This essay is the last in the author’s five-part series for 18Forty’s explorations of the origins of Judaism. The fourth can be found here. The entire series can be found compiled here.

Tanach is the origin story of the Jewish People. It chronicles the Israelites’ encounters with God, teaching the consequences of allegiance or disobedience to His commands. Epic showdowns pit prophets against kings: Natan the prophet confronts King David about his sin with Batsheva while Eliyahu bests the prophets of Baal assembled by King Achav. Tanach also teaches religious values and presents theological questions. We learn of Ruth and Naomi, devoted to each other in kindness, but also of Iyov, the man of faith who lost it all, and Yonah, who ran from God.

But missing from this origin story are central aspects of Jewish life today—the study of Torah and adherence to a detailed halachic system. Prophets call for repentance and justice for the widow and orphan, but never tell anyone to go learn more Torah. And no one in Tanach seems to be keeping halacha in a way that the modern Jew would recognize.

In the time of King Yoshiyahu, the people hadn’t offered the Pesach sacrifice since the days of the shoftim (judges) who ruled Israel hundreds of years earlier (Melachim 23:22). No one seems to have worried about keeping kosher until Daniel in Nevuchadnezzar’s palace during the Babylonian exile (Daniel 1:12). Worse, the prophet Yechezkel contradicts halachot in the Torah, implying that all kohanim can’t marry widows (a prohibition limited to the Kohen Gadol in Vayikra) and that only kohanim can’t eat torn animals, or tereifot (Yechezkel 44:22, 31).

At the commencement of the Second Temple period, Ezra tells the people to build and dwell in sukkot, something that the verse tells us had not been done since the days of Yehoshua, Moshe’s direct successor. The entire holiday of Sukkot appears to have been forgotten for generations. But matters get stranger. The people travel to all the towns proclaiming the following (Nechemiah 8:15):

צְאוּ הָהָר וְהָבִיאוּ עֲלֵי-זַיִת וַעֲלֵי-עֵץ שֶׁמֶן, וַעֲלֵי הֲדַס וַעֲלֵי תְמָרִים וַעֲלֵי עֵץ עָבֹת לַעֲשֹׂת סֻכֹּת, כַּכָּתוּב

“Go out to the mountains and bring leafy branches of olive trees, pine trees, myrtles (hadas), palms and [other] leafy trees (alei etz avot) to make booths, as it is written.”

Yes, you heard that right. The people build sukkot out of hadasim and aravot (called anaf etz avot in the Torah), which are among the Four Species. We wave the Four Species during hallel; we don’t build sukkot from them. So where did the tradition from Sinai go wrong? Why are the people of Ezra’s time doing something completely different than what we do today?

Of all the issues I’ve addressed in this series, several people have confided in me that the lack of halacha in early Judaism vexes them most. And that’s understandable. When it comes to questions of how much was transmitted at Sinai and how to square the existence of machloket with an Oral Torah, we’ve seen that there is a lot of wiggle room. Some among Chazal said that only general principles were given to Moshe, and several Rishonim relied upon Chazal’s authority to expand the Oral Torah as needed, which necessarily led to much debate about halacha. Last time we noted that the Netziv even suggested that the interpretive principles that ground the Oral Torah developed over time. But acknowledging Chazal’s authority to interpret the Torah won’t solve the basic historical conundrum: What happened to the Torah after it was given at Sinai? Halacha is nearly absent in Tanach and perhaps for some time beyond. So how can we draw a straight line between the era of our ancestors and our own?

In this final installment, I will sketch a path through this historical quagmire, guided by the writings of several 19th- and 20th-century thinkers. These thinkers, paying keen attention to the fundamental changes in the Jewish People’s relationship to God when they were exiled from the land of Israel, provide a theology for acknowledging halachic evolution—perhaps even revolution—between Tanach and now. I can’t guarantee this approach will work for everyone, but I hope it inspires further reflection.

