David Bashevkin: ‘We are meant to teach the world how to embrace unchosen identity’

David Bashevkin discusses how to embrace holiness, the purpose of prayer, and the search for meaning in an age of distraction.

Summary

This podcast is in partnership with Rabbi Benji Levy and Share. Learn more at 40mystics.com.

What does it mean to live a Judaism that fits into our lives? David Bashevkin explores the meeting point of mysticism and modernity.

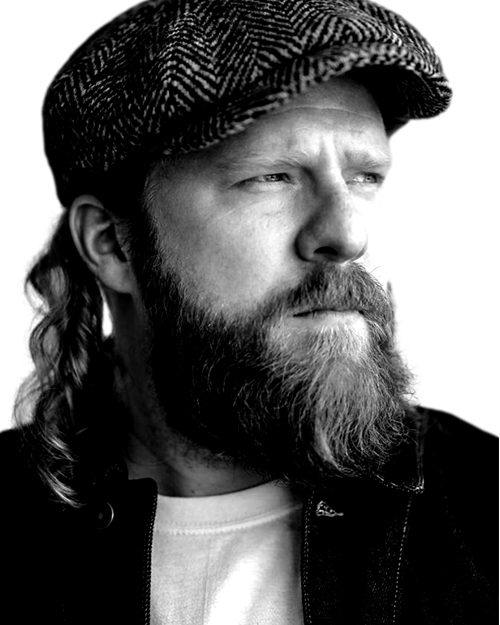

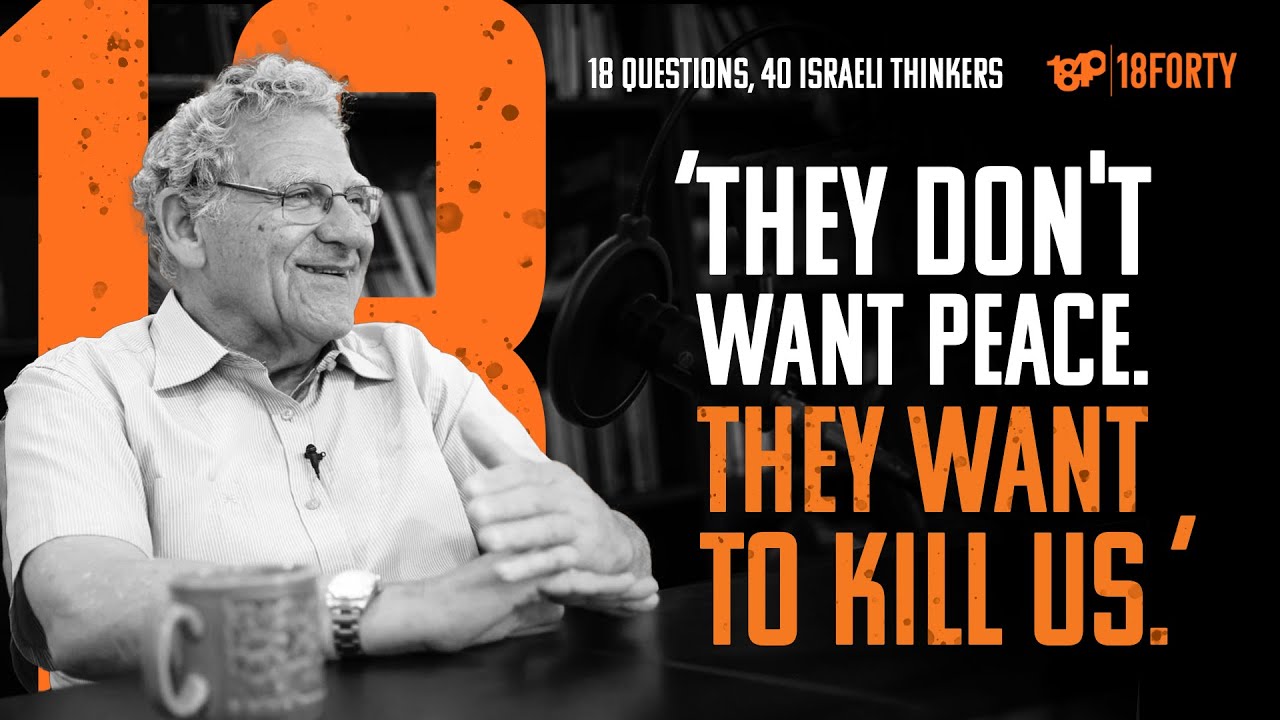

The founder of 18Forty, Rabbi Dr. David Bashevkin is the director of education at NCSY as well as an instructor at Yeshiva University. He is the author of four books, and has been rejected from many prestigious fellowships and awards.

Now, he joins us to answer eighteen questions with Rabbi Dr. Benji Levy on Jewish mysticism including how to embrace holiness, the purpose of prayer, and the search for meaning in an age of distraction.

RABBI DR BENJI LEVY. Rabbi Dr. David Bashevkin, it’s a privilege and pleasure to be with my dear friend, which I’ve heard you say about so many other people in your incredible podcast, but you know, the founder and host of 18Forty, teaching across America and really across the world, writing for so many people. Thank you so much for joining us.

RABBI DR DAVID BASHEVKIN. And just to be sitting with an old friend is really, really special.

LEVY: So, people see you in different lights and in different ways and you’re really one of the most incredible interdisciplinary thought leaders of our time. One of the areas that sometimes peers through is mysticism. I’d like to focus on that today and understand what is Jewish mysticism.

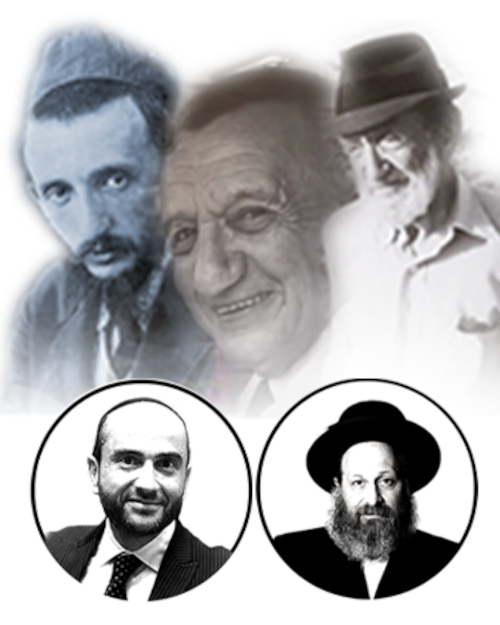

BASHEVKIN. So I come from a very particular school of thought. My interaction and relationship to Jewish mysticism comes through the lens of a Hasidic thinker who I’m sure we’ll be hearing a lot from over the course of our conversation and that is Rabbi Tzadok HaKohen MiLublin, a Hasidic thinker who was born in 1823 and died in 1900. And I was attracted to him because of that interdisciplinary nature of his writings, the way he weaves together halacha, which is Jewish law, and Kabbala, Jewish mysticism, Hasidic thought. His life itself was interdisciplinary. He was raised in a non-Hasidic home and he later became Hasidic.

And he has an essay called “Sefer Zichronot [Book of Memories],” in which he goes and he writes on each mitzva in the Torah. And in that essay he has a very long piece that considers what is the definition of Jewish mysticism? What is it? So he describes that Jewish mysticism is described in the Talmud in tractate Chagiga as something that is nistar, that is hidden. So Rabbi Tzadok explains that the reason why mysticism is called something that’s hidden is not because we need to hide it. He says that’s something that the Talmud adds on, but from the name alone there is something hidden about mysticism. And Rabbi Tzadok explains that the nature of Jewish mysticism is never the words on the page. It is never the work, the book, the page, the ink.

Mysticism, Jewish mysticism, is experiential. It is what you are able to experience and it is the interpretation of finding, seeking, and discovering divinity within your experiential life.

LEVY: So how were you introduced to Jewish mysticism?

BASHEVKIN. I think the first time I was introduced to Jewish mysticism, I had many teachers, but the first time that I felt overtly that I was hearing something otherworldly, that I was hearing something that was from beyond, and I realized at that point that that’s what I’ve been hearing my entire life from my mother, from my father, from my family – the first time I had that experience, I know exactly where I was sitting. It was on a Thursday night. I was in twelfth grade. I was in high school. I was eating a beef and broccoli from Wok Tov, which is the local Chinese store in the Five Towns. I think it was F-14; that is what it was on the menu, and I was at a mishmar that was being run by Rabbi Moshe Weinberger, who at that time was still a young, I wouldn’t call him up and coming, he was established, but he was giving a mishmar in a high school.

