Your 18Forty Guide to the Parsha is a weekly newsletter exploring five major takeaways from the weekly parsha. Receive this newsletter every week in your inbox by subscribing here. Questions or feedback? Email Rivka Bennun Kay at Shabbosreads@18forty.org.

This project is made possible with support from the Simchat Torah Challenge and UJA-Federation of New York. Learn more about the Simchat Torah Challenge and get involved at their website.

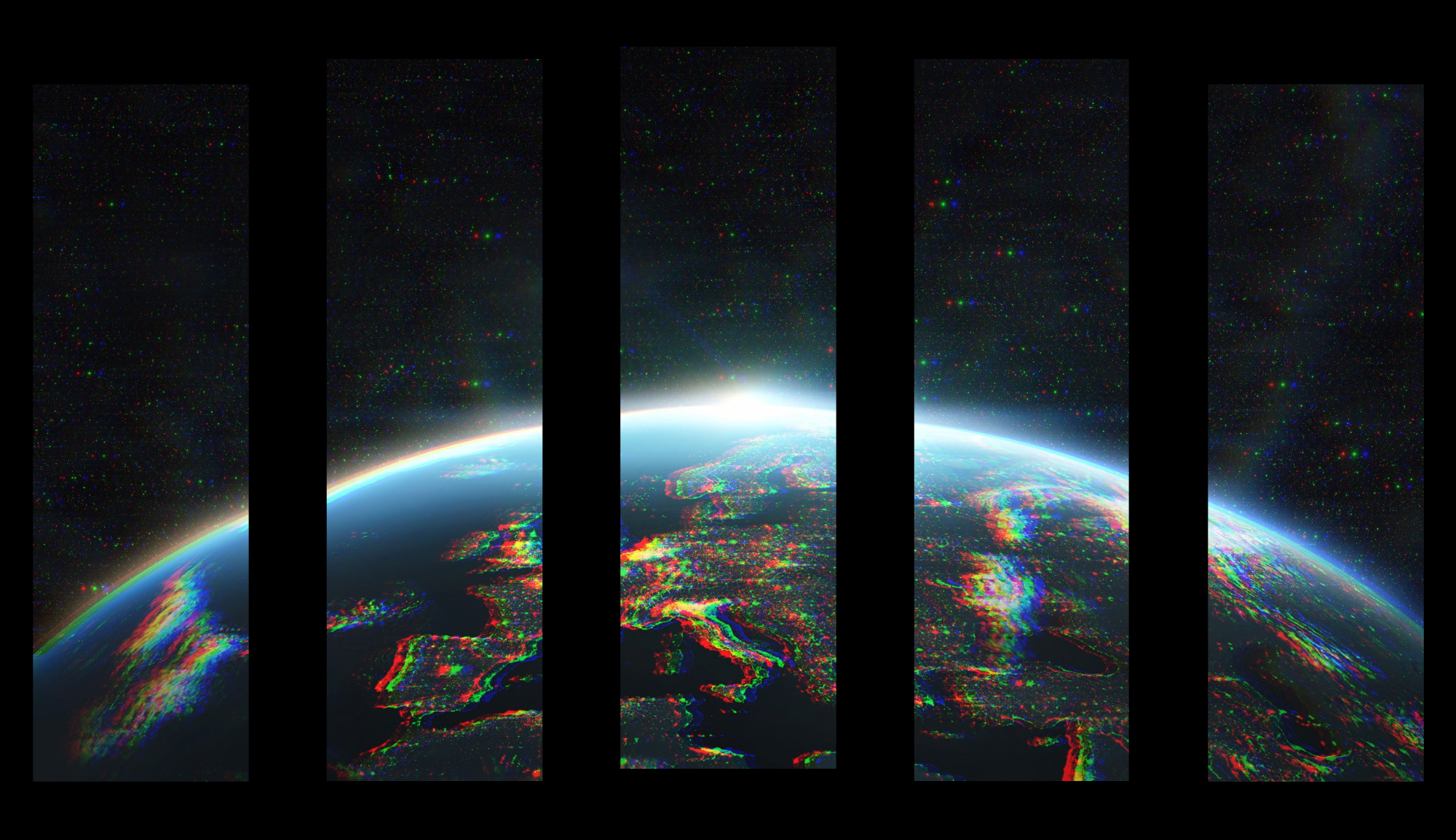

The universe emerges from nothing, light separates from darkness, waters divide, and life springs forth. In the first chapter of the Torah, we read creation’s grand narrative—a story modern readers approach with both wonder and unease. How can these ancient words speak truthfully when science tells us the universe is 13.8 billion years old, not six days old?

The year 5786 brings this question into sharper focus as artificial intelligence accelerates scientific discovery while simultaneously raising profound questions about consciousness, creativity, and what makes us uniquely human. If machines can compose poetry and solve complex problems, what remains sacred about the divine breath that animated Adam from dust?

The problem lies not in the Torah’s account or in scientific discovery, but in the questions we are asking. Previous 18Forty Podcast guest Rabbi Dr. Jeremy England, a physicist and rabbi, explains that the question of God’s existence shouldn’t be framed as a scientific one because it is not a scientific proposition.

The most productive approach, then, is to ask what each of these powerful accounts—science and Torah—can teach us. We can begin by asking ourselves: What is God’s role if the universe is the product of natural law?

“Science takes things apart to see how they work. Religion puts things together to see what they mean,” writes Rabbi Jonathan Sacks. In that spirit, the Torah’s account of creation is less about a scientific chronology and more about profound theological truths.

