Many Jews today feel a persistent sense of dislocation: a longing for connection to tradition, meaning, and justice, coupled with the recognition that these things often feel distant or unattainable. How does one engage with Jewish identity and spirituality when the world seems indifferent, divine guidance is hidden, and answers are rarely clear?

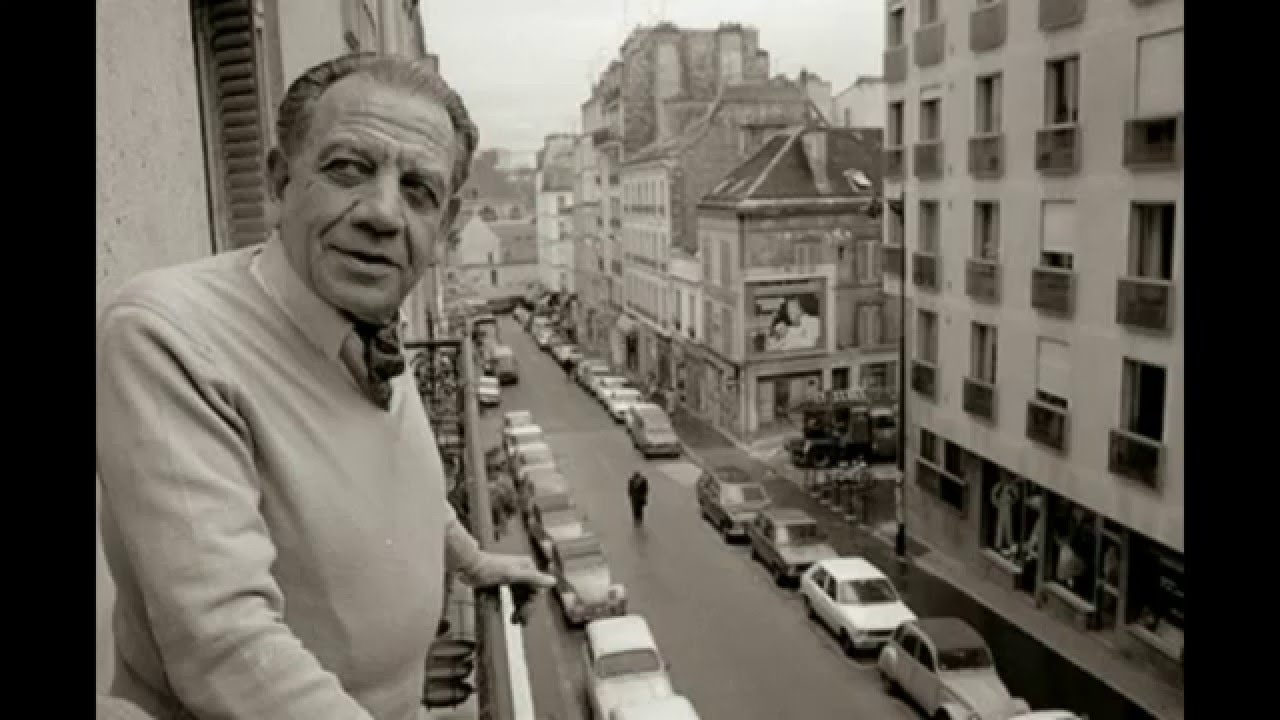

This tension—between yearning for understanding and facing silence—captures the heart of both modern Jewish life and Franz Kafka’s writing. Kafka, one of the most enigmatic voices in literature, offers Jewish readers more than haunting fiction—he offers a mirror. His work reflects estrangement, unanswered questions, and the elusive sense of justice that have long defined the Jewish experience. If Jewish tradition thrives on dialogue with God, Torah, and history, Kafka’s stories dramatize the very silence that confronts us, demanding reflection, struggle, and engagement.

Kafka was born into a German-speaking Jewish family in Prague, caught in a web of Czech nationalism, German culture, and Jewish identity. This fractured belonging marked him. In The Trial, Josef K. is arrested “without having done anything wrong” and subjected to a system whose laws he can neither see nor understand. Kafka writes: “It’s characteristic of this judicial system that one is condemned not only when innocent but also in ignorance.” Beyond a mere description of bureaucratic nightmare, this echoes the Jewish experience in exile, where foreign systems judged Jews as guilty simply for existing. Kafka’s courtroom becomes a modern midrash on that hostility—a world where justice is hidden, but accusation never sleeps.

Yet what makes Kafka Jewishly indispensable is not only his reflection of persecution, but his spiritual daring. In The Castle, his protagonist struggles endlessly to gain access to an unreachable authority. The narrative ends with no resolution, only yearning. Kafka once wrote in his diaries: “The Messiah will come only when he is no longer necessary; he will come only after his arrival; he will come, not on the last day, but on the very last.” This paradox, both despairing and hopeful, resonates with the Jewish idea of redemption as a process that cannot be rushed but must always be yearned for. The Zohar describes exile as “a night that never ends until the dawn of redemption” (Zohar I:170b). Kafka’s endless night is not foreign to Jewish tradition—it is its modern expression.

Jewish readers should also recognize in Kafka the echo of hester panim—the hiding of God’s face. The Torah declares: “I will surely hide My face on that day” (Deut. 31:18). Maybe this could be understood not as abandonment but as a trial of faith, a demand that Israel seek God even when He seems absent. Kafka’s world is drenched in that hiddenness. Though God is never named, His absence is palpable. The Hasidic master, Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, taught: “Even in the concealment within the concealment, God is still present” (Likkutei Moharan I:56). Reading Kafka through that lens transforms despair into spiritual urgency: His silences are not empty, but charged with the question of how to live and seek in spite of them.

Language itself is another Jewish thread in Kafka. His stories resist closure, bristling with symbols that demand rereading. The Metamorphosis opens with Gregor Samsa’s shocking transformation: “When Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a monstrous insect.” This jarring sentence is never explained. Like a cryptic line of Torah, it must be turned over endlessly. Kafka’s texts function similarly—not by providing answers, but by opening interpretive space. For Jewish readers, they model a form of modern midrash, where meaning is not given but pursued.

Importantly, Kafka embodies the modern Jew’s estrangement from tradition. He was not observant, but he never escaped Judaism. He studied Hebrew, attended Yiddish theater, and wrote of his longing for a Jewish home he could not find. In his diaries, he confessed: “What have I in common with Jews? I have hardly anything in common with myself.” That self-estrangement captures what many Jews today feel: not at home in religious life, yet unable to sever the pull of Jewish identity. Kafka does not resolve this tension—he lives inside it. In this way, he becomes a companion for Jews navigating their own ambivalence.

To read Kafka is thus to participate in a kind of modern Jewish study session. His works raise the same questions that animate Torah and Talmud: What is justice? Where is God in a world of suffering? How does one live when meaning is obscured? Kafka does not give answers—but neither do our most sacred texts. The Talmud famously concludes a fierce debate with the words: “These and those are the words of the living God” (Eruvin 13b). Truth, in Judaism, often lies not in solving the problem but in wrestling with it. Kafka’s gift is to keep us living in that place of tension.

Jews should read Kafka not because he comforts us, but because he unsettles us. His writing reflects the fractures of exile, the hiddenness of God, and the ceaseless search for justice. He transforms alienation into an arena for meaning-making, silence into a site for dialogue. In doing so, he joins the lineage of Jewish prophets and poets—not proclaiming answers, but holding open the questions.

As Kafka himself wrote: “A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us.” For Jews, still navigating exile, assimilation, and divine silence, his words cut open the frozen spaces of our experience—making room for struggle, and therefore, for life.