LEVY: A mishmar is like a Thursday-night, late-night learning.

BASHEVKIN. A mishmar is like a Thursday-night, extra learning. It’s, like, semi-optional, one of those types of things. And I’m eating my Chinese, and I remember with the beef and broccoli, and he gave out a work that was actually, I now know, Rabbi Tzadok, and Rabbi Tzadok’s first work of Chasidut [Hasidism] is called Tzidkat HaTzadik. And in Tzidkat HaTzadik he had us open to the 154th paragraph. The paragraphs are all numbered. And the paragraph, he was going to begin reading and he looked at the room, we’re in twelfth grade, I’m eating, shoveling it in. He says, to really appreciate this you have to put away your Chinese food. For a moment. And I was like, I’m in twelfth – what Torah can’t be said in front of beef and broccoli? I mean, what are you [saying]? And I put away the Chinese food and he read just in a very sweet voice the words of Rabbi Tzadok.

And Rabbi Moshe Weinberger has a very haunting, very resonant voice. It pulls you in. And the words of Rabbi Tzadok in Tzidkat HaTzadik, in the 154th paragraph is, keshem shetzarich adam lehaamin baHakadosh Baruch Hu, just as a person needs to believe in God, kach tzarich achar kach, so too afterwards, tzarich lehaamin be’atzmo, you have to also believe in yourself. And I was at a point in my life where I didn’t really believe in myself. It feels like a cliche to have you brought in, but it’s only a cliche if you’ve never actually experienced what it means to lose faith in yourself and in your life. And I was at that point where I was really grappling with me, with my own life, who am I? And just the words of Rabbi Tzadok hit me in a way that stayed with me. And it pulled me into the world of Hasidism and the world of Kabbala and the world of mysticism, something that has occupied much of my thought and much of my writings to this very day.

LEVY: It’s amazing how you have such a vivid memory of that and how it sort of penetrated you in such a deep way from the menu, to the food, to the words. But it obviously has that kind of impact. Is that what it meant when you said otherworldly? Is that what you mean by experiential? Meaning it wasn’t just on a page, it’s something that you felt.

BASHEVKIN. In the thirty-seventh chapter of Psalms it describes the giving of the Torah. The Talmud, in fact, uses this verse to explicate all the stories of the giving of the Torah in tractate Shabbat on page 89a. And in this chapter of Psalms, I think it’s chapter thirty-seven, I’m actually not 100% sure, it describes Torah in three different ways. It calls Torah a shevi, which is something that is captured. It calls Torah something that is a lekicha, that’s a product that is bought. And it describes Torah as a matana, as a gift. So the question that many people ask is: Why is Torah being described in these three different ways? Is it a gift? Is it something you acquired and bought? Or is it something you captured? Those are three different things.

So a beautiful explanation that I heard, and I’m indebted to a rabbi of mine, Rabbi Dr. Ari Bergmann, who had a tremendous influence on my thought and approach, and I believe I heard this from him once, is that each of these descriptions of Torah relates to a different category of Torah. We have the written Torah. That is the written Torah, that’s the five books of Moses, the words of the prophets. That is a gift. We didn’t do anything to earn that, it just came to us. Then we have the oral law. That is the interpretation, the give and take. That’s what we, so to speak, purchase. We give of our own intellect, our own interpretation and we yield from it the body, the corpus of rabbinic law. That’s the interpretive part, that’s the lekicha [product]. It’s transactional, so to speak.

But then there’s a part that’s captured, and that is mysticism. Shevi is actually described, it’s the word shin, bet, yud as being an acronym for Shimon bar Yochai in this verse. Shimon bar Yochai, who is considered to be, I wouldn’t even call him the writer, the inspiration, the inspirational writer of the Zohar. Let’s call it like that.

And why is mysticism described as something that you capture? And I’m coming back to answer your question. It is because that’s the only way to create experience. What do we talk about when you, so to speak, freeze a moment in time? We literally call it, I want to capture this moment. Why do we call it capturing a moment, which is literally the word shevi? The way the Torah is described in this thirty-seventh chapter of Psalms is because time flows by back and forth. But sometimes you have a moment that is captured, something experiential that continues to animate your present.

So that was a story, it was otherworldly. It happened over twenty years ago, two decades ago, but that one line, I’m still learning that one line. I still don’t know if the beef and broccoli is in front of me, but that voice of Rabbi Moshe Weinberger sharing the words of Rabbi Tzadok, keshem she’adam tzarich lehaamin beHakadosh Baruch Hu, kach tzarich achar kach lehaamin be’atzmo [just as a person needs to believe in God, so too afterwards, you have to also believe in yourself], it is still reverberating in my life. That is the mystical lens to your own experience. That is shevi, that’s capturing a moment where the past and perhaps even the future can live in our very present.

LEVY: I think what’s so powerful is that yes, you came to capture it so to speak, but it really captured you.

BASHEVKIN. Very much so.

LEVY: It’s captured you and it still holds you in that way and you hold it. And that’s really the kinyan, that’s the acquisition that you have. And that really underscores the depth of that experience. And the specific sentence you decided to quote: First you believe in God, and just as you believe in God, then you believe in yourself. It’s almost like the God is the given, yourself is the journey. And therefore it sounds like the depth of your experience and your learning of that mysticism allows you to then believe in yourself in an even deeper way because by connecting yourself to something that is infinite, it allows you to realize the infinity that you are connected to.

BASHEVKIN. Self-knowledge and divine knowledge, which is what Rabbi Tzadok is talking about, really go hand in hand and they are iterative. And the same way that we can lose faith in God and almost believe that God does not exist, so to speak, God forbid, but we could – there are people who struggle with that. I think there are people who struggle with their own existence, with their own sense of purpose, with their own sense of uniqueness, with their own sense of, why am I alive? What was I put here for?

And I think that mysticism at its core is trying to wed those two. Even particularly Chasidut within mysticism, which is a branch of mystical interpretation, is really trying to wed the language with which we experience and discover and create a relationship with God, taking that language and using that very same language and process to realize that’s also how we ever are to learn about ourselves.

LEVY: So in an ideal world would all Jews be mystics?

BASHEVKIN. In some sense, yes, in some sense, no. In its broadest sense, which is not necessarily reading books of mysticism or even having a mystical disposition, you don’t have to dress differently. I’m fairly, I’m not clean shaven completely, but I don’t have a great long beard. In its broadest sense, mysticism is paying attention and interpreting your experiential life. To have that rich interiority, to have an internal life and an internal world that you pay attention to, yes, everyone should pay attention to their experiential lives. If you want to call that mysticism, I don’t think you’re wrong. I in fact think in its broadest sense that’s what it is. Then yes, everyone should be a mystic.

There is a very specific language of Jewish mysticism, a language of Kabbala, that language, I don’t think it needs to be known by everybody. For some people, it’s a language that you pick up on and it’s illuminating and eye-opening. There are some who never really discover what the language is trying to represent and convey. It could be confusing. I think you could be a very good, decent, spiritual, elevated Jew and not know the language of Jewish mysticism. I don’t think you need to know that.

LEVY: So, what do you think of when you think of God? It’s a very simple but a very deep question. What is God?

BASHEVKIN. So the word God is obviously a three-letter word. It’s an English word, G-O-D. That’s not what we’re talking about. I think you’re talking about what lies beyond the words. What do we try to represent with those words?

LEVY: Because that word is really a password and means something different to everyone.

BASHEVKIN. And there are different ways in which God is manifest in this world. God begins when you invest purposed, real, ontological – meaning that its very existence has purpose – to the material world. It’s almost easier for me to answer, what is a world without God? A world without God, I actually have a fairly easy time explaining. It is a material world that came about by accident. Your life is essentially an accident and you could convince yourself as a construct that it’s not. It is an accident. You’ve been, through evolution, been conditioned to love your own children, but honestly, if to have a true universal, altruistic approach, in a world without God, why should humanity have any superiority over the earth? It might make more sense to preserve the integrity of the environment and the earth for the entirety of humanity to be annihilated. Meaning, what’s the, we don’t really serve a purpose. There is no purpose to the world inherently, so it would be to me like, let’s say we found out that in one hundred years the world was going to get destroyed. I think that there’s a meaninglessness. People have the ability to create meaning without God of their own and convince themselves that – Like, I could find something, but they’re convincing themselves. It’s a construct.

God begins when meaning and purpose and what language is signifying is not just a construct. That’s why when people say God is love, what I think they really mean is the capacity for love as a real ontological reality that there’s something; love is something real. It’s not just a construct that a bunch of people agreed upon, but it really represents something, that there is a real conceptual world. That is what I think God gives this lived experience.

