Hadas Hershkovitz: On Loss: A Husband, Father, Soldier

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Hadas Hershkovitz, whose husband, Yossi, was killed while serving on reserve duty in Gaza in 2023—about the Jewish People’s loss of this beloved spouse, father, high-school principal, and soldier.

Summary

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Hadas Hershkovitz, whose husband, Yossi, was killed while serving on reserve duty in Gaza in 2023—about the Jewish People’s loss of this beloved spouse, father, high-school principal, and soldier.

In the second year of the war, we’re grappling not only with the depth of our losses, but with how to make meaning of them as we continue to live in their aftermath. In this episode, we discuss:

- How has the loss of Hadas’s husband sparked a renewed urgency in her dedication to uplifting the Jewish People?

- How do we confront the anger and blame we may feel toward others in the wake of collective tragedy?

- How can we cultivate the positive thoughts and spiritual clarity needed to uphold our moral responsibilities in difficult times?

Tune in for a heartfelt conversation on what it means to transform Torah into a living song sung by the Jewish People.

Interview begins at 30:30

For more 18Forty:

NEWSLETTER: 18forty.org/join

CALL: (212) 582-1840

EMAIL: info@18forty.org

WEBSITE: 18forty.org

IG: @18forty

X: @18_fortyWhatsApp: join here

Transcripts are lightly edited—please excuse any imperfections.

David Baskevkin: Hi friends and welcome to the 18Forty podcast where each month we explore a different topic balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host David Bashevkin and this month we’re continuing our exploration of loss. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big, juicy Jewish ideas. So be sure to check out 18Forty.org where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails.One of the most powerful passages in Psalms, in the book of Tehillim, is found in the 23rd chapter of Psalms where we read, and this is known both in the Jewish world and outside the Jewish world, because it is something that I think many religions that adopt the New Testament found this verse to just be incredibly powerful.

It’s in the 23rd chapter. It’s read in traditional Jewish communities very often the third meal of Shabbos. And it says as follows, it says, Gam ki eilech b’gei tzalmavet. Even though I walk, literally b’gei tzalmavet, in the, in the shadow of death, lo ira ra, I will not fear evil.

I will not fear harm. I will not fear suffering. Even in that moment, walking in the shadow of death, I will not be afraid. Why not? Ki ata imadi, because you are with me.

Shivt’cha u’mishantecha, your stick, your staff and your rod, hema y’nachamuni, provide me comfort.And it’s a powerful verse because who hasn’t been in some situation, in some point in their lives of some period of brokenness where they looked up and whether or not they believe in God or the traditional God, you look up towards something and say, I need help. And it’s in those moments where there’s some sense of comfort, there’s some sense of relief. There’s some change in perspective from that knowledge that no matter where we are, there is something transcendent with us. Lo ira ra, I will not fear any evil, ki ata imadi, you are with us.

You are with me. And no matter what happens, there is something transcendent that is a part of my story that can never be extinguished, that can never be broken. And then it ends that your stick and your rod are what provide me comfort. Shivt’cha u’mishantecha, that’s the Hebrew, hema y’nachamuni.

Your staff and your rod will serve as my comfort.It’s a powerful verse that has been put to song by so many. And plainly, plainly read what this is talking about is that sense of transcendence that we can hold on to in times of loss, that there is something that we are attached to that is beyond ourselves, that can give us comfort, that will never be fully lost, will never be fully forgotten. In some ways it reminds me of the famous story that Yaffa Eliach cites in her Chasidic Tales from the Holocaust where she quotes this incredible story that is repeated quite often. I return to it quite often of what it represents.

It’s I believe it’s the first story in the book titled Hovering Above the Pit. And it tells the story of the Bluzhover Rebbe, was an incredible person, happens to be, I believe the the son of the Bluzhover Rebbe was a patient of my father and every year growing up, I believe that’s how they were related, but every year growing up the kiddush cup that we would use on Pesach, on Passover, was a gift that the Bluzhover Rebbe gave to my father. He came to my, I remember he came to my sister’s wedding, that was a very big deal. But there’s this incredible story of the Bluzhover Rebbe, this is the Bluzhover Rebbe who was alive during the Holocaust, and he had a friend who was, when you’re, when you’re persecuted by Nazis, your friends extend beyond your traditional Chasidic community.

And he was standing next to this friend and the Nazis barked at both of them and said, we we have to, you have to jump over this pit. And it was this really wide pit and the Bluzhover Rebbe was a very old man. at the time, wasn’t so strong, and there’s no way that he was going to be able to to jump over. So this man who was sitting next to the Bluzhever Rebbe, who was not a Chasid, said, you know, all your efforts, you can try to jump over this pit, it’s not going to work.

And the Rebbe, who was already in his 50s, grabbed the hand of his friend and said, we’re we’re going to jump. We’re going to do it. And on the count of three, they closed their eyes. They sprinted ahead and they just jumped.

And when they opened their eyes, they were standing on the other side. And this Jew who was sitting with the Bluzhever Rebbe was like, incredible. Like, Rebbe, how did you do it? Like, how did we how did we jump so far? How do we do that? And he said, I was able to jump so far ’cause I had something holding me up. I was holding on to the zechus avos, to the merit of my ancestors, to the transcendent identity that I hold within me.

I was holding on to the coattails of my father, and my grandfather, and my great-grandfather of blessed memory. And then the Rebbe looked at him and said, my friend, how did you reach the other side of the pit? And this person who was not a rebbe said, I was holding on to you. And this story for some reason reminds me of that feeling of gam ki eilech b’gei tzalmaves, even though I am walking in the shadow of death, even though I am surrounded by loss, by hatred, by persecution, whatever that situation may be, lo ira ra. We don’t have to be afraid.

Ki ata imadi. We have something to hold on to. We have transcendence. We have eternity.

We have a purpose that both addresses every moment of our lives and yet can elevate every moment of our lives. And so long as we have that transcendence that we hold on to, and sometimes it’s a friend that we have to hold on to, it’s a parent, it’s a child. Very often we have different things that we hold on to that represent that ata imadi, that you, referring to God, literally in addressing God as you, you are with me. That form of tangibility, that form of certainty, that’s when we need to grab on to something.

And that’s a great comfort. That is a great comfort both as a walking stick, something to lean on to. And that’s also a comfort when we’re being hit with a stick, when the stick is is is chasing us, when the stick is our adversary, and not our our walking mate. That both shivtecha u’mishantecha, both of these Hebrew words refer to different types of stick.

One’s a walking stick, but one’s a stick that you usually you hit with. You you could hurt somebody with, but both of them can serve as comfort. Because the comfort that we understand is that even our suffering, even pain, even loss can be elevated. They too can be a part of the ata imadi to appreciate the transcendence and resilience of what being a Jew is about, to appreciate what the Jewish soul can contain is really otherworldly.

And it is an incredible comfort. It is a comfort I know myself, and I think anyone who has felt that they’ve been in that situation of walking in the shadow of death, and that could mean different things for different people, there is a comfort of holding on to the transcendent, of finding strength from the transcendent, of finding a way to frame and infuse meaning even in the darkest of places. And this episode, like so many of our episodes, is not just about loss, but this episode is something that we try to do every year, which is right before Tisha B’Av, which is the commemoration of the destruction of both the first and second temple, the first and second Beis HaMikdash, to have a little bit of time to reflect on the notion of exile, on the notion of loss, without examining maybe more detailed the ritual points of loss that we’ve been discussing, but instead to step back and realize that Tisha B’Av presents a very unique opportunity for the Jewish people, that we are given this gift of a day of reflection, which unfortunately is always wrapped in suffering, but the gift inside is the knowledge that no matter what the suffering or the pain or the angst or the anxiety that we feel, we have an ata imadi, a you are with me, that can elevate and transcend any situation, that can bring, to paraphrase the words of my dear friend, that notion of hope at first sight. Maybe not love at first sight, but hope at first sight.

Hope that can come in a moment, knowing that every moment of our life can be sanctified, can be made holy, even those that are painful, even those that are wrapped in difficulty and suffering.There is another explanation to this verse that I was hesitant to share and I struggled with for many years. It’s a very beautiful explanation. It’s a Chassidic reinterpretation that I heard many years ago from my teacher Rav Moshe Weinberger. It’s not his own explanation.

It’s it’s it’s cited in earlier Chassidic sources. It’s very, very beautiful, but I always had trouble with it. Instead of the plain meaning of the verse, which is that even though I walk in the shadow of death, I am not afraid because you are with me, it’s an inversion a little bit of that meaning. And instead of reading it that way, you punctuate the verse differently, like this Chassidic reinterpretation, which is always able because we don’t have that type of punctuation in the Torah.

It allows itself to be interpreted in so many ways. And instead, the interpretation that is that I heard many, many years ago is Gam ki eilech b’gei tzalmaves, even though I walk in the shadow of death, Lo ira, I’m not going to be afraid. I’m not afraid. This is this world.

