Summary

On June 29, Eden will be hosting a webinar to speak in detail about the vision for this project. In order to register please click here or email info@edenbeitshemesh.com to find out more.

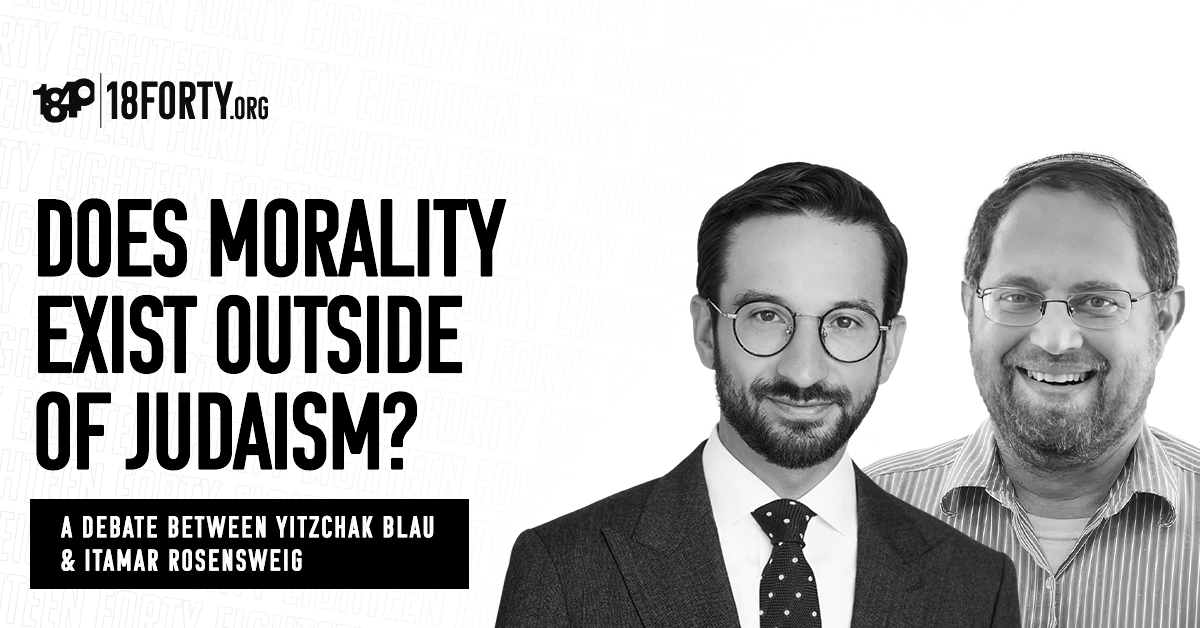

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin moderates a debate between Rabbi Itamar Rosensweig and Rabbi Yitzchak Blau on whether morality exists independently of Judaism.

This is a recording of a live event hosted at Young Israel of Teaneck on May 4. In this episode we discuss:

- What does it mean for God to be good, and who defines the “good” in the first place?

- Do Torah Jews base their values on halacha, or something else?

- Should we make any changes to halachic and moral education in the Jewish community?

Debate begins at 10:57.Rabbi Itamar Rosensweig is a professor of Jewish law and jurisprudence at Yeshiva University, a rabbinic judge and chaver beit din at the Beth Din of America, and the rav of the Shtiebel of Lower Merion. He holds a secondary appointment as an assistant professor of philosophy at Yeshiva College and serves as the chair of Jewish studies at the Sy Syms School of Business. He received his semikha, Yoreh Yoreh and Yadin Yadin, from RIETS, where he was a fellow of the Wexner Kollel Elyon and editor-in-chief of the Beit Yitzchak Journal of Talmudic and Halakhic Studies.Rabbi Yitzchak Blau is the author of Fresh Fruit & Vintage Wine: Ethics and Wisdom of the Aggada and is Tradition‘s associate editor. He has taught at Yeshivat Hamivtar, Yeshivat Shvilei Hatorah, and the Yeshivah of Flatbush and currently also teaches at Midreshet Lindenbaum. Rabbi Blau has a BA in English Literature from YU, an MA in Medieval Jewish History from Revel, and semikha from RIETS. Rabbi Blau lives in Alon Shevut with his wife and four children.

References:

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by C. S. Lewis

Mere Christianity by C. S. Lewis

Fresh Fruit & Vintage Wine: Ethics and Wisdom of the Aggada by Yitzchak Blau

HaEmunot veHaDeotby Saadia Gaon

Religion And Morality by Avi Sagi and Daniel Statman

Plato’s Euthyphro

The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Eight Chapters by Maimonides

Halakhic Manby Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik

A Theory of Justice by John Rawls

For more 18Forty:

NEWSLETTER: 18forty.org/join

CALL: (212) 582-1840

EMAIL: info@18forty.org

WEBSITE: 18forty.org

IG: @18forty

X: @18_fortyWhatsApp: join here

Transcripts are produced by Sofer.ai and lightly edited—please excuse any imperfections.

David Bashevkin: Hi friends, and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast where each month we explore a different topic balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host, David Bashevkin, and today we are debating morality. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big, juicy Jewish ideas, so be sure to check out 18forty.org, where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails.

From the very beginning of 18Forty, one of our dreams has always been to be able to host debates, have live debates, have debates that we record and that we put out there. So much of what we do is have these conversations that clearly have more than one side, that clearly have more than one approach for how they should be resolved or how they should be integrated into our lives. And this is something that I’ve been talking about from the very, very beginning, particularly our co-founder, Mitch Eichen, from the very beginning has always said, I want debate. I want to hear people going at it.

And part of the difficulty is figuring out the right topics to debate. I’m not assuming that morality was necessarily the right one. The reason why we are starting with here is because in my community, there is someone named David Schwartz. He is, I believe, a Yale-trained lawyer, really brilliant guy, gives a shiur, a class, after my class on Shabbos morning, always incredibly brilliant. I consider him a dear friend, even though I am terrible at replying to his emails. The man can send a … he knows how to send those emails. But when we were planning this, there were a lot of back and forths.

But either way, this David Schwartz, who you may remember, if you saw—our shul in Teaneck does a yearly dinner video. And I know every shul, like, loves their dinner video. Ours happened to be genuinely outstanding. And he did a dinner video where he starred when he was honored at our shul dinner, David Schwartz, and it was called “Curb Your Shul Enthusiasm.” The entire video was a spoof on the great Larry David show, Curb Your Enthusiasm. And David Schwartz, who happens to both look and sound and have the mannerisms of Larry David, did an incredible spoof that you can find on YouTube, and we’ll put a link in the show notes, of course. He’s just absolutely fantastic, and I honestly sometimes go back and rewatch it myself.

So anyways, this David Schwartz came up to me and said we want to host a debate, maybe you will moderate. And it was his idea to invite Rabbi Dr. Itamar Rosensweig, who is an old friend of mine, really one of the great speakers, thinkers, dare I say thought leaders within the Jewish world, along with Rabbi Yitzchak Blau, someone whose writing and scholarship I have been following for a very long time.

And each took a different side in this debate of, how should we understand our own moral intuition? Is our moral intuition something that should be shaped exclusively by halacha? That is the position more or less that Rabbi Dr. Itamar Rosensweig took. Or is our moral intuition something that stands almost independent of Jewish law, independent of halacha? And that is more or less the position that Rabbi Blau took in this debate. It’s an incredibly important debate because it really gets to the heart of how we understand ourselves, how we understand our own moral intuition. Is it something that we should be relying upon? How should we understand that voice, that sense, that intuition that resides within us?

Personally, there is an idea that I later found articulated so much more clearly and so much more beautifully in the writings of C. S. Lewis. If you are not familiar with C. S. Lewis, he is really one of the great religious writers. He’s not Jewish, though, fascinatingly, and you can look this up online, he did have a stepson who later on became an Orthodox Jew, a child who I think it was the child of one of his lovers or girlfriends or maybe even his wife that he married who ended up being an Orthodox Jew, was a woman who was Jewish, I believe.

So he has connections, but his writing is just absolutely brilliant. He writes about the religious sentiment, the religious impulse. He does write a lot about Christianity, but nearly all of his writing I find is equally relevant, regardless what specific religious affiliation you have. It’s just so powerful and so beautiful. You probably are familiar with him through the great book, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, which a lot of people read, I don’t know, in elementary school. It was later made into a movie.

