I Read This Over Shabbos is a weekly newsletter about Jewish book culture, book recommendations, and modern ideas. Receive this free newsletter every week in your inbox by subscribing here. Questions, comments, or feedback? Email Rivka at Shabbosreads@18forty.org.

Growing up Sephardic in a predominantly Ashkenazi community meant that religious practice at home looked different than it did at school.

During the week I davened in Nusach Ashkenaz, the way my teachers taught me, but on Shabbat I davened in Edot Hamizrach. I didn’t mind the differences in practice—if anything, they enriched my prayer and enabled me to enjoy a variety of prayer cultures—but they often left my prayers feeling a bit out of place.

The term nusach refers to the specific wording and structure of prayer, and nuschaot differ based on the customs of different Jewish communities. When it comes to nusach, writes Rabbi Eliezer Melamed, family custom is so significant that one should keep to their tradition even if they know a different nusach is more precise.

The challenge of praying in a foreign nusach only emerged last year—when, for the first time in my life, I spent the Yamim Noraim in Ashkenazi shuls.

At each juncture of the tefilla, I felt unsure what to do. Whenever I felt confident I knew what would happen next, the kahal (congregation) would begin singing to a tune I did not know. During the silent amida of Mussaf on Rosh Hashanah, I waited expectantly for the baal tokeia to blow the Shofar during davening, only to learn that Ashkenazim don’t practice this way. Each time I thought I knew what to expect, I was surprised.

Those familiar with the different nuschaot are aware that in general, Ashkenazi and Sephardi davening could not be more different. Whereas Ashkenazim recite things to themselves and often supplement their tefilla with soulful niggunim, Sephardim chant and recite everything out loud. Davening with Ashkenazim is uplifting; davening with Sephardim, their voices rising in unison, feels like I’m praying with my ancestors.

Davening on the Yamim Noraim in an unfamiliar nusach is difficult. I learned that Ashkenazi Yamim Noraim prayers consist of a certain call and response; the chazan (cantor; the one leading prayers) sings a few words, and the kahal hums a tune in response. If you didn’t grow up with it, you have no idea what is going on.

I’d always considered myself fairly familiar with Ashkenazi prayer and culture—I know the Shabbat tunes and what an Ashkenazi Torah reading sounds like—but when it came to the High Holiday prayers, I suddenly felt like a complete outsider—as if I were peering into another heritage that is not my own.

This difference became even clearer to me when I encountered Ashkenazi piyyutim. (A piyyut is a liturgical poem, often designated to be sung or chanted, usually during the holidays and on special Shabbatot.) The liturgy of the Yamim Noraim is exceptionally different in Ashkenazi and Sephardic communities, underscoring many of the differences between Ashkenazi and Sephardic Yamim Noraim prayers. Ashkenazi piyyutim are often dense, contain difficult vocabulary (think kinot on Tisha B’Av), and use irregular meter. Sephardic piyyutim, by contrast, rely on regular meter, rhyme scheme, and clear Hebrew language.

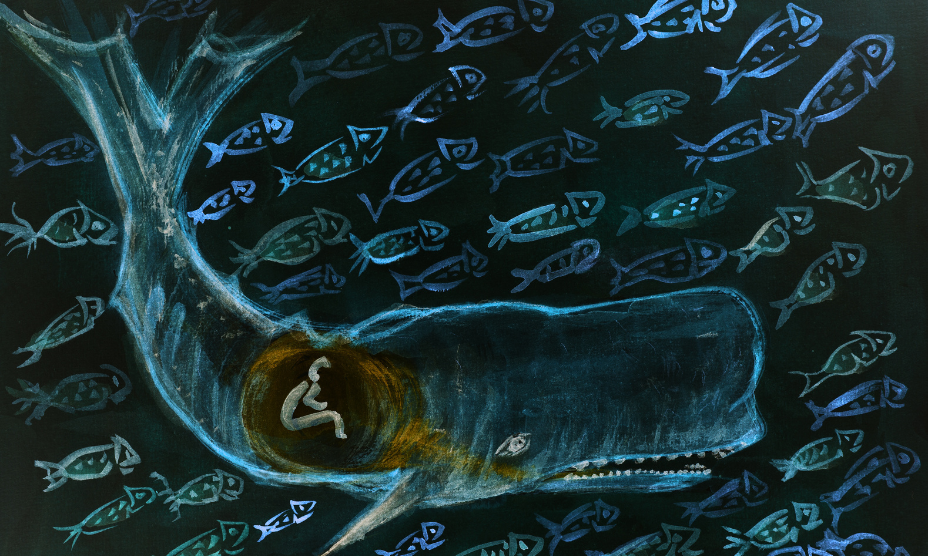

One of my favorite Sephardic piyyutim recited before the blowing of the Shofar, Et Shaarei Ratzon, retells the story of Akedat Yitzchak. At the climax of the piyyut (to me, at least), as he is about to be sacrificed, Yitzchak speaks up:

Tell my mother that her joy has turned away—

The son she gave birth to at ninety years of age

Has gone to the fire, and been designated for the knife.

Where will I find a comforter for her, where?

It pains me for my mother to cry and sob.

In this reading, Yitzchak worries for his mother—Sarah, who waited so many years for a child, will soon find out her only son has been sacrificed—and wonders, “Ana avakesh na menachem, ana?” Where can I find comfort for my mother? Maternal sorrow and an elusive sense of nechama color Yitzchak’s torment. These themes accompanied my Shofar experience throughout the years.

Undoubtedly, the reason this stanza strikes me the most is because of the way we sang it in my shul growing up. We would sing the first half of the piyyut to one tune, and when we would reach the stanza that begins with the words “Sichu le’imi,” “Tell my mother,” the tune would change, signifying a dramatic turn of events. Not only is there significance to praying in your own nusach, but the experience of praying in your hometown shul is irreplaceable.

Associating the High Holiday prayers with home led me to think about how I define home. As transcendent and stirring as the Ashkenazi tefillot are, I find myself yearning for what’s familiar to me; more specifically, I yearn for tefillot that make me feel at home—wherever they may be sung, and however I may encounter them.

Perhaps a marker of growing up is realizing that prayer needs a home—and I don’t mean a physical one. To pray as a grownup means moving beyond the conception of prayer that we were taught as children. Beyond inheriting a culture of prayer—its structure, tunes, and surrounding community—prayer is something that needs to be cultivated and chosen. To pray as an adult is to claim ownership over one’s prayer—to imbue it with meaning, intentionality, personal experience, and life’s daily hurdles.

We conclude the Rosh Hashanah prayers with the words: “Ki beiti beit tefilla yikareh lechol ha’amim”—“For My house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples.” This year, I’m entering Yom Kippur in prayer that my tefillot may find a home.