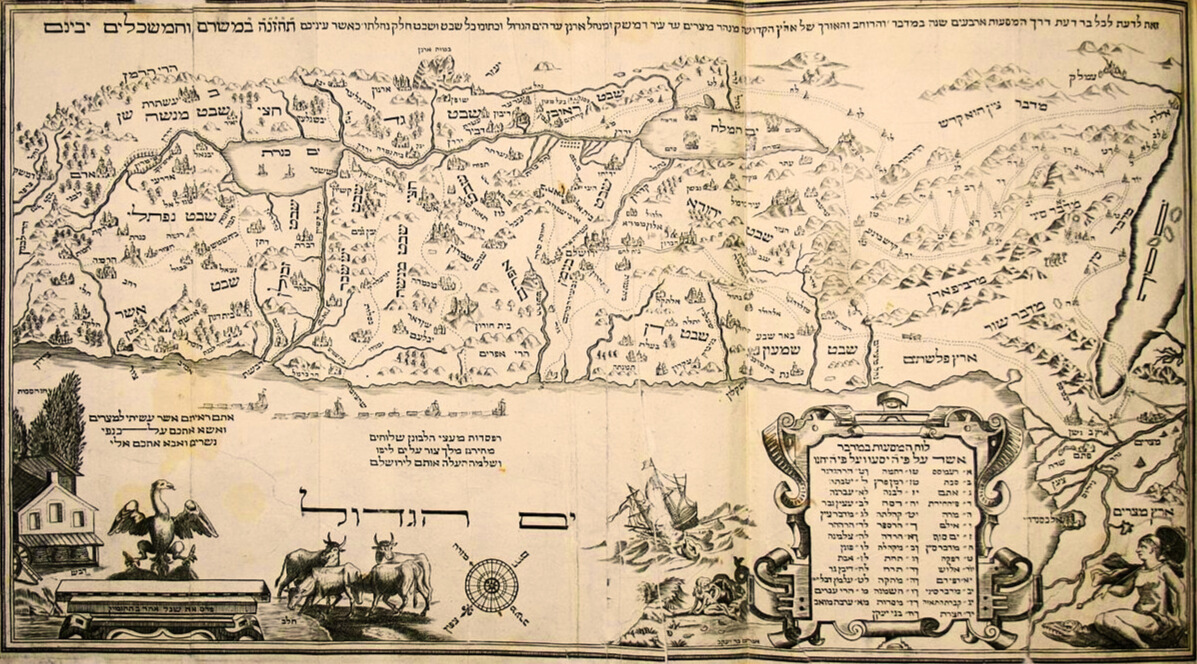

Parashat Masei contains the most detailed description of the borders of Eretz Yisrael provided in the Torah, as given directly by Hashem to Moshe Rabbenu as the people encamp at Arvot Moav, preparing to cross the Yarden into the Land. It encompasses topographical and geological features of the Land, as well as cities; I cite it here in full, as we’ll be examining some of its particulars in detail:

