The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism

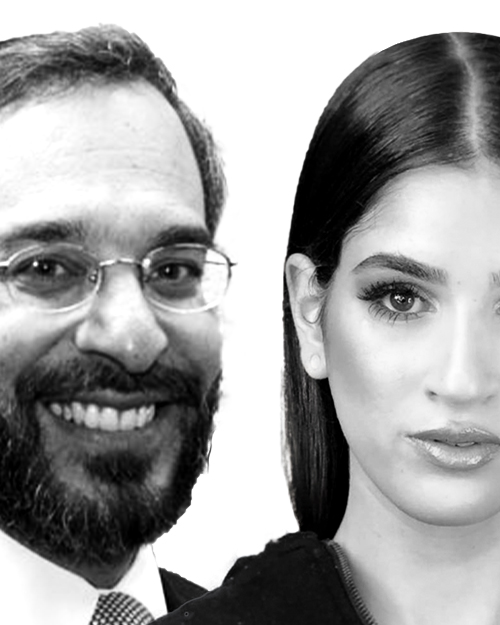

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

Summary

Our Intergenerational Divergence series is sponsored by our friends Sarala and Danny Turkel.

This episode is sponsored by an anonymous friend who supports our mission.

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

- Why did Aharon initially choose to stay anonymous to protect his parents from public pushback?

- How can we identify positive qualities in people we viscerally disagree with?

- Do differences over Israel and Zionism need to tear families apart?

Interview begins at 19:08.

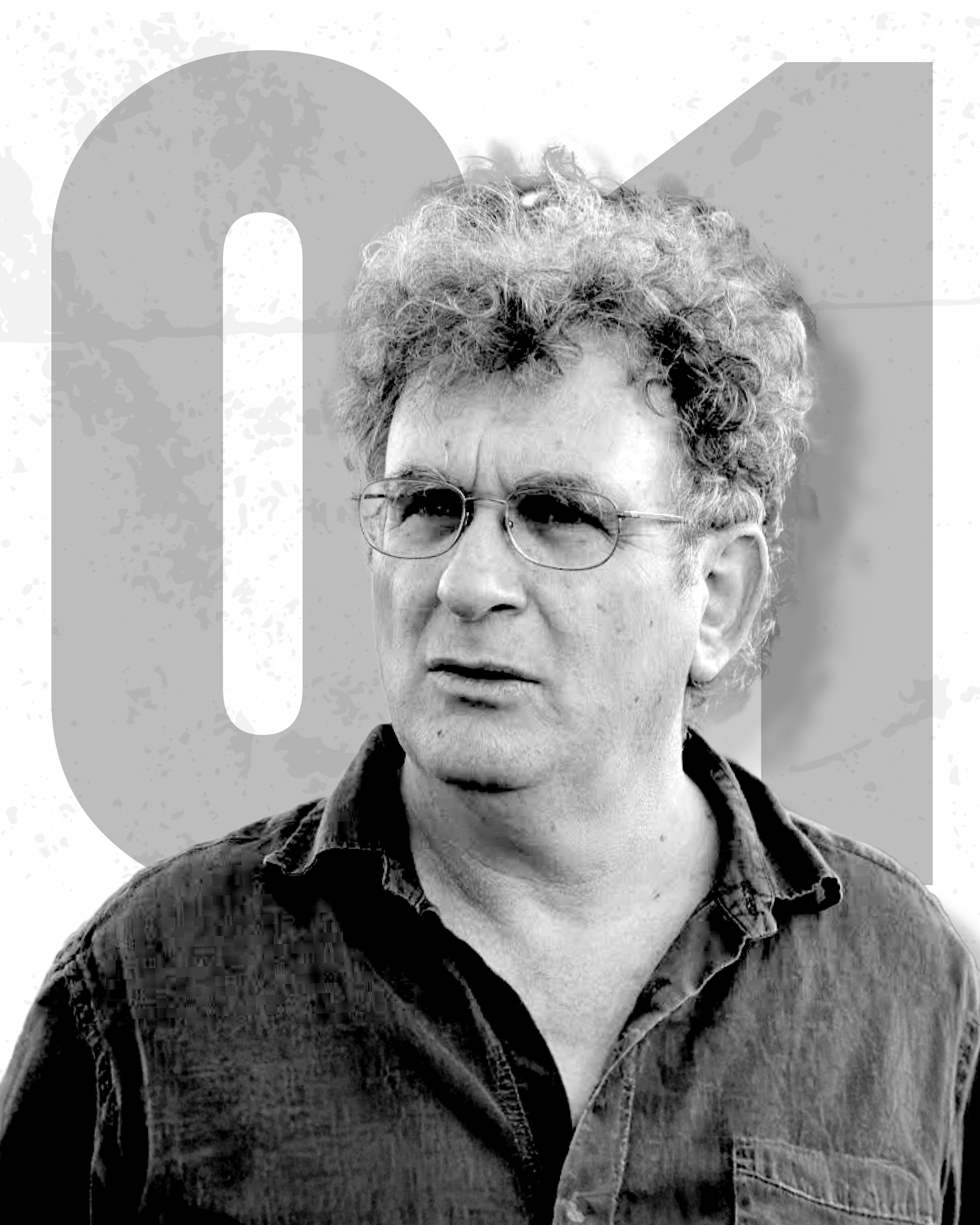

Rabbi Judah Dardik is an Assistant Dean and full-time Ramm at Yeshivat Orayta in the Old City of Jerusalem, where he teaches and oversees student welfare. He is also the Dean of the Orayta Center for Jewish Leadership and Engagement. Before making Aliyah, he completed 13 years as the spiritual and community leader of Beth Jacob Congregation, in Oakland, California.

For more 18Forty:

NEWSLETTER: 18forty.org/join

CALL: (212) 582-1840

EMAIL: info@18forty.org

WEBSITE: 18forty.org

IG: @18forty

X: @18_forty

Transcripts are produced by Sofer.ai and lightly edited—please excuse any imperfections.

David Bashevkin: Hi friends and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast where each month we explore a different topic balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host David Bashevkin and this month we are continuing our annual exploration of intergenerational divergence. Thank you so much to our dearest friends and sponsors of this series year after year, Danny and Sarala Turkel. I am so grateful for your friendship and support over all these years.

And thank you to our anonymous episode supporter, Moshe. We’re very grateful for you and I really hope we connect soon. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big, juicy Jewish ideas, so be sure to check out 18Forty.org where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails.

This, I believe, is the fifth year that we are approaching Pesach through the lens of intergenerational divergence on 18Forty. Year after year, we have come back to this topic of how generations, parents and children, sometimes husbands and wives diverge and build lives and families even though not everyone within that familial unit is on the same page. By definition, every family is a union of different generations. And we talk about this each year specifically before Passover, before Pesach, because Pesach in many ways is the celebration, the commemoration of the transformation of the Jewish People into a permanent and immutable Jewish family, a Jewish nation. It is beginning with our exit from Egypt that Jewish identity becomes immutable.

If you read carefully the stories in the Torah, in the Bible, beginning with Avraham, so Avraham, or some call him Abraham, he had a child, he had Isaac, Yitzchak, and Yishmael, Ishmael. And only one of them continued the Jewish legacy. We’re the children of Yitzchak. And then Yitzchak also had children. He had Yaakov and he had Esav. And once again there was a question: Are the Jewish People going to emerge from all of his children? And as we see, it only emerged from Yaakov and Yaakov went through this terrifying story where his own children sold one of his own children into slavery, where the brothers sold Joseph into slavery, and Yaakov is crestfallen, Yaakov is so broken. This is how the Jewish People get to Mitzrayim in the first place, is how the Egyptian slavery begins in the first place, how the Jewish People wound up in Egypt in the first place.

And why is Yaakov so crestfallen and why is Yaakov so broken, aside from this fight that’s happening internally in his family, I believe you can read a lot of Yaakov’s pain and suffering in this story was because he considered that perhaps Yosef is going to be like Yishmael, is going to be like Esav, like the children of my father and grandfather, my uncle and great uncle who the Jewish People did not continue through them and their generations and descendants that came out from them are not a part of the Jewish People, and maybe that’s going to be true for me, and maybe not all of the 12 Tribes are going to be a part of the Jewish People. And it’s within that context of that reunion and the Jewish People going into Egypt to redeem their brother, to reconnect and reunite with their brother that the Jewish People essentially begin. It’s the context with which we descend into Egypt in the first place.