1. Creation Out of Nothingness: Yesh Me’Ayin

While science describes how the universe developed from the Big Bang, both religion and philosophy grapple with a deeper question: Why did anything come into being at all? Atheist physicist Lawrence Krauss, in his book A Universe from Nothing, argues that physics shows how the universe could have emerged from “nothing.” However, Columbia University philosopher David Albert, in a devastating New York Times review, points out that Krauss’s “nothing” is actually “a highly specific quantum state governed by a set of physical laws.” Albert argues that even Krauss’s sophisticated physics still leaves the core metaphysical question unanswered: Why do the laws of physics exist at all?

The Torah’s assertion of yesh me’ayin, or something from nothing, is a theological statement, not a scientific one, that asserts a foundational truth: The universe is a creation, not an accident. Rabbi Fohrman explains that the Torah’s first word, Bereishit, may not even mean “in the beginning,” but rather “in the mind of God,” suggesting a divine purpose to creation.

Understanding creation through this lens transforms our relationship with scientific discovery. When we learn about cosmic inflation or quantum mechanics, we’re not discovering evidence against God—we’re uncovering the elegant mechanisms through which divine creativity operates. The universe’s mathematical beauty and fine-tuned constants become testimonies to, rather than challenges against, intentional design.

2. Evolution as Divine Method, Not Divine Replacement

The Torah’s account of creation is not a refutation of evolution; rather, it provides the theological and moral framework in which the process of evolution can be understood. The Torah states that God commanded the earth to “bring forth vegetation” (Bereishit 1:12). This simple phrase, used for plants, sea creatures, and land animals, suggests a natural process of development, an inherent capacity for creation built into the universe from the start.

This is a crucial distinction: The Torah doesn’t say God created each species with a wave of His hand, but rather that He endowed the world with the potential to create life. Rabbi Dr. Meir Triebitz explores how this perspective allows for both scientific accuracy and religious meaning.

This perspective helps reconcile the scientific account of human evolution with the theological idea of being created in the divine image, or tzelem Elokim. Jewish tradition understands the divine image not as a physical form, but as a spiritual, intellectual, and moral faculty of the soul. As the Rambam explains in his Guide for the Perplexed, the divine image refers to the intellectual capacity of the human being. Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, in The Handbook of Jewish Thought, reconciles evolution by explaining that evolution provides the “hardware” of the human body, while the soul is the “software” endowed by a divine act. This model allows for both evolutionary biology and the unique spiritual status of humanity.

3. Wrestling with Contradictions is the Core of Faith

The tension between science and faith is not a flaw in the system; it is a feature of Jewish intellectual life. The Talmud interprets the verse from Jeremiah 23:29—”Is not My word like fire … like a hammer that shatters rock!”—to mean that just as a hammer produces many sparks when it strikes, so a single verse of Torah has many meanings.

This teaching forms the intellectual basis for the concept of “seventy faces to the Torah” (shivim panim la-Torah), the idea that Torah can be understood from multiple valid perspectives simultaneously. This teaches us that the Torah is not a simple, one-dimensional book of facts, but a complex, multi-layered text that welcomes multiple interpretations. The Torah, as Rabbi Dr. Triebitz explains, can be understood as one long argument.

Zohar Atkins explores how living with intellectual tension is not a weakness but a strength. When we encounter a scientific discovery that challenges our understanding of Torah, our first response shouldn’t be to dismiss either science or religion, but to ask what new understanding might emerge from their dialogue.

4. The Torah’s Truth is Not Scientific Truth

We often fall into a trap of trying to read the Torah as a scientific document. As argued in The Jewish Philosophy Reader, this is a category error that diminishes both science and Torah. Judaism has always balanced revealed truth with human reason..

The Torah’s authority comes not from its scientific accuracy but from its moral and spiritual insights. While secular literature helps us understand human nature, the Torah’s truth is about meaning, purpose, and our relationship with God—truths that emerge from divine revelation, not human creativity. Previous 18Forty Podcast guest Zohar Atkins articulates that the real goal is to build a spiritual home. We can do this without requiring the Torah to be a physics textbook.

Rabbi Fohrman emphasizes that the Torah functions as a moreh derech—a guide for the path of life. When we approach it as such, we stop asking “Did this really happen exactly as described?” and start asking “What is this trying to teach me about how to live?”

The Torah and science are not competing explanations of reality; they are complementary perspectives. One tells us how the world works, the other tells us what it means. One measures and quantifies, the other provides purpose and direction.

5. Our Role as Partners in Creation

The Torah presents creation as an ongoing process in which humans play an essential role. Adam is placed in the Garden of Eden to “work it and guard it” (Bereishit 2:15). This suggests that humans are not passive subjects but active partners in creation. Our task is to continue God’s work of bringing order and meaning to the world.

As Rabbi Dr. Triebitz notes, science is our attempt to understand the world, and the world is the way that God expresses Himself. This makes our intellectual pursuit a spiritual endeavor. When we study physics or biology, we’re not just satisfying curiosity—we’re participating in the divine act of understanding creation.

This partnership extends to our moral obligations. Understanding climate science compels us to act as better guardians of the earth. Studying neuroscience and psychology helps us understand human behavior and treat each other with greater compassion. Our quest for scientific understanding becomes an act of partnership with the Divine.

Questions for Reflection

- In what ways does learning about science change—or deepen—your sense of the divine?

- Can the universe’s natural laws inspire awe in the same way the Torah does?

- What does it mean to be a partner in creation in today’s world?