Your 18Forty Parsha Guide is a weekly newsletter exploring five major takeaways from the weekly parsha. Receive this newsletter every week in your inbox by subscribing here. Questions or feedback? Email Rivka Bennun Kay at Shabbosreads@18forty.org.

Yaakov runs: not the measured stride of a traveler with provisions and plans, but flight. Someone whose world has collapsed. He has deceived his father, stolen his brother’s blessing, and now Esav wants him dead. His mother Rivka, the one person who understood him, sends him away. His brother Esav has explicitly vowed to kill him. He leaves Beer-sheba with nothing but terror and uncertainty.

When night falls, Yaakov stops because he can run no further. He takes a stone for a pillow—a sign of psychological collapse, not simple exhaustion. A stone for a pillow signals a mind too fractured to care about comfort.

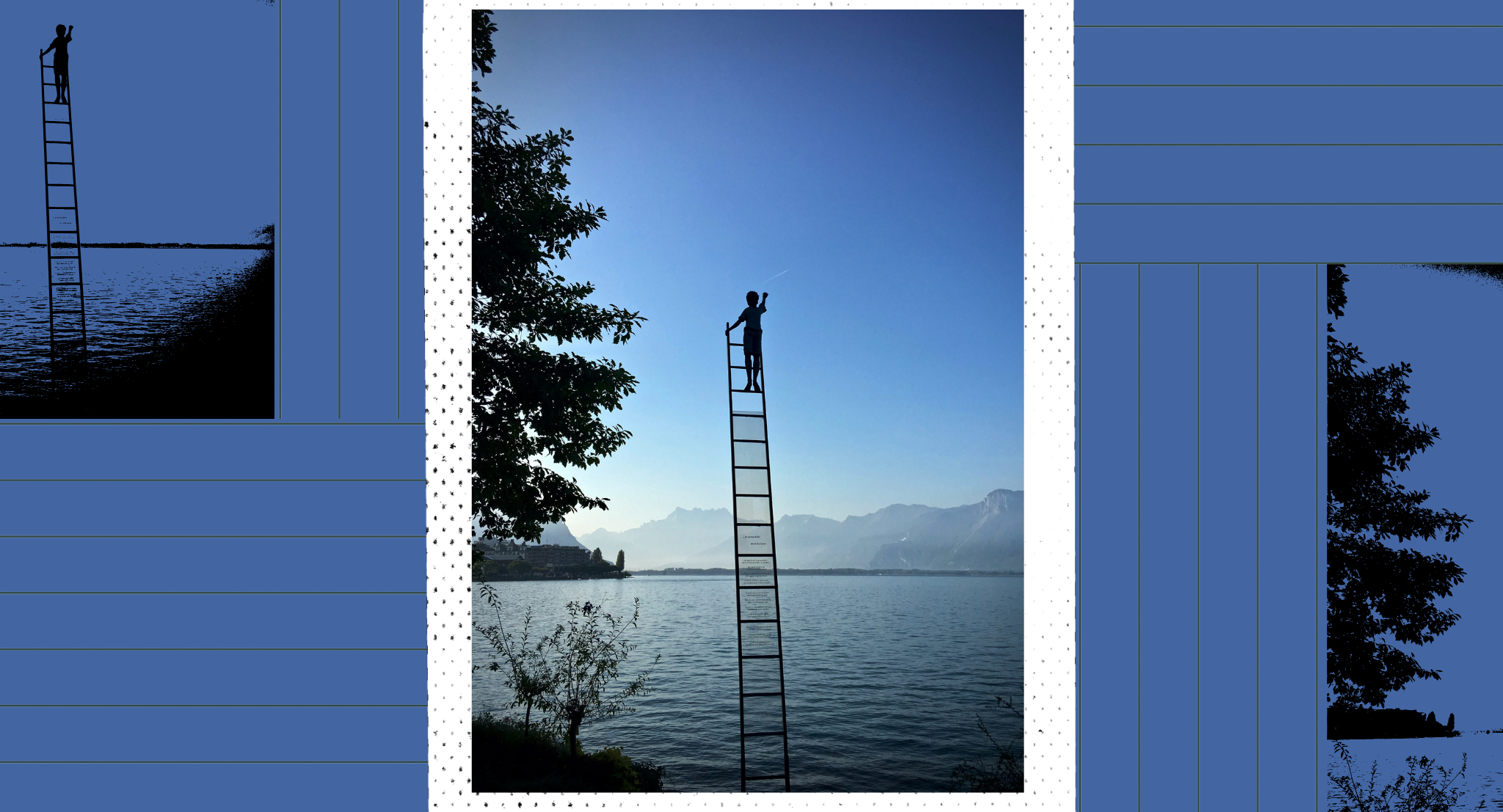

Then comes the dream. Angels ascending and descending a ladder that connects earth to heaven. God stands above it, promising presence, protection, and return. Yaakov wakes and says the most honest words in scripture: “Surely God is in this place, and I did not know it.”

This moment in Vayetzei speaks directly to anyone wrestling with anxiety, depression, or psychological crisis. Yaakov’s experience reveals something that ancient wisdom and modern psychology both confirm: Spiritual encounter doesn’t bypass mental struggle, it meets us within it. The sacred can appear when we’re falling apart, not because God rewards suffering, but because crisis can crack open defenses that usually keep us closed. For Yaakov, terror didn’t block the vision; it created unexpected openness. But this isn’t automatic: despair can also close us off entirely. What Yaakov discovers, and what matters most for anyone in crisis, is that you don’t need to find the grand meaning of your suffering right now; you just need to keep moving forward.

1. Anxiety Doesn’t Disqualify You From Encountering the Divine

Yaakov’s flight from home reveals classic symptoms of acute psychological distress. The text emphasizes Yaakov’s departure, and Rashi notes that the departure of a righteous person from a place leaves an impression. Specifically, the Shechina (Divine Presence) departs Beer-sheba with Yaakov. This context makes the Beit El encounter even more profound: the Presence had to be returned to Yaakov in his moment of collapse. God actively seeks out the broken person.