Rav Kook: Halacha Was the Second Stage of God’s Plan

Last time, we saw that the Netziv acknowledged that halachic reasoning developed over time. In his introduction to a work called Ha’amek She’eila, he further suggests that in the First Temple era, halachic rulings were based either on received traditions or were ad hoc and prophetically inspired. In later periods, however, when divine inspiration and prophecy waned, halachic analysis became more systematic and rigorous.

Two essays by Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak ha-Kohen Kook (1865-1935), the great religious Zionist mystic and Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine at the turn of the 20th century, take the Netziv’s ideas further in a way that addresses our question. In le-Mahalach ha-Ideot be-Yisrael, Rav Kook writes that during the First Temple period, a Jew’s religious experience was centered on the palpable presence of God and the fulfillment of national goals, not individual mitzvah performance. But after exile, matters changed:

כל אותה הפרטיות המעשית—של שמירת תורה ומצוות ודקדוקיהן הפרטיים … ולא היתה נכרת ובולטת כלל בפני אורה הכללי הגדול של זו—האידיאה האלוקית הישראלית—כנר לפני אבוקה וכשרגא בטיהרא—היא החלה עתה בסלוקו של האור הכללי הגדול בימי הבית השני, להקבע ולהתבלט באפיה הפרטי המיוחד. אז באה תחת האידיאה האלוקית בעצם רוממותה, ועל ידי גניזתה של זו—תולדתה האידיאה הדתית

All of those practical details of keeping Torah and mitzvot, and care about the particulars … [that] were not recognizable [in the First Temple period] and did not protrude at all in the face of this great universal light—the Jewish Godly idea—like a lamp is outshone by a torch or a candle in broad daylight, began now, with the receding of the great universal light in the Second Temple period, to be established in their special individual character. When the Godly idea at its apex was hidden, the result was the religious idea.

Two pages earlier, he writes:

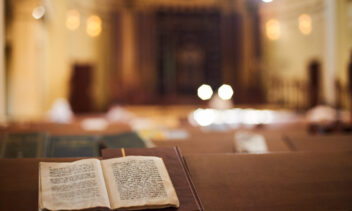

התכנסה האידיאה האלוקית בכל ימי הגלות בקן הקטן והדל, במקדש-מעט שבבתי-כנסיות ובתי-מדרשות, בחיי הבית והמשפחה הטהורים, ברשמי- שמירת דת ותורה.

The Godly idea in all the days of exile entered a small and low vessel, in the mikdash me’at of the synagogues and study halls, into home life and the purity of the family, in the confines of keeping the Torah and religion.

To Rav Kook, halacha’s lack of centrality in Tanach is not a bug, but a feature. During the First Temple period, the whole nation was suffused with the refulgent light of prophecy and was close to God. There was little place for a detailed system of halacha like we have today in such a rarefied atmosphere, especially because people could receive guidance directly from the prophets. Rav Kook believes that halacha existed in its general principles; there’s no reason to assume he would disagree with the approach of the Rambam and others that parts of the Oral Torah were revealed at Sinai and other parts developed later. Nevertheless, during the First Temple period, halacha’s details were outshone “like a candle in broad daylight (ke-shraga be-tihara).” It’s only when the Jews sinned and were exiled that God began to relate to them as individuals. With the light of prophecy dashed, each person now had to approach God through Torah and mitzvot. Halacha thus became far more central.

In another essay, Chacham Adif mi-Navi, Rav Kook explains that the detailed halachic system that developed was more successful than prophetic admonitions in bringing the Jewish nation toward God:

