Reading Jewish History in the Parsha is a weekly newsletter from 18Forty, where guest writers contribute their insights on Jewish history and its connection to the weekly parsha. Receive this free newsletter every week in your inbox by subscribing here. Questions, comments, or feedback? Email Rivka Bennun Kay at Shabbosreads@18forty.org.

The following essay is taken from Rabbi Dr. Mordechai Schiffman’s forthcoming book, The Torah of Character: Psychological Growth Through the Weekly Parsha, available for preorder from Kodesh Press (with the discount code “character25”).

A running motif throughout Deuteronomy is Moses’ concern that the Israelites would be negatively influenced by the surrounding Canaanite culture. In Parshat Shoftim, Moses cautions them against following a subset of particularly spiritually and morally repugnant characters: augurs, soothsayers, diviners, sorcerers, spell-casters, and consulters of spirits, ghosts, and the dead. After listing the prohibitions, Moses concludes with a succinct positive formulation: “You must be tamim with the Lord your God” (Deut. 18:13). Translations of tamim vary and include “perfect,” “whole,” “complete,” and “wholehearted.” What exactly are the parameters and expectations of this abstract phrase? What, if any, relevance does it have in a society where the previously cited sins are less enticing than they once were?

Rashi provides a meaningful explanation, whose message transcends the ancient context. Fueled by an anxious compulsion to remove uncertainties, people sought answers from charismatic figures who were willing to forecast the future. The positive framing of being tamim, according to Rashi, is to encourage the Israelites to “put your hope in Him and do not attempt to investigate the future, but whatever it may be that comes upon you accept it wholeheartedly.” Rashi promotes the rabbinic version of what psychologist Tara Brach encourages in her book Radical Acceptance, “the willingness to experience ourselves and our life as they are.” We must trust and rely on God, without needing to know what will happen in the future.

Others interpret temimut as simplicity. This is not the same as naïveté. “It is not remaining oblivious to what has happened in the past or what may happen in the future,” writes Rabbi Dr. Benjamin Epstein. Aligned with the general thesis of his book Living in the Presence: A Jewish Mindfulness Guide for Everyday Life, temimut is described as “living with an innocence and humility that come from recognizing that all a person really has is right now.” Like Rashi, being tamim requires accepting every moment with simple faith instead of anxiously grasping for certainty through spiritually dangerous means.

But acceptance and simplicity do not intimate resignation or passivity. Our forefather Abraham was also commanded to be tamim (Gen. 17:1), but as Rabbi Jonathan Sacks notes, Abraham “is the father of faith, not as acceptance but as protest – protest at the flames that threaten the palace, the evil that threatens God’s gracious world.” It is up to us to emulate Abraham and “fight those flames by acts of justice and compassion that deny evil its victory and bring the world that is a little closer to the world that ought to be.” This model of tamim aligns well with acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which combines a mindful acceptance of the present with a deep commitment to living a life infused with meaningful action.

Rabbi Bahya ibn Pakuda, in his eleventh-century philosophical magnum opus Duties of the Heart, suggests that tamim should be understood as authenticity. The aim of Rabbi Bahya’s entire literary enterprise was to accentuate the inner life of the commandments. Tamim intimates the broad value in that “our exterior and interior should be equal and consistent in the service of God, so that the testimony of the heart, tongue, and limbs be alike, and that they support and confirm each other instead of differing and contradicting each other.” This quest for authenticity doesn’t necessarily demand “perfection” or “completeness,” but “wholeheartedness.” Even when broken and amidst feelings of despair, we genuinely turn to God with all our struggles. In the succinct and powerful formulation of the Kotzker Rebbe, “There is nothing as whole as a broken heart.”

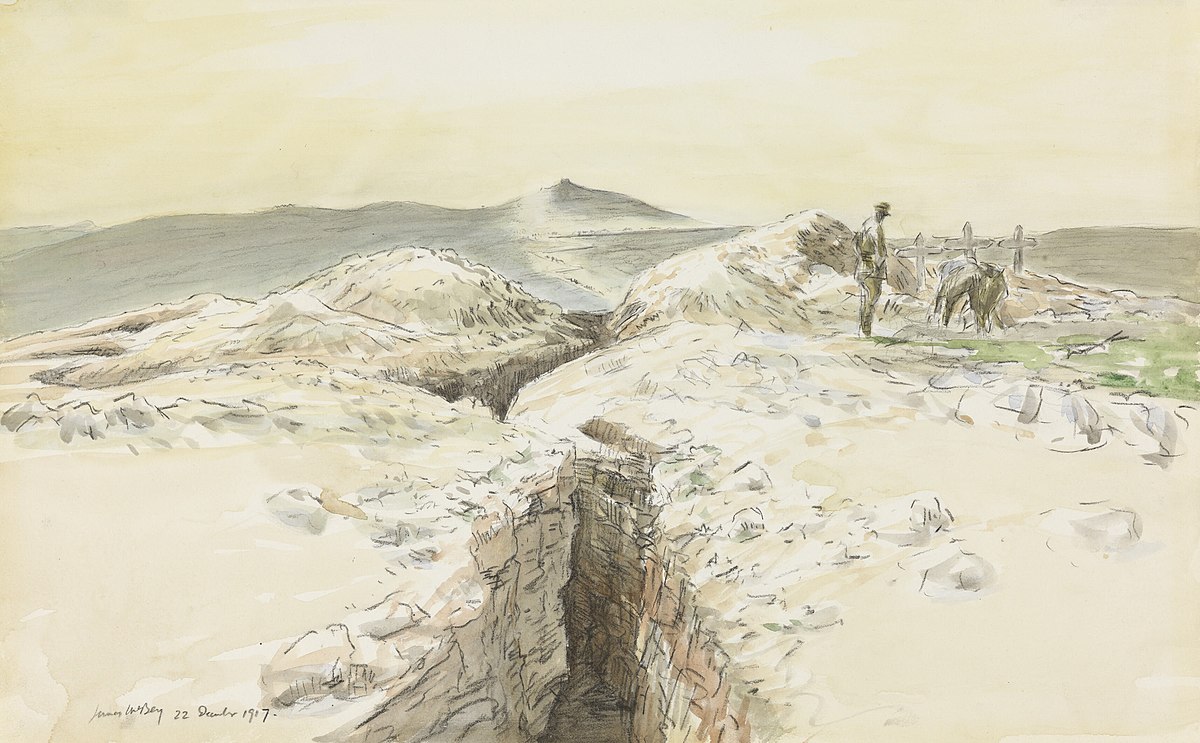

One year ago, in her powerful and moving eulogy for her son Hersh, Rachel Goldberg-Polin demonstrated the power of temimut in all its dimensions. In one particularly pertinent line, Rachel said, “It’s not that Hersh was perfect, but he was the perfect son for me. And I am so grateful to God, and I want to do hakarat hatov and thank God right now in front of all of you for giving me this magnificent present of my Hersh. For 23 years I was privileged to have the most stunning honor to be Hersh’s mama. I’ll take it and say thank you. I just wish it had been for longer.”

After living with grueling uncertainty for 330 days, Rachel turned to God in true authenticity and simplicity and was able to thank Him for the moments of subjective perfection she experienced with her son. Yet, as has been evident to all, Rachel’s temimut does not lead to passivity but to a heightened sense of action and protest against injustice. As we recently commemorated Hersh’s first yahrzeit, may Rachel’s example continue to inspire our own temimut, helping us to appreciate the power of each moment to fight the evil flames with justice and compassion.