I Read This Over Shabbos is a weekly newsletter from Rivka Bennun Kay about Jewish book culture, book recommendations, and modern ideas. Receive this free newsletter every week in your inbox by subscribing here. Questions, comments, or feedback? Email Rivka at Shabbosreads@18forty.org.

The year was 1933. Lubavitch’s Frierdiker Rebbe—who was then simply “the Rebbe”—had just moved to Warsaw, and he tasked three yeshiva boys with unpacking his personal library, which was enormous: “twelve large crates of seforim,” which the students would use to fill up 12 bookcases.

“He told them to handle the books with care, and, above all, not to open them,” historian Dovid Zaklikowski writes.

That last instruction proved difficult to follow, as the crates contained “original manuscripts and priceless first editions.” Nevertheless, they persevered.

That is, until they came across a booklet of letters from the Sfas Emes to the Rebbe Rashab (the fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe).

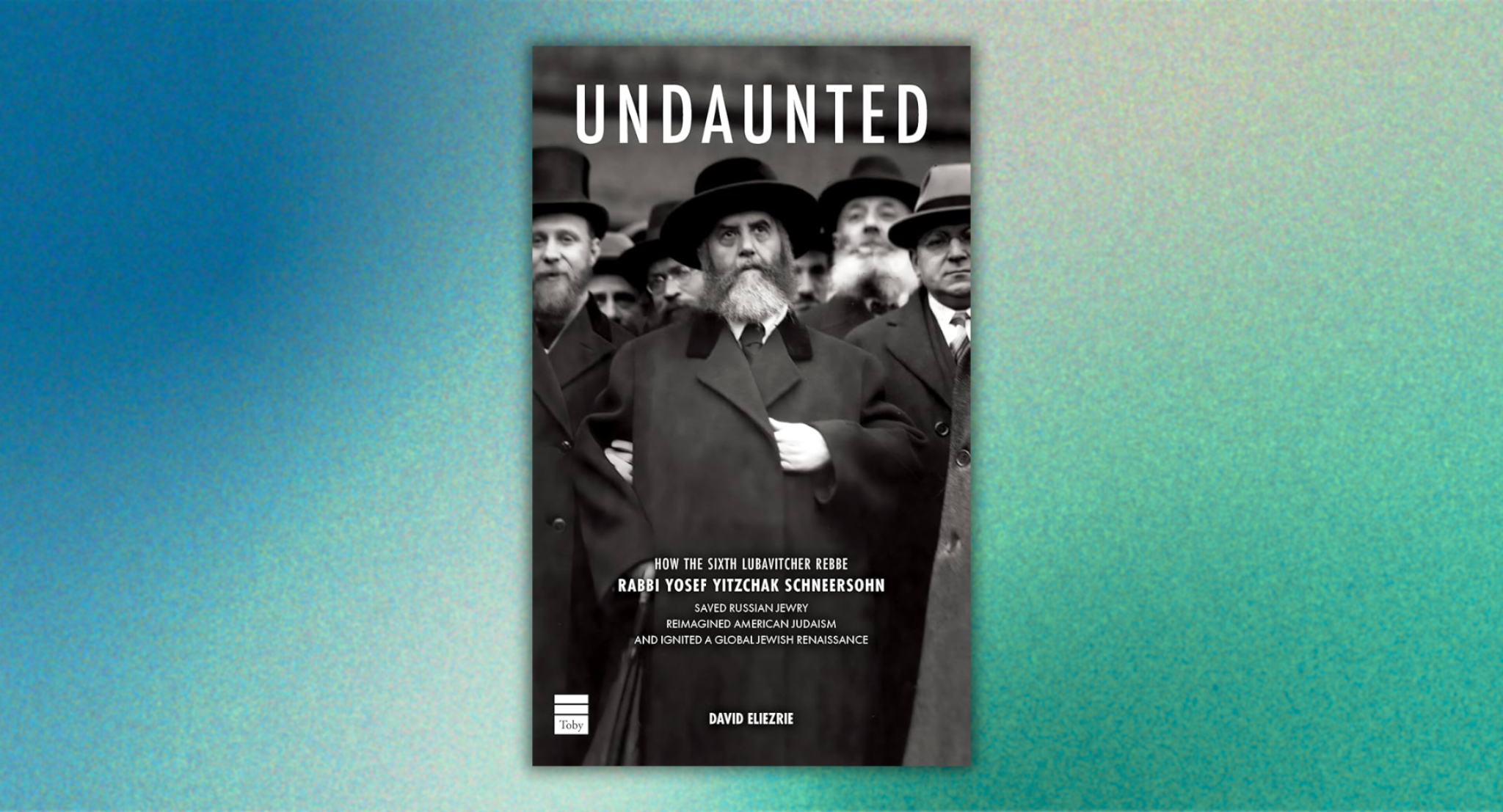

“As they crowded around to peek, the Rebbe himself walked in and caught them in the act,” David Eliezrie writes in Undaunted, his new biography of the Frierdiker Rebbe, subtitled How the Sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, Saved Russian Jewry, Reimagined American Judaism, and Ignited a Global Jewish Renaissance.

“We almost fainted,” said Moshe Gerlitzky, who was 18 years old at the time.

“The students were beside themselves with embarrassment,” Zaklikowski writes, “but the Rebbe merely smiled.”

“Just don’t look into it,” the Rebbe said.

This is one of the many stories told in Undaunted, which—with its danger, heroism, and international intrigue—would be worthy of an action-packed TV miniseries if there were enough Jews to make a market for such a thing.

I, however, was more interested in what the book had to say about the Rebbe’s interface with America, where he arrived after a daring escape from World War II.

The Frierdiker Rebbe is famous for saying “America iz nisht andersh.” (“America is no different.”) But what was the context? What did the Rebbe really mean?

You have to start, I gathered from the book, with a much earlier saying of his: “Make America a place of Torah.”

America, the conventional wisdom said, was where Yiddishkeit went to die.

As Bernstein says in the film Hester Street: “When you get on the boat, you should say, ‘Goodbye, O Lord, I’m going to America.’”