הנבואה ראתה את זרם הקלקלה הגדולה של עבודה-זרה בישראל ומחתה נגדו בכל עז … אלה המה המסתרים הצפונים מעין כל נביא וחוזה. המצות המעשיות כולן ופרטי הלכותיהן, בכל דיוקם הנמרץ … והוצריכה עבודת הכללים להמסר לנביאים ועבודת הפרטים לחכמים. וחכם עדיף מנביא, מה שלא עשתה הנבואה, בכלי מלחמתה החוצבים להבות אש לבער מישראל עבודת אלילים ולשרש אחרי עיקרי ההשפלות היותר הגרועות של עשק וחמס … עשו החכמים בהרחבת התורה, בהעמדת תלמידים הרבה ובשנון החקים הפרטיים ותולדותיהם … במשך הזמן הרב נתגבר עסק החכמים על עסק הנביאים והנבואה נסתלקה

Prophecy beheld the perverse stream of idolatry in Israel and powerfully protested against it … Hidden from the prophetic, visionary eye are all the practical mitzvot with the meticulous precision of their detailed laws. … It was thus necessary to assign to the prophets the task of generalities, and to the Sages the task of particulars. “A sage is superior to a prophet” [Bava Batra 12a]; that which prophecy did not accomplish with its fiery arsenal—namely to purge Israel of idolatry and to uproot the worst degradations of oppression … the Sages accomplished through the expansion of Torah, by raising up many students and by constant review of particular rules and their applications. … In the course of time, the work of the Sages superseded the work of the prophets, and prophecy ceased.

In prophetic times, halacha was on the sidelines due to the people’s high spiritual level and direct access to prophets. But when prophecy ended (notably, it had failed to root out idolatry), halacha with all its details became essential.

In these essays, Rav Kook acknowledges the gap between Tanach and our times. But he suggests that this gap is less troubling when we understand that God guides history. God ensured that the Oral Torah, with its attention to and expansion of halachic observance, began to flourish when its time was ripe. Prophecy had its day. Now it’s halacha’s turn.

Rav Tzadok: Oral Torah Was Our (Human) Response To Exile

Our second thinker, Rabbi Tzadok ha-Kohen Rabinowitz (1823-1900), was a Litvak turned Chasid who wrote several significant works and had a penchant for out-of-the-box ideas. His writings about the disconnect between Tanach and our times are similar to Rav Kook’s and help us better understand the development of the Oral Torah as an unfolding human process guided from above.

Like Rav Kook, Rav Tzadok distinguishes the eras of prophecy and halacha. In his book Resisei Layla, Rav Tzadok explains that when people could go to prophets for religious guidance, there was less need for the Oral Torah:

וזהו כל חכמת תושבע”פ להשיג האמת מצד האופל והעלם. וזהו בזמן ההעלם אבל בזמן שהיה השראת השכינה בישראל לא היו נכנסים להשגות של מחשכים כלל כי היה אז כל ההנהגה ע”פ נבואה דהיו נביאים כפלים כיוצאי מצרים

All the wisdom of Oral Torah is to apprehend truth from darkness and hiddenness. And that is in a time of hiddenness, but when the Divine Presence rested on Israel, they did not condescend to perception through darkness at all, for all guidance was through prophecy. For the [number of] prophets were twice that [of the Jews] who left Egypt.

Yet matters changed in exile:

וכן בגלות נשכח לגמרי התורה מהם בכלל האומה עד שמצאו כתוב לעשות סוכות ולא ידעו מזה. ואע”פ שלבבם נכון עם ה ביותר מ”מ עסק התורה היה שם בבחינת שינה והעלם … ומהם והלאה שייך הקבלה פה אל פה

And so in exile the Torah was completely forgotten among the nation to the point where they saw it written to make Sukkot and they knew nothing of it [Nechemiah 8:17]. Even though their hearts were faithful to God, nonetheless the study of Torah was as though in hibernation. … [30 pages later] And from then on the Oral Torah became relevant.

For Rav Tzadok, the flowering of the Oral Torah was historically contingent. It is also unequivocally a human endeavor. In Kometz ha-Mincha he writes:

ותושבע”פ היא מה שחדשו חכמי ישראל וכנ”י ע”י השגת לבם ומוחם מרצון השי”ת

Oral Torah is what the sages of Israel and the people of Israel innovated by their own perception of heart and mind of the will of God.

