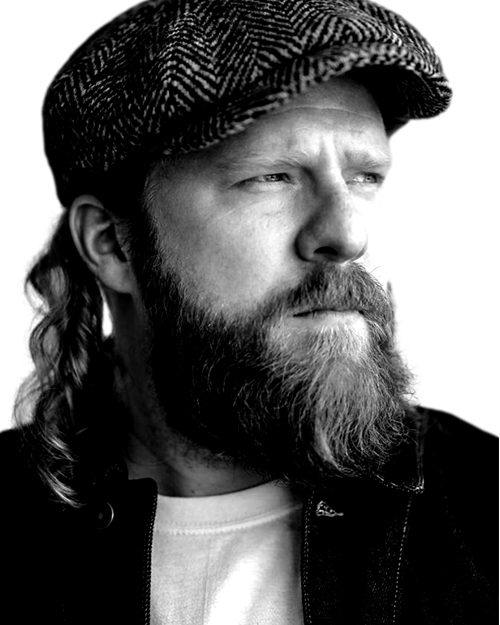

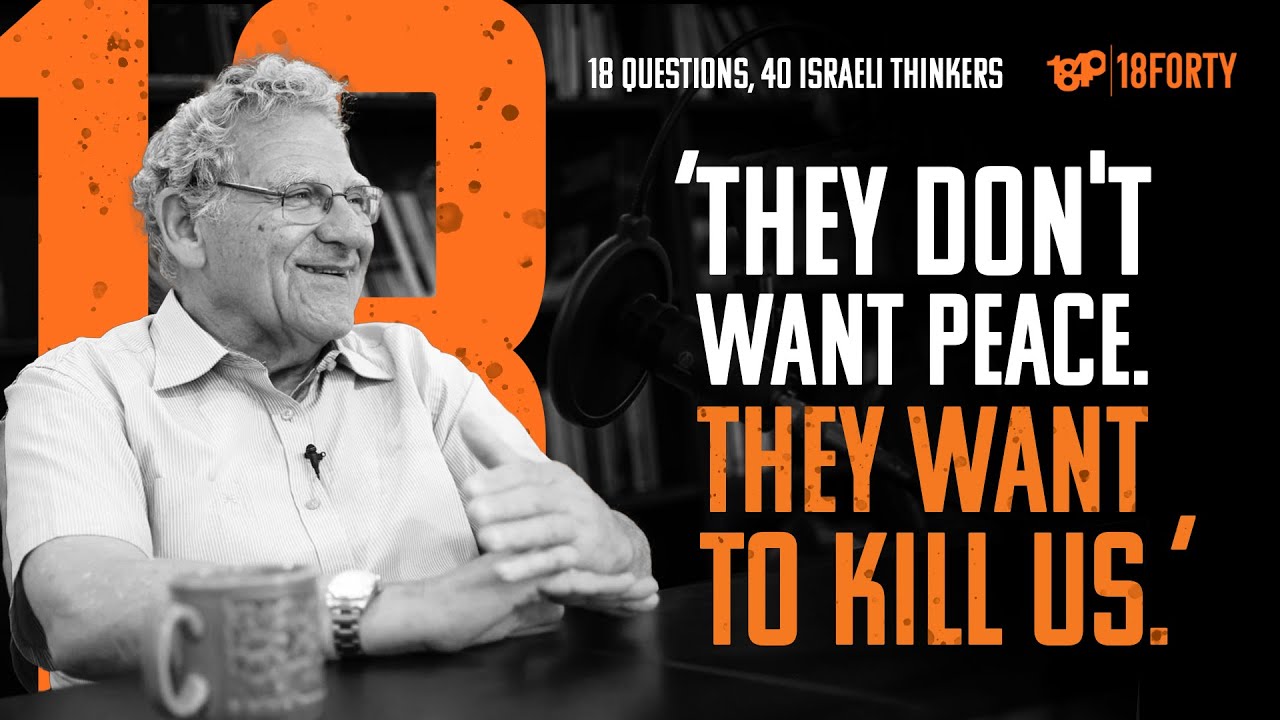

Mark Wildes: Is Modern Orthodox Outreach the Way Forward?

We speak with Mark Wildes, founder and director of Manhattan Jewish Experience, about Modern Orthodox outreach.

Summary

In this episode of the 18Forty Podcast, we speak with Mark Wildes, founder and director of Manhattan Jewish Experience, about Modern Orthodox outreach.

In this episode we discuss:

- Why aren’t more aspiring rabbis attracted to kiruv?

- How can we help people make the transition from outreach programs to the “real world”?

- How can we make the case for Shabbos for the masses?

Interview begins at 22:45.

Rabbi Mark Wildes was ordained from Yeshiva University, but before becoming a rabbi, he received a JD from the Cardozo School of Law and a Masters in International Affairs from Columbia University. Since founding MJE 20 years ago, Rabbi Wildes has become one of America’s most inspirational and dynamic Jewish educators. He lives with his wife Jill and their children Yosef, Ezra, Judah and Avigayil on the Upper West Side where they maintain a warm and welcoming home for all.For more 18Forty:

NEWSLETTER: 18forty.org/join

CALL: (212) 582-1840

EMAIL: info@18forty.org

WEBSITE: 18forty.org

IG: @18forty

X: @18_forty

WhatsApp: join here

Transcripts are produced by Sofer.ai and lightly edited—please excuse any imperfections.

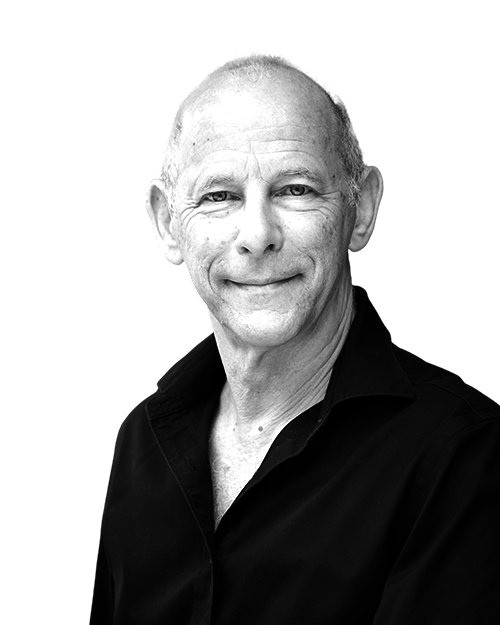

David Bashevkin: Hi friends and welcome to the 18Forty Podcast where each month we explore a different topic balancing modern sensibilities with traditional sensitivities to give you new approaches to timeless Jewish ideas. I’m your host David Bashevkin and today we are exploring the topic of Modern Orthodoxy and kiruv, Jewish outreach. This podcast is part of a larger exploration of those big juicy Jewish ideas so be sure to check out 18Forty.org, that’s 1-8-F-O-R-T-Y.org where you can also find videos, articles, recommended readings, and weekly emails. The question of modern orthodoxy and kiruv is a difficult question because it really is a question that begins with terminology.

What exactly do we mean by modern orthodox and what exactly do we mean by kiruv? And over here I’ll just speak kind of colloquially, the modern orthodox world communally is a very porous community. It does not have very firm boundaries of what you would consider Modern Orthodox versus not modern orthodox. So the first part of our question we are left with a lot of ambiguities of how should we define Modern Orthodox. I’ll be honest, just when I say that question I get tired, I get exhausted.

I do not enjoy conversations about kind of defining communal boundaries. I think all communal boundaries are somewhat porous, one kind of bleeds into the next and it’s very hard to find where’s the exact slice, where’s the exact line that you go from yeshiva community to Modern Orthodox community, yeshiva person to modern, like I just don’t think in those terms. I think there are kind of maybe examples that are easier to categorize and you could stay with those, but I don’t like really spending time in those differences, though I think colloquially we understand that different communities have different cultures. The second part of the question I think is also tricky which is what exactly is considered Jewish outreach? There is a professional world known as professional Jewish outreach where people as a part of their career spend time bringing Judaism to others.

In some communities this is called adult education which is such an unattractive term to me. Adult education, I don’t know why. I just like education, I don’t know why we had to add the word adult. We mean something I think more than that and we also mean something more than let’s say a Jewish communal professional, somebody who works in a Hillel or in a federation.

