Your 18Forty Parsha Guide is a weekly newsletter exploring five major takeaways from the weekly parsha. Receive this newsletter every week in your inbox by subscribing here. Questions or feedback? Email Rivka Bennun Kay at Shabbosreads@18forty.org.

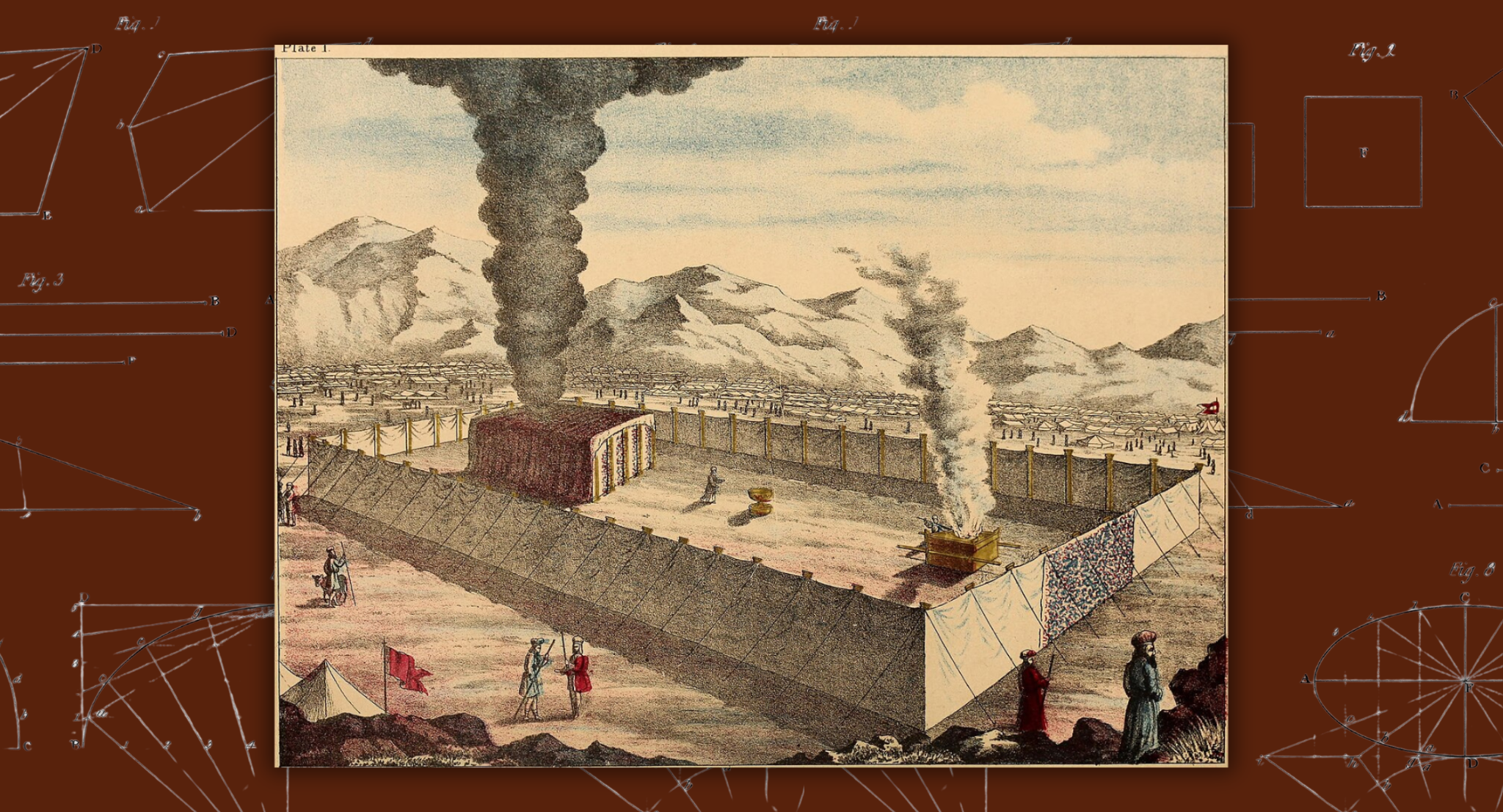

If you’ve ever found yourself tuning out during the Torah readings that fill the second half of Exodus, you’re in good company. After the drama of the plagues, the splitting of the sea, and the thunder at Sinai, the Torah pivots to what can feel like an ancient building code, all cubits and curtains, sockets and clasps, detailed instructions for furniture that no longer exists in a sanctuary that was dismantled millennia ago. Many readers quietly wonder why the Torah devotes such exhaustive detail to these specifications, and what possible relevance any of it could have for life today.

Parshat Terumah arrives right after the revelation at Sinai, where the experience was so overwhelming that the people “saw the voices,” as Exodus 20:15 describes it. From that peak of pure transcendence, we descend into specifications for acacia wood and dolphin skins. The shift feels almost deflating.

But the Torah is not padding its word count. These chapters encode something essential about what it means to be human and to seek connection with the Divine. We are not angels, and sustained abstraction is not something we can live in for long. We need places and objects and rituals that we can see and touch, structures that meet us in our embodied reality. The question the Mishkan answers is how creatures of flesh and blood maintain a relationship with the Infinite. That question remains as urgent now as it was in the wilderness. The wood and gold may be ancient, but the problem they address is thoroughly modern. The five dimensions of the Mishkan explored below suggest that the exhaustive detail is a curriculum for how embodied creatures learn to hold the sacred.

1. The Spirituality of Aesthetics: Why Beauty Matters

Judaism contains an internal tension here. The same Torah that prohibits graven images commands the construction of an ornate sanctuary featuring golden figures. The Jewish discomfort with lavish religious aesthetics originates in the Second Commandment itself, and the instinct toward restraint runs deep. This suspicion shaped Western culture more broadly through Protestant iconoclasm, but the tension is native to Jewish tradition from the start. Lavish sanctuaries can feel like vanity projects, money that should have gone to the poor spent instead on gilt and marble.