וַיְדַבֵּ֥ר ה’ אֶל־מֹשֶׁ֥ה לֵּאמֹֽר׃ צַ֞ו אֶת־בְּנֵ֤י יִשְׂרָאֵל֙ וְאָמַרְתָּ֣ אֲלֵהֶ֔ם כִּֽי־אַתֶּ֥ם בָּאִ֖ים אֶל־הָאָ֣רֶץ כְּנָ֑עַן זֹ֣את הָאָ֗רֶץ אֲשֶׁ֨ר תִּפֹּ֤ל לָכֶם֙ בְּֽנַחֲלָ֔ה אֶ֥רֶץ כְּנַ֖עַן לִגְבֻלֹתֶֽיהָ׃ וְהָיָ֨ה לָכֶ֧ם פְּאַת־נֶ֛גֶב מִמִּדְבַּר־צִ֖ן עַל־יְדֵ֣י אֱד֑וֹם וְהָיָ֤ה לָכֶם֙ גְּב֣וּל נֶ֔גֶב מִקְצֵ֥ה יָם־הַמֶּ֖לַח קֵֽדְמָה׃ וְנָסַ֣ב לָכֶם֩ הַגְּב֨וּל מִנֶּ֜גֶב לְמַעֲלֵ֤ה עַקְרַבִּים֙ וְעָ֣בַר צִ֔נָה (והיה) [וְהָיוּ֙] תּֽוֹצְאֹתָ֔יו מִנֶּ֖גֶב לְקָדֵ֣שׁ בַּרְנֵ֑עַ וְיָצָ֥א חֲצַר־אַדָּ֖ר וְעָבַ֥ר עַצְמֹֽנָה׃ וְנָסַ֧ב הַגְּב֛וּל מֵעַצְמ֖וֹן נַ֣חְלָה מִצְרָ֑יִם וְהָי֥וּ תוֹצְאֹתָ֖יו הַיָּֽמָּה׃ וּגְב֣וּל יָ֔ם וְהָיָ֥ה לָכֶ֛ם הַיָּ֥ם הַגָּד֖וֹל וּגְב֑וּל זֶֽה־יִהְיֶ֥ה לָכֶ֖ם גְּב֥וּל יָֽם׃ וְזֶֽה־יִהְיֶ֥ה לָכֶ֖ם גְּב֣וּל צָפ֑וֹן מִן־הַיָּם֙ הַגָּדֹ֔ל תְּתָא֥וּ לָכֶ֖ם הֹ֥ר הָהָֽר׃ מֵהֹ֣ר הָהָ֔ר תְּתָא֖וּ לְבֹ֣א חֲמָ֑ת וְהָי֛וּ תּוֹצְאֹ֥ת הַגְּבֻ֖ל צְדָֽדָה׃ וְיָצָ֤א הַגְּבֻל֙ זִפְרֹ֔נָה וְהָי֥וּ תוֹצְאֹתָ֖יו חֲצַ֣ר עֵינָ֑ן זֶֽה־יִהְיֶ֥ה לָכֶ֖ם גְּב֥וּל צָפֽוֹן׃ וְהִתְאַוִּיתֶ֥ם לָכֶ֖ם לִגְב֣וּל קֵ֑דְמָה מֵחֲצַ֥ר עֵינָ֖ן שְׁפָֽמָה׃ וְיָרַ֨ד הַגְּבֻ֧ל מִשְּׁפָ֛ם הָרִבְלָ֖ה מִקֶּ֣דֶם לָעָ֑יִן וְיָרַ֣ד הַגְּבֻ֔ל וּמָחָ֛ה עַל־כֶּ֥תֶף יָם־כִּנֶּ֖רֶת קֵֽדְמָה׃ וְיָרַ֤ד הַגְּבוּל֙ הַיַּרְדֵּ֔נָה וְהָי֥וּ תוֹצְאֹתָ֖יו יָ֣ם הַמֶּ֑לַח זֹאת֩ תִּהְיֶ֨ה לָכֶ֥ם הָאָ֛רֶץ לִגְבֻלֹתֶ֖יהָ סָבִֽיב׃ (במדבר לד א-יב)

And the Lord spoke to Moshe, saying, Command Bnei Yisrael, and say to them, When you come into the land of Kenaan; (this is the land that shall fall to you for an inheritance, the land of Kenaan with its borders:) then the Negev quarter shall be from the wilderness of Tzin along by the border of Edom, and your south border shall be the outmost coast of the Salt Sea eastward: and your border shall turn from the Negev to Maale-Akrabim, and pass on to Tzin: and its limits shall be from the south to Kadesh-Barnea, and shall go on to Chatzar-Adar, and pass on to Atzmon: and the border shall turn about, from Atzmon to the Nachal Mitzrayim, and its limits shall be at the Sea. And as for the western border, you shall have the Great Sea for a border: this shall be your west border. And this shall be your north border: from the Great Sea you shall mark out your frontier at Hor ha-Har: from Hor ha-Har you shall mark out your border to the entrance of Chamat; and the limits of the border shall be to Tzedad: and the border shall go on to Zifron, and its limits shall be at Chatzar-Enan: this shall be your north border. And you shall point out your east border from Chatzar-Enan to Shefam: and the border shall go down from Shefam to Rivla, on the east side of Ayin; and the border descend, and shall reach the eastward projection of the Sea of Kinneret: and the border shall go down to the Yarden, and its limits shall be at the Salt Sea: this shall be your land with its borders round about (Bamidbar 34:1-12).