The differences are more complicated than you would think because somebody who works for a Hillel has a point of view, has an agenda even if that agenda is kind of a more pluralistic vision that Hillel adopts, but you kind of go out and you kind of share your version of Judaism. At the end of the day the only thing that we teach is ourselves. The only thing that we can teach is ourselves. Even when we’re teaching a text or daf yomi, we are teaching ourselves, our own understanding of everything and the only thing that we do is we teach ourselves.

Like what is the Yiddishkeit that I hold and I try to share it with others and share that perspective with others and hopefully it will contribute to your formation of self and the way that you think about the world and the way that you think of Yiddishkeit. But kiruv is something specific also. It does not include anybody who works for a federation, it does not include anyone who works at a Hillel. I think there’s something very specific that we mean from kiruv and that is programming that is meant to introduce people to the foundations of Judaism in the hope that they will build their lives in a way that the kiruv professionals consider Jewishly sustainable.

And I would say I kind of agree with them 99 out of 100 times. I think that for all of the difficulties that the kiruv world has kind of gone through demographically, it’s much harder these days, you can meet somebody with no Jewish background, with no Jewish education, so if the nature of kiruv is introducing them to their own Judaism and to Jewish texts with the hope that they continue it for the rest of their lives, sign me up. I have no problem with that whatsoever. Everyone should be in a mindset of continuous growth.

There are also other aspects to kiruv that have gotten some attention that people don’t love, which may be kind of being a little pushy, making sure that you know we want you to sign up for yeshiva for the year or go there and when you have a specific outcome in mind, which I think in the holiest of ways the outcome that the kiruv movement is looking for is sustained Jewish life, a Jewish life that is sustainable that’s going to continue on not just for the point and the period in your life where you are right now, but everything that comes after it and all the future generations that come after it. I think it’s very noble and in some ways it can get a bad rap, some of which I am guilty for. I bristle sometimes at the… one of maybe the ease, sometimes it’s oversimplified of just like here, it’s so obvious, of course, become totally frum and this is the way to do it and we’re going to prove it to you and we’re going to show you that this is undeniable, there’s no other way to live.

I appreciate the enthusiasm, I sometimes bristle because I’ve seen it with my own eyes backfire. We’ve had multiple people who the beginning of their almost distance from Yiddishkeit, from Judaism, from Jewish life, began with an overzealous educator, somebody who pushed maybe a little bit too hard. And that’s an experience that everyone has had. Everyone, I mean, whether you have participated in Kiruv or went to Yeshiva or everyone has had experiences with teachers, with educators, with Rabbeim, with a Mora, with a Rebbe in Israel, with a rabbi in a synagogue, whatever it is, who didn’t align to our own capacity, pushed too hard, didn’t push hard enough.

And so much of the blessing in life is finding the ideas and the visions that really work for us internally. At the end of the day, the only thing a teacher can teach is themselves, what they understand, what they know, what they’ve experienced. So where does that kind of leave the definition of what constitutes kiruv? What constitutes kind of the world of Jewish outreach that we are talking about? I think it means that there is somebody formal who is getting paid, like this is their job, the same way that the rabbi of a shul has a job, same way a marketing director at a federation has a job, the same way a professional at a Hillel has a job. There is a job called Kiruv, called Jewish outreach, where the goal of the job is to introduce the foundations of Jewish life to as many people as possible.

Now here is where kind of the conundrum and the focus of today’s conversation comes up, and that is, I think broadly speaking, and it’s hard to put an exact date on it, but much, if not all, but much, a very large majority of the professional outreach world is not populated by people who would describe themselves or at least align with the Modern Orthodox community. Most, not all, I’m painting in fairly broad strokes, most people who dedicate the entirety of their lives to Jewish outreach come from a more classical Yeshiva background. Now I am kind of of the opinion that there’s nothing wrong with that. We’re introducing Judaism, getting into these minutia and details—yes black hat, no black hat, what do you say on Yom Ha’atzmaut, do you say Hallel, no Hallel—these things is like we are dealing with such niche minutia that it’s totally unnecessary when you have the majority of American Judaism know absolutely nothing about Jewish life and Jewish text.

We are dealing in this kind of like pivotal endgame moment where we’re trying to figure out, like, who’s with us? Who’s going to be a part of this project called Yiddishkeit, called Judaism? And unfortunately, for so many, the actual life, what Jewish life entails, they’re removed from it. They were never really told, they were never educated. They don’t know about a Yom Kippur, they don’t know about a Rosh Hashanah, they don’t know about what consistent Shabbos observance can look like and how it can transform your home. And this is why I actually think when it comes to outreach, although like I don’t really pay that much attention or I don’t really think it makes that much of a difference whether or not someone is from Chabad or a Modern Orthodox community or from a Yeshiva community, we have all been given the gift, the common denominator is we’ve all been given the gift of a very rich Jewish education.

If we grew up in any of these communities, it places you very likely in the top one percent of kind of familiarity with Jewish life among the American Jewish community, that I don’t know that those differences are so important except for one factor. And that factor, in my mind, is what happens afterwards. Where do they go after? What happens after the last semester on a college campus where you go to Hillel, where you have a Shabbos, where you went to classes? Where do you go afterwards? Where is the community that you seek to build your life? Where do you hope to raise your children? What do you hope that that looks like? And this, I believe, is where it gets much trickier and kind of the emphasis on communal representation actually does have unintended consequences that I may or may not be reading correctly, but they certainly exist, which is, are we presenting a model of sustained communal affiliation? Do we even have a model of sustained communal affiliation where people who were not raised within an Orthodox community and then choose in their long term to live within an Orthodox community, what should that Orthodox community look like? Where is the right place for them? This is a question that everyone grapples with. Where should I live? Where should I raise my kids? I think it becomes much more acute when you are kind of of two souls—someone who was not raised within the Orthodox community, so they have all of their that is where they’re going to have the most sustained long-term Jewish connection.

And I say that myself with a great measure of pride. I don’t think that everyone is capable of living in an Orthodox community. I don’t think everyone is capable of becoming Orthodox. I hope to be proven wrong.

Who knows? But I do marvel, absolutely marvel at the depth and the richness and the level of education, the level of passion with all of its problems. There’s nobody who is more acutely aware of the problems within the Orthodox community, probably a handful of people, but yeah, I’m acutely aware. But with all that being said, I still marvel at the current global landscape. What is a community that is engaging with modernity and helping people build lives and providing them with a sense of community? I think that the current Orthodox community, particularly in the United States, is nothing short of a miracle.

It is jaw-dropping. It is my own story. I am a product of somebody who decided to really build his life in the Orthodox world when he was a teenager. That is my father.

But one thing that I think makes my father’s story kind of interesting and it was from a very specific slice of time is that the anchor, the lever of my father’s kind of own religious transformation was spearheaded by what we would I think all agree is the Modern Orthodox community, that is Yeshiva University and NCSY, which was back then known as the National Council of Synagogue Youth. Now full disclosure, I worked for NCSY for over a decade and have extraordinarily fond, reverent feelings for NCSY. And NCSY, I think, does serve as an incredible example of what I would call Modern Orthodox Kiruv. Does a really fantastic job of Modern Orthodox outreach introducing the Modern Orthodox community.

The only difference and why I didn’t kind of begin with that is because it targets exclusively high school kids. And high school kids do not have the same autonomy. There is no NCSY on college campuses to my knowledge. And NCSY is also mostly populated by non-professionals.

I think this is part of the magic of NCSY. Literally, most of its staff is volunteer college-age advisors, which I think is part of the beauty. It introduces a very organic Orthodoxy. You’re not hearing the principles from a rabbi or from a scholar.

It’s very organic. You’re hearing it from a twenty-year-old who himself is working through issues or herself is working through issues. I think that is part of its attraction and sticking point. Part of what I think NCSY does a fantastic job, I think there are three factors.

One is most of the staff is non-professional. Number two is that Yeshiva high school students, students who are in a Yeshiva high school and students who are not in a Yeshiva high school or just in the more standard public school have opportunities to interact in a very sweet but also careful way. They’re obviously going to influence each other, but it comes out in a very wholesome, very sweet way that you see in NCSY, that we don’t kind of cordon off the Yeshiva day school kids in one room and the public school kids in another room, but there are opportunities for real interaction. You get a Yiddishkeit that is much more I think authentic when it is organic, when it’s lived, it’s not pre-packaged, it’s not proven.

It is just the way of life where the actual motivation is instead of theological principles, what motivates it is the experience itself. S’char mitzvah mitzvah, the reward for a mitzvah is the mitzvah itself. The reward for Shabbos is Shabbos itself. The reward for keeping Halacha and Jewish law is a life that is tethered to something, that is tethered to transcendence even in my most mundane moments.

