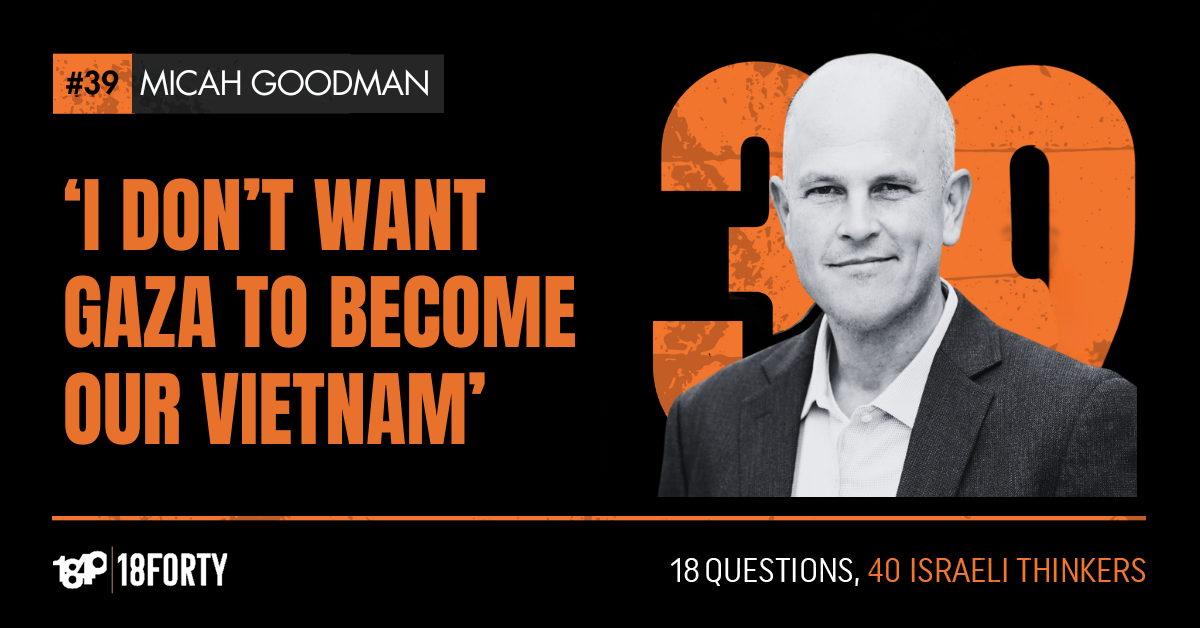

Micah Goodman: ‘I don’t want Gaza to become our Vietnam’

Micah Goodman doesn’t think Palestinian-Israeli peace will happen within his lifetime. But he’s still a hopeful person.

Summary

Micah Goodman doesn’t think Palestinian-Israeli peace will happen within his lifetime. But he’s still a hopeful person.

Named by the Jerusalem Post as one of the 50 most influential Jews, Micah is a public intellectual, writer, and author whose voice is central to the moral, political, and religious debates raging within Israel.

He is the author of several best-selling books — including The Wondering Jew, Catch 67, The Dream of the Kuzari, and The Last Words of Moses — and co-host of the popular Israeli podcast Mifleget Hamachshavot.

Now, he joins us to answer 18 questions on criticizing Israel, resettling Gaza, and Jewish democracy.

This interview was recorded on July 6.

Transcripts are produced by Sofer.ai and lightly edited—please excuse any imperfections.

Sruli Fruchter: Do you think peace between Israelis and Palestinians will happen within your lifetime?

Micah Goodman: No.

Sruli Fruchter: Why?

Micah Goodman: I don’t know how long I’m going to live for, but a lifetime. I want to change my answer. In the foreseeable future, no.

Why? Because I think it’s too much to ask for Palestinians. I don’t blame the Palestinians. It’s too much to ask from them. Asking the Palestinians to recognize the existence of a Jewish state in this land is actually asking them two different things.

Hi, I’m Micha Goodman. I write books. I think a lot about Israeli contemporary issues, and this is 18 Questions for the Israeli Thinkers from 18Forty.

Sruli Fruchter: From 18Forty, this is 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers, and I’m your host, Sruli Fruchter.

18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers is a podcast that interviews Israel’s leading voices to explore those critical questions people are having today on Zionism, Israel’s Hamas War, democracy, morality, Judaism, peace, Israel’s future, and so much more. Every week, we introduce you to fresh perspectives and challenging ideas about Israel from across the political spectrum that you won’t find anywhere else. So, if you’re the kind of person who wants to learn, understand, and dive deeper into Israel, then join us on our journey as we pose 18 pressing questions to the 40 Israeli journalists, scholars, and religious thinkers you need to hear from today. My favorite interviews are the ones where I have to tell the guest early on, and it’s probably edited out so you will never actually hear it, that they need to try to be more concise and brief with their answers because we have time constraints.

I find that those interviews are filled with so much substance and depth that it really exemplifies our mission and what we always say that our interviews are not supposed to cover every single nuance of every single question that we ask, but are meant to be the starting point for how our listeners engage and build a relationship to the guest that we bring on. And with today’s guest, who was highly recommended from our very first day of launching this podcast, Micah Goodman was no exception. Micah is a writer, thinker, and public intellectual in Israel, who was named by the Jerusalem Post as one of the 50 most influential Jews in 2017, and is the author of several best-selling books, including The Dream of the Kuzari, The Secrets of the Guide of the Perplexed, The Wandering Jew, Catch 67, The Attention Revolution, and The Last Words of Moses. These span religion, politics, and history, which in many ways exemplifies the diversity of thought that Micah tries to embrace.

He co-hosts the popular Israeli podcast, Mifleget Machshavot, the party of thoughts, with Efrat Shapira Rosenberg and is one of Israel’s most highly respected thinkers and speakers on all things politics, society, and the Jewish future. This was such a delightful interview for so many reasons. If there is any thinker who cannot be understood in one interview, it is Micha Goodman. And so I really encourage you to search out his thought, search out more about him and how he thinks from wherever you can find his speeches, podcasts, articles, talks, books, and much else.

And so before we head into the podcast, Micha is our 39th Israeli thinker, which means next week is the 40th Israeli thinker for 18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers. If you have questions you want us to ask, or guests that you want us to feature, you are too late. I already have our final guest and I am not backing away from him. This has been a really incredible journey, and I want to hear from you.

Who were your favorite guests? Which was your favorite episode, your most upsetting episode? The moments that really struck you, that resonated with you. We always want to elevate the voices of our listening community, and it is no different with this podcast. So, without further ado, here is 18 questions with Micha Goodman. So, we’ll begin where we always do.

As an Israeli and as a Jew, how are you feeling at this moment in Israeli history?

Micah Goodman: Well, this podcast is recorded about a few days after the end of the 12 day war. So it’s quite a moment. It’s a real moment, and it’s hard to know what moment we’re in now. But it feels like this might be a six-day war moment, a moment that changed the Middle East and changed Israeli history.

And as a person that’s trying to observe history while it’s happening, it’s impossible to see history while it’s happening. I find this moment exciting, terrifying, and definitely with a lot of promise and definitely very interesting.

Sruli Fruchter: Interesting how?

Micah Goodman: It’s just interesting. The world is becoming very interesting.

Israel is interesting. The world is interesting. The Middle East is interesting. It’s a pregnant moment.

Now, I like that metaphor pregnant because I’m Israeli, we don’t, it’s not an Israeli moment, ha’rega she’hu be’herayon. It’s not an Israeli metaphor. But in the idea that a moment can be pregnant, but you don’t know with what. And this is a pregnant moment.

Now, will this lead to more peace in the Middle East? Or more importantly, will this moment lead to more peace within Israel, between Israelis? These are very big questions.

Sruli Fruchter: Do you think it will?

Micah Goodman: I think it could go in many directions. That’s what makes this moment very interesting.

Sruli Fruchter: What does it depend on?

Micah Goodman: Meaning what it’s depend if they’ll have peace in the more peace…

Sruli Fruchter: No, you said that it can go in different directions, this this moment’s almost like at a at a fork in the road. So what does that depend on?

Micah Goodman: Well, I think this has been a real Israeli victory. This war has been an Israeli victory.

Sruli Fruchter: Which war? Against Iran or against Hamas?

Micah Goodman: Well, the war against Iran has been an incredible Israeli victory.

Iran has tried to build what the octopus, a network of terrorist proxies surrounding Israel, so that in one day when Israel is surrounded and isolated, it could press a button that unites all the fronts and destroys Israel. That was the grand plan of Iran. Now, obviously we were surprised in October 7th, but I think in the past few months, we realized we were surprised again. And here’s the deeper surprise.

