Ever since I was a little child, I was fascinated by mysticism. In third grade, I used to lie to my friends that my grandfather, a rabbi (this part was true), was also a Jewish mystic (not at all true). What drew me to mysticism? I think it was a fairly simple, dare I say childish, commitment that there is more to the world than what we can rationally see or explain. That was the way I saw the world then and continue to see this world. With time, mysticism became a more formal system and approach through which I applied that founding principle to God, Judaism, texts, and—most importantly—myself.

Mysticism can seem like a troubling proposition for those committed to purely rational thought. Particularly as analytic philosophy and its more practical cousin, computer programming, become more prized forms of thinking. Mystical thinking has been discarded by many as a relic of a more ignorant human past in favor of computation as representative of a more idealistic future. While I appreciate the advancements that the modern world has achieved, I do think it can at times obscure what is, in fact, real.

In twelfth grade, I had a brilliant art teacher named Darren Singer. He had a striking artistic mind and a very warm spiritual soul. He taught me how to charcoal and introduced me to the musical sounds of Medeski Martin & Wood. His most lasting influence on my life was from a small book he recommended called The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. I later discovered that my distant cousin, Stacy Schiff, wrote a biography on the author that was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. The Little Prince is a profound book. While it is written for adults, the book is actually dedicated to a childhood friend and reads:

I ask the indulgence of the children who may read this book for dedicating it to a grown-up. I have a serious reason: he is the best friend I have in the world. I have another reason: this grown-up understands everything, even books about children. I have a third reason: he lives in France where he is hungry and cold. He needs cheering up. If all these reasons are not enough, I will dedicate the book to the child from whom this grown-up grew. All grown-ups were once children—although few of them remember it.

In many ways the entire book proceeds from the sentiment within this dedication. It is a book about recovering the lost innocence and wonder of childhood. Each chapter shares a different short story of the fantastical travels of the mysterious Little Prince as he tries to understand why the adult masses in the world seem to occupy themselves with such trivial behavior. In one of the most famous and moving passages in the book, the protagonist explains how he has kept his childlike wonder:

Here is my secret. A very simple secret. It is only with the heart that one can see rightly. What is essential is invisible to the eye.

I think this moving line captures much of what mysticism tries to cultivate: learning to see with your heart. Mysticism begins to articulate what otherwise would be ineffable.

Jewish mysticism in particular is less about a confined set of texts than a reorientation of sorts towards understanding…

Shalom Carmy, in a powerful essay entitled Forgive Us, Father-in-Law For We Know Not What to Think: Letter to a Philosophical Dropout, describes the difficulty of seeing that which is otherwise invisible to the eye:

C.S. Lewis says somewhere that if you point at something, a normal human being will want to know what you’re pointing at; a dog will come up and sniff your finger. That is how a dog thinks. Adopting this perspective, you can consistently assert that a painting has no transcendent meaning—that it is no more than an arrangement of colors on a surface, one which people happen to interpret as a picture of another thing, and you can argue that the fact that people ascribe depth and meaning to this visual image is to be explained fully through reference to the arrangement of these persons’ nervous system. You can dismiss spiritual insight the same way: our supposed experience of God is nothing but a physiological reaction to mundane sensory input—keep your eye on the finger, not at what it signifies.

The difference between staring at a finger versus what the finger is pointing towards is an apt metaphor for how Jewish mysticism refocuses our perspective. Jewish mysticism in particular is less about a confined set of texts than a reorientation of sorts towards understanding what Jewish law, Jewish texts, and, most importantly, life itself is pointing towards.

I recently wrote an article for Tradition, as part of their symposium on Jewish thought, entitled, “Jewish Thought: A Process, Not a Text.” In order to introduce my approach to Jewish thought, I introduce readers to the three role models who in turn introduced me to the works of Rav Tzadok HaKohen of Lublin (1823-1900), a Hasidic thinker who played an essential role in my personal development. Each of my teachers – Rav Moshe Weinberger, Dr. Yakov Elman, and Dr. Ari Bergmann – highlighted a different component of how Jewish thought should impact our thinking. Rav Moshe Weinberger, whose introduction to the works of Rav Tzadok I have discussed in other contexts, modeled the importance of experiential resonance: mysticism that both reflects and elevates personal experience. Dr. Yakov Elman introduced me to the importance of omnisignificance: “the basic assumption underlying all of rabbinic exegesis that the slightest details of the biblical text have meaning that is both comprehensible and significant.” And Dr. Ari Bergmann introduced me to the world of consilience, a jumping together of knowledge by the linking of facts and fact-based theory across disciplines to create a common groundwork of explanation. Each of these animate the world of Jewish mysticism ensuring that it is not reduced to a body of texts, but can become a life-guiding perspective. As I write:

Studying Jewish thought—with a focus on this unifying process, rather than on learning a specified body of texts—is an antidote for the drawbacks engendered by the push towards immediate practical application. Jewish thought, then, is not a text—it is an orientation. Experiential resonance, the search for omnisignificance, and a search for consilience can transform a focus on the formal study of texts about Jewish thought into a life filled with moment of meaning, that ultimately become a more thoughtful life, and a more meaningful Judaism.

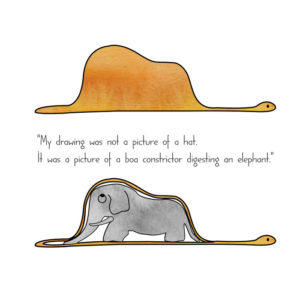

Talmud says that prophecy was taken from the prophets and given to children (Bava Batra 12b). At some point in all of our lives the childlike wonder we each had begins to diminish. The Little Prince was frustrated that adults mistook his drawing of a boa constrictor digesting an elephant for a hat. C.S. Lewis bemoaned those who looked at a finger instead of towards where it was pointing. And Jewish mysticism helps restore our wonder and focus our perspective on what is truly essential. “It is not what is on the page; it is what is within us.”