The final factor that I think makes NCSY so successful, and when I talk about its success, I’m not even talking about the numbers of people who decide to live in the Orthodox world. I’m actually not sure that those are such amazing numbers. I think that its success is the fact that those who go through the system of NCSY are really able to integrate quite seamlessly into the lived Orthodox community, which I think is a very good, though not, nothing’s in there, no guarantees in this world, is a very good predictor of kind of like a really sustained long-term Jewish involvement. And I think that’s absolutely wonderful.

A lot of that is a product of, again, the age, high school age. It is right in between the teenage years, which I think have always had a real space in Jewish law because it’s between Bar Mitzvah and when you turn twenty. You become responsible at the age of Bar Mitzvah, Bar Bat Mitzvah, twelve or thirteen, and you become capable of actual punishment in court at the age of twenty. The language, and I think I heard this once from Steve Berg, who is now the national director of Aish, but the language I would use is that the teenage years are in between responsibility and accountability, and there’s something very special that happens during those years.

So NCSY has done a fantastic fantastic job of that, and there are programs at Yeshiva University still run, my father used to participate in Torah Leadership Seminar and now there are other things, maybe Torah tours, but by and large, and here’s kind of the bottom-line truth, as a professional aspiration and as a professional career, there are very few people from the Modern Orthodox world who then dedicate their professional lives to Jewish outreach. If you walk into Yeshiva University’s Rabbinics program and you ask what do you plan on doing, where do you plan on practicing as a rabbi, you’ll hear a whole lot of pulpit rabbis and too many of them just want to be in the tri-state area. We need more pulpit rabbis. You’ll hear a whole lot of educators, which is wonderful, we need more educators.

You will not hear that many people, sometimes you will hear none, maybe a handful, maybe less than a handful of people who I want to go out, I want to go onto a college campus, I want to bring Judaism to those who are unaffiliated. Now, this can be a product of a whole lot of things. I’m not even sure how much it helps to speculate. It’s a product in many ways of the financial demands of a Modern Orthodox life and the amount of money that you can potentially earn as an outreach professional, which is not that much.

It’s not as much necessarily as you can get in other fields, and you grow up in a Modern Orthodox community, get used to a certain socioeconomic status, and you kind of cross off jobs. But that doesn’t fully explain it because it doesn’t really explain why no to kiruv, but yes to being a seventh-grade rebbe, which not to say that people are pouring into be elementary school rebbes as they should, but you still get people who want to dedicate their lives to that. I think the biggest factor is kind of the stability of community, where if you teach in a school, in a Modern Orthodox school, so you may have to switch schools every couple years, especially if you’re a principal or a head of school, but there is a certain stability in that institution. And there’s a certain stability that you can kind of have growing up being a pulpit rabbi of one community.

I think it gets a little bit harder, and maybe I’m just projecting my own concerns of finding that lifelong outreach. A lot of the image of what outreach looks like from a distance is like the wildest, most geshmak person in the room, the person who’s jumping on the tables and making everybody excited. And I understand why some people wonder like, is that sustainable, is that something that I can continue doing throughout my life? What am I going to look like when I’m in my forties and fifties and sixties? Not to say that there’s not a model for this. I think the model that hovers over everything is Chabad, which is very deliberate in not calling itself kiruv, because as the Rebbe one time said, which is a very sweet beautiful line that I think applies to everybody but it’s specific in Chabad, is he doesn’t call it kiruv, which means to draw somebody close, because how do I know that you’re so far and who says that I’m so close? Instead they use the term being a mashpia, which I think is a very beautiful term, which comes from the word shefa, which means to overflow.

We fill ourselves up and then we keep on flowing to our children, to our family, to those around us, and there is something a little bit organic about that. But the lament that I have and why I think this is such an important topic is that people like my father and of my father’s generation and I think people who live now maybe not within the tri-state area and they’re looking for a model of community that is sustainable, that is welcoming, that is culturally they’ll be able to navigate it, I really do believe that the Modern Orthodox community offers a tremendous amount to the wider American Jewish community. I don’t think it’s been fully realized or fully unlocked. And I know in my community there are so many people who did not grow up in a typically religious community and even though our community where I live in Teaneck is not, it’s certainly not Lakewood, but they really find a place for sustained Jewish life, for that communal metronome that kind of just like stays on beat day in and day out and you’re living adjacent to this community of practitioners.

And I wonder, why is it that the Modern Orthodox world has struggled so much with kind of articulating or even having a strategy for outreach outside let’s say of NCSY? Where does that come from? Again, some of it I think is socioeconomic. I think some of it is also theological. I think a lot of people are uncomfortable giving religious guidance, advice to others. When you feel insecure, inauthentic in your own life and you kind of have this attitude of just live and let live, let everybody kind of do their own thing, then questions of a proactive message of each person has a way to maximize their religious life, people can be uncomfortable with that.

And I understand that, I get that, I think it’s something that we need to develop more confidence in. It’s something that Rav Lichtenstein once said: insecurity is the Achilles’ heel of Modern Orthodoxy. When we don’t feel like we are authentic, and I’m using we because I consider myself Modern Orthodox in many ways, so I try to bring in the flavors from all the communities and the yeshivas that I’ve studied in, I live my life and send my kids to a school that I think would be fairly described as Modern Orthodox and I look at it as such an incredible return on my investment, my communal affiliation is one of the most wonderful decisions I’ve ever made in my life, I am not shy about the fact that I think more people should be kind of figuring out what their relationship is to community. I think we live at a moment where we have seen the utter breakdown of community.

We have communities that are too authoritarian, too suffocating, they’re not really going to be a sustainable model for most people who are looking for a religious communal destination in their lives, I’m not judging, I think some people want a very insular tight-knit community, we need more of them, but it’s not going to work for everybody, I think that’s a fair enough thing to say. And yet we have throughout America a crisis of a deterioration of community. So what is the model of community that the Jewish world can hold up and say, if you are looking for Jewish communal life, if you are looking for kind of that sustained connection, where should you turn, where should you go? I grew up in the tri-state area, I live in the tri-state area, this is where I feel the most that I don’t think this is for everybody and I get that, I understand that. So where is it and how do we get it and how do we create more neon entry signs that more people can find it and discover it? In many ways, that is the topic of today’s conversation where we both diagnose the problem and try to explore ways to address it and I’m speaking today with an incredible Jewish professional, Rabbi Mark Wildes, Rabbi Mark Wildes, who has really alumni throughout the entire world from his incredible program MJE, the Manhattan Jewish Experience, a staple of our community and somebody doing absolutely incredible work within the Modern Orthodox community and trying to articulate a vision outwards to those who did not grow up within the Modern Orthodox community, did not grow up with much Jewish community at all, I wouldn’t say zero Jewish community, but certainly outside of the Orthodox world and articulate a vision for Modern Orthodoxy that can be that neon entrance sign that can show people that sustained communal affiliation in the Jewish world is still possible.

While everybody else is bowling alone, there are pockets of the Jewish world where our greatest strength is our community and if only we could introduce this to more Jews, I think we would all have a more sustainable Jewish life. And when I say this, I mean Jewish community. What can and should a sustainable Jewish community look like? Why is it that the Modern Orthodox community has struggled in many ways when it comes to professional Jewish outreach? All of this in my conversation with Rabbi Mark Wildes. So really thank you, this is an incredible privilege and to be with MJE alumni at this moment is really, really moving because I think when you look around at the landscape of the American Jewish community searching right now post-October 7th for a model of Yiddishkeit, it is incredibly comforting to know that there are people who are really doing the work in creating a model, creating doorways of entry for people to come in.

We talk very often on 18forty about how rooms generally have neon exit signs and what we need in the Jewish community are neon entrance signs and that you have been spending the last 27 years putting up neon entrance signs that people can walk in and build Jewish families is really incredible. But I wanted to start with a bit of a hardball question when it comes to talking about kiruv and outreach. Kiruv is a Hebrew term that we talk about to draw somebody close and we talk about how we want to bring spirituality into people’s lives. But there is an element of the modern kiruv movement, the outreach movement, that is tethered to a specific denomination, namely the Orthodox Jewish community.

The common denominator of the alumni of what you’re trying to cultivate is someone who attaches themselves, connects and starts building roots within the Orthodox community. I want to open by asking how you think about Orthodoxy specifically in the prism of outreach. Do you think when somebody walks in the door of MJE or do you think every American Jew in this moment has the potential to live a fully integrated Orthodox life?

