful or benevolent element here rather than realizing them for the enemy that they are, for the very insidious influence that they are and for the fact that from October 7th, they have been very busy at ensuring that Hamas remains in power very successfully.

And the fourth concession is, again, to agree that Egypt doesn’t exist. For many months, we were not on the borders with Egypt. We pretended as if there’s no border with Egypt. Even in terms of the supplies, we know that there was a very thriving kind of exchange above and below ground with Egypt.

Suddenly, there’s no border. The pressure on Egypt, everywhere in the world, it’s acknowledged that you should allow people to escape an area of war. No pressure on Egypt. No mention that Egypt can resupply if it feels that it’s necessary.

We pretended as if Egypt doesn’t exist and totally ignored their complete double game in resupplying Hamas.

Sruli Fruchter: How do you think Hamas views the outcome and aftermath of October 7th? Was it a success in their eyes?

Einat Wilf: So far, a great success.

Sruli Fruchter: Why do you say so?

Einat Wilf: October 7th itself, for them, that will remain something that they were able to do. And from their perspective, they have yet to pay a price.

People look at the destruction in Gaza, the people who were killed. From the perspective of Hamas, that’s not a price. They remain firmly in power. They hold the hostages.

The pressure is on Israel to negotiate. And people somehow accept that Israel should submit to the Hamas demand, which is to go back to October 6th. So, from their perspective, they haven’t yet paid a price.

Sruli Fruchter: What do you look for in deciding which Knesset party to vote for?

Einat Wilf: Track record, I guess.

Sruli Fruchter: Showing what?

Einat Wilf: Showing that they understand where we live, that they understand our enemies, and that they have competently dealt with our enemies, that they have competently dealt with Israel’s need to be strong against our enemies. That’s what I’m looking for.

Sruli Fruchter: Would you say that national security is the most important thing for you when deciding which Knesset party you’re voting for?

Einat Wilf: Mostly.

Sruli Fruchter: What are the other things that you’re considering?

Einat Wilf: I would say competence in those issues. Religion and state are important for me. Yeah, mostly.

Sruli Fruchter: Which is more important for Israel, Judaism or democracy?

Einat Wilf: I’ll start from the assumption that let me challenge the basic assumption. If Israel is not Jewish, it’s not a democracy.

Therefore, it must first be Jewish.

Sruli Fruchter: Why would that be if it’s not Jewish, that it’s not a democracy?

Einat Wilf: Broadly speaking, not a lot of people are aware of this, that nationalism was actually key to democracy. Americans in particular are very blind to how nationalist their democracy is. They really think they live in some universal democracy.

But generally, historically, the expansion of democracy happened with the expansion of nationalism. The reason is, of course, is that the idea of one person, one vote is a very radical idea. It’s incredibly recent. Even in America, it’s fairly recent.

America still doesn’t employ it to the full extent. One person, one vote is a very radical idea. The willingness of people to live in one person, one vote communities rested on the assumption that there is a certain level of trust between the members of the community. Because a one person, one vote community means that I give you the equal power over my life as I have over my life.

There needs to be a certain element of trust for me to do that. Historically, the fountains of trust lay in the sense of nation, religion, language, people. So, the creation of nation states allowed for the expansion of democracy where you have one person, one vote with the underlying assumption that by and large the people share a common goal. In Israel, this is what the Jewish people provide.

The Jewish people are the foundation of the Israeli democracy. Israel is the nation state of the Jewish people and that allows it to be a democracy. Now, in this region in particular, if it’s not a Jewish state, then it’s an Arab state. There’s no other option.

So, there’s no Arab democracy, never have been. Sometimes people say, well, that’s racist to say. No, it’s empirical. As of now, there has never been any Arab country that has been a democracy.

So, when people say, well, we can have a democracy between the river and the sea, so an Arab majority country with a Jewish minority and it will be a democracy, you are asking people to believe the following. You are asking people to believe that between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea will arise the first ever Arab democracy who will be the first ever Arab and Muslim country to treat its Jews as equals. And you are asking the Jewish people to forego their one state, their hard fought state which they dreamt and sacrificed for, for the never-having-before existed unicorn of an Arab democracy that will treat its Jews, its Jewish minority as equals. I’d say it’s a bit of a stretch.

Sruli Fruchter: So, do you ever see the Jewish character and democratic character of Israel coming into conflict?

Einat Wilf: Nope.

Sruli Fruchter: Why do you think some people do?

Einat Wilf: Because they don’t get it.

Sruli Fruchter: What does the Jewish character look like manifested in Israel? Is it just that there is, is it just a demographic issue or is there a part of the makeup of the state and of the culture that carries it?

Einat Wilf: So, I have a long talk, people are welcome to look it up on YouTube, which is called What Do We Mean When We Call Israel the Jewish State? And it goes through the entirety of Jewish history and what it means to be Jewish and the different conceptions of what it means to be Jewish. And I especially look at the last 200 years since emancipation, since the whole idea of what it means to be Jewish really begins to kind of enter into various interpretations as a result of emancipation, the idea of the nation state, the idea of the citizen of the secular republic.

And I end the talk by giving the following definition for the Jewish state. I say that the Jewish state is the one state in the world where we get to argue about what it means to be the Jewish state. And I explain that this argumentation is foundational to Israel and, of course, to its democracy. The reason that this argumentation persists is for two reasons.

The first is that the Jews have no pope … And the second is, of course, the fact that we are now a civilization that is based on nearly 4,000 years of texts, sayings, interpretations, events. Now, imagine that you’re a lawyer, you have 4,000 years of texts, large share of them, pretty opaque, and now you want to make an argument for something. You can literally argue for anything you want.