The deeper surprise is that we start to realize that what would have happened if Hezbollah would have attacked Israel all in, full-blown in October 7th? What would have happened if that, and while they’re attacking us from the north, doing to us much more than Hamas, the Radwan forces were doing to us in the south, while Israel is being, its south is being conquered, its north is being conquered, we’re also targeted with thousands of accurate missiles on strategic sites. The electricity, the central command locations, and Israel goes into chaos. What happens? The most probable scenario that at this situation, Palestinians from the West Bank or Judea and Samaria would see that, feel that Israel is starting to go down, and as a Shabak person told me, that’s the moment they join. And the violent parts of Israeli Arabs, the violent parts, will join.

So you can imagine a scenario, a very high scenario that has more than 50% probability of complete chaos that could lead to complete loss of control of Israel over the situation. Meaning, we were under existential threat and here’s the thing, we didn’t know it. I mean, many Israelis knew that our neighbors want to destroy Israel. Some of us knew that they might have the guts to attack Israel.

But I think none of us really knew that they actually have the capability.

Sruli Fruchter: Did you know it?

Micah Goodman: To do it. I didn’t know it. That’s why I called it the second surprise.

The first surprise is that they attacked us. The second surprise starts kicking in throughout the war when you realize, oh my God. It turns out that we were under existential threat and we didn’t know it. Israel was beneath a volcano.

We were building our beautiful lives, which means every company in Israel is overvalued. Every, the stock market of every company was overvalued. The rational decisions that people to make aliyah was not, like, we were under real existential threat and we didn’t know it. So it turns out that this war dismantled a threat that we didn’t really knew.

I mean, what did, did some people in the Israeli intelligence, maybe some people theoretically knew it, but October 7th made that, we could now imagine the real threat. So what happened in this war is we dismantled an existential threat, not a potential. The Iran nuclear is a potential existential threat, but in October 7th, we were under real existential threat. Now, we dismantled that threat and the whole idea of surrounding Israel with proxies.

And what Israel did was the following. Sinwar had had a, he had a double gamble. He bet that Israel is very divided and that the Iran front of proxies is very united. So his bet was, he’ll attack Israel because it was 2023, judicial reform and all that.

We were very divided. He’ll attack us and we’ll like collapse into our own divisions. That was bet number one. Bet number two is, when he’ll attack us, Hezbollah will join.

The proxies in Iraq will join. The Palestinians in Yehuda ve’Shomron or West Bank, they’ll join. Iran eventually will join. And what happened was he got his two gambles wrong, his two bets were wrong.

He attacked us and Israel didn’t collapse into its divisions, it united. And their front did not unite. Israel had the privilege to fight Hamas without Hezbollah coming in all in, and then to fight Hezbollah without Iran saving Hezbollah, and then to attack Iran without Hezbollah helping out Iran. So we got to fight this, fight this one by one.

And that’s by the way why we had

Sruli Fruchter: significant victory. So while, so this is so he got his boat. We were, he was betting on our division and their unity. What really happened is that we’re much more united than they imagined, and they are, it turns out that they’re more divided, have less solidarity between themselves than, than we saw.

So that was stage one of the war. The reason why I’m hopeful now is because we might moving into stage two.

Micah Goodman: So I actually want to talk about the one of the wars that’s ongoing, which is the Israel-Hamas war, the Israel-Hamas war.

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah.

Micah Goodman: What do you think has been Israel’s greatest success and greatest mistake?

Sruli Fruchter: The greatest success is that we knocked out all their leaders.

Micah Goodman: Mhm.

Sruli Fruchter: That the whole leadership of Hizballah is gone.

Micah Goodman: For for Hamas specifically?

Sruli Fruchter: Hamas specifically, yeah.

You know…

Micah Goodman: I mean you said Hizballah I just want to…

Sruli Fruchter: Oh sorry, sorry, yeah.

Micah Goodman: I didn’t know if that was a mis-speak.

Sruli Fruchter: You know, Issa, Randur, Def, Sinwar one, Sinwar two. We knocked down their leadership, which is tremendous achievement of the Israeli intelligence, military intelligence and Shabak and our operational forces. I don’t really know how to measure that war. It’s an impossible.

This war, it was designed as a tragedy. Hamas designed the war in Gaza as a tragedy. When I say a tragedy, it means creating a situation where there is only bad options, where I think the way Hamas understood this war is the following, the way it designed this war. There’s an Israeli writer and thinker called Guy.

He wrote a book called Tzva High-tech v’Tzva Parashim. Guy Hazut.

Micah Goodman: Mhm.

Sruli Fruchter: Tzva…

Micah Goodman: Oh, I’ve heard of him.

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah, you heard, yeah. He wrote a great book, Tzva High-tech, Tzva Parashim, a great analysis of of the, about of the weaknesses of the Israeli military.

Micah Goodman: Uh-huh.

Sruli Fruchter: And he says there actually two are, so I won’t go into his thesis, but he has this interesting description of the evolution of the Israeli of of the enemies of Israel. And the enemies of Israel had the vision that we need to destroy Israel. Israel is foreign to this neighborhood, to the Middle East. We have to push them out.

And their vision was that in stage one, our standing armies, the Egyptian standing army, the Syrian standing army, support from Iraq, from Saudi, the Jordanians, together we could just attack Israel and destroy Israel. And it was tried in ’48, ’47, ’48 and ’67, and I don’t want to go into ’56 is different story, and ’73, and it failed and it failed and it failed. And the attempt of standing armies to destroy the Israeli army and then to destroy Israel and to erase the presence of Zionists in the Middle East, that failed from that technique. So then…

Micah Goodman: You see this as relevant to the greatest mistake or the greatest success for the war?

Sruli Fruchter: Oh, I’m getting there. I’m getting there. I want to build why it’s a tragedy.

Micah Goodman: Yeah, no please, build it, build it.

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah. So, but when that failed, in parallel, there was always like terrorist attacks. Terrorist attacks were the attempt to weaken Israel. With standing armies, we’ll destroy Israel, right? But then strategy number two came in where terrorism became not the side show, but the main show.

And that’s Iran’s strategy. And Iran’s strategy, Qasem Soleimani specifically from the IRGC, they had this very interesting idea of, well if we have if we tried to to to to hurt Israel through armies and through terrorism, let’s unite the first two stages: an army of terrorists. Stage one and stage two combined. Now, an army of terrorists, because what terrorism does, it attacks civilians and then it hides among civilians.

So it’s unethical offense because they attack civilians and it’s unethical defense because they hide among between civilians. But the startup of an army of terrorists that is, besides ISIS, it’s it has no real precedent because an army is supposed to protect civilians, and here we have real armies with 40,000 soldiers, let’s say if you were talking about Hizballah or or Radwan like real divisions with a structure and command and intelligence and and a certain arm of drones and like a real army, but not an army that protects civilians, an army that as an army is protected by civilians. So this vicious startup of combining army and terrorism, creating an army of terrorists was designed to create a tragedy and here’s the tragedy. This is how Hamas designed the war to begin with.

In October 7th us, and then it goes and hides beneath civilians in the undergrounds of Gaza, right? Now, and they had known something. Israel has two bad options. Bad option number one is not to attack Hamas, which means Hamas developed how to do the perfect murder. You could murder and get away with it if you hide beneath civilians.

Option number two is to destroy Hamas, which means you have to cut through civilians.

Micah Goodman: Mhm.

Sruli Fruchter: Morally, they’re both bad options, which is a tragedy. Israel did not have to choose, we didn’t when we chose to destroy Hamas, we didn’t choose the bad option over the good option.

We chose the bad option over the worse option. That’s what we did. That’s why it’s a tragedy. But the way it was designed by Hamas is the following, that and Hamas understood something about asymmetric war.

legitimacy. And that is, let’s say a war is a car and victory is the destination, and the fuel, the gas tank is international legitimacy. And while you’re driving to your destination, you’re running out of legitimacy, you’re running out of gas. Like while we’re trying to destroy Hamas, we have to cut through civilians.

And that’s ruining the legitimacy for the war.

Micah Goodman: So is this a mistake on Israel’s part?

Sruli Fruchter: No, it’s not a mistake, it’s a tragedy designed by Hamas. And here’s the big question, what will happen first? Will we reach our destination before we run out of gas? Or will we run out of gas before we reach destination? And Hamas’s whole idea was that Israel will run out of legitimacy before destroying Hamas.

Micah Goodman: So I have I have two questions.

One of them is

Sruli Fruchter: So it was designed as a tragedy.