I personally love, there’s a great joke that former 18Forty guest and my friend Gary Gulman likes to make when he saw The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe or he read the book, there’s this character named Aslan, I think his name is, he’s this lion figure who’s clearly kind of modeled after a Messianic, a Jesus-like figure, again, it’s written by a Christian, who dies in the middle. And Gary has this great line of how he reacted after Aslan dies in the story. Let’s listen to Gary Gulman’s quick bit on this.

Gary Gulman: Aslan, by the way, the most obvious Christ figure in the history of literature. I called it in fifth grade and a Jew. Because we’re, we were reading Lion, Witch, Wardrobe, which is, which is my abbreviation of The Lion, the Witch and the ... It’s like a lot of times, I’ll just, I’ll take all the articles out. It was, we’re reading Lion, Witch, Wardrobe. We got to the part … we got to the part where Aslan dies.

And the kids were, were distraught. There was open weeping. And I said, hold your tears. If this, if this goes where I think it’s going, he’ll be back on Sunday. So…

David Bashevkin: But leaving that aside, there’s a fantastic idea that I personally, I remember I had this … and I found it articulated so beautifully in C. S. Lewis about our own moral intuition, about that feeling that we step outside and we almost try to indict God. How can this world be yours? It is so immoral. There’s so much suffering, there’s so much pain, there’s so much brokenness. This is what C. S. Lewis writes, which I find to be incredibly powerful. Again, this is from his book, Mere Christianity.

“My argument,” writes C. S. Lewis, “against God,” he originally was not religious, so “my argument against God was that the universe seems so cruel and unjust. But how had I got this idea of just and unjust? A man does not call a line crooked unless he has some idea of a straight line.”

What a brilliant sentence. “A man does not call a line crooked unless he has some idea of a straight line. What was I comparing this universe with when I called it unjust? If the whole show was bad and senseless from A to Z, so to speak, why did I, who was supposed to be a part of the show, find myself in such a violent reaction against it?”

We look at the world and we see all this suffering, all this pain. How can it be, we say, that this is a world of God? It is so unjust. Where did we get that idea from? Where did we get that notion that the world could even be otherwise? What is that intuition that is screaming out within us? Says C. S. Lewis, were it not for God, we never would have that innate intuition of what, you know, the world should ultimately look like, of what, so to speak, a straight line even looks like. And I’ve always found that powerful, which is why I always listen and pay attention to my own moral intuition. I don’t necessarily think that it’s always right, but it’s something that I always pay attention to.

And that is why I think this debate, especially now, I think is a time where we’re really trying to figure out what our relationship is to religious life and religious thinking is … such a beautiful time for really a debate about Jewish ideas. I remember when we came into this debate, Rabbi Blau looked, it was, it was packed. We had like, I don’t know, a few hundred people showed up to this live debate. And Rabbi Blau, who lives in Israel, was shocked. He said, wow, I didn’t realize that so many people were interested in a topic that … it’s not all that practical. It’s not something that you need to make a decision about now or later, but it’s just, it’s people who are hungry to really understand themselves and understand their own religious commitment and religious identity.

And I think now is a moment more than ever where that urge should be nurtured, which is why I am so excited to introduce our debate between my friends, Rabbi Dr. Itamar Rosensweig and Rabbi Yitzi Blau.

MC: Okay, good evening, everyone. I don’t think we’ve ever had this many people in this room, ever. So that I guess speaks to the point that we came to prove tonight. Debates are essential to what it means to be a Jew. We oftentimes have speakers that come and speak and tell us about debates, but much less frequently today, do we actually have the opportunity to watch a debate live between two talmidei chachamim with strongly held views. That’s why we’re so proud to be hosting this event this evening.

I’m glad that David walked in carrying chairs. David Schwartz is the brain behind this entire project. Uh, this was David’s idea already for a year or plus, maybe even more than that at this point. So we want to thank David not just for schlepping chairs, but for everything that he’s done to bring this idea to fruition. Um, we want to give a huge thank you also to Yitzy Glicksman and Shaindy Krimholtz for taking care of logistics for tonight. We want to thank Sophia Lewis, Morty Weinstein, Seth Dimbert, and of course, as always, Dr. [inaudible] for bringing us so many meaningful opportunities to learn together.

I’m just going to introduce our MC, our moderator for the evening, and then I’m going to turn it over to him. Rabbi David Bashevkin does not need an introduction to those of us who live here in Teaneck, New Jersey and probably to anybody with a smartphone in the Jewish community. Rabbi Bashevkin, I could read you his bio, but I’ll just say that Rabbi Bashevkin, you’ve been rejected from a lot of stuff. I got it. Okay. They listen.

Rabbi Bashevkin, many of you may know, may not know, is a member here in our shul. And Rabbi Bashevkin’s a close friend of mine for many, many years, decades, I guess, at this point. And what we know that Rabbi Bashevkin has the opportunity to do, the ability to do in a unique way is to take sometimes difficult, challenging ideas and concepts in Yiddishkeit and bring them to the masses, bring them to us in a way that we can appreciate them and bring them into our real lives. So we’re really so appreciative of the opportunity to have Rabbi Bashevkin here as our moderator. I do want to take a moment to thank Rabbi Rosensweig and Rabbi Blau for being here this evening. Both of whom do not live very close at all to Teaneck, New Jersey. And both have made tremendous efforts to be here this evening. We want to give a tremendous hakaras hatov both to Rabbi Rosensweig and to Rabbi Blau for being here, and I will leave the rest of the evening now to Rabbi David Bashevkin.

David Bashevkin: Good evening, everyone. And it is so exciting to serve as your host for our first of what we hope to be many live debates. And there is something extraordinarily moving about coming together as a community to speak about something that’s actually not all that practical. We’re not asking questions about how to make cholent on Shabbos, how to make tea on Shabbos, but we’re stepping back and asking essential fundamental questions about our practice, about our commitment, about Yiddishkeit itself.

And looking at this crowd who are here to talk and have a debate on the topic of whether or not you need to keep halacha. No, I’m reading that wrong. That’s on me. Debate whether or not you have to be moral. No, also not. 0 for 2. The resolve is so much less exciting once you hear the resolve. There are moral principles and grounds for morality that exist and obligate us independent of the Torah, Judaism, and its teachings, which is a fascinating topic that I could think of no one better than our two guests tonight to speak with.

And I don’t want to take all too much more of their time, but I do want to say at the outset, this is really the person, this has been his idea for well over a year. I know this because he pretty much texts me every morning and every evening for updates on how this is coming along. But really another round of applause for David Schwartz who stuck with this, incredible.

If you will allow me, I will first introduce to take the first side, please give a warm welcome to Rabbi Yitzchak Blau. Rabbi Yitzchak Blau studied at the Yeshiva Har Etzion and at Yeshiva University. He has a BA in English literature and MA in medieval Jewish history, semicha. Rabbi Blau is currently a Rosh Yeshiva at Yeshivat Orayta and also teaches at Midreshet Lindenbaum. Rabbi Blau is the author of Fresh Fruit and Vintage Wine: The Ethics and Wisdom of the Aggada, a book I’ve personally read and very much enjoyed. And he has published more than 25 articles on issues in Jewish thought. An associate editor of Tradition, he lives now in Alon Shvut with his wife and four children. Please give a warm welcome, come on up, to Rabbi Yitzchak Blau.

And secondly, my friend, somebody I go back many, many years. I quote him frequently in articles that I have written, he informs a lot of my own thinking. Rabbi Itamar Rosensweig is a maggid shiur at Yeshiva University, a dayan and chaver beis din at the Beth Din of America, and the rav of the Shtiebel of Lower Merion. He holds a secondary appointment as an assistant professor of philosophy at Yeshiva College and serves as the chair of the Jewish Studies at the Sy Syms School of Business. He received his semicha Yoreh Yoreh and Yadin Yadin from RIETS. He received his BA with honors in—can you relax, Itamar? It’s too much—in physics and philosophy from Yeshiva University and an MA and PhD in medieval Jewish history from YU’s Bernard Revel Graduate School. And when he’s bored, he actually also holds an MA in philosophy from Columbia University and a second PhD—please relax yourself—in philosophy from the University of Pennsylvania. Please give a warm welcome to my dear friend, Rabbi Itamar Rosensweig.

Once again, I want to open the resolve and I want to highlight some of the questions that we need to address in our open statements. The way that tonight is going to work is I’m going to give each side 10 minutes, which is going to be properly timed, to basically lay out their case. Why do I feel this way about the system of halacha and morality? Then we’re going to give each side five minutes of a rebuttal for what they feel are the holes in the other person’s positions. And then we’re going to have a little bit of time where we allow ourselves to open up for questions.

