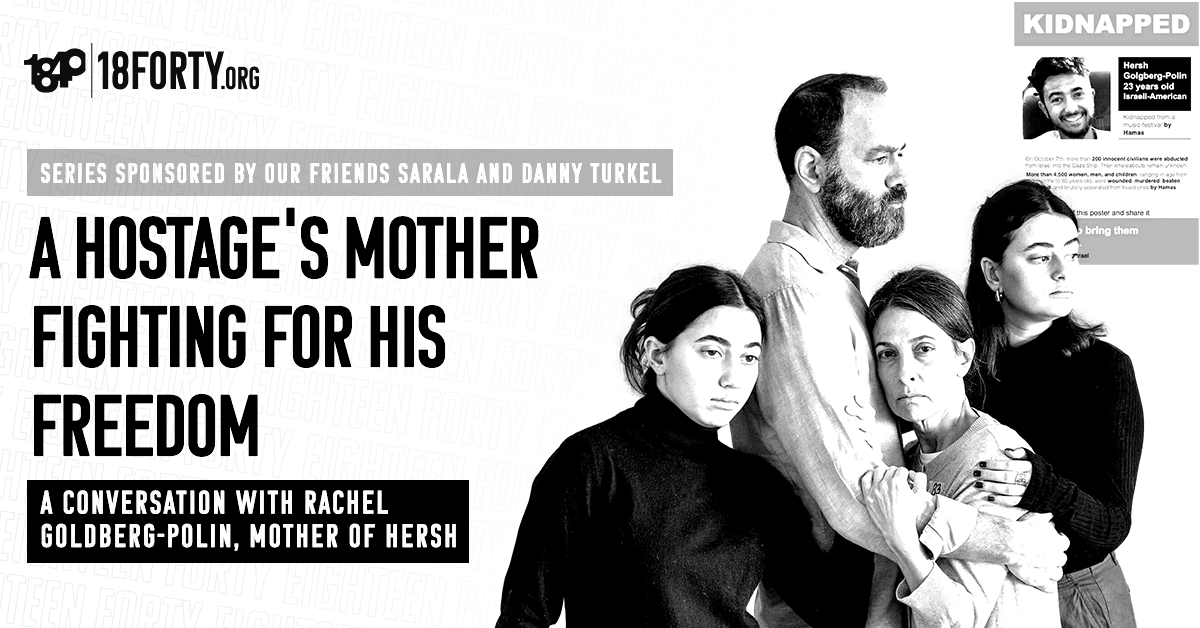

Rachel Goldberg-Polin: A Hostage’s Mother Fighting for His Freedom

In this special episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rachel Goldberg-Polin—whose son, Hersh, was kidnapped by Hamas and is still held hostage in Gaza—about heading into Passover with our loved ones still captive.

Summary

Our Intergenerational Divergence series is sponsored by our friends Sarala and Danny Turkel.

In this special episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rachel Goldberg-Polin—whose son, Hersh, was kidnapped by Hamas and is still held hostage in Gaza—about heading into Passover with our loved ones still captive.

Normally, Intergenerational Divergence feels like something of a choice. But now, Jewish families have been split apart by force. In this episode we discuss:

- How do we foster a continued connection to the members of our family who are missing?

- What difficult thoughts and questions will we bring to the Seder table this year?

- What does it mean to express hope via the Pesach Seder amid these bitter times?

We hope wholeheartedly that this conversation about missing our children at the time of Passover will be made irrelevant and the hostages will soon return home.

Interview begins at 7:17.

References:

“One Tiny Seed” by Rachel Goldberg-Polin

“To the Boys in the Room” by Rachel Goldberg-Polin

Sefer HaMenucha on Mishneh Torah, Leavened and Unleavened Bread 8:2

“A Prayer for Israel To Add to Your Pesach Seder” by Yosef Zvi Rimon

David Bashevkin:

Hi, friends. And welcome to the 18Forty Podcast, where each month, we explore different topic, balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host, David Bashevkin. And this month, we’re exploring Intergenerational Divergence. Thank you so much to our sponsors, Danny and Sarala Turkel. I’m so grateful for your support and friendship over all these years.This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big, juicy Jewish ideas. So, be sure to check out 18forty.org, where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly e-mails.Since we began the series of intergenerational divergence four years ago, we have explored so many different forms of divergence, whether it is spouses talking about their respective faith, whether it’s parents and children talking about the way they relate to religious life or communal life, whether it’s people from different communities talking about the way that their kids grow up, especially, vis-a-vis, the army as we’ve been discussing this year, the Israeli army, but it felt impossible to talk about intergenerational divergence this year since October 7th without talking to a parent, to a mother, who is dealing with perhaps the greatest divergence, which is the struggle of having a child who was kidnapped and held hostage currently by Hamas in Gaza.

It is a divergence not of practice or behavior or even community. It is the divergence of a part of a family being taken from you and being able to foster that sense of connection and advocacy even in their apparent absence to be able to forge that continued connection to those parts of our families that we cannot reach, we cannot speak to, we cannot call, even though we continue to hope and daven that they will be present this year at our Pesach Seder because the redemption of God can happen in a moment.

Yeshuas Hashem K’eref Ayin. And as we spoke about throughout this conversation today, which we’re privileged to host, with Rachel Goldberg, whose son, Hersh, continues to be held in captivity by Hamas. The refrain that we had throughout the episode is that it should be completely irrelevant by the time Pesach comes.

It should be unnecessary, unneeded and just cast to the waste bin of history, where instead, we’re able to rejoice and have the revealed redemption before our eyes where every single hostage, every single person who’s injured, every single soldier who’s still at war, returned home to be with their family, to connect with their family, and to be whole with their family.

Yet, without that revealed good before our eyes, it seems impossible to go into Pesach and discuss any form of divergence if we don’t speak about our hostages who continue to remain in captivity. And there is a special privilege of being able to speak to Rachel Goldberg, who has a unique expressive ability to be able to talk about the unfathomable and give it expression. But I wanted to begin with a poem that she said at the United Nations called One Tiny Seed.

