Your 18Forty Parsha Guide is a weekly newsletter exploring five major takeaways from the weekly parsha. Receive this newsletter every week in your inbox by subscribing here. Questions or feedback? Email Rivka Bennun Kay at Shabbosreads@18forty.org.

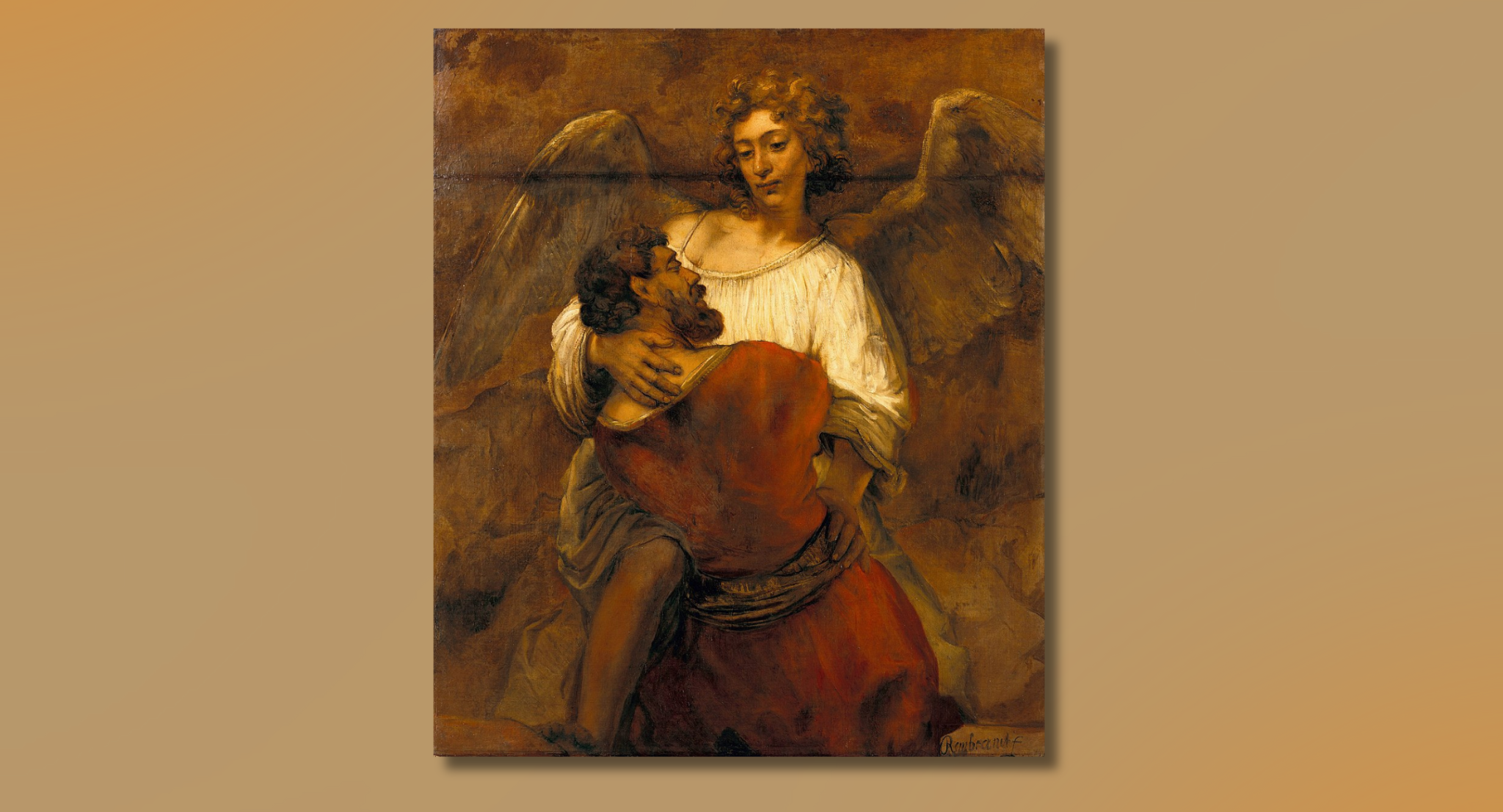

The night is dark. Yaakov is alone. A mysterious figure emerges and they grapple until dawn breaks. Yaakov’s hip is wrenched from its socket, yet he refuses to release his opponent until he receives a blessing. The figure renames him Yisrael, “one who struggles with God,” and vanishes as morning light floods the riverbank.