Before we actually start the debate, I want to begin with a little experiment. I’m going to repeat the resolve. There are moral principles and grounds for morality that exist and obligate us independent of the Torah, Judaism, and its teachings. Meaning there are moral principles that are not communicated specifically through the Torah, Judaism, and its teachings.

I am curious, who feels in this room by a show of hands that yes, there are moral principles and grounds for morality that exist and obligate us independent of the Torah, Judaism as its teachings? Who says yes to that question? Fascinating. I’m not going to, keep your hand up. I’m just joking. Keep your hands up. And who says no on the other side? Let’s just see by a show of hands. Put it all the way up so we could see. I believe we have a slight majority as of now. We’ll see if that changes at the end of the evening for that there are in fact moral principles and grounds for morality that exist.

And that is why we will open up with that side. Please give for 10 minutes an opening statement from Rabbi Blau. Lay out for us, what do we mean by moral principles? What do we mean independent of Torah, Judaism, and its teaching? And why do you feel that is so? Rabbi Blau.

Yitzchak Blau: I just want to begin with an apology to Rav Itamar. I think I have a double unfair advantage. One is it sounds like I have the majority of the crowd and I also have 10 relatives sitting in the room. Okay, so it’s really unfair.

So, I’m going to outline three categories or three kinds of reasons why I think we should believe in morality beyond the Torah. Okay, one, I’m actually going to argue that that’s the traditional position. I think it’s very interesting that today people will give a, you know, a session and say, you know, without God, all is permitted and therefore we need religion. That’s become very popular, but I think sometimes positions become popular in modernity that actually were not really the mainstream position.

And just to give some examples, I think if one reads the Rishonim, almost all the Rishonim make it clear that they think there are moral principles outside of Judaism. I’ll just mention a few examples. The Ramban on the Mabul in Perek Vav is trying to figure out why the punishment was for chamas as opposed to other aveirot. And he says cause that, he says explicitly, because this is a sin you should know about without having to hear from a prophet. A person should just know that chamas, let’s translate it as some kind of theft, they should just know that it’s wrong. And if you look at the Chizkuni in Perek Zayin, he says the same thing. says Dor HaMabul could be punished simply because it’s a rational principle to behave with a moral sense. And this goes much further.

Okay, so that’s just in terms of biblical narrative. If we move to more philosophical abstract things, so this is very clear in people like Rav Saadia Gaon in his Emunot v’Deot. And Rav Saadia Gaon asks in the third section, why do I have to adhere to God’s command? And Rav Saadia Gaon says, because there’s a basic principle called hakarat hatov, to have gratitude. He said, if you were created and sustained by God, so therefore you have an obligation towards God. Now, without getting to the specifics of the argument, which is interesting, but many people have pointed out, but if you have to listen to God because of gratitude, that must mean that there is a principle called gratitude independent of God telling you so, because that’s the basis for listening to God. Okay, so clearly Rav Saadia Gaon thinks there is such an inherent moral value called gratitude.

So I’m not going to do all the sources, but I really think it’s kind of overwhelming that the position was, there is this independent ethic. And for those of you that are curious, so two scholars named Avi Sagi and Daniel Statman have a whole book and they’re really extreme. They basically think that nobody till the 20th century thought that ethics depended on God. So maybe they might be overstating the case, but it’s certainly true that in the medieval era, the overwhelming majority of positions and maybe even all, right, thought that there is this independent ethic.

So again, I think it might be an interesting conversation, maybe it’ll come up later, why things have shifted in modernity. I think that is interesting. But again, I think one could say this is actually the traditional frum position. Even if the other position sounds frum-er because everything depends on God, but if frumkeit is also an issue of, you know, adhering to the Rishonim, so I actually have the frum position. Okay, so that is number one.

Okay, number two, that’s just in terms of precedent. But now let’s move to philosophical argumentation besides precedent. And here, I think there’s some very good arguments why we have to say this. Okay, so let’s say we believe we talk about God’s goodness, right? We talk about it pretty frequently. But what does it mean for God to be good if there’s no standard of goodness outside of what God told us? Right? At that point, it’s almost a tautology. Of course, God is good because he defined good and that’s why he meets it. But if I think there’s something out there called the good, separate from what God says, so then I can say, oh, based on that standard, God is good. So I think it’s philosophically easier in terms of certain traditional positions about Hashem.

I’ll just give you a great quote from John Stuart Mill. I wrote it down. This shows you that I’m still in the wrong century. Like, why do I have this quote? Not because I took a picture on my phone, because I wrote it down. I’ll get there eventually. Hang in there. Maybe by the end of tonight.

Itamar Rosensweig: I thought it was because you were quoting John Stuart Mill.

Yitzchak Blau: Okay. Mill said, but to give you the full flavor, okay, so Mill said, why should I obey my Maker? From gratitude? Then gratitude is itself obligatory independently of my Maker’s will, right? As we said before, that must mean there’s such a thing called gratitude. But let’s go to other options. From reverence and love, maybe it’s not gratitude, maybe it’s love of God. Does that get us to escape the problem? Says Mill, but why is He a proper object of love and reverence? Is it because He is just, righteous, and merciful? Then these attributes are in themselves good, independently of His pleasures. So Mill points out that even if I move away from gratitude and say I just love God, but I imagine my love of God is not arbitrary. I love God because there’s certain qualities God has, but that point, that probably means that I admire those qualities per se. Again, unless you’re stuck within this inner circle that I admire God because of what God told me to admire, which I think is problematic.

So again, just to finish the second argument, the first argument was precedent, the second argument was it makes it easier to call God good, to explain why we should listen to God, etc. Okay, let us go to my third category. Okay, my third category has to do with, let’s call it, I don’t know if I should call it the outcome, the effect, the pragmatic results, meaning I think when we’re evaluating philosophical doctrines, one question, of course, is the truth, and I admit I am a truth seeker, but I also think it’s legitimate to ask what impact does a given position have. So, all the truth seekers in the room, you could ignore this third category. Okay, but I do think it’s an important question, right? We can’t always determine the truth so clearly. So it’s worthwhile to ask what impact it has.

So I would like to suggest that it is helpful to take my position, although I think there are dangers, maybe we’ll hear about them from Rav Itamar in two minutes, but I think it’s … my position avoids certain problems. Now, the Ramban talks about avoiding being a naval birshut ha-Torah, being a scoundrel with the Torah’s permission. So that’s a Ramban more about, you know, how much I eat, how much I drink, things like that. But there’s a parallel Ramban on v’asisa hayashar v’hatov, which is about morality. And what seems to be the point? Anybody in any—we always think that we want the best system possible. Guess what? A scoundrel could subvert any system, right? There’s no foolproof system that someone can’t technically meet the rules and yet not really adhere to the whole spirit of what we’re trying to accomplish.

And that’s true about the world of ethics also. So you could have somebody who, you know, I keep all of halacha, but they find a way to, you know, cheat in business anyway and they, you know, based on some Shach and Choshen Mishpat, but they’ll tell you why it’s okay. So I would suggest that if I believe in independent ethic, it’s easier, I don’t know, not foolproof either, but it’s easier to close that hole. Right, you can’t find some obscure acharonish shita that justifies your dishonesty because you just can’t be dishonest, right? It doesn’t matter what Shach Taz machloket plays out. It is simply a principle that one has to be honest.

Do I have a minute left or I’m done?

David Bashevkin: Two and a half minutes.

Yitzchak Blau: Okay, great. Okay, I might, I have a third reason I might win because I might be shorter than my time each time. Okay. Rav Itamar, I’m really being unfair. Okay, I want to expand the second argument, the third argument, excuse me. The third one was to avoid being a navel b’rshut haTorah. But I would say it might be relevant, and this is a little bit more controversial, to cases where my ethic is not so obviously rooted in the tradition. Because one thing I’ll say for the other side, right, I think Rav Itamar could respond, no, but even if I don’t believe in the ethic independent of halacha, I’m supposed to expand based on the halachot that I have. So if I know halacha really is into compassion, and there’s mitzvot, I could list many mitzvot of being a compassionate and benevolent person. So just within the halachic framework, that’s enough reason to be compassionate and benevolent, right? I don’t need an independent ethic.