LEVY: So is there an experience or a feeling or an image that comes to mind when we say God? When you’re praying to this, is there any sort of –

BASHEVKIN. I think it’s not an image, it is a capacity. To me, when I think about God, it is the capacity, it is the urge, it is the instinct to pray. If you’ve ever felt that instinct, I’m not talking about somebody who’s praying three times a day in a Jewish minyan, no. Anybody who’s ever felt the instinct to reach beyond, anybody who has looked up and said, I need help, I don’t know why I’m here, who felt the angst of purpose, of alienation. That is where God begins.

LEVY: So it’s almost like a feeling, like there’s an experience that is synonymous with that word God.

BASHEVKIN. But I think more than a feeling, I think it is a capacity. It’s an instinctive capacity that we have within our lives. An instinctive capacity to want to give, to want to love, to want to be loved. Nobody has ever looked in the eyes of their wife or their children and didn’t believe in God with real love. They weren’t thinking, oh, this universe is an accident, I happen to love you. It’s just neurons firing. That’s a very reductionist materialist approach. It actually is a very coherent approach. I understand it.

To me, the layers of interpretation almost parallel the different dispositions and religious ideas of the world. To phrase it quickly, we have four levels of interpretation. We have peshat, which is the plain meaning of the text. We have remez, which is the allusion to the text. We have derash, which is the deep investigative interpretation, and then we have sod, which is experiential, which is the purely experiential world. I believe, and those four are colloquially sometimes called by their acronym, peshat, remez, derash, sod as Pardes, which means a garden, and it’s referred to when the Talmud sometimes speaks about Jewish mysticism. It says entering the garden. It’s going to the deepest layers of interpretation.

But to me, a plain reading of the universe is an atheistic reading. It’s just looking at the universe as a self-sufficient materialistic body. But you have to be honest about it. What is a world without God? Then love is a construct, language, everything is a construct, meaning is a construct, and it’s all just trying to distract ourselves until death and then oblivion. So I don’t know, why even wait till then? Life, if you’re a very radically honest atheist, it is a hard world to live in.

LEVY: So then where do the Jewish People fit in? We’ve had conversations about [how your] mission in life, and I think you’re doing a phenomenal job of it, is to really know the Jewish People and to be someone that really believes in those people. What is the purpose of the Jewish People?

BASHEVKIN. That’s an excellent question. The purpose of the Jewish People really begins with the founding of the Jewish People and how the Jewish People were ultimately structured. The Jewish people are founded not by prophets, not by rabbis, that’s not what we call the founders of Judaism. We call the founders of Judaism avot and imahot, which means mothers and fathers. That’s the founders of Judaism. Judaism is designed deliberately in a familial way. Meaning, Jewish identity is unearned. I did not do anything to earn my Jewish identity. I was born into it. Even a convert who chooses to become Jewish, once they make that decision, it is irrevocable, like Hotel California, there’s only doors in, there’s no checking out.

When it comes to the purpose of the Jewish People, the question is why are we structured this way? Which I think will get to our purpose for the wider world. Why are we structured this way? If Judaism’s purpose was to be just a light unto the nation, so to speak, by how wonderful we are, then Jewish identity should be structured in a way where the only people who are considered Jewish are the righteous or the good ones. And we may have different definitions of who the good ones are. You know, the good ones are the people I like, good ones are the people you like, but that’s not how Judaism was structured.

So one would think if you were starting a religion, you would start the religion and you’d include the people who are committed to the religion, who are doing it correctly, who really are passionate about it, whatever your metric is. That is not how Judaism is structured. The entire story of the book of Genesis is the creation of an immutable familial identity as the heart of Judaism. That is structured through the avot, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and the imahot, which is Sarah, Rivka, Rachel, Leah. And their children who become the twelve tribes form the bedrock of the Jewish people. But the identity is unearned. So why is Judaism structured in this way?

I believe Judaism is structured deliberately as an unchosen identity as a message to ourselves and the world to learning how to contend and build and find meaning with our unchosen roots, with the part that came, that preceded us that we had no power over. Because what are we trying to show the world? The ultimate unchosen identity is not Jewish identity. The ultimate unchosen identity is existence itself. Nobody chooses to be alive. Nobody chooses to become conscious. I don’t even remember when I became conscious. Most people don’t remember. You have earliest memories, but there’s not like a moment where you’re like, oh, okay. It’s unchosen. Existence itself is unchosen.

What the Jewish People represent and what we are supposed to teach the world is how to grapple with our unchosen identity. The ultimate unchosen identity is existence itself, and we are a model to the world for how to sanctify unchosen identity, which essentially, in its most essential part, is life itself, is existence itself.

LEVY: So our purpose is to allow others to see that?

BASHEVKIN. Our purpose to the world.

LEVY: Yes.

BASHEVKIN. Our purpose for ourselves is to sanctify our unchosen identity, which is our Jewish identity. What does that teach? That’s learning how to sanctify existence, how to sanctify life itself.

LEVY: And our purpose for the world is to teach others to do that?

BASHEVKIN. Absolutely.

LEVY: Or by us doing it for ourselves, that’s enough?

BASHEVKIN. No, I think we are meant to teach the world how to live and embrace their unchosen identity, existence itself.

LEVY: Amazing.

BASHEVKIN. I think we have a very real message to tell the world. Everyone is grappling with the hyper-local experience of being Jewish. The whole world is not Jewish and the whole world is not meant to be Jewish. But the whole world is grappling and trying to figure out: How do I make meaning and sense and purpose out of an identity that I did not choose? What’s that identity? For us it’s Jewish identity. But on a deeper level, what we’re modeling for the world is existence, is the ultimate unchosen identity. How do you sanctify it? How do you find meaning and purpose in it? That’s what we are doing ourselves and hopefully modeling for the world.

LEVY: So is the answer to that question the 613 mitzvot, which are different paths in different categories and areas to be able to –

BASHEVKIN. Is contending with commandedness. Yes. Contending with commandedness.

LEVY: Well, there are even pathways to be able to sanctify that.

BASHEVKIN. Sure, and there are different ways and different people are going to have different relationships with commandedness. But I think our purpose is teaching people the very notion of commandedness. The very notion that there is a purpose. There is a way to live. There is a way to find nourishment and spiritual meaning in life. And that is what commandedness in its deepest sense is. It’s that almost deepest, most essential type of urgency of how you should be living life.

LEVY: Amazing. So how does prayer work from a mystical perspective?

BASHEVKIN. That’s a very, very serious and complex question that I’m not sure I am – I’m still trying to figure out in a lot of ways how prayer works. My difficulty with prayer – and I think most people’s difficulty with prayer – is when they realize that what we pray for more often than not does not come true, is not manifest. I mean, we’ve all seen tragedies happen. We’ve all had sick people that we are praying for to get better. We’ve all had loss. We’ve all had things where we’re going to storm the heavens and we’re going to ask for it and it’s going to come and then it doesn’t come and that disappointment can be religiously heartbreaking.

I know it was heartbreaking for me at a point in my life. I have memories of me alone in a classroom reciting Tehillim [Psalms], waiting for God’s answer. And the response that sometimes God says no, it does not fill me up, and it never filled me up because it sounds like it’s usually no. So maybe what prayer is is not even asking for a yes or no. I think prayer is, more than anything, a chance to be in a relationship with something beyond you. I think prayer is an experiential reminder to ourselves that there is a purpose that lies beyond us. And there’s a deep, deep comfort and it should shape us.

I actually think the ultimate prayer and the ultimate model of prayer is what’s oftentimes spoken about in AA groups, what’s known as the Serenity Prayer. And I actually was an intern once for an organization that helped Jewish alcoholics and substance abusers and their families called JACS. So I have merited to be inside of the room at AA meetings. And the Serenity Prayer says: Lord, give me the strength to change the things that I can, give me the serenity to accept the things that I cannot, and give me the wisdom to know the difference. The first thing we pray for in our daily Shemoneh Esrei, which are the blessings that we say in direct communication, in direct confrontation, so to speak, with God, the first thing we request and ask for is that wisdom to know the difference, is the wisdom to know what is within our power, is that prayer is not a retreat from action. Prayer is not a retreat from agency and independence and choice and decision-making. I think prayer is that internal space where we actually grapple with the limitations of our agency and our ultimate dependentness on something that lies beyond us.

And I think that the Serenity Prayer, in three lines, in many ways captures what I think with much more mystical foundations and illusions and language is ultimately what prayer is trying to accomplish. To give us the strength to change the things that we can, to give us the serenity to accept the things that we cannot. There are things in our lives that are never going to change. You could pray for them from here to the day you die, it’s never going to change. Part of prayer is asking for that serenity to accept the things that you cannot.