So as a member of Knesset, I remember what sit at the Knesset plenary. And every day at the Knesset, regardless of what the official title of the debate is, is always a debate on what it means to be the Jewish state. We should do A because we’re the Jewish state. We should actually do the opposite of A because we’re the Jewish state.

And both people have a case. So my argument is that at the foundation of Israel’s democracy lies Jewish argumentation and that the essence of Israel’s Jewish character is Jewish argumentation. So no, they will never be in conflict.

Sruli Fruchter: Should Israel treat its Jewish and non-Jewish citizens the same?

Einat Wilf: In what sense? The answer is yes, but why? I mean, I’m not sure I understand the question.

Sruli Fruchter: But where do you see that there would be a distinction?

Einat Wilf: Within the State of Israel, completely equal.

Sruli Fruchter: As opposed to?

Einat Wilf: In terms of who gets naturalized, who gets to become a citizen of the State of Israel. So a lot of people make the mistake of thinking that discriminating in the naturalization process means you’re discriminating against the citizens. But it is by definition not the same.

The citizens, once they are citizens, are all equal by law … But in terms of the naturalization process, Israel can continue to be committed to being partial to Jewish immigration.

Sruli Fruchter: How do you see this question factor into Yehuda VeShomron and the West Bank, particularly with—

Einat Wilf: They’re not part of Israel.

Sruli Fruchter: Many people see it as a technicality. And I guess the pushback that they give is they say that technically maybe it’s not part of Israel, but effectively the West Bank does, Yehuda VeShomron does function.

Einat Wilf: It’s not. A government fell on this supposed technicality.

Sruli Fruchter: Which government?

Einat Wilf: The Bennett government. He was not willing to call the bluff of the settlers. The list of arrangements that allows Jewish citizens to live abroad as if they’re still in Israel was a temporary mechanism and it was about to end. And because the settler right wanted to bring down the Bennett government, they were willing to allow this to end, even though it hurt them.

And Bennett, that’s his biggest failure. He failed to call their bluff. He should have just called their bluff.

Sruli Fruchter: Can you clarify what would have ended during his?

Einat Wilf: All the systems of arrangements, government arrangements that allow Jewish citizens who live in non-Israeli territory to behave as if they live in Israel.

Sruli Fruchter: So why do you think that there’s been such a consistent tolerance between right and left governments since Israel’s founding of the settlements communities in Yehuda VeShomron and the West Bank?

Einat Wilf: I mean, it’s a very limited tolerance when we have other priorities such as disengagement. There’s zero tolerance. But by and large, of course, the supposed tolerance comes from the fact that as long as the Palestinian vision is from the river to the sea, no Jewish state, then even Israelis who are not great supporters of the settlement, such as myself, say, OK, but it has. That’s not what the conflict is about anyway.

Sruli Fruchter: What role should the Israeli government have in religious matters?

Einat Wilf: None.

Sruli Fruchter: So how do you see the relationship between religion and state? You mentioned that’s something that’s important to you. I’m curious how you envision that manifesting.

Einat Wilf: So not a lot of political words sound better in Hebrew, but this term does.

I call it from Rabbanut to Ribbonut.

From Rabbinate to Sovereignty.

Einat Wilf: We are still not over exile. The Jewish People created very impressive forms for a people in exile, people who lacked any sovereignty anywhere. That was rabbinical Judaism. Rabbinical Judaism has a lot of remarkable aspects of self-organizing elements.

They are utterly irrelevant for a sovereign state. The fact that we still keep them are undermining the sovereignty of the state. Again, people can be rabbis like they can be teachers, but they should have zero authority on things that are matters of state. We need to complete the Zionist revolution, which is to be a fully sovereign people who have organizations and modes of thinking that fit a sovereign people rather than a people in exile.

Sruli Fruchter: Now that Israel already exists, what’s the purpose of Zionism?

Einat Wilf: To get the world to live with Jewish sovereignty. It’s a bit of comparative with feminism. Feminism was not just about giving women the right to vote or giving women education or control of their finances. It’s ultimately a revolution that accepts women as full human beings.

With Jews, the same idea exists. Zionism was about liberating Jews, giving them self-determination. The state of Israel was the means of that liberation to give them sovereignty, mastery of their fate. But the fact that so many in the world find the idea of sovereign Jews so impossible shows you how far Zionism is from having achieved its goal.

Zionism will have achieved its goal when the idea of sovereign Jews, a Jewish state, will be an absolute non-issue, that you will not have a complete nation devoted to the destruction of Jewish sovereignty. You will not have systems, civilizations, religions who have the idea that Jews cannot be equal, that Jews cannot be sovereign. That’s when Zionism achieves its goal.

Sruli Fruchter: Is opposing Zionism inherently antisemitic?

Einat Wilf: In practice … Let me give you an example. Rosa Luxemburg, a Jew. If you look at her writings on communism and nationalism, she was equally angry at the Czechs, at the Poles, at the Ukrainians and the Jews for pursuing the idea of a nation. Great.

If you can find me a modern Rosa Luxemburg who is equally incensed at five I’m not saying 200 five, ten more nations that are independent, I’ll grant and Israel is just one of the list I’ll grant them that they are true, pure, non-antisemitic anti-Zionists. But in practice, ever since anti-Zionism exists as an idea, which is about a century, everywhere that anti-Zionism has come to dominate a country, a society, a political party, an organization, a campus, two things happen. The first is the environment turns hostile to Jewish life. Even as the anti-Zionists claim that they love Jews, they have nothing against Jews, Jews are great.