So it’s striking that God’s instructions for the Mishkan read like a request for the most visually magnificent materials available. Exodus 25:3-8 catalogs the contributions, beginning with gold, silver, and copper, then moving through yarns dyed blue, purple, and crimson, fine linen and goat hair, ram skins dyed red and dolphin skins, acacia wood, oil for lighting, spices for incense, and finally lapis lazuli and precious stones for the priestly garments. The Torah is asking for splendor.

The Sefer HaChinuch explains why in Mitzvah 95. Human internal states follow from external stimuli. We are embodied creatures whose emotions respond to what we see and touch. Physical grandeur is necessary to “awe the heart,” to create the conditions under which reverence becomes possible. Thinking your way into wonder doesn’t work; you have to encounter something that evokes it.

Contemporary research on awe confirms this ancient intuition. Dacher Keltner, a psychologist at UC Berkeley, spent years studying what happens when people encounter vast beauty, and his book Awe documents the neurological and behavioral shifts that follow. The ego quiets, prosocial impulses strengthen, and time seems to expand. These are measurable changes in how people think and act after experiences of aesthetic wonder.

This is what Rav Dovid’l Weinberg gets at when he discusses music and beauty in prayer on the 18Forty Podcast. The melody carries meaning the words alone cannot convey, reaching parts of us that rational argument leaves untouched. The Mishkan operated on the same principle. The gold was technology, designed to produce a specific effect on the humans who encountered it. This doesn’t mean every Jewish space must glitter with gold; synagogues inherited a different tradition, and the Mishkan‘s ultimate trajectory was toward internalization. But the principle stands: The brain associates beauty with significance, and the Torah commandment of Hiddur Mitzvah recognizes how we actually work. What standing before something magnificent accomplishes in a moment, abstract theology struggles to achieve at all.

