Reading Jewish History in the Parsha is a weekly newsletter from 18Forty, where guest writers contribute their insights on Jewish history and its connection to the weekly parsha. Receive this free newsletter every week in your inbox by subscribing here. Questions, comments, or feedback? Email Rivka Bennun Kay at Shabbosreads@18forty.org.

I begin this essay with a disclaimer: I have never served in the IDF. I sit comfortably in the United States and have no right to lecture anyone. I simply seek to understand one of the most radioactive yet consequential issues in our modern Jewish world. The forthcoming is one such modest attempt.

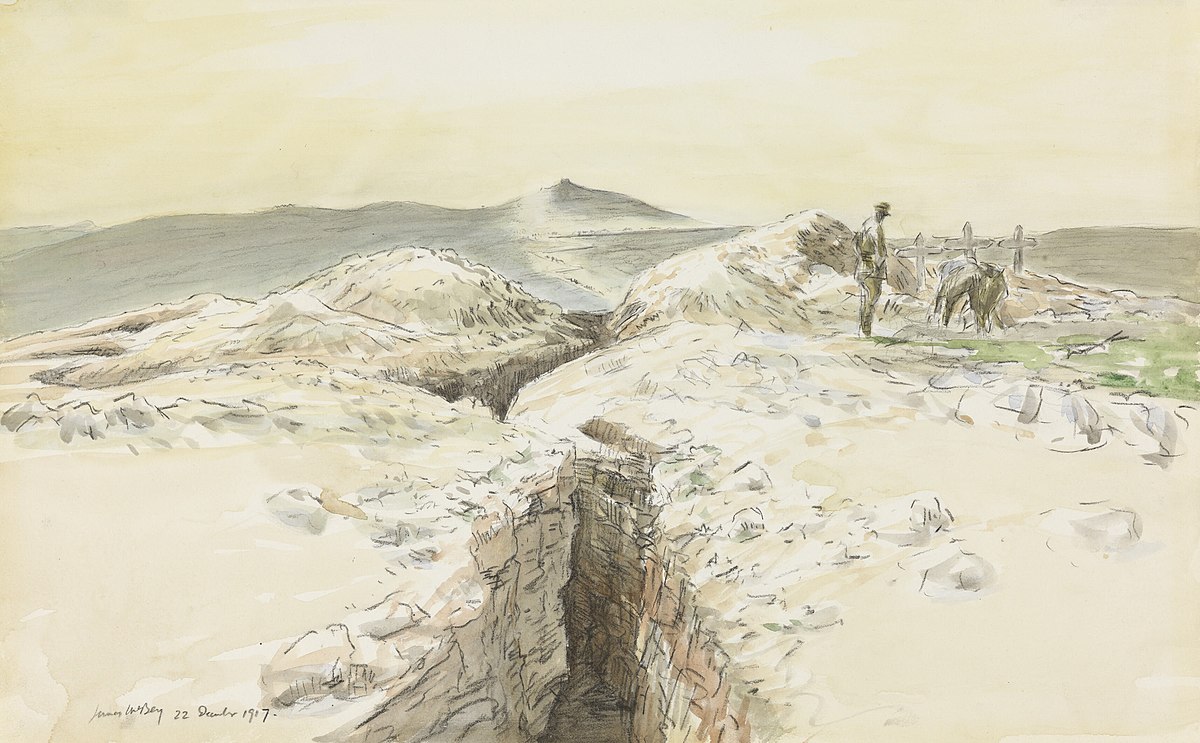

In his memoir, With Might and Strength: An Autobiography (which, incidentally, I read as part of an 18Forty “Book Journey” led by Rabbi Elli Fischer back in summer 2023), Rabbi Shlomo Goren relates an anecdote that today sounds totally unbelievable. Jerusalem was under siege during the War of Independence, and he sought volunteers to dig defensive trenches, on Shabbat, no less.

