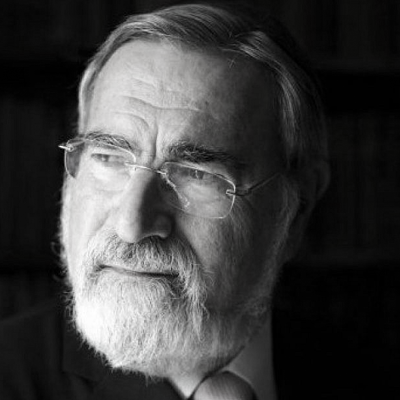

The meeting of science and religion in the modern-contemporary era contributed to a great crisis of faith for many people. However, from this meeting point, many great voices emerged. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks was one such voice, and we lost his this past year. This week, we pay tribute to Rabbi Sacks with a reflection on his stance on science by our staff editor Maury Rosenfeld.

We couple our tribute with a 2015 interview with PBS’ Bob Abernathy and Rabbi Sacks on issues of science and religion. Read his words and appreciate the depth and sensitivity that he brings to all conversations. For interested readers, Rabbi Sacks recently published interview with the On Being podcast, available here, is a must-read (or listen). In that interview, we get a deeper understanding of how his thoughts on the questions of religion in the modern age relate to his respect for all religions. On Being also features some of the most powerful contemporary voices on the complex relationship between science and religion. For those looking for a more legal Jewish angle, check out Rabbi Gil Student’s article on “Halachic Responses to Scientific Developments.” We hope you enjoy, as we embark on this journey on the road towards understanding the relationship between science and religion.

– Yehuda Fogel, Weekend Reader Editor

Guardian of the Crossroads: A Tribute to Rabbi Sacks

By: Maury Rosenfeld

When we come to a major crossroads in history it is only natural to ask who shall guide us as to which path to choose.

This is how the late Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, who passed away earlier this month, opens his book, The Great Partnership: Science, Religion, and the Search for Meaning. Aside from serving as Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth, Rabbi Sacks wrote prolifically and eclectically, including this 370-page treatment of our new topic, Science and Religion.

The accord of living in a world where both subjects coexist – without conflict or contradiction – was so central an issue that it elbowed its way into other writings of his as well; he lectured widely and often on the synchronicity of religion and science, philosophy and morality. As we begin our new topic at a time so close to Rabbi Sacks’ passing, we mention this important and relevant book in order to help frame our own process of discovery that lies ahead.

“Science,” writes Rabbi Sacks, “takes things apart to see how they work. Religion puts things together to see what they mean.” And yet, both are necessary, both are absolutely required in the ongoing rotation of the world and the continuation of reality. The way we need the two hemispheres of the brain to function, he argues, existence needs science and religion.

Before we delve into Judaism’s view of science and religion, let’s take a moment to meditate on what we hope to gain from the journey: deeper meaning. As Rabbi Sacks mentions in the chapter explaining our interest in such a topic: “Science is the search for explanation. Religion is the search for meaning … It is possible to live without meaning. But it will be a strange, foreshortened, defensive kind of life.”

Exploring science and religion isn’t a boxing match of ideas, one side triumphing over the other to be the undisputed heavyweight champion of the beliefs with which we live our lives. It’s a search for understanding, a quest for harmony – and above all – a hungry hunt for meaning.

As a student observed, Rabbi Sacks’ life seems to be less appropriately noted with the traditional “may his memory be for a blessing,” and instead remembered with “may his memory be for a challenge.” A challenge to engage with broad ideas, encounter relationships that seem wrought with tension, difficulty, or even apparent contradiction. May his memory be for a challenge in guiding us through the place where science and religion are intertwined in our religious reality.

A Conversation with Rabbi Jonathan Sacks

February, 2015

BOB ABERNETHY: Now, more of my interview with the renowned retired Chief Rabbi of Great Britain, Jonathan Sacks, who is teaching and lecturing in the U.S. this year. Last week the rabbi spoke here about religion and violence. Today, we begin with religion and science.