Previous 18Forty Podcast guest Rabbi Joey Rosenfeld explores how Jewish mysticism understands suffering as the entry point, not the barrier, to encountering meaning. The Baal HaTanya describes God choosing to build a palace in “the lowest imaginable place”: this broken world. The suffering isn’t incidental to spiritual encounter; it’s often the condition that makes us finally open to it.

What Yaakov experiences is what modern psychology calls the search for meaning. Viktor Frankl, who developed logotherapy, argues in Man’s Search for Meaning that finding meaning in suffering is humanity’s primary drive. Research in the Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy and a systematic review in Frontiers in Psychiatry demonstrate that meaning-based interventions significantly reduce depression and anxiety by helping people construct meaning from adversity. This is exactly what the Baal HaTanya describes as building that palace in the lowest place.

Yaakov doesn’t clean himself up before the dream comes. He doesn’t achieve emotional equilibrium or resolve his guilt. The vision arrives while he’s at his most broken, using a rock for a pillow in the wilderness. God doesn’t wait for our mental health to improve before being present, though we may not perceive that presence. Yaakov didn’t seek this vision: it arrived while he slept, terrified and broken. The divine presence can meet us in our panic attacks, our midnight anxieties, our stone-pillow moments. But perception of that presence isn’t guaranteed. It remains a gift, not an entitlement. What we can control is remaining open rather than closed, seeking rather than fleeing.

2. Why Spiritual Experiences Don’t “Fix” Psychological Wounds

Yaakov wakes up afraid: “How awesome is this place! This is none other than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven.” The Hebrew conveys both awe and terror.

Yaakov makes a conditional vow: “If God will be with me and will guard me on this way that I am going, and will give me bread to eat and clothes to wear, so that I return safely to my father’s house, then the LORD shall be my God.”

Modern readers often hear this “if” as transactional: worship in exchange for protection. But that reading misses what Yaakov is actually doing. He’s not bargaining for rewards. He’s expressing the reality that he can’t see evidence of divine presence yet, but he’s committing to maintain the relationship anyway. The “if” isn’t a condition for worship; it’s an acknowledgment that faith continues even when you can’t confirm the presence you’re seeking. This matters because transactional theology (righteousness earns protection) collapses when real life doesn’t cooperate. Yaakov models something different: remaining uncertain, yet choosing to move forward anyway.