But if the Oral Torah is a human innovation, in what way does Rav Tzadok understand it as stemming from Sinai? In Likkutei Ma’amarim, he explains that the Oral Torah is latent in the Written Torah, waiting for the right generation to reveal it:

וכך התורה שבכתב היא כוללת בהעלם כל מיני חכמה … שכל מין חכמה דאמרי אינשי רק שהוא חכמה אמיתית ושפת אמת היא רמוזה בתורה אבל הכל ברמז והעלם רק אח”כ בהמשך הדורות הוא יוצא לאור ע”י חכמי דור ודור ודורשיו וע”י כל הנפשות פרטיות אשר כל אחד מחדש דבר חכמה אשר אליה הוכן בפרט. וזהו הנקרא תורה שבע”פ שהוא מה שחדשו סופרים ונובעים מליבות בני ישראל

The Written Torah includes in hidden form all types of wisdom … [Thus,] all types of wisdom uttered by people—so long as they are true—are hinted at in the Torah, but all are hidden in hints, and only in the course of the generations are they brought to light by the sages of each generation and its interpreters and through each individual soul which reveals the innovations in Torah that have been prepared for it. This is called “Oral Torah,” which is what the Sages innovate and which flows from the hearts of Israel.

Rav Tzadok believes that the Oral Torah is revealed progressively. In the time of Tanach, halacha was dormant. Over time, the Jewish people and their Sages brought the latent Oral Torah to light.

Like Rav Kook, Rav Tzadok sees a divine plan at work in the Oral Torah’s move from the sidelines to dominance. But more so than Rav Kook, Rav Tzadok stresses the role of human beings in revealing the Oral Torah through creative interpretation. Revelation is a divine-human partnership—not only top-down but also bottom-up, from the Jewish People back to God. Rav Tzadok thus links Chazal’s role as curators and creators of the Oral Torah with the notion that God intended the Oral Torah to be revealed piecemeal through history.

The Oral Torah In History

I believe that Rav Kook and Rav Tzadok’s theological account of the rise of the Oral Torah and the flowering of halachic Judaism provides a way to harmonize a traditional religious viewpoint with historical conclusions about the gradual development of rabbinic Judaism. It also provides a powerful religious message about the value of the Oral Torah.

One might put it in these terms: Exile and the end of prophecy ruptured and irrevocably altered the bond between God and the Jews. The Oral Torah was the attempt of a battered nation to reconstruct that relationship. In one of his essays on the Haggadah (see pp. 14-15 here), Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, of blessed memory, calls this shift “one of the great, if quiet, dramas of history.” It is after the fall of the First Temple that “the study of Torah replaced prophecy,” and “a succession of scribes, scholars, and sages began to reshape Israel from the people of the land to the people of the book.” Only through the Oral Torah did the Jewish people survive.

I find it particularly remarkable that in Rav Kook and Rav Tzadok’s vision, the revelation of the Oral Torah takes place within history, not outside of it. Recall that Geiger challenged the Oral Torah as a corruption of the Written Torah and the ethical monotheism of the prophets. Some Orthodox defenders responded by rejecting history’s role in the Oral Torah’s development. Rav Hirsch doubled down on its Sinaitic pedigree. The Malbim tried to ground the Oral Torah in eternal principles of language. Rav Kook and Rav Tzadok, on the other hand, acknowledge, like Geiger, that the Oral Torah emerged in history. Yet they suggest that history is not corrupting, but sanctifying. It is the arena upon which the Jewish people turned over a new leaf in their relationship with God.

Rav Hutner: God Wants Our Imperfect Torah

Rav Kook and Rav Tzadok help us explain the disconnect between the prophetic days of Tanach and our own more halachically conscious age. We could stop here, but there’s one lingering issue to address.

