In the last two years, the Jewish People have had to mobilize—not only on the battlefield, but in spirit. This moment has demanded that we turn inward, delving deep into the layers of our individual and collective Jewish identity. And it is precisely this question—of identity, of purpose, of the Jewish mission in the world—that stands at the very heart of Rabbi Sacks’ life’s work.

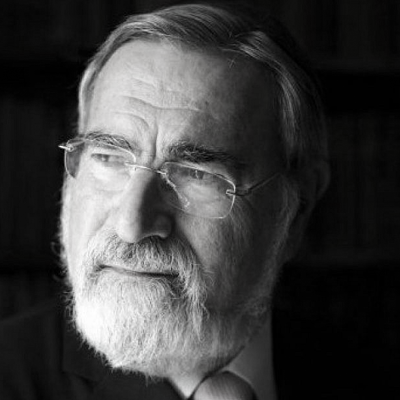

This week marks five years since the passing of Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks zt”l. In those five years, the world has shifted on its axis. We have witnessed fractures and transformations that have left many searching for a language—a moral and spiritual framework—to translate chaos into meaning, to lift experience beyond the immediacy of pain and into understanding.

Since his passing, Rabbi Sacks’ words have reached audiences wider than ever before, resonating with a power that feels almost prophetic—particularly here in Israel. His eloquence, intellectual depth, and moral clarity offer balm to a generation wrestling with rupture and disillusionment. Yet his writings do far more than comfort. They confront the questions that others often fear to face: the tension between democracy and religion, the dialogue between science and faith, the place of Judaism within the wider world, and the complexities of identity in an age of fragmentation and alienation.

Perhaps his greatest gift was his ability to kindle in us a profound Jewish pride—while at the same time reminding us of the moral responsibility that pride demands: to be deeply, courageously human, rooted in the ethical and spiritual vision of biblical Judaism.

Reflecting on his vast and far-reaching oeuvre, one could not hope to capture its scope in a single essay. Yet one idea has continued to echo through my mind over these past two years: his oft-quoted distinction between optimism and hope.

Optimism and hope are not the same. Optimism is the belief that the world is changing for the better; hope is the belief that, together, we can make the world better.

“Judaism,” wrote Rabbi Sacks, “is the voice of hope in the conversation of humankind.”

These short yet powerful lines capture the essence of a uniquely Jewish theology that underpins Rabbi Sacks’ vast and far-reaching thought: a theology that places human freedom and responsibility side by side. That fosters an active virtue of courage to confront the world that is and work towards a world that ought to be. A theology that reinterprets the biblical concept of covenant for the challenges of modern liberal democracies.

It is a theology that places humanity at the center of God’s world, urging us to hear the Divine mandate of tikkun olam—repairing the world—not as a vague call for social justice—often a siren call in the midst of chaos—but rather as a sacred partnership with God. It is a theology that views Judaism not merely as a religion for Jews, nor as a universalist call for all humanity, but as something in between—a particular destiny with universal implications.

And at the heart of it all stands one defining concept: hope—tikvah.

A Theology of Hope and Responsibility

Rabbi Sacks’ book To Heal a Fractured World offers his response to two prevailing outlooks on redemption—ge’ulah—that have shaped both religious and secular visions of how the world might be transformed.

The first is a religious outlook that passively waits for divine intervention—a belief that redemption will arrive in an apocalyptic moment when God steps in to fix everything.

The second is a secular vision, epitomised by thinkers such as Karl Marx, which calls for a revolutionary dismantling of the existing order—believing that through human effort alone, a utopian society can be created.

While Marx famously criticised religion as “the opium of the masses,” his vision, Rabbi Sacks argued, ironically mirrored the very apocalyptic framework he opposed. Both the religious fatalist and the secular revolutionary reject the world as it is, insisting that redemption can only come through destruction and total reconstruction.

Both, therefore, offer false promises—quick fixes to profound and complex human problems: inequality, environmental crisis, religious violence, moral decay.

