I Read This Over Shabbos is a weekly newsletter from Rivka Bennun Kay about Jewish book culture, book recommendations, and modern ideas. Receive this free newsletter every week in your inbox by subscribing here. Questions, comments, or feedback? Email Rivka at Shabbosreads@18forty.org.

I’m not necessarily a fast reader. Just as often as I’ll finish a book in a weekend, I’ll spread one out over an entire year. This is just one more reason why 19 Kislev—which begins Monday night—is one of my favorite holidays, as the annual cycle for reading both the Tanya and Hayom Yom starts over.

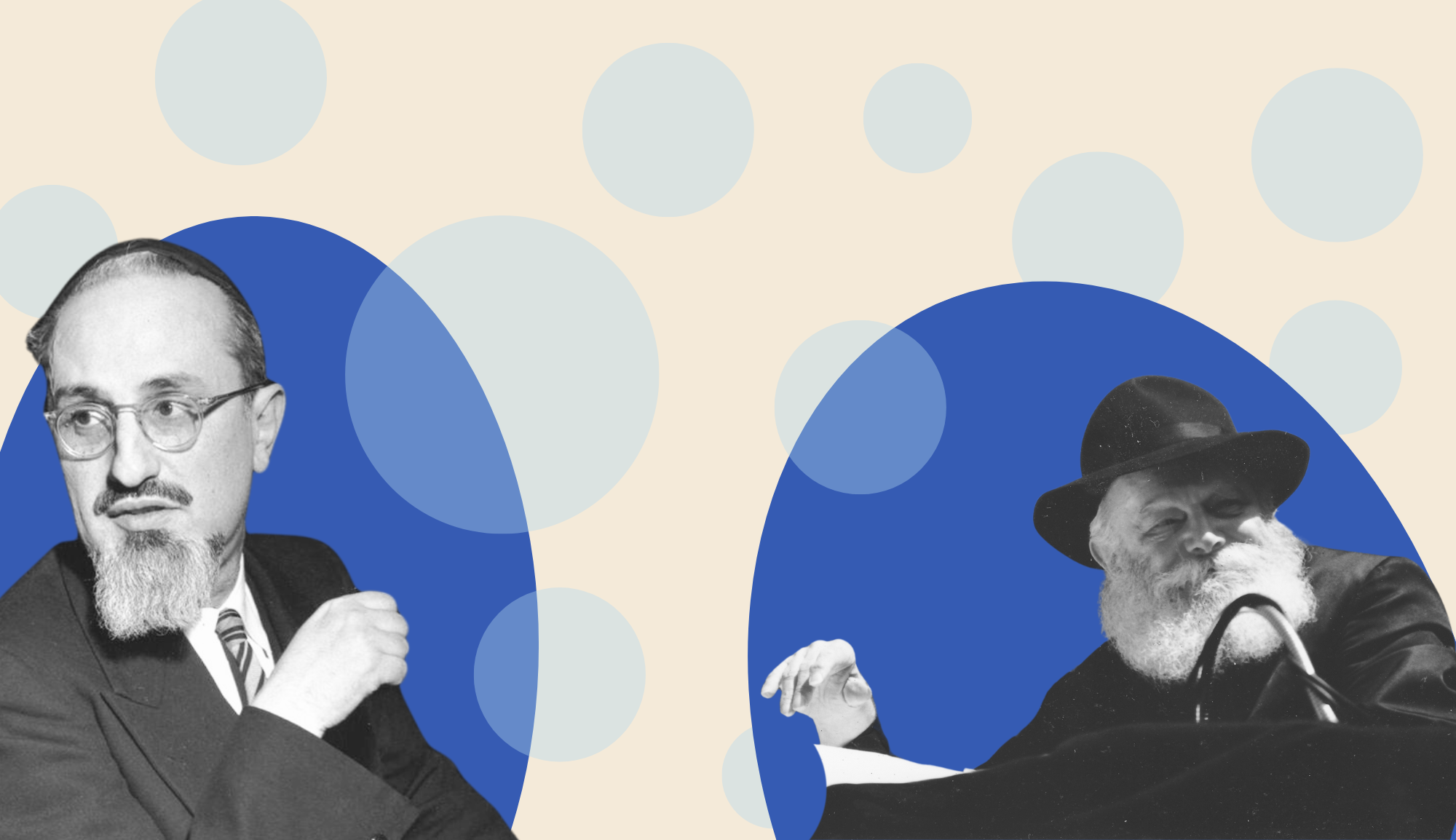

Yud-Tes Kislev, if you’re unfamiliar, is called “the Rosh Hashanah of Chassidism.” It’s the yahrzeit of the Maggid of Mezritch, the principal disciple of the Baal Shem Tov and the figure from whom most subsequent Hasidic sects sprouted. It’s also the date the Baal HaTanya was first released from Russian prison.

For these reasons, we learn in the first entry of Hayom Yom (a book comprising Chabad teachings and customs compiled by Lubavitcher Rebbe) that 19 Kislev is “a day of farbrengen and good resolutions towards establishing times to study the revealed Torah and Chassidus publicly.”

Customarily, Gemara sections are apportioned throughout the community so the entire Talmud can be collectively completed in the coming year. Plus—and this is my favorite part—we begin reading the Tanya all over again, a small section each day for the next year.

When you get to Day 3 of the Tanya cycle (in a non–leap year), you find out the Tanya was written because the Alter Rebbe could no longer possibly personally meet with all of his followers.

“Rabbi Schneur Zalman actually had a massive problem,” Rabbi Eli Rubin said on The Podcast of Jewish Ideas. “Because … he was so sought-after, he didn’t have enough time to offer counsel to all the people who were seeking it.”

“Usually, when you read a book, it’s not by somebody who knows you. But I’m writing this having sat with you all,” Rabbi Rubin said, explaining the Alter Rebbe’s perspective. “I’ve heard all the questions a hundred times already … If you have a question, it’s in this book.”

As Rabbi Joey Rosenfeld put it on the Homesick for Lubavitch podcast: “I’m giving you a book that will stand in the place of yechidus.”