Micah Goodman: So I have two questions. One of them is, one of them is on what you’re talking about, and the other one is trying to press you a little bit more on about what’s a mistake that Israel has made. Meaning because you’re describing what you said as the greatest tragedy, not necessarily Israel’s greatest mistake in the war.

I guess I’ll start there and then I’ll follow up with with the content of what you’re describing now. Actually, we’ll do the reverse. Meaning what I what I find interesting about what you’re saying is you’re setting up a binary where either Israel totally neglects Hamas, or they entirely go after Hamas. And in that binary, either civilians are totally, totally unharmed, or civilians are totally harmed.

But hasn’t the international community and many reporters and journalists also kind of acknowledged a middle ground where the legitimacy and the sense of blame on Israel has changed over the last 1.75 years? That where Israel is today in going after Hamas and the civilian casualties is not necessarily where it was one year ago. Meaning there is a middle ground where Israel can go after Hamas and then at the same time have to recognize when is the limits of civilian casualties beyond what the actual gain is in military feat.

Sruli Fruchter: So so so that’s a big question. I would say, I kind of forget timing, okay? But when did we start Malkivot Gideon?

Micah Goodman: I’m not sure.

Sruli Fruchter: I’m not sure.

Micah Goodman: I think like months.

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah. So, question mark for the audience.

Now, I think a better idea for Israel was, is that the way this government understood the relationship between liberating, bringing home our brothers from Gaza, and destroying Hamas.

Micah Goodman: To your soldiers or the chatufim?

Sruli Fruchter: The chatufim, my brothers. Chatufim.

Micah Goodman: Okay.

And bringing back the the the hostages, and bringing back and destroying Hamas.

Sruli Fruchter: The way they managed, I think at one point, this is like maybe, I forget the timing, maybe three, four months ago after the first ceasefire was after the last deal was over, it went into the Gideon, Malkivot Gideon operation.

Micah Goodman: Gideon’s chariot, yeah.

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah.

I think at that point, after we dismantled 24 battalions of Hamas, and destroyed their leadership, and hit their infrastructure so powerfully, that was a moment to bring back the chatufim. I think that was a mistake. And I’ll try to explain why. Think about it.

What what would have happened if Hassan Nasrallah would have had four hostages with him in the bunker in the Dahieh in the south of Beirut? What would have happened? I think he would have been alive today. You agree with me?

Micah Goodman: I’m not sure.

Sruli Fruchter: I think he would have been alive. I think if he had four of our hostages with him in the in the bunker, I think he was alive.

And you know what, if he had 10 hostages, do you agree he was alive?

Micah Goodman: I I I don’t know. I have to I guess I have to let your side get the spotlight for this interview.

Sruli Fruchter: I think Nasrallah would have been alive today. And that’s, that’s an interesting thought.

Micah Goodman: Because one of the reasons… But do we have actual knowledge about how the chatufim factor in to, I mean, there have been hostages who have have been killed in airstrikes.

Sruli Fruchter: Oh yeah, yeah. Yes, yes.

But the way when the way our army works, it maps out where it thinks high probability of chatufim.

Micah Goodman: Mm-hmm.

Sruli Fruchter: Of our hostages. And it creates, and then it measures a few kilometers from those points and it says, okay, this is an area where we’re very, very careful, where we don’t touch.

So which means, and I think they have different ways to to to measure probability and distances. Which means we’re very, very careful where there is chatufim, where there’s hostages. Which means that our ability to dismantle Hamas is very limited because we we know that we have hostages there. So imagine the following scenario.

We bring the hostages home. And then, a year from now, a year and a half from now, in a surprise attack, we hit Hamas. Let them guard all the tunnels, we hit Hamas. Then you hit Hamas when the Israel is united behind this war, and we’re not limited by our hostages.

Micah Goodman: Mm-hmm.

Sruli Fruchter: Now, this war if it continues is a problematic war, because Israel’s not united behind this war at this stage, and Israel doesn’t know how to win wars that Israelis don’t stand united behind. Look at Lebanon One for example, and the 82 version of Lebanon, and we have the chatufim. So I think bringing the hostages back home is not instead of victory and dismantling Hamas, it’s a precondition for victory in dismantling Hamas.

But the difference is that we have to will take time.

Micah Goodman: And that was a mistake on Israel’s part in the war.

Sruli Fruchter: So that was a big I think that that that wasn’t handled the right way. The reason is, the reason why for that mistake is that many Israelis want victory now.

And the only way to destroy Hamas is to bring the hostages home, and then victory in a year, year and a half, two years from now, or three, I don’t know whatever, whatever it is. So just like the left got it wrong in the 90s when in the 80s, the 90s, when it says peace now. The only peace that’s possible is a peace that’s in the future. I think this government got it wrong when it said victory now, victory over Hamas now.

The only victory, the real victory that’s possible is a victory that takes a long longer time to achieve.

Micah Goodman: So, I want to shift our conversation a little bit and ask more personally, how have your religious views changed since October 7th?

Sruli Fruchter: I’ll be honest, they didn’t change.

Micah Goodman: What do you mean?

Sruli Fruchter: They didn’t change because, well, you could say I’m Maimonidean in my theology. Which means, I think in the deepest sense, that we are commanded by God to hold on to ignorance regarding God.

So, if anybody says, okay, well, how, let’s let’s see. On the one hand, how did October 7th happen? How did bad things happen to good people? How can God do that? Like, that kind of a question, that’s like, that assumes that you have knowledge about God. There’s certain things that God doesn’t do, and he wasn’t and he wasn’t supposed to do this. Well, I I don’t know anything about God.

I don’t know how God, I have no idea how God works. And then some people say, wow, the miracle of the 12-day war. We must have done, I have no idea how God works. So, so I think that the way Rambam understands monotheism is is like this.

There’s, the way I think Rambam understands religion is the following. There’s two versions of religion. In Rambam was very judgmental. There’s a more distorted version of religion, and then there is the real version of religion.

This is my modern speak judgmentally, okay? And he says, the distorted version of religion is the thought is is that religion is there to offer you comfort, to give you a narrative, to give you explanation, to liberate you from the anxiety that comes from uncertainty. Okay? So, but the best form of religion is not about calming your uncertainty. It’s not about giving you the illusion of control and certainty, but it’s about training your mind to accept uncertainty. And we’re living in a world with radical uncertainty.

In The Guide for the Perplexed, the guide has three parts and part one, chapter 32, he says, Rabbi Akiva, the great scholar from the Mishna, it says that in Masechet Chagiga, in tractate Chagiga, he enters the pardes. Now the pardes is like, according to not Rambam, this is the area of like divine knowledge. And it says hu nichnas b’shalom v’yatza b’shalom. He entered, I guess, you might say, with peace and and and exited with peace.

That would be a translation. But Rambam understands it differently. Shalom milshon shleimut. Wholeness or perfection.

Wholeness or perfection. So he asks, what was Rabbi Akiva’s quality that he reached human perfection? And his answer is, I’m quoting now from the Hebrew translation, I don’t know how it’s translated to English. She’ne’etzar b’mekom ha’safek.

Micah Goodman: That he like stopped or…

Sruli Fruchter: He stopped in the location of uncertainty. Imagine a meter over a meter, like a yard over a yard, a square yard of uncertainty and to stand there where you don’t know. So Rabbi Akiva’s perfection is not that he reached the truth, but he reached the moment that he knew that he doesn’t know the truth. If God is transcendent and beyond our understanding, and God is somehow governing what’s happening, it means that we live in a radical uncertainty.

And radical uncertainty means, so so ever since October 7th, I think it didn’t change. I didn’t have any theological…

Micah Goodman: It may have brought it to life in a…

Sruli Fruchter: But it brought the idea that that we have this tradition that’s training our mind to live with mystery, to live with enigma, to live in uncertainty that became more important than before.

Micah Goodman: That’s very beautiful, and we’re probably going to come back to that with a later question. But I’m tempted, the problem I always run into is that we have 18 questions and only so much time, but amazing. Asking, staying in the in the personal realm for a moment as we shift to a little bit more of a societal view, what do you look for in deciding which Knesset party to vote for? And to some people who have American side to them get all flustered, I’m not asking which party you vote for unless you want to say, but just what you look for, what are the things that you consider?

Sruli Fruchter: At this moment in Israel, just like in many countries in the world, Israel’s polarized. Jonathan Haidt calls polarization a mind virus.

It’s a virus that when it infects your mind, you start imagining society’s divided into two parts, and one is good and the other’s evil. Okay? Now, this happened to Brazil, happened to Argentina, happened to the United States of America, it happened, it’s also happened to Israel. We caught the virus. Okay, so in Israel now there’s two camps.