And of course, at the heart of prayer is that grappling, is the wisdom to know the difference. God, I don’t know where I end and You begin. I don’t know where, I don’t know what my capacity is. I don’t know what I should even be trying to change sometimes.

Rabbi Tzadok’s rabbi was Rabbi Simcha Bunim of Pshischa. And he says the ultimate form of prayer is what David Hamelech says, King David says in Psalms, ve’ani tefilla. I myself am the prayer. The illusion that Rabbi Simcha Bunim gives to talk about prayer is sometimes you hear a knock on the door and there’s somebody dressed in a suit and they want a meeting with you, and they pull out a nice pamphlet, and they talk about their nonprofit and their cause and what they’re doing, and you can decide to give money and you can decide not to give money.

Sometimes you hear a knock at the door, you open the door and you see somebody who’s broken, clothes are ripped, they look dirty and just forlorn and hopeless. You don’t ask that person, do you have a brochure? You don’t ask that person. That person themselves is coming before you with that brokenness. And I think that prayer is an opportunity to come before God completely. Meister Eckhart says: It is the same eye with which I see God that’s the same eye that God sees me. And what I think prayer is is an opportunity to bring the entirety of yourself, all those hidden parts, all that disappointment, all that everything, the entirety of self, and bring it to something transcendent, to something that is beyond.

And sometimes you don’t even need the brochure. That itself is the prayer.

LEVY: Bringing those two together, ve’ani tefillati, I am my prayer. It could be saying that not just I am my prayer, but my I is my prayer.

BASHEVKIN. Yes. Yes.

LEVY: If you bring that together in that sense. But I think what you’re saying, which is very deep, is often when we communicate. The purpose of this communication, one would think, is for you to be able to understand what I’m trying to say and what I’m trying to give across.

So prayer is a method of communication where it’s a medium to get across a message. But the message may be reversed in the sense that prayer is actually a medium for a relationship.

BASHEVKIN: Correct.

LEVY: The words aren’t like – if it’s going to be a yes or no at the end, it isn’t even as important as the capacity to be able to say something.

BASHEVKIN. Yes, yes.

LEVY: And then where does it put Torah study? What is the goal of Torah study?

BASHEVKIN. I think the goal of Torah study is taking our interpretive abilities of our own experiential lives and reading and connecting to the dictates of the Torah and mitzvot. Again, this is pure Torah study, pure Torah study and using our interpretive abilities to find resonance and find ourselves in God’s words and the words of the Torah and the Sages that have come after them.

LEVY: So in that process, does Jewish mysticism view women and men as the same?

BASHEVKIN. I think the answer has to be no, but for a different reason. I think what mysticism is basically trying to do is develop a language where the conceptual is more real than the material. It is trying to give you the conceptual underpinnings to the material world. So men and women are different in the material world. They’re different biologically, they sometimes have different aptitudes and different, you know, there are differences between men and women and you can read, whether it’s a psychologist or a biologist or any doctor talking about the many, many differences between men and women.

I think that what mysticism focuses on is not on biological differences but the conceptual energies that are differentiated that are oftentimes manifest within genders, but what do those gender differences represent? And I think that we do sometimes use the language of gender differences that is not trying to make a distinction that all men are this way and all women are that way. Rather, it’s trying to say the ultimate differentiations that we see through gender, what does that conceptually represent spiritually in terms of the way the world works? And I think that that difference very much is present throughout Kabbala, specifically the capacity and the desire to give and the desire to receive. And talking about how to unite those two powers, which is the masculine and the feminine power, which doesn’t mean that every woman is purely a receiver and every man is purely a giver. But conceptually, we have two different forms of energy. I’m speaking very broadly, that I think what Jewish mysticism privileges is the conceptual differences that are manifest in much different ways biologically.

LEVY: One of your roles is really to help youth come into Judaism and to connect in so many different ways. When you look at that kind of person that’s coming in, is Judaism meant to be hard or is Judaism meant to be easy?

BASHEVKIN. I love that question. My instinctive answer is easy, but I would rephrase what I mean by easy. Judaism is meant to fit into your life. Our entirety, our entire sense of self is a container, is a vehicle for the divine, and it is meant for divine expression. We’re not trying to stamp out or to eradicate our personality and all of our quirks and differences and sense of humor or character. That’s what was being informed and being filled up by the relationship with the divine.

So I think that Judaism is meant to fit into our lives. I think very often when you see people who are struggling with religious life, with Jewish life, it’s usually because they have too much or too little, and both are possible. It’s possible to have an unhealthy relationship with Jewish commitment, with Jewish law, with halacha, with mitzvot. You’re so nervous, so anxious, so inorganic, you’re not able to converse and have healthy relationships with those around you. That’s too much. And sometimes there are people who have too little. It’s so watered down, it’s so inconsistent, it’s so nonsubstantive that it doesn’t nourish them. It’s like, it becomes like a piece of candy. Like, yeah, have a piece of licorice every once in a while. Doesn’t really fill me up. I want real stuff, you know, and that – Judaism doesn’t seem that way to a lot of people.

So whether it’s hard or easy, the Torah itself calls it something that is exceedingly close to you. It is not hard. It is not in the heavens, lo bashamayim hi. It is not in the heavens. It is karov eilecha, it is very, very close to you. So in that sense, I think Judaism should be easy, not that it doesn’t require sacrifice or commitment, but the ease should be that it fits your life. It fits who you are. It should fill you up completely that your Yiddishkeit and your very sense of self, it doesn’t feel like something extraneous. It feels organically intermeshed with your very sense of self and very personality.

LEVY: So stepping back out for a second, God put us in this world, we’re meant to fit these things together, but why did God actually create the world?

BASHEVKIN. The first person who I think developed a real theology directly trying to answer this question was Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto, the Ramchal. And I think the way that it is ultimately described is, God created the world in order to give, in order to have an other, in order to bestow, because the ultimate good is the good that comes from giving. And God created the world, the capacity that animates. The desire that animates the entire world is the desire to contribute, is the desire to feel needed, to feel purposeful.

And I believe that is because that is the ultimate underlying purpose of the world. The purpose of the world was to create purpose. There’s no purpose if it was just God in the world. So the creation of the world, so to speak, was the creation of something other that there can be a giver, and it’s that very created – it’s that very purpose that underlies the purpose of our lives as well.

LEVY: Meaning if we’re meant to emulate God –

BASHEVKIN. Exactly.

LEVY: And God created with purpose, therefore we should create purpose and connect to purpose.

BASHEVKIN. Exactly. Purpose, purpose, purpose. Finding meaning comes from being purposeful, having impact in others’ lives. Yes.

LEVY: It’s good. He did it on purpose. But the question then is, once He’s created that and we’re meant to emulate that, do we have a choice in that emulation? In other words, can we do something against God’s will?

BASHEVKIN. In this world I would say there are two levels to the way we talk about God’s will. There is the transcendent notion, the all-encompassing infinite expression of God that encompasses everything, where everything is ultimately a reflection of God’s will. That certainly exists within Judaism. That’s most notably expressed within the school of thought of Rabbi Tzadok, where Rabbi Tzadok says, hakol beyidei shamayim, everything is in the hands of heaven, afilu, even, and he’s playing off a line of Talmud, reversing it. The Talmud says, everything is in the hands of heaven except your fear of heaven, except your sense of closeness to God. That’s in your hands. And Rabbi Tzadok reverses that line of Talmud based on the teaching of his rabbi, known as the Izhbitzer, Rabbi Mordechai Yosef Leiner, and says, even that, even your closeness to God, even your religious personality, that’s also from God. That is a very transcendent level that we would call an approach that minimizes free will, where it’s a very, what we call deterministic view. That certainly exists.

On the other hand, we also very much privilege, not only privilege, but we insist that this world is deliberately created with a very real sensation, it’s not just a sensation, with the very real capacity to choose. Leaning into our choice, using our choice to actually confront what’s beyond our choice, I think is the ultimate answer.

Both perspectives are true. The deterministic perspective and the perspective of free will and agency both coexist. It is the ultimate paradox of existence itself. I think it parallels in many ways the two readings of the seven days of creation. When the Torah opens up, it opens up with seven days of creation. The last day being Shabbat. So there are six days of creation and then there is Shabbat. In the third chapter of Genesis we have the story of the sin of Adam, right? Of Adam’s sin. So the question is, when did that take place? Did Adam sin and the kind of deterioration of humanity’s closeness to God, did that happen as a part of creation or did that happen after creation? And that tension we see in the text itself. The text is ambiguous. It’s unclear when.