But what if we talk about things where it’s not clear per se where basing yourself on the tradition would lead you? And I think a great example would be contemporary women’s issues. I think many of us have a sense that there’s an ethical impulse to give women more opportunity, whether it’s in leadership positions, in educational opportunities, and I think if one asks where does that come from? So I’m not sure one can make such a good argument that I’m just expanding upon the tradition, because the tradition has many distinctions between men and women. Okay, as we know, men are chayav to learn Torah, women are not. And at that point one might say, oh, if I expand it on the tradition, I maintain all kinds of distinctions between men and women which we do have in halacha. But the question is to what extent.

But if I say there’s an ethic independent of halacha, I might say, I value … I’ll toss in some terms, I value equality, I value fairness, I value opportunity, and I don’t think that a gender distinction is reason to get in the way of fairness, equality, opportunity when possible. So at that point I’ll say, you know, I don’t need to claim that the weight of the tradition heads in this direction. I could simply claim that I have an ethical impulse that people deserve opportunities to do various important things, right, to give shiurim, to go to Gemara shiur and the like. And that’s why I fall on this side of the debate within our tradition.

So I’m just going to summarize, maybe we had like one, two, 3A and 3B. I think there’s a lot of good reason to affirm an ethic outside of the tradition. Again, number one, I think that is the traditional position. Like just in the interest of time, I didn’t get into Chazal, we could debate Chazal, but certainly in the Rishonim, it’s overwhelming that there is this ethic independent of Torah.

Uh, number two…

David Bashevkin: That’s your warning.

Yitzchak Blau: Okay. How long is the warning?

David Bashevkin: That’s the end.

Yitzchak Blau: Okay. Okay. Number two—so I’ll be extremely quick—number two, it enables us to call God good. And number three, as a pragmatic outcome, it saves us from the ethical navel b’rshut haTorah, and I argue it even goes beyond that and opens up possibilities in cases where the tradition wouldn’t be so clear, such as women’s issues.

David Bashevkin: Really, really excellent opening. Thank you again for Rabbi Blau’s opening. [applause] Why not? Why not? Clapping is free. Clapping is free. It’s not gonna get anybody a trophy. I am morally obligated to say that Daniel Statman who you mentioned is a former 18Forty guest. Yessiree. Okay, there’ll be more of that to come. Let everybody take a deep breath as our debate about halacha and morality and then Rabbi Blau dropped in women’s issues. I felt like … Hakadosh Baruch Hu, protect us in this moment. We don’t want … this is a debate, not a cage match, okay? But please let’s turn it over to my friend, our friend, Rabbi Itamar Rosensweig.

Itamar Rosensweig: Do I get a thank you before my time starts?

David Bashevkin: Big time.

Itamar Rosensweig: Okay. So, first of all, great to be here. I’ll triple the shout to David H. Schwartz for his perseverance. I’ve ignored more texts from David than anybody else in the world. But I’ve also answered more texts than anybody else than my wife from David. So, really yasher koach for dragging me out here and pleasure to be here. Thanks to Rav David for moderating and thank you Rabbi Blau for coming out for this great debate. Now my time starts? Rosensweigs don’t have it in their genetic material to …

So first of all, the debate—I want to be very precise about the resolve. There are moral principles and grounds for morality that exist and obligate us independent of a Torah Judaism and its teachings. That’s what Rabbi Blau is defending: that there are genuine moral obligations totally independent of Judaism, its teachings, and the Torah. I take that to be a very radical position that he’s defending. I know there’s good dialectic about it. Some people came over to me and they said, I don’t know how you’re going to defend your position in the debate. And then a nonobservant ice hockey teammate of mine told me this morning, are you telling me that an Orthodox rabbi is actually defending the opposing view? Not an atheist, an Orthodox rabbi? That’s what my teammate said about your position. So … I got a lot of chizuk from that.

Now, on the substance of the debate I want to point out that Rabbi Blau in his presentation explicitly said, and here I quote, he doesn’t believe that all ethics depend on God. He said that he believes that there is morality, quote, beyond the Torah. And again, quote, that there are moral principles outside of Judaism. So I take that to be defending the position that these are genuine moral obligations totally independent of Judaism, the Torah, and of God, of those various quotes from your presentation.

Now I’m gonna argue that that’s incorrect, and I want to open up my presentation by briefly mentioning three propositions that I defend, that I think we should all defend. One of them, I’ll mention very quickly, I don’t think it’s essential to this debate because I don’t think Rabbi Blau disagrees. And that is—so this is number one—that there is morality within Judaism and Jewish law. I think many of us believe that, that Jewish law is not just like Professor Lebowitz would say, just formal obligations, but these are genuine moral obligations, and Judaism is doing moral work in its commands, in its prescriptions. And moral theory is very much at the heart of Jewish theory. So that’s, I think, proposition number one, that I think we should all embrace.

Now here’s proposition number two. It pertains to a question in metaethics, specifically Plato’s Euthyphro question, which is—I’ll just give you the Jewish version, of course—about the nature of morality. And here’s the question: Are the mitzvos right because God commanded them, or did God command them because they are right? This is Plato’s question. Again, so are the mitzvos right just because God commanded them, so it’s God’s command that gives the mitzvos their moral umph, or did God command them because they are right, in other words, that they are independently right and proper, and God commanded them, simply affirming that independent moral status that they have?

Now, I think we should endorse the view that God commanded them because they are right. So we should endorse the view, from my position, that God commanded them because they are independently right—right independent of His command. And by that I mean, the normative force of any of the commandments, or most … many of the commandments don’t depend on the commands at Har Sinai. Rabbi Blau, I think, mentioned some examples in his presentation of the idea that we believe that there could be genuine moral obligations prior to the giving of the Torah, and that’s why the dor of the mabul was held accountable.

So I think we should endorse the view that there’s genuine moral force to many things out there in the world independent of God having commanded them. And in fact, things like “don’t murder,” God commanded them because they are the right thing to do independent of His command. And I think there’s a very good reason to think that Judaism endorses that perspective.

If I have time I’ll go into greater detail. I’ll give one very quick example. In Bereishis Chapter Nine, the Torah says that a person who spills another man’s blood should be put to death, Ki b’tzelem Elokim, because man is created in the divine image, not because of any command, not because God said you ought not do it, but because of some fact about the nature of human beings. So it’s not contingent on a command. That’s proposition number two that I think we should endorse.

Now here’s proposition number three. Can there be morality without God? Are there genuine moral obligations independent of God, His will, the Torah, Judaism, etc.? Let’s call this the Ivan Karamazov question, because Dostoevsky has Ivan Karamazov propose this notion that if there is no God, then everything is permitted. That’s a very extreme way of putting the formulation. But we could take a more pareve formulation and say that I think on this question, whether there’s genuine moral obligations independent of theism or independent of Judaism or independent of God, I think the position that we should say is that there are not. And so, take away God, take away Judaism, take away the Torah, you wouldn’t have these genuine moral obligations. So, I’m defending the view that there’s no morality outside of Judaism and the Torah.

Now, I think this debate’s going to turn, most fundamentally, on how we think of the nature of religion in general and how we think of the nature of Judaism in particular. Religion, from Judaism’s perspective, I want to argue, is a comprehensive ideology, meaning Judaism lays a claim of monopolizing value. Perhaps the best formulation of this is something the Rambam writes in the fifth chapter of Shmona Perakim, where he says everything a person does should be driven towards the pursuit of their proper worship of God. Whether it’s b’chol d’rachecha da’ehu or the other formulations that the Rambam puts in there, but you could take that as one version of saying that all value derives from the value that religion attributes to it.

So something has moral value in virtue of it furthering some important religious end, and to the extent that it doesn’t, it’s devoid of moral value. The particulars of the Rambam’s formulation don’t have to interest us tonight. The important point is just some version of the claim that religion or Judaism in particular makes a claim of monopolizing value, that there’s no genuine value outside of it, and specifically moral value.

Now, here’s the main argument of my position. Suppose you had a genuine moral obligation to do X. Let’s say, to not cause gratuitous suffering to animals. Let’s say you felt that you had a genuine moral obligation to do that, okay? Now, suppose that God Himself, or Judaism as an extension of that, were genuinely indifferent about whether you were to cause gratuitous suffering to animals. So you believe that you have that genuine moral obligation, but let’s suppose that God were indifferent about whether you caused that gratuitous suffering.

I think we would have to conclude that God is morally flawed because He’s genuinely indifferent about your doing or not doing something that’s a genuine moral duty. So to the extent that you think that there’s these obligations that exist independent of Judaism, then there’s a real moral deficiency in God or in Judaism. Now, I think that’s a repugnant conclusion. I think to the extent that Judaism makes claims of providing Toras Hashem temima or claims about God’s moral perfection, then you have to believe that God Himself wills that you were to do this thing. And if God weren’t to will that, then you wouldn’t have that genuine moral obligation.

