18Forty Magazine

LOSS

Feature

What did Rebbe Nachman, Rav Soloveitchik, Rav Hutner, and Rav Kook think was nechama? Rabbi Joey Rosenfeld tells us—and more.

- Joey Rosenfeld

Essay

Tears do not come easily to Tisha B’Av for us all. Rabbi Joshua Berman explores the reason why.

- Joshua Berman

Essay

If being lost means the inability to find one’s way or to miss something that cannot be recovered, then the death of a friend makes us disoriented and adrift.

- Erica Brown

Essay

If being lost means the inability to find one’s way or to miss something that cannot be recovered, then the death of a friend makes us disoriented and adrift.

- Erica Brown

Feature

What did Rebbe Nachman, Rav Soloveitchik, Rav Hutner, and Rav Kook think was nechama? Rabbi Joey Rosenfeld tells us—and more.

- Joey Rosenfeld

Essay

Tears do not come easily to Tisha B’Av for us all. Rabbi Joshua Berman explores the reason why.

- Joshua Berman

PODCASTS ON TESHUVA

Feature

A day for tears, yearning, mourning, and hope: 18Forty readers share what the Beit HaMikdash’s absence means for them today.

Poem

Renowned Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai offers profound thought in his poems, "Death of My Father" and "Forgetting Someone."

Book Excerpt

“I don’t know if my words could ever ease your pain,” Julie Yip-Williams writes in a letter to her two daughters. “But I would be remiss if I did not try.”

Interview

The strangeness of death, of loss, is that no matter how many books we read, how many philosophical discussions we have, how many psychologists we speak with, how many times we experience it, it will always be elusive—impossible to understand.

Interview

Human emotions are intense and, sometimes, incredibly painful. To avoid that hurt, we seek to escape into distraction to “take our mind off everything.” That's a mistake.

Feature

In one of 18Forty's Must Reads, Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg opens up about the loss of her husband.

Talmud Teaching

“During the course of a lifetime, virtually no one can avoid an encounter with death. Yet it is an experience for which one is rarely prepared.” — Dr. Emanuel Rackman

Feature

In one of 18Forty's Must Reads, Rabbi Shmuel Hain writes what a Marvel superhero and the ancient rabbis both knew: Grief is just love persevering.

Book Excerpt

Blaming someone for their pain—whether that's grief or some kind of interpersonal violence—is our go-to mechanism. How quick are we to demonize rather than empathize. How quick we are to move into debate, rather than hang out in the actual pain of the situation.

Feature

In one of 18Forty's Must Reads, Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin writes how, in Tractate Moed Katan, the Talmud teaches us the only life lesson we need.

Talmud Teaching

Our exile impacted God, Jewish society, and the Jewish People. The Talmud explains how.

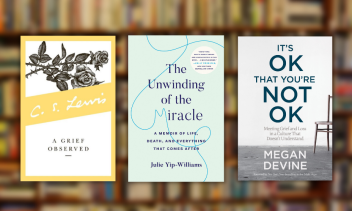

Book Excerpt

As we continue to expand our dictionary for our language of loss, 18Forty presents three books we find vital to the conversation.

Interview

It is Jerusalem, once a mother rejoicing with her children, who is grief-stricken, struggling to grasp the elusive understanding of loss. But she does not grieve alone.