I Read This Over Shabbos is a weekly newsletter from Rivka Bennun Kay about Jewish book culture, book recommendations, and modern ideas. Receive this free newsletter every week in your inbox by subscribing here. Questions, comments, or feedback? Email Rivka at Shabbosreads@18forty.org.

Whenever I tell someone I’m reading Amos Oz, the reaction is almost always, “Why? He’s so depressing.” Or, “Oz? He might be a good writer, but he’s practically anti-Zionist—you don’t actually agree with him, right?”

I think this says more about how Oz—who stood among Israel’s most influential authors and public intellectuals, and who was a lifelong labour Zionist—is misunderstood, than about the quality of his writing.

Among my peers, if they’ve heard of him at all, Amos Oz is often seen as either a pessimist or a political critic too sharp and scathing for comfort. They are missing the point of his novels entirely.

Oz once wrote:

My books are often seen as political statements, but they’re not. If I want to state something very directly—for example, that my government should go to the devil—then I’ll write an article or go on television and say, ‘Dear government, go to the devil.’ If I want to make a political statement, then I’ll write one. When the question is less simple—when within me I hear several points of view—then, perhaps, I write a novel. (Israel, Palestine, and Peace, 1994)

The questions Oz addresses in his novels are not simple, and they don’t have simple answers. That’s exactly what I love about his work. I often can’t even tell what his answer is, which I find increasingly rare in contemporary fiction. Through his novels, I can navigate and contemplate big ideas in all their complexity without feeling pushed one way or another: belief vs. doubt, love vs. disappointment, dream vs. disillusionment, ideas vs. reality. Big paradoxes like these weave through Oz’s work, and grappling with them was his real underlying “point” in writing.

Amos Oz has been a companion of mine since I made aliyah just over two years ago, at 19. In that time, I’ve slowly but surely made my way through several of his books, including A Perfect Peace, My Michael, Don’t Call It Night, and Judas, and I recently began reading what many call his masterpiece, A Tale of Love and Darkness.

Reading Oz has been a quiet education for me in adulthood and belonging in Israel. The tensions Oz probes across his writing are the same ones I’ve struggled with since making aliyah: identity, self perception, community, the gap between expectation and reality. For the past two years, I have endlessly tried to resolve these contradictions, and through Oz’s work I have explored different aspects of myself and my new surroundings.

Each book spoke to me in a different way—as a young person trying to find my place in the world, as an idealist learning to reconcile big dreams with reality, and as an olah chadasha still figuring out what it means to live here in Israel, in all the beauty, contradiction, and history that Israel contains.

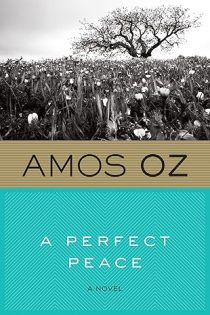

A Perfect Peace

I read A Perfect Peace during my first year at Tel Aviv University, four months after I moved to Israel. It was my first time outside the Anglo bubble of my Jerusalem seminary. I was still very much adjusting to life here, and to adulthood in general: Hebrew conversation, the tactlessness of Israeli culture, the absence of a support system or mentors, and the sense (especially after October 7) that everything was always slightly fraying at the edges.

A Perfect Peace takes place on a kibbutz in the early 1980s. Its young protagonist, Yonatan, is restless and idealistic. He’s the son of one of the founders, a man who built the kibbutz from scratch and sees it as a dream come true. But for Yonatan, the dream is suffocating. He longs for freedom, for a life that’s truly his own, yet every attempt to escape pulls him back to the same place.

Reading it, I felt a strange kinship with Yonatan. My own idealism—about making aliyah, about college, about the “deep meaning” I believed should accompany every decision—was beginning to hit the limits of real life. Classes, loneliness, and an inability to help Israel’s war effort to the extent I wanted to, or in the ways I idolized all chipped away at my romantic vision of what aliyah would be.

But in A Perfect Peace, Oz doesn’t treat accepting disillusionment as failure. Rather, it’s the moment when we stop living with deep and futile angst, and start adapting to reality. By the end, Yonatan, with some sadness, accepts that his dreams are wild and unattainable. This is what allows him to take genuine, realistic, steps toward living a meaningful life. For me, that meant letting go of the intense pressure to make every experience significant. I started to look instead for quieter forms of meaning, daily activities that could hold at least some of my idealism without breaking under its weight.

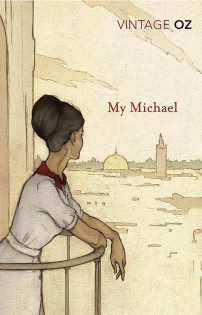

My Michael

I read My Michael when I moved to Herzliya, after beginning a nine-month stretch of long-distance with my now-fiancé. It was winter, damp and grey. My roommates were in miluim, the fledgling friendships I had created in my year in Tel Aviv had loosened, and I hadn’t yet invested energy in building a new community in Herzliya. I felt peripheral to every circle, an addendum and not a mainstay. In a way I had not felt since the very beginning of the war, I was truly alone.

My Michael is set in 1950s Jerusalem, and it follows Hannah Gonen, a young wife who becomes trapped inside her own isolation. Her husband, Michael, is gentle but emotionally unreachable. Her wild fantasies, both waking and dreaming, become her only escape, as she slips into deeper solitude and becomes increasingly unstable.