We have one life in this world. We know what the purpose is, we know what our marching orders are. Ra. Do you know what’s bad? What’s bad is ki ata imadi, is that you God are with us in exile.

That the notion of divinity is with us in exile. And the first time I heard this, I’ll be perfectly honest, it it bothered me a little bit because how can we dismiss, it felt like, the the suffering of the Jewish people? How can we, you know, say, the bad part is that is that God is with us. No, the bad part is that is that we’re suffering, that we feel that suffering. And it felt to me, and it was certainly not the way it was given over.

I’m not, God forbid, I’m not criticizing Rav Moshe Weinberger, far far far from it. It was just my own struggle in what it really meant. What what is so bad that God is with us? Isn’t that the ultimate comfort? How could we punctuate a verse like this, even a Chassidic reinterpretation to say that even though I walk in the shadow of death, I’m not afraid. But you know what’s bad? You know what’s ra? Ki ata imadi, that you’re with us here.

That you’re also in exile. The divine idea is in exile. And it it kind of it it it bothered me, like, what is that badness that that God, so to speak, is in exile? And I think over the past couple of years, my eyes have really been opened to what this, at least to me in a very personal way, looks like and feels like, and that is the exile of of the divine idea itself. The exile, so to speak, of the notion, of the vision of what God provides.

Part of what exile, part of what suffering, part of what pain ultimately does, is it makes the notion of God much more intimate, much more personal, much more urgent, but it very often can diminish the divine idea. It can diminish the vision and the majesty of the gift of divinity to this world. Where you could imagine like a like a young child who cries out for a parent. And, you know, I have it over here, you know, anytime your children come home with these like, you know, Father’s Day or thank you Dad stuff.

So like like any parent, I love them. I have one hanging in my office. I took it down in front of me right now. But you read it, and you know, I wouldn’t call it the best resume of what I’ve provided my children.

It’s nice, but it doesn’t capture it. It’s it says, I’m looking at one now. It says, my daddy, my daughter wrote this, it’s beautiful, and I love it. It’s very colorful.

It says, my daddy, he buys us candy, he buys us fun toys, my daddy drives us to far away places, he does fun activities with us. Those are all absolutely wonderful and mostly true. I don’t look at that as the as the most accurate summation of of who I am and what I’ve even provided for my own children. There’s something very childlike about, you know, why do I love my parents? They they buy me candy, they get me toys.

We are sometimes diminished as a people when we are in exile and we and and we are suffering. Where you look up and all you can think about, all you can hope for is just the relief of that suffering. If you’ve ever struggled financially or know someone who has struggled financially. It’s like the walls of your universe cave in and become very small where the only way out is I I need this.

I need the money. I need a health recovery. I need I need my enemies to stop chasing after me. And your needs and your wants can become as personal and as intimate and as urgent as they are.

And we’re not diminishing that for even a moment. But ultimately, the urgency and the pain and the suffering produce an idea of hope, an idea for the divine that ultimately is not the grandest vision of what it’s supposed to be. And in a lot of ways I feel like exile has diminished and the suffering that the Jewish people have been through has in many ways diminished our capacity for vision of what Yiddishkeit is supposed to be. It has diminished our own creativity, our own imagination of developing that healing vision of Judaism and the Jewish people and our commitment to God, Torah, and everything that that represents.

The pain and suffering and trauma of exile can diminish it. It can make it much smaller. We just want our problems fixed. I just want, I just want to get through this next week, this tomorrow, this problem that’s right in front of me.

And instead of remaining and holding on to the loftiest ideas of transcendence, to the loftiest ideas of our eternal purpose on this earth, like a child praising their parent for buying them candy, we can diminish the scale, the magnitude, the scope of divinity when the acuteness of our problems are the only frames, the only language that we have with which to articulate the urgency of the divine idea. And that to me is very much the pain that is at the heart of our continued exile. It is in many ways how I understand that Chassidic reading of this verse, Gam ki eilech b’gei tzalmaves, even though I walk in the shadow of death, lo ira, I will not be afraid. Ra, you know what’s evil, you know what’s bad about this? Ki ata imadi.

Is that part of exile is that God, the divine idea is in exile. And that so long as we do not have a vision of Yiddishkeit, of Judaism, of purpose that can encompass the entirety of the Jewish people, we are not yet redeemed. Redemption means a purpose, a vision that can encompass everyone, that actualizes and gives purpose to the present of everyone’s lives. And in exile, whether or not whatever community you’re in, whatever community you’re in, whatever Jewish community you’re in, there is a diminishment.

We think smaller in exile. We think smaller in exile and there is this sense of, we use this word, I don’t like how negatively it sounds, but I think the fact that it sounds negative is also a product of this exile. And that’s, it just feels tribal. This is just tribalism where the same like everybody else.

We don’t, we’re not, we’re detached from a transcendent purpose. And that feeling, I think, is the product of the smallness of exile, of of how urgent, you can’t think about anything else when you’re bleeding. You can’t think about anything else when you’re suffering aside from what’s your own pain. And because of that, that’s where God is too.

Ki ata imadi. You want to know what’s really bad about exile? What’s really bad about exile is that the idea of the divine is also in exile. Our ideas of redemption are in exile. We are not able to think redemptively.

We think narrowly, traumatically, reactively, always worried what how it’s going to affect me, affect my children, take away from me. And it becomes a very adversarial existence. And instead of linking arms, infighting happens in exile, communal competitiveness, communal triumphalism, we’re better, you’re better, I’m better. Instead of the collective commitment to figure this out for all of us, to figure this out for existence and for humanity, to realize that the idea of Yiddishkeit, the idea of God is so much bigger, is so much bigger than any one approach.

approach, than any one life, than any one model. And we very often take that lofty idea, that idea that has infused the world with the capacity to construct meaning, that has infused the world with the ability, with the inherent innate need to find purpose that every human being feels. And we take that loftiness and in our suffering and in our pain and in our own smallness and our own trauma, we bring divinity and we bring religion and we bring religious authority down into that smallness. And I think that’s something that every community, every individual has their own examples in their head of what that represents, and that’s okay because I think that is something that we’re all guilty of.

We’re all guilty of because we don’t know any better. Nobody taught us to think beyond. We all have exilic minds in many ways. And I remember there was a specific point in the war where I heard marching orders.

I heard that sense of vision of what Yiddishkeit can be and should be for ourselves and the world. And it was the words of a commander who was speaking in Hebrew, and it really sent chills up my spine. I want to play the whole thing for you because it has such an effect on me. It’s in Hebrew, so I don’t expect you to understand it, but this is a commander, an IDF commander who was speaking to the troops right as they prepare to enter to fight and destroy Hamas.

And this is what he said.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Plugah aleph, chinah orot u’mifratza shebe’am Yisrael. Lichatzi shanah she’haplugah nilchemet yachad katef el katef, yeminim u’smolanim, dati’im v’chilonim. Anu yachad bachazit u’mishpachoteinu she’hafchu l’mishpacha achat yachad ba’oref.

Namshich u’nekayem et dvarav shel Rabbi Akiva shera’ah b’mot talmidav v’tzivah lanu v’ahavta l’reacha kamocha. Lochamim, ata et milchama. Nasim et hamachlokot batzad v’nitached yachad sviv hamatara hayechida, netzach Yisrael.

Family: Tachanot argentina kan kodkod, acharai l’hatkafa, l’hashmada v’chisul ha’oyev b’rafiah, acharai sof.

David Baskevkin: I’m not sure if you were able to hear that clearly, and even if you were, I’m not sure you’re able to understand the Hebrew. I just want to translate not word for word, but what this commander was saying because it sent chills up my spine and I come back and play it and replay this because it had such an effect on me.

He said they’re about to enter into Gaza and he says, right now there’s no left wing, there’s no right wing. We’ve been fighting shoulder to shoulder for half a year, whether it’s right wing, left wing, religious, not religious. Over here, we’re unified on the battlefield and we’ve become one family and we are unified on this home front. And we’re going to continue and he invokes the words of Rebbi Akiva who said that the most important principle of the Torah is Jewish peoplehood is v’ahavta l’reacha kamocha.

is our connection to one another. We put all disagreements to the side. This is really the most powerful moment in the entire things. Let me just read it in Hebrew and then translate it.

Nasim es hamachlokos batzad v’nisached yachad sviv hamatara hayechida, netzach Yisrael. We put all disagreements to the side and unify together around one goal, Netzach Yisrael, the eternity of the Jewish people. The eternity of this idea of what we represent. And when I listened to this of nasim es hamachlokos batzad, all the disagreements, all the divisiveness, all of the looking over the shoulder, who’s doing it better, who’s more authentic, who’s more real.