LEVY: Meaning it could have happened in week two or it could have happened on day six?

BASHEVKIN. It depends how you read it. A plain reading of the text, I would suggest, is that it happened after creation, is that God created the world in six days and then rested on Shabbat, and then we are introduced to the story of man corrupting God’s perfect world. That’s actually the Christian view of creation. The Jewish view holds both simultaneously. We have the plain meaning of the text, but we also have the Talmudic interpretation, where the Talmudic interpretation deliberately places the sin of Adam as a part of creation. That is significant because it means that there is a perspective in which failure itself, sin itself, distance itself, alienation itself is also a part of creation. It’s also that deliberate manifestation of God.

So both exist. We live in a world that requires us, that demands of us, to exercise our free will. But our free will has capacity, has limitations, and there is a perspective that exists simultaneously, that even what lies beyond our will, even our free will itself are all reflections of God.

LEVY: Just to unpack one part of what you said. You’re saying that essentially the capacity to sin did not just happen, it was part of the fabric of creation and therefore God willed the sin to happen so to speak.

BASHEVKIN. That’s the Talmudic reading. The Talmudic reading deliberately dates the sin of Adam that it took place on the sixth day of creation before Shabbat. And that when God on the sixth day of creation looked at the world and said it was very good, that was actually God’s acknowledgment of the existence of subjective evil in the world. The capacity to see something that’s not just good or bad but that something can be very good is where subjectivity, which is that subjective approach to the world, was really born through the sin of Adam eating from the tree of knowledge.

LEVY: Yeah, another interpretation could be it’s very good that humanity decided to do something for itself. Meaning that God created that space for us to co-create and then we took action. Whether or not that action was good or bad, the fact that we took action could have been very good in God’s eyes.

BASHEVKIN. Yes, but how [should we] interpret that “very good” of the sixth day? Why is God all of a sudden calling it very good? I think you get to both of these perspectives: the deterministic one and one that’s more couched in free will.

LEVY: Yeah, well I mean if the purpose of creation, according to the Ramchal that you quoted, is to be able to give and the ultimate expression of giving is giving someone the capacity to do something on their own, then when He saw them do something on their own, that’s very good.

BASHEVKIN. Exactly. Exactly. Exactly.

LEVY: So what about, part of our mission is to rectify that original sin, is to come to a better time, what we call Mashiach, the Messianic Era. What do you think of when you think of Mashiach?

BASHEVKIN. There are three stages to the world in my opinion. The first stage is the creation of the world. And God creates the world through a Hebrew verb. He doesn’t create it through words of action. The way we talk about God’s act of creation is vayomer, which means and he spoke and he said. In fact, the Mishna in Pirkei Avot [Ethics of the Fathers] in the fifth chapter says that there were ten maamarot, ten sayings that created the world. So the world was created with ten sayings. The Torah, when God gave the Torah, the Torah describes them as dibrot, which also is a word of language, which means and God spoke out, but it’s a different form of language. We’ll get to what that difference is. Then finally, there is the word Mashiach.

Mashiach, Rabbi Tzadok writes in Divrei Sofrim in the sixteenth paragraph, Rabbi Tzadok says that despair, the Hebrew word – stay with me – but the Hebrew word for despair is 317. The Hebrew word for despair is yeush. If you add up the numerical value, what’s known as gematria, of each letter, yud, vav, alef, shin, it’s 317. To transcend despair, says Rabbi Tzadok in this very important seminal paragraph, this sixteenth paragraph in Divrei Sofrim, he says to transcend despair is 318, which is the word siach. Siach is also a word for language. The word mashiach is meisiach, coming from the place of siach.

So that’s very interesting, let’s stop for a moment. God creates the world with the word vayomer [and He said]. Then He creates the Torah, so to speak, with the word vayedaber [and He spoke]. And redemption ultimately comes through siach [conversation]. What are the differences? Why are they all words for language? So I’ll try to say it as succinctly as possible.

The word vayomer versus vayedaber is the difference between – you ever teach a class?

LEVY: Once or twice.

BASHEVKIN. So, what happens when you throw out a question to the audience? You have a make-believe audience over here. So I go to the make-believe audience and I say, what’s the difference between vayomer and vayedaber? They’re both words that sound – and He spoke. What’s the difference? What’s going to happen with the class? What are they going to do?

LEVY: Well, we learned together the, like –

BASHEVKIN. Oh, don’t ruin the ending. This guy is ridiculous. I can’t even deal with him.

LEVY: They’re going to be chucking out different ideas. Or they’re going to be dead quiet.

David Bashevking: Usually, honestly, they’re going to stay quiet. No one’s going to really respond. They’ll be like, I don’t know, and they’ll be quiet for a few seconds. Maybe one Goody Two-shoes will raise their hand and say it’s me. But everything changes if you call on one kid and say, Josh, what’s the difference between vayomer and vayedaber? All of a sudden, Josh.

LEVY: If you’re compelled to say something.

BASHEVKIN. He needs to say something because he was called upon. That is the difference between vayomer and vayedaber. Vayomer is throwing out a question that you don’t necessarily have to answer. You’re not being addressed personally. It is what you have the capacity to feel. Vayedaber is where you are confronted, not just with a question, you’re being confronted by a speaker. That’s why the word dover, a speaker, is conjugated specifically from the word vayedaber. It’s when I say, Josh, Sarah, Rachel, you know, you call on somebody, that’s where you’re confronted. You in your life are being called upon.

That is the world of Torah, right? We live in that world of Torah. The problem is when we live in that world of Torah, which is not the world of what you can feel, that’s the creation of the world. That is what’s out there. You can respond, you cannot respond. Torah is the world of what you should feel, how you should be living. You’re confronted by somebody, and you feel like, and you know what happens in that world? You try to live that way, but you know what happens? You mess up, and you fall apart, and you feel shame, and you feel guilt, and everything is a mess.

And ultimately you can, often times, despair, and you can say, I messed up. This is not, this is, this is not, this is not working out. You start to stop believing in your own life, in the purpose of your own life, your ability to find meaning in your own life. When you’re not able to reach and respond properly to that world of vayedaber, of the Ten Commandments, of what you should feel, you end up with all of this brokenness, all the shame, all the feeling that a lot of Jews, all Jews I think, carry to some degree.

That is what I think about when I think of Mashiach. Mashiach comes from the world of siach. Siach is not what you can feel, the world of creation of the world. It is not what you should feel, which is the speech of the Torah. It is what you feel. It is learning how to find redemptive experience in your actual life where you are right now and saying that I can find redemption in my own present life. Mashiach is that redemptive idea that comes from that place of siach. That’s a non-hierarchical conversation. Not you know more than me, I know more than you, but in the presence of my life, where I am right now, with all of the imperfections, with all of the things that I should be doing and I’m not, with all of the things that I’m reaching for and don’t yet have, being able to find wholeness and completeness and divinity and spiritual nourishment in that place, that is the Messianic impulse that animates the entire world. That is the redemptive impulse that’s been flashing since the creation of the world, and that is the individual notion of Mashiach, of being able to find that wholeness and that enoughness in your own individual life.

There is a collective vision of Mashiach, which is when the entire world is able to reach that place, where we’re able to see it in one another and through one another. Where we’re able to see in the right here, right now, Mashiach, that redemption. I don’t think anything’s going to change in the world except a genuine certainty of being able to live our lives with a purpose, with a Godly purpose. Nothing else is going to change. It’s taking life seriously and realizing that we’re living our lives not as if God created the world but really looking at ourselves as creation. We are creations, and we were created with a purpose, and that is life itself. And when we learn how to embrace that in a redemptive way on a collective level, how to run societies based on that, that I believe is the collective revelation of redemption and the Messiah.

LEVY: It’s beautiful because the Talmud famously says, we learned it together, the Talmud in Brachot, ein sicha ela tefilla [conversation means nothing other than prayer].

BASHEVKIN. Yeah.

LEVY: That this term of siach, sicha, this conversation, this dialogue, is prayer. And it ties beautifully to that element of prayer, how you said before, itself, and coming together.

BASHEVKIN. Yes, yes.

LEVY: You also said meisiach is meh, mem, meaning from.

BASHEVKIN. From, exactly.

LEVY: But from a grammatical construct perspective, we refer to mem as the mem performative. It’s used in the hifil [grammatical] construct.

BASHEVKIN. Yes.