This scene from Parshat Vayishlach has haunted Jewish consciousness for millennia. After the Holocaust, this ancient wrestling match took on devastating new resonance. When Nazi Germany systematically murdered six million Jews and God seemed absent, the question shifted from “Why does Yaakov wrestle with God?” to “How can we?”

Both Yaakov’s struggle and post-Holocaust theology confront the same unbearable paradox: How do you maintain a relationship with a divine presence that permits catastrophic suffering? How do you demand blessing from a force that appears to have abandoned its covenant? As Dr. Rachel Yehuda explains when discussing intergenerational Holocaust trauma, the children of survivors often reported feeling like casualties of the Nazi genocide themselves. They inherited not just memories but the biological and psychological imprints of trauma their parents endured.

The wrestling at the Jabbok River offers a template for faith after the Nazi genocide of European Jewry. It shows us that struggling with God isn’t apostasy but authenticity, that injury doesn’t preclude blessing, and that a new identity forged through confrontation can emerge from the darkest night.

1. Wrestling Requires Presence: You Cannot Struggle with What You’ve Abandoned

Yaakov’s wrestling match begins with Genesis 32:25: “Jacob was left alone, and a man wrestled with him until the break of dawn.” The Hebrew word vaye’avek means they wrestled, they grappled, they remained locked in intimate combat.

This detail matters because wrestling demands proximity. You cannot grapple with something from a distance. You cannot struggle against an opponent who isn’t there. The very act of wrestling presumes engagement, even when that engagement feels adversarial.

The Choice After Auschwitz

Post-Holocaust theology faced a fundamental choice. Some concluded that after Auschwitz, God must be absent—either powerless, indifferent, or nonexistent. Others, drawing on the Yaakov narrative, insisted that struggle itself proves presence. To wrestle with God’s silence is still to wrestle with God.

Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits articulated this position in his influential Faith After the Holocaust. Berkovits argued that God’s hiddenness during the Nazi genocide (hester panim in Hebrew) was not absence but self-limitation, necessary for genuine human freedom. God’s apparent silence allows people to act as moral agents rather than puppets. History becomes humanity’s responsibility. The Holocaust represented the catastrophic cost of that freedom, but the alternative would be a world where human choices lack moral weight.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks developed a complementary theodicy based on divine self-limitation. In his faith lectures on creation, Rabbi Sacks addressed the question directly: “If God indeed created man and gave him free-will, does God intervene to stop him using his free-will or does He let him go his own sweet way? And if He does intervene, why didn’t He intervene in the Holocaust?”

Rabbi Sacks’ answer centered on the metaphor of parenthood. He quoted an American Jewish mother who said, “Now I find I can relate to the Almighty much better, because now I know what it is to create something that you can’t control.” God’s gift of human freedom necessitates non-intervention, even during atrocities. To intervene would violate the covenant of free will itself. The Germans chose to commit the Nazi genocide. God, having granted humanity moral agency, would be negating that gift by overriding their choices, however evil.

This theodicy doesn’t satisfy everyone. But it represents an attempt to maintain both theological commitment and historical honesty simultaneously. Many Holocaust survivors maintained Jewish practice after liberation. Their choice wasn’t based on receiving satisfying answers. It was based on recognizing that their identity as Israel, as God-wrestlers, meant engagement rather than abandonment defined their relationship to the divine.

2. Wrestling Leaves Marks: Blessing Arrives Through Wounding

“When he saw that he had not prevailed against him, he wrenched Jacob’s hip at its socket.” The injury was permanent. Verse 32 notes that “the children of Israel do not eat the thigh muscle that is on the socket of the hip to this day, because he struck Jacob’s hip socket.”