And the reason, of course, is that anti-Zionism is merely the respectable replacement, even if they don’t think so. The laws in Iraq and in Egypt were written as laws against Zionists. But then what happened? The Jews were then charged with Zionism. And a Jew will never be able to oppose the charge of Zionism because, heaven forbid, they just celebrated Passover and they said to next year in Jerusalem.

That’s how it operated everywhere. This is what you’re seeing, the playbook, the same playbook that operated in Iraq and Egypt is now operating on campus. I think it’s Columbia now, they’re trying to get Hillel off campus. Hillel, the center of Jewish life.

By what means? They’re claiming that Hillel is Zionist. That’s the playbook. You begin by saying that you’re only against Zionists, you establish that, and then you begin to charge every Jewish expression as being Zionist and claiming to have that go. So, number one that happens, the environment turns hostile to Jewish life, even as the anti-Zionists claim that they love Jews, even if they’re Jews themselves.

Step two, if this is not stopped, fought against, no Jews are left. That’s it. And it’s always the same. So you have the complete ethnic cleansing of Jews from the Arab world in the name of Zionism.

In the two decades when the Arab world was obsessed with anti-Zionism at the height of pan-Arabism, from Morocco to Afghanistan, no Jews are left. The Soviet Union claimed to not even know that people were Jewish. The only problem was Zionists. And we know exactly how the Soviet Union treated its Jews.

Poland in 1968, a little-known case. There were Jews who were willing to stay in Poland after World War II, kind of picking themselves up, believing in the promise of brotherhood and socialist and communist utopia. In 1968, inspired by Soviet anti-Zionism, Poland goes through a wave of anti-Zionism. In the name of anti-Zionism, Jewish professors are removed from power.

It always starts among the elite, the educated. People are somehow shocked today that it’s in universities. But this is how ideologies get promoted, by having the respectability of the elites. That’s why the people will follow.

So Jews are removed from positions of power in the name of Zionism. Nothing against Jews, but the Jews are removed from power. And within a few years, even less, I think one year, no Jews are left in Poland, whatever few Jews remained. Some left and some committed suicide, unable to just take that betrayal.

So the playbook is the same. So anti-Zionism, in practice, always leads to no Jews.

Sruli Fruchter: It’s interesting to hear you say that, because as you were speaking earlier about Palestinian-ism, as you called it, and waging war on that ideology, I was thinking as you were answering this question that the same risk you’re describing and the fact that Zionism is so entrenched and enmeshed in Jewish identity and in the Jewish People, and so therefore when people, you know, in theory may be waging war against an ideology, they end up waging war against a people. Why does that same risk not come into play when waging war against Palestinian-ism, if that’s also so enmeshed with the Palestinian people?

Einat Wilf: I’ll separate it for two things.

First of all, one could claim that Jews merely have to accept the Satmar vision. They’ll still be Jewish. They’ll just support, as one of my students said, not Zionism now, Zionism later, okay, when the Messiah comes. And you could say, look, you can be Jewish without a state.

And I can assure you that if the state of Israel, apropos destroying ideology, if the State of Israel will be destroyed by some violent cataclysm, I assure you that the Satmar Jews will be the dominant sect of Judaism because they will be the ones who said we told you so. So this is exactly an example actually of how you change ideology. It’s not that you become anti-Zionist in the broad sense. Even Satmar are Zionist in the sense that the ultimate goal of the Jewish people is restoration in their homeland.

But I guess it’s the kind of Zionism that some of our enemies are willing to live with. Not sure, but supposedly. Palestinian-ism is a much more recent creation. And it is, as I said, it brings together the worst of Islam and the worst of the Western world for the singular purpose of destroying the Jewish state.

Should I tell you that sometimes I also wonder if there’s any chance because, and it’s also to your question, when will Zionism have achieved its goal? When the world is willing to accept sovereign, confident Jews with a spine without trying to kill them. Will the world ever be able to accept confident Jews? Will the world ever be able to accept Jews having a spine? I have moments of despair and questioning. But fundamentally, as someone who studied Palestinian-ism as an ideology and I saw it develop, it’s fairly recent. It’s a terrible ideology.

And yeah, you could argue that Nazism had a real basis in German civilization, the Teutonic legends, and Wagner. But ultimately, through a very methodical process, it was stamped out of the Germans. And even if some people say it’s underneath, good enough. If we could get Palestinian-ism to occupy the same place as Nazism today, we’ll be in a good place.

Sruli Fruchter: Is the IDF the world’s most moral army?

Einat Wilf: There’s the joke that says not only is the answer yes, but it’s the only army that’s even competing. I’ll explain why and why it’s the only army that’s even competing. Because Jews someone also once made a comment the Jews are the only nation that’s expected to be a Christian nation. And not the marauding medieval Christians, the Jesus-turned-the-other-cheek Christians.

The Jews are the only ones who are basically expected to wage wars without waging wars. Every time you hear this refrain, Israel has a right to defend itself, except like this, except like this, except like this, except like this, effectively no right to defend itself. So when Israel wages wars, it does so under an insane magnifying glass. So even if we want it to be less moral, there’s nowhere to do that.

Sruli Fruchter: Is that a bad thing? Meaning then who should be the police officer, so to speak, for how wars are waged?

Einat Wilf: I have no problem with international standards, except that they’re never employed when it comes to Jews. With Jews, you invent standards that are not applied to anyone else.

Sruli Fruchter: Are they applied differently with Russia and Ukraine than they are with Israel and Hamas?

