I Read This Over Shabbos is a weekly newsletter about Jewish book culture, book recommendations, and modern ideas. Receive this free newsletter every week in your inbox by subscribing here. Questions, comments, or feedback? Email Rivka at Shabbosreads@18forty.org.

The period following Sukkot is known, at least here in Israel, as the dreaded “acharei hachagim”—after the holidays. Everything postponed for the past five weeks suddenly demands attention; there are no more excuses.

Contrary to popular belief, acharei hachagim doesn’t have to be terrible. The return to routine can be tough, yes, but there is beauty in normal life. I find comfort in waking up at the same time each day, eating sensible amounts of food, and getting just enough sleep—unlike during chag, when I eat too much and sleep even more.

What really carries me through this transition is a good book. It keeps me company throughout my day. I’ll read on the bus, before bed, and some more on the bus (I spend a lot of time there).

So I asked the 18Forty team what they’re reading this month, as we settle back into the rhythm of everyday life. As the sparkle of the chagim fades and the nights grow longer, may we find comfort in routine and ease in our day-to-day lives.

David Bashevkin — Founder

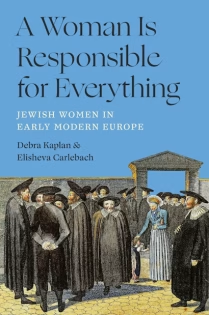

A Woman is Responsible for Everything by Debra Kaplan and Elisheva Carlebach

A Woman is Responsible for Everything: Jewish Women in Early Modern Europe by professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan is one of those rare works that reshapes not only what we know, but how we know. The book uncovers the oversized, often unacknowledged role of Jewish women who fashioned communal and religious life in early modern Europe—not only within the home, but in the broader networks of economy, ritual, and prayer. Beyond its rich archival research, the book’s images—culled from manuscripts, paintings, invitations, and portraits—animate this world, offering a visual tapestry of women’s multivalent presence in Jewish society.

On a personal note, I had the privilege of taking Professor Carlebach’s class on the Early Modern Period while completing my MA thesis, and she remains one of the most impactful teachers I’ve ever had. I still recall her unforgettable analogy for modernity: Before the modern era, thinkers would say a horse has 50 teeth because “50 is a very horselike number”; the moderns, by contrast, simply opened the horse’s mouth and counted. That shift—from theory to observation, from authority to agency—lies at the heart of both modernity and this book’s central argument: that Jewish women, too, were opening their own mouths, speaking, acting, and shaping the world anew.

Sruli Fruchter — Director of Operations

The Sabbath World by Judith Shulevitz

I started reading books in shul to compensate when the davening is just not doing it for me (not ideal, I know, but oh so productive). I seek books “religious” enough not to turn heads, but questionable enough to start conversations. Now, I’m reading The Sabbath World.

The Sabbath World is a spiritual biography not just of Judith Shulevitz, a conservative Jew and literary critic, but of a seeking Jew unlocking the Day of Rest’s ancient meaning in a chaotically modern world. Her sources are eclectic, her prose beautiful, and her vulnerability refreshing. As a lifelong Orthodox Jew, I love finding new ways to fall back into love with Jewish practices already integrated into my life. I am very grateful that Shulevitz—in all her messy, real humanity—is showing me the way this time around.

Denah Emerson — Podcast Editor

The Correspondent by Virginia Evans

The Correspondent by Virginia Evans is a thoughtful and beautifully written novel that explores themes of connection, memory, and self-reflection. Told through a series of letters written by the main character, Sybil, the story offers a unique look into her inner world as she navigates daily life and reflects on the past. The letter format gives the book a personal and intimate tone, making you feel like you’re reading someone’s private thoughts. Sybil is witty, sharp, and relatable, even as she deals with complex emotions and the changes that come with age. The writing is gentle but insightful, often touching on big ideas in quiet, meaningful ways. It’s a story about how we communicate with the people around us—and with ourselves—and how that can shift over time. While the pace is calm, the emotional depth keeps it engaging. Overall, it’s a quiet, reflective read that leaves a lasting impression.

Cody Fitzpatrick — Associate Editor

Sippurei Maasiyot: Rebbe Nachman’s Tales

On a recent episode of Haviv Rettig Gur’s podcast, the author and professor Dara Horn introduced me to the concept of Jewish “anti-literature.”

In non-Jewish stories, her idea goes, there are implicitly Christian emphases on characters “being saved” and “having epiphanies,” whereas Jewish literature has messy arcs and imperfect endings.

That’s not to say, however, that Jewish authors, even in the old days, were unaware of stories of the surrounding cultures. In fact, they were often reacting to them. She points out, for example, that Rebbe Nachman’s tales were clearly in conversation with the German and Russian folklore around him.

“His stories are rewritings of the Brothers Grimm,” Horn says, “but without the redemptive endings.”

She notes that Rebbe Nachman’s most famous story, “The Lost Princess,” about a viceroy who spends decades trying to find the princess, has a bizarre ending, which she paraphrases as: “Eventually he did free her, but I can’t tell you how.”

“For him this was a religious purpose because he’s writing about living in an unredeemed world,” Horn says of Rebbe Nachman. “For him this is a Kabbalistic idea that we’re living in this broken world and our job is to reconstruct it.”

It seems to me that, while a non-Jewish story can contain the entire arc of redemption in the tale of one person, a Jewish story presents just one piece of the puzzle. It demands that all of our stories contribute to the redemption narrative together.

Horn’s analysis inspired me to dive into Rebbe Nachman’s tales for myself. As I do so, I’m eager to see how my understanding of her thesis about Jewish “anti-literature” evolves.

Rivka Bennun Kay — Shabbos Reads Editor

The Empathy Exams by Leslie Jamison

After serving as a full-time bridesmaid at my friend’s wedding recently, she gifted me The Empathy Exams—a gesture I loved not just because brides should gift their friends, but because I adore when friends share books they believe will resonate.

The Empathy Exams is an award-winning essay collection by Leslie Jamison that probes the meaning and limits of empathy. A masterful storyteller, Jamison transforms niche subjects—a convention for people who self-diagnose with an unofficial disease, or an inhuman marathon through the Tennessee mountains—into explorations of pain, understanding, and shared humanity.

The book opens with a striking essay about her work as a medical actor—she performs symptoms and medical students diagnose her. They are graded not just for accuracy, but for empathy. Did they show compassion? Did they make the patient feel seen?

Across topics and styles, Jamison’s storytelling remains compelling and thought-provoking. Beyond making you want to turn the page, it makes you want to be a better person.

Gabriella Jacobs — Social Media Manager

The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R Tolkien

Every year during Sukkot, when the air turns crisp and the sukkah feels like the last haven between the holidays and the year ahead, I open The Lord of the Rings. Something about its beginning—the quiet of the Shire, the sense of setting out—matches the mood of the season. It’s become a kind of ritual for me, a book that carries me through the in-between: the slow shift from the intensity of Tishrei back into ordinary life.

Each year, the story feels a little different, and I notice new details. Tolkien, a devout Catholic who loved Hebrew and mythology, wrote a story that feels almost midrashic in its depth. While it may be confirmation bias, he also wrote a story in which I sometimes see a glimmer of Jewish thought and theme. Did you know Tolkien’s dwarves may be a stand-in for Jews? But more deeply, Tolkien’s moral vision, the fight against darkness not through power, but through faithfulness, humility, and the small acts of everyday people, reminds me of what I see as the Jewish vision of the good life: seeking satisfaction, fulfillment, and holiness not in grandeur, but in the details of daily living.