Mark Wildes: Okay, that’s an excellent question.

David Bashevkin: Let me develop why I think that’s such an important question at this moment.

There is an awakening that is happening right now post-October 7th. We are talking about it in the pages of Commentary, Dan Senor said it quite famously saying we need to invest in Jewish education, we need to invest in Jewish engagement and I’m sure most people who are a part of the Orthodox community are listening to these calls and are saying, hmm, we actually might have an answer here. Yeshiva University put out a public call saying, if you faced antisemitism on campus, come on over to Yeshiva University, we’ll be your new home. And a part of me in the Little back of my head says I don’t know if your average American Jew would be able to function in YU.

It’s designed for a very specific socio-cultural unit called the contemporary tristate area Modern Orthodox world. Zeh lo Yiddishkeit. Zeh lo, you know what I’m saying? That’s a difference between that and Judaism. Yet we need a vision for Judaism.

So my question is the role that Orthodoxy plays when you’re in outreach, do you come in and assume that everyone’s best option is to join the orthodox community?

Mark Wildes: It’s an excellent question. I make a big chiluk, a big distinction between turning people on to Judaism and orthodoxy. I can’t use that word. And I probably when you came to MJE didn’t use that word because it’s a scary term for most American Jews that are not Orthodox.

I talk about spirituality, I talk about commitment and enlightenment and spiritual wisdom and I’m part of the Orthodox community and a proud card carrying member of the Modern Orthodox community but unfortunately it’s a bit tainted that word. So I don’t use that term. I talk just about Torah. To answer your question, I think there’s a place for every Jew somewhere in Judaism.

Is there a place for every Jew in the Orthodox community? I’m not so sure. I’m not so sure. I meet people all the time that I feel can date exclusively Jews and maybe come to some classes and maybe they’ll show up on Shabbat at 11 o’clock and hit the kiddush afterwards but I’m not sure that they’re necessarily going to become a Torah observant Jew. But there’s a place for that Jew in our community too.

Orthodox synagogues used to be places for Jews whether they were observant or not and I think we need to bring that back. I’ve been trying to do that for a long time. The beginners service that many of you guys came to for a long time we just had this morning, it’s designed for people to come and daven. We don’t ask people how observant or not observant they are or what they’re doing with this or not.

We just want them to come and pray and be part of the community. But I do think that everybody has a neshamah and that neshamah needs to get connected somehow to Torah. Whether they’re going to take it the full way and become a part and parcel of the orthodox community is a very, very personal choice and a lot of factors but it’s not going to work for everyone. But I do think we should be trying to get as many people, more people and I don’t think the modern orthodox community specifically is doing its share.

David Bashevkin: I love that you mentioned the notion of the Orthodox community, synagogues, shuls that used to have many that were not Shomer Shabbos. I am a product of such a family. My Zaidy, he was not Shomer Shabbos until he conveniently retired from work, it’s a great time to start. But he was not Shomer Shabbos his entire career and my father really was in name in an Orthodox home but only really became fully committed in his teenage years through NCSY.

My father’s NCSY counselor, the person who really made him frum was somebody who I’m sure everyone has heard of who back then was known as Stevie Riskin. Rabbi Riskin was my father’s counselor and he drew in many to frumkeit. And that really does make sense to me and that work, NCSY, which I was affiliated with for many, many years, continues to do that work and it is situated within the Modern Orthodox community. And yet, I do sometimes sense there is a reticence of sorts within the Modern Orthodox community to engage in Jewish outreach.

It is not a long list when I look at the landscape of people who go into Jewish outreach. I wouldn’t call you an anomaly like you’re the only one, but there aren’t a whole lot of you, people who into adulthood set up a synagogue and they’re specifically trying to reach the unaffiliated. Do you think Modern Orthodoxy has an issue with outreach? If so, why do you think so?

Mark Wildes: So before I answer I do want to say because what I’m about to say might sound a little negative about my own community. I drank the Kool-Aid when I went to YU.

I’m a YU guy. I believe in Torah u-Madda, I believe in Religious Zionism, I believe in more women integration and leadership roles and when people ask me Mah nishtanah MJE from other outreach programs I say we are Modern Orthodox in our hashkafa, in our outlook. But we’re not passionate about kiruv. We’re not.

There are a couple of reasons possibly. I always like to say kiruv is, you know, if you go to a good movie and you really like the movie and you come home and you see your wife and you really like your wife you’re going to probably tell her a little about the movie or if it’s a book and you’re going to want to like connect the person you love with the thing that you just really appreciated. If you love football, you talk about football. Whatever it is, yeah.

So if we as practicing Jews are not sharing the love and passion we have for Yiddishkeit with those who were deprived of it in their youth, then either we don’t care about the people out there enough or we’re not so in love with our Yiddishkeit. And there is a lack of a passion in our community and if we were a little more meshugana about our own frumkeit I think we’d probably be a little more upset that not enough of our fellow Jewish brothers and sisters are practicing it.

David Bashevkin: But I want to push back on that a little bit because I actually think that it is the lack of passion, it is the normalcy kind of within the Modern Orthodox community that actually makes it a perfect entry point. I would have expected that the model of community that would have been best suited to absorb people who are newly frum, did not go through the Yeshiva League, don’t know that floor hockey’s the most important sport in our community—like they don’t know any of this—the easiest way to integrate should be the Modern Orthodox community.

It would be much harder to learn all of the cultural nuances of a Lakewood, of a Passaic. So the lack of passion, almost the level of observance being a drop more accessible, why isn’t that the ultimate—like, it’s so easy to transition, it’s not so hard?

Mark Wildes: Because you need—I’m looking at my wife when I answer this question—who—I’m sorry, I’m looking at everybody here—you need passion. If you don’t see passion, why should somebody give up the lifestyle they’re having in favor of a different lifestyle that requires commitment, discipline, additional tuition money, a lot of additional tuition money? Why would you do all those things for something that’s like a little parve? Okay, it’s an easier transition because you’re not making as dramatic of a change in your life, but to make a dramatic change you’ve got to really see something exciting and inspirational. And that’s why I’ve been advocating Modern Orthodox kiruv my whole career because I think we model certain, you know, ideologies that I mentioned before that I think are so attractive to less-affiliated Jews.

But if we don’t have that passion, if we don’t look like we’re on fire about our Judaism, then what exactly is attractive about it? Because we’re a little more similar, we don’t look as different, we have less facial hair, you know, than some of our Chassidic counterparts, so that’s good, we’re a little less scary. We’re definitely less scary. But what are you getting? What’s the experiential yield? What’s the experiential yield? Exactly. Now I think we have it, because when I spend time with my students and they come on Shabbat—and everybody here I’m sure can attest to this—if you didn’t grow up with Shabbas, and people walking to shul and going to people’s homes and kids running in and out of each other’s backyards, and God forbid something goes wrong there’s a shiva, my students think 125 people is a lot of people at a wedding.

What’s a lot of people at an Orthodox wedding? I don’t want to say the number publicly. Okay, because because we have this and we take it for granted. We don’t realize how awesome it is. And we need to be packaging it and we need to be presenting it and we need to be more excited about it, not to wear it on our sleeve.

David Bashevkin: So I want to come back to Shabbos, but I also want to come back to the example that I said, which was my father’s NCSY advisor was Rabbi Riskin. And Rabbi Riskin was deeply entrenched in Yeshiva University and the Modern Orthodox community.

Mark Wildes: Rabbi Riskin’s success was his passion.

He should live and be well and should continue to do this till 120. Amen. I was in his high school. He started MJE’s New Friday Nights, which is about 9 or 10 years old.

He turned on so many Jews and he turned on the West Side to kiruv. Shlomo Carlebach, Shlomo Riskin, I think get the credit for kiruv in the Upper West Side because he’s got a certain passion. Now, he’s got the Modern Orthodox hashkafa.

David Bashevkin: But my question is why haven’twe produced more? Meaning, we both went to Yeshiva University. Yeshiva University used to run Torah Leadership Seminar.

Yeshiva University used to send out—that there was a point of pride of going to small communities. My grandfather, who was not a product of Yeshiva University, but felt very connected—he was a graduate, the first graduating class of Yeshivas Chofetz Chaim—he was a rabbi in Portland, Maine. That’s where my mother grew up. There used to be a sense of pride of putting up an outpost and building community outside of the Tri-state area.