So, I think the practical takeaway, as they say in Syms…

David Bashevkin: That was a dig. That was a dig. That was a dig. That was a dig for sure. It’s a deep cut.

Itamar Rosensweig: … is that you can’t have a genuine conflict between morality and Judaism. Because you couldn’t have something that was a genuine moral obligation that was genuinely in tension with the prescriptions of Judaism.

Now, I want to draw a distinction that’s going to be important for the further discussion, I hope. And that is, I think we should distinguish between the epistemology of Judaism or epistemology of the laws and moral obligations of Judaism, and the metaphysics of Judaism, which is just to say, what is it that Judaism actually says or obligates? Meaning, you should distinguish between how do we know what Judaism wants us to do? I have 21 seconds here. How do we know what Judaism genuinely wants us to do? That’s a difficult question. Many kulmusim have been broken and much dyo has been spilled trying to figure out what we’re supposed to be doing as Jews. It’s a very difficult question and in law, it’s the same problem, right? Judges and lawyers, they try to figure out like what does the law obligate us? But that’s different from the question of what does Judaism actually require, which is a metaphysical question, which is what is the substance of Jewish law?

So of course, I agree that there are many difficult questions. We could have moral conundrums about what Judaism requires. Maybe Rabbi Blau’s example of feminism is a good example. But to the extent that someone comes to the conclusion and says, ‘I know that Judaism prescribes that this is prohibited, but morally, I think that it’s obligatory.’ I think that’s an incoherent result. And what you’re really thinking in that case is you’re saying, ‘I’m torn about what Judaism really prescribes.’ And so that’s the right way to think about that conflict. It’s an internal conflict about what it is that Judaism legislates, not a conflict between Judaism and morality.

And I think to the extent that you agree with that, then Rabbi Blau has failed in his mission to convince you that there are genuine moral principles and grounds for morality that exist and obligate us independent of the Torah, Judaism, and its teaching.

David Bashevkin: A round of applause for Rabbi Yitzmar Rosensweig. I saw so many knowing glances and nods as he was quoting Plato and Dostoevsky. Like, yep, classic, classic Dostoevsky.

Itamar Rosensweig: No one nodded when I quoted my ice hockey team.

David Bashevkin: No. We’re now going to move on to the next part of the debate. After laying out their opinions, we are now going to have not a cross, but we are going to have each side kind of address the misunderstandings of the other side. And we’re going to begin going back to Rabbi Blau, who we’re going to give five minutes to.

Yitzchak Blau: Okay. I’m actually going to waste the first 30 seconds of the five minutes to make four points. David Schwartz has been after me, I think, for two and a half years, so it’s a longer … Okay, that’s number one. Number two, the whole night was worth it to discover that Rav Itamar plays ice hockey in his spare time.

David Bashevkin: Agreed.

Yitzchak Blau: Number three, I’m actually thrilled about the crowd. I’d like to believe that, you know, intellectual curiosity is not dead in the Modern Orthodox world. Hopefully tonight shows that it’s not. Uh, yeah, we’ll do with that. That’ll be fine.

Itamar Rosensweig: I think the crowd is for the practical takeaway.

Yitzchak Blau: Okay. So I want to point out one thing about Rav Itamar’s presentation and then give my critique. Notice that he agreed that murder was wrong absent the divine command, but then says that Judaism is all encompassing and for various reasons that becomes the source of all value. So I’ll just point out that that moves him a little bit closer to me. Meaning, if he took the really extreme position, it would be, the only way Cain knew that murder was wrong, there must have been some revelation to Adam that was passed down.

So he’s not really taking the most extreme position possible, which actually might enhance the debate because then maybe we’ll be able to get into the narcissism of small differences. Although I don’t think it’s so small, but … smaller than it could’ve been. So I think if—

Itamar Rosensweig: It’s narcissism of little differences.

Yitzchak Blau: That’s very good. Really good. Did you think about that now or you’ve used that before?

Itamar Rosensweig: First time I used it.

David Bashevkin: Our next debate, our next debate.

Yitzchak Blau: So, I think Rav Itamar’s main argument had to do with clashes, right? I have an ethical condition that’s X and Judaism says Y, and that raises the specter that, wait, I guess God, you know, didn’t really do so well on His morality test. And I agree that clashes is one of the dangers of my position. Just in a 10-minute presentation, you only discuss the strengths, not the weaknesses. Okay, but I will say I don’t think clashes has to go in his direction. And I’ll give you, I guess I like threes. I’ll give you three reasons why.

Okay, number one, I might say that there are moral principles independent of God, but I could view God as the ultimate authority about what’s moral. Like, He’s the best judge. There’s this thing out there called morality. We’re all trying to figure it out. Just fortunately, God is better than the average fellow. So when God says something, I decide that He has figured it out correctly. So that’s a way of maintaining that there is this thing called morality, but yet, I still have to adhere to the halachic system when there is some kind of clash. Okay, so that would be my first model.

Secondly, I think you really have to ask, is there always a clash? Sometimes a clash depends on navigating the tradition. So, what if we saw on certain issues that there is a debate in our tradition, and we certainly debate a lot, including tonight. And then I say, you know, one seems to line up with my moral sense much more than the other. So I think in that case, we don’t have to say halacha’s flawed. We could say we think the authentic position is this one that lines up with our moral sense. Right? To use an example, well, I guess—Rabbi Bashevkin, to keep things safe, I’ll go with goyim and not women. Okay?

David Bashevkin: God bless you.

Yitzchak Blau: Okay. So … because there are many more women in the crowd than Gentiles. Okay. So let’s say there are certain positions in the Gemara that are pretty harsh to non-Jews. And then the Meiri shows up and the Meiri says, yeah, that was the ancient non-Jews who weren’t civilized at all. But if you are umot hagdurot b’darkei hadatot, if you are a nation that is bound by civilized behavior, then the halacha changes. Now, the Meiri might—actually, I shouldn’t say might—he’s not the majority position. What if I say, oh, if I’m like the Meiri, then my ethical conundrum falls away. Right? This non-Jew in, you know, Bergen County who’s nice to me, right? I don’t apply the Gemara standards to him. I apply a different set of standards, which the Meiri set out. And there again, I’m not clashing with halacha. I am saying I am following a certain route within the halachic tradition. Okay, so that would be a second thing to say.

The third thing I’ll say will be the most radical, perhaps the most radical thing I’ll say this evening, although I don’t know where things are going to go from here. I agree that an Orthodox Jew can’t say the Torah is flawed, but an Orthodox Jew can say that rabbis are flawed, which means it could be you could even say that our tradition is wrong on certain things because the rabbis got it wrong.

Now, again, obviously it is more tense to say that about Chazal, but so I’ll make my life a little easy and say, but maybe we would say it about Rishonim and Acharonim. And sometimes the question is just what knowledge is available. So, we’ll go for the trifecta, women, gentiles and homosexuality. Here we go. Okay. So…

Itamar Rosensweig: Is this what you guys talk about in New York?

Yitzchak Blau: If you ever read Rav Moshe Feinstein on homosexuality—and again, to be fair to Rav Moshe, it was a different era—Rav Moshe basically writes, there’s no inclination for such a thing, it must just be an act of rebellion. That’s the only way to understand why somebody wants to be with someone from the same sex. And I think today, even in most Haredi publications, that would not be the position taken. Right? That there is a sense that there really is such an inclination, like, whether we think it’s exaggerated in numbers, we might be allowed to think that. But to think that it doesn’t exist at all, and that everybody who comes forward is just rebellious, I think most of us would find that a hard position to take. So at that point, I think we’d say, and I think with all due respect, Rav Moshe was a great, great man, but given the era and what he knew about homosexuality, so he actually made a mistake.

So I’m just going to sum up. It seems to me, maybe we’ll hear it differently from Rav Itamar, that the bulk of his argument was rested on these kinds of clashes, and the clashes make me forced to choose and then I have to go with God. But I would say again, three things. That one, I could say that I navigate the clash by simply saying God is the best reader of this independent thing called morality. That would be one way. Number two, I could say maybe the clash is not such a clash. I can navigate it. Look at the different positions within our tradition. I could simply identify with a particular position. Thirdly, I would say, again, it is possible, not that God is wrong, but that rabbis are wrong. And maybe in that sense, there might be individual cases where my ethical intuition actually is more correct than the current practice.