Following my consultations with Rabbi Herzog, he told me, “We have no alternative. Go and try to meet with the yeshiva students and convince them to volunteer of their own accord. Show them my letter and tell them the situation”…

…Even though the city was under constant artillery fire — including the streets between the neighborhoods of Rehavia, Geula, and Me’a She’arim — and walking the streets was extremely dangerous, there was no other way…I went to a few of the yeshivas. At Hebron Yeshiva, for example, most of the boys were huddled together on the ground floor … I spoke to them in all seriousness, explaining what was about to happen, and they listened in total silence … To my total amazement, when I asked who was willing to volunteer, there was not even one person who did not raise his hand. They were all committed to the task and asked me what they could do and where they should go…

From there, I continued walking to Beit Yisrael and went to one of the Neturei Karta yeshivas. I found all the young men, those who had not enlisted in the Hagana, on the ground floor of the synagogue. There were about two hundred of them. I asked for permission to address them, following Minha, on the subject of saving lives. I told them too, what was about to happen to Jerusalem, G-d forbid, and was so overwhelmed that I choked up and my eyes overflowed with tears … When I finished speaking, not one person refused and there was not a single word of objection.

In the end, more than one thousand volunteers came to help dig the trenches. They dug all night, with all their might. What happened there that night was truly unbelievable. They dug trenches across every single road that could be used by the tanks, and even dug parallel rows of trenches, such that if a tank did not fall into the first trench, it would fall into the second trench. The job was completed as dawn broke, and as the sun began to rise everyone went home to sleep, rest, and daven…

—With Might and Strength, pp. 156-158

Why this sounds so unbelievable today involves a long and complex tale, one which I have been attempting to document in my (shameless plug alert) Iyun podcast, in concert with the Iyun Institute. The roots run deep—theological, political, sociological—and no single essay could untangle them all.

Still, one particular philosophical strand, woven quietly into the fabric of the debate, might help explain part of the gap. And interestingly, it’s a theme that surfaces in this week’s Parsha.

Back in the 1990s, as an active member of NCSY—an organization which our esteemed 18Forty host, Rabbi Bashevkin, has served a national director of education—our leaders often introduced bentching (the Grace After Meals) by declaring that, while many religions prescribe benedictions prior to a meal, Judaism is the only one whose practitioners recite a blessing after eating.

I am no expert in world religions, but a quick AI query does confirm the spirit of this exceptionalist claim. (Apparently, some monastic forms of Christianity, as well as some branches of Islam—”All praise is due to Allah, Who has fed us and given us drink and made us Muslims”—do include post-meal prayers, but these are unusual.)

Interestingly, not only does Judaism include such an after-bracha, but it is likely our only blessing of biblical provenance (perhaps besides those before studying Torah), as the verse in our parsha tells us: “And you shall eat and be satisfied, and bless the Lord your God for the good land that He has given you.” (Devarim 8:10).

Most brachot that observant Jews recite—such as prior to eating or drinking or performing mitzvot—are sourced in rabbinic law, so Birkat Ha’mazon (at least the first sections) actually represents the very paradigm of Jewish blessing itself!

In speculating why the post-meal benediction plays such a primary role, we might invoke the verses immediately after (Devarim 8:11-18):

11 Beware that you do not forget the Lord, your God, by not keeping His commandments, His ordinances, and His statutes, which I command you this day.

12 Lest you eat and be sated, and build good houses and dwell therein…

14 and your heart grows haughty, and you forget the Lord, your God, Who has brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage…

17 and you will say to yourself, “My strength and the might of my hand that has accumulated this wealth for me.”

18 But you must remember the Lord your God, for it is He that gives you strength to make wealth, in order to establish His covenant which He swore to your forefathers, as it is this day.

One who has yet to eat more readily recognizes the need for Divine assistance, but once satiated, often reverts to a detached, agnostic position. This is akin to the man who begs God to find him a parking spot, and upon identifying the perfect location adds, “Never mind God, I figured it out.” Once our needs have been met, we tend to forget how solicitous we were previously, sometimes even arrogantly attributing our satiety to our own moxy.

However, if we read the verses closely, we find not only an exhortation against hubris, but also an acknowledgement of the importance of human effort: “He that gives you strength to make wealth.”

The Torah thus demands that we remember both the Source of our blessing and our own role in bringing it about—a tension that echoes far beyond the dining table.

The question, it seems, is one of proportion; varying streams within Orthodoxy tend to press the scales towards one or another of these poles.

The National Religious community bespeaks breathtaking bravery borne of the belief that human agency is vital in protecting our land and our People. Such an approach reflects the plain meaning of Devarim 8:18, and the thinking of many traditional thinkers throughout Jewish history.

For example, on this verse, Derashot HaRan (10) writes:

It does not state that Hashem, your God, gives you the wealth [ . . . ] but rather that although you create the wealth by your own power, remember that it is God who grants you the power.