And now, when more and more when you look at graduates of Yeshiva University who are products of homes in these communities, the kids do not want to go into outreach, they don’t see it as a long-term career. Do you think that there needs to be rebranding about the very profession? Because it’s a calling, it’s a mission. But what is it about the mission of Jewish outreach that has failed to galvanize our best and most promising? Why isn’t that the go-to of every RIETS musmach? It used to be. Where did Rabbi Lamm get his start? He was in Kodima in Springfield where my great-grandparents lived.

Not everybody wanted, you know, the block over in Woodmere and now I’m going to get the next block over in Woodmere. They wanted to go out and build Torah and build Yiddishkeit outwards. Why do you think that sense of passion and building seems to have dissipated?

Mark Wildes: We never had a Rebbe. We had a Rav.

The Rav was unbelievable and the Rav was the intellectual giant of the 20th century and he’s our Rav. But the Rebbe inspired. You know, he’s been gone—he’s gone. Thank you for the confirmation.

For a long time, but look, it just keeps growing. The guys who do the filming and when they all get together, they can’t get them in the same frame anymore. That was never a passion, never exciting. I spoke with Rabbi Lamm, zichrono livracha, he was my teacher, he was a gadol she-be-gedolim, Rabbi Lamm, but that was not his passion.

Kiruv was not his passion. I spoke with Rabbi Halap, zichrono livracha, many years ago who was the head of the RIETS Semikhah program. The Wolfsons came to YU, offered real money for outreach. They’re an academic institution.

They’re not a Kiruv organization. I don’t think we were ever inspired to do that. I think what happened in your-

David Bashevkin: But pause right there. Why is it that Kiruv is considered less academic than being a pulpit rabbi?

Mark Wildes: Oh, I don’t think it is.

I just think it’s perceived that way.

David Bashevkin: Why? Because you can make it up as you go?

Mark Wildes: It’s not seen as sophisticated, it’s not seen as intellectually challenging. When you’re teaching somebody the Aleph Bet or basic Jewish concept, it hasn’t been presented in a way that a student in Rav Rosenzweig or Rav Schachter’s Shiur is going to be like “Ooh, I want to go into Kiruv.” Right? How many Rebbeim are proud coming out of YU want to be a second, third grade Rebbe? In the Yeshivishe Velt, that’s a Kavod.

David Bashevkin: iUsed to be, kind of, sure.

Still a little bit. Still a little bit. There is a pride in that and being a first grade and second grade Rebbe.

Mark Wildes: I didn’t mean to make the analogy between being a second, third grade Rebbe and teaching a 25, 30 year old young professional, but we never put that out as being a- I was assistant rabbi at KJ before I started on the East Side and I have a lot of Hakarat HaTov to Rabbi Lookstein sh’yichyeh and be well and to the whole community there.

I would never have started MJE if it wasn’t for KJ and the Modern Orthodox world, but when people ask me, “What are you going to be doing?” and I told them I’m starting this Kiruv organization, they’re like, “Oh, I guess you didn’t get any real rabbinic offers.” You know what I mean? That was the kind of reaction I got. And there’s a certain kind of respect, a little, from a distance, but it’s not like you’re a Chashuva Rav teaching Torah on a high level.

And I will tell you though, and present company included, you get to teach on a very high level because your students, they may not be well Jewishly educated, but they’re smart.

David Bashevkin: I think teaching on the highest level, I tell people to make the case for Yiddishkeit based on first principles, to be able to take the entirety of Yiddishkeit and literally take from first principles to get somebody eventually to come and dedicate their lives within a community, that requires genius, that requires creativity, that requires brilliance.

But one thing that I wanted to ask about is that process of integration, of really what you are doing when somebody comes in off the street or they come and they find out, they bring in a friend, and slowly they’re going to classes, then they eventually come in. I want to ask about a very specific situation, which may even be painful or difficult to talk about, but it will help understand some of the issues that we’re grappling with communally. Have you ever had an MJE alumni, and my guess would be the answer is yes, who after integrating in the Orthodox community decided to leave?

Mark Wildes: Yes. Feeling not the kind of love and warmth, the “love bomb,” Rabbi Pinny always likes to use that, that we give, and anyone in Kiruv, whether you’re Chabad or Olami does amazing work.

We give a lot of love and attention and we know your name. And when you don’t come a couple weeks in a row, Chani sends you a text and said, “Have you seen so-and-so?” And then you move to a beautiful community like this where, you know, it’s bigger and you’re not paid as attention to. The Davening is not as inspirational. We work like crazy to make our Davening rocking and rolling every Shabbos.

I work like crazy, my Drashas. I’m not saying that a pulpit rabbi in a community like this is not working hard on their Drashas either, but I’m constantly fine-tuning what is going to inspire, what’s going to do this, the food at the Kiddush, who’s talking to who, the whole thing is like, “How do we inspire this Jew so we don’t lose him?” We’re crazy about it. Then you move to a community like this and it’s beautiful, but people are a lot more matter-of-fact about things. You’re raising kids, people are running around, the rabbi’s doing the best that he can to keep his Shul quiet.

You know, we don’t have talking at MJE. The only time there’s talking at MJE is when an Orthodox Jew walks in, stands in the back, and they’ll never sit down, they have to stand in the back and talk. And I’m like I have to explain that it’s a beginner’s service so we don’t speak here as though- anyway, so I think that’s number one. That happens.

They just don’t feel the inspiration, they don’t feel the love. And there’s a money factor. It’s just becoming increasingly expensive, certainly in the Tri-state area. You know, the funniest thing is that whenever we do Shabbatonim in Teaneck, you know, we’re doing the Shabbaton primarily to inspire our students to, you know, check out a beautiful community, but it’s also for fundraising purposes.

So we tend to, you know, stay in some of the nicer areas. Sure. I was walking with a group, it wasn’t here, okay, it was somewhere in the Five Towns. But it’s happened here too.

And somebody stopped me and they were looking, this house was like the size of the block. They’re like, “Rabbi, if I become Orthodox, will I get a house like that?” You know, because that’s kind of what they thought we were presenting.

David Bashevkin: No, but you do get a nursing home immediately. Everyone gets one nursing home after becoming religious.

Mark Wildes: So, you know, there’s a lot of pressure. You have to have both mom and dad working in most situations. And a lot of this is new for people. Sometimes people leave the city, I wish people would stay a little longer, but they find a house, they get out.

I wouldn’t say they’re half-baked, but we weren’t like finished with them yet, you know what I mean, educationally, spiritually. Then they move to the community. We had this one couple, I remember they moved to New Rochelle, lovely couple, and he calls me after they’re there a few weeks and he’s like, “You know, everybody here has children.” And I said, “Dude, I told you to spend a Shabbos there before you went. Of course they all have kids, it’s suburbia.” He just figured he became a ba’al teshuvah and him and his wife, they bought a house in New Rochelle and they didn’t know what to do with themselves.

Everybody’s running after their kids. So those are the factors.

David Bashevkin: So have you found that there is an ideal community that you know is going to take care of your alumni?

Mark Wildes: The smaller, more out-of-town communities our alumni tend to do better in because they’re paid more attention to and they matter more to the community.

The community needs them and I will say something also about the inspirational and I’ll share this, one of my close friends, dear friends who sponsored the book, Omri Dahan and he moved to Oakland, California, him and his wife Jackie, very, very close friends, they sound like I was about to say made aliyah, they moved to Oakland, California. Close enough. And they were like a little like the shul is nice, they love the rabbi, they love the people, but the davening was just like it was not what we would say geshmak.

And he was used to that at MJE and I said, instead of just complaining, I said sit down with the rabbi, he’s got a beautiful voice. And he got three or four guys together and for every single Shabbos they surrounded the bimah, made like a little quasi kind of choir. And instead of just complaining, he tried to improve the situation. So there’s always that, but to answer your question, everybody’s different and some people like having six kosher pizza places in town and three or four schools to choose from.

Some people want that, but not everybody is going to be paid as much attention to. Prices tend to be higher in those neighborhoods and you gotta find a shul that really inspires you.

David Bashevkin: How do you disclose this before it becomes an issue? Meaning you have people who they grow up in this really lovely, almost like cocoon called MJE that has the cultivates a very specific type of Yiddishkeit and at some point people are going to be exposed to the real ugly rodeo called daily living. No but this is, when I used to speak about outreach in NCSY, the analogy that I would bring and quite seriously, of telling them what to avoid was the exact plot, I would tell over the plot of the play, the Book of Mormon.