And before we speak and hear more from Rachel about Hersh, about us, about Klal Yisrael, Knesset Yisrael, and the Jewish people, and what our mindset should be going into Pesach, going into Passover, a time of redemption, a time of unity, a time of freedom, knowing that someone is still in captivity, let’s first begin with a poem that she shared. It’s hard to believe or imagine almost four months ago. Here is Rachel Goldberg sharing her poem, One Tiny Seed.

Rachel Goldberg:

There is a lullaby that says, “Your mother will cry a thousand tears before you grow to be a man.” I have cried a million tears in the last 67 days. We all have. And I know that way over there, there’s another woman who looks just like me because we are all so very similar. And she has also been crying. All those tears are sea of tears. They all taste the same.

Can we take them, gather them up, remove the salt, and pour them over our desert of despair, and plant one tiny seed, a seed wrapped in fear, trauma, pain, war, and hope, and see what grows?

Could it be that this woman, so very like me, that she and I could be sitting together in 50 years laughing without teeth because we have drunk so much sweet tea together, and now we are so very old and our faces are creased, like worn-out brown paper bags, and our sons have their own grandchildren, and our sons have long lives, one of them without an arm, but who needs two arms anyway? Is it all a dream, a fantasy, a prophecy, one tiny seed?

David Bashevkin:

It’s an incredible expression of hope and how hope can sprout from the smallest possibility of hope. Yeshuas Hashem K’eref Ayin, the redemption of God, can come in an instant in a moment. And I’m really left speechless because, in many ways, Rachel is able to express the immutability of that hope, that hope that we could hold onto and take with us at all times and also the impossibility of the trauma and the crisis and the pain that she’s feeling and that we can hold onto in some small way, we can connect with in some small way.

And she got up at a rally just a few weeks ago. And there’s this image that was seared into my mind, that when she stepped to the podium, before she addressed the audience, she put her head down on the lectern, and she just said, “Today, I am too broken. The energy, the capacity, the creativity that’s sometimes required to give expression to unfathomable feelings is not always with us.”

But even when she put her head on that podium and said, “Today, I am just too broken,” being able to stand up and being able to say that, for me, is the continuation of that expression of that one tiny seed continuing to call to memory and to our attention all of the trauma and the difficulty and the continued need that we have as a people to pray for redemption, to advocate for redemption, to bring in some small way to one another, a glimmer, a tiny seed of redemption.

So, it is my greatest privilege to introduce our conversation with Rachel Goldberg. It really is a privilege. And just to give a little bit of background, every year, before Pesach, we do a series called Intergenerational Divergence, where we talk to parents and children who have very different identities.

And this year, given that we have parents like yourself who have children who are still in hostage, still in captivity, we wanted to have one conversation, the one that we’re going to release right before the Seder, to talk a little bit about that experience. And I’m very grateful that you’re taking the time to speak today.

Rachel Goldberg:

Well, thank you. I’m hoping that it will actually not be relevant.

David Bashevkin:

We are all hoping.

Rachel Goldberg:

I hope that if it’s before the Seder, that he’ll be home, and you’ll have to do a different intro.

David Bashevkin:

God willing, that is what we are all praying for. And maybe we could begin with a question about your son was taken in captivity by Hamas on October 7th. He’s no longer in your home. And you’re no longer able to communicate with him. A terrifying prospect.

And as one could imagine, any parent wants to hold on to the presence of their son being in their lives every single day. And my question that I’m asking is you’ve been very active politically to making sure that he is sent home. And I’m curious on almost a personal level, has the way that you have remained connected to him in your heart changed since October 7th?

Rachel Goldberg:

It has because it has grown so exponentially. And I’m so much more in touch with him on a minute-to-minute basis than I was before he was stolen. So, there’s really not a moment in the day where I’m not thinking about him or advocating for him or praying for him or talking with him. And I actually feel like my relationship with him is much deeper now because I have very poignant thoughts and communication with him. It’s just in a different way than before.

David Bashevkin:

Is there a specific place or object that you associate when you want to feel close with him, or is it solely something like an experience that you hold in your heart?

Rachel Goldberg:

I think there’s some of both. I walk a lot now. I have a circuit that I do at least once a day. Sometimes, today was twice a day on Shabbat. It’s usually three times a day. And I’m talking to him constantly while I’m on that circuit. And there’s different parts that I’m saying different things. We actually have a poster of him behind our front door that we used to take with us to certain gatherings. So, every morning when I’m davening, I look at him at certain points.

During Modim, I always look at him, and I wink because he’s one of the things that I’m grateful for. And then when I’m saying the prayer for the hostages, I go over, and I actually put my hands on his forehead, like I’m blessing him for Shabbat. And I say it. And then I’m looking into his eyes and saying it. And on Shabbat, I usually sit in front of the picture at some point, cross-legged, and talk right to him to remind him to stay strong. And I talk right into his eyes.

And I explain to him, “You have to stay strong mentally, spiritually, psychologically, emotionally, religiously, and physically. And you have to survive. And you have to use Deah Bina V’haskel. And you have to have Ru’aḥ Ha-Kodesh. And you have to figure out how to work with whoever’s there.” And I’m talking into his eyes, but that, I usually only do on Shabbat morning.

And everywhere in the house is there’s his makom kavua at the kitchen table, which I now sit in because I don’t like sitting and seeing him not sitting there. So, I now sit in his seat, and his place on the couch where he sits, and of course walking in his room. We feel him everywhere. So, he’s always here. He’s always with me.

David Bashevkin:

That is extraordinarily moving. And I’m wondering, you mentioned Modim, which is a prayer of thanks. And you said you give a little bit of a wink during Modim. And I’m wondering if you could expand, specifically during Modim, a mother who’s going through a time of such difficulty, you would think a prayer of gratitude would be the most distant or the hardest to connect to. And I’m curious if you would allow to expand upon a little bit about the significance of that wink that you give during Modim.