These would seem to be the authoritative boundaries that dictate the area of the Land’s kedusha (sanctity), including for halachic purposes. There are a number of problems, however, with this apparent peshat: for one thing, the identity of the places mentioned in the Torah are not all certain. For another, there are competing boundaries for Eretz Yisrael both in the Written Torah and the Oral Torah.

Consider, for example, the promise made to Avraham Avinu in Brit Bein ha-Betarim:

בַּיּ֣וֹם הַה֗וּא כָּרַ֧ת ה’ אֶת־אַבְרָ֖ם בְּרִ֣ית לֵאמֹ֑ר לְזַרְעֲךָ֗ נָתַ֙תִּי֙ אֶת־הָאָ֣רֶץ הַזֹּ֔את מִנְּהַ֣ר מִצְרַ֔יִם עַד־הַנָּהָ֥ר הַגָּדֹ֖ל נְהַר־פְּרָֽת׃

In the same day the Lord made a covenant with Avram, saying, To your seed have I given this land, from the river of Mitzrayim [the Nile] to the great river, the river Perat [the Euphrates] (Bereshit 15:8).

While the western boundary presumably remains the Great Sea, i.e., the Mediterranean, and the eastern boundary remains the Yarden (Jordan River), the northern boundary apparently can extend as far north as the Euphrates, while the southern boundary can extend all the way to the Nile. This maximalist expression of Israel’s extent leaves us with the question: what happened between Parashat Lech Lecha and Parashat Masei to shrink the northern and southern extent of Eretz Yisrael? (The text in Bereshit, importantly, goes on to enumerate ten Canaanite nations that Avraham’s descendants would dispossess—although, in the time of Yehoshua, only seven of them are mentioned.)

Moreover, in Sefer Devarim, in Moshe’s speech which takes place just after the communication about the boundaries in Sefer Bamidbar, this maximalist position is again emphasized:

פְּנ֣וּ ׀ וּסְע֣וּ לָכֶ֗ם וּבֹ֨אוּ הַ֥ר הָֽאֱמֹרִי֮ וְאֶל־כׇּל־שְׁכֵנָיו֒ בָּעֲרָבָ֥ה בָהָ֛ר וּבַשְּׁפֵלָ֥ה וּבַנֶּ֖גֶב וּבְח֣וֹף הַיָּ֑ם אֶ֤רֶץ הַֽכְּנַעֲנִי֙ וְהַלְּבָנ֔וֹן עַד־הַנָּהָ֥ר הַגָּדֹ֖ל נְהַר־פְּרָֽת׃

…turn, and take your journey, and go to the mountain of the Emori, and to all the places near it, in the plain, in the hills, and in the lowland, and in the Negev, and by the sea side, to the land of the Kenaani, and the Levanon, as far as the great river, the river Perat [Euphrates] (Devarim 1:7).

כׇּל־הַמָּק֗וֹם אֲשֶׁ֨ר תִּדְרֹ֧ךְ כַּֽף־רַגְלְכֶ֛ם בּ֖וֹ לָכֶ֣ם יִהְיֶ֑ה מִן־הַמִּדְבָּ֨ר וְהַלְּבָנ֜וֹן מִן־הַנָּהָ֣ר נְהַר־פְּרָ֗ת וְעַד֙ הַיָּ֣ם הָאַֽחֲר֔וֹן יִהְיֶ֖ה גְּבֻלְכֶֽם׃

Every place whereon the sole of your foot shall tread shall be yours: from the wilderness to the Levanon, from the river, the river Perat [Euphrates], to the uttermost sea shall be your border (Devarim 11:24)

To make matters more complicated, Chazal give, in Mishna Gittin 1:2 (Gittin 2a), quite narrow boundaries for the purposes of halacha, much smaller than those given in Parashat Masei:

רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר, מֵרֶקֶם לַמִּזְרָח, וְרֶקֶם כַּמִּזְרָח. מֵאַשְׁקְלוֹן לַדָּרוֹם, וְאַשְׁקְלוֹן כַּדָּרוֹם. מֵעַכּוֹ לַצָּפוֹן, וְעַכּוֹ כַּצָּפוֹן. רַבִּי מֵאִיר אוֹמֵר, עַכּוֹ כְּאֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל לַגִּטִּין:

Rabbi Yehuda says: With regard to the borders of Eretz Yisrael, from Rekem eastward is considered to be part of the overseas country, and Rekem itself is like east of Eretz Yisrael, i.e., it is outside of Eretz Yisrael. From Ashkelon southward is outside of Eretz Yisrael, and Ashkelon itself is like south of Eretz Yisrael. Likewise, from Akko northward is outside of Eretz Yisrael, and Akko itself is like north of Eretz Yisrael. Rabbi Meir says: Akko is like Eretz Yisrael with regard to the halakhot of bills of divorce.

In an extensive comment, Tosafot (on Gittin 2a, ד”ה ואשקלון כדרום) explain that there is a distinction between the borders of Olei Mitzrayim and Olei Bavel. Olei Mitzrayim are the generation of the Exodus that came out of Egypt—the people whom Moshe is addressing in Masei, and whom Yehoshua would lead across the Yarden. Olei Bavel, on the other hand, are the Jews who returned from Galut Bavel under Ezra, when permitted by Cyrus of Persia after the destruction of Bayit Rishon. Olei Bavel managed to take back but a small part of Eretz Yisrael, which, for limited halachic purposes, such as the giving of a get—hence its placement in Gittin—is narrowly considered to be “Eretz Yisrael.” This distinction, while highly significant, leaves us with the same question of whether the maximalist boundaries of Brit Bein ha-Betarim or the smaller ones of Masei are to shape our understanding of what Hashem has given us. Where, moreover, does this leave us today, when Jews again possess a larger part of the Land? And more abstractly, what are we to do with seemingly contradictory factual descriptions of the Land within the Torah?

The exacting work of one Ishtori ha-Parchi, a medieval Jew from the south of France exiled from his birthplace along with French Jewry in 1306 (and in smaller waves thereafter), may hold some of the answers. Ishtori did a number of remarkable things when met with misfortune, the first of which was to decide to make aliyah to Israel. Throughout the period of the Rishonim, Jews from across the diaspora made their way home to Israel when permitted. Some went on pilgrimage or out of conviction, others were impelled by dark forces gathering on their doorstep, and still others, like Ishtori, were forced to emigrate by orders of expulsion. While many French Jews scrambled across the borders of royal France, either westward through the Roussillon into Catalunya (northeast Spain) or eastward to the territories held by the Avignon popes in the Comtat Venaissin, which remained open to Jewish settlement, Ishtori figured that he might as well make the ultimate trip home. He arrived in Eretz Yisrael around 1313, after traveling via Cairo.

A physician by trade, Ishtori settled, after a stint in Jerusalem, in Beit Shean in the lower eastern Galil. There he continued to make a living as a doctor, but embarked on a second extraordinary venture: the writing of a comprehensive book on the halachot of Eretz Yisrael, including agricultural tithes, sanctity of the Land, its boundaries, and more. Between the days of Chazal—those who were still able to live in the Land—and 1322, when Ishtori ha-Parchi’s Kaftor va-Ferach tumbled out into the world, no Jew had explored the Land and recorded their research in book form. Ishtori’s work became the first, and for centuries the only, such Jewish work that recorded the historical geography of the Land of Israel. While often styled as a geography, it is important to emphasize that Ishtori’s primary aim in the book is to determine the halacha appropriate to Eretz Yisrael so that it can be practiced by Jews residing there. His keen interest in geography is in service to the larger goal of enhancing the kedusha of the Land and of living in it.