A crucial distinction: You don’t need to discover the grand meaning of your suffering right now. Yaakov isn’t philosophizing about purpose while fleeing, he’s terrified and surviving. The Beit El vision doesn’t give him a neat explanation for why this happened; it gives him assurance he’s not abandoned and a promise when he can’t see forward. This describes immediate meaning: the sense of dignity and purpose found in choosing to act with integrity during crisis. Concretely, it’s the value in getting help, maintaining one practice, showing up for one person even when nothing makes sense.

This is what trauma psychology calls resilience: maintaining forward momentum despite ongoing symptoms. Dr. Rachel Yehuda’s 2014 research found that resilient people aren’t those who never develop symptoms. They’re those who maintain forward movement despite them.

Yaakov doesn’t leave Beit El “cured” of anxiety. He leaves with a different story about his anxiety: a framework that includes divine presence within psychological struggle. A meta-analysis in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology found that meaning-making interventions significantly improve outcomes in depression and anxiety, not by eliminating symptoms but by helping people construct meaningful narratives around their suffering.

The spiritual encounter doesn’t eliminate Yaakov’s distress. It gives him a way to carry it.

3. Recognizing the Sacred in Psychological Darkness

Yaakov’s statement upon waking, “Surely God is in this place, and I did not know it,” captures a truth about anxiety and depression: They distort perception so completely that we can be surrounded by presence and experience only absence. Anxiety insists we’re in constant danger. Depression declares nothing matters. These are totalizing worldviews that colonize consciousness.

Jewish mysticism and clinical psychology describe the same phenomenon in different vocabularies. The Kabbalists speak of hester panim (God’s hidden face) as the defining feature of exile. But crucially, hiddenness doesn’t mean absence. God remains present; our capacity to perceive becomes obscured. Modern psychology calls this cognitive distortion: the systematic way mental illness warps perception. Both frameworks recognize the same problem: the inability to perceive what is actually present.

Previous 18Forty Podcast guest Rav Moshe Weinberger describes how Chassidic thought addresses this struggle. Yiddishkeit isn’t supposed to cause suffering, but without proper keilim (the emotional capacity, interpretive frameworks, and support systems to hold religious demands), spiritual practice can feel oppressive rather than life-giving. Religious obligations meant to provide meaning become burdens when you lack the vessels to carry them.

Both spiritual practice and clinical therapy teach the same discipline: challenging distorted perception through consistent practice. Yaakov sees the same wilderness, still dangerous, still terrifying, but now recognizes divine presence within it. Depression therapy involves specific skills: writing down automatic thoughts and testing them against evidence, engaging in activities even when motivation is absent, deliberately noting moments that contradict the depression’s narrative.

In spiritual darkness, maintain practices like daily prayer, communal worship, and study even when they feel empty, trusting the framework provides structure when feeling has disappeared. This isn’t positive thinking that denies reality. It’s disciplined work distinguishing between what is actually present and what distorted perception claims. Yaakov’s statement, “God is in this place,” is both mystical affirmation and cognitive correction.

A systematic review in BMC Psychiatry found that spiritual practices help people cope with adversity by providing frameworks for interpreting difficult circumstances. Research in JAMA Psychiatry demonstrates that religious involvement correlates with reduced depression and anxiety largely because it provides cognitive frameworks for making sense of suffering. Both the mystical work of asserting presence and the therapeutic work of challenging cognitive distortions aim at the same goal: learning to perceive accurately despite what mental illness claims.

4. Psychological Struggle Births New Forms of Prayer

After the vision, Yaakov names the place Beit El (House of God) and makes his conditional vow. The Talmud teaches that Yaakov established Maariv (evening prayer) at this moment. The tradition links Yaakov specifically to evening prayer because evening represents hester: hiddenness, uncertainty, the time when vision fails. Avraham prayed at dawn, Yitzchak in the afternoon, but Yaakov’s prayer emerges from darkness and dread.

Yaakov’s prayer arises from psychological necessity, not divine command. It isn’t given at Sinai. It erupts from crisis: a man alone in the wilderness, terrified, needing some way to maintain connection when he can’t see or feel divine presence. This is why evening prayer has a unique status in Jewish law. The Talmud debates whether it’s obligation or optional, perhaps because what began as Jacob’s vulnerable human impulse only later became enshrined as communal practice.