Rabbi Sacks rejects these revolutionary models. In their place, he offers a distinctly Jewish vision of redemption: one rooted not only in belief in God, but in God’s belief in humanity.

This vision is not about sudden transformation. It is a call to partnership—grounded in the slow work of cultivating character, nurturing empathy, deepening compassion, and living with commitment to both tradition and the world.

For Rabbi Sacks, engagement with the world is not a distraction from holiness; it is the very arena in which holiness is tested and revealed through human effort.

The Abrahamic Revolution

This vision of engagement—the belief that human beings are partners in God’s work—lies at the heart of what Rabbi Sacks calls the Abrahamic revolution.

Abraham’s journey begins, according to the Midrash, when he sees a castle engulfed in flames and cries out, “Where is the owner? Why is he not putting out the fire?” The owner—God—appears and calls out to Abraham, inviting him to join in extinguishing the flames.

For Rabbi Sacks, this story captures the essence of Judaism’s mission: it begins not with an answer, but with a question. God does not simply respond to Abraham’s cry; instead, He invites Abraham—and through him, all of humanity—into partnership in healing a fractured world.

This is the Abrahamic revolution: the belief that the world can be other than it is. That change is possible even in the midst of evil and despair. And that it depends on us.

As Rabbi Sacks so often said: “More than our faith in God, Judaism is about God’s faith in us.”

This radical idea—that God calls upon human beings to be His partners—was revolutionary in the ancient world, dominated as it was by fatalism and submission to capricious gods. It remains equally revolutionary today, challenged not by pagan deities but by the determinisms of modernity—biological, technological, or ideological.

Throughout history, Jews have been the great protestors against fatalism. Not only in creed but also in deed—we have rarely allowed fate to define us. Despite centuries of persecution, displacement, and antisemitism, we have risen above victimhood to reclaim agency.

This is not merely a story of national resilience. It is a story of theological courage—a faith that insists on responsibility and action, even when hope seems absurd.

Engaging the World: The Jewish Mission

And it is for this reason, Rabbi Sacks argued, that Jews must never isolate themselves from the world. Judaism was never meant to be a universal religion, but it was always destined to carry a universal message.

The Jewish People, he insisted, were not meant to be—as the non-Jewish prophet Balaam once said—“am levadad yishkon,” a people who dwells alone. Rabbi Sacks, in his book Future Tense, reads those words not as a blessing, but as a curse.

Being a pariah people is not a virtue. Our mission can only be fulfilled through engagement—not separation. We are called to be a light unto the nations, and that calling demands openness: to open our tents, as Abraham did, to those who are different from us; to stand at the threshold between our particular identity, which we must cherish and protect, and the universal mission of humanity, which we must pursue, surrendering neither one.

And despite the immense challenges of antisemitism and assimilation, we must never give in to resignation, disillusionment, or fear—for to do so would be to collapse under the weight of fatalism. And fatalism feeds passivity. And passivity, Rabbi Sacks warned, will never bring about change.

And then the Jewish mission would have failed.

That is why, time and again, Rabbi Sacks reminds us that Judaism’s vision of hope is not about waiting passively for redemption, nor about revolutionary calls for a utopian reality, but about active engagement in the world. The Bible does not begin with the dramatic overthrow of an empire in Exodus, but with the messy, intimate work of family dynamics. This, in Rabbi Sacks’s words, teaches us “the primacy of the personal over the political.”

While Exodus speaks of grand themes—liberty, redemption, salvation—Genesis delves into the complexities of the human heart. As Rabbi Sacks writes, “If we cannot create peace, compassion, or justice within the family, we will be unable to do so within the nation or the world.” Judaism’s mission, rooted in this biblical vision, strives for universal goals without ever losing sight of the particular and deeply personal dimensions of life. Judaism exists in the tension between the universal and the particular, charting a path through the narrow, sacred space where they converge. It is a religion that seeks change through hope.

Rabbi Sacks: Prince Among Nations, Vision of Big Judaism

Rabbi Sacks’ life was itself a living embodiment of that mission. Like our forefather Abraham, he carried God’s message into the public square, becoming in every sense a prince among the nations—a voice of conscience and moral clarity, speaking truth to power and challenging the idols of our age: radical individualism—the “selfie culture,” as he wryly called it—rampant consumerism, empty religious behaviourism on one side, and militant secularism on the other.

Whether as a lord in the British Parliament addressing prime ministers and princes, or in public debate with thinkers such as Richard Dawkins, he spoke truth without rancor and faith without fear. He never used his influence for personal gain, nor allowed conviction to calcify into self-righteousness or binary thinking.

Like Abraham, he combined protest with humility, courage with compassion. He elevated ignorance with a rare synthesis of ancient and modern wisdom, restoring dignity to faith and rekindling respect for monotheism and religion itself. He understood that to be a voice of faith in the secular world was not to dominate but to illuminate—to remind humanity of the moral and spiritual dimensions so easily drowned out by the noise of power and progress.

Perhaps another reason his writings resonate so powerfully today, especially in Israel, is that they articulate what might be called a big Judaism—one that urges us to see our faith through a telescope rather than a microscope.

Judaism, he taught, is more than nomos—more than dry legalism or ritual formalism. It is a way of life that embodies some of the greatest moral and spiritual ideas ever gifted to humanity. Torah, mitzvot, and halacha form the scaffolding that upholds an edifice built of eternal truths: the sanctity of life, the dignity of the individual, the ethics of responsibility, covenantal society, the equality and freedom of all, the sanctity of difference, and the audacity of hope.

Ideas alone will die if not enacted within the cadence of a living ritual, woven into daily habit, memory, and community. Judaism offers not an abstract philosophy, but a particular way of being in the world—a pattern of living that transforms universal ideals into embodied reality. Its particularity is precisely what allows its truth to radiate outward, to project universal meaning through its distinct form. Perhaps this is what makes Judaism uniquely positioned to serve as a beacon of active hope in an age of disillusionment.

I remember one of my meetings with Rabbi Sacks, when I sought his guidance on a deeply personal dilemma. I asked for an answer. Instead, he said gently: “I know you can and will do what you need to do. But I cannot tell you whether now is the right time. Only you can decide.”

I left the meeting slightly disappointed that he hadn’t given me the clarity I craved. In time, I made my choice. And with hindsight, I realised that in that moment, Rabbi Sacks had taught me more about Jewish theology than any answer ever could. He had taught me the essence of a living faith: That the answer lies within, that God’s faith in us must inspire our faith in ourselves. That we are called to act, to choose, to build—to break every glass ceiling imposed upon us.

And even when we cannot achieve all we dream, we find meaning in knowing that we are part of an eternal people—a people who carry the banner of hope through the generations. A people whose story continues beyond our own, extending the covenant of responsibility and faith long after we are gone.

This is why hope stands at the very fulcrum of Rabbi Sacks’ systematic theology—a theology that, in his timeless words, enables us to rise each morning, even when darkness descends upon the world, and dedicate ourselves anew to being a light that shines outward:

That is what hope is in Judaism: a refusal to give up on your deepest ideals, but a refusal likewise to say, in a world still disfigured by evil, that the Messiah has yet come, and the world is saved. There is work still to be done, the journey is not yet complete, and it depends on us: we who now all too briefly stride upon the stage of time. The Bible is not metaphysical opium but its opposite. Its aim is not to transport the believer to a private heaven. Instead, it is the impassioned, sustained desire to bring heaven down to earth. Until we have done this, there is work still to do.

Five years on, we—his students—miss his voice more than ever. Yet because he believed so deeply in us, in humanity, and in the Jewish People, we continue his legacy. Hearing the call of the Jewish mandate of hope, each of us, in our own way, continues to strive to be that voice of hope in the ongoing conversation of humankind.

Yehi zichro baruch. His memory has indeed become a blessing to us, the Jewish People, and a beacon of hope in a disillusioned world.