Einat Wilf: They’re not applied to anyone. Any military expert will tell you that what Israel is doing in Gaza is unprecedented, unparalleled, and exemplary.

That no military has ever taken such measures to wage war. Again, even what we started with, the fact that Israel was expected to declare war just against a sub, sub, sub section of those who are actually at war with it. I compare it to Roosevelt declaring on December 7, 1941, war against Japanese pilots. He would say that America is now mobilizing to find Japanese pilots and kill them.

That’s basically what we’ve been asked to do. Who has ever been asked to do that in any war? So only when it comes to Israel, certain ideas are employed uniquely to Israel, and then people pretend that they’re normal, but they’re not normal. So Israel is the only moral military in the world, as I said, we’re the only one competing, because we’re constantly forced to uphold insane standards that no one else would. And I would say that it comes from even something deeper, the desire to prevent Jews from winning.

So for the last century, we’re stuck in a cycle where Jews are never allowed to win and Arabs are never allowed to lose, which is, as you can see, a guarantor of forever war. The way that wars actually end is one side clearly losing, sometimes even officially surrendering, and one side clearly winning and operating based on that, operating based on the acknowledgement of defeat and victory. The Arabs are the only ones who are constantly allowed to go back to square one. They attack Israel, they fail to defeat Israel, and then they are restored to the conditions when they attacked Israel.

We’re seeing it happening now in real time.

Sruli Fruchter: But isn’t the Russia-Ukraine war an example of where that might not necessarily apply, meaning that there is a warrant of arrest for Putin by the ICC, and that there is, in fact, from Ukraine’s perspective, at least, while the US is arming Ukraine and trying to help Ukraine in the war against Russia, in defense against Russia, there is an encouragement of negotiations for political settlement with Russia so that there can be peace. So why is that model, at least, A, I guess, the scrutiny placed on Russia, and the encouragement that Ukraine try and find a political negotiation with Russia?

Einat Wilf: Well, there’s no scrutiny, not on Ukraine, not on Russia, and we remain to see how exactly this thing ends. But we see that in our case, let’s talk about Lebanon for a minute.

For 18 years, there was a supposed ceasefire embedded in a UN resolution, 1701, which only Israel implemented. Not Hezbollah, not Lebanon, not the Lebanese military, not the UN forces. We know that they did not do their share. We know the opposite.

We know that they built on our borders the means for our annihilation. Okay. Then Lebanon, through Hezbollah, attacks Israel unprovoked on October 8th. Now, some people say, oh, if Israel will cease operations in Gaza, then Hezbollah will no longer attack Israel.

And I’m thinking, excuse me? You’re accepting their terms? No. Preventing Israel from taking effective action in Gaza is not a legal and legitimate cause for war. So this is an unprovoked attack from Lebanese sovereign territory. Again, all these plays also with non-state actors.

Lebanon is not really responsible. Okay. So unprovoked attack on Israel, completely against the resolution, right? For 11 months, Israel begs the world to implement the resolution. Nothing gets done.

Then Israel starts to effectively dismantle Hezbollah. Within days of Israel taking action, what does the world say? Ceasefire. 1701. No, you don’t get to restore the conditions that you just broke.

And this is always the pattern that we have with wars with Israel, which is why you constantly have wars. Because you are incentivizing the enemies to try and try and try again. Rather than take actions that, for example, were understood to be the only actions that make it clear that a war is over, change in borders and territory, population, official surrenders, compensations.

Sruli Fruchter: If you were making the case for Israel, where would you begin?

Einat Wilf: The numbers.

Sruli Fruchter: Which numbers?

Einat Wilf: The number of Jews. This is the one thing that people seem to not understand, that we are here in Israel, about 7 million Jews, 15 million in the entire world, still haven’t made up our numbers since the actual genocide conducted against the Jewish People. We are surrounded by half a billion Arabs, which again, despite some positive developments in some places in the Gulf, remain deeply committed to the non-existence of Jews as a sovereign people. Abetted and fueled by a Western civilization and a Russian civilization that still has deep undercurrents of being unable to accept the idea of Jews with power, confident Jews.

And that in all that, we are 7 million in Israel and 15 million worldwide. People don’t really get what those numbers mean.

Sruli Fruchter: Can questioning the actions of Israel’s government and army, even in the context of this war, be considered a valid form of love and patriotism?

Einat Wilf: Only if you’ve actually shown yourself to be loving and patriotic, most of the time. If all you’ve ever done is criticize, then I doubt that you can claim.

Just as in a personal relationship, if all you do is criticize a person, I doubt they will find you very loving. If you have proven yourself a lifetime of a loving partner, and then when your partner does something wrong, you not only criticize them, but you tell them how you think they can do better. You offer to help them to do better. Sure.

But that’s rarely what I see when people claim to be criticizing Israel.

Sruli Fruchter: What do you see?

Einat Wilf: Typically the placard strategy. When people tell me, how can you differentiate? I say step one, I want to see if anyone uses any of the placard-strategy words. That’s not a good faith criticism.

Sruli Fruchter: So I guess I’m curious where within the very wide tent, let’s say of the pro-Israel community, there are many who would apply that same type of dismissal, I’ll say for lack of a better term, to organizations that are more liberal or left-leaning in Judaism or Zionism, such as J Street. Do you believe in those types of cases that is an exemplary? Meaning, how intense can the criticism be? Is that parallel to how intense the partnership is, or is it that once there’s a partnership and sense of an identity that there’s a pro-Israel mentality or a Zionist mentality, then the criticism is just up to the person or the organization?