David Bashevkin: Note to self, next year, we’re going to make this into a drinking game. Anytime homosexuality, women’s issues or non-Jews, just take a, take a quick shot. A rebuttal now from Rabbi Itamar Rosensweig.

Itamar Rosensweig: Okay, so first, I don’t think Rabbi Blau has shown or even pointed to a single instance where you have a genuine moral obligation that is supposedly independent of God, which is his burden in the debate. I think you’ve shown that there might be cases where you have a moral obligation that’s distinct from an explicit command, but you haven’t shown that there’s any moral obligations that are independent of God or His will, which I think is your burden in this debate. You’ve said a lot about how we could rely on our moral intuitions to decide some of these questions. You pointed to a Meiri.

I think a very natural response is to say that what the Meiri is trying to do is he’s trying to make sense of God’s genuine will. And he’s trying to interpret what is it that Judaism commands? What is it that the halacha is requiring of us in the tradition of Jewish law? You said something about how God can’t be wrong, but the tradition may be wrong. I take it when you say that the tradition may be wrong, you don’t mean that the tradition is morally wrong. You mean that the tradition is an unfaithful representation of the divine will. And if you mean that, then you’re acknowledging that there can’t be genuine disagreement between the divine will and our moral obligation.

So of course, maybe people are struggling to understand and to interpret the tradition, which is what Jews have done throughout the history of Judaism. That’s what most people do when they’re engaging in Talmud Torah. But that’s, as I understand it, an enterprise of understanding, what is it that Judaism requires, not what is it that morality requires in contrast to religion.

So I don’t see how any of that supports your position. Even the notion of relying on an ethical intuition or a moral intuition, a very standard view in the Rishonim, I think you mentioned some of them at the beginning of your presentation, is that part of tzelem Elokim is the idea that God endowed us with intuitions that are in line with His will. That’s what it means to be created in the image of God. So I don’t think any of that points to there being genuine moral obligations outside and independent of the system of Judaism.

I want to rebut something that Rabbi Blau mentioned in his affirmative argument in his opening presentation. He said that if morality depends on God, then there can’t be a standard of goodness for evaluating God’s conduct, something like hashofet kol ha’aretz lo ya’aseh mishpat is not coherent if you think that morality depends on God. Well, I don’t share that concern because we can easily say God’s will is the basis for morality, or to put it slightly differently, God creates certain moral facts in creation, just like He creates physical facts. And then the standard for assessing God’s conduct is to see whether it’s consistent with the will that He legislated at creation.

So you could say, of course, it still depends on God, but you’re asking whether God Himself is acting consistently. So I don’t think you have to have an independent standard of morality totally separate from Judaism and God’s will to make sense of questions like hashofet kol ha’aretz lo ya’aseh mishpat. I think you’re right when it comes to J.S. Mill that we do want to say that God is worthy of worship independent of God willing us to worship Him. I think that’s true, but I think we will say that God is worthy of worship in virtue of some feature of being God, whether it’s His perfection, moral perfection, whether it’s His omniscience, whatever it is, it’s still a feature of God that grounds our duty to worship Him and that makes God worthy.

So, examples like that simply show a version of proposition two, which I explicitly endorse, which is you don’t need God to command you to do something for it to be a genuine obligation. But that’s very different than the Ivan Karamazov question, which is whether morality somehow depends on God. I yield the extra 30 seconds to Rabbi Blau.

David Bashevkin: You two are probably nightmares at like ebbe meetings and like, I can’t even imagine.

Itamar Rosensweig: I’ve only spoken up once at a rebbe meeting.

Yitzchak Blau: I actually detest staff meetings.

David Bashevkin: And I could imagine why. Um, we made reference to a remark that really called back an earlier debate that I would like to bring up today. Rabbi Blau around two years ago penned an op-ed in The Commentator that I think both fairly and importantly criticized the state of moral and halachic education in Yeshiva University. It happened to be directed at the very program in which Rav Itamar and I myself teach, which makes it so much spicier and so much more enjoyable. I wanted to bring that up because I wanted to hear from both of you, and this is really the part that Rav Itamar kept on mentioning as a joke to get more, “when are we going to get to the practical stuff?”

There is a question in how do we educate halachically and morally in our community? And I would hope that these two views translate in some ways not to get overly practical, but at least some reflections on the state of moral and halachic education in our community. Based on your conception of the relationship between morality and halacha, how do you think, if at all, we should be changing the current state of halachic and moral education within our community? Rabbi Blau.

Yitzchak Blau: How much time do I have for this?

David Bashevkin: Three minutes.

Yitzchak Blau: Okay. All right. So, I think there are a couple of things we could do. First of all, there’s a funny aspect of the frum world in which no one will say he’s a frum guy but he’s mechalel Shabbos. There’s a sense that when you’re mechalel Shabbos, you’re not frum. But we talk about, ‘Oh, there are all these white-collar criminals in jail, but they’re frum, so they need a minyan and the like.’ And I think it’s a problem. I understand why that happens. Like that happened because other parts of the world do share our morality to some degree, but they don’t share our need to be shomer Shabbos. So at that point, you identify frumkeit with keeping Shabbos. But in reality, there’s no reason to do that. Right? If you, you know, extort and launder money and cheat on your taxes and the like, you’re not frum. So I think we have to change the discourse a bit. And that would be a good start to generating a more moral community. Okay.

I would also say that I think there are certain things which we shouldn’t need to, you know, have a long discourse about why it’s true. And here I’m going to repeat something I spoke about yesterday. Let’s say we ask, why should religious Jews in Israel serve in the army? So we could be extremely halachic about it. And we could say, you know, there’s a halachic category called milchemet mitzvah. And one of the categories for the Rambam of milchemet mitzvah is helping the Jewish People when they’re in distress. And that’s what we’re doing and that’s why everybody has to come serve because it’s a milchemet mitzvah.

So, Rav Lichtenstein in an article about Hesder said, I don’t need that. Right? We don’t have to debate what’s a milchemet mitzvah. He said, Torah is meant to come together with gemilat chesed. And what could be a bigger chesed than protecting your people in their time of need? And that really resonates with me. Like, when I—again, I’m not here to make fun of another community or criticize—but I think it’s unconscionable that the entire Haredi community does not serve in the army. And I don’t think we have to debate, you know, let’s see pshat in milchemet mitzvah, is the Rambam right, do you need a Sanhedrin? Right? Basic decency should just say, how could it be that other people die for you, lose limbs for you, lose many months of their lives for you, while you sit in the beit midrash? Like how could that possibly be legitimate? So I think our discourse should also shift that not everything has to be seen through a halachic lens. Like some things are just morally obvious.

Okay, so those would be two of my themes in terms of how communal discourse could generate … and this is really not necessarily my debate with Rav Itamar. He might agree with both things. But again, we should identify frumkeit also with honesty and morality. And we should have certain things that are just morally basic.

I’ll just say a third thing just to uh, nag my two colleagues a little bit. Okay, so just understand the uh, Commentator essay. So a few years ago, for the first time, Sy Syms had more undergraduates than all of Yeshiva College, which means there are more people doing business and finance than biology, literature, philosophy, history together. So I do not view this as a great sign for our community. And I think it means that there’s an incredible pragmatic turn. I admit, the Modern Orthodox lifestyle is expensive. I understand the pragmatic turn, but I think it’s a little crazy that 50% of our best and brightest think that, you know, finance and business is the way to go.

And I would argue both in terms of their life practice, I hope I’m not insulting half the crowd here, and also just in terms of what they’re studying in college. Like that’s what college is about, like taking a course in finance? Right? I would think college is about encountering the great ideas of the Western world. That’s what college is about. So I admit this is not about that—if you’re pragmatically oriented, it doesn’t mean you’re immoral. I’m certainly not taking that statement. But I do think a move away from pragmatism is a helpful step towards morality. So that would be my third suggestion. Despite all the economic pressures in our community, to find a way to generate a less pragmatic … I’ll give you one more example, just to make my uncle happy.

David Bashevkin: Oh, woah, easy.

Yitzchak Blau: Can I do one more?

David Bashevkin: Yeah, one more, sure. Go for it. Yeah, yeah.