2. The “IKEA Effect” of Spirituality: Value Through Investment

There is a strange choice of verb in the opening instruction. Exodus 25:2 tells Moshe to speak to the Israelites so that they will “take for Me a contribution.” The Hebrew verb is veyikchu, literally “and they shall take,” though some English translations smooth this to “bring.” The choice of verb is precisely what catches the commentators’ attention, because we would expect veyitnu, “to give.” Why would the Torah describe giving as taking?

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks taught that this linguistic reversal reveals something essential about generosity. When we contribute to something larger than ourselves, we expand. The act of giving creates ownership in a way that passive receiving never can. By releasing our resources into a shared project, we acquire a stake in what that project becomes.

Rabbi Sacks elsewhere draws a deeper connection. God created a home for humanity in the world; now humanity creates a home for God in the Mishkan. The parallel is deliberate. God does not need a physical dwelling any more than the Infinite needs furniture. But building on behalf of another creates a relationship. The Mishkan allowed Israel to reciprocate God’s creative generosity, and in that reciprocal act of making, they became bound to what they made.

Behavioral economists have documented this dynamic in controlled settings. Michael Norton, Daniel Mochon, and Dan Ariely published a paper in 2012 called “The IKEA Effect: When Labor Leads to Love,” demonstrating that people value objects significantly more when they have personally invested effort in creating them. The bookshelf you assembled yourself, however imperfectly, matters to you in a way that an identical bookshelf delivered fully built does not. The investment generates the attachment.

The same dynamic operates in communities. Rabbi Dr. Ari Bergmann explores this on the 18Forty Podcast when he discusses the spiritual architecture of release that runs through Jewish life, from shemittah to tzedaka to terumah. Each practice involves letting go of something material, and each transforms our relationship with what remains. The person who has given to build something feels ownership of what was built; the person who merely observes from the sidelines remains a spectator.

Terumah reverses our usual assumption that we must feel inspired before we give. The giving itself creates inspiration. The Israelites who contributed to the Mishkan would travel with it through the wilderness, but more importantly, it would travel within them. We treasure what we have invested ourselves in, and the Mishkan ensured that every contributor would feel the sanctuary was theirs. What we build for God builds us.

3. Structure as Interface

The measurements can seem almost comically specific. Exodus 25:10 gives the Ark’s dimensions with obsessive precision, specifying two and a half cubits long, one and a half cubits wide, one and a half cubits high. These fractional measurements recur throughout the specifications, raising an obvious question about why sacred objects would require such incomplete dimensions.

Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, in his commentary on this verse, finds meaning in the incompleteness these fractions represent. The Ark deliberately avoids whole measurements, signaling that one who approaches Torah can never consider themselves complete. But the precise specifications serve another purpose as well. The Mishkan was never meant to contain God, which nothing can. Humans, being finite, need finite structures to approach what is boundless. The measurements create an interface through which embodied humans can encounter what exceeds all measurement.

This insight connects to broader research on how ritual functions. Adam Seligman and his co-authors argue in Ritual and its Consequences that the boundaries of ritual, however arbitrary they may seem, are precisely what allow participants to inhabit a shared world of meaning. Without structure, significance dissipates, and the limits that feel constraining are actually what hold the experience together.

Chaim Saiman develops a related idea when he discusses how halachic specificity functions as a kind of constitutional framework for Jewish life. The details are the architecture of spiritual experience. A cup needs walls to hold water, and spiritual experience needs the boundaries of defined practice to keep from evaporating into vague sentiment.

Modern seekers often want spirituality without religion, transcendence without the tedium of specific practices. But formlessness is hard for finite creatures to grasp. The Mishkan‘s precise specifications teach that structure enables encounter. This doesn’t mean God can only be found in sacred buildings; the trajectory of Jewish thought, as we’ll see, moves toward the sanctuary of the heart. But even internal encounters require discipline, practice, form. The half-cubits are training in how finite beings approach what has no limit.

4. The Center of Gravity: Intimacy and Relationship

At the center of all these precise specifications sits something unexpected. Exodus 25:20-22 describes the Cherubim that stood atop the Ark, two golden figures with wings spread upward and faces turned toward one another. God’s voice would emerge from the space between them. The innermost point of the sanctuary featured two figures in relationship, oriented toward each other.