Einat Wilf: So J Street is a great example where you would be hard-pressed to find the loving patriotic part. When J Street was established, they were looking for legitimacy in Israel because no one initially was willing to talk to them. I was a member of Knesset on behalf of the Labor Party, and Jeremy Ben-Ami came to me.

And I said, look, Jeremy, I have no problem with your program. Two states, fine, I support that. But if you want me to actually support you as an Israeli member of Knesset, I need to know two things. First, that you will never take actions that imply that Israelis need to be shown the light, that Israelis do not know what’s good for them, and that you in America will pressure your administration so that we will do what’s good for us according to you.

I told him, especially as an elected member of a sovereign state, that is the most offensive thing you can do. So it’s not about your actual program, but whether you respect that Israelis living here actually know what’s good for them. Two, that you will not allow in the name of pro-Israel, pro-peace, people into your organization that are certainly not pro-Israel. Now, I clearly failed on both accounts.

J Street proceeded to become a prescriptive organization that tells Israel what it should do and to try to mobilize Americans to tell Israel what it should do. And two, it allowed a lot of people into the movement who are clearly not pro-Israel. I know from a lot of Israelis who over the years went to J Street conferences, they would come back appalled that anything anti-Israel you would say would get tremendous applause. But there was nothing in the conference about great things that Israel’s doing, showcasing good things about Israel, and that if they said good things about Israel, it would never get applause.

So what J Street fails is on the fact that you really need to show that you’re loving before you earn the right in a particular instance to criticize.

Sruli Fruchter: So very briefly, I’m curious. Let’s say with judicial reform, which was a much bigger conversation, I think, in Israel, and I think the threat that people saw it having, or I guess the opponents of it saw it having towards Israeli democracy. And then in the diaspora, how many responded with shock, with appall for those who were against it as well.

And in that type of instance, do you believe that influence from outside of Israel against judicial reform or against something that they see as a threat to the Jewish state is justified, still unjustified, and it’s like an absolute?

Einat Wilf: Absolutely unjustified. I had some very close friends who kind of wrote an open letter. They invited me to join and I wouldn’t join. Open letter calling Jews and others to intervene.

No, and that’s also part of my criticism within Israel. I think, especially my political camp, the supposed Israeli left, they’ve given up on the lost art of convincing, of actually making your case, constantly looking for shortcuts by trying to have outside influence, outside pressure. By the way, this is my claim to the settlers, that they have achieved the settlement enterprise by circumventing the Israeli public. So my position on settlements right now is sovereignty before settlements.

You want to settle, make sure that there is a Knesset vote to annex those territories. If they’re not annexed, you do not go and like settle in the middle of the night. All of that I think has been a disaster. So I think a lot of people in Israel have forgotten the art of making your case, of actually trying to convince the Israeli public that you have the better understanding of reality, that you have the better prescriptions, and therefore people go in all kinds of ways.

So the settlers, by kind of capturing systems and doing it underneath the radar, by people appealing to outside help, whether from the right or the left, people, I mean, it’s always great to take to the street, but the notion that you try to use levers of power which are not about convincing. So yeah, I try to bring back the old art of making your political case.

Sruli Fruchter: What do you think is the most legitimate criticism leveled against Israel today?

Einat Wilf: That it is too, but I don’t think it’s a criticism that people level. It’s my criticism that it’s too busy trying to surrender to made-up rules rather than pursuing what’s really important for our country.

Sruli Fruchter: So of what people generally do criticize Israel with, of all those things, which do you think is the most legitimate?

Einat Wilf: None.

Sruli Fruchter: Even if it’s not totally legitimate but has some merit to it.

Einat Wilf: Give me an example because most of what I hear has no basis, but give me an example of what you think.

Sruli Fruchter: Well, no, there’s so much out there that it’s hard for us to select.

Einat Wilf: I haven’t yet heard anything that is I mean, from the criticisms that are essentially variations on the placard strategy, they’re variations on the placard strategy.

Sruli Fruchter: You don’t hear more moderate types of criticisms that you feel are more balanced?

Einat Wilf: Like what?

Sruli Fruchter: More moderate criticisms either about conduct of the war or about Jews and democracy. I don’t want to personally list anything because I’m curious from, I guess, your experience if there’s something there.

Einat Wilf: I don’t hear anything that stands up to any scrutiny.

Like when people say the conduct of the war, okay. As I said, there’s no military expert. So if you’re not a military expert, I have no interest in your criticism of the conduct of the war. Can you tell me how the war could have been conducted differently? I have criticism, but as I said, it’s not the criticism as people say that we define the enemy too narrowly, that we are resupplying the enemy.

That’s not your typical criticisms of how the war is conducted. If people really understand what Hamas have built there, military experts have to go to like some island in Japan and some fortresses from 2,000 years ago to compare to what Gaza has built. I think it’s important to devote a minute to that. What the Palestinians have built for several years now, more than a decade, with billions from the outside world, it’s not urban warfare.

Urban warfare is a bunch of guys hiding in buildings. This is an integrated weaponized urban landscape. It’s taking the entire Gaza Strip and making it into a single weapon of war by connecting hundreds of weapons stashes, and all the stashes were prepared ahead of time in mosques, schools, kindergartens, homes. You can do that only among a supportive population.

All those stashes which were prepared ahead of time were connected with hundreds of piers through hundreds of kilometers of tunnels. The butchers, except on October 7th when they wore some uniform, go around in civilian clothing among a supportive population, above ground in civilian clothing or under the tunnels. They go up, the weapons wait for them. When you begin to understand what has been built in Gaza, the conduct of Israel, and as I said, when people will begin to appreciate, decades from now, the evil that was unleashed on October 7th, they will not understand how Israel was so restrained.