And for one moment, let’s unify around the really grand idea of Netzach Yisrael, the eternity of the Jewish people, which to me is not just about Jewish perpetuity, about making sure that we have Jewish grandchildren. It is that, but it’s so much more than that. What it really is is saying in this moment right now there should feel Netzach Yisrael. We should feel eternity of the Jewish people.

The notion of the eternity of the Jewish people is not just the idea that the Jewish people are going to survive all of the enemies and all the persecution and all of the suffering. It is that no matter what happens to us, we will never completely lose our grasp on eternity itself. We are the people of eternity. We are the reminders to the world of a purpose to creation itself, of how to find meaning in our lives and how to build a purposeful life.

society. And in moments of exile and suffering, that grand idea and vision of eternity and transcendence to the world can sometimes feel diminished and small. But there are moments where we’re able to peek and get a vision of that eternity. And I think sometimes when we reflect on loss, when we reflect on that real underlying drive that animates and unites all of humanity, I think those are moments where we can grasp a little bit, a little bit onto that eternity that is infused in our lives, that is present in every breath.

And it’s that eternity that allows us, nasim et hamachlokos batzad. Let’s put our disagreements aside. V’nischade yachad sviv hamatarah hayechidah. Let’s unify and unite together around the sole and essential goal.

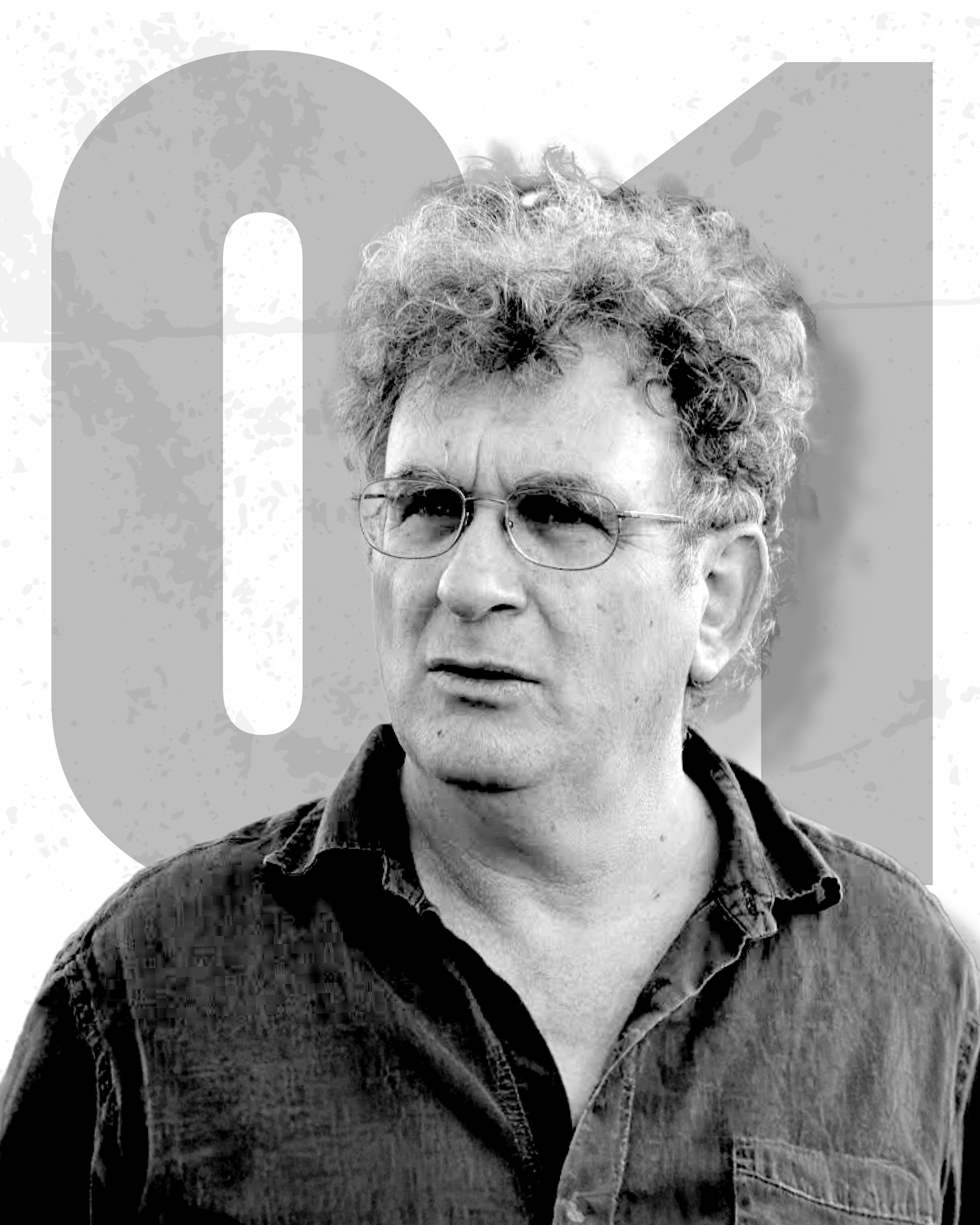

Netzach Yisrael, the eternity of the Jewish people. And it’s this goal and the very words of Gam ki eilech b’gei tzalmaves, even though I walk in the shadow of death, that I think serve as the perfect introduction to our guest today, who is somebody who is so incredible in the way that she preserves not only the legacy of her heroic husband, but takes loss and instead of feeling diminished, uses the loss to ignite an urgency to sanctify and elevate and unite the entirety of the Jewish people into that sole, most essential goal of Netzach Yisrael, that we are always connected to eternity. And today we are speaking to Hadas Hershkovitz. Hadas’s husband, Yossi, was killed in Gaza in November of 2023, and he left behind an incredible family, an incredible legacy of kindness, of Torah, and leadership.

And speaking to Hadas and listening to her humanity, her vulnerability, but also the way that loss has actually expanded her view of the Jewish people, have ignited the urgency with which she elevates the Jewish people, is something that I think as a model of loss to think about of how we take our very personal loss and instead of becoming smaller, we become so much bigger. And I’m so grateful to Hadas for sharing her story, and I’m also grateful to my friend, Yigal Sklaren, and the administration at SAR, where she served as a teacher. She was in the States a few months ago, which is when we recorded this interview. And I was just so moved by what she was doing at SAR.

She came to SAR, which is the Yeshiva High School in Riverdale. It’s also a day school and an elementary school. And her husband, as you will hear, the song that he was singing and that he put words to as they were entering was the words of Gam ki eilech b’gei tzalmaves. Even though I walk in the shadow of death, lo ira ra ki ata imadi.

I will not fear because you are with me. Or, or, as we discussed, ra, the real evil is ki ata imadi, you’re with us in exile. And to me, what Hadas and the legacy of her incredible husband Yossi represents is learning how to transform the anxiety and the pain of exile, of that feeling of Gam ki eilech b’gei tzalmaves, that feeling of being on the road, on that shadow of death, surrounded on all sides by adversaries and and bad possibilities and plan Bs and plan Cs and feels like there’s no way forward and transforming that experience and that journey into a song, into something that can be elevated, something that even the ata imadi, our immutable connection to God remains with us. And as you will hear, her vision, her compassion, and her hope, even in the face of loss, even in the face of pain, and even in the face of suffering, is a reminder that just because we’re in exile, it doesn’t mean that we can’t have a redemptive idea of hope.

It doesn’t mean that we can’t use our religious imagination to hope for a redemption that will not only take away our suffering on an individual level, but alleviates the suffering of existence itself, of humanity. humanity, that each of us, both collectively and individually, should be able to taste that song of Gam ki elech, that confidence of Gam ki elech, while also serving to expand and sanctify the Ata imadi, our vision of God and our vision of redemption. It is my absolute privilege and pleasure to introduce our conversation with Hadas Hershkowitz. It is really a privilege and pleasure to be sitting here with Hadas Hershkowitz, who is in very briefly from Israel, but has really an incredible story and experience.

Hadas, thank you so, so much for joining us today.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Thank you. Thank you for the opportunity.

David Baskevkin: So, I want to begin with a video that I saw of your husband, of blessed memory, Yossi.

There’s a video of Yossi right before he goes out to war where he is talking to his students. This is like right after, this is probably within the week almost of October 7th. You could probably get the exact date and it’s before Shabbos Bereishis. So, I’m trying to think where that was in time-wise.

And he’s trying to inspire and give some values and some meaning to the moment that he’s in. And he specifically makes note in that moment, and it like struck me, where he says, you know, we’re not left wing and right wing, we’re not chiloni versus charedi versus dati. Like it, it’s not that. We’re Am Yisrael.

We’re one nation, we’re one family. And I’m curious, why do you think that was his message at that moment going into the war? I mean, we’re now over a year later, two years later almost.

Hadas Hershkovitz: A year and a half, yeah.