The past year has been my first time finishing the entire Tanya straight through, and I found that this daily audience with the Alter Rebbe has given me X-ray vision into my own soul, and into the souls of others. When I felt slighted by someone, I learned to see them not as malicious, but as letting their baser impulses overpower their upper ones. More importantly, I learned to sense when the same thing was happening in myself.

I learned from this book that’s also a Rebbe—tailor-made to stand in place of getting to meet with him—that we ourselves are the battleground fought for between the animal soul and the Godly soul. In Chapter 32, the “heart of Tanya” (32 being the numerical value for lev), I learned that the result of victory of the Godly soul over the animal soul is loving one’s fellow as oneself.

Perhaps most importantly, in Chapter 36, I learned the purpose of creation: for God to have a dwelling place down below.

In that chapter, the Baal HaTanya drops the dark truth that “[This world] is the lowest in degree; there is none lower than it in terms of concealment of His light, and no world compares with it for doubled and redoubled darkness; nowhere is G‑d’s light as hidden as in this world.”

However, we’re told that’s specifically the reason why God wants to be revealed here:

The purpose of the Hishtalshelut [the Kabbalistic system of descending worlds] is this world, for such was His will—that He find it pleasurable when the sitra achara is subjugated to holiness, and the darkness of kelipah is transformed into holy light, so that in the place of the darkness and sitra achara prevailing throughout this world, the Ein Sof—light of God—will shine forth with greater strength and intensity, and with the superior quality of light that emerges from the darkness.

Learning the Tanya this year has made it the most transformative year of my life, but it by no means has been the best. The Tanya teaches us to deal with depression, financial problems, interpersonal conflict, struggles in our spiritual lives, and even the question of what to eat and why.

It’s intended not for those free from such problems, and it’s not for those looking to escape them, either. The Tanya is for those who are faced with unavoidable challenges that get in the way of our ideal lives and ask: What now? In short, it’s for everyone. It’s for those of us who need a Rebbe, but have access instead to a book. This yontif, I invite you to open it for yourself.