LEVY: So meisiach means the one that is creating siach, the one that is really creating the synchronicity. So maybe that Messianic Era brings about this consciousness where we all have that alignment and that synchronicity.

BASHEVKIN. Right. Well, Rabbi Tzadok writes explicitly in Tzidkat HaTzadik, I don’t remember the exact paragraph, it might be 117, but I’m pretty sure I’m incorrect on that. But Rabbi Tzadok does write in Tzidkat HaTzadik that every single person is born with the capacity to be someone’s Mashiach. Meaning, instead of waiting for Mashiach, become a Mashiach, become someone else’s Mashiach, become someone else’s savior, help somebody else. If everybody spent their time trying to be somebody else’s Mashiach, trying to bring out that power of siach and help people find meaning and purpose in their lives, ultimately I think that collective redemption would be revealed.

LEVY: Well, we’d all experience Mashiach for someone else.

BASHEVKIN. God willing.

LEVY: So is the State of Israel part of the final redemption?

BASHEVKIN. I certainly hope so. I think the State of Israel, the seminal question that we are still trying to figure out is how to run a Jewish state. How should the ideas that have preserved the Jewish People, the actions, the commitments, Torah and mitzvot, how can we run a state based on that? It is almost a very logistical plain question, but I think it’s the question that at the other end of it lies that collective redemption where Israel can be a model for the entirety of the world of how to preserve, to come back to our earlier question, how to preserve that unchosen identity and find meaning from it.

We could be a model for all countries, for how to preserve a culture, how to welcome in others, how to live in peaceful coexistence with others. We should be the model for this, how to preserve Yiddishkeit and religion without coercion. I don’t think that the ultimate redemption is necessarily, like, bringing back and murdering people for violating Shabbat. I genuinely don’t. I believe that the ultimate question, the final frontier that we have in order to make the State of Israel as a part of redemption. Meaning, the answer to your question ultimately is that’s on us. We can decide to make the State of Israel a final part of redemption.

LEVY: So when you say you certainly hope so, that means from God’s part it seems like it is. But now if our job according to Rabbi Tzadok is to be the Mashiach for everyone else, then by doing that we can create this ideal state.

BASHEVKIN. I am a believer in Maimonides, the Rambam. And he talks about the Messianic Era with some ambiguities. We try not to go into it too much, but one thing the Rambam is very definitive about is that it is not the return of open miracles. It is not a time where all of a sudden we’re going to have the world upside down. It is happening in this world. in this world right now. So how could I not want to daven that the Jewish state that we have control of, as imperfect as it may be, should not be a part of the final redemption? What’s your plan B? I mean, we have it. It seems like a jaw-dropping lack of gratitude and a willful misrepresentation of Jewish history to not think that it could play a role. But in order for it to be that role, it’s going –

LEVY: We need to play our role.

BASHEVKIN. It’s going to require the participation of the entirety of the Jewish People. We need to figure this out. Everything that we’re fighting about, on the other end, if we ever learn an answer for how to address all the controversy, you could fill in, you probably have five going through your head right now. The other side of that question is the answer that ultimately is – that is the collective redemption. That is us serving as a model for the world of how to preserve a people, how to preserve a family, how to live together in society as families and ultimately as one family of humanity.

LEVY: So if it’s there to be that light and if we universalize it, going to the broader world, what would you say is the greatest challenge facing the world today?

BASHEVKIN. I think our greatest challenge, the greatest challenge facing the world today is that we stopped believing that there could even be a purpose to existence itself. People stopped asking or really thinking in serious ways about spirituality on a mass scale. I think that the biggest problem with the world is that we act as if it is purposeless and we try to find meaning in the most ridiculous places, whether it’s, I don’t know, politics, sports. I’m not anti-sports, I’m not anti-politics. I think they are both really really integral, but we act as if we are not spiritual beings.

It’s like, could you imagine, there are all these shows and movies about people who are stranded on deserted islands. They don’t waste one day trying to figure out: How do I get off here? How did I get here? How do I survive here? How do I find meaning here? And for much of human history, we were still asking that question, which is: How did we get here? What are we meant to do with our lives? And there was a time where the greatest minds in the world were solely focused on these questions. And they spoke about spirituality, they spoke about transcendence. Serious people.

And I think that part of the tragedy of modernity is that we stop taking those questions seriously, is that we think the answer to our questions is in HR departments and in corporate governance and in political oversight. Yeah, those are all good things. None of these is going to give us the roadmap for existence itself. We each have a limited amount of time on this world, on this earth, and we still have no idea what we’re supposed to do with our lives. We’ve made very little progress over the last 200 years in figuring this out with all of modernity, all of technology, all of the medical advances that we’ve made. We’re still kind of distracted – willfully ignorant of how short our lives are on earth and how little we appreciate just that underlying – what is the purpose of this?

LEVY: I think the willful ignorance comes from that distraction, meaning that we don’t stop to think as much because we fill it with all those different kinds of things.

BASHEVKIN. Yeah, it’s much easier to scroll.

LEVY: Doomscrolling, but even the politics and the sport and everything. So I don’t have time to sit and reflect and have those deep conversations in an essentialist or existential way.

BASHEVKIN. I think society is genuinely traumatized that they have no idea why they are alive. I think there are people who are unable to admit that or they have sufficiently distracted themselves from that question. And I think that is the greatest challenge facing humanity, for us to wake up from our collective slumber, realize that we are alive, and figure out what we are supposed to do with this short time on this earth.

LEVY: But I think it’s a choice, meaning that you – we use the word willful, the willful ignorance. I think we choose to distract, meaning someone says, how am I going to fill my time? What am I going to do? So I’m actually filling that because part of it may be because it’s such a hard question, part of it may be for the fear of the answer, and part of it may be that we don’t have the capacity or capability to grapple with it because we’ve trained ourselves to have something else tell me what’s going on.

BASHEVKIN. Yeah, it bothers me a great deal that, especially since October 7, with the headlines all about Israel and the Middle East and all this stuff, I’m saying the world has very little understanding and does not take religion seriously. And I think that if the world examined and understood Judaism, Islam, Christianity, what these forces represent to the world, what is our vision collectively together? How do we get all of us closer? I think we would be in much better shape. But the language that we’ve become so used to is the language of modernity, which is much more political, which is much more technical, much more capitalistic, much more about money. And all of us are in a slumber in our lives, which is why anybody who has confronted death – it’s a wake-up call. You wake up to life.

LEVY: So you talked about the language of modernity and how it’s had these effects. And in a sense, you said that it’s almost a disappointment that with this advancement, with modernity, we haven’t really got that much further on the answer to that question. What has modernity done for Jewish mysticism? Or how has modernity changed Jewish mysticism?

BASHEVKIN. I think modernity has revolutionized Jewish mysticism. As you know, I have –

LEVY: 18Forty.

BASHEVKIN. 18Forty. I was hoping you were going to go there. Yeah. As you know, the media site that I run is called 18Forty, and the reason why it is called 18Forty is named after the Hebrew calendaric year of Tav Resh, which was the year on the Hebrew calendar of 1839–1840. And in that year, the significance of that year is that it was the end of the sixth century of the sixth millennium. And that year, the Zohar says, the lower waters are going to open up and they’re going to fill up the earth with wisdom and knowledge of the divine.

So in the year 1840 there was actually a great Messianic awakening. And that was also the year that if you look just in terms of what was happening in the world, the industrial revolution, it was a year of great modernity. There’s a great book by Orlando Figes called The Europeans, which focuses exclusively on the 1840s and how the world was changing during that decade.

I named 18Forty specifically after this year because during that debate of that Messianic awakening, so as you know, there is no figure called Mashiach who came in the year 1840. There was actually a debate. There were people on, let’s say, more in the right-wing, traditional, conservative part of the Jewish community who actually blamed the fact that Mashiach did not come on technology, they blamed modernity. You know, that is something rabbis have done throughout the generations, blame what the kids are into, and it was better in my years, and we didn’t look at the video games, and we didn’t look at the internet and social media. And they blamed whatever was going on in those days – modernity prevented the Messiah.

And then there were others on the very radical left wing, some Reform thinkers, who literally looked at modernity and said, that is the Messiah. This is it. This is the Messiah coming. We can live nice, comfortable lives. We have telegraphs and locomotives and the world is globalizing and becoming smaller. This is what the Messianic Era is.

