Reading Jewish History in the Parsha is a weekly newsletter from 18Forty, where guest writers contribute their insights on Jewish history and its connection to the weekly parsha. Receive this free newsletter every week in your inbox by subscribing here. Questions, comments, or feedback? Email Rivka Bennun Kay at Shabbosreads@18forty.org.

Our world continues to struggle with its demons. It’s hard not to feel that too often, we are left to watch as the world gives into its worst impulses, backslides and takes the cheap way out. If we aren’t careful, a feeling of helplessness can begin to creep into our own lives: What does it matter what I do? How can I help a world that does not know how to face the demons that plague it?

As it turns out, the Jewish People have been facing and besting demons for thousands of years, in the most literal sense. Jewish texts of all types and across the generations discuss these forces in a range of contexts. The rabbis discuss everything from their anatomy to their impact on our lives to methods and spells for mitigating (or even controlling) them. Strikingly, these texts often do not limit themselves to metaphysical discourses or supernatural practices. The engagement with the demonic often raises questions of personal conduct and ethics. To look into the realm of the demonic is also to confront one’s inner demons and to discover how we can overcome them. What can we take from this? In the season of the High Holidays, the time of teshuva, what can we learn about our own spiritual growth from these episodes? We’ll explore below three different encounters that the Jewish People have recorded with demons and try to read them in a new, anthropocentric light, to guide us in becoming better this year.