Traditional interpreters debate whether this encounter was literal or visionary. Maimonides understood Yaakov’s wrestling as prophetic vision rather than physical combat, yet the injury remained real—spiritual struggle manifesting in bodily form. This integration resonates with contemporary understanding of trauma. Just as Yaakov’s wrestling (whether with external divine messenger or internal crisis) left permanent physical marks, post-Holocaust psychological trauma leaves biological markers. Wrestling with God encompasses both external confrontation with historical evil and internal processing of faith, meaning, and inherited suffering. The wound isn’t purely physical or purely psychological. It’s integrated.

The wrestling match didn’t produce an unblemished victor. Yaakov received both blessing and injury. The transformation into Yisrael came with a lifelong limp. You cannot separate the wound from the identity change. They’re theologically inseparable.

Faith Marked by Trauma

Rabbanit Rachelle Fraenkel, whose son Naftali was murdered by terrorists in 2014, spoke about how trauma reshapes faith without destroying it. She describes faith after loss not as unchanged belief but as a transformed relationship, marked by questions that don’t disappear but become integrated into religious life itself.

Post-Holocaust theology mirrors this pattern. Faith after Auschwitz bears the scars of that encounter. Philosopher Emil Fackenheim, a concentration camp survivor who escaped from Sachsenhausen, formulated what he called the “614th commandment”: Jews are forbidden to grant Hitler posthumous victories. This meant Jews must survive as Jews, remember the victims, not despair of God or humanity, and work toward making the world a place of divine presence.

Fackenheim’s formulation acknowledges that post-Holocaust Jewish identity carries permanent marks. The covenant continues, but it’s wounded. Faith persists, but it’s scarred. Like Yaakov’s limp, this doesn’t represent failure but the cost of engagement. The Holocaust becomes part of Jewish identity without becoming its defining feature.

Rabbi Sacks, in his response to Fackenheim’s 614th commandment, argued that while Fackenheim was right about Jewish survival’s importance, “Jewish survival has religious significance after the Holocaust only because it had significance before the Holocaust.” The blessing predates the wound. The covenant predates Auschwitz. The Nazi genocide wounded but did not create Jewish identity. Jews don’t survive merely to spite Hitler. They survive because the wrestling match with God began at Sinai, continued through countless persecutions, and persists after the Nazi genocide as well.

3. Wrestling Changes Names: Identity Transformation Through Confrontation

“Your name shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have struggled with God and with humans and have prevailed.” The name Yisrael means “one who struggles with God.” Identity itself becomes defined by theological wrestling.

This transformation wasn’t metaphorical. Yaakov became Yisrael. His descendants inherited the name and the identity it represents. Every Jew carries the designation “one who struggles with God.”

The Necessity of Questioning

Rabbi Shalom Carmy explores how doubt and questioning function within Orthodox theology. He argues that faith incorporating doubt is more intellectually honest than faith that denies it. Religious existence includes wrestling with divine hiddenness, not just accepting it passively.

Post-Holocaust Judaism claimed this identity with new urgency. After the Nazi genocide of European Jewry, the question wasn’t whether Jews could question God. The question was whether they could maintain a relationship with God while carrying those questions. The name Yisrael answered that question. Struggling with God is the relationship.

Berkovits emphasizes this in Faith After the Holocaust. He insists that authentic post-Holocaust faith must ask the hardest questions without demanding impossible answers. He famously writes that contemporary Jews are “Job’s brothers,” meaning we didn’t experience the Holocaust directly, so our theological wrestling differs from survivors’ wrestling. But wrestling itself remains mandatory. To stop questioning would mean abandoning the covenant, not maintaining it.

Emil Fackenheim’s concept of “mending the world” (tikkun olam) after the Holocaust exemplifies this transformed identity. In his major work To Mend the World, Fackenheim argues that after the Nazi genocide shattered previous moral and philosophical categories, the task wasn’t to explain the Holocaust but to respond to it by rebuilding civilization’s broken foundations. The response defines the identity, just as Yaakov’s wrestling defines Israel.

4. Wrestling Happens in Darkness: Faith Functions Without Clarity

Genesis 32:25 specifies the timing: “Jacob was left alone, and a man wrestled with him until the break of dawn.” The entire encounter occurrs in darkness. Yaakov cannot see his opponent clearly. Only when dawn breaks does the figure disappear.