The Book of Mormon was a play that’s okay whether or not you’re familiar with it, it’s about two Mormon proselytizers who are bozos. They’re not good at what they do and they get sent to Africa and they have to tell this African warlord-beaten community why they should become Mormon. So they ask them, “What’s your issue?” So they said, “We’re getting attacked by this ruthless warlord who’s killing our children and taking our wives hostage” and they’re like, “Become Mormon, that’ll be solved. What else are you dealing with?” They say, “I don’t know, disease, famine.” “Become Mormon, it’ll solve all your problems.” And then they bring them over to Utah, to Salt Lake City and the elders are like, “So why did you come?” They said, “It’s going to cure our disease, it’s going to stop the warlord” and they say, “We don’t do any of that.” How do we avoid because this is an issue, we try to show our best, we want to show our best face and show that Yiddishkeit and Jewish life can be sustained communally in an incredible way and I believe that we do have what to offer to the entirety of the world.

But we also don’t want to be guilty of the bait and switch. We also know that the integration is going to be challenging. There’s a difference between the weekly inspiration and the everyday commitment of raising a Jewish family. How do you make sure that people are going to have the resilience necessary, the commitment necessary, the ability to weather disappointment necessary, that it’s not going to be up up up inspiration for the rest of your life but there’s going to be real challenge and disappointment? How do you ensure that your alumni are ready to weather that?

Mark Wildes: Admittedly, I don’t think we spend a lot of time with any of you preparing you for Teaneck or wherever else you live.

At the same time, we bring them on Shabbatonim because you can talk and talk and talk, but if you spend a Shabbos and a lot of people, Khani organizes our Shabbatonim for many years and people then go back and it’s the nicest thing when you find out that somebody who went to their family that we set them up with got invited a month back for another Shabbos. They start seeing the community, start seeing the realities of the community for themselves. These are adults, they’re smart people, they can figure it out. I think if we overload people with too much of the realities, it’s a Herculean feat for somebody to become a ba’al teshuvah and it’s only getting harder.

And for us to lump on more and more and it’s very hard to articulate how powerfully positive living in a community like this is because at the end of the day, you asked if we have some people who’ve left, yes, but rubba derubba, the overwhelming majority are doing great. Is it perfect? No. Are some people unhappy? Yes. But I don’t have a percentage number, I haven’t done a study.

The overwhelming majority are baruch Hashem happy in their communities, sending their kids to Jewish day schools. But it’s hard, the love bomb that they experienced. at MGE, then there’s life.

David Bashevkin: You know, you mentioned that it’s getting harder to be a baal teshuvah and I think that is true from the perspective of the amount of culture we’ve created in the Orthodox community over the last, I would say 50 years, has become so thick and so strong that there could be things that have nothing to do with Yiddishkeit, but if you don’t know about them you’re not going to be able to survive in the Orthodox community.

But it’s also gotten in some ways a lot easier in the sense that the urgency of what we have and when I say we, I mean specifically the Orthodox community and I’m specifically talking about Shabbos, which I want to ask you about. There is a book that came out this past week that is written by Charlie Kirk who was a Christian that is asking the world to consider Shabbos. It is actually remarkable I find the world’s attention. You have a public figure, non-Jewish, making the case and he’s not the only one.

Professor Jonathan Haidt who is Jewish has been making the case about the importance and significance of keeping Shabbos and he is not shomer Shabbos. He’s just talking about unplugging and getting out and you walk through an Orthodox community exactly as you said, it’s 1992 in the best sense. I mean kids playing in the backyard, it’s genuinely the most compelling experiential yield that I could ever imagine and the only community in the entire world that consistently sustains public Shabbos observance is the Orthodox community, full stop. There is no other community that does it like this.

Maybe, I don’t know if the Amish might have something, but they’re keeping Shabbos the whole week, so it’s different. But we’re really, we’re people, they’re doctors, they’re lawyers, they’re accountants and they get home and there’s real Shabbos. I don’t know what people are doing in the bathroom, I don’t know what, but there’s real, you feel it. I don’t know if people are playing on their phones but at the end of the day in the frum community you feel Shabbos everywhere.

What do you think we would need to do to make the case for Shabbos for the masses? What is holding us back? The end of the day is most Jews don’t really have Shabbos, the Shabbos that we experience. They might make a Kiddush on Friday night, they might go to a class. What do we need to do to really move the needle on Shabbos observance in this country?

Mark Wildes: So Rav Noah Weinberg, of blessed memory, the founder of Aish HaTorah, he had this phrase, awake the sleeping giant. What he meant by awake the sleeping giant, he said the sleeping giant was the Orthodox community and he said that if every Orthodox Jewish family made a concerted effort to engage somebody that is not Sabbath observant, you could make a real difference in the Jewish community and he’s right.

Imagine if all of shomer Shabbos Jews in all of these communities once a month invited somebody to their home, work out the halakhic issues of the transportation and all that, but let’s say we could work that out and there was a systematic program to engage and to inspire the already committed to doing this because there will never be enough kiruv professionals to fix this problem, we will never have it. You need to inspire the laity. And Charlie Kirk, I mean you know what you said before also, it’s true, kiruv is harder than ever, Shabbos is the easiest sell in the world today. It’s much easier for me to sell Shabbos today than it was 20 years ago because of technology.

People are just, it’s compelling. It’s so compelling people are going on their conferences and we’re paying hundreds of dollars to go on these weekends to learn to unplug, right, to have to take their phone and put it in a black box. Oh, it’s brilliant. I mean we’ve been saying this for thousands of years and kudos to Charlie Kirk that he found it for himself.

You know, sometimes we have to have a non-Jew to get the Jews to take our own traditions more seriously. But if we leverage the already committed I think that would be one way of really popularizing Shabbat.

David Bashevkin: One thing that is unique about this room that we have here is that we have MGE alumni who I think their perspective in what it takes and the process of actually integrating into a lived community where Jewish commitment and Yiddishkeit, sustaining Shabbos observance, sustaining Talmud Torah and davening, which I think is really synonymous with the Orthodox community. Not to say that you can’t find lovely Shabbos experiences outside the Orthodox community, but en masse this is what our community does exceptionally well.

I was wondering, and you had mentioned to me before that I could open it up a little bit to some of the people here to pose questions to learn a little bit about the experience of your alumni. So I wanted to ask Jason, from your perspective, when did you realize that MGE was not just about spirituality and enlightenment and all these wonderful things but there was a component about integration within the specific Orthodox community?

Alum: Yeah, it’s a great question and I’ll say I did come to Teaneck on a Shabbaton. I stayed in a home right across the street and fast forward 20 years later I’ve actually We had the benefit of hosting other MJE participants in our home. There is definitely a transition though.

So, we as an MJE community, it is such a unique, loving, supportive community and understanding and integrating into this broader community, I do feel, I think you had the rabbi here potentially look out for us a little bit as we moved, so Rabbi Shalom Baum definitely made a great effort to reach out to us. But I’ll say more broadly, as we settled into our synagogue, which is a very large synagogue, Keter Torah, it was definitely an adjustment to go from this magical Shabbat experience to this much larger room and I used to sit at MJE front row, center and that word passion is so fundamental to…

David Bashevkin: But let me ask one specific question.

Alum: Sure.

David Bashevkin: Was there a moment that you remember that you had like a we’re not in Kansas anymore moment after integrating into the Orthodox community? Like when did you realize I am no longer in this like nice cocoon, but this is a butterfly and they’re flapping their wings pretty aggressively.

Alum: Yeah, I’ll say the biggest thing is when you realize humans are humans, and as you described it in the MJE cocoon, you had this beautiful community of supportive people and you felt like every Orthodox Jew you met was going to be a perfect human being, and I will say…

David Bashevkin: How long did that last?

Alum: I think it might have been the first kiddush club I attended and some of the, so some of that, both the davening certainly being different and some of the indifference and the talking and the distraction, that was definitely a thing. But also, you know, it’s human behaviors, we’re not all perfect and you realize this cocoon that we had at MJE, there are so many beautiful things of the bigger community that you just need to, as you’re going through this step into the bigger community, you need to still keep that fire lit of the positivity because if you don’t keep that fire lit, it’s very easy to get drowned in tuition bills, in the school days are long…

David Bashevkin: So what do you try to remember to not get drowned in the bills? What do you do to preserve that? What do you do to ensure that it doesn’t just become the same Little League and one PTA meeting to the next and then you forget why you’re even here and what you’re sacrificing.