And they’re and one camp claims that they are the national camp, and the other camp is the liberal democratic camp, and one is Jewish and one okay, and one is Jerusalem and one is Tel Aviv. Like we have to remember there’s two camps. Now here’s, here’s a more important question. You ask an Israeli or a political leader, what’s the greatest threat to the future of Israel? Some would say the other side.

Like if I’m in the left, it’s the right. The right, the left. The people on the other side of this fight. That’s the greatest threat to the future of Israel.

And some Israelis would answer you, you know what the greatest threat to the future of Israel is? The fight itself.

Micah Goodman: Hm.

Sruli Fruchter: I think we should only vote for parties that think that the fight is more dangerous than the people on the other side of this fight.

Micah Goodman: Mmm.

Sruli Fruchter: And which has a big nafka mina.

Micah Goodman: Mmm. How do you say nafka mina?

Sruli Fruchter: A practical difference. This has a big, this is this has a major practical practical implication.

Because if you think that the greatest threat to Israel is the people on the other side of this fight, like if I’m a right winger, the people on the left, they are the greatest threat to the future of Israel. If that’s my calculation, that’s my how I calculate risk. So all I have to do is I have to break them, I have to destroy them to save Israel. There’s only one problem.

The people on the other side are thinking exactly the same thing about me while I’m thinking that. So while we’re both trying to save Israel, we’re destroying it.

Micah Goodman: Hm.

Sruli Fruchter: What happens if in my calculation the greatest risk is not the people on the other side of this fight, but the fight itself?

Micah Goodman: Mmm.

Sruli Fruchter: So now my goal is not to destroy them, but to find a way to compromise with them. And the parties that are going to, I believe are going to win the next elections, are the people who are going to call for compromise.

Micah Goodman: Do you think so?

Sruli Fruchter: Yes.

Micah Goodman: But isn’t Bibi leading in the polls? Meaning unless you think that Likud the Likud Party is embodying that and and

Sruli Fruchter: Now, I think Bibi has a very big decision to make now.

Till now, Bibi was leading, his voice was, vote for me, because I could destroy the elites, the deep state, the whatever, the left, the whatever. I’ll just, I’ll save Israel from the left. And some people on the left saying, we’ll save Israel from Bibi, okay. Is Bibi after this victory over Iran, and now Bibi that wants to leverage the victory over Iran to do to Iran what Iran did to Israel? Iran did to Israel, build an axis of proxies to isolate Israel.

The Abraham Accords about building an axis of countries to isolate Iran, and that completes the v’nafoch hu. To do to Iran exactly what Iran did to Israel. And there’ll be complete victory. And for that he needs new coalitions.

Because the far right can’t, I don’t think he could go with a far right to that kind of an idea.

Micah Goodman: But do you think, but I mean are you saying that Bibi is against the, or that that I’m saying on Bibi meaning because he’s against the the fight itself.

Sruli Fruchter: I’m saying many people on the right voted for Bibi because they believed that that the greatest threats are the people that are protesting against Bibi. But I do think it’s possible that Bibi will change.

I hope he’ll change. I don’t know. That’s why the the Bibi question is always a trick question. So, because how do you read Bibi and where is Bibi going?

Micah Goodman: Mmm.

Sruli Fruchter: But I do think that if Bibi will run on a platform, vote for me, I’ll destroy the other side, he’ll lose the elections. I also think anybody on the other side that will say, vote for me, we’ll really get Bibi this time, they’ll lose the elections.

Micah Goodman: But isn’t that kind of what he’s doing with how he’s treated his trial and how he’s

Sruli Fruchter: I think that’s exactly how he’s been conducting himself till now.

Micah Goodman: But then why why would he still be leading in the polls if that’s what Israelis are after? If I mean if Israelis are after somebody to unite.

Sruli Fruchter: I don’t, I don’t, I don’t think he’s leading in the polls.

Micah Goodman: You don’t think so? I thought that recent numbers were saying, especially after Iran that he was

Sruli Fruchter: Yes, but he’s still not, I think he’s not leading in the polls.

Micah Goodman: Do you know who is leading?

Sruli Fruchter: Naftali.

Micah Goodman: Oh, interesting.

Sruli Fruchter: I think Naftali is still leading in the polls. I guess it’s kind of close, but just imagine what Bibi will happen if Bibi becomes a, if Bibi uses his talent not to divide Israel but to unite Israel, he’ll win the elections. Because then all the will win the elections. So it’s just, so right now it’s in Bibi’s political interest to become, I’m not saying he’ll become a uniter.

Micah Goodman: Yeah, yeah, yeah, I understand.

Sruli Fruchter: Maybe things are bigger than him. Maybe habit is bigger than him.

Micah Goodman: But but but if he does, you’re saying that that will expedite his success.

Sruli Fruchter: Yes, and if he won’t, I think somebody else will take over. I think, I think the next elections will be won, Israelis are yearning for unity.

Micah Goodman: Mmm.

Sruli Fruchter: Which means that Israel might be able to be a country that changes the laws of physics.

The laws of physics I mean, ever since, I mean, in polarized societies, the dividers always win. Can Israel be the first post-polarized society? The first society that managed to to to to come out like we thought we, it wasn’t true. We thought we came out of COVID first. It wasn’t.

But this plague of polarization, can we be the first country out of it? Can we leverage this moment in history? I’m not saying we will, I’m saying we can.

Micah Goodman: Which is more important for Israel, Judaism or democracy?

Sruli Fruchter: If you ask, how did Israel defeat Iran now? I mean, not defeat, I mean that great success we had in the past 12 years. It’s a combination of two things.

Micah Goodman: Mmm.

Sruli Fruchter: It’s actually three things. Innovation, right, technological innovation.

Micah Goodman: Mmm.

Sruli Fruchter: Right, this this is the answer to your question.

Micah Goodman: Yeah, yeah.

Sruli Fruchter: Okay. Innovation, creativity, radical creativity, right? And courage, radical courage. Now you ask, where does innovation come from? innovation comes from being a liberal society, where people could think freely.

That’s how you become the startup nation, an innovative society. Where does creativity comes from? From individualism, from not trying to conform to the party line. These are democratic values. Where does courage come from? Where does resilience come from? That comes from being Jewish.

That comes being connected to a tradition, to a story that’s bigger than yourself and you’re willing to sacrifice yourself for something bigger than yourself. Israel’s been successful in this war because it’s hybrid, because it’s a Jewish democracy. That’s what hit Iran in the face. That’s what hit the proxies in their face.

Our innovation, creativity, courage, resilience, courage and resilience comes from being Jewish, comes from being connected to a collective. Innovation, creativity comes from individualism. Israel is we’re hybrids, collectivist, individualist, liberal and national, Jewish democracy. And that’s why I believe the yin and yang as a symbol, where the whole is not where the yin defeats the yang or yang defeats the yin, but it’s the combination of yin and yang, that’s Israel.

Jewish democracy.

Micah Goodman: What role should the Israeli government have in religious matters?

Sruli Fruchter: I think it’s, well, it’s I think it’s best for religion that the government has a minimum role. There is the famous Alexis de Tocqueville where he goes to in the 19th century, French observer goes to America and he realizes that Americans are so religious. They love God.

They have so much piety, they’re so religious. And he realized how is they’re so religious and they’re so, it’s so important for them to keep separation between church and state. And he comes with a conclusion that Americans are so religious, not although there’s separation of church from state, but because there’s separation from church from state. And his theory is the following.

People have a natural healthy suspicion and sometimes even aggression towards political power. That’s healthy. Where power is concentrated, we’re suspicious and sometimes we’re aggressive. Like like, stay out of my life.

That’s healthy. But when religion is married to political power, so the aggression we have towards politics spills over to religion. And the suspicion we have over of regarding politics spills over to religion. That was de Tocqueville’s theory.

Israel proves it’s a reality. When religion uses the power of politics to promote itself, so the suspicion towards politics turns into suspicion against religion. So I think, yeah, I’m not saying Judaism is not the is not the Protestant religion, so it’s not a good analogy. So we can’t separate synagogue from state, but we definitely have to create a larger distance between synagogue and state, not only for the benefit of the state, but for the benefit of Judaism, of Yiddishkeit, of the synagogue.

If we want to promote Judaism, we have to we have to it’s it’s not through legislation, but through conversation, through, you know, without using political power. That’s the way Israelis, many many Israelis, have a very instinctive draw to to to Jewish tradition. Most Israelis want to have an intimate connection with their past and their tradition. They don’t want to be controlled by tradition, they want to be connected to tradition.