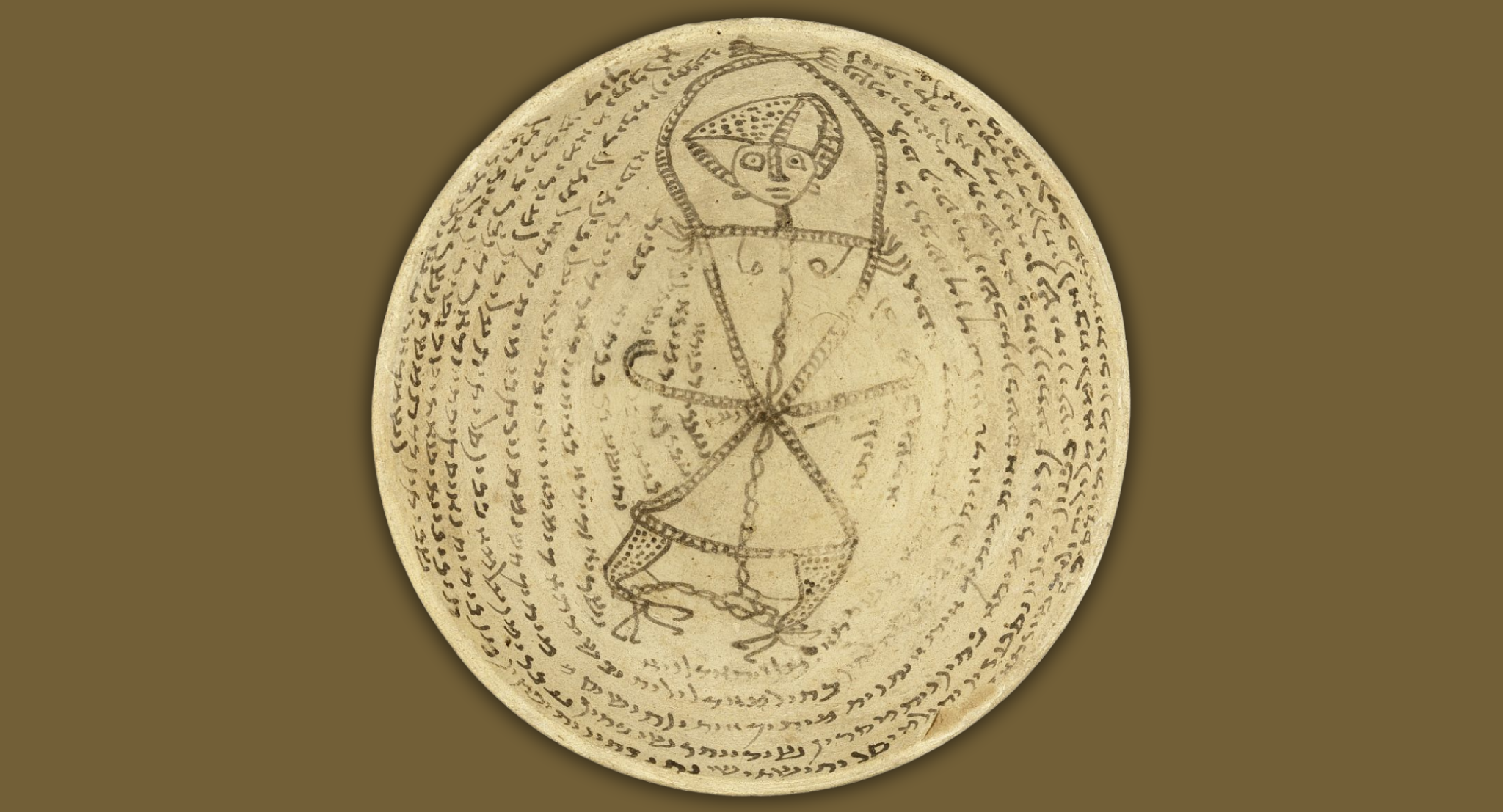

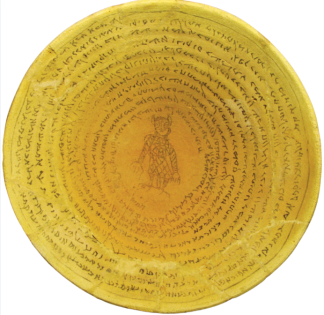

In antiquity, the Jewish People saw demons as a fact of life to be accepted and engaged with. This is not only attested to in the numerous texts which discuss them. A peculiar phenomenon, called “incantation bowls,” is being studied and publicized for the first time. Over 2,000 of these bowls from over a millennium ago survive today. They contain complex formulae which compel demons in a variety of ways: to heal people, to stay away from certain households, or even to pursue and curse enemies. There are even bowls written in the name of Rav Ashi, the famed Talmudic writer and editor. These bowls sometimes even produce images of what the demons they are writing about look like (see the cover of Aramaic Spell Bowls: Jewish Babylonian Aramaic Bowls vol. 2, reproduced below). The text of these bowls varies massively: some of them reproduce rabbinic stories, others utilize Jewish legal formulae, and others still invoke testimonies of mystical experiences. What binds them together despite these differences is the belief that through mental power and focus, even the supernatural and invisible can be bent to our will.

The encounter with the otherworldly ultimately is considered successful or not based on whether it addresses human concerns in the here and now. This is the first approach that we can try to internalize. When confronting something that we want to change about ourselves this upcoming year, sometimes discipline is the best medicine. Setting boundaries and forcing ourselves to think, speak, or act a certain way can set new routines and inculcate new behaviors. Through this, we become master over our demons.

I want to trace two other approaches to facing our demons, both of which happen to be very timely. Perhaps the most prominent is Yom Kippur. The commentators on the Torah are puzzled by the injunction to offer “two goats, one marked for Hashem and the other marked for Azazel” on Yom Kippur. While the goat designated for Hashem is sacrificed in the Temple, the goat marked for Azazel is to be “left standing alive before Hashem, to make expiation with it and to send it off to the wilderness for Azazel.” The Ramban writes, based off the Ibn Ezra in particular, that the offering of the goat is is to the force that “rules over wastelands … and destruction and waste emanate from that power, which in turn is the cause of the stars of the sword, wars, quarrels, wounds, plagues, division and destruction” and which rules over se’irim, goat-like demons of the desert. Importantly, he writes that there is no concern of idolatry in this practice, both because it is explicitly Hashem’s desire for us to do this, and because we do not actually slaughter it, but rather send it into the wilderness.

The Avi Ezer, R. Shlomo haCohen of Lissa, connects the Ibn Ezra’s and Ramban’s comments to the Biblical story of Yaakov and Esav: “This is a hint to Yaakov who sent a gift to Esav, just as we send an offering for recollection and awakening … it also awakens and arouses Yaakov’s submission as he brought this offering to his brother, the blessing he received from his father.” This can be true in an outer and an inner sense. We often avoid facing parts of ourselves that challenge us to avoid the feelings of anger, shame, or disappointment that we know will come as a result. It is easier to conceal them than to confront them. If we can cultivate a sense of openness, gentleness, and humility in how we look inside, we may be able to be braver than before and to take an important step on the road to teshuva.

Demons also feature in this week’s parsha, Parshat Ha’azinu. Ha’azinu is a quick review of all of biblical Jewish history by Moshe and Yehoshua. This extends all the way back to Adam and Noach, runs through the Exodus from Egypt and Bnei Yisrael traveling through the desert, and even looks to the future to warn the people of the consequences if they stray from the Torah’s path. Moshe describes in detail what will be sent against them: “wasting famine, ravaging plague [lechimei reshef], deadly pestilence [ketev meriri], and fanged beasts will I let loose against them, with venomous creepers in dust.” Some of these phrases were understood in the Talmud as proper names of demons rather than descriptions of punishments: “[the word] reshef refers to none other than demons.” Rashi writes there that this claim is bolstered by the fact that reshef is mentioned in the same verse as ketev meriri, “the name of a demon” as well. The Talmud explains elsewhere that ketev meriri lurks in the shadow and becomes especially active in the Jewish month of Tammuz in the lead up to the period of time where we mourn the Temple’s destruction.

A midrash gives us a fuller picture of how ketev meriri looks and what it likes to do. One rabbi describes it as “completely full of eyes, scales, and hair,” while another claims that “one eye is situated on its heart, and anyone who sees it falls and dies.” Most relevant for our purposes, however, is the incident described in the Midrash by Rabbi Abahu:

“He saw a certain person who was carrying a stick and going to strike another person. He saw a demon standing behind him carrying an iron rod. He stood and called out to him, saying to him: ‘Why do you seek to kill your counterpart?’ He said to him: ‘Can a person kill another with this?’ He said to him: ‘There is a demon standing behind him that is carrying an iron rod. You strike him with this and it will strike him with that and he will die.’”

The rabbis legislated based on this that in the afternoon, when ketev meriri is strongest, children should be dismissed from school, lest someone hit them and ketev meriri strengthen the blow. This idea is even brought down in the Shulchan Aruch, the essential 16th-century codex of Jewish law. This traces a different response to facing demons: Become their opposite. When cruelty rises in the world, we become more compassionate in our conduct with others. The more we can try to be patient, understanding, and flexible, the less power our own demons will hold over us. If Azazel calls us to soften our approach when looking inward, ketev meriri is an invitation for the same softness when looking outward.

For most of us, the demonic is not something we engage with on a daily (or even yearly!) basis. But we needn’t become too superstitious to open ourselves up to what our tradition offers us with these stories and practices. We should be blessed with a year to succeed in doing the teshuva that we most need, even where it’s difficult, and in doing so, to leave behind the demons of the past and focus solely on the divine through the coming of Moshiach!