Rachel Goldberg:

The truth is all during davening, from when I start davening, there’s certain lines that I’m saying that are specifically related to Hersh throughout, and lines that we all take for granted. And I get hooked on them. And I repeat them. In barukh she’amar, I’m saying, “Podeh u’matzil, podeh u’matzil, podeh u’matzil, podeh u’matzil.” I’ll say it seven times or something. And then I’ll keep going.

And so, throughout all of daven, there’s certain parts that just really speak to me now. And in Shemoneh Esrei specifically, first of all, before I even start, when I’m saying, “Sur Israel pumah be’ezrat Israel,” and I’m saying it like that. My hands are up in the air. And, “ufdei chinumecha Yehudah v’Yisrael. Go’aleinu. Come on. Goel us.” And in the beginning, in the first three paragraphs, I look at him when I say, “Somech noflim.” And then I say, “Somech noflim,” with my hands.

And I say, “V’rofei cholim,” to my left arm where his arm was amputated. And I say, “U’matir asurim.” And I’m looking at him. And I’m saying, “U’matir asurim, u’matir asurim.” And each paragraph has something that I’m saying that is related to what we’re going through. So, by the time I’m getting to Modim, it’s like that’s very easy to me. That’s always been part that I do it in order in my family of who I knew first.

As I’m saying Modim, I picture Jon, and then I picture Hersh, and I look at him, his picture, because I daven at the dining room table. So, Hersh’s picture is I see it, and I wink. Then I picture my daughter, Leebie, and then I picture my daughter, Orly, and then I picture my parents, and then I picture my closest friend, and then I picture our team. And I’m trying to fit everybody in before I get to the end of Modim. And I am very grateful.

And I’m grateful that I can still be grateful. And that’s part of it, that I think that you can really lose yourself when you’re in trauma. You may have heard me talk about this, but everybody has experienced normative trauma. I shouldn’t say everybody because I think some people have been blessed and lucky in their lives. And maybe they haven’t. Normative trauma is you have an unexpected death in the family. Your partner comes home and says, “I want a divorce.”

And you didn’t see that coming out of anywhere. And you have a child that tells you something that is going to change the reality going forward. That’s normative trauma. That’s the metaphorical truck that you’re walking down the street, it hits you from behind, and knocks you completely off the road, and breaks every bone in your body, and you’re lying on your back. And when are you going to start to heal? That’s normative trauma.

And for different people, it’s a different amount of time that when are you going to sit up? When are you going to try to take that first step? When are you starting to integrate this new reality into your life? The problem with what the hostage families, what all of us are experiencing, is we’re experiencing what’s called, in psychology, ambiguous trauma. And the problem is that the truck is still on our chests.

And so, there is no, when do we sit up, when do we stand, when do we take our first step? The truck is still on us. All we’re trying to do is not move a molecule the wrong way that the truck crushes your rib cage and kills you. And so, it’s been so long that we’ve had this truck on our chest. And so, I’m grateful that somehow, with the truck on my chest, I can still recognize and appreciate that I have goodness in my life while I’m experiencing terror.

David Bashevkin:

It is incredibly moving the way that you read your own crisis into davening. It’s extraordinarily powerful and gives you really a window to what davening can be and should be. I want to speak a little bit about your poetry. You have composed, that I’ve seen, two incredibly moving poems. One, which was more recent, called To The Boys In The Room, which you said at a most recent rally. And you had an earlier poem that was called, I think, A Tiny Seed.

Rachel Goldberg:

One Tiny Seed.

David Bashevkin:

One Tiny Seed. Both of them are incredibly moving. When did you discover this ability and capacity to express the pain and the trauma that you are very much still unfolding in your life? When did you discover this capacity to express it through poetry?

Rachel Goldberg:

I actually have written… There’s other poems that I’ve read at different gatherings early on. One was Day 31, I think, that I read. It was a combination of talking about Yosef and Yaakov, and Yaakov not accepting, even though he saw the coat with the blood. He knew somewhere, he’s coming home, or I’m coming to him.

And then at the end of that, I talked about shir hamma’alot beshuv adoshem et-shivat Zion, and that we will be laughing so hard when these hostages, they’re going to come home, and we’re going to laugh so hard, our laughter will fall all over the floor. And that was something that I wrote. I think it was sometime in the 30s. There have been several. And it was early on.

And it was when I couldn’t sleep. And I would just write because the truth is I’m not a very good writer, but I feel like I can express myself. So, it looks like poetry. I think it’s actually just the way that I can get out. Other people can articulate themselves in a very polished way.

I’ve never been great at that, but I was always able to explain myself, I think. And so, it is this… I’m not even sure if it is poetry. I always say it’s poetry because I think that’s more forgiving than saying, “Here, I’ve written something.” So, when you call something a poem, I think you get a pass, and you can present an idea that’s not fully baked, and the world is more forgiving because it’s poetry.

David Bashevkin:

There is a visceralness, I think. I would describe it as there’s something very visceral and very raw about the way specifically you expressed yourself in your poetry. And I’m sorry I didn’t see that poem about the coat of Yosef. It happens to be at our Pesach Seder. My father, every year, says the same d’var Torah. And that is that the origin of the term Karpas comes from that dipping of the coat.

When Rashi talks about what was happening when they dipped that coat, he uses the term Karpas. And that is an imagery at the Seder that when we dip that vegetable into saltwater, to have something so broken and traumatic, but to be able to look at it and say, “I’m not going to believe it. I’m not believing this is the end. There is still hope, and there is still freedom that is going to emerge from this story,” is really truly incredible. I would love for you read that.

Rachel Goldberg:

Okay. So, it’s called Dreamers. It says in the Gemara, “All of Israel is responsible for one another,” but I think it’s a mistake. All humans are responsible for one another. I don’t think it matters anymore what brand we are, what age, what religion, what class, what shape, what size, what worldview, what texture. All that matters is if you have a soul and breath inside.