This darkness isn’t incidental. Wrestling with God happens precisely when clarity is absent. If Yaakov could see clearly, if he knew definitively he was grappling with the divine, the encounter would lose its theological force. The darkness creates the space for faith.

God’s Hiddenness During the Shoah

Elie Wiesel captures the theological crisis of divine hiddenness in the most powerful scene from his memoir Night. At Buna concentration camp, the SS hanged three prisoners, including a young boy, a pipel with “the face of a sad angel.” The two adults died quickly, but the child, too light for the rope to kill him instantly, hung between life and death for over half an hour. As the prisoners were forced to march past, a man behind Wiesel cried out, “Where is God now?”

Wiesel heard a voice within himself answer: “Where is He? Here He is. He is hanging here on this gallows.”

This scene represents wrestling with God in absolute darkness. Wiesel doesn’t conclude that God is dead or absent. He places God present in the suffering itself, present in incomprehensible ways that offer no comfort, no explanation, only the unbearable reality of divine hiddenness at its most extreme. The question “Where is God?” receives an answer, but the answer creates more theological anguish than resolution. This is faith in darkness without clarity.

Wiesel’s theology complements rather than contradicts the hester panim framework. God remains hidden from intervention (preserving human freedom, as Berkovits and Sacks argued), yet somehow present in solidarity with those who suffer. The hiddenness and the presence aren’t opposites but paradoxically simultaneous.

Yossi Klein Halevi discusses how Israeli society grapples with the memory of the Nazi genocide while building a vibrant Jewish state. He notes that Israeli Judaism often operates without neat theological answers, focusing instead on collective survival and meaning-making through action rather than explanation.

5. Wrestling Produces Blessing: Grace Emerges From Struggle

Genesis 32:30 culminates: “And he blessed him there.” After the injury, after the name change, after the darkness, blessing arrives. Yaakov doesn’t just survive the encounter. He’s transformed by it.

The blessing’s content remains unspecified in the text. But the name change itself functions as a blessing. Yisrael represents a more authentic identity than Yaakov. The struggle produced something Yaakov couldn’t have achieved through passive acceptance.

Continuing Jewish Life as Blessing

Post-Holocaust Jewish existence embodies this pattern. The mere fact that vibrant Jewish communities exist after the Nazi attempt at total annihilation represents a form of blessing wrested from catastrophe. This doesn’t minimize the horror. It acknowledges that Jewish response to the Holocaust includes building rather than only mourning.

Berkovits concludes Faith After the Holocaust by insisting that Jewish survival through history, including survival after the Nazi genocide, points toward meaning that transcends historical explanation. The fact that Jews continue wrestling with God after Auschwitz, rather than abandoning the covenant, represents a kind of blessing, however painful and complicated.

Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik offered perhaps the most powerful Orthodox theological framework for understanding blessing after catastrophe in his 1956 address Kol Dodi Dofek (“The Voice of My Beloved Knocks”). Delivered on Israel’s Independence Day, Rav Soloveitchik distinguishes between the knock of fate and the knock of destiny.

The knock of fate came during the Holocaust. Fate is existence as an object, passively suffering what history inflicts. Jews were thrust into suffering not by choice but by Nazi brutality. The Holocaust represented fate at its most catastrophic.