RABBI JONATHAN SACKS: Religion and science are two quite different things and we need them both. Science takes things apart to see how they work. Religion puts things together to see what they mean. And the pursuit of explanation — how do things work — and the pursuit of meaning — why am I doing this, why am I here — those are two really fundamental areas of human intelligence and they’re just different. You couldn’t really have religion without science, or we would be servants of nature instead of what God wants us to be — masters of it, responsible masters of it. But we couldn’t really have science without religion or we would discover that we live in a completely meaningless universe and then, you know, things would be very scientific but we would lose our very humanity.

Speaking to Congregation: God can only forgive us if we forgive one another.

BOB ABERNETHY: Sacks believes that religion not only gives life meaning but that it is essential for civilization. He described a religionless life.

RABBI SACKS: I think we can say what a life without religion in the 21st century would look like. It would say that you and I are no more than a collection of chemicals, a whole lot of selfish genes blindly reproducing themselves into the next generation. There is nothing whatsoever that distinguishes us qualitatively from the animal kingdom or any other life form. All ideals are illusions, all hopes are destined to be destroyed and life has no meaning whatsoever.

ABERNETHY: Sacks finds in Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution not so much opposition to religion but support for it.

RABBI SACKS: Darwin came up with one of the most profoundly religious insights of all, because Darwinian evolution tells us that the Creator made creation creative. We now know, having decoded the genomes of everything, all the way up to humans, that all life has a single source from the most primitive bacterium to us. Evolution is actually a profoundly religious insight.

ABERNETHY: Sacks is a philosopher as well as a Rabbi. He says neither reason nor science can prove God’s existence.

RABBI SACKS: People get very rattled when you tell them, of course, you can’t prove that God exists. So, they say, in that case why believe in Him. And I reply, well, you know, prove to me that having a sense of humor is worthwhile. Prove to me that a life without a sense of music is missing something. Prove to me that it’s better to be an optimist than a pessimist. The most important things in life, that it is better to trust than to be suspicious, that it is better to love than to hate.

ABERNETHY: Sacks’ conversations are often rich with stories.

RABBI SACKS: We had a wonderful Jewish atheist, a brilliant man who was a professor of philosophy here in New York at Columbia University called Sidney Morgenbesser. And towards the end of his life when he was suffering quite a lot, [he] said to a fellow philosopher, “I don’t understand why God is so angry with me just because I don’t believe in Him.

ABERNETHY: Sacks says the greatest obstacle to belief in God is the reality of pain and evil. How could a loving god permit so much suffering?

RABBI SACKS: I don’t explain evil. I feel the problem. I actually say, though this sounds very paradoxical, that faith is in the question, not the answer. If you look at the Hebrew Bible the people who raise this question are not skeptics or atheists, they are the heroes of faith. Abraham in Genesis 18 says, “Shall the judge of all the earth not do justice?” Moses in Exodus Chapter 5 says, “God why have you made your people suffer?”

ABERNETHY: Sacks is very proud of the Jewish emphasis not only on study and tradition but on actions — being partners with God to repair the world.

RABBI SACKS: Judaism tends to be a religion of deeds and making the world better, what we call Tikkun Olam. So we really don’t have a problem with atheists or agnostics so long as they are willing to work along with us to make the world a slightly different place. We don’t ask that everyone who comes inside this synagogue believes in all elements of Jewish faith. We just say come and be part of the community, because it is in community that we find meaning, that we find relationship, that we find friendship and love, and it is in community that we change the world.

ABERNETHY: For Sacks, perhaps the greatest argument for religion may be the courage and hope of the people he helps lead.

RABBI SACKS: The most important distinction to make is between two ideas that sound similar and are in fact completely different. One is called optimism. The other is called hope. Optimism is the belief that things are going to get better. Hope is the belief that if we work hard enough, and together, we can help make things better. But it takes a great deal of courage to have hope. No Jew knowing our history can be an optimist, but no Jew worthy of the name ever gave up hope. The story of the Jewish people is the story of the victory of hope over despair and of the spirit over every kind of physical power. We are the people who never gave up hope and I want to say to you, you needn’t be an optimist, but you must never give up hope, because together we can make a better world.

To learn more about science and religion, visit http://upgrapp.com/18forty/science/