At the end of the day, there are 240 souls buried alive, deep below the ground, but they are breathing. And here I wait, like Jacob being told, “Here is Joseph’s coat. See, it’s all bloody,” but just you wait, ani ma’amina be’emuná shelemá. One day, we will see them again. We will all fall on all of their necks, and weep when we see their faces, and see they are still alive. When the captives return to Zion, we will be like dreamers, and our mouths will spill out with laughter all over the floor.

David Bashevkin:

The imagery in that with Yosef and Yaakov and the reunion later on is beyond moving, which really brings me to the moment we’re in. And this is a difficult question to ask. We are all hoping that this entire conversation between you and I is woefully irrelevant. We just cast it aside. And we are now focused on the actual revealed good and redemption that we have in front of us. But there is a possibility that we may not be able to experience that.

And we will be having a Passover this year that is different than all other nights and all other darknesses that we have felt when celebrating Pesach. And I wanted to know from you, number one, at your own personal Seder, is there anything that you’re specifically going to be doing different.

And more so, for others who want to connect to your unimaginable, ungraspable pain, are there any recommendations or thoughts that you would want to see that would bring some measure of comfort for others to be doing at their Seder to keep the idea that Hersh, still alive, still breathing, but not with us at that Seder? How would you want Hersh to be preserved at Passover Seder?

Rachel Goldberg:

So, I’ll answer the first part first, which is we’re having Seder with our closest friends. That’s one family and Jon’s first cousin, his family, which we’ve done the last four or five years since COVID because we used to go back to be with our extended family. So, since 2020, we’ve been here. And they actually checked in with us on Shabbat, this past Shabbat, to say, “Obviously, we have to do things differently. What exactly would you want us to do?”

And they even offered also that we don’t have to have both of those families. It could be just one of those families if it’s just too much. And every group does Seder different. And this is a family that really goes to town with Seder. You open the door, and they’re dressed like pharaoh, and they’re dressed like Egyptians. And they do the whole Seder on the floor. They have mattresses all over the floor and pillows everywhere.

And it’s a very Sparti Seder and there’s a lot of jokes and a lot of fun. And we just said, “That, we can’t do this here.” This is the Chag ha’Cherut, and we’re the embodiment of slavery. Our souls are bound up with Hersh and with those other 132 souls. We are bound up with them. So, we are completely held captive. And it will be very artificial. But sometimes, in life in Judaism, you walk through things artificially. That’s just the way you do it.

And there are times I’ll say, when I’m davening, before I even start, I look up, and I say, “This is not going to be good.” And I’m warning God, “I’m going to daven today,” because I daven every day, but this is not going to be good for you, and it’s not going to be good for me. And I walk through it. And I say the words. And I’m like a robot. And there are times, in Judaism, we had a good friend years ago who, Erev Pesach, had to bury her husband that morning.

And she had three little kids. And it was a complete tragedy. And she had to go to Seder that night. And I’m sure she was a robot, but she did it. And I said, “I wish somebody could put me in an induced coma, Erev Pesach, and just wake me after Isru Chag because it will be torment if that’s the case, if he’s not home by then.”

And I said to them, “I don’t know what to prescribe and what to say. I think let’s use good judgment. And when I can’t do it, if I get to a point, I’ll go in the other room, and I’ll lay down, and I’ll sleep over at your house in the other room.” Years ago, it’s interesting, when I was pregnant with my daughter Orly, who’s now 18, I was horribly, horribly sick in that pregnancy. And I was fed intravenously because I was so sick I couldn’t keep anything down.

And we were supposed to go to Israel for Pesach. We were living in Richmond, Virginia. And I ended up saying to Jon, “You go. Take Hersh.” I can’t remember if he took Libbie, or if Leebie was home and we had a babysitter. I can’t remember. It was such a traumatic period, but I spoke to the rav of the community because there was no way I could go to Seder. And I wasn’t having Seder.

And he pared it down for me, “What is the bare minimum halachically that you have to do to have done a Seder?” And the part that stands out to me that I remember specifically is he said, “You must ask yourself the four questions out loud.” I do remember that. And I did two Seders by myself with my intravenous thing and taking the bare minimum sips of grape juice that I had to take. And I did a bare minimum Seder, but I walked through that Seder.

For this year, I was asked to write the introduction to Haggadah that they were publishing, and I wrote. This year, there’s so many more than four questions, but certainly, the fifth question is, why isn’t everybody here? Someone asked a couple weeks ago, “What would you like us to do for Pesach?” Thank God we have this wonderful Dahlia. She’s like a daughter to me. She is our social media guru.

And she said, “People are starting to say, ‘What should we do?’ Do you want us to put something on the Seder plate? Do you want us to have a chair?” And we were upset a couple weeks ago. Jon and I said, “Enough with the empty chairs. Let’s fill the chairs.” Every week, people are sending us pictures of their empty chairs, which we really appreciated. And on the other hand, it’s like sticking a finger in my eye.

Every week, I had someone, I felt bad for her because she was so sweet and kind. She’s an acquaintance really. And every week, she would write to me, Erev Shabbos, a few hours before Shabbos, and she’d say, “I cannot believe it’s the 17th Shabbat, and you don’t have… I can’t believe it’s the 18th Shabbat, and you don’t have…” I finally wrote to her a few weeks ago. I said, “It is not at all helpful to me when you do that.” And I felt terrible.

She said, “I’m so happy you told me that.” It’s like when people say, “How are you?” And I know they’re meaning it in a good way, but, “I don’t know. I’m in the middle of being raped. How do you think I am? Don’t ask me that.” I feel like it’s so inappropriate. It’s like walking into chuppah and saying, “What’s new? Have some sehul.” So, Dahlia said, “People are asking, ‘What should we do?’ People want to do something.” And I’m so in denial.

I said, “I don’t want to think about it. I don’t want to think what should you put on your Seder plate because my life is such a train wreck,” but on the other hand, I don’t want it to go unrecognized. And I think it is really a teachable moment. And I think this is a moment in Jewish history that is unprecedented in many ways. And I think it is a moment that we need to figure it out in these next few days. If these people aren’t home, what are we going to do?