Anyone reading Kaftor va-Ferach cannot help but be awed by its author’s learning, and his special ability to recall and bring to bear every scrap of detail about the topography of the land in rabbinic literature. His method of deciding historical points is certainly not the only one among Rishonim, including those, like Rambam or the Radbaz, who had personal experience of the geography of Eretz Yisrael. It possesses two distinct advantages: it was the fruit of many years of walking the Land, encountering it and researching it in person; and also, Ishtori made an important recognition, bolstered by modern evidence, that Arabic place-names often preserved ancient Hebrew names. The correctness of his approach, or its drawbacks, are not nearly as important, however, as his mission itself: to know the Land and to bring this knowledge to bear on how we understand its holiness, and how we live that holiness.

To demonstrate how Ishtori does so, I want to look at just one example of a significant geographical judgement he makes: the location of Nachal Mitzrayim. According to Ishtori, Nachal Mitzrayim (the wadi of Egypt) is not to be confused with Nahar Mitzrayim (the River of Egypt), which refers to the Nile. (He cites Rashi and Rav Saadia Gaon in support of this contention, though the citation of each has its problems.) He further identifies it with “what the people today call Wadi al-Arish,” three or less days’ walk from Gaza, today a short distance into the Sinai past the modern Israeli border with Egypt. Ishtori concludes:

אם כן ממה שהתבאר קצה ארץ ישראל דרומי מזרחי הוא ימה של סדום, והולך הגבול מתעקם ומתרחב עד הגיעו לנחל מצרים. ממקצוע מערבי דרומי שהוא זה שהזכרנו נטה ונסמן ונתאוה ללכת אל הצפון ביושר דרך שפת הים עד הגיענו אל הקצה הצפוני מערבי והוא הר ההר, שכן כתוב (במדבר לד, ז), וזה יהיה לכם גבול צפון מן הים הגדול תרא לכם הר ההר…ויהיה הים הגדול מצד המערב. עתה הם בידינו שלש קצוות.

If so, from what has been clarified, the southeastern border of the Land of Israel is the Dead Sea (“the Sea of Sodom”), and the boundary continues, bending and broadening until it reaches Nachal Mitzrayim [Wadi al-Arish]. From the southwestern which is that which we mentioned, it turns and is indicated and seeks to go straight northward along the coast of the sea until it reaches the northwestern edge which is at Hor ha-Har (Mount Hor), as is written [in Bamidbar 34:7], “This will be for you the northern border: from the Great Sea you shall see Hor ha-Har”…and the Great Sea will be on the western side. And so we have in our hands three borders (Kaftor va-Ferach 11).

Ishtori proceeds to examine the fourth (northeastern) border, confidently seeking to identify the biblical borders of the Land of Israel. His interpretation is neither the restricted definition of the Mishna nor the maximalist vision of the possibility of Israel’s borders stretching from the Nile to the Euphrates. It hews, instead, close to the boundaries of our parsha, including much of the Negev as far east as the eastern Sinai, where Wadi al-Arish is located. Ishtori does not delve into the spiritual resonances lurking behind the discrepancies in the borders of the Land of Israel; our dilemma still stands in its deeper implications. But what he does do is remind us that these questions are not abstract but can, and must, be worked out.

Ishtori’s exacting research, and its reception by eager readers hungry to know about the Land, demonstrates how precious each geographical datum in the Torah is. Like the tagin on which Rabbi Akiva was destined to hang halachot, each place-name and -marker is a site for Jewish experience. We are called to identify each of the places in Masei. Likewise, we are charged with examining the differences between the maximalist Promised Land of Brit Bein ha-Betarim and the more minimalist promise of Masei, between the conquests of Olei Mitzrayim and those of Olei Bavel. As Rambam avers, the possibility of expanding kedusha is in our hands (Hilchot Terumot 1:2). Today, sovereign in our own Land, we can stand in the place where Yehoshua bid the sun stand still or to which the tribe of Dan was chased from their initial landholding to the north, knowing that the places retain their ancient significance even as they are enlivened anew by our experience of them. In a spiritual inversion of Eliot’s evocative phrase, we arrive where we started and know it not for the first time, but all over again.