Rav Judah Mischel explores this phenomenon: Authentic change emerges from crisis rather than calm decision-making. Real transformation happens when we’re pushed beyond usual coping mechanisms and forced to develop new practices. Both religious ritual and therapeutic coping skills often begin this way: born of desperate necessity before being refined into systematic practice.

This pattern appears throughout religious and clinical history. 12-step programs emerged from Bill W.’s desperate prayer in a hospital bed. Jon Kabat-Zinn founded Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) after systematizing his personal practice, which focused on stress management, into an eight-week clinical protocol. Yaakov’s evening prayer fits this pattern: practices born of psychological necessity becoming formalized rituals.

Yaakov’s prayer models what psychology calls affect regulation through consistent practice. He doesn’t pray despite his anxiety. The anxiety itself becomes the condition for maintaining ritual connection.

Modern trauma therapy teaches specific skills for “staying with” difficult emotions: name the emotion, notice where it sits in your body, observe the wave of emotion (techniques from Dialectical Behavior Therapy’s distress tolerance skills). Neuroscientist Jill Bolte Taylor discovered the “90-second rule.” When an emotion is triggered, the chemical cascade in your body peaks and begins to decline within 90 seconds if you don’t keep fueling it with additional thoughts. Grounding techniques like counting objects in the room help you stay present rather than spiraling. Then return to whatever practice provides structure. Yaakov’s evening prayer does this spiritually: facing darkness, naming it as real, maintaining the ritual of connection even when you feel nothing. Prayer becomes the vessel that holds the anxiety rather than eliminating it.

5. Living with Sacred Encounters and Ongoing Anxiety

After naming Beit El and making his vow, Yaakov continues his journey. He’ll face ongoing challenges: manipulation, loss, fear, and in the next parsha, Vayishlach, another terrifying divine encounter that leaves him physically injured and permanently renamed Yisrael. But he faces them.

This matters desperately for anyone dealing with ongoing mental health challenges. Religious communities often implicitly promise that sufficient faith or spiritual practice will “fix” psychological struggles. Some even suggest that persistent mental illness indicates insufficient faith. The Yaakov narrative demolishes this harmful theology. But the opposite error is equally dangerous: assuming that religious practice exacerbates mental health problems or that faith and therapy are incompatible.

The Torah shows that spiritual encounter doesn’t cure psychological wounds, but it can provide a framework for carrying them without being destroyed. Faith doesn’t replace treatment. It works alongside it.

Yaakov has a profound encounter at Beit El, receives divine promises, and then keeps walking into an uncertain future. He doesn’t wait to feel better or understand everything. He moves forward carrying both his terror and his encounter with God. When he faces his brother Esav years later, he’s still afraid, but he faces that fear.

The spiritual framework doesn’t eliminate distress. Here’s what it does provide: meaning (your suffering isn’t random or purposeless), structure (daily practices that hold you when feeling fails), community (people who show up), language (a vocabulary beyond just pathology), and hope (that recovery happens when you pursue treatment and do the work, and that your life holds deep meaning whether you’re struggling, healing, or thriving). These aren’t tradition-specific benefits. Research on post-traumatic growth published in Clinical Psychology Review shows that people across different backgrounds experience profound positive changes alongside ongoing distress when they can locate their suffering within a larger story.

In practice: Therapy addresses symptoms and teaches skills. Spiritual practice addresses meaning and provides structure. Both work together—medication alongside prayer practice that gives daily structure; CBT to challenge distorted thoughts alongside religious teaching about presence in darkness.

Yaakov’s journey traces this arc: spiritual encounter doesn’t end psychological struggle, but it provides a way to carry struggle without being crushed by it.

Questions for Reflection:

- What “stone pillow” moments have revealed something about your inner life or your relationship with God?

- Where might there be “God in this place, and I did not know it” in your life today?

- When has a moment of crisis pushed you to develop a new practice, habit, or form of prayer you might never have created otherwise?

This project is made possible with support from the Simchat Torah Challenge and UJA-Federation of New York. Learn more about the Simchat Torah Challenge and get involved at their website.