Oz’s Jerusalem in My Michael is a place of silence and isolation. The walls close in, the air feels stagnant; it feels like something is on the verge of explosion, but the simmering tension is never resolved. Reading it alone in my apartment, I felt an uncomfortable recognition. The monotony of university, the quiet nights, the sense that everyone else already had a community while I was still looking for one—Hannah’s restlessness felt very familiar.

What struck me most was Oz’s restraint. He never pities Hannah, never condemns her. He allows her loneliness, imagination, and goodness to coexist alongside her bad days and her better ones. That taught me something subtle but important about adulthood: sometimes you just have to let things be and trust that better days will come (and they have).

The biggest message I took away from that era of my aliyah, although Oz never spells it out directly, is that family and community really do matter more than almost anything else. They are worth investment, and it might mean enduring the space between belonging and solitude.

Judas

Judas was the Oz novel I struggled with most, and it’s when I began to understand my peers’ objections to Oz. It’s the story of Shmuel Ash, a young scholar in 1959 Jerusalem who takes a job caring for an elderly man and his mysterious daughter-in-law. By night, he studies the figure of Judas Iscariot, the ultimate betrayer of the Second Testament. He begins to ponder the nature of betrayal, oftentimes through questioning who “betrayed” the country of Israel during the era after its founding.

The book was dense, a bit too metaphorical for me to appreciate deeply, and it pushed a political agenda openly enough that I found myself resistant to its ideas, wary of being steered towards a particular conclusion, rather than invited to think. But I still gained a lot. By then, my life was stabilizing, and I was beginning to question my own particular “brand” of Zionism and my religious identity.

After a visit to my family in America, a few months surrounded by Tel Aviv University’s loud liberalism, and Shabbatot with more conservative friends in Gush Etzion and Jerusalem, all while the war dragged on, my head was a swirl of half-formed convictions, which I tested against every fully formed conviction that crossed my path.

Oz’s Judas contained half-formed convictions and fully formed convictions aplenty. When I read Oz’s explanation for how he writes novels in response to his hardest questions, I immediately thought of Judas, because even as the novel carries a clear political current, you can feel Oz’s own hesitation pulsing underneath.

That stretch of time was defined by trying to refine exactly what I believed, particularly about Israel and faith. Judas helped me take another step toward more certainty in what I did and didn’t hold to be true. But, it also moved me toward comfort with obscurity and grey areas. Like Oz himself, I learned to sit with uncertainty, and accept my lack of complete clarity.

Don’t Call It Night

I came to Don’t Call It Night when life finally felt a bit more steady. The long-distance stretch with my fiance was ending, my community had begun to take shape at long last, and the sharp edges of needing to “figure everything out” had thawed significantly.

Don’t Call It Night is set in a small desert town. Noa, a teacher in her forties, and her partner Theo, an older man, are trying to start a rehabilitation center after one of Noa’s students dies from a drug overdose. The project exposes “flaws” in their relationships: their differences, their pride, their quiet fatigue with life. Nothing works out for the couple quite as planned, yet there’s a strange serenity in their failure. When Oz describes their shortcomings, it is with tenderness, and when the couple see each other in all their insufficiencies, they embrace and receive each other warmly.

If Judas is Oz’s most political book, Don’t Call It Night is his most light-handed. The desert landscape, and the small town therein, have no real ideology. All that exists there are people doing their best with what they have. I loved that. It matched the stage of life I feel I am entering. I am no longer so focused on chasing perfection or community, or trying desperately to distill my own beliefs. I’m mostly just learning to tend to the small, good things and move forward with satisfaction, and excitement for what’s next. Oz would call that the opposite of fanaticism: not indifference, but proportion. To live and love quietly, with no illusions, and still to try.

A Tale of Love and Darkness

I recently began A Tale of Love and Darkness, Oz’s memoir, and it feels right that this book finds me back in Jerusalem, at the beginning of winter, where I started my aliyah journey.

The memoir opens in a cramped apartment in Jerusalem of the 1940s, where his parents, European intellectuals, fill the rooms with books and unspoken desires and longing. His mother’s depression hangs over the story like a shadow that will never fully lift. Yet alongside the grief, there’s also tenderness and love of life, the same themes I’ve found so comforting in each of Oz’s novels.

Even in its early chapters, the book feels like a reckoning between what we dream of and what’s lost or never came to be, between the Israel that was imagined, and the one that exists. As someone who came here with her own mixture of hope and uncertainty, I find comfort in Oz’s refusal to idealize the past, present, or future. What I read in his novels is that we are all humans, still trying to make sense of the world we feel was promised, and the world we see.

Why I Keep Reading

When I look back at the past two years, and while writing this article, I’ve realized that Oz’s novels each caught me mid-transition, and at each stage they helped me to think in new ways. They’ve been companions, teachers, and mirrors.

People tell me Oz is too dark, too critical, and too sad. But I don’t see him that way. To me, he’s radically honest, and sharply perceptive of human nature. His books have taught me to be more patient, and to be okay with living with a bit of contradiction—in myself, in others, in Israel, and in ideas.

Oz wrote about the questions that still fill the silence for me after candle-lighting on Friday night: how to live, fully and truthfully, with all the light and all the darkness intertwined, and be satisfied.

Maybe, if you find yourself wondering about those same questions, you’ll pick up Amos Oz too.