Most Israelis are not going to be Orthodox, frum, religious Jews, but they’re going to be something else. They’re going to be something like if you see like the Mizrachim Masortim, like you’re connected to tradition, not you’re not obeying tradition. It’s a different, it’s a different body language. And that’s where most Israelis could be going.

But when they have an allergic reaction to politics and politics is connected to religion, that is blocking the natural tendency of Israelis to be more traditional.

Micah Goodman: Should Israel treat its Jewish and non-Jewish citizens the same?

Sruli Fruchter: Of course. Of course. I mean, as individuals, completely.

Israel is, it’s the national home for one nation, right? For the Jewish people. But it’s the democratic home for every individual that’s its citizens. You see this distinction? As individuals we’re all equal, but as a collective it’s the nation state of only one collective. So the Tikva says nefesh Yehudi homiya.

Which means the national anthem does not represent every Israeli. But when it comes to rights, every we have to we have to have equal rights, of course.

Micah Goodman: Now that Israel already exists, what’s the purpose of Zionism?

Sruli Fruchter: If Zionism is a project to create a state, the state is established, Zionism is over. That’s that’s if that’s the question what is Zionism.

Herzl had two different visions for Zionism. One was creating, one he wrote in 1896 in a book called Judenstaat, The State of the Jews. Creating a state, that’s what it is. And the second he wrote in 1902 called Altneuland.

Now, very very briefly, these are two different Zionisms. And he wrote and both came from the mind of one person of Theodor Herzl. The first Zionism of 1896 is like this. The world is a hostile place for Jews.

It’s a scary place for Jews. We need a Jewish state in order to, because of anti-Semitism. 1902 in Altneuland, he says, the world has problems, has serious problems. That’s why the Jews have to create a state in order to innovate and experiment in different ideas of government and and technology and in order to come up with solutions for the problems of the world.

So the version number one, the world is dangerous, we have to escape the world. Version number two, the world has problems, we have to heal the world. I would say Zionism number one is stage one of Zionism. And stage one of Zionism will end when Israelis will feel safe in Israel.

Maybe this world, this war that maybe, maybe, we don’t know yet. Maybe this war will be seen one day as the war that made Israelis feel really safe in Israel. If this is leads to peace in the Middle East and Abraham Accords expanding and that existential threat created by Iran is dismantled and no new threat comes in, so maybe we’ll be moving from the from the Zionism of Medinat HaYehudim, of the State of the Jews, of Herzl, to the Zionism of Altneuland. A Zionism that doesn’t ask how do we protect Jews from a crazy hostile anti-Semitic world, but a Zionism that asks how do we elevate our how do we use our innovation in order to help, in order to heal the world? That might be a real shift.

That mean we might be able to be witnessing in our lifetime.

Micah Goodman: But wouldn’t you say that Israel is quite far from that second goal?

Sruli Fruchter: Well, I think we are so obsessed with survival. I’ll I’ll give you even worth more. The reason why Bibi keeps winning is because Bibi, because Bibi really, really captures that anxiety.

The Jewish people are under threat, Israel is under threat. We have to be tough, we have to trust no one, and we. And I would say, if it’s true that if this war and the peace that comes after this war, you know, something regional, a regional alliance is created after this war, brings down that existential anxiety, this will also probably be the end of the Netanyahu period. The end of the Netanyahu period also is also the end of stage one of Zionism.

The Zionism of survival. And then a new conversation begins, a Zionism of of inspiration. It’s a new conversation, it’s a different type of leadership, it’s different. So I don’t know if are we in that tectonic shift as we’re talking? It’s hard, you know, Chazal, when they ask the rabbis, when they ask after the Chanukah miracle, they ask, are we going to turn this into a chag? Into a holiday, into Chanukah.

And Rav Soloveitchik observes that the they answer says, the Chazal say, let’s decide next year. Let’s wait a year.

Micah Goodman: For a bit of perspective.

Sruli Fruchter: So everything I’m talking about, I I notice is it’s we need perspective to know if this stuff is right.

Micah Goodman: Yeah, so kind of like you said in the beginning, like you kind of, it’s hard to speak about history when you’re in history.

Sruli Fruchter: When you’re in history. So these are all speculative, but it’s possible we’re in a tectonic moment, a real, where where things are really changing and moving from one, from the first stage of Zionism to the second stage of Zionism.

Micah Goodman: Is opposing Zionism inherently anti-Semitic?

Sruli Fruchter: No.

No, you could be, no, but it could be.

Micah Goodman: It could be. Do you feel like people understand the distinction well?

Sruli Fruchter: Here’s an attempt to oppose Zionism that’s not anti-Semitic. If you say, the idea of nation state is a bad idea, it always brings the nationalism brings the worst out of human beings.

Some people think that nationalism is always leads to xenophobia, always to fascism. Nation states are a bad idea, Zionism is a the idea that the Jews deserve a nation state. I’m against nation states, so I’m against Zionism. That’s not anti-Semitic.

But if you say that every nation has the right for self-determination. Every nation deserves a state. The Jews don’t. That’s anti-Semitism.

Because if I say, let’s say an individual right, like the right to to vote. Okay, if I say, everybody has the right to vote as individuals. The Jews don’t. That’s anti-Semitism, right? So if you discriminate against Jews on an individual level, it’s it’s anti-Semitism.

If you discriminate against Jews on a collective level, that’s also anti-Semitism.

Micah Goodman: How how would you fit your model into a student at Columbia who isn’t concerned, who may not be concerned with nation states in general, but is is looking at Zionism and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and is defining Zionism by its history as they understand it.

Sruli Fruchter: Meaning if they say, okay, Zionism history is Zionism, so I would just say, I’d like to have a conversation with them or her about history. Right? Now, do they know their history? Do they know that the Palestinians were offered an independent state for themselves in 1937? And they rejected it.

In 1947, and they rejected it. And the Palestinians are are stateless today not because of Israeli aggression, because of Palestinian refusal. Do they know that? Like I would just go into history with them. Okay, I’d just have a conversation, do they know this? Cool.

Is the IDF the world’s most moral army?

Micah Goodman: I’m not crazy about that claim.

Sruli Fruchter: Do you think it’s true?

Micah Goodman: I don’t know.

Sruli Fruchter: Why don’t you like the claim? Haas is probably coming after you after this interview.

Micah Goodman: Because I mean I know there’s research that shows that maybe the IDF makes more effort to avoid civilians.

I mean, I don’t know the data. I know there’s some research that supports that. But I’m not, I don’t like the claim so much. It’s it’s about morality at its best.

It’s always about managing a conflict between values. There I’ll I’ll give you an example. In Ruach Tzahal. Ruach Tzahal is the IDF’s

Sruli Fruchter: The code of ethics? Or the

Micah Goodman: Ethic, yeah, our code of ethics.

So you have one value called Chayei Adam, which means if you’re a commander, you are morally obligated to do everything you can to protect your soldiers. Okay? If if you put them under threat for no good reason, that’s unethical. There’s another value there called Tohar HaNeshek, which is implications, you have to do everything you can in order to minimize the damage for civilians or people who don’t threaten you. Okay.

So now, you’re in Gaza, and somebody is aiming an RPG missile at you from a hospital. If you start shooting towards that hospital, you’re violating Tohar HaNeshek. Civilians will die. If you don’t, you’re violating Chayei Adam.

Your soldiers will be under threat. So what’s the right thing to do? It’s you have to sacrifice a moral value in order to implement a moral value. That’s the situation. So what is the most moral country? Like, how do you calculate morality? It’s so complicated.

So my take on the Israeli army is because I have many, many conversations and lectures in the Israeli military, how do you balance values? How do you think about this? To be ethical, it’s not only about being a good person, it’s about being a professional commander. And the more professional we are, the more successful we are in the battlefield and the more moral we are. And in moments of fatigue, and by this war is going on for a long time, you’re less professional in the battlefield, you’re also less professional moral. So it’s a constant, constant ongoing, you have to be very alert moral.

It’s very tough, it’s very hard. And I know that I could say the following, that our commanders are doing their, our commanders are doing the best. And is every soldier always at his best ethical behavior? After a year of 10 months of war and after all this fatigue kicking in, I’m sure it’s much more complicated now.

Sruli Fruchter: If you were making the case for Israel, where would you begin?

Micah Goodman: We have to redefine what makes Israel unique, special, and what Zionists used to call a light unto the nations.