Sruli Fruchter: Does it concern you at all that there’s such a gap between the criticism that your, or I guess your perspective on Israel and the war versus the world more generally?

Einat Wilf: Of course. But that’s how it works. I wrote a piece which quoted Ahad Ha’am. He wrote a piece 140 years ago called “Chatzi Nechama,” “Half Solace.”

And where did he find half solace? He was concerned that the Jews, as a result of emancipation, the walls were coming down, the Jews were leaving the ghettos, and they were now surrounded by Christian or Christian secular society that basically told them how evil they were. And he was concerned that they will internalize that notion of what it means to be Jewish. He called it the mechanism of general agreement. Because you’re surrounded by it, then doubt begins to creep in.

And where did he find half solace? In the blood libel, the original one. Because he said Jews knew that the blood libel, where Jews drink the blood of non-Jewish children for their rituals, is wrong. He says this is one knowledge that Jews could be certain of. And he hoped that that would help steel the Jews for the possibility that, yes, the whole world can be wrong and the Jews be right.

So I find half solace in Ahad Ha’am’s speech. I find half solace in the fact that there is a historical continuum. So that when people tell me right now, no, this time it’s different. This time we’re only annoyed with the conduct of the war.

I have enough of a history to know that the burden of proof for making that claim is entirely on those making that claim. And yes, it pains me to see Israelis and Jews work so hard at trying to disprove that. Sartre said that it’s not that the antisemite doesn’t know what he’s doing when he lobs all these claims at the Jew. He wants to see the Jew sit and explain and expose their empty pockets and say that they’re not all those evil things that they say about them.

And we’ve spent so much time trying to respond to every accusation. No, it’s not apartheid. No, it’s not this. Rather than exposing the mechanism that makes all these accusations of evil in order to reach the logical conclusion of “keep the world clean,” which has only ever been the ideology that preceded some of the most horrific acts.

Sruli Fruchter: Do you think peace between Israelis and Palestinians will happen within your lifetime?

Einat Wilf: It could be. They just need to stop being Palestinian-ists. They need to become Arabs, Muslims whose worldview is compatible with the idea of sovereign Jews.

Sruli Fruchter: Do you think that will happen?

Einat Wilf: It could. Homo sapiens have changed their views on other issues.

Sruli Fruchter: What do you think should happen with Gaza and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict after the war?

Einat Wilf: Well, this goes back to my claim that we should have defined the war differently. Because even on the goal of no Hamas, we haven’t achieved it. But fundamentally, I think we should break Gaza into a zone of war and a zone of peace.

A zone of war can be southern Gaza. We will not resupply it. Anyone who wants to continue to uphold the ideology of no Jewish state is welcome to live there. And we’re certainly under no obligation to resupply them while they continue to be our enemies.

And in the north, I think we should enable individual surrender. And I’ll call it the zone of peace and reconstruction. Every Palestinian who is no longer on the records of UNRWA as a refugee, who recognizes that they’re not a refugee from Palestine, that they want to live next to a Jewish state, that they understand they possess no such thing as a right of return, they’re welcome to live there and build their lives in peace. And if there’s no one who’s willing to say that, then it will be war.

Sruli Fruchter: So do you think Israel should occupy Gaza?

Einat Wilf: I don’t think we should occupy the people who refuse to surrender. The occupation in Germany and Japan was effective because it happened after surrender. We should only occupy areas where Palestinians surrender with the purpose of helping them become a different people, people who want to live next to the Jewish state. I don’t think we should occupy a population that refuses to surrender.

We should be at war with it. Occupation can happen after surrender.

Sruli Fruchter: So do you think that Israel should, meaning, from what you’re describing, it almost sounds as if, let’s say, I know the numbers probably may get them incorrectly because it’s confusing with who’s displaced where. But with the two million people in Gaza, if, let’s say, split in the middle, a million are like, we’ll go to that peace zone and a million are like—

Einat Wilf: No, no, no, no. Everyone stays in the war zone and individually they go to the peace zone, one by one.

Sruli Fruchter: So if theoretically a million people are still in the war zone, then it should be a war against the million Palestinians in Gaza, in that war zone.

Einat Wilf: Until they surrender, individually or collectively, yes.

Sruli Fruchter: Is Israel properly handling the Iranian threat?

Einat Wilf: I’ll say this.

I’m no expert on Iran’s military capabilities, where it stands. Maybe we have an opportunity now that we should make use of. That’s not my expertise. What I think we should have emphasized is two things.

The first is look at the last century of who supported Palestinian-ism. Because Palestinian-ism has always been the complete and total rejection of a Jewish state, it was supported by every anti-Jewish power for the last century. In the 30s and 40s, it was the Nazis. With lasting implications, people don’t realize that Hamas’ ideology is half Nazi, half Islamist.

There’s been some great scholarship done on that by Jeffrey Herf and Matthias Küntzel. Today, such an inconvenient fact that people like to pretend that Hitler and the Mufti just had lunch once, rather than acknowledge that this was an ongoing collaboration with the same goals and the same ideology. And the Nazis were defeated. And then the pan-Arabists turned Palestinian-ism into their secular ideology, literally creating the PLO.

And then the pan-Arabists are defeated. And then the Soviets come in. And then the Soviets are defeated in a Cold War. And after a short lull of the end of history, the Iranians become the main sponsors of Palestinian-ism.