Yitzchak Blau: Okay, so I have an uncle here who’s one of the deans at Einstein, and right now, we even hear discourse in our community that doctors don’t make enough money to support the Modern Orthodox lifestyle, right? That’s not as good as, you know, high-tech or finance. And wouldn’t that be a tragedy? Like what is a bigger chesed than being a doctor? And to say that, ‘Oh, yeah, but because I need to have a little bit more money, right, I can’t do that.’ I think that is part of a moral stand we have to take.

Itamar Rosensweig: Be a doctor in Philly.

David Bashevkin: He has two doctorates, yeah. Ra Itamar, your thoughts, reflections on the state of halachic and moral education. These are conversations that we have had. We both serve in the Jewish Values curriculum that we’ve developed for the Sy Syms Department, and a lot of Rabbi Blau’s criticisms, Rav Itamar and I were ones … have surfaced ourselves, and I’m curious, in what ways do you differ from Rabbi Blau on this and what are your own thoughts about the current state of halachic and moral education? Three minutes.

Itamar Rosensweig: Let me first respond to the story, the anecdote that Rabbi Blau gave from Rav Lichtenstein, and then I’ll come back to the … because I think the story actually captures maybe the fulcrum where we disagree.

So I take Rabbi Blau’s story as a, you know, what the Gemara would call a ma’aseh listor, a story that contradicts what you’re trying to say. The story purports to show that we’re not looking at these things through halachic categories. But what Rabbi Blau said was that Rav Lichtenstein said he doesn’t look at the obligation to fight in battle through the halachic lens of milchemes mitzvah, instead, he looks at it through the halachic lens of gemilus chasadim. Both of which are halachic lenses. And so, it doesn’t demonstrate that which is supposed to be demonstrated, that there is something genuinely morally distinct from Judaism that is the basis for any of these obligations.

But I want to explain my difference on a personal level, a personal story that I think actually shows or maybe illustrates the point of disagreement. Before Pesach, I was in Israel. I went for a conference of dayanim, but then I ended up going to visit my younger brother, who is stationed on Nachal Oz. That’s the base that was overrun on October 7. So I was at KBY, I drove down 45 minutes. Obviously very emotional being there, to see the soldiers on the border of Gaza. But the um, the striking thing about the war, putting aside the terrible loss of life, is just to see the toll that the war takes on the young soldiers, the young miluimnikim who are fighting, giving up months of their lives away from their families, away from their jobs. Uh, sorry. Okay. I’m not that soft.

Yitzchak Blau: It’s good that hockey players can cry.

Itamar Rosensweig: You don’t need teeth to cry, you know. Similar sense of the genuine sacrifice when spending Shabbos with my cousins in Raanana. These are people who’ve given up their jobs and much of their family life for months to defend the country. So the striking thing about speaking to my brother, I was able to take him out of his base for a couple hours. You know, and he said, ‘It’s an extraordinarily heavy toll.’ He is a musmach of YU, graduated college from YU, was in the Kollel Gavoha in Gush, started a new job in high-tech before the war. And then he had done machal in Golani, but he voluntarily signed up because he had done machal, he voluntarily signed himself up for miluim when the war started. And you know, he said that he’s very proud of course to fight.

But you know, sometimes he asks himself, when he asks himself, is it worth it to, you know, all these sacrifices in your career? Obviously, your job is protected, but if you’re working on a project, you’re not going to be the guy who’s going to develop that project for your manager. But he said, ‘I know it’s the right thing to do because this is a genuine milchemes mitzvah, and that trumps all else.’ And notice, I think my brother didn’t say, ‘Oh, this is chesed.’ You know, it’s like I’m going to wash dishes for a Kollel wife who’s overrun by her hospitality. You know, one can ask whether your duty of gemilas chasadim overrides your obligations to your son, to your wife, to earn a parnassah. But clearly the category of milchemes mitzvah is a distinct category. And I think this is a great example where thinking in those moral terms that the halacha creates actually sets up the right type of hierarchy for your own balancing of your principles and organizing your life.

So I think to say that we could just sit on a sofa and speculate about our moral obligation, ‘Oh, we have a duty to defend others.’ I think that actually cuts against the genius of Judaism in articulating these obligations within a hierarchy. Milchemes mitzvah pushes you with that force. Milchemes reshus pushes you with lesser force. Gemilas chasadim, less. But these categories really do matter, and I think that’s why it’s so important to think in those terms. And I think that’s the amazing tradition that we have as Jews. Was there something about Syms in the…?

David Bashevkin: Let’s give a round of applause to…

Itamar Rosensweig: Wait, let me say something. Let me say, I’ll say 30 seconds.

David Bashevkin: Okay, 30 seconds.

Itamar Rosensweig: 30 seconds on Syms. I would say educationally, I think the right way to think about this, I’m all for studying morality. I have a PhD in political philosophy and legal theory, but I think what we’re trying to do is we’re trying to understand, like, what is it that Judaism commands and what is it that is the will of God. And these are conceptual tools and these are the things that the best and brightest people of the modern history have been thinking about these things. These are of course very useful to understand our tradition, and they sometimes hit on truth also.

But these are true interpretations of what Judaism itself would be commanding and legislating. So I think it’s … I don’t want to say dangerous. I’ve never used the word dangerous. I think it’s just wrong to bifurcate and say, “We’re studying Judaism and we’re studying morality.” There might be pedagogical reasons for doing that, but that’s not what you’re actually pursuing in doing so.

David Bashevkin: A round of applause to Rabbi Itamar Rosensweig, Rabbi Yitzchak Blau. I always like to end my debates with more rapid-fire questions, but we did speak a lot tonight and I would like to keep these fairly quick. There’s so much more to talk about on an evening like tonight. Each of you, can you recommend a favorite book or article related to the philosophy of halacha and the philosophy of morality? So … two recommendations.

Yitzchak Blau: Just too many books.

David Bashevkin: Give us one.

Yitzchak Blau Okay. So for philosophy of ethics, okay, C.S. Lewis has a book called Mere Christianity. The first part is an argument for ethics. The second part is an argument for Christianity. I would like to recommend the first part of the book. Okay? So that’s what I would say in terms of ethics. You know, you might say I’m biased. I found the first part a lot more convincing. Okay, but in terms of philosophy of halacha, let’s go with … does it have to be halacha as it relates to ethics?

David Bashevkin: Give us a book and an article, please.

Yitzchak Blau: Fine, fine, fine. So … Read, let’s go with this. Right, go with Halakhic Man. Even though Halakhic Man might, you might think it’s more in favor of Rav Itamar, but I think it’s more complicated than that. So let’s go with Halakhic Man.

David Bashevkin: Rav Itamar, favorite articles or books on the moral philosophy and the philosophy of halacha.

Itamar Rosensweig: David Schwartz didn’t tell me I had to do this. I wasn’t…

David Bashevkin: You’re tapping out?

Itamar Rosensweig: I’ll just throw in two. I won’t say favorite, but…

David Bashevking: You can handle this.

Itamar Rosensweig: I’ll just … I think in moral philosophy, John Rawls’s Theory of Justice is a good one. And in the philosophy of halacha, I like Haym Soloveitchik’s history of halacha stuff, which borders on the philosophy of halacha.

David Bashevkin: Just your classics, your classics. Love it. My next question, and I really want to hear this from both of you, if you had the ability to choose what the next debate topic that we do is, what do you think is the next topic that you think is important to have a public debate about within our community?

Yitzchak Blau: Okay. Again, too many things to go, but let’s go with different approaches to how we should be studying Tanach. Right? If we think—we can think there are four approaches, I’ll toss out there, academic, literary, traditional Rishonim, and Midrash. What kind of combination of those four should be prevalent in our community?

David Bashevkin: Rav Itamar, what debate would you like to see our community be hosting? I think it should be either about derech halimmud in studying…

David Bashevkin: Of what?

Itamar Rosensweig: I would say Talmud.

David Bashevkin: Okay.

Itamar Rosensweig: Or—not to stereotype myself—or … in virtue of what is something halacha.

David Bashevkin: One more time?

Itamar Rosensweig: In virtue of what is something halacha.

David Bashevkin: Say it again?

Itamar Rosensweig: In virtue of what is something halacha?

David Bashevkin: Oh, in virtue of what is something considered…

Itamar Rosensweig: Yeah, what makes something the law in Judaism?

David Bashevkin: Absolutely, absolutely fascinating. My final question, as always, always curious about people’s sleep schedules. You guessed it. What time do you go to sleep at night? What time do you wake up in the morning?

Yitzchak Blau: I tend to go to sleep about one and wake up at seven.

David Bashevkin: Holy smokes. Rabbi Rosensweig.