And it used to be that it was socialism. For Ben-Gurion and Berl Katznelson and the idea that we will create, we will teach the world how to really do socialism, not like Lenin, not like Stalin, how to really do socialism. Not top down but bottom up, the kibbutz, not using power, but like and in the 50s and the 60s, people came from all over the world to visit the kibbutz, to visit, to volunteer in kibbutzim, to see the Israeli brand of socialism. Then we’ve changed a bit.

We’ve changed throughout time. In the 90s and 21st century, people will come all over the world to see the startup nation. A different model of what it means to light into the nations. Innovation, individual, people came from all over the world to visit Mobileye, to visit not the miracle of socialism, the kibbutz, but the miracle of Israeli capitalism.

I think we should think about it differently now. In the 20th century, collectivist societies failed. Mao in China and Stalin in Russia, I mean collectivist, Cambodia, collectivist experiments failed. And that led in the towards the end of the 20th century to different people saying, “Wow, collectivism failed, individualism, American liberalism, capitalism, that’s the idea that won and history is over and we know who lost and who won.” That’s Francis Fukuyama’s famous…

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah, the end of history.

Micah Goodman: The end of history, history. I think what we’re seeing now in America and in the Western civilization, we’re seeing, if in the 20th century we saw the failure of collectivism, now we’re seeing the failure of individualism. That leads to loneliness, to lack of meaning, which increases polarization.

You want to belong to a tribe. That’s Rabbi Jonathan Sacks political tribes, but put them, the glue of political tribes of the glue of regular communities is love. If you belong belong to a community that ride bikes together, okay, so that’s love for bike, for bike riding. If you go to shul, it’s for love of Kiddush.

Or ritual. If it’s whatever it is, communities, what unites the glue of community is love. The glue of political tribes is hate. And people that feel so lonely are looking for community and that only increases the mind virus of polarization.

Sruli Fruchter: Mhm. The failure we’re seeing all over, we’re seeing the failure of individualism. I think what you see in Israel is the following. Israel is a hybrid society.

We are hyper-individualists. You have to speak to only two, three Israelis to understand that you’re talking to people that don’t want to be told what to do. David Ben-Gurion said once the worst job in the world is to be the Prime Minister of Israelis. This is in the ’50s.

Because you’re the Prime Minister of 1 million prime ministers. Israelis are hyper, the whole startup nation book is about hyper-individualism. And then, everything’s October 7th, you see these same people building startups startups in Herzliya, you see them in Khan Younis. 150 days in Khan Younis.

That’s collectivism. If individualism is about self-fulfillment, collectivism is about self-sacrifice. And Israelis can move from from one emotional mode of of self-fulfillment to self-sacrifice. Oh, and then miluim is over, so you go back to be’ratzo v’ashov, so easily.

Micah Goodman: The back and forth.

Sruli Fruchter: Back and forth. So Israelis have this, Israelis are hybrid emotionally, not all Israelis. I’m talking about mainstream Israelis.

Not all Israelis. And also ideologically, the Jewish democracy. Judaism is about collectivism. You’re part of a collective.

Democracy have individual rights. So the hybrid formula of Israel, Jewish democracy, is played out by so many Israelis which are collectivists, individualists. So I do think Israel has an important thing to to show the world. After the failure of collectivism in the 20th century and the failure of individualism in the first quarter of the 21st century.

It’s not about the kibbutz anymore, which is collectivism. It’s not about the startup nation, which is individualism. It’s about the holistic version of Israel, the yin yang of Israel. That’s not the case for Israel, that’s who Israel is.

And and I think Israel has something, people in America, Jews in the world, which are living in hyper-individual individualistic societies are always told, or it’s always seems like there’s a tradeoff. For all my liberties that individualism offers me, there’s a tradeoff. The tradeoff is that I have nothing to belong to. Nothing, I’m not in service of anything.

And where there’s no belonging, there’s a weakened sense of meaning. And I’m always using that tradeoff. Okay, so you want belonging and meaning, there’s less rights, less liberalism. It’s like there’s a tradeoff.

Israel is living evidence there’s no tradeoff.

Micah Goodman: Mhm.

Sruli Fruchter: That you could be liberal and national at the same time. That you could be hyper-individualistic and in service of your country at the same time.

Micah Goodman: Mhm.

Sruli Fruchter: That’s what Israel is. And I think in this war, we’re starting to realize that’s not only what we what we are, it’s also a superpower. Because the individualism creates the technology and the innovation and the ideas.

And it’s the collectivism, it’s belonging to something bigger than yourself that creates the courage, the resilience. And we need both to defeat, we need both, we need both to defeat the red.

Micah Goodman: Mhm.

Sruli Fruchter: So we’re realizing it’s our superpower being hybrid.

And I think that’s Israel, that’s I think when you think about the next generation of Zionism, the Zionism of inspiration, not of survival, I think that’s where it is. It’s being it’s cultivating the both pieces and showing that there’s not a tradeoff between them.

Micah Goodman: Mhm. Can questioning the actions of Israel’s government and army, even in the context of this war, can that be considered a valid form of love and patriotism?

Sruli Fruchter: Of course.

Of course.

Micah Goodman: Mhm.

Sruli Fruchter: You want Israel to be the best version of itself and you feel that it’s not the best version of itself. Of course.

There was Rabbi David Hartman, alav hashalom. He said something, he said, when you criticize Israel, he says, I want you to criticize me like my mother does, not like my mother-in-law does.

Micah Goodman: That’s a good one. That’s a good one.

Sruli Fruchter: No, I love my mother-in-law. That’s nothing, but but but there’s…

Micah Goodman: You got to cover your own ground.

Sruli Fruchter: But the idea of when you criticize someone because you hate them, it means you, it’s because you hate them, you criticize, because you see the worst in them.

But because you see the best in them, you criticize them. Because yes, so of course, criticize me, Israeli government. Israelis do that all the time.

Micah Goodman: Do you think there’s enough criticism of Israel from within Israel?

Sruli Fruchter: Within Israel? Of course.

Micah Goodman: So what do you think is the most legitimate criticism leveled against Israel? Not necessarily whether from within or from without?

Sruli Fruchter: Everything is legitimate. Everything is legitimate. So I’ll just go, I’ll say what’s not. So so so because anything else is.

Israel has the right to exist. Criticizing Israel’s right to exist is probably anti-Semitic unless you have a a real abstract explanation, it’s probably anti-Semitic. If you’re saying that Israel doesn’t have the right to protect itself, I think that’s almost like saying it doesn’t have the right to exist.

Micah Goodman: Mhm.

Sruli Fruchter: So as long as you believe, if as long as our our assumption is, Israel has the right to exist and therefore the right to protect itself, because in this neighborhood if you can’t really protect yourself, you can’t really exist. Besides that, now we can argue how we protect ourselves.

Micah Goodman: So are criticisms of apartheid or genocide legitimate in your eyes?

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah, no, no. Saying apartheid, genocide, that’s saying that Israel does not have the right to exist.

Micah Goodman: Why?

Sruli Fruchter: Because the whole purpose of saying that Israel’s very presence here is a crime. crime. Well, is that what they’re saying? Meaning, are the people who who allege, meaning the reason I bring such extreme examples is because you had set everything aside from saying

Micah Goodman: Okay.

Sruli Fruchter: criticism of Israel is permitted except

Micah Goodman: So I can’t, I don’t know, because I I feel like saying, okay, saying that that’s

Sruli Fruchter: I think it’s easier to do the question originally, which is like

Micah Goodman: No, no, I I think that’s saying that Israel can’t protect itself.

Sruli Fruchter: Why is that?

Micah Goodman: Because okay, because if they protect myself, because the tragedy that Hamas designed, building an army of terrorists, hiding beneath civilians, means that my only way to protect myself is entering this tragedy.

Sruli Fruchter: But that’s not what people, that’s not what all people are saying, meaning there are there are people and there are organizations that have shifted over the course of the war. And I’m not saying that their claims are legitimate, but meaning from the people

Micah Goodman: saying genocide.

Sruli Fruchter: Because there were people from from day one who who said Israel’s committing genocide on October 8th.

I totally hear what you’re saying. But from what you were saying, the people who have said, let’s say pretend, let’s say on September 24th

Micah Goodman: I I just have one question. Okay. I assume the word genocide doesn’t it comes from the numbers.

It comes from the numbers of Palestinians that have died.

Sruli Fruchter: Not necessarily. Meaning there have been people who’ve said it’s because of intention or it’s because of statements made. Meaning, but all this is this is not me defending, this is not me defending the genocide claim.

Micah Goodman: But because genocide doesn’t mean, I mean, if you’re saying an act of a certain soldier in a certain place of Gaza was immoral, I could say that also.

Sruli Fruchter: Of course. No, no, but they’re saying that on a systemic level

Micah Goodman: on a systemic level.