The Oral Torah often seems quite messy. It developed in a quintessentially human way—through arguments, splitting hairs, and the making of books without end. Halachic literature is littered with rejected opinions, customs that never took hold, and stringencies we might wish never caught on. Unlike an orderly top-down revelation, the bottom-up revelation of the Oral Torah is full of fractures, zigzags, and bends in the road.

This messiness can be troublesome because it contradicts how we might imagine a divine Torah should be. Geiger’s questions about irrationality still loom large. But I want to leave you with the following thought: Perhaps there is value to an imperfect and ever-expanding Oral Torah.

In an essay about Chanukah in Pachad Yitzchak, Rabbi Yitzchak Hutner (1906-1980), the rosh yeshiva in Yeshiva Rabbi Chaim Berlin in New York who was a student of Rav Kook and was influenced by Rav Tzadok, writes the following:

פעמים שביטולה של תורה זה הוא קיומה שנאמר אשר שברת יישר כוחך ששברת … למדים אנו מכאן חידוש נפלא כי אפשר לה לתורה שתתרבה על ידי שכחת התורה, עד כי באופן זה יתכן לקבל יישר כוח עבור השכחת התורה. ופוק חזי מה שאמרו חכמים כי שלש מאות הלכות נשתכחו בימי אבלו של משה והחזירום עתניאל בן קנז בפלפלו. והרי דברי תורה הללו של פלפול החזרת ההלכות, הם הם דברי תורה שנתרבו רק על ידי שכחת התורה. ולא עוד אלא שכל ענין המחלוקת בהלכה אינו אלא מצד שכחת התורה, ואף על פי כן הלא כך אמרו חכמים … אלו ואלו דברי אלוקים חיים. ונמצא דכל חילוקי דעות וחילופי שיטות הם הגדלת התורה והאדרתה הנולדות דוקא בכוחה של שכחת התורה

Sometimes one upholds the Torah by nullifying it—as it says: “[the luchot] that you broke” [Exodus 34:1], [and as the Gemara comments]: “Yasher koach for breaking them.” … We learn from here an astounding thing—that Torah can grow when it is forgotten, until it is possible in such a case to get a yasher koach for forgetting Torah. And go and see what the Sages said: 300 halachot were forgotten during the mourning period for Moshe and Otniel ben Kenaz returned them through his analysis [Temurah 16a]. And behold these Torah ideas that returned the halachot, they are words of Torah that grew only through forgetting the Torah. And what’s more, the entire notion of debate in halacha only came about through forgetting Torah, and even so the Sages say: … “These and these are the words of the Living God”; and we find that all differences of opinion are expansions and glorifications of Torah that came to be through the power of forgetting Torah.

Rav Hutner suggests that forgetting Torah is not a tragedy. To the contrary, it makes the Torah stronger, because in an attempt to recapture what was lost, there’s now more Torah.

It’s true that as First Temple Judaism evaporated, Chazal reconstructed the religion around a different axis, teasing latent ideas out of the Written Torah, leading to reams of machloket and uncertainty. But if we apply Rav Hutner’s framework, maybe that’s not a bad thing. God desires the back-and-forth of our debate, the glorious dialogue that attempts to catch sparks of the Divine.

So even if we can’t draw a straight line between Sinai and the here and now, perhaps we can celebrate the crooked path by which we have come to God. For God wants our Torah—which is just as much God’s Torah—as fractured, imperfect, and human as it may be.

Yosef Lindell is a practicing lawyer and one of the editors of the Lehrhaus living in Silver Spring, MD. He has a JD from NYU Law and an MA in Jewish history from Yeshiva University. Yosef’s published writing spans several genres, from science fiction to Jewish scholarship. His website is yoseflindell.wordpress.com.

—

Recommended Reading:

“R. Zadok HaKohen on the History of Halakha”

Yaakov Elman

In this article from the journal Tradition, which is available online for free, Dr. Elman, a longtime professor at Yeshiva University before his passing, explores Rav Tzadok’s novel view regarding the origins of the Oral Torah with citations to many of his works. He closes with a short discussion of Rav Hutner as well.