David Baskevkin: A year and a half.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yeah.

David Baskevkin: And it doesn’t feel that way anymore. It doesn’t feel like as much like where one, there’s a lot of divisiveness that has bubbled up. Tell me, let’s go back to that moment.

Why do you think that was the message he was giving his students before he leaves to Gaza?

Hadas Hershkovitz: So I want to go back to October 7th. We woke up in the morning and we were supposed to kiddush. Yossi was Chatan Torah a year before, and we had to, we wanted to do the kiddush, and our son was very sick a few months before. So, we started to get ready to the kiddush and then 8 o’clock, Yossi went outside to shul.

And after two seconds, he went back and he looked at me and he said, \”Das, this milchama.\”

David Baskevkin: He said it again?

Hadas Hershkovitz: Das, this… my name, Das… Das, milchama.

David Baskevkin: Oh, he called you Hadas, Das.

Das, milchama. There’s a war.

Hadas Hershkovitz: There is a war. And it’s unbelievable that Yossi realized so early that we’re in a very serious and bad situation.

And I think that he realized because a year before the war, the situation between the milchemet achim, the situation in Israel…

David Baskevkin: The judicial reform.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yeah.

David Baskevkin: Which tore the country apart.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yeah.

David Baskevkin: Just months before.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yeah. So Yossi took it very, very serious.

And he tried to find a way to to change and to to bridge and to, yeah, to make keiruv levavot. Yossi was a person of connection. And on April before the war, I have message that he writes, \”We’re gonna get from the Hakadosh Baruch Hu, makah kasha.\” And in the end, it’s gonna be okay, but we’re gonna have our punishment. And Yossi felt that something need to change.

And I think that when he heard the bombs from Gaza, 50 kilometers kav aviri, I don’t know how to say it, from our house, he understood very fast that this is serious. And also Yossi was very connected to the Jewish history. And he searched the Holocaust and he found roots for so many people, their family roots. And I remember that he, he told me, \”Listen, I’m thinking about our grandparents.

And I have to go to fight for them also. They survived the Holocaust. They wanted to establish our country. And I have to be there.\” I said, \”Listen, you’re 44, you have five kids.

Everyone has their own kids, but you have 600 students that needs you.\” So I wanted him to… the rebbe in…

David Baskevkin: He was a principal in a big school in Jerusalem and I wanted him to think where people needs him more. And he said it’s not a question.

This is what I should be doing now. I have to go fight and help our brother on Gaza border and I have to try to save the hostages. He realized very early in the morning that there are some hostages and Yossi has the ability always to to see, you know, the big picture.

Hadas Hershkovitz: But you didn’t initially, you wanted him to stay.

David Baskevkin: I I wanted him to do whatever he think that the most important to do and I just I thought that he has so many students that need him. So, and he had celiac and you know, he was 44. It wasn’t our story.

Hadas Hershkovitz: He’s not a kid anymore.

David Baskevkin: Yeah. And he said it’s not a question. And then he he he took the kids and he explained them that it’s going to take time. It was 10 o’clock in the morning.

And he spoke about the chagim, Chanukah, chag ha’or, ve’Purim and Pesach, chag ha’cherut. And I looked at him…

Hadas Hershkovitz: So he took your children?

David Baskevkin: Yeah.

Hadas Hershkovitz: And he started talking to them about all the Jewish holidays.

Not not just we were right on Simchat Torah.

David Baskevkin: Right, correct.

Hadas Hershkovitz: He started talking about Chanukah.

David Baskevkin: Chanukah, and I looked at him and I felt like his face, he was so into it.

He understood that we live in a historical moment and my heart broke at that point. And Yossi left and I I stayed with the kids, with the siren, and we had to lie on the floor.

Hadas Hershkovitz: When he left, he wanted to couch and frame his leaving within Chanukah and Purim, all of the great fights of Jewish history where we’re really kind of seeing world history unfold. He saw this is this moment too.

This is our Chanukah. This is our Purim.

David Baskevkin: Yeah, he he, I think he tried to connect the the kids to the situation and to explain that he he’s going to to fight for our our country, for them, for our…

Hadas Hershkovitz: Our survival.

David Baskevkin: Yeah. And at that point, a week after the war started on Gaza border, Yossi found the strength to record this video. And I found so many versions of this video and…

Hadas Hershkovitz: Who did he send it to?

David Baskevkin: So he sent it, he posted on Facebook for the students.

And I remember that I sat on the couch on Friday and I watched this video and I couldn’t believe how Yossi at that moment on Gaza border and he knew that he’s going to go inside in a few days, found the way to speak education and find a way to to transform the tragedy into a growth and healing moment. And it’s it’s so Yossi, it’s unbelievable. And so many people saw, watched this video.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Even on the border, he was still an educator.

David Baskevkin: Yeah.

Hadas Hershkovitz: He’s still educating. It’s something that we need so desperately in this moment, which is that not that we so many of us just consume this through media, through newspapers, and we don’t appreciate that this is a Purim story. This is this needs to be read like the Megillah, not like not like the New York Times, not like the Washington Post or even Haaretz or the Jerusalem…

This is a Megillah that’s unfolding.

David Baskevkin: Right. And Yossi spoke about ein chiloni, ein dati, ein s’molani, ein yemani. Slicha, ein yemani, ein s’molani, ein charedi.

And I think that he carried with him the year before the war and he he he felt that this is the moment that we need to be united. And I think at that moment, he become a sign of, ech omrim? K’ilu semel l’tikva v’achdut.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Like a symbol of hope, a symbol of…

David Baskevkin: At that point, he become a symbol of hope for so many people and we needed it so much at that point.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Desperately, and we still do. Unfortunately, this is not a story that, you know, has a trajectory of just hope, it doesn’t just go up. Your story takes really a quite a tragic turn where Yossi just a few weeks out when he was in Gaza was was killed.

David Baskevkin: Right.

I just want to say about the the the movie that it’s so moving and I it was moving then and I couldn’t watch this video for more than a year. And before Yom HaZikaron, this Yom HaZikaron, I watched it…

Hadas Hershkovitz: For the first time?

David Baskevkin: for the first time. And it’s unbelievable how much we need this message now, a year and a half after the war.

It’s so important and so meaningful and so powerful to have this message.

Hadas Hershkovitz: I want to come back to that message later because the fact that we still need it desperately means that we didn’t fully hear the message. So I want to come back to that kind of like where we are now, but to get there, take me through how you learned that Yossi was not going to be coming home from Gaza.

David Baskevkin: So Yossi and me were very connected.

We had a very special relationship and

Hadas Hershkovitz: Where did you meet?

David Baskevkin: What?

Hadas Hershkovitz: Where did you meet?

David Baskevkin: We met, my friends, my best, one of my, my friend sent, set us up. Actually, my friend is Elisha’s Medan’s sister.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Oh.

David Baskevkin: And Elisha is Yossi’s, was Yossi’s best friend.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Very sweet.

David Baskevkin: So it’s part of our story from the beginning. And and I felt Yossi. I felt that Yossi feel that he’s going to be there and to give everything that he can.

And I know Yossi that all the time, everything that he does, he does on the best side. And I didn’t know but Yossi was the first one with his team to get inside Gaza from the north side. And I can imagine what Yossi felt that he knew that they gonna be the first one. No one knew how it’s gonna look like.

No one knew what the Hamas prepare for the chayalim. And he carried with him this feeling. And he was ready to sacrifice himself for our country, for for our nation, for our people. And I think that a month after Yossi was killed, November 10th, but throughout this month, we barely spoke.

But I took the kids to the base on Friday, second Friday, Friday to see Yossi. And we had just few minutes and we came. And I saw Yossi and he looked at the kids, it was so hard. And he started to sing machshavot tovot.

I have, I never take pictures, I never take videos, but I took so many pictures and I video almost everything.

Family: Dibburim tovim, ai yai yai yai, ai yai. Ai yai yai yai. Machshavot tovot, ai yai yai yai, ai yai yai yai, ai yai yai yai.

Dibburim tovim, ai yai yai yai, ai yai yai yai, ai yai yai yai.

Hadas Hershkovitz: He had a real optimism. You were telling me before we recorded that you know, as a family, Fridays were like family day. That was like a day that was very important where you would spend time with family.

David Baskevkin: Right.

Right, but Yossi, I think I felt that Yossi want to tell the kids, machshavot tovot, it’s going to be okay. Even it won’t be okay, so you need to have machshavot tovot. And he sang it again and again and again.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Machshavot tovot meaning like optimistic thoughts.

You have to like get your mind in a

David Baskevkin: You know this song?

Hadas Hershkovitz: Sure.

David Baskevkin: So I have the video I’ll give them for you. And so I felt Yossi. And then, and then a week after, Yossi called me on Friday night.