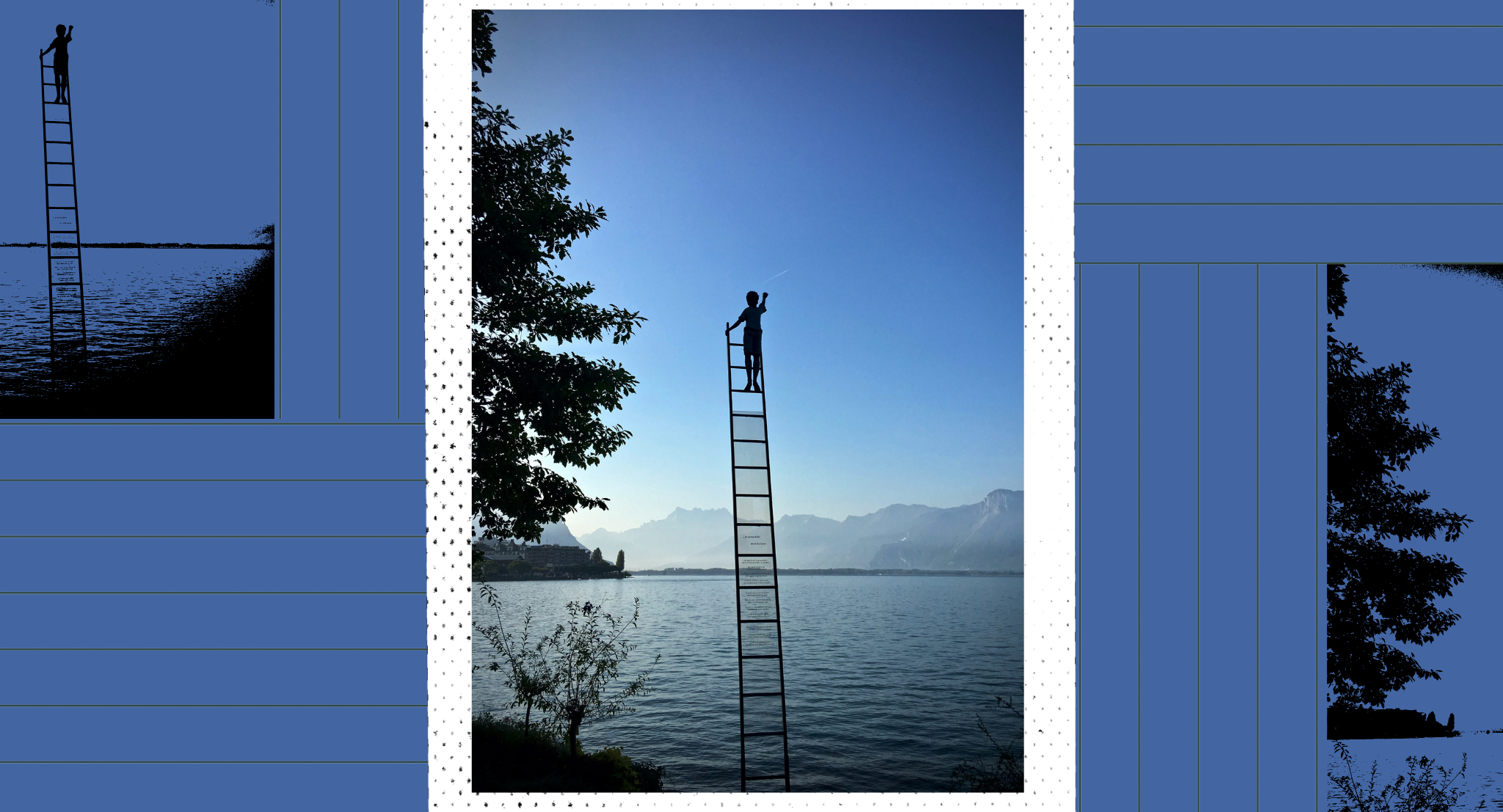

But after the knock of fate came the knock of destiny. Destiny is existence as a subject, actively choosing purpose and meaning. The establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 represented the knock of destiny, calling Jews to transform passive suffering into active historical responsibility. Rav Soloveitchik argues that the imperative is “to transform our existence from a causally determined, purely natural existence (fate) into an active, meaningful one suffused with a sense of purpose (destiny).”

This is the blessing wrested from darkness. Not that the Holocaust is redeemed, not that the six million are justified, but that Jewish response to catastrophe includes building rather than only mourning. The State of Israel, vibrant Jewish communities, families raised in tradition, all represent destiny answering fate.

Questions for Reflection:

- What does it mean to you to carry the name Yisrael—”one who struggles with God”?

- Is there a difference between questioning God and abandoning God? Where is that line for you?

- What would it mean to “refuse to let go until you receive a blessing”?

This project is made possible with support from the Simchat Torah Challenge and UJA-Federation of New York. Learn more about the Simchat Torah Challenge and get involved at their website.