Alum: You know, I’m here with my wife Jackie and just I’ll say we try to within this much larger community create our own community of people that are like-minded, that have passions, that have that feeling and sense. You know, we were last Shabbat at our fellow MJE alumni Sivan’s house and you maintain these connections and you find people even within the broader community who you see they were raised observant and they’re struggling with the fact that the passion is lacking in the community. So you can find those people within, make those relationships and within this bigger ocean of Modern Orthodoxy really do your best to create something that’s fulfilling for you and then I’ll say our kids.

I mean, our kids are sixteen, fourteen, eleven, all going to Frisch High School and Yavne. They’re loving it, their learning has far exceeded what my wife and I do or understand. That’s also part of the Orthodox experience. Yeah, and my wife already tapped out of my son’s Hebrew homework.

He’s done, she’s done. He’s in fourth grade. Yes, yes. So thank goodness, Daniella is our teacher in the home of her younger siblings.

David Bashevkin: I want to do something a little risky. Is there someone else who would feel comfortable talking about some of the struggles and impediments about integration into the community? But also specifically, I’ll be honest, what I really want to try to understand is the component of gender.

I would love to hear from a woman who went through this process and what it is like to integrate. What is your name?

Alum: Meredith Levine.

David Bashevkin: Meredith Levine. And you were raised where?

Alum: In Binghamton.

David Bashevkin: Binghamton University, Vestal. Oh sure, sure, it’s pretty close to the Berkshires actually, like an hour and change away in upper Albany. Cold, very cold. Tell me about your experience of going from kind of outside and MJE now brings you and funnels you to, are you now living within an Orthodox community?

Alum: So I live in Teaneck.

It was a cocoon experience. Being part of MJE. It was awesome.

And then we get married and we moved when our oldest was four years old to Teaneck, and it was to connect so quickly to people, not so easy, you know, the bills, not so easy. And one big shock was there’s all personalities in public school, but in Modern Orthodox day school, it’s they can’t deal with certain personalities.

David Bashevkin: Four types of personalities.

Alum: Yeah, they have it’s very narrow.

Yes. And then you’re stuck with this feeling of, do I belong? Do we belong? Should we leave? How can we make this work? But I do think that Hashem is with you. I honestly feel…

David Bashevkin: When you have those moments of doubt, what keeps you? Why do you say I am exactly where I’m supposed to be?

Alum: Actually, Rabbi Wildes was part of our uh-oh, we don’t belong, what should we do? And he’s, how old is he? Have him go for a year or two, pre-K, kindergarten, whatever, and then in first grade, he doesn’t have to go before first grade.

Let’s see what happens. And just yesterday, he was practicing laining and his grandfather heard him echo the sound and it was amazing. It was so beautiful.

David Bashevkin: That this child who you were considering do we want to really walk down this path is now studying for his Bar Mitzvah.

Alum: Well no, he wants to keep going. He did his Bar Mitzvah, he’s thirteen years old, he wants to hold on to this talent, he feels that this is a good skill set and he wants to continue it, and people come up to me and they say, you know, he was the chazzan and he was doing so great. He’s that guy that last year in eighth grade, this other kid took up all the spots to…

David Bashevkin: This is tough for me to hear because my parents’ greatest disappointment is that I did not become a Ba’al Korei.

They genuinely still look at me with great disappointment.

Alum: We get nachas notes from his from the school.

David Bashevkin: I want to ask about something specific, which is the world of tzniut, which is modesty, which is how you integrate within the community, there are norms of how people dress. Did you find the integration into the gendered expectations within the Orthodox world were difficult at anything take you, what on earth is this about? How did that component of the integration work for you?

Alum: First of all, there’s a variety even within Modern Orthodox community.

There are schools that are more machmir, there are shuls that are more machmir, there are personalities that are one way or the other and then the feeling for me is the comfort is knowing that we’re all like a rainbow and…

David Bashevkin: Machmir meaning stringent, I love it, I had to translate for 18Forty, sure.

Alum: But that’s how I see it. I don’t see it as being like everything is black and white and I do take it back to Hashem, which is how I got started with just becoming more religious to begin with.

Why would I become more religious? I see the miracles. Every step that I take that is closer to feeling connected to Hashem is a step that I see, I see the results of it and it’s amazing. I wouldn’t want to give that up.

David Bashevkin: I must say also, genuinely moving.

Just something that Meredith, you’re off the mic, it’s okay, that was fantastic.

Mark Wildes: Just something that Meredith, you notice how many times Meredith mentioned Hashem‘s name in her response. And you weren’t asking about Hashem, but that I think also is something that gets a little more emphasized in the kiruv bubble, because you got to turn people on to a relationship with Hashem and I think that’s also been a little of a challenge for people once you get into the Orthodox community, there’s a lot of Torah, but it doesn’t always focus on your personal relationship and feelings for Hashem. We’re a little more reticent in the Modern Orthodox world to talk about that, I find.

And I’d love to see a little more of a shift and I think one way of doing that, I mean, you know, everyone’s got different hashkafos on Hashem, you know, we just had Rabbi Benjamin Blech speak, today he’s 92 bli ayin hara and he was incredibly powerful and he wrote a book about tzaddik ve’ra lo, why bad things happen to good people. And he spoke for 30 minutes about our relationship with Hashem and going through tough times and how that reflects on our feelings when we’re angry with God, we’re not. I just think if we had more of that kind of conversation, I think the Orthodox community would also be a little more of an attractive place, a destination place for less affiliated Jews, because people are interested in talking about this.

David Bashevkin: I could not agree more and really for the work that you are doing, especially in this moment, post-October 7th, so many people are waking up and what they’re looking for is a vision of Yiddishkeit that could even in potential address the entirety of the Jewish people.

And what I think is so amazing about your work and the community of MJE is that it truly is an articulated vision of this is a Yiddishkeit that you can hold on to, you can keep, and it is going to be able to integrate for the rest of your life of a lifelong Jewish commitment. And I always end my interviews with more rapid-fire questions. We have your book over here, which is absolutely outstanding, called The Jewish Experience: Discovering the Soul of Jewish Thought and Practice, which is such an important book because I know this deeply, we don’t have as many books as you would think to offer somebody to say, read this to learn more about Yiddishkeit, to learn more about Jewish practice and Jewish life. Obviously aside from your own book, what are your go-to books when someone is asking you to to learn more about Jewish life.

Mark Wildes: Rabbi Soloveitchik, The Lonely Man of Faith, if they’re more existentially, intellectually oriented; Aryeh Kaplan, almost anything he wrote if they’re very into mysticism and Kabbalah then I’ll give them those stuff but the more NCSY ones are amazing.

David Bashevkin: We republished those.

Mark Wildes: Yeah, they’re excellent.

I would say I’m still going with Herman Wouk. I quoted from him just last night. This is my God. And Donin’s To Be a Jew.

I’ve been using those for years and the reason I wrote this was to give a little more of a modern, if you will, updated version of Donin’s To Be a Jew, Herman Wouk. And it’s really excellent. It covers a whole lot and you pack in a ton there and it’s very accessible, very… I genuinely read it and it was really, really great.

David Bashevkin: My next question, I’m always curious, if somebody gave you a great deal of money and allowed you to take a sabbatical with no responsibilities whatsoever to go back to school and get a PhD, what do you think the subject and title of your dissertation would be? What would you want to study?

Mark Wildes: Dissertation on philosophy specifically, I’d love to get a little deeper into what the Rav wrote his dissertation on Hermann Cohen’s approach to epistemology, how we know things.

David Bashevkin: Oh wow, that is quite fascinating. I did not think you would go there. Look at that.

Kiruv, not academic. Very fancy. Okay, you show them. Before my last question, I’m going to throw in another one because I’m very curious about people’s sleep patterns, but I’m going to be perfectly honest with you, I’m more curious about your hair maintenance.

Maybe we can do that off camera. It really is, I want you to know, your hair is a Kiddush Hashem. It really is. It inspires me.

I would become frum if I knew, forget taking them to Windsor, just show them these guys, these luscious locks of hair. I would become more religious right here right now. But I am curious about people’s sleep schedules. What time do you go to sleep at night and what time do you wake up in the morning?

Mark Wildes: I sleep on one side so it looks great in the morning.

I’m a late night, I’m really good at night. I’m up at night, so I’m not saying this is terribly healthy, I go to sleep between one and two.

David Bashevkin: And you wake up?

Mark Wildes: I wake up, I hit the 8:00 minyan at the Jewish Center. Nothing to be embarrassed there, very impressive.