And I haven’t given it thought because it’s so painful to think about, that it’s hard to think about. And now, what will we do to remember that and to publicize that? But I do have to come up with an answer for that because it’s a very fair question, and it’s actually a very kind question, and it’s a very generous question and thoughtful. And I just have been in denial, but I have to come up with something. Do you have any ideas?

David Bashevkin:

Far be it from me to make a suggestion, but what you began with, there is a tragic irony that we’re looking for an answer. And Pesach is all about questions. And I found it extraordinarily moving to go into this Seder and say, “We don’t have the answer, but I do know a question that we should be thinking about really formally within the Seder. Why isn’t everyone here?” And to sit with a question without an answer, in a way, feels appropriate.

It feels, to me at least, because so many are struggling, we want to be a part of it. We want to connect. We want to bring this message out. And it’s hard sometimes to find the right words and the right language and the right answers, so to speak, that are going to get us there, but your initial instinct that you suggested of recognizing that we may not have all of the answers, if that possibility does arise, the ultimate answer, which is having every single hostage, having Hersh home.

If we don’t have the ultimate answer, then to sit with another question, to me at least, feels like what Pesach is all about, what the question of an unfolding redemption that is not all the way there is all about. And your graciousness and your educational capacity in teaching me, David Bashevkin, giving us a little bit more language and a window to understand the unimaginable to touch and just connect to something that we know we will never fully connect with is what questions are all about.

And I just found that opening incredibly moving. I’m not giving you an answer, but I’m letting you know that question resonated. And I think that’s what so many of us who are not all the way there are trying our best to be there. And I know that we are, to different degrees, falling short.

To sit with a question, there’s a holiness in that. So, thank you. My final question, it is the time of redemption, it is the time of hope, and I’m wondering if you could share a little bit about what you hold onto when you need hope and need strength in these trying, incredibly difficult last six months.

Rachel Goldberg:

I really hold on to the knowledge that he’s coming home. I know he’s coming home. I just don’t know when. And I don’t know how. I do know how. I know it’s going to come from Hashem, but I don’t know what tricks are up Hashem’s sleeve. I don’t know. None of us know. We say we don’t know who the vehicle will be or who is the kli, who is the vessel, and what stone has to be overturned? And I don’t know the answer to that.

I know that I’ve met so many people in these last six months who have taught me so many different ideas that have helped me through. And it’s interesting and ironic that the one that’s really been helpful, because Jon and I have been in constant motion, constant, constant motion. We never rest. We never, never rest.

And I actually now appreciate, I used to criticize people like that, I thought they were running away from something, people who just constantly have to be doing something. I always think, “What are you running away from when you’re like that?” And now, I’m like that. And it’s because I’m running away from feeling terrified at all times.

And so, when you’re in motion and when you have a goal and you have a mission, it’s also good because it distracts you from being in this elegant, precise misery that we are constantly in. And so, we met this reverend who came to our home a few months ago.

And he just shared, as he was leaving, a saying by Saint Augustine because he was very taken with how, to him, he felt that we were very devout, that we pray a few times a day, and that we’re constantly saying Tehillim. And he said, “You have to pray like it all depends on God. And you have to work like it all depends on you.”

And that’s what we have been doing when we’re davening, and we’re throwing our arms up in the air, and when we’re saying Tehillim, and when we’re doing all these mitzvot in the merit that Hersh and the other hostages should come home safe, kehelathah’in, immediately. But we’re also running everywhere. Anyone who we think can be at all helpful, or we’re not even sure if they could be at all helpful, but we’ll go. And people come to us with crazy ideas. And we go.

Can you talk to this person? Go. Will you talk at the UN? Go. Will you talk to the president? Go. Will you talk to the Pope? Okay. And who knows? I think that, I don’t know that it’s going to come from some fancy, diplomatic, well-known source, but I hold on to the idea that I have to do every single possible thing. So, I know that I did every single possible thing. And I keep picturing Hersh at his wedding.

He’s not dating anyone as far as I know, unless he met a nice girl in Gaza, which is possible because there are a lot of nice girls there, but I picture him at his wedding. I see the picture behind you on your shelf. I picture me holding his baby. And these are things that you have to manifest and create hope, hope is mandatory, or I think that the weight of the truck would just crush me.

David Bashevkin:

I cannot thank you enough for sharing. This is just a few days before Pesach. And I know my Tefillos, my prayers, my thoughts are with you and towards the one who can change everything, k’eref ayin, in just a moment. Yet, we will continue to work each of us as if it all depends on us.

Incredibly moving. And I am just so grateful for you taking the time out, very precious time, to share your story, your message, your prayerful ideas with us today. So, thank you so much. It was truly a privilege to speak with you.

Rachel Goldberg:

Well, it’s a privilege to speak with you. And I feel honored that you thought to approach us and that you care about this topic and Hersh and the story of all the hostages. And God willing, in a couple of days, you’ll have to call back and say-

David Bashevkin:

Amen.

Rachel Goldberg:

… “Can I interview Hersh because we have to tweak this a little bit so that it presents better now that he’s home?”

David Bashevkin:

Amen.

Rachel Goldberg:

Amen.

David Bashevkin:

It was during my conversation with Rachel that I really developed new insight that I never had before for this custom at the Pesach Seder that we call Karpas, when we dip a vegetable into saltwater. It was always a strange custom. And it seems that the reason why we do it, the Talmud says, is just so that the children should ask. So, we have this custom.

And it is later commentaries that find incredible imagery in why we specifically, of all the things that we could do to perk our children’s attention, dipping a vegetable into saltwater. I don’t know if that’s the number one thing that would catch my child’s attention. And one of the later commentators, specifically Rabbenu Manoach, actually explains that the reason why we dip specifically a vegetable into saltwater. Why are we doing this act of dipping?