There was a middle path that was charted by Rabbi Tzadok’s rabbi, who I told you we’d be coming back to a few times. Rabbi Tzadok’s rabbi, the Izhbitzer, Rabbi Mordechai Yosef Leiner, began his Hasidic movement on Simchat Torah of Tav Resh in that year of 1840. That’s when he broke off from the Kotzk movement of Hasidism and he started his own Hasidic movement. His Hasidic movement was actually a reinterpretation of what those lower waters can actually yield. It was that modernity actually allows us to ask redemptive questions. Modernity frees us up to look at our lives in new ways. If you lived 700 years ago, what choices were at your disposal? What abilities did you have? Your identity was very much baked in. A lot of what modernity has offered us is the world of choice, of really building lives as we see fit, as we wish. And modernity gives us more and more options and optionality.

What mysticism allows you to do is to find order, to find unity in that divisiveness, in that world of chaos of modernity. And mysticism has had an explosion but specifically from the lower waters. It’s been very bottom up. The movement of mysticism is not just from the top down, this is what you should think, this is what you should feel. The ultimate movement is one that can be addressed from the lower waters, a bottom up movement, an organic awakening where society realizes that the only way forward is to start asking the real questions. The only way forward, the only real progress to move society forward is to figure out the most essential questions, which is the meaning of life, the purpose of life, et cetera, et cetera. So I think modernity in many ways – and I’ve built the entirety of 18Forty on this very premise – is that modernity accelerates our engagement with mysticism and deepens our need for mysticism, the urgency of mysticism.

The relationship of modernity to mysticism is similar in many ways to the relationship of modernity to Shabbat. Is Shabbat more – is it harder in modern times or easier? It’s become much harder to keep Shabbat in modern times, much harder. So many more distractions, there are so many things that you can’t do. 700 years ago there was no option to drive or turn on lights. It’s much harder nowadays in many ways. But the urgency of Shabbat is so much more needed. The outside world looks at Shabbat observant communities with a rightful state of envy. We are preserving the very purpose of life itself, the ability to be, the ability to find meaning in existence itself. And that to me is what mysticism is all about and both of them, I think, are intimately connected to modernity.

LEVY: So what differentiates Jewish mysticism from other forms of mysticism in other religions?

BASHEVKIN. That’s a really, really, really complex question because it relates to different definitions of where Jewish mysticism ends and where other forms of mysticism begin and also the interplay specifically between Christian mysticism and Jewish mysticism, who were very much in dialogue with one another.

There was a scholar named Christian Knorr von Rosenroth who translated the Zohar and many mystical texts into Latin that ended up really revolutionizing thought and modernity. The work he put out was called the Kabbala Denudata. He was in dialogue with Leibniz and with Newton and John Locke and this whole circle. Not Christian Knorr von Rosenroth, but the people who were around circulating his ideas, most notably Francis Mercury van Helmont, who was the person who went around selling this kabbalistic text. There is a writer named Allison Coudert who talks about what the attraction specifically of Jewish mysticism was to all of these thinkers as opposed to Christian mysticism. And there is a real Christian mysticism. I quoted earlier Meister Eckhart, who I believe was a great Christian mystic and really has had some profound ideas, but Jewish mysticism, I believe, is something very, very unique and it relates to how we see and understand redemption.

Essentially, what Allison Coudert writes, and I think it’s absolutely true, is that the unique contribution of Jewish mysticism is that the Jewish view of redemption, of rectification, is not to capture a forfeited past but to create a more perfect future. The Christian view of original sin, the Christian view of the creation story dates, as I mentioned, the sin of Adam to after the creation story. So God created a perfect world, man corrupted it, and now we have to go back to God’s perfect world. We’re trying to restore something.

The Jewish view is much more proactive and requires the actual participation and agency of humanity, of the people. That is where humanity’s purpose is to perfect the world. Perfection is not seen as a forfeited past but it is the future state that it is upon us to create and bring to the world itself. I think at the heart of Jewish mysticism is this emphasis on agency and our need to create that actual future.

I think that is at the heart of Jewish mysticism. And I think in many ways [that is] what differentiates it from [Christian mysticism] and what attracted many Christian thinkers to that Jewish idea as articulated through mystical texts, most notably the school of thought of the Arizal. And you could read about that. Allison Coudert has the book, it’s called The Influence of Kabbalah on the Scientific Revolution. Happens to cost a fortune, but I did interview her. She’s a fascinating, fascinating thinker and it’s a fascinating work. It’s a fascinating lens to think about the interplay.

One of the ways in which I conceptualize different mystical approaches to different schools of religious thought on mysticism is through the Pardes concept that we spoke about earlier. There’s a concept called Pardes, which means that there are four levels of interpretation. There is the peshat, which is the plain meaning, the remez, which is the allusion, derash, which is the investigative meaning, and then there is the –

LEVY: Sod.

BASHEVKIN. Sod, which is the experiential meaning. To me, and this is my own approach and my own conceptualization, the peshat reading of the world is atheistic. It’s the word reading the world, so to speak, as a text but only looking at what’s plainly stated in front of you. To me, the peshat of the world, the plain meaning of the text, is an atheistic, materialistic world.

Then we have an illusionary text, the remez. I think this is the Christian universalistic view. It is a universalistic – where kind of everyone has the same capacity and the world mirrors something, some spiritual world. So we’re kind of mirror images of one another. And we’re trying to flip the script to bring our material world into that spiritual world. That’s the world of remez, illusion, which I think is a very Christian approach. And Christians, you should know, spend a lot of time on remez, on allegorical approaches to the Bible. There’s a writer named Frank Talmage who wrote an article about how Christians approach this four-part structure called Pardes, peshat, remez, derash, sod. So peshat is atheistic. Remez, I believe, is Christian.

derash are the brothers and sisters of Judaism and Islam. Judaism and Islam are – both center commandedness and law in our lives because we’re not trying to reverse the material into the spiritual, we’re trying to wed the spiritual and the material together. We’re trying to bring them together and fuse them together in different ways, but the notion of an oral law is very much a part of Islamic tradition and Islam has a jurist and a legal system. It’s very, very robust, whereas Christianity is much more by faith alone, not by, you know, acts or deeds or whatever it’s called in whatever Christian movement they’re in. So the world of derash, in my opinion, is the Jewish approach which is the wedding of the spiritual, not flipping, which is like allegorical, which is like it’s the mirror image.

Then finally the world of sod is Eastern religions. Eastern religions are experiential. They’re before language. So they don’t really give you a vocabulary to build community, society, culture, which is why I think Eastern religion has really struggled in many ways in the West. But its emphasis is purely on the experiential, on what’s happening inside. It doesn’t really have a mechanism for how to integrate sod into your daily life when you’re driving in a car or at the supermarket. It requires a transcendent, almost a removal to get to that place that’s pre-language, that’s purely experiential.

But I do believe that all of these religions contain a capacity, a very real reflection of the divine idea. I think you’ve seen that plainly in Jewish texts as well. Everything is a reflection of the divine, especially a force as powerful as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. I don’t look at the world and just say, anybody who’s not Jewish made a total mistake. These are very real energies and forces that exist in the world and I think that this framework, at least for me, helps understand the different emphases of the different religions.

LEVY: What’s interesting is that the last one you said was sod, which is the secret that you referred to as experiential. And you said that Westerners have had a hard time with that Eastern element of religion. If you look at the places where that Eastern element of religion has had an influence in the West, it’s in places like meditation, it’s in places like yoga, which is almost often for most people a moment in the day where they actually have to leave what they’re usually doing. And they have to go into a specific experiential framework.

But what’s also interesting is that one of the kabbalistic approaches to text is in Sefarad [the Iberian Peninsula], where they reverse the acronym and they put the samech, the last letter first. And then if you’re looking through the Eastern, through the peshat, remez, derash, what you’re actually doing is saying, how do I infuse the spiritual into the physical as opposed to leaving the physical to go to the spiritual? And that’s really what kabbalistic tradition is trying to do. It’s trying to, whether it’s how I eat, how I drink, whether it’s how I interact with people, how I can infuse that in my life.

BASHEVKIN. Well, the great Vilna Gaon, who was one of the greatest kabbalists who ever lived and one of the greatest halachic minds and Jewish leaders in the eighteenth century, he writes that the ultimate expression of peshat is when the peshat, the plain meaning, coheres with the mystical approach and that they’re supposed to cohere with one another.

So I think the ultimate secret, so to speak, is learning how to look at this material world, seemingly absent of God, and look at everything as completely infused with God. It’s when the peshat and the sod, the plain meaning and the secret, are suffused with one another.

LEVY: So does someone need to be religious to study Jewish mysticism?