On the specific imperative to participate in Israel’s defense, they might point to the commandment, “You shall not stand by [the shedding of] your fellow’s blood” (Vayikra 19:16), or to obligations to participate in a milchemet mitzvah (obligatory/defensive wars). Others would recourse to basic intuition—though the authority of such moral logic itself might be subject to ideological divergence.

Of course, exclusive emphasis on one or another value can generate unintended consequences. One occupational hazard of this position manifests as a provocative and aggressive Messianism that most within the Religious Zionist world disavow, but does persist.

The Haredi world, by contrast, fears that overemphasis on human power can crowd out God entirely. They, too, can summon sources (not only the “Three Oaths” of Ketubot 111a, but many others) that caution patience, humility and deference to Divine orchestration over the puff-chested bombast they observe in the surrounding Israeli culture.

What’s more, among prominent Torah scholars in recent years, a significant intellectual thread has emerged that downplays human effort—not only as limited in importance, but as fundamentally illusory (see, for example, Michtav M’Eliyahu, Michtav 1, pp. 177–206, and Michtav 3, p. 172). One who regards human action as merely “a box to check,” rather than as causatively impactful, will be far less inclined to risk life and limb to pursue it.

Such a position, of course, however principled, carries its own occupational hazards: detachment, indifference, and alienation from large swaths of the Israeli and Jewish public.

Yet history shows that this stance is not immutable. Moments of acute urgency—when the need is clear and the cause uncontested—have seen Haredim step forward with equal vigor. The Jerusalem trench-digging of 1948 was one such example, but far from the only one. Haredim approach medical crises no differently than their peers, and their leadership in organizations like Hatzalah, ZAKA, and Yad Sarah demonstrates that, under the right circumstances, they engage in robust human intervention.

This is why, despite rhetorical cautions against “by the might of my hand,” the limiting factor is rarely the willingness to act in principle. More often, it is how theological ideas become intertwined with broader ideological and cultural forces.

In that context, a belief in the secondary role of human effort becomes far more persuasive as a justification for non-participation. This is especially true when it is paired with mistrust of state institutions, resistance to the Zionist project, or the perception that the army seeks to erode religious distinctiveness through a “melting pot” ethos.

Conversely, as the army and Israeli society at large become more God-centric—publicly invoking Providence, visibly accommodating religious life, and producing leaders who speak the language of faith—those ideological objections lose some of their sting. In such an environment, the “minimal effort” stance no longer needs to serve as a shield against participation, allowing space for Haredim to contribute more actively without feeling they are abandoning core theological commitments.

On this count, at least, we might observe positive developments in the increased invocation of God by prominent figures throughout the war.

Take these remarks from Prime Minister Netanyahu, following the strikes on Iran earlier this summer:

Ten days ago, just hours before launching the historic mission against the evil regime of Iran, I visited the Kotel and again felt a strong urge to wrap myself in a tallit. I prayed for the success of our heroic pilots, our soldiers and commanders, for the security of our nation, and for the peace of our people. I placed a note in the Kotel that read: “Behold, a people rises like a lioness and lifts itself like a lion…”

Today, ten days later, I returned to the Kotel with my wife. Again, I wrapped myself in a tallit and offered a prayer of thanksgiving…

… The most important “siya” (party) in the Knesset is Siyata Dishmaya (Divine providence). We witnessed incredible courage from our fighters and citizens, and immense help from our allies—but above all, we had the help of the Ribbono Shel Olam…

Even if these statements were performative—and who can know the heart of any man?—they were nonetheless profoundly symbolic. And they have been matched by other moments—thousands of soldiers requesting tzitit, and Agam Berger’s dry-erase board message exclaiming, “I chose a path of faith and I returned through a path of faith”—all absorbed by Israelis of every persuasion.

Admittedly, these examples have done little to shift the public rhetoric, which has only grown more strident. Still, one must presume some osmotic transfer into the hearts and minds of Haredi youth who, whatever outsiders might believe, do not live in a hermetically sealed bubble.

Over time, these passionate and talented Haredi young men might observe the evolution from an “army of minim” (heretics) to an “army of ma’aminim” (believers). As they do—like Rabbi Goren’s audiences in 1948—they might raise their hands and step forward as essential players in that transformation.