So our ascent, our redemption from Egypt is when we emerge from that period of suffering and slavery and persecution, from that period when having the label Jew and being born Jewish is enough to justify persecution, where we emerge from that cauldron of crisis as a family, as united together. And that’s why every year before Pesach to kind of celebrate and honor this occasion where we become a family, we always like to focus on the notion of family within Jewish identity.

And this series has always had a very near and dear place into my heart. On the most superficial level, it is the series that I think brings in many new listeners. They’re very intrigued, there’s something very universal about this type of specificity, this type of just a local story of one family, listening to parents and children talk to each other. There is something very universal about that that really transcends the normal contours of the community that we think of.

I think there is a deeper reason. There is something much more essential that relates to what 18Forty is, what we are trying to build, a revolution. To be very frank and very plain, a revolution in the Jewish world that we’re trying to contribute to. It’s going to take many, many people, but we need a revolution in Yiddishkeit, in our own Jewish identity itself. And that is that 18Forty really began, my partner in this really began this project in the hopes and with the focus of his own family and figuring out a vehicle that could keep the next generation tethered when he saw in his own life, like, that possibility that it could be slipping away.

And I think on the most fundamental level, what 18Forty has been trying to do from the very beginning—if it hasn’t been abundantly clear—it is to remind the Jewish people of our familial bonds, to remind us how to think as a family. Part of what was necessary in order for Yiddishkeit, for Judaism to thrive in America, a land where the first time the Jewish people were really faced en masse with the struggle not of persecution, but the struggle of freedom.

And in a society where you really can choose to be whatever you want, we basically adopted this American ethos. It’s a very American idea that the way to preserve ourselves was through institutions, through schooling, through building synagogues, building our school system, the yeshiva system. This really saved Judaism in America. Families that did not educate their next generation, did not educate their next of kin, quickly assimilated. And we’ve seen it in my own family and I’m sure anyone if you go back and you see the number one preservative of Jewish life in America has been Jewish education and Jewish schooling.

But it has come at a tremendous cost. And that cost, I believe, is that any time you think of your demographic through the lens of an institution, institutions have very clear lines. There’s no institution that can be for everyone. An institution that is for everyone is essentially for no one. You need a specific population that you serve. So a yeshiva has we’re going to serve, you know, this, I will serve just men, will serve just women. We will be a yeshiva for top tier, you know, very intellectual students, will be more experiential. And everyone has its own flavor and is trying to respond to its own specific need that they see within the community.

That leads to a certain institutional thinking in the way that we conceive of our communities, that we kind of gerrymander the lines as we need to, as is necessary in any institution, in any synagogue, in any community. No community can be for everyone, by definition. Everyone is meant to serve and has its own flavor for a certain specific type of person.

The only institution that literally, by design, is meant to serve everyone that is within it is not really a typical institution. It is the family. It is the family that has preserved Jewish life from generation to generation. And a family does not have the luxuries, so to speak, that institutions have. You cannot gerrymander the lines of family. You can’t say I’m only going to consider my next of kin, you know, the smart ones or the athletic ones or the ones who do well in business or get into good graduate schools. We cannot design our families the way that we design our institutions. Family, by definition, is a connection that transcends any merit or any specificity. You’re not going to say I’m only going to have sons, I’m only going to have daughters. You know, we’re a family that’s just, you know, based on gender or age or intellectual capacity or emotional ability or any talents. You cannot draw the lines of family like that.

And in a way, it is very specific, it is a feature of Yiddishkeit and of the Jewish People that we are by design that way, that we have this transcendent root and foundation that connects us to previous generations, something that is unchosen, something that is not a product of any merit. This is what we talk about when we talk about zechus avos, the merit of our forefathers. This is not anything that we did. Our only merit comes from perpetuating this chain and learning how to embrace and find meaning in our unchosen identity, the fact that we are Jewish.

And that’s really the struggle of finding meaning in any family. Families that thrive and are able to stay together is where people find a sense of pride, a sense of joy, a sense of meaning and purpose within their familial ties. It is something that they find nourishing, that they find motivating. Not all families are that way. Some families, a previous generation was so ambitious and so impressive, it’s crushing future generations or other previous generations where, I don’t know, they weren’t as forward thinking, they weren’t as thoughtful. They were too cerebral, too emotional. We have all sorts of issues that we have with our parents sometimes and with previous generations in general.

And I think strong families find that underlying commonality, that unchosen commonality, and they come together and they connect based on that. And I think weaker families sometimes shrivel up. They begin to erode the moment that differences arise, the moment that we’re not all exactly on the same page.

And in many ways, the concern that I noticed, like, the largest concern that I saw from the very beginning of 18Forty is that collectively as a community, we have become better at institutional thinking than we have at familial thinking. And it was time that, as important as our emphasis on institutional building—to preserve Jewish life and community in America—I think it is the greatest miracle that we have the community and the infrastructure that we do. But it has come at a cost and I think that cost in many ways is how we think familiarly, how we relate to our own children, in our own lives, in our own homes, to realize that the rules and the lines and the boundaries with which we think communally should not always be and maybe deliberately can never be the very same lines that we think and we draw within our homes and with our children, with our families.

Yeshiva University puts out this publication called YU Torah-to-Go and they do it around the high holidays and the Shalosh Regalim, Pesach, Shavuos, and Sukkos. And I wrote an article, the title of it was called, “Forgive Me, My King, I Did Not Know You Were Also a Father: On Jewish Peoplehood in the American Orthodox Community.” And the essential idea that I say is that at least in the American Orthodox community, there has been an incredible emphasis of God as King. A king makes rules and has a specific kingdom with very specific boundaries and there are specific regulations.

But we don’t just refer to God as King. We also refer to God as Father, classically in the prayer of Avinu Malkeinu. And I noticed that there was an imbalance of sorts that we have been emphasizing a great deal, and I’m speaking from within the Orthodox community. I’m not presupposing that all of our listeners are Orthodox, but I think each of us, especially since October 7, have kind of come out and seen this wider spectrum of the Jewish world and each of us coming out of that hyper local community that everyone belongs to and you kind of, like, press your eyes together, like you just woke up in the morning and you’re seeing this wider Jewish world.

And everyone from their vantage points has been exposed to something new within our community and you begin to wonder like, do we still have a central vision of a Yiddishkeit, of a Judaism, a vision of Judaism that can encompass the entirety of the Jewish People? I don’t know that we have, nor should we have an institution that can encompass all of us.

But I think the idea of family, if we really leaned into it and understood what that meant, how we connect to our own children and then begun to expand outwards and started to think that way about our local community and then a little bit farther out, I think the entire Jewish world could be uplifted. And this is what I wrote:

“Since October 7th, many shuls, based on the guidance of Rav Schachter, have been reciting the prayer of Avinu Malkeinu during the daily prayer services. We relate to God, as the prayer indicates, as both King and a Father. There are many superlatives that we can use to relate to God — Why are Father and King specifically juxtaposed in this prayer? I would like to suggest that the imagery of Father and King reflect the dual nature of Jewish identity. The Jewish people are both a part of a religion and a family. When we perform religious rituals like brachos, we relate to God primarily as King — the language of a bracha is ‘melech ha-olam,’” which means the King of the world, “not ‘av ha’olam,’” the Father of the world. “A King has rules, regulations, and specific protocols that govern how to approach Him. This is the world of mitzvos and halacha, the formal structure and process through which we bring divinity into this world and into our lives. But Judaism is not just a religion. One of the central tenets of Judaism is the chosenness of the Jewish People. Even Jews who are lax, ignorant, or outright hostile to the tenets of God’s royal sovereignty still retain their Jewish identity insofar as they are still a part of the Jewish People — they are still children within the Jewish family. A child, even a rebellious one, cannot sever their relationship with a parent. The relationship can be strained or difficult, but even a disappointing child is still a child. As Rav Shlomo Fischer points out in his Beis Yishai,” and we’ll try to upload a copy. It’s in Rabbinic Hebrew, but it’s a magisterial essay. “Before Judaism became a religion at Sinai, we were first and remain a family.”

And this is what we try to emphasize on 18Forty, how to reimagine and think how we navigate those familial bonds, especially when they’re strained, not just with generational differences, but with ideological differences. And there is no question that the issue that has really roiled, the issue that has been centered, the frame, the window through which every Jewish person has certainly gazed through over the past two years since October 7, is the question of our relationship to the State of Israel. This is a question that obviously Zionists like myself have looked through and examined and reexamined and really in some ways even repented and did some act of teshuva, of realizing that their gratitude and relationship to the State of Israel was not what it should be.

But even those who the notion of the State of Israel does not carry the same import and importance and significance, and for some who may even critique the State of Israel—this has been the window through which so many of us have centrally been experiencing our own Jewish identity in a very new way, in a way that it wasn’t as centered, even the staunchest Zionists. It feels different since October 7.

And this has been covered both inside and outside of the community. The New York Times, which is never the most reliable place to get your news on Israel, did run an article in December of this year, just a little bit ago, said it can be lonely to have a middle-of-the-road opinion on the Middle East. Some college students and faculty members are seeking space for nuanced perspectives on the Israel-Hamas war on deeply divided campuses. And there is no question that families have felt the tension of discussing this topic. It’s gone in many different directions and different families are navigating different tensions as it relates to this question, this I think existential question for the Jewish People, this extraordinarily central question for the Jewish People.

But I want to remind, as important as this question is, we should not confuse institutional approaches with familial approaches. And while I think it is absolutely important that Jewish institutions take a very strong, affirmative stance in support of the State of Israel—of course, we need that, as should every family and as should every parent—but there’s also a recognition that there is a great deal of diversity in how different people relate to the State of Israel. And sometimes our children, as painful as it may be, do not have the same relationship to the State of Israel that we would hope for or that we would want or that we think is viscerally correct, that we know people, that we ourselves have put our life on the line protecting and preserving, that we have seen families bury children.

So there’s no wonder why this issue is so extraordinarily sensitive. But if there was ever an issue even more important, if one could even say such a thing, but of this equal importance, the underlying importance of the State of Israel, is the fact that it is the ultimate unifier of that Jewish family. It is the Jewish home. It is what unifies us not because we earned it or not because we even necessarily deserve it, but because it is our innate immutable Jewish identity. It is our familial identity. It is the promise of HaKadosh Baruch Hu, of God Himself to Avraham saying, this is the land I’m going to give to your descendants. And we fought generation after generation to ensure that it would go to all of Avraham’s descendants, regardless of their knowledge or their practice, or even of their political ideology, that it was a promise for all generations and a promise that can only be kept if we lean into the underlying immutable bonds of Jewish family.

So as sensitive as this topic is, I hope that we approach this conversation, which is a conversation between an incredible family, two incredible parents, and an incredible son, who are exploring the most divisive issue that one could imagine but ensuring that the ties and the bonds of family are never severed. And in many ways a family that holds on to these bonds is the ultimate expression of what the promise for the Land of Israel is all about: a promise that we will have a Jewish family for generations regardless of how knowledgeable they are, regardless of their specific ideology, regardless of whether or not they are perfectly observant. It’s a promise to a nation and to a family, and the more that we lean in to those bonds of family, the more that we strengthen the immediacy of the revelation of that promise of “lases lecha es ha’aretz hazos l’rishta,” that God’s promise to Avraham that I’m going to give you this land to give to all future generations.

So it is my absolute privilege and pleasure to introduce a conversation between generations about the realization of this very promise. It is my privilege and pleasure to introduce the Dardik family.

We have Judah Dardik and Naomi Dardik, who are mom and dad, and of course, Aharon Akiva, as I overheard him being affectionately called Double A Dardik, Aharon Akiva Dardik, who is a student I believe now in Columbia. We will hear a lot more from all of them. Thank you so much for joining us today.

Naomi Dardik: Thank you for having us.

Judah Dardik: Glad to be here. Thanks.

David Bashevkin: I want to begin, really, when you first noticed that you were not all on the same page in terms of your relationship to the State of Israel and to Zionism. I think most people grow up and they assume, if you went through the regular Modern Orthodox yeshiva education, you’d assume that you come out with certain values and a certain relationship to Zionism and the State of Israel. I’d like to hear first from mom and dad, when was the first time you realized that your son Aharon did not have the same relationship to Zionism and the State of Israel that you likely hoped he would have and you first realized that he was going in a different direction.

Naomi Dardik: I think my first understanding was when there was the moment when you were in the Air Force, when you were asked to load munitions onto a plane and you said no, and there was the showdown between you and your mefaked that kind of led to the rest of the story unfolding.

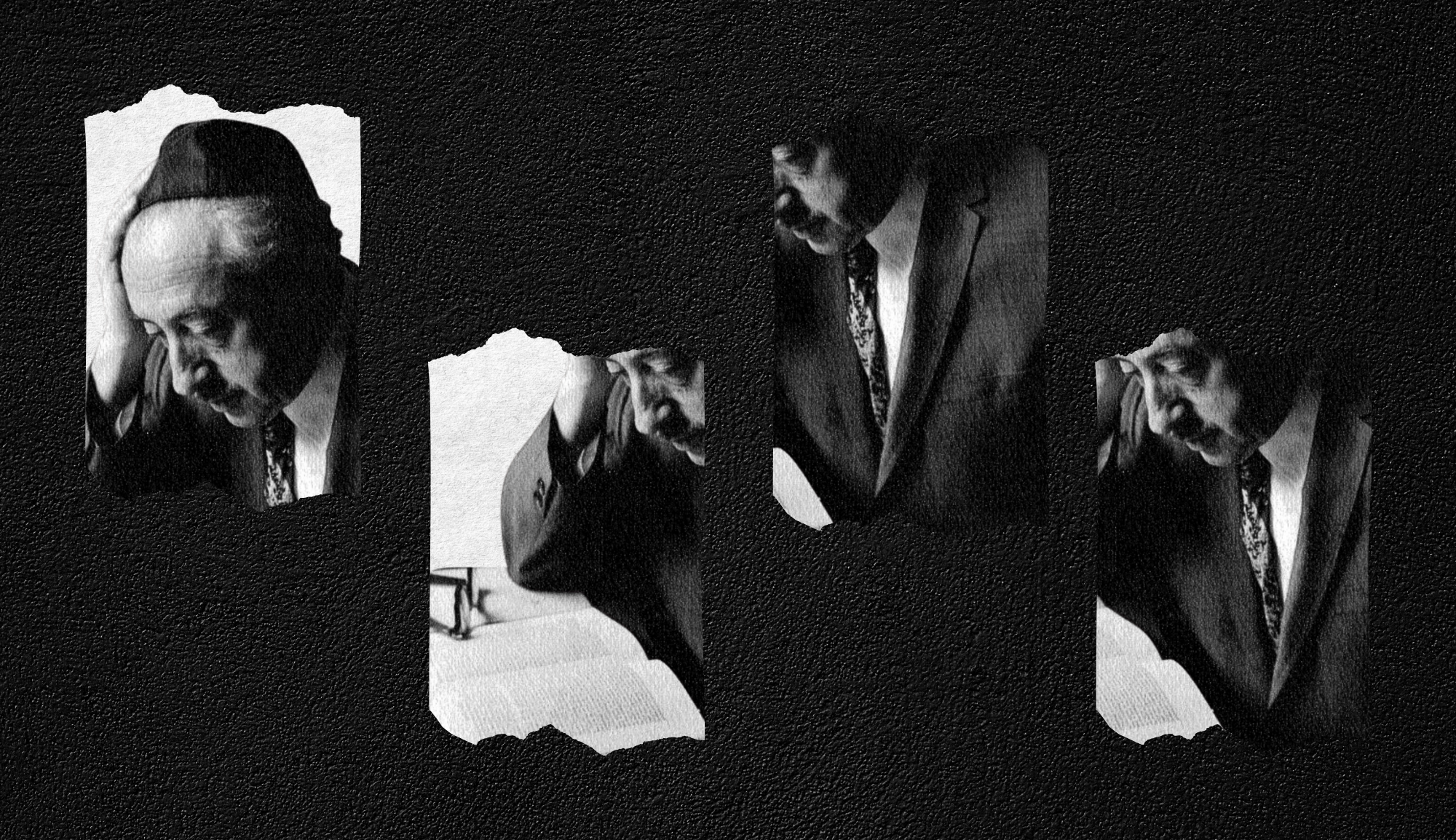

Judah Dardik: Going through high school, preparing for joining Tzahal and likely something in intelligence or where this would go, that’s not the path that ended up unfolding. And ending up in a military job that seemed a great fit in the Air Force, but going ahead. I have a couple of pictures that I still love of you in uniform, Aharon Akiva, from some early times. And commuting back and forth and spending time on a base up north and then a base down south, and it was, okay, so the army career is going to be a little different than we thought, it’s going to be something in the Air Force, fine, we’ll see.

But then finding out, actually no, this really isn’t working and that you really didn’t have intention of going ahead with that, that this was not a fit and that no one was going to make you do anything that you were not morally comfortable with. But that quickly seemed to transition into, actually, is there a way that you’re going to be out of the army? Are you going to stay in Tzahal or no, actually you’re on your way out.

David Bashevkin: So what really fascinates me is that again, you grew up in North America and then you made aliyah. Aharon Akiva, how old were you when you made aliyah?

Aharon Dardik: It was my 14th birthday.

David Bashevkin: On the birthday, bo ba’yom, on the—

Aharon Darkin: On the birthday.

David Bashevkin: On the very day. That is quite the 14th birthday present and celebration. And you had, you know, I guess a high school experience in Israel and you joined the army. Until that point, Naomi, mom, you were under the impression that the family was on the same page, correct?

Naomi Dardik: More or less. I mean, we’re all different people, but nothing radically different.

David Bashevkin: So maybe Aharon Akiva, I could hear from you from your perspective, when did you begin to realize that you were not in fact on the same page generally? And I appreciate that correction Naomi because we’re never literally on the same page, chapter, verse, line, but colloquially speaking, more or less, when did you realize that you were actually not in fact on that proverbial same page?

Aharon Dardik: For me, it was I think a lot more of a gradual process. I’m a person who generally really likes to stick with things and see them through when I am faced with challenges and obstacles. My intuition, my first step, is to say, how can we make this work? How can we reach some form of compromise? How can we make it so that things can keep running as smoothly as possible? I think I have a general intuition that there’s value in the institutions and the processes that we find ourselves in, that we grow up in. As a result, a lot of my, I would say, earlier tensions that I felt with the State of Israel, with the sort of conduct of the Israeli military, were tensions that I was approaching from the mindset of, how do we work this out? How do we get this to a place where this is something that I can ideally endorse and participate in? How can this get to a point where this is something that I can feel comfortable with, or if short of that, something that I can begrudgingly go along with and make it work.

And I think part of that is just a personal disposition. And specifically when it comes to the State of Israel, part of that is the necessity for social survival. There’s no such thing in the community where my family made aliyah to of really opposing the actions of the State of Israel on a fundamental level. In that environment, it’s a really scary thing to say, I don’t want to serve in the Israeli military.

And there were times where I got closer to that. I have a memory of about a month before my draft date, sort of sitting on the kitchen counter and crying about how I wish I could just do national service instead. And since I’ve come out and told my story in some forms as well, I’ve had a lot of people reach out to me and say, hey, I feel the same way, but I’m scared.

And a lot of other people who I’ve talked to who are now in this space who said, yeah, I felt the same way and I was scared and because of that, there was no way that I could maintain a relationship with my family or with my community, and so I’m out, right? I don’t talk to my parents anymore. I don’t talk to my family. I just live within this new space of Jewish left-wing organizing or just left-wing organizing in general, and I’ve lost that connection to my family.

And that’s something that is a very high cost and I think very damaging, sort of like personal relationships and it’s something that’s very sad for me. And it’s something that I was afraid of. And so until, like, the very last moment where it was clear to me that there was no way for any sort of compromise, any sort of way that this could work out, I wanted to keep the acknowledgment of the distance between how I felt and how my family felt about Israel as quiet as possible, because it’s something that’s really scary and I’m very lucky to have the parents that I do and that I think we’re all very committed to making things work even if it’s hard. And it’s something that I probably learned from them. And it’s something that we’re doing, but it’s really not easy and it was a bit scary.

So, I knew that this was something that I didn’t want to do from before I drafted. I didn’t quite realize the extent. Also what I would encounter there would confirm a lot of things that I was afraid of, but it was really hard for that to be something that became out in the open between me and my parents, between me and my family, until it absolutely had to be.

David Bashevkin: Let’s fast forward to that point of where it absolutely had to be, and you kind of had the first conversation with your parents. This is not working for me. Did you speak to your parents together or did you have an intuition that it might be better to speak to one parent over the other?

Aharon Dardik: I don’t think I spoke to them together. It wasn’t about speaking to one parent or another first. And these were conversations that I think we’d been starting to have in the lead up to it when we were talking about potential alternatives. But when it happened and when I conscientiously objected, I don’t think I even remember who I called first, both of them very shortly one after another.

David Bashevkin: Mom, do you remember the first explicit conversation you had with Aharon about this?

Naomi Dardik: I mean, I think you were probably in military jail at that point because the distance between saying, no, I will not follow this order, and finding yourself behind a locked door is not long.

Aharon Dardik: I had about five hours that I think I used.

Naomi Dardik: Okay. We probably spoke that day. And I remember from the beginning, like from your tzav rishon, like from your first draft date, for throughout the process, it was like every communication you had with the army was, I don’t want to be in a position where I will be directly involved in violence or aggression, which was the theory behind, like, you went to a good school, you did the cyber program and the idea was you’ll be in intelligence and that would be, like, okay enough. And then things didn’t work out that way. You know, we hired a consultant to help him with the army process. Like we really tried to figure out how could this work.

David Bashevkin: Can you just pause, because I’m not familiar with that process. What does that mean, a consultant to help with the army process? Is that a common, like, mode of help or support that people reach out for?

Naomi Dardik: I don’t think it’s super common, but kind of like in the U.S. you’ll have a college advisor who’s like an expert on how things work behind the scenes. I think especially for olim, who didn’t grow up here, who don’t really know how this works, who don’t like maybe have friends or relatives who can help advise them, there are a few people who can be hired to fill that role.

David Bashevkin: Interesting. And do you remember, do you have a vivid memory of that call? You get a call from your child. No parent wants a call from their child while they are sitting in any sort of jail, certainly not a military jail. Do you remember that conversation with Aharon Akiva?

Naomi Dardik: I don’t know how much of it is memory and how much of it is reconstructed in my memory. I think it was not shocking, given my, you know, I know him as a person, I know how this has been a struggle and if that’s what he was told to do, and I understand that sergeants are not in the custom of saying, oh, that’s not comfortable for you, okay, well we’ll find you something else to do.

David Bashevkin: That’s—yes, that is not exactly how the military operates. Dad, Rav Judah, maybe you could jump in. Do you remember the first conversation you had with Aharon Akiva about this very real break, this very real dissonance? What was your first reaction? Were you like, okay, we have to take him and maybe redo our Zionist education, let’s get him back to that place, send him to Camp Moshava or some place that will be able to reinspire his relationship to the State of Israel? How did you react when you first realized how deep this break, this point of dissonance was?

Judah Dardik: I don’t remember the initial conversation. I think there was a slight bit more of a surprise to me than it was to Naomi. But it came along. I was like, okay, well, here we are now. My assumption was, there’s got to be a way to make this work. Okay, so he doesn’t want to do this particular job. Clearly, if there’s some conversation or, you know, some bit of time that we can see what works for him, what doesn’t work for him, they’ll find him a different job or we’ll figure this out.

I did not have any really good sense of just how big a shift this was. I didn’t really know how wide the gap was. Because I said, okay, so are we dealing with a situation here where my son doesn’t believe in something that’s so important to me, to our family? I mean this goes way, way, way back from before the kids were born, we were always planning to make aliyah. I fell in love with Israel coming here at age 16 on Mach Hach Ba’aretz. And my exit from that summer was, after I finish high school, I’m going to go serve in Tzahal. One thing led to another and it didn’t end up that way. I ended up going to yeshiva, which was an important experience for me in a very different way. But okay, this is going to happen.

And each one of my kids when they were born, the first thing they tasted in this world was I brought a bottle of Mey Eden to the hospital so I could put a little drop of liquid kedusha in their mouths. And every single one, that was their first intake on planet Earth, was a little bit of Israel, like we’re going to do this.

David Bashevkin: I just need to pause because that is such a remarkable imagery. You took Israeli water into the delivery room and put like a little drop, like almost what they do at the circumcision at a bris milah, they put a little bit of wine, and you placed in the delivery room a little bit of water from Israel because knowing you were that connected to your future plans of making aliyah, and and you did in fact make aliyah.

Judah Dardik: Yeah, I mean, the human body is something like 70% water. This is liquid kedusha, I wanted it in there. I remember congregants, friends of ours who said, we’re going to Israel, what can we get you? What can we bring back? I said, do me a favor, my wife’s pregnant, could you bring me back a bottle of Mey Eden? This was something that was from the get-go. It was never a question of if we make aliyah, it’s when we make aliyah. And we did, and seemed to be going really well, including for you, Aharon Akiva. I remember like you were the first one to make friends. First day, second day. If you play sports, that’s an international language. Go make friends. There it is. This is great, it’s going to be awesome.

So the realization of, whoa, okay, so my views of Tzahal and the value that I place on service, clearly we don’t share that exactly. And I think it was coming as a bit more of a surprise, not a huge surprise, but a bit more of a surprise to me than it was to you, Naomi. So it’s like, okay, so fundamentally we agree. Maybe it’s a quantitative difference, not a qualitative difference. As long as there’s somebody else to load the bombs on the planes, yeah, you’re not really the guy for it. As long as there’s someone else to do it, maybe there’s some other role either in Tzahal or something, but the gap is maybe not an absolute gap. There’s a difference.

David Bashevkin: Just so our listeners understand, this incident that took place where you didn’t want to load the artillery into the plane, this is all taking place before October 7, is that correct?

Aharon Dardik: This is taking place in the lead up to when, like it’ll officially be called Operation Guardian of the Walls, I think two or three weeks afterwards. But it’s an initial strike in 2021.

David Bashevkin: Gotcha. Okay, thank you. So in 2021, this is still pre-October 7, and you get placed in military jail for being a conscientious objector. You don’t want to participate in this. What happens after that? You get released from the army?

Aharon Dardik: It’s this whole process because being a conscientious objector under international law has different qualifications than how we talk about being a conscientious objector than under Israeli law where the burden of proof is on you to demonstrate you’re a conscientious objector, and until then, you’re just someone who’s like refusing to follow orders. And so there’s this whole process of being put into military jail and then serving out your sentence and then coming out and then the army saying, oh, you’re a soldier again because you finished your punishment, come back to work. And then if you’re a conscientious objector, you say, no, I won’t. And they go, again? And they put you back in military jail and the process repeats itself. So I think I had six imprisonments.

David Bashevkin: Before it was, like, finally established. The first time, Aharon Akiva, that you are, like, alone in a military jail in Israel, do you have any memories of where you were emotionally? What is taking place? The door is closed. You’re by yourself, both figuratively and literally, because you’re objecting to something that you know your parents hold quite dear. Do you have any recollection?

Aharon Dardik: I remember crying a lot that day, and I’m not a person who cries that much in general.

David Bashevkin: What were you crying about? Was it just scary or…?

Aharon Dardik: It was scary. It was something that I was really afraid of. There are some things that can remain problems and tensions that while aren’t perfect can be at the very least put off until there’s a better time and place to deal with them, till there is sort of greater clarity about what exactly needs to be done. And I remember thinking at that time that I got neither of those, that I knew that sort of like that I needed to object at that moment, that I had no other option, but that I wasn’t sure what came next. And I didn’t have any sort of community or connections or infrastructure with the broader, I would say, like Israeli left that I ended up being able to connect with—other people who were Israeli and like-minded and want thriving Jewish community and culture in the Land of Israel, but were very opposed to the actions of the Israeli state and the Israeli government often on a very systemic and basal level.

Those people existed, they were out there. I had no contact with them. So at that time, I felt very alone. It was very scary, and I also didn’t know what was going to be next. Especially, my commanders were telling me that if I continued to conscientiously object, that I could be in jail for years. It ended up being four months, but this wasn’t my plan, I guess. It wasn’t what I was hoping would happen, and it carried really serious consequences. And facing those without having anyone else who felt like they understood where I was coming from and why I was doing it was a really daunting challenge.

David Bashevkin: When was the first time time that others in the community, outside of your immediate family, become aware that you were kind of no longer on the path of being typical within the spectrum, whatever typical is, there’s a wide spectrum, but a typical, you know, young Zionist teenager growing up in the Land of Israel. When was the first time that this disagreement between you and your mefaked and all of the consequences and conversations you had with your parents, that circle expanded and now others in the community are aware that there is something brewing within the Dardik family?

Aharon Dardik: There were various moments. It was a bit like, I can’t say if it’s exactly analogous, but some parts of it felt similar to, like, coming out.

David Bashevkin: With, like, sexual orientation, like coming out of the closet?

Aharon Dardik: Yeah, with, like, sexual orientation. Like very close friends knew, but it was also a secret that they weren’t supposed to tell other people. And then like over time, circles grew a little bit more, but it was still something that was kept very hush-hush. And it was really once I came to university in the United States, Columbia now, that I started being more open about it. And obviously that’s something that carries a social cost for me within the sort of, like, established Columbia Jewish community that I’m a part of, but less so than in my community back home.

After I sort of got out of the military, I continued to do activist work on the Israeli left in Israel anonymously. My objection itself was anonymous, and I kept working with refusers’ network and other anti-occupation organizations and equality organizations anonymously. And so I even had like places where I spoke during protests, but I did so like with a mask, like with the hope that I would be not identified.

David Bashevkin: You were wearing like a mask?

Aharon Dardik: Not like a ski mask, like a COVID mask.

David Bashevkin: Oh, gotcha. Okay, not a ski, okay, that would be terrifying. But let me ask you, when you covered your identity, were you more concerned about protecting your reputation or your parents?

Aharon Dardik: My parents. When it came to the objection itself, there is sort of, I guess, a range of responses that the Israeli military is able to take in response to conscientious objection, and one of the key determining factors in what response they take is if there’s a public pressure campaign for them to take one that’s more in line with what the organizations I’m a part of think is the international law legally required response of releasing them.

So, there are these public pressure campaigns and mine was one where I had to be anonymous, and that in some ways makes it harder to build this pressure, but it was incredibly important to protect my parents from the blowback that would ensue.

David Bashevkin: And in a word, why was that so important to you to protect your parents?

Aharon Dardik: I love them.

David Bashevkin: That’s a great reason. This is really the point of tension where the ideologies and ideas that we embrace when they are at odds with our familial identity, that can cause a tremendous amount of pain. I want to hear from your parents now. When was the first time you began to see that your child’s actions were drawing the attention of people outside of your immediate family?

Naomi Dardik: I think during the time that he was in and out of military prison because I also was not, I mean, I was aware that there was an Israeli left. I just didn’t interact with them at all and didn’t, you know, read their materials and wasn’t aware of the details. But because he now needed, like, legal representation and became connected with some of these organizations, I also became more aware of them.

And people were interested in interviewing him, like, here’s a soldier who grew up in a West Bank settlement and he’s objecting. Like, that’s like of interest to those groups and I kind of didn’t want him or our family to become a symbol for, look, even someone from these communities agree with us and kind of being used for their own publicity in ways that would be very complicated for our family and our family’s life. And I didn’t know how that would—I don’t want—I think it’s important that people live in line with their own values, and I didn’t want to say or do anything that would detract from Aharon Akiva’s ability to do that. And at the same time, was there some way for us to find a compromise where he did what he needed to do and thought was right and participated and helped in terms of telling his story and also maybe didn’t expose our family more than necessary to upset and criticism.

And I know that also, like, it’s hurtful. It’s not just, oh, I don’t like it when people are upset with me, which I don’t. But it’s also hard. Like we have friends and neighbors who’ve suffered terrible losses and it’s really emotionally extremely complicated.

David Bashevkin: How do you as a mother respond to community members who are like, how can you allow Aharon Akiva to publicly be involved in these activities? And then, same question, how do you talk to Aharon Akiva and convey to him, like, the magnitude that this is not just, you know, a typical, you know, religious disagreement, you know, how to commemorate Yom Ha’atzmaut, are we saying the Hallel with a bracha, without a bracha. This is something that is so visceral for people. There are people who have buried children and family members who were involved in the very activities defending the Jewish people in the Land of Israel that you have a son protesting.

How were you able to kind of share your own complicated pain with your child?

Naomi Dardik: Okay, two good questions. I’ll say in terms of the community, for the most part, the people with whom I have interacted actively have been very kind and understanding and supportive, not 100%, and in those cases, I tend to get reflective. So if someone says, you know, you don’t have to sign his financial aid form, I will say back, are you suggesting that I cut my child off financially? And then that kind of ends the conversation.

And in terms of my conversations with Aharon Akiva, I really have thought from the beginning that I have a decent understanding of where he’s coming from. I think we have disagreements in terms of, you know, tactics and strategy and the reality of what’s the impact of this, that, or the other decision. But I think that where this is coming from is not wanting people to die, you know, unnecessarily and wanting people to have better lives. We all share the same goals. Our values aren’t different on that fundamental level.

How do we get there? You know, everybody wants to be physically healthy. One person thinks keto is the way to go, one person thinks that whole food plant based is the way to go. We could argue about that. But it’s not like one person thinks life is good and one person thinks death is the way to go. That’s not what we’re disagreeing about. And I think that matters a lot.

David Bashevkin: That perspective that you have right now that you articulated, did that require work for you to arrive at that or that is something that you naturally had always felt in that space between you and Aharon Akiva?

Naomi Dardik: I think it’s how I’ve always felt. Aharon Akiva, tell me if you remember it differently.

Aharon Dardik: I agree. That feels consistent to me. Yeah. To the extent that we’ve had a bit of an arc and a journey about it, it’s about getting to a better understanding and familiarity. That’s really where we’re at.

David Bashevkin: Judah, this might be even more complicated for you in a lot of ways. You’re all part of the same family and the stakes I think are equally high for all of you in terms of keeping a family together and being able to talk. But you also have a role where you teach, where you teach Americans and undoubtedly, part of what you teach are kind of the values and what the relationship to the State of Israel is supposed to be.

How did you deal with the communal criticism or concern for the dissonance that was unfolding in your own home? And then afterwards, I would love to hear how your reaction specifically to Aharon Akiva, how did you maintain that relationship and was it any different than your wife Naomi?

Judah Dardik: There’s a lot there. I would divide it into different stages as you were asking about the earlier times and where the arc went and the development. In the beginning, my recall is that our conversations about being out of the army, conscientiously objecting, I felt very caught between on the one hand, I want to support my son. And if he’s come to the conclusion that this really doesn’t work, and he’s going to go some other way, and we talked about it. He said, like, maybe I’ll do national service. The IDF is not the right fit. Are there ways that I can help society and do good things for people, for Israel that don’t involve military action? So like, I want to support that. I want to be there with him. I certainly don’t want him in prison. That’s on the one side.

And on the other side, being in Tzahal is a value that I hold. It certainly is, Naomi said, a value in our community. The last thing I want is to be talking to someone who says to me, so, what’s your son up to these days? I said, well, I know you just told me that your child is on the front lines and well, you know, mine happens to be objecting right now. I didn’t want to have that conversation. And so to whatever extent we could avoid that.

And just sometimes people say, so how’s it going for Aharon Akiva in the army? I’d say, you know, it’s not really working out so great. You know, sometimes you have a bad fit. People oh, yeah, yeah, that can happen. You didn’t end up in the unit you wanted to be in. Just hoping it would sort of stay quiet as possible. Part of this is being in military prison. Part of it is also going AWOL. So there are times you get leave and you come home for Pesach or Shabbos, and then you just don’t go back. And the first day you don’t go back, you don’t hear much and after a couple of days, they start calling. So one day two officers in proper uniform showed up at the door and they came to deliver a message that just so you know, we are quite aware and you are very AWOL, and we expect you back soon, and if not, there are going to be consequences.

So I said, thank you. Look, I believe in what they’re doing. So I looked at them, I said, I really appreciate you delivering the message. Would you like some cookies? We have some leftover from Shabbos, and they’re parve and they’re kosher and like, I wanted to share with them like my message to them was, I totally appreciate what you’re doing. I hope you understand this message is not going to actually change anything. And I think they’ve been down this path before. So they smiled, one of them took a couple of cookies, they left and so on. But I’m, like, thinking, okay, like did anybody see them come? Is this going to be a topic of conversation? It was generally pretty quiet at least back then.

And as Naomi mentioned, when an organization in [inaudible], well, the fastest way to help him through this process is to be very public. And now I’m stuck because for my son’s good and his interests, what he wants is for this to be public, have his name out there, have his face out there. Let’s do this. And at the same time, I really don’t want that. A, I don’t agree with it. B, it’s really hurtful to my neighbors and my relationship with my community and I don’t want that out there. And I’m trying to balance between the two.

And as Naomi mentioned also, there are different reasons to conscientiously object. The initial response that most people have is, oh, you have a problem with territories. Oh, this is about Yehuda and Shomron. And when it did come up, I said, no, actually, this is about pacifism. This isn’t about like it would be fine if we weren’t living where we’re living or in this space. This is really about, is there a military solution? Is there any way that this goes forward using an army to get towards peace? So we can disagree about that, but at least I didn’t want anybody to think that it was a different message because people are very quick to assume, oh, I know why he’s doing this. You don’t necessarily know why he’s doing this.

So, we kept it quiet then. Definitely felt a sense of tension because we don’t want our whole family to be either A, I mean, people are quick to assume that, oh, if your son believes this, all of you believe this. And I’m thinking to myself, you ever had a kid who didn’t keep Shabbos? Does that mean your whole family doesn’t keep Shabbos? Why is that an assumption that this must have come from home or what not? But so really didn’t want it getting out there and there was some tension over how quiet we would keep this.

And we asked, we said, look, please don’t go public with this while you’re living at home. You have a family, we have to stay here, you’re going to move on. And so it was only really after Aharon Akiva arrived in New York that it was like, okay, look, you’re an adult, you’re a college student, you go do you, and you’ll say what you want to say. And things were relatively speaking, I think, quiet during the initial time up until October 7. But obviously from that date on, there’s going to be a lot of A, tension everywhere. All of us are tense.

David Bashevkin: The whole world is now turning to this question. It’s not just the Dardik family.

Judah Dardik: Yeah.

David Bashevkin: This is now the attention of the entire world. When October 7 first happened, Judah, was there a part of you that is like, uh-oh, this is going to bring this dissonance back to the fore?

Judah Dardik: No, actually. October 7 brought, oh my gosh, are we going to make it? That was the initial—what’s happening now? And it was only a little while later that I became aware that the rest of our family’s feelings, position, thoughts were really quite a bit, you like to use the word divergent, I think on this particular topic of podcast. We were not in the same place and then it seemed like we were heading further and further out. And that with social media, remember the first time around with the army, this wasn’t something that we were putting on social media. But Aharon Akiva is an adult and outspoken person of his values.

And I should say I agree with Naomi, ultimately it’s our values. The disagreement, and this has been one of the points you asked about, how we’ve held it together. So, one of the really important things was to try to zoom out a little bit and realize that if you look at it in a local sense, do you value Tzahal? Do I value Tzahal? So, yeah, we’re now at loggerheads in a very serious way.

If you zoom out a little bit and say, do you value things that we universally value? And then what we’re having is a very substantive and at times more intense than I would like, disagreement about methodology, disagreement about sociology, who are we dealing with here? What’s the best way to get to? But we want the same end goal. That was a really important point that took me a little longer than I’d want to admit to get there. We had some conversations that were not my proudest moments as a parent. But I think in the beginning, I was working from the assumption that, okay, if we just really talk this out, clearly he’ll see the light. Clearly he’ll understand that my analysis of the situation is the correct analysis of the situation, which I think is a normal parenting or human move.

And then after a little while realizing, A, that’s not happening. B, reminding myself, you’ve always got to ask, maybe I’m wrong. As I said, we share the same values, but maybe I’m wrong about the end goal. I don’t think so, but still, we’re going to go ahead and here I have a son who is an adult, who’s a thoughtful person, coming from really, really good values, and that if my instinct, and this is a particular point of sensitivity for me, is that you want to push. So one way to push is you push your point. You raise your voice a little bit or try to insist and hope that somehow you’ll get your message across.

I, in my own personal background, my father and I did not have much of a relationship. He just passed away a little over a year ago, and there were so many times that his response to things that didn’t go the way he wanted was to cut me off. Cut me off, cut my siblings off so many different times, and we’d go years without speaking. And I felt creeping up within me this almost instinctive response of, that’s how you tell your kid that they’ve really crossed the line. The point is that so many times cut off and the instinct that’s rising is, that will show him that he’s crossed the line this time. This is not okay.

And I had to fight that down, bite it back and say, that’s not the way to go. It wasn’t the way to go for me and it won’t be the way to go for my son. It’s not right. He is a good young man whom I love and ultimately, as much as I have care and concern and love for the State of Israel and everything here and it’s passionate. And as much as I, to a lesser extent than my ultimate ideals about Israel, care, of course, about community and friends.

And Naomi’s kind to say that, you know, she can say to someone, be reflective and say, oh, are you telling me this? And they go away. But they don’t necessarily go away, they just come to me. And the conversation keeps going. And so not everyone handles themselves in I think the most socially appropriate ways. And I have to make a choice now. Is my choice that I’m going to be most concerned about reputation, community that aligns with, very much, my values and my view of the best way forward? Or am I going to make a choice and say, you know, that’s really uncomfortable.

And I took this partially from your program. I—listening to Rabbi Penner and, you know, his conversation with Gedalia, this was a couple of years ago, the line that stuck with me so much from that had to do with the idea that my child only has one family. There are lots of people on the campus at Columbia and across the planet who can argue with Aharon Akiva about politics, and none of us happen to be in the State Department of any particular country, so it’s not exactly like we’re the decision makers. But lots of people can argue with him. And I stopped arguing at a certain point because I realized he’s only got one mom and one dad and he’s got his set of siblings, and there have to be some bonds that aren’t breakable.

You can break certain things, and there are definitely tensions, there are moments in our relationship that have been more strained or distant, found it hard to speak. We’ve recently renewed our chavrusa because I want to find the other areas where we can connect. And that’s all really important, but there has to be a line where it’s like, no, I’m not going to cut you off because there are certain bonds that need to remain. And they need to be left and they need to be encouraged. And they’re going to be perhaps in some ways the most important bonds when so many others are falling apart.

David Bashevkin: I could not agree with you more and it’s those familial bonds that’s really our unchosen identity. We do not choose our parents and we don’t really choose our children. They kind of emerge, but it’s that unchosen identity that I think really shapes us more than any of our accomplishments or identities or statuses that we do achieve. Aharon, was there ever a point in your relationship with your mother or father that you were worried this is not going to hold. I’m going to lose my relationship with my parents.

Aharon Akiva: Probably right after my conscious objection, sort of those first initial conversations were the scariest moment. That was the time where like in my head, like it became something that I started being like, huh, should I be preparing for this as a potential eventuality? But the more we continued to talk, even through difficult conversations, the more we were able to set as the baseline that with the Israeli military, with my relationship with the like Israeli state, those are things that you can work on and like if they don’t work out, having a relationship that’s oppositional there is a possibility.

That’s true with a lot of friends as well. But when it comes to family, it’s not. That no matter what happens, no matter what we don’t see eye to eye about, what conflicts we have, I guess like you said, there’s no one like your family but your family. That means that no matter what happens, you have to find some way to have your relationship be the sort of thing that if it can’t work, at least that everyone’s doing their best to set it up to a place where it can work. With me and my parents personally, like we’ve grown enough that it does work and it can work. And so that’s something that I feel like eternal bracha for.

Judah Dardik: Rabbi Bashevkin, you had asked me before about my yeshiva students.

David Bashevkin: Yes.

Judah Dardik: So, just to respond to that question. For the longest time, I kind of didn’t think that they knew, because I’m not on social media. So I just kind of thought, okay, well, if they don’t know, who knows? But they are, and the name Dardik is not all that common. And I have plenty of alumni students who are based in Manhattan, some at Columbia, some at YU, and they’re all around.

Any thought I had that nobody knows were quickly dispelled at a wedding that I officiated at in the US last summer. It was a very noisy room. 12 guys, alumni are standing nearby having a conversation. I can’t hear anything. I happen to be talking to one person. And he asked me something about my family and I was open, and I said, well, you know, I don’t know how much you know. My son and I are not exactly in the same headspace about Israel.

And when all 12 stopped their conversation at a really loud wedding during a dance set and crowded around, I said, do all of you know? Yeah, we all know. Everybody knows. Everybody knows but you because you’re not on social media. You know, I know what Aharon Akiva is saying and we talk about it. But any thoughts I had that my students didn’t know were quickly dispelled. And I appreciated that they were thoughtful, they weren’t saying anything. A couple of them said, well, we don’t want to say anything Rebbe, we thought maybe you don’t know. We don’t want to hurt your feelings. I said I talked to my son very regularly. I know quite well.

And part of what I shared with them was something that in sharing with them, I have to be honest, I was really telling myself, and I think we do that all the time. We tell other people the messages that we’re trying to internalize. And I said to them, look, you know what, the Jewish People have two britot with Hashem. We have the Brit Avot and we have the Brit Sinai.

David Bashevkin: A bris is a covenant, and we have the covenant that we have through the forefathers and foremothers known as the Avos and Imahos. And there’s a separate covenant of Sinai where we received the Torah and the commandments of Jewish law.

Judah Dardik: Correct. And these are the relationships we have with Hashem. One of them is a relationship that is akin, the Sinai covenant, is like a spousal relationship. It’s very, very close. It’s also breakable, and that’s what happens with the golden calf, is we’re breaking that covenant. But the parent-child relationship, which is the covenant of the patriarchs and the matriarchs, the Avot and Imahot, that is a relationship we have with Hashem that’s not breakable. So no matter what a Jew does, no matter how far we go, we say, okay, there’s one covenant that can be broken. The other one is not breakable. It’s there because we are descendants of Avraham and Sarah, period end of story.

So I told that to my students, and I said, listen, I am trying to practice what I preach. And I always tell them, no matter how far you stray, no matter what happened in your life, no matter how far you feel from Hashem, it’s not possible to break the parent-child covenant, the same way that if my small child gets angry at me for saying that, no, you can’t have chocolate for dinner. And they say, you know, I don’t like you, Abba. I say, that’s true. You know, you’re the worst Abba ever. I say, maybe. When they say, you’re not my Abba anymore, I said, that’s actually not true. You can’t change that.

And so I kept reminding myself, and I was telling my students this. So like, I’m telling myself every day, we can differ and there can be strain and there can be times when I’m really genuinely very upset, but this is not breakable. There’s always that parent-child bond. You don’t pick your parents, you don’t pick your kids. And at times that’s frustrating, but at the same time, it has the advantage that the spousal relationship doesn’t, which is it’s not breakable. That one is always there.

David Bashevkin: I’m curious for Aharon Akiva, your father talks a little bit about a shift that he had in his approach with you. There were times where he said, I was not so proud of who I was as a father. I am curious if you have moments where you are not so proud of how you were as a child, as a son, and did you in any way shift your approach either with your work or in the way that you relate to your parents since this divergence emerged?

Aharon Dardik: Yeah, I mean, absolutely. I get the unfair advantage as sort of the child in the parent-child dynamic, and also someone who’s still pretty young. All the things that, like, I regret about how I was handling things early on, I go, oh, well, I was younger then. Sure. I mean, everyone’s younger then.

Speaker B: Everyone’s younger when they’re thinking about past decisions. But do you have specific, you know, you don’t have to get so specific, but were there times where you’re like, you know what? That was not my best child self. That’s on me.

Aharon Dardik: Yeah. I think there are a couple of moments that stick out for me. One, just sort of in the lead up to my conscientious objection. I wish that it was something that I was sharing more about the fullness of how I was feeling with my parents, that my attempts to avoid those conversations were not things that in hindsight I find to be like moments that I’m proud of. I think that in general, being controlled by fear, even, like, legitimate fears, is not a way that I want to be living my life, especially not a way that I want to be defining a lot of the ways in which I relate to my parents.

And afterwards, there are a lot of times where I think there would be assumptions that I would make about some of our baseline shared values that were true but deserved to be repeated. And talking about how I care about Jewish life in the land of Israel, talking about how I care about not just my family and my community, but everyone involved. And talking about how even as I say the things I say and I’m doing the activism that I’m doing, that it is coming from a place and is motivated by the same core values that we share and in many ways by grief that we share towards the tragedies that are occurring in the conflict and that while we have very different ways of going about dealing with that, I think one of the things that I’m trying to do more now is really stressing that despite our different tactics or different strategies, we are still all in this together. And that’s something that I think I wish I made clearer both in my individual interactions with my parents and in things that I would say on social media or whatnot that would end up getting back and becoming topics of conversation.

Judah Dardik: I really appreciate your saying that, Aharon Akiva. It’s been a topic of conversation between us that I feel like in my conversations with you, the person that I hear and the values that I hear expressed aren’t necessarily what sound bites that are put out on social media sound like. And I asked you a few weeks ago, I said like, are you snowing me? Like, are you saying one thing to everybody else and like I’m just getting the sanitized Abba version? And he said, no, no, no. And we talked it through, and I left the conversation yet again feeling reassured that the gap doesn’t have to be as wide as it sounds.

And then asking you again, like please, try to be as clear as you can in your communication. But hearing you say that now, and you know, this is something that other people will hear, to understand that if somebody listens to you and they take something that you say in a certain way or if we’re not absolutely precise in the way we say things and knowing that people have a tendency to hear in what you’re saying what they’re most afraid of, it’s really hard. So I appreciate hearing you say that you’re aware of that. That you’d like to get your message across. We’re not as far as it looks. And thank you. I appreciate that.

David Bashevkin: That was very touching, just to kind of hear the way each of you see this, but I want to bring in mom, Naomi. If I’m reading this correctly, it sounds like the relationship between Aharon Akiva and Judah was more fraught than where you were. And I’m curious, what role, if any, did you take in ensuring, you’re watching, you know, the powder keg. How did you balance your responsibility to your spouse and your child and ensure that you’re bringing them together, strengthening the relationship? Are you circling back and having individual conversations with Aharon Akiva and Judah? Are you ever giving each of them feedback and saying, I think this relationship’s going in a wrong direction or, you know, maybe we should take the topic of Israel off the table? And I’m curious how you as mother and wife kind of factored in to that tension.

Naomi Dardik: I think I have more of an independent relationship with each of them, and generally I take the approach that people will work out their issues between them. And if they want to talk to me about it, they can, but I’m not presuming to take the role of conductor or facilitator if they’re not looking for that. I think Judah and I had more conversations, but he would come to me and say, I just had a hard conversation with Aharon Akiva, and if he wants to talk about it, we’ll talk about it. But I don’t remember suggesting conversations or being more proactive there. People will do things when they’re ready is generally my approach and the social worker in me.

David Bashevkin: Were you ever worried or concerned that their relationship would fall apart, would collapse?

Naomi Dardik: Nah, I have faith in them that they’ll come out. I had a professor in grad school who said, people tell you you’re going to have hard days, they never tell you you’re going to have hard years. And I really, that stuck with me also because, you know, it’s true. We’ve been—Judah and I’ve been married almost 26 years. There have been harder years and sometimes relationships really have very, very deep fundamental problems, but a lot of times it’s, stick around. People will work things out.

David Bashevkin: I’m curious for each of you, you are involved in multiple cohorts. You are not only, you know, parents and children, but you have lives of your own and professional lives. I’d like to hear from each of you on advice you would give to other people in your cohorts, and I’ll start with you, Naomi. Other parents who are dealing with this particular divergence, which is not really spoken about a lot, but we could generalize to really any divergence. What have you found to be the most salient, either advice that you have heard, the most effective approach in ensuring that your relationship with your family ultimately sticks together?

I love what you already said, you know, you can’t always count days. Sometimes it’s going to be a rough year or two or three, whatever it is, but taking that long view. I’m curious what other advice, ideas have allowed you to kind of stay so rooted and grounded. Like, I’m very taken by your disposition. Like, there is a caring but also like, soberness to it. Like, it’s constantly de-escalating and just being very grounded. I’m curious for you, what was the advice, ideas that reverberate in you? What do you attribute your ability to stay so grounded in what could potentially be such a volatile relationship?

Naomi Dardik: That’s a good question. One question that I ask myself frequently when I notice myself starting to spin a little bit is what is this really about? And I remember asking myself that question around this topic years ago when I saw my thoughts going to really, really far out places. And I asked myself, what is this really about? Because I know that if I’m going there, then there’s more to this story than just the story. And what I realized was that I was afraid of losing my relationship with my son.

And that was really scary. If he’s so far out, are we going to lose our connection with each other? Is he not going to want to—is something going to happen? And that, that was really scary. So I could then see how my ideas of, well, what, what if I do this, what if I do that, were all an attempt to kind of force us back into a place of safe closeness.

And then when I realized that, I was like, well, that’s not going to work. Let’s do something else. Meaning, I could threaten. I could basically have an adult version of a temper tantrum, right? To try to get reality to be what I want it to be. And if I understand that what I’m really trying to do with all of these, you know, scenarios in my mind is to try to make sure that Aharon Akiva and I stay close, then I can also take the next step and, well, that’s not going to work. If you say this, if you do that, it’s not going to bring the closeness that you really want. If I can recognize I’m scared of losing him, I’m scared of losing our relationship, then I can focus on that, instead of on other things that are really…

David Bashevkin: Not what it’s about.

Naomi Dardik: Yeah. Yeah.

David Bashevkin: That is extraordinarily moving and I appreciate that. Judah, for you, I’m curious what you have learned about being a father through this. And I’m also curious as a rebbe, as an educator. Do you talk about this more with your students and has this in any way changed the way that you educate and talk about Israel? Has your relationship with your son kind of informed the way that you transmit these ideas to your students?

Judah Dardik: Not directly. In the sense that I think my teaching of Israel, Zionism, the values of the Jewish People and the land are still really the same. I don’t speak about it a whole lot just because I don’t see any reason to do that. If it comes up, I’m not hiding it, but it’s not something that I come in every day and say, hey, my son posted something yesterday, let’s talk about it. It’s not their business. That’s not why we’re there. At the same time, there’s no question in my mind that I have become a better educator because of this. It’s part of the process of becoming a better parent.

All these different lessons, remembering that there’s an unbreakable bond, even if you know I have a reflexive response that says otherwise, that’s not really a good idea, but there’s an unbreakable bond. He only has one father, and nobody ever really changes their mind because you raise your voice at them. You can have a conversation, you can talk about something, but yelling at someone is not going to actually change anything. It’s going to go the other way actually.

Those are things that I thought about, but then it got me to be deeper thoughts. When Naomi was mentioning about, why is this so upsetting to me? Like I’m saying to myself, well, why is it so upsetting to me? He doesn’t work for any government, I don’t work for any government. No one’s exactly asking us our opinion. Like we have our opinions, everyone has their opinion. So why is this getting to me?

I got to something similar, which was that, you know, Aharon Akiva, if you’re taking such a different stand, are you now rejecting my values? Are you rejecting me? What happens now? What are you saying that you think about our family and what we believe and who we are? If you use certain terminology, are you saying that we are guilty of what you think is a crime? What does that mean? We live here, we support this, we’re involved. So I had to dig down a little bit to get to that.

And I think on an educational level, one of the bigger things that emerged for me was a theory, I wish I had a better phraseology for it, but I’ve come to think of my children, and really all children and certainly my students, but all children as effectively, they may be biologically linked to me, but they’re all really foster children. In the sense that Hashem has some neshama and says this neshama is going to go to the Schwartzenstein family, and this neshama is going Goldberg, and that one’s going Dardik. And they don’t arrive in my hands as blank slates that if I just do it right, and I make every correct decision as a parent and I just do everything the way it should be, my kids will turn out as, I don’t know what I’m looking for even. Am I looking for little mini-mes? Not really. They’ll come out the way that I would have thought.

That’s not true. People are born and they have a neshama and Hashem says, I’m putting this one into your care, Judah. This is going to be your foster child. And I’m putting this one into that family’s care. Oh, this is another one for Judah and Naomi. And that our job as parents, and it kind of worked the other way. I said what would I say to my student? My student arrives in my yeshiva as an 18-year-old. And so of course they’re already somewhat formed. And my job now is to say, all right, let me try to see you as well as I can and figure out how to help you develop into an even better version of you. Why wouldn’t I give my child the same courtesy and the same honor to say, look, you arrived in my hands. Granted, quite a bit younger, and I had at that time I had to hold you, I had to feed you. There’s other things I didn’t, thank God, I don’t do that now.

David Bashevkin: You had to feed him Israeli, Israeli water in the delivery room no less.

Judah Dardik: Exactly. Exactly. So here’s my son. We may have started out earlier, but he arrived as a neshama and he is effectively that form of foster child, and so is his next sister, and his next sister, his next sister, his next brother, his next brother, like they’re all different.

And as much as I knew that intellectually, through the process of the last years, it’s become so crystal clear that my job isn’t to make them, neither my students and—now but I realized now my children. I knew it. I said it. I said the words, but to really absorb, my job is to see who you are, what is core to you, and to help you develop that in the best direction possible. And that’s in a sense, it’s made me a better educator because I’m a better parent, and they’re all working around the same axis.

David Bashevkin: That is extraordinarily profound and moving. Aharon Akiva, I’m curious from you, you know, you work in a left-wing activist space, and I’m sure the people who are surrounding you are also children and not everyone is blessed with the parents that you have of their capacity for understanding and care and also your thoughtfulness.

What advice have you received and what ideas have you received that have allowed you to kind of step into being a great child and holding that dear and center? And what advice would you give to other people in your space? Have you ever given advice to other activists and say, you know what? The work we’re doing in our eyes is extraordinarily important, but it should not come at the expense of our families and there is something we could be doing—it’s not always the case—but there are things we could be doing to ensure that our relationship with our families remains intact.

Aharon Dardik I’ve struggled to find a sort of blueprint in, sort of, the left-wing activist spaces for something like this. And as a result, like you’re on a call with the two biggest influences I’ve had in understanding how, like, parents and children ought to be interacting with each other, and very grateful for that. Generally, I think the left-wing thinkers and voices that I have taken inspiration from speak about more like universal concepts of trying to maintain community that I have been able to also internalize and I think when one raises the intensity and in some ways the stakes, apply to sort of parent-child relationships and so when people come to me with questions about how to navigate this sort of environment, the three people I’ll likely be drawing from are my mother, my father, and Gandhi.