Sruli Fruchter: statements from Israeli ministers, based on statements from Netanyahu, based on policies taken.

Micah Goodman: If you’re saying that there is a policy by Israel to target and kill Palestinians, first of all, it’s just it’s just not true, it’s just wrong. But if you dig deeper, you realize, okay, Israel realized that the price of destroying Hamas was that civilians will die, and we were willing to pay that moral price in order to fulfill another moral obligation of protecting our lives. And it was a very complicated

Sruli Fruchter: But isn’t that what they would dispute? Meaning they would dispute whether or not these actions were a) legitimate or b) necessary for Israel to exist.

Micah Goodman: Okay, so so if you’re saying it was possible to destroy, if you if you’re saying we can’t destroy Hamas, that’s saying that Israel does not have the right to protect itself.

If you’re saying there is a different way to destroy Hamas, while Hamas is hiding beneath population, so I would like so offer the alternative and then we could and then we could measure it. I never heard somebody said this, “Oh, you could just destroy Hamas in a sterile

Sruli Fruchter: No, but I mean people people’s arguments have been that that wanting to destroy Hamas is an impossibility. Meaning they say that it’s impossible to destroy Hamas because a) it’s an it’s a terrorist organization that’s essentially an ideology where for every 10 people you kill, you’ve now like 100 are are going to be born from

Micah Goodman: But destroying Hamas means three things. It means okay, it just

Sruli Fruchter: I’m not looking to get so I don’t want to get lost so much in because that this in itself could be a podcast episode to discuss, you know, the the merits of the meaning of destroying Hamas.

Micah Goodman: Yeah, well I I

Sruli Fruchter: I guess I I mean just to just to go back to my original question, I’m just curious.

Micah Goodman: You know what, you know what? Maybe maybe it’s legitimate, but it’s stupid.

Sruli Fruchter: Mmm. So, but are there is there a claim that people make against Israel that many people may dismiss that you’re like, actually there is some legitimacy to that? I’m not saying the genocide claim.

You may say it’s legitimate, but it’s stupid. But is there a claim that people make towards Israel that some people are more apt to dismiss, that you say, you know what, I hear that claim and I think there’s legitimacy there.

Micah Goodman: Well, as I told you, I think regarding the I think we made mistakes regarding the hostages in certain points. I do think that our military, it’s hard to be judgmental about our military because if I was in military now for a year and 10 months, I think a lot of things you see, there’s the component of fatigue, which is very hard, it’s very hard for people outside the army to see how hard it is to fight a war for a year and 10 months on many many levels and on many many layers.

But did our army intend to kill Palestinians? Absolutely not. Do we have do we make mistakes? Yes. Do we have individual soldiers that made more than mistakes but but misbehaved? Yeah, I’m I’m I’m sure we did. I’m sure that happened.

Sruli Fruchter: What do you think the world misunderstands about Israelis?

Micah Goodman: Hm. Here’s something interesting about Israelis. How not militant they are. Mmm.

It’s very interesting. Usually when you see people that were in the military for a long time, they’re very militant. They’re like, you know, there there’s something militant about them. Which is fine, I’m not judgmental.

But you see Israelis that spent a year that were in Gaza and Lebanon and then they get together, they’re not militant. They’re soft. They sing. They pull out their guitar.

They’re vulnerable. They’re very vulnerable. This generation of Israelis is the toughest generation of Israelis ever, shockingly tough, and so vulnerable, and so open, and they could speak about their emotions. It’s just something so…

And that’s something I think many people don’t know about Israelis. If you you assume these people that did what they did in Iran, Lebanon, Gaza, they’re probably these macho… No, they’re not. They’re very balanced.

They’re very interesting. They’re very they’re not only masculine, they’re also feminine. There’s something interesting there. It’s a yin yang.

Sruli Fruchter: Do you think peace between Israelis and Palestinians will happen within your lifetime? No. Why?

Micah Goodman: I don’t know how long I’m going to live for, but a lifetime. I I want to change my answer. In the foreseeable future, no.

Why? Because I think it’s too much to ask for Palestinians. I don’t blame the Palestinians. It’s too much to ask from them. Asking the Palestinians to recognize the existence of a Jewish state in this land is actually asking them two different things.

It’s asking them to give up on what they believe is their religion. More than 50% of Palestinians believe in the following interpretation of interpretation of Islam, that this land that was that is waqf, it used to be, it used to be owned and used to be Muslim under Muslim sovereignty. And therefore it’s waqf, it’s sacred land. And therefore, it’s illegitimate for a a sovereign that’s not Muslim to govern this land.

Now Yusuf al-Qaradawi, one of the greatest poskim, like a great Sharia legislator, said that the only land in the world that that statement is valid is Israel. Is Palestine, what he calls Palestine. The Muslims used to also control Spain. He says, no, we should, any foreign control over this land is a violation of Sharia.

So if Palestinians say we recognize Israeli sovereignty, that’s turning their backs on the Sharia, on the halakha, the way most of them see it. That’s one. Two, peace means they give up right of return or effective right of return, Haq il-Awda. And the way they count, between five to seven million Palestinians used to live here and now they don’t live here anymore.

They have to come home. And they were like, no, if peace means you’re giving up on that, because that means we don’t have a state, a state of our own. So we’re asking them to do two things for peace. We’re asking them to give up on their solidarity and in their on their theology.

To give up their, to turn their backs on 5 million refugees and to turn their backs on Sharia. Which means we’re actually asking them, in order to achieve a statehood, liberty, political liberty, we’re asking them to give up on their identity. Now, most Israelis don’t see that. Most Jews don’t see that.

That the two-state solution we’re asking them is you sacrifice your identity, Muslim identity, Palestinian identity, and you’ll get liberty. That’s too much to ask for them. We shouldn’t do that. We should think about, we should bring the stakes down, not ending the conflict, but speak about maybe short-term agreements.

A hudna of 40 years. Speak about and we violated here and there. It will be this conflict that’s going to stay alive. I think it’s possible to bring it down, to bring the temperature down.

But any attempt to solve the conflict always amplifies that same conflict. That’s the that’s the law of history ever since 1937.

Sruli Fruchter: What should happen with Gaza and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict after the war?

Micah Goodman: What should happen in Gaza?

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah.

Micah Goodman: There’s many possibilities.

I’ll tell you what I think, I mean, from an Israeli perspective.

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah, well, from your perspective.

Micah Goodman: From my from our perspective, we need two things. One, not to be there.

I don’t want our soldiers, I don’t want Aza to be our Vietnam. I don’t want our soldiers to be patrolling Gaza and governing Palestinian population in Gaza, we don’t want that. On the other hand, we can’t let Hamas be built up. Which means what we need is we don’t want Israeli presence, we want Israeli access.

Access means we have intel of a Palestinian planning an attack in Shajaiya, we’re going to, we’ll go into Shajaiya. Either by air, by drone, or special units. Which means we need access, not presence. Now, what’s the arrangement that will give us access without presence? What’s the arrangement that will do that? There’s many ways to think about that.

But that’s what’s right for us. But here’s a point that has to be made. For the Palestinians, as long as Hamas is is in Gaza, Gaza will never be rebuilt. And here’s why.

To be rebuilt, you have to have foreign investments, like Saudi foreign investments. If you’re in charge of the the foundation of that the they take their oil money and they make foreign investments, right? They’re going to make investments now in the US for for your president. And the American by the way?

Sruli Fruchter: American Israeli.

Micah Goodman: Can I be friendly with an American just for the story?

Sruli Fruchter: Go for it.

I’ll take, I’ll take the straight bullet.

Micah Goodman: Okay. Now, um,

Sruli Fruchter: Are you American?

Micah Goodman: Yeah.

Sruli Fruchter: Kol nas tembel, ana nas tembel.

Micah Goodman: Kol nas tembel. Yeah. And I was born and raised here, but yeah, I might be an American citizen. So if Hamas is there, so you know with not low probability that Hamas will direct one day its missile at Israel.

And what will Israel do? It will bomb Gaza. Which means all your investment goes down the drain. Which means the risk is so high if if Hamas is there, no one will make that investment. So there’s no real future for Palestinians if Hamas is there.

Israel, by the way, has a future if Hamas is there.

Sruli Fruchter: As long as we have access, we can mow the lawn. That’s what people in the world don’t understand. If you want the best for Palestine, Israel could find an arrangement, it will be protected from Gaza.

At this situation now, we could find an arrangement that we could protect it from Gaza without presence but with access. But for the Palestinians, we need Hamas eradicated. Or else the Palestinians have no future.