American Jews were largely willing to assimilate—or to embrace a rugged individualism and remake Judaism according to their own preferences. The Conservative and Reform movements were quickly scooping up Jews who came from traditional families but felt America gave them the opportunity to forge a different path via a new Judaism.

The Rebbe, though, upon his arrival in America, echoed his words from a decade before, saying, “I came to make America a center of Torah … America is no different. It will become a center of Torah.”

This was met with immense skepticism, even from those deeply invested in the continuation of Orthodox Judaism.

“The primary strategy of the time was defensive,” Eliezrie writes, “to shore up the small core of observant Jews and stem the Orthodox attrition that would not abate for years.”

Eliezrie goes on to explain:

The Rebbe’s strategy was the opposite; he chose to go on the offensive. His proclamation, “America iz nisht andersh – America is no different,” challenged the prevailing attitude. He didn’t want to just bolster the small religious community, but to fundamentally change the direction of American Jewish life.

For the Frierdiker Rebbe, going on the offensive meant putting a premium on establishing Jewish education, maximizing the quality and availability of Jewish learning in as many places as possible. Eliezrie writes in sum:

The Rebbe’s theme of “America iz nisht andersh – America is no different” challenged the mindset that Judaism must change in order to thrive in the US. He was a pioneering force in Jewish education in America, creating the first national Jewish network of day schools, complemented by supplementary programs, youth clubs, and educational curriculums. He instilled new pride in Jewish tradition, changing the trajectory of American Jewry.

Undaunted made me wonder: What would it mean for us to play offense today? And, if education was the frontier of the Frierdiker Rebbe’s generation, what is the area for growth in our time? Is it combatting antisemitism? Healing political and religious divides? I wouldn’t think so, as those were arguably bigger issues in the Frierdiker Rebbe’s generation than they are now—yet he chose Torah and education.

Now that the Rebbe’s words—“America is no different. It will become a center of Torah”—have proven correct, prophetic even, what kind of offense can we play with such a strength on our side?