The figures might seem strange at first. The same Torah that prohibits graven images places golden statues at the holiest point of the sanctuary. But look at how they’re positioned. The Cherubim face each other, and God’s voice emerges from the space their orientation creates. They don’t depict God. They depict what it looks like when two parties are turned toward one another in relationship. The Talmud describes how their position would shift as a heavenly sign, facing inward when Israel and God were close, turning toward the walls when the relationship grew distant. Anyone who has walked into a room and immediately sensed whether two people are connected or estranged knows this language. The body speaks before words do. The Mishkan placed that truth at its center.

Psychologists have identified something similar in human development. The foundational research on attachment theory by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth demonstrated that children explore the world confidently only when they have a secure base to return to. The parent’s reliable presence enables the child’s freedom to venture outward, because knowing you can come back is what makes leaving possible.

Debbie Stone touches on this dynamic in her 18Forty conversation about teaching prayer. Transmitting connection requires something different than transmitting information. It demands modeling, patience, and presence over time. The Mishkan traveling through the wilderness with Israel functioned as that secure base, the tangible assurance of ongoing relationship. Exodus 40:36-38 describes how the cloud above the Mishkan signaled when to journey and when to rest. The people navigated by relationship, following the presence that traveled with them.

The Mishkan did not primarily house objects. It housed a relationship, and it displayed that relationship’s health for anyone willing to look. The question it poses to us is whether we have structures in our own lives that make the invisible state of our connections visible, and whether we turn toward or away when distance sets in.

5. The Architecture of the Heart: Immanence

A grammatical anomaly in Exodus 25:8 points toward the Mishkan‘s deepest purpose. The verse reads, “And they shall make Me a sanctuary, and I will dwell among them.” In Hebrew, the expected phrasing would be betocho, “within it,” referring to the sanctuary just mentioned. Instead, the text says betocham, “within them,” referring to the people. The dwelling place is the human heart.

Commentators have long noticed this anomaly and developed its theological implications. The physical sanctuary serves as a training ground, teaching embodied creatures to become vessels for the Divine presence. The wood and gold point beyond themselves. Cognitive science offers a framework for understanding why this external-to-internal movement works. In The Meaning of the Body, philosopher Mark Johnson explores how humans comprehend abstract concepts through physical metaphor. We understand containment, proximity, and elevation because we have bodies that experience these things, and we map that embodied knowledge onto abstract domains. We grasp holiness through the language of sacred space; we understand closeness to God through experiences of physical nearness. The Mishkan leveraged this embodied cognition, using tangible structures to shape intangible realities.

Rav Dov Singer describes a similar trajectory in his 18Forty discussion of internalizing prayer. The words begin as external text, spoken by the lips, read from a page. Through repetition and attention, they gradually become internal reality, living in the body instead of merely passing through it. What starts as recitation becomes genuine expression.

The Mishkan‘s ultimate success would be its own obsolescence. The physical structure was meant to train a people to become carriers of the Divine presence themselves. We build with hands and eyes because that is how embodied creatures learn. The gold and silver are scaffolding, necessary during construction but pointing toward something that will eventually stand without them.

The blueprints in Parshat Terumah are construction documents for a soul. The question they pose is whether we are becoming the kind of person in whom holiness can dwell. That project continues long after the acacia wood has returned to dust, and it is why these chapters, with all their seemingly obsolete detail, remain as urgent as ever.

Questions for Reflection

- The IKEA Effect suggests we value what we invest in building. Where in your community involvement are you a spectator rather than a contributor, and how might that be affecting your sense of belonging?

- The Cherubim faced each other when the relationship was healthy and turned away when it was strained. When you feel spiritually distant, does your instinct move you toward connection or toward isolation?

- How do you navigate the tension between beautifying religious practice and financial modesty? When does investment in sacred aesthetics feel like genuine spiritual technology, and when does it feel like excess?

This project is made possible with support from the Simchat Torah Challenge and UJA-Federation of New York. Learn more about the Simchat Torah Challenge and get involved at their website.