Itamar Rosensweig: I’ve been … I’m not answering this.

David Bashevkin: We’ve all been waiting. Don’t tap out of this. Don’t you dare tap out of this. Your father did. Don’t you dare.

Itamar Rosensweig: Whenever I listen to the 18Forty Podcast, I’m like, I can’t believe these guys answer you.

David Bashevkin: Honestly, I did interview…

Itamar Rosensweig: You think the same.

David Bashevkin: I interviewed his father, would not answer the question. He wanted to know, why do you need this information?

Itamar Rosensweig: What did you say?

David Bashevkin: What?

Itamar Rosensweig: What did you say?

David Bashevkin: I said it’s easier than showing up outside your house and looking through the window. Let me know.

Itamar Rosensweig: Yeah. Wow, the social pressure here is so strong. I would say that I’m up at 5:45 these days, but I try to go in to sleep a little earlier.

David Bashevkin: And our…

Anonymous: When do you play hockey?

David Bashevkin: Our final question, if we could do it one last time, the resolve for tonight: there are moral principles and grounds for morality that exist and obligate us independent of the Torah, Judaism, and its teaching. Who here agrees with Rabbi Blau? There are moral principles, grounds for morality that exist, obligate us independent of Torah Judaism, and its teachings. Show of hands. And who here agrees with Rabbi Rosensweig? I think he won over a couple of people. That’s what we see, won over a couple of people.

Final round of applause. Thank you all so much. Thank you so much to the rabbis, the Young Israel of Teaneck, our debate hosts, to David Schwartz, to Sophia Lewis, Morty Weinstein, Seth Dimbert, Daniel Lowe, and the adult education committee. Wishing everyone an excellent evening.

Yitzchak Blau: Excellent job. Really excellent.

David Bashevkin: That story that Rav Itamar ended with, which really caught me off guard. I don’t normally, I’ve never seen him really become overcome with emotion like that, but I found that story to be so incredibly powerful to say that it’s not enough to just have a moral intuition, especially not when our obligations, our moral obligations come at the expense of others.

And to have a system, a halakhic system, that brings order to our life, that brings prioritization to our life. To be able to live in a generation where people are looking at their own families and their own children and saying, I’m sorry, I have to go fight in a milchemes mitzvah, in an obligatory war to protect the Jewish People and the Jewish nation. To live at a moment where people are saying those words, to live at a moment where people are literally making the greatest sacrifice for the security and strength of the Jewish People. It is absolutely incredible.

And I think for us, an understanding of that moral intuition that we each have, as Jonathan Haidt says, morality can both bind and blind. It binds us into ideological teams that fight each other as though the fate of the world depended on our side winning each battle. So it binds us. We know who our team is, so to speak.

But morality also has the capacity to blind us. And it blinds us to the fact that each team is composed of good people who have something important to say. And I think when we look at this moment within the Jewish People, there are so many debates, so many very important, high stakes, high consequences questions that are facing the Jewish People. And I think now more than ever, especially when we look internally, is important that our intuition, our understanding of morality and ethics serves to bind us to one another, to be part of this fight for the security and safety of the Jewish People and not, God forbid, blind us into internal fighting and internal squabbles and internal difficulties that will hamper our ability to ultimately bring divinity into our lives and for the entire world.

So thank you so much for listening. This episode, like so many of our episodes, was edited by our incredible friend Denah Emerson. Denah, you keep on being more and more heroic. I cannot thank you enough.

If you enjoyed this episode or any of our episodes, please subscribe, rate, review, tell your friends about it. You could also donate at 18forty.org/donate. It really helps us reach new listeners and continue putting out great content. You can also leave us a voicemail with feedback or questions that we may play on a future episode. That number is 212-582-1840. Once again, that number’s 212-582-1840.

If you would like to learn more about this topic or some of the other great ones we’ve covered in the past, be sure to check out 18forty.org. That’s the number 1-8 followed by the word forty, F-O-R-T-Y. 18forty.org, where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails. Thank you so much for listening, and stay curious, my friends.

Recommended Podcasts

podcast

Haviv Rettig Gur: ‘Hamas is upset the death toll in Gaza isn’t higher’

Haviv answers 18 questions on Israel.

podcast

Yehuda Geberer: What’s the History of the American Yeshiva World?

We speak with Yehuda Geberer about the history of the yeshiva world.

podcast

Alex Clare: Changing in Public

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Alex Clare – singer and baal teshuva – about changing identity and what if questions.

podcast

Aaron Kotler: Inside the Lakewood Yeshiva

We speak with Rabbi Aaron Kotler about the beginnings of the American yeshiva world.

podcast

The Dardik Family: A Child Moves Away From Zionism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Judah, Naomi, and Aharon Akiva Dardik—an olim family whose son went to military jail for refusing to follow to IDF orders and has since become a ceasefire activist at Columbia University—about sticking together as a family despite their fundamental differences.

podcast

Julia Senkfor & Cameron Berg: Does AI Have an Antisemitism Problem?

How can our generation understanding mysticism, philosophy, and suffering in today’s chaotic world?

podcast

Micah Goodman: ‘I don’t want Gaza to become our Vietnam’

Micah Goodman doesn’t think Palestinian-Israeli peace will happen within his lifetime. But he’s still a hopeful person.

podcast

On Loss: A Spouse

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Josh Grajower – rabbi and educator – about the loss of his wife, as well as the loss that Tisha B’Av represents for the Jewish People.

podcast

What Garry Shandling’s Jewish Comedy Teaches About Purim

David Bashevkin speaks about the late, great comedian Garry Shalndling in honor of his 10th yahrzeit, which is this Purim.

podcast

Einat Wilf: ‘Jews Are Never Allowed To Win, and Arabs Are Never Allowed to Lose’

The true enemy in Israel’s current war, Einat Wilf says, is what she calls “Palestinianism.”

podcast

Pawel Maciejko: Sabbateanism and the Roots of Secular Judaism

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to historian and professor Pawel Maciejko about the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, Sabbateanism, and the roots of Jewish secularism.

podcast

Alex Edelman: Taking Comedy Seriously: Purim

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David is joined by comedian Alex Edelman for a special Purim discussion exploring the place of humor and levity in a world that often demands our solemnity.

podcast

David Aaron: ‘I believe that the Divine is existence and infinitely more’

Rabbi David Aaron joins us to discuss ease, humanity, and the difference between men and women.

podcast

When A Child Intermarries

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to a son who almost intermarried, the mother of a daughter who married a non-Jew, and Huvi and Brian, a couple whose intermarriage turned into a Jewish marriage—about intergenerational divergence in the context of intermarriage.

podcast

David Bashevkin: My Mental Health Journey

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David Bashevkin opens up about his mental health journey.

podcast

Leah Forster: Of Comedy and Community

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, David sits down with Leah Forster, a world-famous ex-Hasidic comedian, to talk about how her journey has affected her comedy.

podcast

Yakov Danishefsky: Religion and Mental Health: God and Us

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Yakov Danishefsky—a rabbi, author and licensed social worker—about our relationships and our mental health.44

podcast

Elisheva Carlebach & Debra Kaplan: The Unknown History of Women in Jewish Life

We speak with Professors Elisheva Carlebach and Debra Kaplan about women’s religious, social, and communal roles in early modern Jewish life.

podcast

Menachem Penner & Gedalia Robinson: A Child’s Orientation

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Rabbi Menachem Penner—dean of RIETS at Yeshiva University—and his son Gedalia—a musician, cantor-in-training, and member of the LGBTQ community—about their experience in reconciling their family’s religious tradition with Gedalia’s sexual orientation.

podcast

Michael Oren: ‘We are living in biblical times’

Israel is a heroic country, Michael Oren believes—but he concedes that it is a flawed heroic country.

podcast

Rachel Yehuda: Intergenerational Trauma and Healing

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we pivot to Intergenerational Divergence by talking to Rachel Yehuda, a professor of psychiatry and neuroscience, about intergenerational trauma and intergenerational resilience.

podcast

Why 1840?

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we sit down for a special podcast with our host, David Bashevkin, to discuss the podcast’s namesake, the year 1840.

podcast

Talia Khan: A Jewish Israel Activist and Her Muslim Father

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we talk to Talia Khan—a Jewish MIT graduate student and Israel activist—and her father, an Afghan Muslim immigrant, about their close father-daughter relationship despite their ideological disagreements.

podcast

Netta Barak-Corren: ‘I hope that Gaza will see a day when it is no longer ruled by Hamas’