David Bashevkin: Rabbi Mark Wildes, this was an incredible privilege and pleasure.

Mark Wildes: Thank you all so much for joining us tonight. Want to thank Rabbi Bashevkin.

David Bashevkin: Okay, thank you all friends, thank you, thank you so much, that was lovely.

Five years ago, a friend of 18Forty, someone who wrote an incredible series of articles about theology and Jewish faith named Steven Gotlib, he wrote an article for the Lehrhaus called Is Modern Orthodox Kiruv Possible? And it is a powerful article where he kind of explains why he himself decided to pursue a pulpit where deliberately he has a congregation where not everyone affiliates as Orthodox and he looks at it as kind of this contemporary form of kiruv. He is an Orthodox rabbi ordained from Yeshiva University and he’s trying to re-articulate this kind of message by going out to a less, not a classic bastion of Orthodox community and instead deliberately serves in a community because if you listen to our episode with Steven Gotlib, which is fantastic, he himself went through the Reform community, the Conservative community, the Orthodox community and kind of landed here and feels both the strength and the joy and the inspiration that is able to be sustained within the Orthodox world but also is realistic, understands what the lives and commitments and worldview of those who live outside the Orthodox community are grappling with and struggling with and trying to bridge these two together is what led him to kind of write this article, which is really interesting, called Is Modern Orthodox Kiruv Possible? And in that article, he grapples with a lot of the things that we discussed. One thing that he cites Elliot Cosgrove, he’s a Conservative rabbi in Park Avenue Synagogue who has written some really fascinating stuff about both the struggles of the Conservative movement and the relative successes of the Orthodox world and he writes specifically about Chabad. This is Steven Gotlib quoting Elliot Cosgrove: come as you are, do whatever you want to do in our private sphere, when you walk into a Chabad house, we promise you it will be brimming with authenticity.

Chabad knows that this world is full of people who want to make their choices in the private sphere but when they do access religious living, they want it to be Torah true. Chabad dresses the part, they claim to be the real deal and they make no judgments about who you are and where you came from. And you know what, surprise, surprise, they are the fastest-growing segment of American Jewish life. That is a beautiful articulation of the outlook of Chabad and when he is thinking about it within the Modern Orthodox world, I actually disagree with Steven’s next part of his argument where he essentially says one of the reasons of why we are struggling is because the Modern Orthodox world has not defined itself to itself.

I do not think that is at all a part of the problem. I don’t think that we need a better definition of our ideology. I don’t think healthy Jews wake up in the morning and think about the ideology of the movement that they belong to. I think that there’s something much more organic and real and that there’s an alignment of this is how I want to live my life.

No one is living the brochure of any movement, ideology, hashkafa. We all have lives that require negotiation. We’re all striving. We all know that we can do better.

We have good days. We have bad days. I don’t think the problem is a different definition of Orthodoxy. I actually think that the answer to this question is Modern Orthodox kiruv possible, and I would answer with a resounding yes.

But I think that there are different forms of kiruv and each are championed by a different segment of our community. There is the kiruv so to speak of Chabad. They may not call it kiruv, but the world of Chabad, which is exactly as Elliot Cosgrove described it, which is essentially providing an authentic Jewish experience to whoever is seeking it, whether it’s mere need of matzos or a kosher meal or a sweet dvar Torah or a farbrengen, a group of people, whatever it is, we will provide to you an authentic Jewish experience. Come in and it’s beautiful and it’s amazing.

It is this real mentality of no Jew left behind. Everyone deserves some semblance of community and Chabad has kind of created this network where they’re this community to the world. They’re the Jewish community, they’re the Chabad house next door, but it’s throughout the world. It is something incredible and their mechanism, which I think they do incredibly well, are these Chabad houses, preschools, I think they really do an outstanding job.

I think there is the kiruv style of NCSY, which leans heavily on summer programs, on Shabbatonim, which are unique to teenagers who are able to go away on a Shabbaton, a weekend experience, they’re able to go away for the summer. That is a different almost form of kiruv. It doesn’t mean that other people can’t also run summer programs and have Shabbatons, but there’s kind of a unique approach to how is kiruv done within NCSY. And then there is a kiruv of the yeshiva world, which I think is about opening up the treasures of Torah and having in-depth Torah classes, introducing people to Talmud study, introducing people to in-depth Jewish thought, machshava.

And I think that is also really, really incredible. I think there is kiruv of the chasidic world. It’s almost like an inverse kiruv. They’re not necessarily, though there are some who do, who are going out and trying to connect to your random Jews in the middle of nowhere, but at the very least every American Jew is indebted to the chasidic world for number one kind of modeling the intensity of commitment that we even have an image of what that form of Jewish life can look like.

I always think of that dialogue in A Few Good Men: ‘You need us on that wall, you want us on that wall.’ And I think that’s very true of the chasidic community. They’re making our Sifrei Torah, so many in the chasidic world are the ones who are getting us kosher meat, who become shochtim, etc., etc. But even beyond that, I think the chesed, the kindness that is done in the chasidic world, even for people beyond, whether it’s bikur cholim and people who are struggling with a family member themselves in the hospital, whether it’s end of life, of making sure everybody can sit and mourn properly, the work that they’ve done for shiva, I think they’ve done incredible works in chesed and I really look throughout the Jewish world and I try to always see that positivity. And even when you’re 100 percent aware of the negativity that exists in every single community, community by nature is going to have some negativity in it, it’s not tailor-made, that’s called an individual. Communities have a lot of people.

But I also think that there is a unique form of kiruv of the Modern Orthodox world. It’s not NCSY, which is for teens. It is not Chabad houses. It’s not maybe the source sheets or the Torah that’s affiliated with yeshiva outreach, and it’s not the outreach affiliated with the chasidic world, though I think all Jews instinctively are crying out and looking to connect to one another.

Where I think the Modern Orthodox kiruv is actually non-professional kiruv, non-professional outreach. I want to kind of lob off that term. I don’t know that the Modern Orthodox community ever will or even should be the leaders in professional kiruv. I think where the Modern Orthodox community can actually shine deeply and provide a model for is what does non-professional kiruv look like? What does non-professional Jewish outreach look like? What does it mean to be a committed religious Jew in the workplace? What does it mean to have friendships and connections? You’re on a Sunday baseball team, you’re in an ice hockey league, whatever it is, where you have people of different religious backgrounds and somebody who can present organically the joy of their life.

And you don’t have to be fake about it. The joy of their life with all of the normalcy of life, with all the frustration. rations of life, with all of the difficulties of life, but somebody who in this world in 2026 is choosing, because we’re all choosing, no one’s forced to be religious in adulthood anymore. Not in the United States of America.

You call the cops. But choosing and saying, I choose to build my life here, and I want to share why. And just being a shining example, I think is actually the ultimate and most storied form of outreach that we have ever had. It’s the outreach that organically happens when two Jews connect and have a friendship and meet one another.

They learn about each other’s lives and commitments. And the same way that two people can meet each other and could tell somebody about a new workout regimen, a new gym membership, or things that have contributed to their lives, we in the Modern Orthodox community—I’m sorry I keep using the word we, not all of our listeners are Modern Orthodox or Orthodox, I’m just including myself in there and just speaking organically—but I think that vision of Jewish outreach where kind of every Jew in their everyday lives really looks at themselves as a representative of something, of something amazing, of something almost unimaginable, a remnant of the past and kind of a taste of what the future could look like. Someone who has the authenticity and confidence of their religious home is the ultimate form of kiruv to go out in the world and look at every interaction you have with another person, not as a, oh did I get them frum yet, did I make them Orthodox, did I do it, not looking at other Jews like an inanimate object for your mitzvah, but forming those deep connections because ultimately religious growth begins with understanding one another’s lives. It’s not just going to drop down.

You have to understand what’s going on in people’s lives. And that kind of non-professional kiruv of peering into somebody else’s life—I know the work pressures, I know the life pressures, I know all of this—and I think that there is a model of sustained communal engagement that could radically elevate your home life, your family life, the relationship with your spouse and with your children, and find that community. But having those conversations, I think, is the most organic and holiest form of outreach. And anybody who’s wondering, well, that’s not at all what Judaism represents to me, I would never say that to somebody, I hate it, it’s painful, it’s difficult, it’s too expensive—whatever difficulties that people within the Orthodox world very much have, but if that is so intense in your own life, that is a good wake-up call to kind of reexamine your own religious life.