Micah Goodman: I was actually going to ask on the first thing you were speaking about, are you scared about the support growing in Israel to build settlements in Gaza? Even in the government, that of those who support it.

Sruli Fruchter: Yeah, I don’t think it’s going to happen. I don’t think it’s…

Micah Goodman: Why?

Sruli Fruchter: Because it’s only a… there was only a minority of Israelis that want it.

The prime minister doesn’t want it. The majority of Israelis don’t want it.

Micah Goodman: But for the… so I am curious, for the Israelis who say, we pulled out of Gaza in 2005, we uprooted Jewish homes and Jewish settlements and look what we got 20 years later.

Maybe resettling is the answer. How do you respond to that?

Sruli Fruchter: The reason why Gaza is the way it is is not because of the disengagement, but because of Oslo. In the Oslo Accords in the ’90s, Israel left the villages and the Palestinian towns and told them, okay, now you can build your own autonomy on your own. And what happened was, both in Judea and Samaria, the West Bank, and in Gaza, they started arming themselves and arming themselves.

And all that exploded on Israel in the second intifada. And then as a result, the second intifada, when Arik Sharon came into power, I’m talking now 2002, I think it was March 2002, we went into the operation called Chomat Magen.

Micah Goodman: Okay.

Sruli Fruchter: Defensive Shield.

Defensive Shield. Which means, but we did it only in Judea and Samaria. Our brigades into Tulkarem, in Jenin, and Ramallah, and Beit Lechem. We entered all, we entered towns, and we dismantled the terrorist infrastructure in these towns back in 2002, 2003.

And by the way, the power of unity, it was Shimon Peres was the foreign minister, Arik Sharon was the prime minister and really, when the icon of the right and the left unite, there’s a lot we can do. In Israel’s history, by the way, wars by national unity governments like the Six-Day War were successful. So we go into, so we do Chomat Magen, but we didn’t do that in Gaza. We didn’t do that back then in Gaza.

And what happened as a result of Chomat Magen, not only did we dismantle the infrastructure of terrorism, we also somehow created the legitimacy to go back in whenever we wanted. We have Intel, we go in, we take out the terrorists. And to do what Israelis call, lekaseach et hadeshe.

Micah Goodman: Mowing the lawn.

Sruli Fruchter: Mowing the lawn. So while we dismantled the infrastructure and then mowed the lawn in Judea and Samaria, we didn’t do that in Gaza. So the lawn just grew and grew and grew. And you know what this war is? The Chomat Magen that we didn’t do in Gaza in 2002, we had to do with a much more armed Gaza in 2023.

So, settlements in Gaza is not what creates the missing Intel and the access. It was the… it was, it goes back to Oslo. So if we…

if we come out of this war where on the one hand, we dismantle the infrastructure and now, we’re not… we have access, like we go in and… like like in Lebanon, like in Lebanon with the Hezbollah. When we have Intel, we bomb, right? If we have that, so that would be the answer to our national security problems.

That’s the guarantee that October 7th won’t happen. I don’t really know how settlements in Gaza create security. I mean, there is a story, but tell me how it goes. Let’s be practical about this, how this goes.

Military access in Gaza is what you need, not Jewish presence.

Micah Goodman: I mean, you you want Jewish presence for other reasons.

Sruli Fruchter: For prophetic, biblical, messianic, other narratives, which I I understand them. But for security reasons, you just need access.

Micah Goodman: Where do you identify on Israel’s political and religious spectrum? And do you have any friends on the other side?

Sruli Fruchter: Well, I’m a centrist, but let me just explain what a centrist means. It doesn’t mean that I’m in between the right and the left. It means I internalize chapter three of Ecclesiastes. Chapter three of Ecclesiastes, he speaks about, there’s a time for everything.

There’s a time to speak, there’s a time to be silent. There’s a time for peace, there’s a time for war. There’s a time to hug, there’s a time to stay away, right? And he concludes and he says that hakol asah yafeh b’ito. Everything has its time, everything has its moment.

Now if you channel this politically, I have a problem with ideologues. I think ideology brings down your political IQ. Ideologues have a tendency to think that they have an idea and it’s always right. It’s always right.

If you’re a militant, if you’re a militarist, so using force will solve all your problems. If you’re a pacifist, so talking will solve all your problems. If you’re a capitalist, just privatize, the market will solve your problems. If you’re a socialist, just nationalize and…

And chapter three of Ecclesiastes says something else, says, it’s not that one idea is wrong, the other idea is right. All ideas are right, all ideas are wrong. We have…

Micah Goodman: asks a different question.

It’s not what’s the right idea, ask what’s the right time. And I’m a centrist because I believe that the right has great ideas, the left has great ideas. I I don’t like that ideas are discarded because of their brand. Oh, it’s left, so I’m against it.

Oh, it’s right. So, yeah, political IQ goes down when you disregard an idea just because of its brand, not because of its content. So I think all idea now, so I just want to ask, so I want to be flexible enough to ask what’s the right idea for this time?

Sruli Fruchter: And religiously?

Micah Goodman: I think I shared with you some theological Maimonidean insights in the beginning.

Sruli Fruchter: You did.

Do you have an, do you identify anywhere religiously? Like what’s

Micah Goodman: No.

Sruli Fruchter: And do you have any friends on the quote unquote other side?

Micah Goodman: Well, since I’m a centrist, so I have really, have friends which I learn from, listen to, on both sides.

Sruli Fruchter: Lovely.

Micah Goodman: I I would say if you if you want to really, really, really push me, at this moment,

Sruli Fruchter: I can push you.

I’ll push you, a little bit, I’ll push you.

Micah Goodman: At this moment, I would say I’m leaning more to the right, but not because I’m a right-winger. Being a right-winger turns an idea into an identity. And once ideas become from what you think to who you are, so they blind you from reality.

I want to be, I want my eyes to be liberated from ideas. So I get, I would say now I’m centrist leaning to the right, but it’s not an identity, I’m not a right-winger.

Sruli Fruchter: Because in this moment you see, because in this moment you see I think certain, you think ideas on the right seem to be more…

Micah Goodman: suited for the reality?

Sruli Fruchter: I, yeah, not the far right. Yeah.

Yeah. And for our last question, do you have more hope or fear for Israel and the Jewish people?

Micah Goodman: I have a lot of hope for Israelis. The Jewish people is bigger. I think that Israel might be standing in front of a massive opportunity, while the Jewish world is might be standing in front of a massive crisis.

Sruli Fruchter: Mmm. What’s the opportunity, what’s the crisis?

Micah Goodman: But but another thing, but I think the bigger question is humanity. Because I think the rise of AI and what might lead to AGI, artificial general intelligence, and to superintelligence, it’s so big, so terrifying, and it might happen in the near few years. So I’m terrified regarding humanity and optimistic regarding Israel.

The problem is Israel’s part of humanity. So how do you fit that together?

Sruli Fruchter: Hopefully you can guide them forward. Well, Micha, thank you so much for answering our 18 questions. How was this for you?

Micah Goodman: It was pleasant.

It was nice.

Sruli Fruchter: That was really an excellent interview and conversation in so many different areas and for so many different reasons. I hope that you got as much out of it as I did. And I want to hear your thoughts as we are closing up this series.

18 Questions, 40 Israeli Thinkers. What do you want from us next? What are you hoping for? Thank you as always to our friends Gilad Brownstein and Josh Weinberg for editing the podcast and video, respectively. You can reach us at info@18forty.org for all your questions, comments, criticism, and literature. So until next time, I’m your host Yisroel Fruchter and keep questioning and keep thinking.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Julia Senkfor & Cameron Berg: Does AI Have an Antisemitism Problem?

How can our generation understanding mysticism, philosophy, and suffering in today’s chaotic world?

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

What Garry Shandling’s Jewish Comedy Teaches About Purim

David Bashevkin speaks about the late, great comedian Garry Shalndling in honor of his 10th yahrzeit, which is this Purim.

podcast

Aaron Kotler: Inside the Lakewood Yeshiva

We speak with Rabbi Aaron Kotler about the beginnings of the American yeshiva world.

podcast

Yehuda Geberer: What’s the History of the American Yeshiva World?

We speak with Yehuda Geberer about the history of the yeshiva world.

podcast

Alex Edelman: Taking Comedy Seriously: Purim

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David is joined by comedian Alex Edelman for a special Purim discussion exploring the place of humor and levity in a world that often demands our solemnity.

podcast

Pawel Maciejko: Sabbateanism and the Roots of Secular Judaism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to historian and professor Pawel Maciejko about the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, Sabbateanism, and the roots of Jewish secularism.

podcast

The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism