Rabbi Yohanan said in the name of Rabbi Shimon ben Yohai: If only the Jewish people would keep two Shabbatot in accordance with their halakhot, they would be immediately redeemed, as it is stated… Rabbi Yosei said: May my portion be among those who eat three meals on Shabbat. (Shabbat 118b)

One of the most powerful and enduring lines about the Shabbos, Rabbi Yochanan tells us that if only we would keep two Shabboses, all will be OK. Why two? And why would two Shabboses have such an outsized effect, bringing redemption with it? This becomes the stuff of unceasing philosophical exploration, as Jewish commentators offer differing options for what these elusive two Shabboses are. Is it just two consecutive Shabboses? Some see the two Shabboses as a reference to the potential sanctification of the week, conceptualizing the two Shabboses as keeping the sanctity of the week and the sanctity of the Shabbos together.

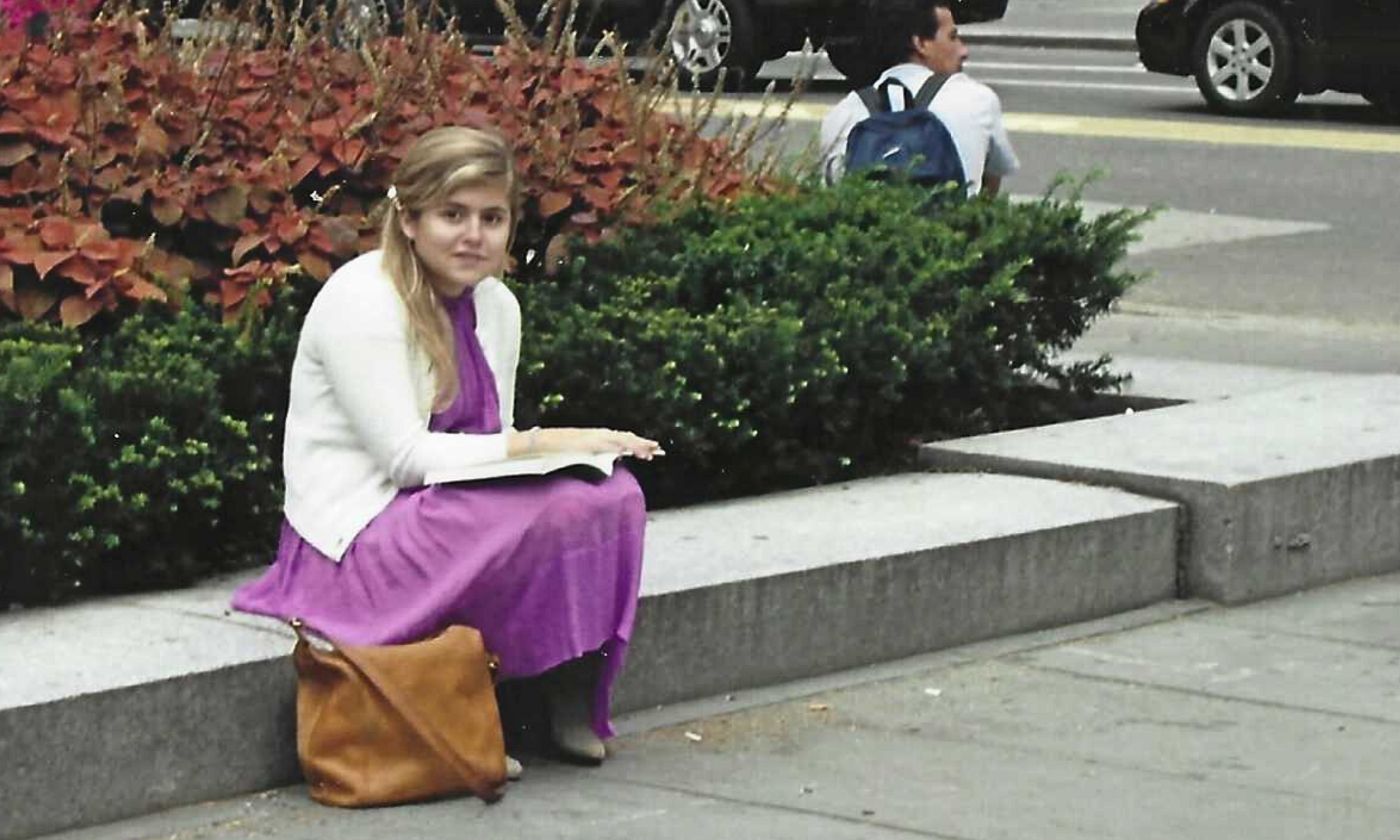

But to realize the answer, we turn to our recent guest, Judith Shulevitz. Judith, a highly accomplished journalist and author, points us to a fascinating text in the Talmud, which wonders about when Shabbos should be observed in a vacuum, a void. Should someone somehow lose their sense of time, perhaps through being lost in a desert, when should they keep Shabbos? One perspective posits that they should wait a week and then keep the seventh day. The debating side urges one to start right away and to immediately keep one Shabbos, and then to wait a week before keeping another.

These symbols produce meaning on a national level, but they are also deeply personal, and each of us choose and cultivate the Shabbos that we dwell in.

What lays at the heart of this dispute? While there are multivalent possibilities, Judith thinks about the two perspectives with characteristic depth, seeing in this text a question about where humanity should go, or can go, after it realizes its own limitations. In the former, we see humanity turning to the imitatio dei it knows so well, turning to divine imitation when it loses its own self-awareness. As God built a world and then, seven days later, built a Shabbos, so too must humanity wait seven days. But in the latter opinion, it is not God we imitate but the primordial humans, who experienced Shabbos after only one day.

While Judith stops here, acknowledging that we have a choice in choosing a Shabbos patterned after God or after Adam HaRishon when it comes to creating our world, we might go further. When cultivating a Shabbos from scratch, in a vacuum, should Shabbos be before, or after? In words that might be more local to us, does Shabbos end the week or begin it? Moreover, might it be both?

Franz Rosensweig, the great Jewish philosopher, and one of the all time great articulators of the Jewish symbolic system, saw in Shabbos an expression of the triangular cycle of time that he saw as fundamental to Jewish meaning making: creation, revelation, redemption. On Friday night, we read (and pray) about the Shabbos of creation, the first Shabbos, as we think back to the creation of the world. On Shabbos morning, we read/pray about the Shabbos of revelation, as we think back to Sinai. And on Shabbos afternoon, we read-pray about the Shabbos of the world to come, as we think back to the distant future of the hereafter.

The Shabbos of the past (creation), of the future (redemption), and perhaps of the present: revelation. This is the tale of the world, our nation, and each one of ourselves as well, in some ways. We are born, we come into our own, we pass, and we are redeemed.

Thus we have a Shabbos that comes before, as well as a Shabbos that comes after, and perhaps we live in the Shabbos that dwells between these two, the present moment in our lives. We aspire to safeguard all moments of this continuum: to create a world of meaning, in the creation, to experience connection and awareness, in the revelation, and to find redemption, freedom. These symbols produce meaning on a national level, but they are also deeply personal, and each of us choose and cultivate the Shabbos that we dwell in.

As we think about the Shabbos that we create, we are thinking of the rituals of Shabbos and how we make them our own. We pair these thoughts with words from Casper ter Kuile’s timely and moving book, The Power of Ritual, from his exploration of time. This read has us thinking about the Shabbos of our lives, and the ways we might find ever more meaning in the practices and questions of our life.