So the good news in all of that is I can say with a fairly high level of confidence that the Mullah and Ayatollah regime will find itself in the same dustbin of history as the Nazis, the pan-Arabists, and the Soviets. Hopefully in a Cold War. That would be the better way for that to happen. And I’m not making some religious argument here.

It’s a sociological one. Societies that became obsessed with anti-Zionism, which is, again, merely a mark and a respectable mask for antisemitism, are always failed societies. Anti-Zionism, to use the language of the incoming president, is the ideology of losers. It’s the ideology of societies that do not solve problems but just try to blame the Jews for the problems.

So I think it’s fairly safe to say that this will be the outcome. I hope it will be in a cold war. My deep concern is how much damage they will cause to the Jews before they head to the dustbin of history. Because the Nazis, the pan-Arabists, the Soviets, they caused a lot of damage before they were gone.

And the question whether the Iranians are past the peak of the damage or before. And I think that’s key to what we should have emphasized. We should have emphasized the nature of the regime as the heir to the Nazis, the pan-Arabists, the Soviets. We should have emphasized, you know, people talk about the Israeli-Iran conflict.

There’s a conflict there. There’s no conflict. Iran’s position is death to Israel. That’s not a negotiable demand.

There’s no conflict here about three islands that, you know, who owns them, you know, an oil well. No, their view is death to Israel. It’s not a negotiable demand. So the conflict is us trying to stay alive.

And I think that’s what we should have emphasized more, that the problem here too is the ideology.

Sruli Fruchter: Where do you identify on Israel’s political and religious spectrum? And do you have any friends on the quote-unquote other side?

Einat Wilf: I define myself very much on the left, very secular. I call myself a devout atheist, very committed to secular Zionism.

Sruli Fruchter: And do you have friends on the other side?

Einat Wilf: Yes.

Sruli Fruchter: I am really curious that you identify as someone part of the Israeli left, because from our conversation, it doesn’t really seem like much of— aside from the secularism, much of anything in your political views align with the Israeli left, specifically in your views of the Palestinians. I’m not looking to get into the—which I know would be a much larger discussion, and it could itself be a podcast series on Palestinian identity and the history of that, but more so on the treatment of Palestinians and the future for Palestinians. Do you see that at all? Do you see the tension I’m referring to?

Einat Wilf: For me, it’s all empirical. I’m very much on the left in the sense that I want the homo sapiens that now go by the name Palestinians to enjoy sovereignty, dignity, freedom.

I just understand that the path to that is for them to let go of the ideology that for centuries has bound them to the destruction of the Jewish state.

Sruli Fruchter: But also of their identity as Palestinians.

Einat Wilf: That’s their identity. There’s no other identity.

Sruli Fruchter: What you said before was that to see themselves as Arabs, which I understood to mean as Arabs as opposed to being Palestinians.

Einat Wilf: Well, Palestinians means obsessed with the nonexistence of a Jewish state. There’s no other meaning for that term.

Sruli Fruchter: Why isn’t it Arabs who were indigenous or indigenous or living in this region?

Einat Wilf: Then they would be called Arabs, you could call them.

The day that they will go back to being called like Gazan Arabs or Shechem Arabs.

Sruli Fruchter: Isn’t people say Palestinian Arabs?

Einat Wilf: No. Not a lot of people are aware that if you look at the mandate for the establishment of a Jewish state, it includes the following language. Recognizing the historical connection between the Jewish people with Palestine.

The reason is that a hundred years ago, everyone knew that Palestine was merely the colonial, Roman, European, and Christian name given to the geography where the Jewish kingdoms once stood. The name for the Holy Land. The association with Jews was immediate. This is why a unanimous decision talks about the historical connection of the Jews with Palestine.

And then it uses language that did not exist in any of the other mandates to say that this historical connection is therefore the grounds for reconstituting. Meaning it was understood that in being in Palestine, the Jews were rebuilding, reconstituting an ancient homeland. Now in 1948, when the Jews finally are able to establish their sovereign state, they do what every self-respecting indigenous people did when they were finally home and the colonial yoke was gone, which is call themselves by their historical name, Israel. So now the name Palestine is held dangling.

So the Arabs, which again you will see the data until then, they’re called Arabs, hijacked the name Palestine beginning in the 60s to create this Palestinian identity, which is united by one thing and one thing only, the complete erasure, rejection of the Jewish right to self-determination in the land. Thereby creating this notion of Palestine for Palestinians, completely erasing and superimposing the notion of an exclusive Arab ideal. So the Arabs of the land, once they let go of Palestinian-ism, they will probably no longer go by that name because that name reflects the rejection of Jewish sovereignty. A colleague of mine recently wrote a nice little thought experiment.

He called it Levantia. He even kind of created a flag for it. And he said the day that the Arabs between the river and the sea no longer devote themselves to the destruction of the Jewish state, they will probably want a different name than Palestinian, which reflects the erasure of the Jewish connection. And he suggested Levantia, that they should state be called Levantia.

So I’m more than happy for a Levantia to emerge. I’m more than happy for the Arabs to be sovereign in a state of their own where they are no longer obsessed with the destruction of a Jewish state. I don’t have, let’s say, a religious notion that, you know, this only has to be exclusively all of it our land. It’s more important for me that the Jews be sovereign than to control every square inch mentioned in the Bible.

But it is very important for me that our enemies no longer be our enemies.

Sruli Fruchter: It’s for our last question. I know it’s been 18, but there have been a lot of follow-ups. That’s been probably a little longer if you’re keeping count.

Do you have more hope or fear for Israel and the Jewish people?