BASHEVKIN. To study Jewish mysticism? I don’t think so. I mean, what does it even mean to be religious? To study Jewish mysticism, as I said before, reading the words, I mean some of the great academic scholars, Gershom Scholem, for example, spent his entire life [involved in mysticism]. He was not a classically religious person, though I think he had a very deeply religious soul, but he was not a classically religious person and he has a lot of works that I think do some measure of justice, some are better than others, explaining the basic underlying ideas. That’s called studying mysticism. So it’s like learning a new language.

There’s a difference between when you learn a new language so you can know how to translate the words, like with Duolingo; you know how to put some words together. You might even speak totally fluently. But the only way that you’re going to be thinking in that language, where you’re [dreaming in it] and it’s fully a part of you where you can almost think of two minds, which people who are bilingual know what that means to be of literal two minds, where you’re not taking one word and translating to another but you have two worlds that you can enter in your mind. That to me requires a religious outlook. The experiential component of mysticism, which is its ultimate essence, requires a religious orientation.

What is mysticism if there is no God and it’s all not real and it’s all kind of made-up phony baloney?

LEVY: Can Jewish mysticism be dangerous?

BASHEVKIN. I think so, absolutely. I think anytime you are engaging with your own purpose and the ultimate meaning of life and existence, you can end up warping, you can end up convincing yourselves of realities that may not exist. I think anytime you are trying to get to the essential answers of anything, it is dangerous, there is risk involved. Of course there is risk involved.

I would look at it the same way as you would talking something out with a parent. If you ever speak something through with a parent. So there’s risk involved. Why? Because if I talk this out with some random friend and they don’t approve or they don’t like it, okay, I could dismiss it. You talk to your dad, your mom and they disapprove or something comes off wrong, you’re crushed, you’re broken. Why? Because you’re getting to the essence of who you are, of your very – you’re talking to your parents.

So I think mysticism in many ways is trying to get to the essence of Judaism, of God, of divinity in the world. And there is a danger when we deal with the essence, when we try to understand what is at the heart of life itself. It’s very easy to misinterpret and go in wrong directions. It’s also very easy to become almost nihilistic where nothing has any meaning. If everything has meaning, then nothing has meaning and you feel that. You could get stuck and pulled into that world where your own agency, your own perspective, the own reality of your life can become effaced and become just all part of this transcendent, meditative planet that can become nihilistic or antinomian, which means that you stop really following the law and believing that there’s a sense of commandedness and actual purpose.

So I think mysticism can be dangerous, which is why any time that we deal with the essence, any time that we deal with the most essential, we have to approach cautiously, carefully, and thoughtfully.

LEVY: It’s interesting. For those that study Kabbala seriously and mystical texts, there’s a special prayer you say before, there is special preparation you make to be careful with what you’re dealing with.

BASHEVKIN. Anytime that you are dealing with something essential, if you bring in your shmutz, your garbage, your baggage into what’s most essential, it’s going to really mess things up. I mean, the most sanitized place in the world is a surgery. When you open up the body, you have to make sure that there’s no viruses, chemicals, whatever is going around. So they sanitize so carefully. When you open up the heart of the world, of purpose, of divinity, if you bring in your own baggage, your own garbage and you’re not worked out, you’re not developed as a person and you bring in all of your own trauma and brokenness and alienation, you can end up destroying yourself and the entire world.

LEVY: I love that analogy. But the truth is surgery is there to fix something. So you sanitize the surroundings but you go deep and the surgeon gets messy in that process.

BASHEVKIN. Yeah, sure. It’s messy.

LEVY: Because that’s how real healing happens.

BASHEVKIN. Yeah, exactly.

LEVY: Amazing. I’ve asked these questions of many different people and you’re the first person that has answered the definition of Jewish mysticism as something that’s experiential. And I love that. And it means it’s effusive. You and I both are experiential educators. And part of that element is really being in an immersive environment and having it come to what we do. And a lot of what Jewish mysticism is about is personal relationships, is deep, meaningful interactions. I’d like to ask on a very personal level.

Moments ago we had an interaction with your children, with your family, and we live in that environment as we step out. Has Jewish mysticism and this learning of this tradition impacted your own personal relationships? And do you have any examples of that lens and maybe how that has happened?

BASHEVKIN. Undoubtedly, having a family, being married and committed to my incredible wife Tova and the children that we have is the center of my mystical Jewish life. I believe it’s the Vilna Gaon, once again, who writes that the ultimate litmus test for one’s piety, for one’s holiness, for one’s progress spiritually is their relationship with their spouse. I think, and I actually caution my students to stay away from educators, rabbis, and people who don’t have healthy familial relationships. I think really learning how to find nourishment and meaning from your spouse and your children is at the heart of Judaism. It is the holiest place.

I often times say the Holy of Holies, the Kodesh HaKodashim, the inner sanctum of my life is not the beit midrash [study hall], it is not the synagogue, the shul. It is my home. It’s the Holy of Holies. And I would say, I’m trying to think of something specific.

The recentering of my life and the centering of my family as my number one religious priority. And that’s different than my number one priority. It’s my number one religious priority. How I look at myself, am I a big tzaddik [righteous person], am I not a big tzaddik, is not something I explore when I’m davening or it’s not something that I explore when I am learning. It is a question that is in the hands of my wife and my children. They are the ones who decide what is the impact that I will have on their lives. And I have centered that very deliberately because I think the ultimate redemptive expression of mysticism is finding that pleasure, that joy in giving to your immediate family. I think the ultimate expression of the mystical idea of the connection of the reunion of husband and wife is that ultimate rectification of the original sin.

There is a phenomenal idea that I was first introduced to actually by Rabbi Judah Mischel. I remember where I was sitting when he told it to me. It’s from the Beit Yaakov, who was actually a son of the Rabbi of Izhbitz and a contemporary of Rabbi Tzadok, Rabbi Yaakov Leiner. And Rabbi Yaakov Leiner writes in Beit Yaakov that speaking about the sin of Adam, Adam’s wife, Eve, first ate from the Tree of Knowledge. And then she gave it to Adam to eat. And the question that many people ask is: Why did he eat? He knew better. He knew he wasn’t supposed to. He knew it was prohibited. So why on earth would he do that?

The Beit Yaakov says something that is absolutely astounding and has moved me ever since. He says that Adam knew that he was not supposed to, and he also knew that he would be banished from the Garden of Eden. But the problem is, he knew that his wife already ate from the tree.

So he knew that she was going to get banished already. And he said, if I’m going to be here without my wife, then it’s not really paradise. So he ate deliberately from the Tree of Knowledge to exile himself to be with Eve.

I believe genuinely that the purpose of the world is you finding that zivug, finding that companion, finding that other and learning how to sanctify your commitment. It’s called marriage. Some people merit to have many children, some people are never married. Rabbi Tzadok never had children and it pained him deeply. But at the very heart of existence is being willing and having the courage to say that if it’s without my spouse, if it’s without my family, then it’s not paradise.

What we’re doing is we’re going into exile to ultimately rebuild that paradise, but it’s the paradise that we build with our spouse together. Because without my spouse, like the Beis Yaakov interprets in that story of the first sin of Adam, if my wife’s not here, it can’t be the Garden of Eden. It can’t be paradise.

LEVY: Beautiful. Chadeish yameinu kekedem, to come back to that time. That Torah that we said. And also, that’s the idea in the Sheva Berachot [seven blessings for a wedding], we actually say to go back to that time because it can only be achieved through the union of the relationship with the other.

You’ve shared so many beautiful ideas as they relate to practical questions that I’ve asked. I’d like to ask as we conclude just for an idea. What is a beautiful Jewish mystical teaching that you take with you wherever you go or that’s resonating with you at this moment that we can share with those that are listening?

BASHEVKIN. Rabbi Tzadok writes in the forty-first paragraph of Tzidkat HaTzaddik. He has a very short but profound idea and one that I think about a lot. We have a concept that you may have heard if you had a traumatic elementary school rabbi like myself. I don’t remember which one said it to me. But a lot of people, maybe it was a camp rabbi. They said that every time you do a mitzva, you create an angel. And if you do a mitzva, this is what the rabbi said that traumatized me. If you do the mitzva incorrectly then the angel is born without an arm or without a leg, and it’s disabled and all this stuff and I’m just like, okay, that’s really stressing me out. That’s not helping. But it’s based on a real midrash [expansive biblical exegesis] that you get an angel for doing a mitzva.

And Rabbi Tzadok says something absolutely astounding. He says, the reason why you get an angel, so to speak, for performing a mitzva is because the angels are the shaliach, are the messengers of God, and we accepted the mitzvot through a messenger. Moshe was God’s messenger and taught us the Torah. So the reward for keeping the Torah is we get our own messenger to protect us. And that’s the concept of that angel that you create, that divine assistance that you get.