It is to remember the act of dipping that the brothers of Yosef dipped his garment into blood to convince Yaakov that Yosef was already gone. Rabbenu Manoach says this on the Rambam. You can look it up in Hilchot Chametz U’Matzah in the eighth chapter in the second Halakha.

And my father, as I mentioned in the conversation, at every single Pesach Seder, quotes from Rashi on Chumash, which is really, really remarkable, talking about Yaakov’s love for his child, the Yisrael Ahav es-Yosef. And Yisrael, also Yaakov, known as Yaakov, loved his son Yosef of all of his children. And he made him this coat called a ketonet passim. Rashi says the word passim is a strange term.

And Rashi quotes … It’s this overcoat … The word Karpas is right there, Rashi says, quoting from a verse in Megillat Esther, Karpas. Rashi connects to ketonet passim. And that I always knew. And we said that at every single Seder that the dipping of the vegetable is to re-enact, and remind our imagination, that act of the brothers of dipping the coat into blood to convince Yaakov that Yosef was already gone.

But after speaking to Rachel, I’m just so moved because what she said is that Yaakov didn’t believe it. He continued to hope. He wouldn’t take anybody’s nehama as if he had passed. He says, “I am continuing to hope my child is still alive.” And that gave me an insight, I think, for the significance of Karpas, that it’s actually when we dip that vegetable into saltwater, we make a bracha on the vegetable and make a borei pri ha’adamah.

We’re supposed to actually have in mind that the bracha that we make is supposed to also serve as a bracha for the maror, that bitter herb that we have later in the meal. So, whatever you use for Karpas, whether it’s celery or potatoes or whatever you have, the bracha, the borei pri ha’adamah that we make on that actually also exempts the need for a bracha that we were supposed to make later on the maror.

And after speaking to Rachel, I think there’s such incredible imagery that what the Karpas is really a reminder on was Yaakov, after being presented with Yosef’s coat dipped in blood, where any normal person, any normal parent, would say, “I’ve lost all hope. It’s the end. The story is finished. I’ve lost my child,” and Yaakov, instead, continues to hope.

He says, “I’m not letting go yet. This is not enough evidence. I am continuing to daven. And I’m continuing to plead before the Almighty that my son, Yosef, returns home.” And he does return home. And this idea said by Rachel of holding onto hope in that real tangible way and saying, “I’m going to see Hersh again. This is not the end of the story,” that our Karpas is what transforms our maror.

Karpas being the representation of grasping on and not letting go of hope no matter the circumstances, no matter how dark it may seem. And it’s the very bracha that we make on Karpas, that borei pri ha’adamah that we have in mind for all of the maror in our lives.

And this year, the Jewish people have had an incredible amount of maror, an incredible amount of bitterness, families who have buried children, families who have spent far too long in hospitals, individuals who have been subject to an anti-Semitism and a Jew hatred that we thought we forgot a century ago. And here we are at the Pesach Seder. And we’re reenacting that hopefulness of Yaakov, that hopefulness of a parent, that hopefulness of Rachel Goldberg.

And we’re saying that when I put this Karpas in my mouth, I’m refusing to let go of that hope. I’m continuing to daven. And I’m actually having in mind all of the maror that we’ve experienced, all of the pain, all of the endings of those stories. So long as I hold onto that hope embodied by Karpas, I can infuse hopefulness and meaning even in our most bitter stories and most bitter endings.

And it is that unique poetry that Rachel has, that haunting question that she’ll be thinking about, that I’ll be thinking about, that we’ll be thinking about at the Seder of all those who are still missing, all those who are not yet home, all those who haven’t completely healed, that can transform our Seder, that this year’s Pesach will not be like any other Pesach we have celebrated in our lifetimes. And I want to end with one prayer.

I had the opportunity to speak with a previous guest, Yosef Zvi Rimon, who has been a source of guidance and comfort since October 7th. And I asked him the same question that I asked Rachel Goldberg, how should our Pesach Seder be different this year? And he sent me something that he wrote. If you’ll allow me, I’d like to read it. It is in Hebrew, but of course, I will translate.

And he sent to me a tefillah on the situation that the Jewish people are in that we should say before we recite Vehi Sheamda. And this is the prayer. We give thanks before you, our God and the God of our forefathers, that we’ve merited to live in the generation of redemption, and that we have merited to see the building of our home state, the state of Israel, that we’ve merited to see the strength of our people, the resilience of our people, and that we’ve merited to see miracles and wonders that have been promised to us through your servants, the prophets, so many millennia go.

It should be your will, our God, and the God of our forefathers. You should give continued strength to the Israeli defense forces and all those who contribute to our security, who stand guard in our land and the cities of the divine, the cities of our homeland.

You should strike down any enemy who comes before us, to protect all of our soldiers from any suffering or pain or difficulty, and give them blessing and success in all their endeavors, to return all of the hostages and all those in captivity.

They should be healthy both physically and emotionally, to give an immediate recovery and heavenly insistence to all those who’ve been injured, and to exact revenge for all of the spilled blood of your servants, to continue to redeem each of our souls, in the same way that you protected us from all those who have come to eradicate and destroy the Jewish people.

Give wisdom to our leaders and plant unity and togetherness and love among all of the Jewish people. And more than anything else, what moved me so much about this tefillah and what Rachel Goldberg said is this beginning that it begins with Modim. It begins with gratitude.

And what Rachel Goldberg said, that wink that she gives during Modim, that wink, that ability to find some tiny seed of hope, that hope of Karpas, that even when it seems bleak, when it seems hopeless, when it seems over, when it seems finished, that our Pesach Seder should give us that tiny seed of hope, to have that wink during Modim, and that through our ceaseless hopefulness, through all of our continued prayers, through the example of all of the mothers who continue to hold on to all those who are held captive, all of the families who continue to hold on even through all of this ambiguous trauma that they have been living with, and to be able to hold onto that hope of Karpas and saying, “The story is not yet over,” and to think and inject and infuse that hopefulness in all of the Maror that we have experienced over all of these months.