Einat Wilf: Depends on the days, seriously. Today is a tough day. Today some people sent me some material about the deep Muslim aversion to the idea of Jews as equals. And, you know, sometimes I struggle to hold on to hope for the possibility of change.

But sometimes I’m overwhelmed. That’s why I start by saying that I’m overwhelmed. Sometimes I’m overwhelmed by the scale of the animosity, the hatred. Not just the scale, not the fact that there are billions of people who are engaged in it, and that goes back to the numbers, but the fact that it goes so deep, that the idea that Jews cannot have power is by now a nearly two-millennia idea.

That the idea in the Muslim world that Jews cannot be equal is more than a millennia-old idea. So, yeah, I struggle to, I mean, on the one hand, homo sapiens are capable of change. And we even hold ideas that we didn’t hold 20 years ago and we look at people who held them 20 years ago as backward. So homo sapiens are people very capable of changing ideas, identities, ideologies.

But sometimes I’m overwhelmed by the possibility that there’s a Jewish exception almost. That, you know, this animosity will ebb and flow and we can just hope to live through the eras where it’s not as intense. But when you combine it with new weapons, new technologies, I do sometimes wonder if some people will ultimately have the means to achieve their utopian goal of keeping the world clean and putting the Star of David in a trash bin.

Sruli Fruchter: All right, Einat, well, thank you so much for answering our 18 questions.

How was this for you?

Einat Wilf: Fine. Sorry.

Sruli Fruchter: Okay, great. This was such an amazing interview with Einat.

I had a really great time probing deeper into her views and really trying to understand how she sees Israel and all of its many facets. I hope you enjoyed. And as usual, if you have questions you want us to ask or guests that you want us to feature, shoot us an email at info@18Forty.org. And a special thank you to our friends Gilad Browstein for editing the podcast and not Josh, but his friend Eitan, whose last name I am forgetting, for videoing the episode, which you can find on YouTube.

So until next time, keep questioning and keep thinking.

This transcript was produced by Sofer.AI.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Julia Senkfor & Cameron Berg: Does AI Have an Antisemitism Problem?

How can our generation understanding mysticism, philosophy, and suffering in today’s chaotic world?

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

What Garry Shandling’s Jewish Comedy Teaches About Purim

David Bashevkin speaks about the late, great comedian Garry Shalndling in honor of his 10th yahrzeit, which is this Purim.

podcast

Aaron Kotler: Inside the Lakewood Yeshiva

We speak with Rabbi Aaron Kotler about the beginnings of the American yeshiva world.

podcast

Yehuda Geberer: What’s the History of the American Yeshiva World?

We speak with Yehuda Geberer about the history of the yeshiva world.

podcast

Alex Edelman: Taking Comedy Seriously: Purim

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David is joined by comedian Alex Edelman for a special Purim discussion exploring the place of humor and levity in a world that often demands our solemnity.

podcast

Pawel Maciejko: Sabbateanism and the Roots of Secular Judaism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to historian and professor Pawel Maciejko about the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, Sabbateanism, and the roots of Jewish secularism.

podcast

The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

podcast

Micah Goodman: ‘I don’t want Gaza to become our Vietnam’

Micah Goodman doesn’t think Palestinian-Israeli peace will happen within his lifetime. But he’s still a hopeful person.

podcast

Anshel Pfeffer: ‘The idea that you’ll obliterate Hamas is as realistic as wanting to obliterate Chabad’

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu did not surprise Anshel Pfeffer over the last 17 months of war—and that’s the most disappointing part.

podcast

On Loss: A Spouse

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Josh Grajower – rabbi and educator – about the loss of his wife, as well as the loss that Tisha B’Av represents for the Jewish People.

podcast

Bruce Feiler: The Stories That Bind Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to author Bruce Feiler about family narratives.

podcast

When A Child Intermarries

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to a son who almost intermarried, the mother of a daughter who married a non-Jew, and Huvi and Brian, a couple whose intermarriage turned into a Jewish marriage—about intergenerational divergence in the context of intermarriage.

podcast

Aliza and Ephraim Bulow: When A Spouse Loses Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Aliza and Ephraim Bulow, a married couple whose religious paths diverged over the course of their shared life.

podcast

Benny Morris: ‘We should have taken Rafah at the start’

Leading Israeli historian Benny Morris answers 18 questions on Israel, including Gaza, Palestinian-Israeli peace prospects, morality, and so much more.

podcast

Netta Barak-Corren: ‘I hope that Gaza will see a day when it is no longer ruled by Hamas’

Israel is facing several existential crises—at least three, by Netta Barak-Corren’s account.

podcast

Lizzy Savetsky: Becoming a Jewish Influencer and Israel Advocate

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Lizzy Savetsky, who went from a career in singing and fashion to being a Jewish activist and influencer, about her work advocating for Israel online.

podcast

Modi Rosenfeld: A Serious Conversation About Comedy

In this special Purim episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we bring you a recording from our live event with the comedian Modi, for our annual discussion on humor.

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

David Aaron: ‘I believe that the Divine is existence and infinitely more’

Rabbi David Aaron joins us to discuss ease, humanity, and the difference between men and women.

podcast

Yishai Fleisher: ‘Israel is not meant to be equal for all — it’s a nation-state’

Israel should prioritize its Jewish citizens, Yishai Fleisher says, because that’s what a nation-state does.

podcast

Ken Brodkin: A Shul Becomes Orthodox

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Ken Brodkin, rabbi of New Jersey’s Congregation B’nai Israel, about how he helped turn it into “the Orthodox synagogue for all Jews.”