We finished the Shabbat meal and the phone rang and I look, I saw Yossi. And I picked up the phone and he told me, listen, I don’t have time, but I just want to tell you that I’m going inside soon and I’m going for unlimited time. These his words. And I remember that I couldn’t speak.

And I wish him hatzlacha and and then, back then, no one knew what’s going to happen. It was, everything was unknown. The news didn’t speak about what’s happening in Gaza, so it took few days for us to hear that Tzahal got in inside Gaza. And I heard in his voice when he said for unlimited time that he feels that he is afraid.

And I’m trying to, so then he went inside Gaza, and I was very worried. And usually, I’m not a, you know, a, an anxiety person?

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yeah.

David Baskevkin: But I had like strong feeling that it’s not going to be good.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Good.

David Baskevkin: And so it’s, it’s a long story, but my, my brother fought with Yossi. And his son was born with a serious, um, uh, heart, um,

Hadas Hershkovitz: condition.

David Baskevkin: condition, yeah. And he was in intensive care in the hospital.

And Yossi told to my brother, \”Don’t, stay with your wife, stay with the baby.\” But my brother joined him while they went inside. And we had the brief and we thought that he won’t come. And suddenly he appeared like in the movie.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Your brother.

David Baskevkin: My brother. And he came and he couldn’t look, looked at me, look at me?

Hadas Hershkovitz: He couldn’t look at you.

David Baskevkin: He couldn’t look at me. And he gave me small notebook, small pinkas.

And he said, \”Take this from Yossi.\” And went, and he was very upset. And I remember that moment that I got this, uh, not, small notebook. And I opened it and I saw a letter for me. And then for each one of the kids, and then for his parents.

And I remember I didn’t read the letters.

Hadas Hershkovitz: He wrote a letter to each of his children, to you, and his parents?

David Baskevkin: Yeah.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Thinking that I may not come back.

David Baskevkin: Yeah.

And I remember I took this notebook, I put, put it in my bag, in my, um, um, tik.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yeah. Bag.

David Baskevkin: In my bag.

And I, uh, I said, I can’t understand that he did it.

Hadas Hershkovitz: You were upset at him.

David Baskevkin: No, but it was part of my feeling that I felt that Yossi felt that something gonna happen. I just want to add before, Yossi was a chazan.

And he, he prayed tefilat Musaf at Yom Kippur, and he was screaming. It was such a powerful tfilah. And some people sent me messages motzei Yom Kippur, if Yossi is okay, if everything is okay. And when Yossi went, I felt that maybe this tfilah was part of his feeling.

So I carried everything with me. And and it just, you know, every time something else.

Hadas Hershkovitz: And this was darling before October 7th.

David Baskevkin: Before October 7th.

But in my mind, I like, I

Hadas Hershkovitz: You heard the echoes of those prayers.

David Baskevkin: Right. So Yossi sent me the letters and

Hadas Hershkovitz: Did you give them to your children?

David Baskevkin: No. I didn’t give them anyone.

And I, uh, I didn’t read the letters.

Hadas Hershkovitz: You kept it a secret.

David Baskevkin: Yeah. And I got a video, short video.

They didn’t have the phones, but they had camera. And someone that went outside sent me, actually it’s Golan Vach, he sent me, um, small, a short video from Yossi. I have it. And when I watched it, I knew.

He looked like he was very, very, um, merugash.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Emotional.

David Baskevkin: He was very emotional. And he couldn’t stop talking.

And he spoke about, uh, about, uh, that he want us to be happy. And this was one more piece that I had, I said to my friends, \”Look, I know he feels something bad.\”

Hadas Hershkovitz: What do you think it was? Meaning, it’s so interesting the person who was emphasizing and singing machshavot tovot with your kids, something changed when he came into Gaza. What what do you think it was that all of a sudden?

David Baskevkin: I think he carried both. He was, he really want, he really, he was an optimistic and he tried to fight these thoughts.

But he knew that he going to be the first one to get inside Gaza. So he knew that something might happened. And he took it into consideration. And in the end of it, we had anniversary in the same week.

And Yossi recorded through the red, red phone. It’s a special phone that they have to connect with IDF inside Israel. And he found someone that recorded through the phone, uh, et ha’kesher, ech omrim kesher?

Hadas Hershkovitz: Connection?

David Baskevkin: No, et ha, like shel ha’tzava.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Like the, the walkie-talkie, or yeah.

David Baskevkin: Yeah. So he found someone that recorded it and send it like voice. Wish me a happy anniversary. That was also the same week.

And then on Friday, I woke up and I was a mess. I felt so bad.

Hadas Hershkovitz: You felt dread.

David Baskevkin: Yeah.

And I tried to help myself. I remember I went to Jerusalem to meet a friend, and I told her that I have such a bad feeling, and I’m trying to, to, to not feel that way, but it’s, it’s, it’s bigger than I could do.And I came back home. Shabbat started early, like about 3:30. And I came back, it was 3 o’clock.

I sat on the sofa, and I remember that I have such a bad stomach pain. And my neighbor just came in to take something and I grabbed her hand and I asked her if she can sit with me. And I said, I, I, I don’t know what to do. I feel so, something bad is happening.

And I knew that I need to, uh, light the candle and to take big breath and, and, and be there for the kids. And I lit the candle and I asked Hashem to help me.Then the kids went to, to shul, and I asked Be’eri, my oldest.

Family: How old is your oldest?

David Baskevkin: Now he’s 17.

Hadas Hershkovitz: And her, and your youngest is?

David Baskevkin: My youngest is four.

He was two and a half. Yeah.

Hadas Hershkovitz: So it was a big…

David Baskevkin: Yeah, and I have five.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Amazing kids.

David Baskevkin: Yeah.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Bli ayin hara.

David Baskevkin: Yeah, bli ayin hara. And I asked my, uh, oldest, Be’eri, to take my youngest, Neta, to shul.

And I, I, I said to him, and I never did before, \”Take him. Try that he gonna sit with you, pray.\” And they came back from shul and, um, my neighbor invited us for a meal. And we started so that Shabbat and I tried so much.

Hadas Hershkovitz: To get into…

David Baskevkin: Yes.

Hadas Hershkovitz: The Shabbat mode, the tranquility, the serenity.

David Baskevkin: Yeah. And actually, it was a good se’udah. The kids were playing.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Playing. Yeah.

David Baskevkin: Full of life. And suddenly in the middle of, um, Shabbat dinner, someone knocked on the door.

Family: At your neighbor’s house?

David Baskevkin: Yeah. And we opened the door, and I saw the three officers. So they knock on my door and I knew. Immediately.

And I just, immediately.

Hadas Hershkovitz: When I heard the knocking. You knew from the knock.

David Baskevkin: Yeah, I knew from the knock that it’s coming.

And I remember I told them, \”I’m so happy for you that you didn’t know Yossi. Get to know Yossi. Because if you would know him, you won’t be able to tell me what you have to say.\”

Family: You said that before they said a word?

David Baskevkin: Before. And then they had to, they, they have a like formal way that they have to…

Hadas Hershkovitz: There’s a protocol for how they tell.

David Baskevkin: Protocol for how to tell. Um, so they sat with me and they said, \”Yosef Chaim, Yossi, neherag ba’krav.\” And I remember that I felt that it can’t be true. Like I knew that it’s gonna come, but, and I said that until today, a year and a half after, I still, it’s hard for me to, to accept this gzerah and to accept that Yossi’s not here. And I told them that it’s going to be a mega pigu’a.

Mega pigu’a is like, it’s gonna… affect so many people in so many circles, and I just started to think about family, friends, community, 600 students. And I had an hour and a half until they found Yossi’s parents to to tell them this terrible announcement. And I was in my they took me to my house and I had to tell each one of my kids. And I they they

Hadas Hershkovitz: Did you tell your kids separately or together?

David Baskevkin: No, they brought one after one, and they needed me to say the the

Hadas Hershkovitz: Protocol.

David Baskevkin: the protocol.

Hadas Hershkovitz: You had to say?

David Baskevkin: Yeah, I had to say Abba neherag bakrav. And I sat with with my kids. And I knew that I’m going to to tell them the worst thing that I could.

And then so fast everyone started to hear about it. It was Erev Shabbat, but it spread out in Jerusalem. Yossi’s parents live there and the school and during Shabbat it was it was terrible, but I just wanna come back to what happened to them. So while I sit on my sofa and and felt the stomach pain, actually, we knew that they were supposed to go out to rest a little bit, but the intelligence got an information that hostages maybe said near there in a mosque, in the mosque.

So they got just one more mission.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Before they?

David Baskevkin: Before, before. And then they had to go and found a tunnel. And on on knisat Shabbat, exactly 3:30, they Moshe Leiter announced in the in the kesher, \”We found the tunnel, Shabbat Shalom.\” And then there were there was a explosion.