I’ll just add one thing from my own personal family custom. My father had a patient who reached out before the Pesach Seder. And he said a custom that I don’t know where it comes from, but we still do it at our Pesach Seder … when the Pesach Seder recalls the Jewish people crying out. He asked my father and our family to say a prayer because that is a special Eis Ratzon, a meritous time for prayers.

And that maybe this year, whether it’s the prayer of Rav Rimon, whether it’s the question that we ask of Hakadosh Baruch Hu and of ourselves to continue to work and wondering where the hostage is. Why is anybody still not yet home? Why is there one chair left empty at any Seder?

Or whether it’s an added prayer … that before we talk about the screams of the Jewish people in slavery, we add our own screams and cry out to Hakadosh Baruch Hu and to God for what we are missing. However you decide to transform your Seder, it should be a transformative Seder. It should be a Seder that is prayerful because this night is different than all other nights of the Seder that we’ve experienced in our lifetime.

And bridging that world of hope to the world of bitterness, wishing each and every single one of you in uplifting Passover, a chag kasher v’sameach, that we should see the revealed good in our times. And we should each merit to say a full Modim with winks and smiles with our loved ones as we greet the complete revelation, the Geula Shleima, before our eyes. A happy and uplifting Passover to each and every one of you.

So, thank you so much for listening. And thank you again to our series sponsors, Danny and Sarala Turkel. I’m so grateful for your friendship and sponsorship. This episode, like so many of our episodes, was edited by our dearest friend, Denah Emerson. If you enjoyed this episode or any of our episodes, please subscribe, rate, review, tell your friends about it.

You could also donate, of course, at 18forty.org/donate. That’s 1-8-F-O-R-T-Y.org/donate. It really helps us reach new listeners and continue putting out great content. You can also leave us a voicemail with feedback or questions that we may play in a future episode. That number is (516) 519-3308. Once again, that number is (516) 519-3308.

If you’d like to learn more about this topic or some of the other great ones we’ve covered in the past, be sure to check out 18forty.org. That’s the number 18, followed by the word, forty, F-O-R-T-Y.org, 18forty.org, where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails. Thank you so much for listening. And stay curious, my friends.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Julia Senkfor & Cameron Berg: Does AI Have an Antisemitism Problem?

How can our generation understanding mysticism, philosophy, and suffering in today’s chaotic world?

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Yehuda Geberer: What’s the History of the American Yeshiva World?

We speak with Yehuda Geberer about the history of the yeshiva world.

podcast

Aaron Kotler: Inside the Lakewood Yeshiva

We speak with Rabbi Aaron Kotler about the beginnings of the American yeshiva world.

podcast

What Garry Shandling’s Jewish Comedy Teaches About Purim

David Bashevkin speaks about the late, great comedian Garry Shalndling in honor of his 10th yahrzeit, which is this Purim.

podcast

The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

podcast

Micah Goodman: ‘I don’t want Gaza to become our Vietnam’

Micah Goodman doesn’t think Palestinian-Israeli peace will happen within his lifetime. But he’s still a hopeful person.

podcast

Alex Edelman: Taking Comedy Seriously: Purim

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David is joined by comedian Alex Edelman for a special Purim discussion exploring the place of humor and levity in a world that often demands our solemnity.

podcast

On Loss: A Spouse

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Josh Grajower – rabbi and educator – about the loss of his wife, as well as the loss that Tisha B’Av represents for the Jewish People.

podcast

Pawel Maciejko: Sabbateanism and the Roots of Secular Judaism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to historian and professor Pawel Maciejko about the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, Sabbateanism, and the roots of Jewish secularism.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

David Aaron: ‘I believe that the Divine is existence and infinitely more’

Rabbi David Aaron joins us to discuss ease, humanity, and the difference between men and women.

podcast

When A Child Intermarries

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to a son who almost intermarried, the mother of a daughter who married a non-Jew, and Huvi and Brian, a couple whose intermarriage turned into a Jewish marriage—about intergenerational divergence in the context of intermarriage.

podcast

Modi Rosenfeld: A Serious Conversation About Comedy

In this special Purim episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we bring you a recording from our live event with the comedian Modi, for our annual discussion on humor.

podcast

Netta Barak-Corren: ‘I hope that Gaza will see a day when it is no longer ruled by Hamas’

Israel is facing several existential crises—at least three, by Netta Barak-Corren’s account.

podcast

Anshel Pfeffer: ‘The idea that you’ll obliterate Hamas is as realistic as wanting to obliterate Chabad’

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu did not surprise Anshel Pfeffer over the last 17 months of war—and that’s the most disappointing part.

podcast

Michael Oren: ‘We are living in biblical times’

Israel is a heroic country, Michael Oren believes—but he concedes that it is a flawed heroic country.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Yakov Danishefsky: Religion and Mental Health: God and Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Yakov Danishefsky—a rabbi, author and licensed social worker—about our relationships and our mental health.44

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

Leah Forster: Of Comedy and Community

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David sits down with Leah Forster, a world-famous ex-Hasidic comedian, to talk about how her journey has affected her comedy.

podcast

Lizzy Savetsky: Becoming a Jewish Influencer and Israel Advocate

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Lizzy Savetsky, who went from a career in singing and fashion to being a Jewish activist and influencer, about her work advocating for Israel online.

podcast

Ken Brodkin: A Shul Becomes Orthodox

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Ken Brodkin, rabbi of New Jersey’s Congregation B’nai Israel, about how he helped turn it into “the Orthodox synagogue for all Jews.”

podcast

Shulem Deen: Faith, Without Faith

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David discusses with special guest and former member of the Ultra-Orthodox community, Shulem Deen, the struggle and importance of balancing one’s individual needs with those of the community.

Recommended Articles

Essays

3 Arguments for God’s Existence

Perhaps the most fundamental question any religious believer can ask is: “Does God exist?” It’s time we find good answers.

Essays

Ki Tisa: The Limits of Seeing God’s Face

We spend our lives searching for clarity. Parshat Ki Tisa suggests that the most meaningful encounters may happen precisely where clarity ends.