And Yossi and three more friends were killed and six injured very, very badly. Most of them lost their legs. And actually Yossi didn’t die immediately. He it took a few minutes.

He lost his leg and he lied next to his best friend, Elisha Medan, that thanks God, survive and he just this Yom Ha’atzmaut lit a masua

Hadas Hershkovitz: in Israel, how it’s called? Like the one of the torches or?

David Baskevkin: No, he lights in the in the big tekes in Yom Ha’atzmaut.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yeah, yeah, yeah, one of the candles.

David Baskevkin: Yeah. And and after a few minutes, Yossi passed away.

And my brother that fought with them, he was part of the medical team, and he needed to take care of them and spend the last few minutes with Yossi.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Your brother?

David Baskevkin: Yeah, my youngest brother.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Wow.

David Baskevkin: Yeah.

And then the funeral took place Sunday. More than 20,000 people came, and it was very long. It was about three, four hours. We sang a lot.

Hadas Hershkovitz: What did you sing?

David Baskevkin: Yossi was a musician. He played the violin. And the violin was part of his life. Maybe we’ll talk about it, it’s a new piece, very important piece.

And we brought Yossi’s violin and his violin, his teacher, violin teacher, played in his violin, and we had some more friends played and just we sang and sang.

Hadas Hershkovitz: You brought Yossi’s violin to the funeral?

David Baskevkin: Yeah, to the funeral. Yeah. And it was before the October 7th, levayot needed to be very fast.

So Yossi’s levaya, he was one of the first one that died after that was killed after October 7th. So, thanks God we had the time. Actually, he was the third one to be buried this that day. Moshe Leiter buried before and another soldier before.

And the officer came to me in the end of the levaya and they said, \”You said it’s gonna be mega pigua,\” and we believed, but we didn’t understand what kind of person Yossi was and how it affect so many people. Then we had the the the shiva. And we had a very special moment when Golan Vach that fought with Yossi came to the levaya. came, came to the shiva.

Shiva call. And he said that he has something, something very important to tell us. And we sat there and so many people were there around. And then he he told us that that he met Yossi and Leiter and Elisha on Gaza border before they went inside Gaza.

And he was b’chlal commander of a different yechida in the in the army, but he decided to join them for 10 days. And Golan Vach is a musician. And he said that for the, for ten, during these 10 days, he heard Yossi humming a tune again and again and again. And the night before he went back to Israel, he he was on shmira, 2:00 at night, and Yossi went around and around and sang this song.

And Golan asked Yossi, \”What are you humming?\” And Yossi said, \”It’s a tune that came to my mind while I got inside Gaza. I felt like in ma’amad Har Sinai, kolot u’vrakim. And this tune came to my mind, and…\”

Hadas Hershkovitz: Like a revelation.

David Baskevkin: Yeah.

And the words…

Hadas Hershkovitz: On Har Sinai he said like with the thunder and lightning of Sinai, it was like a moment of revelation.

David Baskevkin: Think about the darkness and the light and the and the fire and… And Yossi felt it was ma’amad Har Sinai. I think b’chol ha’muvanim, like he felt like it’s, it’s…

Family: There’s a moment where it felt October 7th was a revelation to the Jewish people. We were reminded.

It was revealed to us what we already had.

David Baskevkin: Yeah.

Hadas Hershkovitz: And that’s when they recorded, there’s a recording of him that…

David Baskevkin: No, so, so, so then Golan asked him, \”Sing it to me.\” And Yossi sang the the song with the words from Tehillim, \”Gam ki elech b’gei tzalmavet lo ira ra ki ata imadi.\”

Hadas Hershkovitz: Which I’ll allow me to translate. Gam ki elech b’gei tzalmavet, even though I walk in the in the shadow of death, lo ira ra, I will not fear any evil or any suffering or any pain, ki ata imadi, because you, God, are with me.

David Baskevkin: Ach tov va’chesed yirdefuni kol yemei chayai.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Ach tov va’chesed, that only goodness and kindness should pursue me, should run after me my entire life.

Family: And that’s what he’s saying.

David Baskevkin: That that was the words.

And he sang a few times and Golan said, \”Sing it again, sing it again.\” And that’s it, Golan went back to Israel. And Golan told us that during Shabbat, he heard about the terrible news, and he was crying not only because of the death, because he couldn’t remember the tune that Yossi taught him. And he said that during the levaya and the niggunim there, suddenly it came to his mind.

Family: He remembered it.

David Baskevkin: Yeah. He went outside and he recorded himself. And a day after, he came to the to the Shiva call with a guitar, and he played and he gave us this gift, this, this powerful…

Hadas Hershkovitz: It’s his final song, his mantra.

David Baskevkin: Yeah, mantra.

b’yom shishi ba’laila, levad ba’cheder v’im kol ha’mavet ha’ze v’ha’ovdan ha’ze. Davar she’hachi metzaer oti she’ani lo zocher et ha’shir. ba’halvaya azkamah.

Hadas Hershkovitz: And I feel that it’s this is an unbelievable story. And I spoke with Golan and also Golan felt that Yossi wanted to pass it to Golan.

Golan said 2:00 at night. and he goes like around and around and trying to to to take his attention. And I know that Yossi wanted to pass this tune. And I also know that Yossi chose these psukim because he was afraid.

And he wanted Hashem to be with him and he wanted Hashem to give him koach. And he wanted the chizuk and it’s also, you know, the optimistic and the like he tried whatever he could to get strength from Hashem and from this historical moment. And this uh this tune is just unbelievable. We got thousands of bituyim from all over the world.

People playing this song in shul, in tkasim, in in schools. And I think that it’s kind of the Ani Ma’amin story, you know, from the Holocaust.

Family: Yeah. To find to find the song that captures the moment, that captures the strength that we’re looking for.

Allow me to ask, I’m I’m I’m so curious and you kind of left it hanging. Did you ever open up the notebook?

Hadas Hershkovitz: Of course. After the shiva, I I opened the the notebook. Actually, on Thursday, before a day before Yossi was killed, we knew that Yossi might come back.

And I was afraid that maybe if he will found found out that I didn’t

Family: Would get offended.

Hadas Hershkovitz: I didn’t read and I didn’t give gave, I didn’t give his his uh parents the the letter, so maybe he will be, you know, upset or…

Family: Upset or

Hadas Hershkovitz: I will feel like, you know, we both Yeah. Like danced at this um, and so I remember 7:00 in the morning, I took a picture and I sent his parents this letter.

And it’s unbelievable letter, actually. Uh we posted uh the rest of the letters we kept to ourselves, you know, for me and for the kids, but this letter was

Family: To his parents. You did share it.

Hadas Hershkovitz: to his parents.

Yeah. And and I also from the way that he wrote this uh letter, I feel that he he knew that maybe uh it will uh we’re gonna post it. It was a big and powerful message too.

Family: Do you remember what it what it was?

Hadas Hershkovitz: So he wrote to his parents that he thanks them on the way that they educated him to ask the question what he should be, not what he should get.

ella what he should be doing what he should be giving, not what he should be receiving. the the the like mah ani yachol, mah ani yachol latet b’chol rega v’rega

Family: What can I give at each and every moment.

Hadas Hershkovitz: l’maan ha’am v’ha’medina sheli.

Family: in order to support my nation, my people, my my state.

Hadas Hershkovitz: The state of Israel, the people of Israel. And this was Yossi. He always

Family: Can you please repeat that one more time in Hebrew? It’s very beautiful.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Ken.

hu katav shehu modeh l’horim shehem chinchu oto lishol et ha’she’elah lo mah magi’a li, ella mah ani yachol la’asot b’chol rega v’rega l’maan ha’am v’ha’medina sheli.

Family: What can I give at any moment for my nation, for my people. That is that is very powerful. I I want to like shift for a moment, like the strength of Yossi.

David Baskevkin: is so awe-inspiring and so heavy.

And here we are a year and a half out, and like when I watch that video, I remember those moments. I I think I may have even seen that video because it circulated.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Right.

David Baskevkin: And people saw it.

And you know, we’re we’re we’re almost two years into this, and it feels like it’s a new paradigm. And in a lot of ways, everyone now is maybe diagnosing the same problem of like we need more unity, we need more Yiddishkeit, and more sense of Jewish peoplehood and nation, and we’re going around. And yet, I’ll be honest, I’m looking around and maybe it’s because I’m not thinking enough machshavos tovos. I’m not thinking positively enough, but I’m worried.

I don’t I don’t see it. I I am worried about American Jewry, North American Jewry. Um, I’m worried that we don’t understand the magnitude of this moment and the opportunity of this moment. I’m worried about the divisions that continue to exist in Israel.

I think the division between the Chareidi community, the Dati community, the like we everyone needs to contribute to this, to this, to this model, to this country, and figuring that out without making one community, you know, feel like they’re being, you know, hounded or their Yiddishkeit can’t continue. These are questions that like I I sit up at night trying to figure out, I don’t see the path. Like I I I I’m genuinely worried. And do we have, and when I say we, I mean the Jewish people, do we have the capacity to continue this? Do we have the shoulders? So I’m curious from you, you know, you have the image of Yossi, and then you have the the pain that you’re living with.

How do you still find strength, if you even do, to to continue Yossi’s legacy, that optimism, the machshavos tovos, and not get crushed and lost in the gates, tzalmavet, in the, in the shadow of death?

Hadas Hershkovitz: It’s such a good question. It’s and this is my, you know, my life journey now. And I’m trying to, um, to find the way to continue Yossi, but I want to say that I think that we have, now it’s not just what we want to do. We have the obligation for the chayalim, for the gibborim that sacrificed themselves for us, to do whatever we can to make the world better, to make, to do, you know, to to to unite it, to, ech omrim la’asot…

David Baskevkin: You could say in Hebrew, I’ll always translate.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Ken. Achrayut musarit. Like a…

David Baskevkin: Ethical responsibility.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yeah, for them. To to to to make sure that we we’re doing whatever we can not to come back to October 6th and the situation and and and I think that it’s a it’s a it depend on each one of us. And a story came up to my mind just the way how Yossi tried to make this change.

So I remember that I I told you about the tefilat Yom Kippur, and that Yossi was very upset for from the situation of the milchemet achim, of of the Judaism, of of everything.

David Baskevkin: People were fighting with each other. It was about like the vision of the state of Israel and they were…

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yeah, and he barely couldn’t, could not sleep.

Mamash kacha. B’Ivrit omrim zeh hadir sheina me’einav.

David Baskevkin: Mhm.

Hadas Hershkovitz: And I remember that, uh, when on Motzei Yom Kippur, when we heard about the situation in Tel Aviv with the mechitza, you remember?

David Baskevkin: Yeah, sure.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yossi…

David Baskevkin: Just for our listeners, what happened is is they tried to set up a Yom Kippur davening in one of the public squares in Tel Aviv, and it was like such a tragic fight that anybody who was watching, at least myself, was like… we got to learn how to avoid this, but they got into a fight ’cause they wanted a mechitza for a traditional davening service on Yom Kippur, and the municipality or somebody interceded, and they got rid of the mechitza. And then you had Jews fighting amongst each other on Yom Kippur, which was like it knocked the, it knocks the wind out of you.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Mamash kacha. And I think that we all felt that it it was like summary of the year that we’ve been through before.

David Baskevkin: The symbol for what we’re dealing with.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yeah.

And I remember that Yossi was so upset, so upset. And the day after, we drove together to work, and Yossi told me, I feel that I have to find a way that the student will be part of keiruv levavot. We can’t stand, you know, we have to do something. We have to find a way that each one of us…

David Baskevkin: Proactively.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yeah, exactly. And he went to work, I went to work, and I picked him up a few hours later, and he said, I have an idea. So I asked him, what is it? So he said, I want to write a Sefer Torah for the shoter Chen Amir. Chen Amir was a, um, shoter, cop that saved so many people in August, a month before Yom Kippur in Tel Aviv during Shabbat.

And I said, okay, and why, why chose Chen Amir? So he said the way that he, um, chatar l’maga. How you say it in English? Like he jumped and to save. He was proactive…

David Baskevkin: Yeah.

Hadas Hershkovitz: for, to, you know, for to be able to save so many people.

David Baskevkin: Jumped into action.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yeah, jump, exactly. And his personality touched me. And it was in Tel Aviv.

So he thought about a way to, you know, to take Tel Aviv…

David Baskevkin: To bring people together in Tel Aviv after what happened.

Hadas Hershkovitz: And I ask him why Sefer Torah? So he said, Sefer Torah, it’s something that, you know, connected all of us. It’s our roots in our, it’s our netzach.

David Baskevkin: Our eternity.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yeah. And I said, okay, how are you gonna do it? It’s it’s expensive. So he said, I have a plan. I want the student to work so hard and feel it in their hands.

And I want them to pick up recycle bottle, um, plastic bottles for recycling and to work very hard to collect the money, to raise the money for the Sefer Torah.

David Baskevkin: From the recycled bottles.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yeah. So I opened the calculation, calculator.

David Baskevkin: I’m thinking in my head too.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Calculator, and I showed him, I said, listen, it’s a nice idea, but it’s, it’s not going to work. So he said, okay, so they will do some work project in…

David Baskevkin: There’s a whole Seinfeld episode. My listeners are know, you know, do you know Ata Ma’kir Seinfeld?

Family: Ken.

David Baskevkin: We like Seinfeld. He he’s fighting for the Jews also in his way. And he has a whole episode where they in in America, on the when you recycle, so you get, normally you get five cents. It’s like five agorot.

But there’s one or two states in the entire America where you get 10 cents. So the whole episode is trying to figure out how we could, but without the cost of gas that will double our money by getting, bringing all the bottles to this, to this country. It’s funny, your husband had a…

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yeah, so maybe he watched Seinfeld. It could be.

He watched Seinfeld. Yeah, he did.

David Baskevkin: So he said…

Hadas Hershkovitz: So, um, so I opened the calculator and they said, so he said, I told him, let’s wait. Let’s make a plan, finance plan for this, uh, project.

So he said, it’s too late. Why? I called his parents already. And what did you tell them? I told them that I wanna write Sefer Torah for their son. And they didn’t understand in the beginning what I I want from them.

So they asked, why, what you need from us? So I answered, I don’t need anything. I just need you to be, uh, that you’re going to be with me with the idea of keiruv levavot. And they…

David Baskevkin: To bring hearts to connect hearts to Yiddishkeit.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yeah.

Not just to Yiddishkeit, to connect, for to be connected.

David Baskevkin: Chiloni v’dati’im.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Connected.

David Baskevkin: Ken.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Yemini v’smolanim, connected.

David Baskevkin: Ken. And they said okay.

Hadas Hershkovitz: So I said, wow, okay.

And we got home, I forgot about this story. During…

David Baskevkin: shiv’ah call, during the shiv’ah, suddenly it came to my mind and I didn’t remember exactly what he said and like it was the whole balagan. And the day after the shiv’ah, I found their Amir, Chen Amir parents’ phone number. And I called them and I said, maybe a principal from Jerusalem spoke with you about the Sefer Torah.

So they said, yes, what you need. So I told them that I’m Yossi’s wife and that he was killed last week. And they were in shock. And they needed a few minutes so they said we’re gonna call you back.

And they called me back after a few hours. And Chen Amir’s sister told me that Amir, Chen Amir, Chen Amir’s family lives in Kibbutz Re’im in Gaza border. And they were 26 hours in the in the mamad. And they survived October 7th.

And she called me from Eilat. They were, you know, they needed to move from the kibbutz.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Sure.

David Baskevkin: And I couldn’t believe because Yossi, when he thought about the idea of the Sefer Torah, Kibbutz Re’im wasn’t, you know, in the map.

Family: He was telling us.

David Baskevkin: Yeah, it was Tel Aviv, but it was unbelievable that his family lives in Kibbutz Re’im and survived. Their neighbors were murdered. And she told me that this, a day before Yossi called them, she decided on the first time to have Tefillat Yom Kippur in the kibbutz.

And because she…

Hadas Hershkovitz: For the first time?

David Baskevkin: for her brother. It was a month after her brother was killed and she felt that they need to have minyan. And in the kibbutz they said, why, why you need it? We don’t need shul, it’s s’tam balagan.

And she fought for, for…

Hadas Hershkovitz: This person’s parents who he called…

David Baskevkin: his sister. And she said that she brought minyan from Yeshivat Sderot for the first time to the kibbutz and they had minyan.

And the day after, Yossi called to tell them about the Sefer Torah. And she felt that it was a sign that they did the right thing. But she said that during October 7th, they felt that this Sefer Torah saved them, that Hashem saved them. And she said, I’m the most secular people that you can have.

But we felt that this Sefer Torah saved our life. And I think that there is so many piece of this story.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Oh, it’s incredible how the part I find so moving is that what drew him is like this divisiveness that was happening in Tel Aviv and it led in many ways, this very same family, the same child and brother, that brought in and said, let’s move closer to to connecting. Let’s bring in a Sefer Torah, it’s not so far.

David Baskevkin: Exactly, and let’s be proactive. Let’s do. Yossi didn’t speak. He, he he had a an idea, he had a dream, he just did whatever he can to start doing.

He didn’t wait. And it was so Yossi. And I think that this is kind of a way that Yossi thought how he can change the reality, how he can affect and make the, the change.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Tell me a little bit about your reality, meaning you are a mother with five children.

You know, you have a, like still like a little, like a baby, four-year-old. I also, I have a a little four-year-old, still, still little, still could wake up in the middle of the night. Where do you draw strength from to get through this? Where do you draw just capacity to have five little children? You have a life of your own. You need to take care of yourself, make sure that you’re paying attention.