Essays

What is the Megillah’s Message for Jews of the Diaspora?

For some, Purim is the triumph of exile transformed. For others, it warns that exile can never replace the Land of Israel.

Essays

The American Yeshiva World: A Reading Guide

A guide to the essential books that tell the story—past and present—of the American yeshiva world and its inner life.

Essays

A Jew in the King’s Court: Dual Loyalty in the Book of Esther

The Book of Esther suggests that diaspora is not merely a temporary or anomalous state but an integral part of Jewish history…

Essays

(What) Do Jews Believe About the Afterlife?

Christianity’s focus on the afterlife historically discouraged Jews from discussing it—but Jews very much believe in it.

Essays

Why We Need to Live With Radical Laughter This Purim

Brother Jorge asks: Can we laugh at God? We might answer: We can laugh with God.

Essays

How Orthodox Jews Are Sharing Torah Knowledge Across Denominations

Two programs are already bridging the Orthodox and non-Orthodox divide through the timeless tradition of chavruta learning.

Essays

The Siddur Has a Lot of Prayers. Where Did They Come From?

Between early prayer books, kabbalistic additions, and the printing press, the siddur we have today is filled with prayers from across history.

Essays

Judith Herman Is Giving Voice to Survivors

Dr. Judith Herman has spent her career helping those who are going through trauma, and has provided far-reaching insight into the field.

Essays

Towards the Derech: How Does a Reform Jew Return?

The “way” of myself and other formerly Reform Jews is unclear, but our desire for spiritual growth is sincere.

Essays

How Jewish Communities Can Help Couples Going Through Divorce

Divorce often upends emotional and financial stability. A Jewish organization in Los Angeles offers a better way forward.

Essays

What Are the Origins of the Oral Torah?

A bedrock principle of Orthodox Judaism is that we received not only the Written Torah at Sinai but also the oral one—does…

Essays

What Haredim Can Teach Us About Getting Off Our Smartphones

Kosher phones make calls and send texts. No Instagram, no TikTok, and no distractions. Maybe it’s time the world embraces them.

Essays

A Brief History of Jewish Mysticism

To talk about the history of Jewish mysticism is in many ways to talk about the history of the mystical community.

Essays

A Letter to Children Estranged From Their Parents

Children cannot truly avoid the consequences of estrangement. Their parents’ shadow will always follow.

Essays

What the 18Forty Team is Reading This Adar

Identity, desire, women in fiction, and more: What we’re reading before Purim.

Essays

The Hardal Community Explained: Torah, Am Yisrael, and Redemption

Religious Zionism is a spectrum—and I would place my Hardal community on the right of that spectrum.

Essays

Is Judaism Fundamentally Zionist?

God promised the Land of Israel to the Jewish People, so why are some rabbis anti-Zionists?

Essays

Divinity and Humanity: What the Jewish Sages Thought About the Oral Torah

Our Sages compiled tractates on the laws of blessings, Pesach, purity, and so much more. What did they have to say about…

Essays

What Jewish Denominations Mean to Me

Jewish denominational labels are only 200-year-old labels. So why do they govern so much of modern Jewish life?

Essays

How Archaeology Rewrote the History of Tefillin

From verses in Parshat Bo to desert caves, tefillin emerge as one of Judaism’s earliest embodied practices.

Essays

How Did Modernity Change Jewish Prayer?

Modernity brought sweeping changes to the Jewish community—and prayer was not immune, not in Reform, Reconstructionist, Conservative, or even Orthodox communities.

Essays

Benny Morris Has Thoughts on Israel, the War, and Our Future

We interviewed this leading Israeli historian on the critical questions on Israel today—and he had what to say.

Recommended Videos

videos

Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin: How Torah Gives Us Faith and Hope

In this special Simchas Torah episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Rachel Goldberg-Polin and Jon Polin—parents of murdered hostage Hersh…

videos

A Vulnerable Conversation About Shame, Selfhood, & Authenticity with Shais Taub & David Bashevkin

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Shais Taub, the rabbi behind the organization SoulWords, about shame, selfhood, and…

videos

The Hasidic Rebbe Who Left it All — And Then Returned

Why did this Hasidic Rebbe move from Poland to Israel, only to change his name, leave religion, and disappear to Los Angeles?

videos

An Orthodox Rabbi Interviews a Reform Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue, about denominations…

videos

Torah Study and ChatGPT: How Should Jewish Education Respond to AI?

On this 18Forty panel, we speak with Alex Jakubowski of Lightning Studios, Sara Wolkenfeld of Sefaria, and Ari Lamm of BZ Media…

videos

A Reform Rabbi Interviews an Orthodox Rabbi | Dovid Bashevkin & Diana Fersko (Part 2)

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin answers questions from Diana Fersko, senior rabbi of the Village Temple Reform synagogue,…

videos

Is Modern Orthodox kiruv the way forward for American Jews? | Dovid Bashevkin & Mark Wildes

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Mark Wildes, founder and director of Manhattan Jewish Experience, about Modern Orthodox…

videos

Mysticism

In a disenchanted world, we can turn to mysticism to find enchantment, to remember that there is something more under the surface…

videos

Joey Rosenfeld: What Does Jewish Mysticism Say About This Moment?

We speak with Joey Rosenfeld about how our generation can understand suffering.

videos

Why Naftuli Moster Left Haredi Education Activism

We speak with Naftuli Moster about how and why he changed his understanding of the values imparted by Judaism.

videos

What are Israel’s Greatest Success and Mistake in the Gaza War?

What has been Israel’s greatest success and greatest mistake?

videos

Steven Gotlib & Eli Rubin: What Does It Mean To Be Human?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast—recorded at the 18Forty X ASFoundation AI Summit—we speak with Rabbi Eli Rubin and Rabbi Steven…

videos

Moshe Weinberger: ‘The Jewish People are God’s shofar’

In order to study Kabbalah, argues Rav Moshe Weinberger, one must approach it with humility.