Where do you turn to get support in the aftermath, after levayah, after shivah, after everybody’s singing together? Now it’s quiet and it’s you and your family and your own life. Where do you turn to get that strength now?

David Baskevkin: now. It’s very, very, very hard. We have a hole in our heart, mamash kacha.

I feel like a chatzi benadam.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Half a person.

David Baskevkin: Yeah, and I think that it’s a, it’s a fight every, every day, and it’s not a…

Hadas Hershkovitz: What do you feel like you’re fighting against inside?

David Baskevkin: I have to fight to get up in the morning. I need to, to choose in life every day.

Hadas Hershkovitz: To choose life actively every day.

David Baskevkin: Yeah, very, every day. And sometimes, few times during the day. Yossi was, he was very busy, but he always was very, dominant?

Hadas Hershkovitz: Strong.

Dominanti. Yeah, forthcoming, dominant.

David Baskevkin: In, in our, in, in k’mo babayit shelanu, yeah. He was.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Just supportive.

David Baskevkin: And it’s very hard, but I have the kids, and I feel that Yossi left me such a, such a gift with the kids. And each one of them need so, need support, and need different things. And it’s hard because it’s not a normal reality.

It’s during the war, and we need to manage, and we need to get up and, and, and to, to try to, to live. And we have to run to the shelter once in few days, sometimes every day. And the, the, the war is still happening, and they’re afraid. It’s crazy reality in Israel.

And we have crazy reality in our house, in our family, in our yishuv. Yossi was very dominant in our yishuv.

Hadas Hershkovitz: You have a very remarkable yishuv, I believe, right? You have a yishuv where, where adults who have cognitive disabilities, they’re, they’re…

David Baskevkin: Special needs, yeah.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Special needs are able to live and have work and are integrated as a responsibility that the entire yishuv takes responsibility, the community, to make sure that they’re taken care of. Not because it’s necessarily their family.

David Baskevkin: No, they are, they are not their family. Our community is about 50 families that chose to be part of this idea.

Shekol adam yesh lo makom ba’olam, and we wanted to raise…

Hadas Hershkovitz: That every person has a place. And you come from a community where, you know, to say we have a place for everybody isn’t just a slogan, it’s not just a bumper sticker. People with special needs, not family, not the children, from other towns, from other places, they have a place there.

David Baskevkin: Absolutely.

Right. They live between us in apartments, and each one of them has mishpacha me’ametzet that…

Hadas Hershkovitz: Like an adoptive family.

David Baskevkin: Yeah, yeah, they can, they come once a week for se’udat Shabbat. But they’re part of the our community, they’re part of the shul.

We have gabbai with Down syndrome, and it’s not beke’ilu. He actually really takes responsibility.

Hadas Hershkovitz: The gabbai?

David Baskevkin: There, one of the gabbaim is with, yeah, and he has his, his, tafkidim and…

Hadas Hershkovitz: His jobs, responsibilities.

David Baskevkin: Yeah.

Yeah.

Hadas Hershkovitz: This is, this, this is the nekudah. This is the point that I am envious of the people of Israel because, and something that I’ve said many, many times, in North American Jewry, it’s much easier to, I call it, there’s a word in English called gerrymandering. You can, you can draw the boundaries of the community any way you like.

So this community is for, you know, the wealthy people. This community is for the Chareidi, the frum. And this is for the secular, and this is for the special needs, and this is for the really intellectuals. And we have these communities very often where we don’t push ourselves as, as hard as I think we need to to say Judaism is for everybody.

Yiddishkeit’s for everybody and we need to find a seat for everybody. And that you have a community where young kids are growing up seeing, it changes you as a person.

David Baskevkin: Right. When we went to shlichut at SAR and in 2012…

Hadas Hershkovitz: As a couple you came with your children.

David Baskevkin: Right. We had two, and I gave birth here. We have one American.

Hadas Hershkovitz: One American.

David Baskevkin: Yeah. And when we come back, we wanted to find a place in Israel that will gonna have meaningful life. because here we felt that we have so many, we felt that it was so, we did something important. And we found this this yishuv and we came from Riverdale to this small yishuv.

We live in caravan, in very simple life. We have beautiful house, but it’s a caravan. And it’s also piece of this, you know, what we spoke about, about pashut. Pashut, lichyot et ha’chaim b’emet.

Hadas Hershkovitz: The simplicity without all of the packaging and gravitas and status, but to almost live an unmediated life, where you’re fully stepped in and fully almost like living that embodied life without chasing status. The only thing that we should have chasing us like in the song is ach tov v’chesed, goodness and kindness. Allow me to ask in Israel now, and something that I really want to understand and hear about is you have a generation now, sadly, unfortunately, that we have a generation in Israel now who are growing up without a parent. You have parents who are growing up without a child, and I can only imagine that there and maybe I’m wrong, that there are like networks where you’re where other people, other families, you know, children who have lost parents, spouses who have lost husbands.

Do you get comfort from interacting with other, um, in Hebrew it’s an almanah, like a, like a widow. Does that, you know, sometimes, and it’s always interesting, everybody has their own personality for how they mourn and process suffering and tragedy. It’s what makes us most human. Like part of coming into existence is processing the suffering of just being alive and and just going through.

And I’m curious to hear for you, how you relate because it it’s like a it’s a it’s a collective trauma. Everyone’s going through this now.

David Baskevkin: Mamash.

Hadas Hershkovitz: How do you relate to other families? It’s like, look, I just want to be with me.

I remember I asked somebody, um, who was on 18Forty, whose family, um, went through something horrible and tragic. And this mother said, I don’t want to speak to the other, it’s not for me. It doesn’t work. And I’m curious for you how you relate to the collective component, the national component.

David Baskevkin: You have such a good questions. So I never thought that I gonna, you know, communicate with the other families or widows or because

Hadas Hershkovitz: Why not? Because

David Baskevkin: because I have so many people in my life, in my life. I have a big support family.

Hadas Hershkovitz: So like

David Baskevkin: and friend and community.

Thanks God, Baruch Hashem. Ani modah al kol ma she’yesh li.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Grateful for everything you have, yeah, continue.

David Baskevkin: Yeah, I found that this connection with other that in the same situation, it started with my kids that they went to camps or or events with other widows from the war.

And my kids came back and they said, wow, we felt so good. We felt like normal. We felt like we can be ourselves. We can laugh, we can cry and feel good with our with ourself.

And each one of my kids felt the same way. It and it was very, um, amazing for me to understand the the power of be being together. And I started to get to know other almanot. It’s, we have, uh, in Israel more than 300, um, widows from this uh, war and more than 600, um, orphans.

Hadas Hershkovitz: And I find I need to pause for people to just understand that like, that there there’s like there’s a a demographic now. It’s like, it’s heartbreaking. You know, in America, we we talk a lot about, you know, how old were you during COVID? because it could change an educational trajectory and this is an order of magnitude that you we have a generation who sometimes young kids, young mothers, all different and it’s is it it’s this wound that is binding everyone.

David Baskevkin: It is, it’s crazy.

And you spoke about COVID and think about the generation in Israel. in Israel. They went through COVID, and after the COVID, the war started. And I think that even if you didn’t lose, lose,

Hadas Hershkovitz: Lose.

David Baskevkin: If you didn’t lose someone from your family, so you know someone from the neighborhood, you know someone. We grew up, you know, we knew some soldiers that was killed, were killed. But today the reality in Israel, that I think almost everyone knows someone. And some, sometimes in the community or in the city, few fallen soldier.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Can you tell me a little bit about how you connect to other families who have been through this? Is there a formal system? Is it like group work where you’re able to sit together? Tell me more about the special, just comfort or perspective that you’ve only been able to find not in your regular support group, but specifically people who have gone through this.

David Baskevkin: So we have WhatsApp group, and it’s so sad to see, you know, every few days another widow

Hadas Hershkovitz: Is added.

David Baskevkin: is added. And we have some groups.

We have, like a collective group and we have a group for women in my situation around my age with several kids. And you know, we have to get so many decisions, with the kids, with so many things during in our life. And I think that this group is many times helped to to get the right decision because we all, um, going through

Hadas Hershkovitz: This parenting process by yourself with young and

David Baskevkin: yeah, and sometimes if if I will ask for advice, someone that don’t understand exactly what I’m going through, even he’s very close to me, it won’t be the same feeling that I’m going to feel from other widows.

Hadas Hershkovitz: Can you give me an example or a question, like, you could be as broad or as specific as possible, something that like, this is the kind of thing, I need to discuss this with the group.

It doesn’t work with just stam, you know, I’m very close with my neighbors on both sides. We’re very, very close. We’re literally like family. So I know what it is to feel very, very close to your neighbors and community.